Police Reform and the Dismantling of Legal Estrangement

abstract . In police reform circles, many scholars and policymakers diagnose the frayed relationship between police forces and the communities they serve as a problem of illegitimacy, or the idea that people lack confidence in the police and thus are unlikely to comply or cooperate with them. The core proposal emanating from this illegitimacy diagnosis is procedural justice, a concept that emphasizes police officers’ obligation to treat people with dignity and respect, behave in a neutral, nonbiased way, exhibit an intention to help, and give them voice to express themselves and their needs, largely in the context of police stops. This Essay argues that legitimacy theory offers an incomplete diagnosis of the policing crisis, and thus de-emphasizes deeper structural, group-centered approaches to the problem of policing. The existing police regulatory regime encourages large swaths of American society to see themselves as existing within the law’s aegis but outside its protection. This Essay critiques the reliance of police decision makers on a simplified version of legitimacy and procedural justice theory. It aims to expand the predominant understanding of police mistrust among African Americans and the poor, proposing that legal estrangement offers a better lens through which scholars and policymakers can understand and respond to the current problems of policing. Legal estrangement is a theory of detachment and eventual alienation from the law’s enforcers, and it reflects the intuition among many people in poor communities of color that the law operates to exclude them from society. Building on the concepts of legal cynicism and anomie in sociology, the concept of legal estrangement provides a way of understanding the deep concerns that motivate today’s police reform movement and points toward structural approaches to reforming policing.

author. Climenko Fellow & Lecturer on Law, Harvard Law School; Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology & Social Policy, Harvard University. I am deeply indebted to the Johns Hopkins Poverty & Inequality Research Lab, particularly the PIs and fellow co-PI of the Hearing Their Voices (HTV) Study—Stefanie DeLuca, Kathryn Edin, and Philip Garboden. I gratefully acknowledge funding from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Grant GA-2015-X3039, and the Johns Hopkins 21st Century Cities Initiative. I am grateful to the members of the HTV research team: Janice Bonsu, Steven Clapp, Meshay Clark, Kaitlin Edin-Nelson, Mitchell Generette, Marika Miles, Daveona Ransome, Larry Robinson, Trinard Sharpe, Geena St. Andrew, and Juliana Wittman. Many thanks also to two inspiring Baltimore organizations, Thread and the Youth Empowered Society (YES) Drop-In Center; special thanks to Sarah Hemminger and Frank Molina of Thread and Ciera Dunlap, Michael Jefferson, Sonia Kumar, and Lara Law of YES. For generous feedback and helpful suggestions, I thank Amna Akbar, Regina Austin, Ralph Richard Banks, Dorothy Brown, Jonathan Bruno, Devon Carbado, Guy-Uriel Charles, Matthew Clair, Beth Colgan, Sharon Dolovitch, Yaseen Eldik, Erik Encarnacion, Malcolm Feeley, Barry Friedman, Lisa Kern Griffin, Laurence Helfer, William Hubbard, Aziz Huq, Jeremy Kessler, Issa Kohler-Hausmann, Máximo Langer, Adriaan Lanni, Tracey Meares, Justin McCrary, Kimani Paul-Emile, Alicia Plerhoples, Megan Quattlebaum, Jed Shugerman, David Alan Sklansky, Seth Stoughton, Allison Tait, Shirin Sinnar, Tom Tyler, and Alexander Wang. I also thank Asad Asad, Amy Chua, Matthew Desmond, Michèle Lamont, Maggie McKinley, Judith Resnik, Robert Sampson, Stacey Singleton-Hagood, Jeannie Suk Gersen, and Bruce Western for consistent support and insight. This work benefitted from discussions at Boston College, Boston University, Brooklyn Law School, Columbia, Cornell, Duke, Fordham, Georgetown, New York University, Northeastern, Seton Hall, Stanford, University of California-Berkeley, University of California-Los Angeles, University of Chicago, University of Connecticut, University of Georgia, University of Pennsylvania, University of Richmond, University of South Carolina, University of Texas, William & Mary, and Yale University, and with participants in Yale Law School’s Moot Camp and The Yale Law Journal Reading Group. I am especially grateful for generative commentary and support from participants in the Duke University School of Law Emerging Scholars Workshop & Culp Colloquium, and for the editorial expertise of the staff of The Yale Law Journal , especially Peter Posada and Sarah Weiner. Most of all, I am grateful to the young Baltimoreans who shared their stories with us, whose lives are the reason that getting police reform right is so important.

Introduction

In the concluding paragraphs of her fiery dissent in Utah v. Strieff , 1 Justice Sotomayor invoked W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, Michelle Alexander, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Marie Gottschalk in concluding that the Court’s decision, which further weakened the power of the exclusionary rule to deter unconstitutional police conduct, 2 sent a message—particularly to people of color—“that you are not a citizen of a democracy but the subject of a carceral state, just waiting to be cataloged.” 3 Justice Sotomayor laments “treating members of our communities as second-class citizens.” 4 Yet despite the boldness of her statements, in some ways Justice Sotomayor might not have gone quite far enough in articulating the troubling implications of our Fourth Amendment jurisprudence.

Justice Sotomayor’s analysis understates the problem on two fronts. First, in addition to the jurisprudential message that poor people of color are “subject[s] of a carceral state” or “second-class citizens,” research in sociology, criminology, political science, and other fields suggests that these groups often see themselves as essentially stateless—unprotected by the law and its enforcers and marginal to the project of making American society. Even as criminal procedure jurisprudence sets the parameters of what police may do under the law, it simultaneously leaves large swaths of American society to see themselves as anomic, subject only to the brute force of the state while excluded from its protection. The message conveyed in policing jurisprudence is not only one of oppression, but also one of profound estrangement.

A second understatement relates to the understanding of whose safety is at risk when the Fourth Amendment insufficiently checks the power of the police. Justice Sotomayor uses the second-person pronoun “you” to convey to a public audience both the universality and the personal proximity of the risk of police control. 5 Yet this literary technique, though effective, obscures the reality that the sense of alienation in a carceral regime emanates not only from what police might do to “you,” but from what they might do to your friends, your intimate partners, your parents, your children; to people of your race or social class; and to people who live in the neighborhood or the city where you live. In other words, estrangement from the American citizenry is not merely an individual feeling to which people of color tend to succumb more readily than white Americans do; rather, estrangement is a collective institutional venture.

The Black Lives Matter era has catalyzed meaningful discussion about the tense relationship between the police and many racially and economically isolated communities, and about how policing can be reformed to avoid deaths like those of Rekia Boyd, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and more. However, contemporary discourse has often neglected or obscured deeper discussion about the relationship between African Americans—especially poor African Americans—and the police. What is the nature of these relationships? How can scholars and policymakers more roundly understand their contours and potential strategies for change?

Many scholars and policymakers have settled on a “legitimacy deficit” as the core diagnosis of the frayed relationship between police forces and the communities they serve. The problem, this argument goes, is that people of color and residents of high-poverty communities do not trust the police or believe that they treat them fairly, and that therefore these individuals are less likely to obey officers’ commands or assist with investigations. 6 This argument took its most prominent position in the May 2015 Final Report of the White House Task Force on 21st Century Policing . The Report sets forth the goal of building trust and legitimacy as both the first pillar of its proposed approach to police reform and as “the foundational principle underlying [the Task Force’s] inquiry into the nature of relations between law enforcement and the communities they serve.” 7 “Trust” is a broad term, but the Report and much of the policymaking energy surrounding shifts in police governance adopt an understanding of trust that treats it as virtually synonymous with legitimacy. 8

Ample empirical evidence supports the idea that African Americans, and residents of predominantly African American neighborhoods, are more likely than whites to view the police as illegitimate and untrustworthy, along several axes. 9 Empirical evidence suggests that feelings of distrust manifest themselves in a reduced likelihood among African Americans to accept law enforcement officers’ directives and cooperate with their crime-fighting efforts. 10 According to much of this line of scholarship, the primary tool to achieve greater obedience to the law and law enforcement, regardless of race, is procedural justice: police officers treating people with dignity and respect, behaving in a neutral, nonbiased way, exhibiting an intention to help, and giving people voice to express themselves and their needs in interactions. 11

Yet many reformers would likely disagree that obedience to law enforcement is the central concern in America’s current conversation on police reform. Indeed, in many of the cases that have most catalyzed the Black Lives Matter movement, the victims of police violence were not disobeying the law, 12 were complying with officers’ demands, 13 or were suspected of violating petty laws that are likely unworthy of strong enforcement efforts or penalties. 14 A large body of scholarship on criminal justice attempts to denaturalize the assumed link between obeying the law and criminal justice contact. 15 Scholars have shown that recent trends in criminal justice such as pervasive stop-and-frisk, increased misdemeanor prosecution, and mass incarceration are not primarily consequences of increases in criminal offending. Instead, these scholars suggest that the American criminal justice system has dual purposes, only one of which is crime response and reduction. Its other, more insidious function is the management and control of disfavored groups such as African Americans, Latin Americans, the poor, certain immigrant groups, and groups who exist at the intersection of those identities. 16 From a social control perspective, increasing compliance and cooperation with law enforcement may well be valuable aims, but they should not be at the root of police reform efforts. Deploying legitimacy theory and procedural justice as a diagnosis and solution to the current policing crisis might even imply, at some level, that the problem of policing is better understood as a result of African American criminality than as a badge and incident of race- and class-based subjugation.

Reformers’ emphasis on police legitimacy has caused them to focus heavily on training of frontline officers to behave in a procedurally just manner during stops, with a goal of promoting legitimacy. The White House report, for example, names training and education of frontline officers as Pillar Five of a six-pillar approach, and training is mentioned as an “action item” under all of the five other pillars. 17 Numerous news reports, professional reports, and articles in professional magazines tout procedural justice as the key intervention that will resolve the problems that have catalyzed Black Lives Matter. 18 Police departments across the country, in wide-ranging cities such as Chicago, Illinois; Stockton, California; and Birmingham, Alabama, have implemented procedural justice training. 19 The Obama Justice Department’s consent decrees with troubled departments, such as Cleveland and Ferguson, mandate departments to adopt and implement procedural justice principles and training. 20 As the theory is at times presented, particularly among police officers, responding to the concerns of marginalized communities is as simple as following “the Golden Rule.” 21

While momentum for procedural justice training seems persistent on a local level, 22 the Trump Administration seems unlikely to embrace and advocate for this sort of reform. Trump has consistently indicated that he is generally supportive of police officers, but he has not fully articulated what support means at a concrete level. While Candidate Trump espoused the sanctity of state and local control over policing, 23 President Trump took to Twitter to threaten to send “the Feds” to Chicago to respond to shootings, which generally fall within the jurisdiction of local police departments. 24 Candidate Trump endorsed aggressive, ineffective “stop-and-frisk” policies 25 —meaning policies that target predominantly black and brown neighborhoods in the style declared unconstitutional in New York City, 26 not the stops-and-frisks based on individualized reasonable suspicion authorized in Terry v. Ohio . 27 Meanwhile, President Trump floated a preliminary federal budget, drafted by the Cato Institute, that indicated the administration would seek to eliminate funding for the Justice Department’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS). 28 The COPS Office distributes federal funding to local departments to hire more police officers, which enables departments to hire enough officers to carry out intensive approaches like stop-and-frisk. 29 Without COPS funding, local departments may lack the staffing to fulfill Trump’s alleged goal of ratcheting up stop-and-frisk measures.

Recent executive orders on criminal justice, issued just one day after the Senate confirmed Trump’s Attorney General Jeff Sessions, continue in the ambiguous vein of supporting the police while gently alluding to ways that impulse might conflict with responding to the concerns that yielded Black Lives Matter. One executive order, for example, creates a “Task Force on Crime Reduction and Public Safety” that supports “law and order” and authorizes the task force to “propose new legislation that could be enacted to improve public safety and reduce crime”—language that sounds supportive of increased criminalization and expansion of the carceral state. 30 Another, which purports to prevent violence against police officers, similarly proposes “new Federal crimes, and increase[d] penalties for existing Federal crimes” against officers. 31 In the context of recent debates over police legitimacy and police-community relations, these orders implicitly paint the challenges facing criminal justice as stemming solely from criminality. They ignore the institutional failures of certain police departments and erase the structural underpinnings of tense police-community relations, specifically racial isolation and class marginalization.

The appointment of Jeff Sessions as United States Attorney General suggests that the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division will end its investigations of local departments, 32 as it did under Attorneys General Alberto Gonzales and Michael Mukasey during the second George W. Bush Administration. 33 It is also likely that the DOJ’s funding support for the National Initiative for Building Community Trust & Justice, founded on legitimacy and procedural justice principles, will end. 34 Yet given the wide embrace of procedural justice on a local level and through national policing organizations, it would not be surprising if procedural justice remained the prevailing approach even if the federal government steps back from actively pushing it. 35

Choosing a theory of the policing crisis and its solutions is critical for advancing meaningful, effective reform. In the world of police governance and practice, perhaps more than in other spheres, theory matters for determining what police departments and officers do on the ground. Much of the impetus for broken-windows policing, 36 community policing, 37 “hot spots” (or focused deterrence) 38 and other predictive policing, 39 and now procedural justice and legitimacy came from or ripened in the academy. Through a panoply of large and small policy decisions, theory trickles into the daily work of frontline police officers. Thus, getting the theory right by accurately diagnosing the policing crisis is central to the practical project of reforming policing.

This Essay broadens the usual lens by proposing legal estrangement as a corrective to the prevailing legitimacy perspective on police reform. Like Justice Sotomayor in Strieff , 40 the legal scholars who are setting the police reform agenda have not fully captured the nature of the distrustful relationship between the police and poor and African American communities. The theory of legal estrangement provides a rounder, more contextualized understanding of this relationship that examines the more general disappointment and disillusionment felt by many African Americans and residents of high-poverty urban communities with respect to law enforcement.

Nearly twenty years ago, sociologists Robert J. Sampson and Dawn Jeglum Bartusch described “‘anomie’ about law” in predominantly black and poor neighborhoods in Chicago, a phenomenon they labeled “legal cynicism.” 41 By “anomie,” Sampson and Bartusch were describing ruptures in the social bonds that connect individuals to their community and, in particular, to the state through law enforcement. Building from their work and from other sociology and criminology scholarship on legal cynicism, 42 I introduce the concept of legal estrangement to capture both legal cynicism—the subjective “cultural orientation” among groups “in which the law and the agents of its enforcement, such as the police and courts, are viewed as illegitimate, unresponsive, and ill equipped to ensure public safety” 43 —and the objective structural conditions (including officer behaviors and the substantive criminal law) that give birth to this subjective orientation.

The concept of legal estrangement has the power to reorient police reform efforts because it clarifies the real problem of policing: at both an interactional and structural level, current regimes can operate to effectively banish whole communities from the body politic. The legal estrangement perspective treats social inclusion as the ultimate end of law enforcement. This view extends and reformulates the legitimacy perspective, which tends to present inclusion primarily as a pathway toward deference to legal authorities. 44 The legal estrangement approach encourages a fuller, theoretically informed set of interventions into police governance.

Part I locates distrust of the police among many African Americans and in many disadvantaged neighborhoods as a particular, poorly understood problem. To illustrate the analytical advantages of legal estrangement over legitimacy theory, Part II tells the story of Shawna, a young African American woman living in Baltimore, Maryland. Part III explains how legitimacy theory and legal estrangement theory take different approaches to understanding the current policing crisis. It demonstrates the power of legal estrangement theory to improve legitimacy theory and its concomitant procedural justice approach, which has had great influence over the police reform agenda. 45 Part IV erects a tripartite theory of legal estrangement. It posits that three types of socio-legal processes contribute to legal estrangement: procedural injustice, vicarious marginalization, and structural exclusion. In addition, Part IV illustrates the lived experience of these phenomena using portraits from rich narrative data collected from youth in Baltimore, Maryland in the wake of the death of Freddie Gray. Part V moves from the critical and theoretical to the prescriptive. It argues that, in order to dismantle (or at least to reduce) legal estrangement, multiple levels of government must engage in policy reform aimed not only at procedural injustice, but also at vicarious marginalization and structural exclusion. These reforms have a greater likelihood of producing social inclusion, the deepest purpose of the policing regime.

I. the blight of police distrust in african american communities

For as long as scholars have studied the relationship between African Americans and criminal justice, they have documented deep distrust of the system. In the early twentieth century, W.E.B. Du Bois was likely the first scholar to empirically document this distrust. 46 As part of a series of studies of African American life, Du Bois and his collaborators collected survey, interview, and administrative data on crime, arrest, and incarceration . 47 They found, among other things, that white officials and black men had greatly divergent perspectives on the possibilities of justice for African Americans in Georgia courts. 48 Du Bois reasoned that punishment practices prevalent at the time, such as lynching, “spread[] among black folk the firmly fixed idea that few accused Negroes are really guilty.” 49 He also condemned the relative lack of legal protection for African Americans, as well as criminal justice practices such as the leasing of convicts, that sent a message to African Americans that the purpose of the system was to make money for the state rather than to rehabilitate supposed lawbreakers. 50

Du Bois’s research was prescient, at least with respect to the direction of research and scholarship on African Americans’ relationship to the crime control system over the next century. A high watermark was the 1968 Kerner Commission Report, commissioned by the Johnson Administration in the wake of twenty-three episodes of urban unrest during the mid- and late 1960s. 51 The Report concluded that, for many African Americans, the “police have come to symbolize white power, white racism, and white repression.” 52 Like Du Bois’s Georgia study, the Report documented “tension” and “hostility” between law enforcement and urban African Americans, blaming the “abrasive relationship” on a combination of increased demands for protection and service and the police practices thought necessary to provide those services. 53 In the South and in the Northeastern and Midwestern Rust Belt cities where many African Americans relocated during the Second Great Migration, police forces often functioned to maintain the expulsion of African Americans from the center of social and political life, at times violating the law in service of racial control. 54 Despite pervasive harsh policing that ostensibly was intended to suppress and deter crime, African Americans felt inadequately protected. 55

The litany of evidence confirming the existence of a tense and distrustful relationship between African Americans and law enforcement mounted steadily over the ensuing decades. John Hagan and Celesta Albonetti, for example, used data from a national survey conducted in the late 1970s to conclude that, although African Americans were more likely than whites to see all aspects of the criminal justice system as unjust, they perceived the police as the most unjust aspect of the criminal justice system. 56 Drawing from nationally representative survey data from the late 1980s, Tracey Meares argued that many African Americans experience “dual frustration” with drugs on the one hand and with harsh courts and law enforcement on the other. 57 More recently, Lawrence Bobo and Victor Thompson reached similar conclusions, finding that while sixty-eight percent of white respondents expressed at least “‘some’ or ‘a lot’ of confidence in the police,” only eighteen percent of black respondents would say the same. 58 Contemporary events, particularly the increased political, social, and academic attention directed at police use of force because of the Black Lives Matter movement, have shed new light on longstanding tensions between African Americans and law enforcement. 59 Newer research embeds the problem of police distrust within a larger framework of race- and class-based marginalization, examining a range of police practices and neighborhood conditions. 60

Much of this research documents African American distrust or dissatisfaction with the law and law enforcement without clearly articulating the meaning of distrust or the precise content of dissatisfaction. This omission could exist, in part, because the sources of distrust and dissatisfaction are seen as relatively obvious. A large body of historical research has documented the entanglement of police in the long-running national project of racial control. 61 Yet our failure to be specific about the meaning, origins, and content of distrust has produced a worrisome incompleteness in the diagnosis of the problem, and thus in the prognosis and program of treatment. 62

Trust is a multidimensional, difficult-to-define concept that scholars operationalize using myriad approaches. 63 Yet in the world of policing scholarship, the leading scholar and definer of trust is Tom Tyler. Rather than understanding trust and legitimacy as synonymous, Tyler conceptualizes trust as part of the larger umbrella of legitimacy. Theoretically, Tyler defines legitimacy as a person’s “perceived obligation to obey” the law, 64 or “the belief that legal authorities are entitled to be obeyed and that the individual ought to defer to their judgments.” 65 Different surveys and experiments define legitimacy in distinctive ways, but the core formulation considers people’s sense of obligation to follow the law; their sense of whether the law “operates to protect the advantaged” (which Tyler and Huo call “cynicism about the law”); 66 their trust in legal institutions, specifically police officers and judges; and their favorability toward the police and the courts in their city. 67 The conceptual distinctions between all of the manifestations of trust that appear in the large body of legitimacy scholarship can become blurry, and it is beyond the scope of this Essay to reconcile all of these iterations. The core insight to keep in mind is that, in the version of legitimacy theory that policing policymakers have adopted most completely, trust between police and communities is understood as a problem of illegitimacy: the key concern is the degree to which people will choose to obey the law and its enforcers.

Much literature has shown that, regardless of how trust is measured or conceived, African Americans, particularly those who are poor or who live in high-poverty or predominantly African American communities, tend to have less trust not only in police, but also in other governmental institutions, in their neighbors, and even in their intimate partner relationships in comparison to other racial and ethnic groups in the United States. 68 The picture that emerges from the full body of research on race and trust is one of profound marginalization, a social diminishment that—while not encapsulating the fullness of the African American experience—indicates that poor African Americans as a whole tend to have a social experience distinctive from those of other ethnic and class groups in the United States. Structural disadvantage yields a broader cultural structure of mistrust. Most discussions of African American distrust of the police only skirt the edges of a deeper well of estrangement between poor communities of color and the law—and, in turn, society.

ii. two diagnoses

A. a crisis of legitimacy.

The most widely accepted diagnosis of the cleavage between the police and African Americans (particularly poor African Americans) centers on legitimacy . Scholars argue that African Americans are less likely than other groups to see the police as legitimate authorities, meaning that as a group they are less likely to have “a feeling of obligation to obey the law and to defer to the decisions made by legal authorities.” 69 Although trust and legitimacy are distinct concepts, scholars and policymakers tend to treat the ideas as functionally equivalent for reform purposes. The core determinant of whether law enforcement is perceived as legitimate, and thus worthy of obedience and assistance, is whether police officers behave in a procedurally just manner. 70 Procedural justice is believed to encapsulate several components, including treating people with dignity and respect, voice (which can include citizen participation and allowing individuals to express their concerns), neutrality (freedom from bias), and conveying trustworthy motives (explaining how the police are helping reach an important social goal). 71 Tyler and his colleagues were not the first to articulate a socio-legal rationale for procedural justice, 72 but their formulation has had the greatest influence over the push toward procedural justice in policing.

An overview of the genealogy of police legitimacy theory is helpful for distinguishing it from legal estrangement. Although the research on police legitimacy primarily draws from social psychology, the theoretical underpinnings of the concept (like much of the scholarship on legal legitimacy across domains) 73 usually derive from the work of sociologist Max Weber. 74 From Weber’s standpoint, legitimation is a subjective process: it does not inhere in an authority’s procedures or existence, but is continuously negotiated with subjects, taking into account their views. 75 Weber classified the types of authority that legitimate orders tend to exhibit into three “ideal types ” 76 : charismatic authority, or authority based on perceived personal divinity or exemplariness; traditional authority, based on custom and epitomized by the King; and legal-rational authority, the form of authority found most frequently in modern advanced society, which is based on process and consent. 77 Weber believed that legal-rational authority (the focus of nearly all research on legitimacy today) is, in some ways, the preferred version of legitimation because this legitimation strategy makes clear that, in choosing government through transparent, rational means, human beings are exercising their autonomy and free will. 78 While the threat of violence from the state always lurks, the state’s authority over its citizens primarily comes from the state’s adherence to process. 79

In the legal and political realms, 80 the purpose of legitimacy theory is to understand how the state, from a moral perspective, justifies its power and how, as an empirical matter, it most effectively exercises power over its subjects. 81 State power is the ultimate focal point of legitimacy analysis. 82 The question then becomes, how does the state attain power over its subjects? Theorists such as Habermas refined the concept of legitimacy to emphasize consent, adding a layer of deliberation and positing that legitimacy can be built through dialogue among equal citizens. 83 Along these lines, but with concern about the normative implications of consent, Gramsci argued that governments (and more precisely, capitalist governments) gained legitimacy through ideological and cultural hegemony: legitimation is a bundle of processes that elites use to procure public buy-in to oppressive systems. 84

Regardless of the normative valence of consent, its emphasis in the study of legitimacy has led social psychology research to focus largely on what makes people voluntarily obey and help the state. 85 This consent-based conception of legitimacy falls in line with a focus among policymakers on how to increase voluntary adherence to the law. 86 The empirical work also tries to ascertain how the circumstances under which the community sees legal authority as legitimate might vary across groups.

This focus on consent has produced some insights about the nature of racial divergence in police legitimacy. Two insights have been most central. First, across racial-ethnic groups, people tend to view police as legitimate when they are procedurally just , and people tend to interpret fairness similarly across ethno-racial divides. 87 Second, the primary reason African Americans do not see police as legitimate is because they tend to have more personal experiences in which police officers treat them in a procedurally unjust manner. 88 Although little is known about the specific behaviors and practices that people consider fair or unfair, 89 the police legitimacy literature empirically shows that people want the same type of treatment from police regardless of their race or class. This conclusion means that African Americans’ greater distrust of the police results not from supposed subcultural values or “bad culture,” but instead arises as the product of negative personal experiences.

This insight has driven legal scholarship in several directions. 90 Most central to the analysis of this Essay, police legitimacy scholarship encouraged legal scholars to explore ways that the law might better facilitate procedurally just policing and respond to procedurally unjust policing policies and practices. Steven Schulhofer, Tom Tyler, and Aziz Huq present one of the most fully elaborated applications of legitimacy theory to policing, applying the theory to both conventional and counterterrorism policing. 91 They set forth three policy goals that should emanate from the procedural justice policing model: (1) training officers to treat force as a last resort and “to view every citizen contact as an opportunity to build legitimacy through the tone and quality of the interaction”; 92 (2) eschewing regulation of the police through the blunt instruments of the law (for example, the exclusionary rule) in favor of internal department management policies designed to positively motivate police to treat the public fairly; 93 and (3) in the counterterrorism realm, avoiding the impulse to authorize the use of harsh tactics such as ethno-racial profiling and random checkpoints. 94 Schulhofer, Tyler, and Huq’s approach is distinctively what Rachel Harmon calls “non law,” 95 in the sense that it explicitly rejects legal intervention into policing. Their core suggestions are training, the substance of which is highly discretionary and rarely encoded directly into law, and avoiding litigation-based pathways toward systemic reform, such as the Department of Justice consent decree process. The solutions do not involve creating, changing, or enforcing the law. This means that, even if these approaches are effective, they largely leave intact the legal structure that has given birth to distrust and illegitimacy.

Meares has made several proposals to encourage departments to adopt principles of procedural justice. Conceptually, she has advanced the notion of “rightful policing,” the idea that policing should be designed to maximize both lawful conduct and community perceptions of police legitimacy. 96 Building in part from Schulhofer, Tyler, and Huq’s idea that persuading and incentivizing police to treat people fairly will be more effective than forcing them to do so, Meares’s scholarship has embraced community policing efforts such as Project Safe Neighborhoods in Chicago, Illinois, Project Exile in Richmond, Virginia, and Operation Ceasefire in Boston, Massachusetts. These programs’ methods include organizing meetings with ex-offenders to build relationships and inform them of alternative opportunities to crime, as well as holistic problem-solving approaches, such as legitimacy-based “hot spots” policing (also known as focused deterrence). 97 These approaches are a sort of proactive policing that should, according to their proponents, avoid the pitfalls of earlier forms of broken-windows policing because they now emphasize procedural justice in the micro-level interactions of police contact. 98

Scholars have proposed a variety of other interventions to build legitimacy, as well. For example, some have proposed that law enforcement randomize police stops and searches. In theory, randomization should allow police to engage in hands-on crime prevention without negatively impacting the legitimacy of the system by making specific people, particularly young African American and Latino men, feel targeted. 99 Other scholars have incorporated these concerns about spatial and racial distribution of procedurally unjust policing into Fourth Amendment arguments. They propose that courts should consider whether officers were making an individualized determination of suspicion, as constitutionally required, 100 or rather engaging in a collective determination of suspicion based on race and geography. 101 Other recent work proposes using a disparate impact framework, similar to that used in Title VII analysis, to assess the spatial and racial impacts of stop-question-frisk. 102

The greatest strength of the police legitimacy approach is its deceptive simplicity. Its two core ideas—that people will accept unfavorable police decisions so long as the preceding processes are perceived to be fair, and that the police should treat all people, including African Americans and the poor, with dignity and respect in order to be more effective at the work of crime deterrence —are marked deviations from the prevailing wisdom about policing that preceded legitimacy theory. For example, as noted above, the Kerner Commission Report partly blamed African Americans’ cynicism about the police on the harsh tactics that police deemed necessary to control crime in predominantly black inner-city neighborhoods. 103 In one of the earliest in-depth studies of urban police, William A. Westley found that the police officers he studied tended to view both African Americans and residents of poor neighborhoods as requiring a fundamentally different type of policing than other groups because those two groups would “respond only to fear and rough treatment.” 104 Officers today are not as likely to overtly express racial animus, but they might use different language focused on class and “culture” to make a similar point. 105 Justifications for race- and class-differentiated policing partly derive from a view that police tactics must vary by the type of community in order to be effective. The procedural justice approach is a partial corrective to that common wisdom.

However, police legitimacy is not all-encompassing, and it is often disturbingly oversimplified in practice.Policymakers and police department leaders attempting to apply the theory often condense it to empirically informed officer politeness. 106 Most legitimacy scholars would not claim that the lack of legitimacy is the sole problem in the relationship between law enforcement and African American and poor communities, or that procedural justice is the only solution needed. 107 Yet much of the current reform conversation has drawn heavily on legitimacy theory and the procedural justice approach as if they are silver-bullet solutions to today’s policing crisis. Reformers have done so in part because the proposals that emanate from the procedural justice perspective, such as improved officer training, 108 are relatively easy for police agencies to implement, relatively inexpensive, and relatively noncontroversial—while offering some real, on-the-ground benefits to civilians who encounter the police. 109

If the solution to today’s social and legal policing problems is training, the path forward is clear. Yet some scholars have worried that without an emphasis on the problem of collective estrangement through social and racial control, the procedural justice solution could paradoxically teach officers more effective ways to discriminate and violate privacy. 110 Indeed, Fourth Amendment jurisprudence on the voluntariness of searches foregrounds this danger. Courts often mention the politeness or courtesy of officers when using a totality of the circumstances analysis to decide whether a warrantless search was voluntary, at times debating the relative importance of politeness in the voluntariness analysis. 111 Thin conceptions of procedural justice could produce what Jeremy Bentham called “sham security,” 112 leaving some individuals with a vague sense that they have been treated justly while neglecting more fundamental questions of justice.

An expanded theoretical approach understands distrust as a problem of legal estrangement: a marginal and ambivalent relationship with society, the law, and predominant social norms that emanates from institutional and legal failure. In the following Part, I discuss estrangement theory and its distinctions from police legitimacy theory in greater detail. The legal estrangement perspective can provide a fresh perspective in research and policy on the extent to which African Americans and people who live in high-poverty communities feel a sense of solidarity with law enforcement and other legal institutions. Moreover, this approach could help scholars and policymakers imagine new ways to promote solidarity and social inclusion through law and policy.

B. A Crisis of Estrangement

While legitimacy theory has its roots in Weber, 113 the distinctive elements of legal estrangement theory are rooted in Émile Durkheim. For Durkheim, the central project of modern society is to maintain “organic solidarity,” defined as social cohesion based on fulfillment of the different functions each person serves within society. 114 Ideally, law’s function is to create and maintain social cohesion. Law is not understood as an end in itself, nor solely a means of bodily control. 115 In the Durkheimian view, the purpose of criminal justice is to restore those who break the law, with the ultimate goal of increasing social cohesion by reinforcing moral and legal norms. 116 A society that does not reinforce moral norms, and does not promote social trust, leaves its inhabitants in a state of anomie, with broken social bonds.

Although Durkheim originated the concept of anomie, the idea gained greater precision (and liberation from its purely pro-state perspective) in the work of Robert Merton. For Merton, anomie is “a breakdown in the cultural structure” of society. 117 These breakdowns are particularly likely to occur “when there is an acute disjunction between the cultural norms and goals and the socially structured capacities of members of the group to act in accord with them.” 118 In other words, cultural structures break down when, despite a group’s adoption of “mainstream” cultural norms and goals, certain aspects of the social structure prevent them from being able to act in ways that support those norms and goals. Although the suitability of Durkheim’s comprehensive view of law and punishment for modern contexts is questionable, 119 the broadest reading of anomie theory—that the purpose of the legal system is to create a cohesive and inclusive society, and that a broken social order leaves some people without the resources for full social membership—is at the root of legal estrangement theory.

A century after Durkheim originated the anomie concept and decades after Merton refined it, sociologists Robert Sampson and Dawn Jeglum Bartusch offered “legal cynicism” as a framework for understanding how residents of predominantly African American neighborhoods in Chicago thought about the law and its enforcers. 120 Sampson and Bartusch defined legal cynicism as“‘anomie’ about law.” 121 Anomie is more than distrust. Instead, it is a sense that the very fabric of the social world is in chaos—a sense of social estrangement, meaninglessness, and powerlessness, often a result of structural instability and social change. 122 It is a sense founded on legal and institutional exclusion and liminality. 123 Perhaps the strongest articulation of legal anomie comes from eminent ethnographer Elijah Anderson, who credited the tendency to use extra-legal forms of violence among some of his research subjects in inner-city Philadelphia to “the profound sense of alienation from mainstream society and its institutions felt by many poor inner-city black people . . . . ” 124 In contrast, law that is well designed and properly enforced should reassure community members that society has not abandoned them, that they are engaged in a collective project of making the social world.

One concern with labeling “anomie about law” as “legal cynicism” is that the word “cynicism” suggests that the attitudinal perspective of communities is the issue of interest rather than the process that led to a cultural orientation toward distrusting the police. The “legal cynicism” term works for the approach taken by Sampson and Bartusch as well as that of Kirk and Papachristos, as both seek to link “legal cynicism” (as measured in a survey) with a number of outcomes. However, anomie refers not only to the subjective feeling of concern; it is also meant to implicate a particular set of structural conditions that produced that subjective feeling. 125 I use “legal estrangement” in this Essay to better capture the fullness of the idea of anomie about law. Legal estrangement can help scholars understand situations where, even despite the embrace of legality by African Americans and residents of high-poverty neighborhoods, and regardless of the degree to which they embrace law enforcement officials as legitimate authorities, they are nonetheless structurally ostracized through law’s ideals and priorities.

The theoretical and empirical genealogies of legitimacy and legal cynicism reveal important distinctions. First, the overwhelming majority of the legitimacy research has sought to describe a general perception of law enforcement and legal authority, based on a representative sample of the public. 126 In contrast, scholarship on legal cynicism—the attitudinal portion of legal estrangement theory—has generally sought to describe a contextualized, ecological view of law enforcement. This scholarship has particularly focused its efforts on understanding the nature of the fraught relationship between African Americans and high-poverty communities on the one hand, and the police on the other. 127

Legal estrangement is a cultural and systemic mechanism that exists both within and beyond individual perceptions. It is partly representative of a state of anomie related to the law and legal authorities, and it interacts with legal and other structural conditions—for example, poverty, racism, and gender hierarchy—to maintain segregation and dispossession. The salience of a targeted, collective, community-oriented analysis is even greater when seeking to understand the realities that gave birth to Black Lives Matter. Many scholars and advocates have argued that African Americans are particularly likely to assess the legitimacy, effectiveness, and justness of institutions based on their beliefs about how these institutions treat African Americans as a group , and not just their individual experiences. 128

A person could simultaneously see the police as a legitimate authority (believing that individuals should obey officer commands in the abstract) and feel estranged from the police (believing that the legal system and law enforcement, as the individual’s group experiences these institutions, are fundamentally flawed and chaotic, and therefore send negative messages about the group’s societal belonging). 129 Some scholarship on the legal mistrust of poor African Americans could be misread to suggest that a large subset of this group possesses values that are antithetical to law-abiding behavior, almost as if these individuals do not care what the law is and do not believe they should be bound by it. A better-supported interpretation is that many poor African Americans might see police as a legitimate authority in the ideal, and might even empathize with some police officers’ plight, but they find the police as a whole too corrupt, unpredictable, or biased to deem them trustworthy. 130 Even as they accept the ideal vision of the police as the state-authorized securers of public safety, their nonideal working theory might be, as earlier research suggests, that the police are “just another gang.” 131

Estrangement theory can improve legitimacy theory in three main ways. First—certainly in its initial stages—legitimacy theory has emphasized whether people feel voluntarily obligated to obey or cooperate with law enforcement. The theoretical starting point of legitimacy analysis is whether and how the state maintains and exercises its power. In an analysis based on legal estrangement theory, increasing the power of the state bears at most a spurious relationship to the outcome of concern, which is social inclusion across groups. From a robust legal estrangement perspective, the law’s purpose is the creation and maintenance of social bonds. An emphasis on inclusion implies concerns not only about how individuals perceive the police and the law (and thus whether those individuals cooperate with the state’s demands), but about the signaling function of the police and the law to groups about their place in society. While legitimacy theorists might acknowledge the value of these sorts of community feelings, they are not those theorists’ key variables of interest. 132 Shifting the orientation of legitimacy theory from governmental power to social inclusion is one way that theory can better capture the concerns of activists in the era of Black Lives Matter.

Second, given its origins in legal cynicism theory, a legal estrangement perspective emphasizes cultural orientation toward the police rather than individual attitudes about the police. A cultural inquiry is concerned with the symbolic and structural meaning of the police to particular groups of people, as opposed to those individuals’ opinions about police interactions. People’s opinions about their interactions with the police, their beliefs about whether the police in general tend to be helpful, and the symbolic meanings they attach to the police can be sharply divergent from each other. 133

Third, while most legitimacy theorists treat individuals as their unit of analysis and theorization, the legal estrangement framework is ultimately focused on groups and communities.Even as studies are unavoidably conducted by looking at individual experiences, the broader concern of legal estrangement is with understanding people in situ. Viewing distrust of the law as a problem of social psychological legitimacy suggests more micro-level solutions to the problem, centered on changing individual perceptions of the law and law enforcement. Conversely, seeing distrust as a problem of legal estrangement (legal anomie) focuses solutions on unsettling characteristics of the social structure. The goal is to enable marginalized groups to align their values of law-abiding and respect for law enforcement with their lived experiences and strategies for interacting with law enforcement.

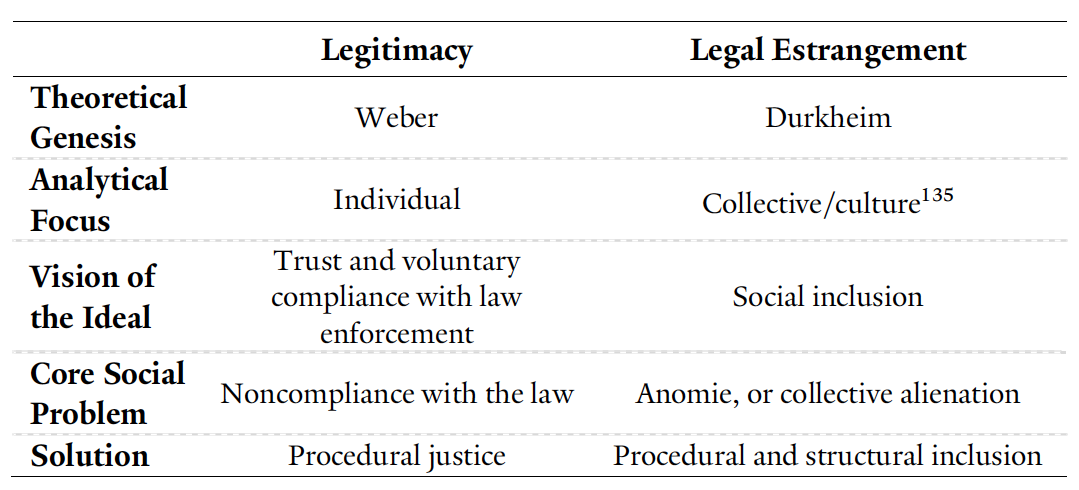

table 1. legitimacy and legal estrangement 134

iii. the legal socialization

To more clearly illustrate some on-the-ground improvements that a legal estrangement perspective offers to legitimacy theory, this Part presents a portrait of Shawna. Shawna is one of sixty-four participants in Hearing Their Voices: Understanding the Freddie Gray Uprising , a study I led a few months after the Freddie Gray incident and subsequent unrest in Baltimore. 137 The purpose of this profile is to articulate, in a more grounded way, key distinctions between what scholars and policymakers usually learn from a police legitimacy perspective and what they can learn from a legal estrangement perspective. Shawna 138 has a complex, but largely distrustful, perspective on the police. This Part and the vignettes in Part IV capture, in a more textured fashion, the multitude of factors that can contribute to legal estrangement. 139

Growing up in West Baltimore’s Gilmor Homes in the mid-aughts, Shawna developed an affinity for chess, American Sign Language, and most of all, pick-up basketball. “I just played basketball all day, every day. Nine o’clock in the morning until nine o’clock at night when my mom was calling me to get off the court, that’s where I was at.” 140

During Baltimore’s sticky summers—the time of year when the rate of violent crime is at its apex 141 —Shawna sought freedom and community on Sandtown-Winchester’s asphalt basketball courts. One can imagine Shawna sucking in the steamy air, wearing basketball shoes not unlike the red and white Nikes she is wearing now, teasing her opponents, being a kid. “I wanted to stay outside as long as I can,” she explained. “Stay outside until nine or ten o’clock, in the summer time especially, yes. That’s when the most violence happens, but that’s when the most fun happens.” Shawna understood pleasure more viscerally than danger, despite everything she had seen.

One of Shawna’s first virtues was vigilance. She learned early how to manage the potentially deadly situation of being outdoors in the Gilmor Homes. “Just being so young, you have to be aware. I mean, you can have fun, but just be aware of what’s really going on around you. There was so much drug activity. But, being so young, I didn’t really pay a lot of attention because I was just worried about having fun.”

Despite the pestilence of untimely death that—then and now—marks her neighborhood, 142 Shawna has thus far been spared the memory of seeing a human being die. But she is familiar with the pop-pop-pop of gunshots interrupting a basketball game. She can still hear the hum of an open-windowed truck rolling closer while prowling for targets, the screams of neighbors recognizing a familiar horror, the thumps of her playmates’ chests hitting the ground seeking safety, and the thuds of their shoes rapidly beating the hot asphalt where they had been dribbling a ball moments earlier. She remembers that a sudden paralysis afflicted her limbs on those occasions. She remembers that her mother would run to her, corral her. “Somebody would get shot. Somebody would get killed. Somebody would get stabbed. Outside my house, in front of my house, on the basketball court, where I spent most of my time there, for real.”

Shawna’s mother Denise was, in Shawna’s estimation, “paranoid.” Every now and then, Denise got fed up and called the police about various neighborhood disturbances. “She’s a good person,” Shawna explained. But Denise avoided calling the police from her own phone and instead went to a neighbor’s home to call. To be sure, Denise sometimes called police from a neighbor’s phone because her own phone was disconnected. But Shawna suspects that the more usual reason Denise called from her neighbor’s phone was so the call would come from a number other than hers, making it more difficult for police and potential retaliators to learn that she was the snitch. “She had to call from some [other] number because she just—it was unsafe for her.” People can call the police “anonymously,” 143 but Denise suspected the police would find out who she was anyway, and that they would be too careless to protect her identity.

Denise warned Shawna about crime in the neighborhood and kept Shawna indoors as much as the active, extroverted girl could tolerate. Denise also warned Shawna about the neighborhood’s police, petrified by her daughter’s awe of them.

“[W]hen I was little,” Shawna recalled, “I used to idolize the police. And I used to be like, ‘Oh, can I be like you when I grow up? What is it that you do?’ Asking them a whole bunch of questions.” Her mother urged her to stay away from police officers. Once, when Shawna was about eight years old, she was chatting with two white police officers who she thinks were in the neighborhood to investigate drug activity. As Shawna remembers it, she asked the officers what they do, how she could become a police officer, and so on. “I was a serious young lady,” Shawna joked. Denise saw Shawna with the officers and panicked. “Get over here! Get over here! Get over here, girl!” Shawna asked, “[W]hat did I do?” Denise continued, agitated. “Who told you to talk to them? They can do anything to you. They can take you and kill you!” Shawna was perplexed. “They’re police. Why would they just take me and kill me?”

Over the decade or so since that incident, Shawna’s once-pristine view of police has grown ever more tainted. This tarnishing process has been propelled not only by her personal experiences, but also through witnessing the encounters of her friends and neighbors, hearing about other incidents through television and social media, and gaining folk wisdom from family and older community members. For example, several years before the Daniel Holtzclaw case broke, 144 as a pubescent girl, Shawna learned from her grandmother that the police could rape her.

I don’t know the whole story, but my grandma told me how one of the police in my community . . . some man had taken this little girl. She was about twelve. I don’t know if she was missing or if he just took her anyway. He took her and he raped her in the back of the police station and they caught it on camera. Then my grandmother told me about it. I was like twelve at the time, which was just a couple of years [after the rape]. I was like, “Wow.”

Shawna’s confusion grew. “The police is supposed to have power and supposed to be using it for good.” But the police also “did that to that little girl. It’s just terrible.” That story, funneled through her beloved grandmother, is now embedded in her psyche and colors her more recent experiences with and observations of police officers. “That just made me think twice about the police ever since then. I just don’t know.”

The case Shawna is likely referencing involved William D. Welch, a former Baltimore police officer who entered an Alford plea 145 to a charge of misconduct in office in early 2008, when Shawna was ten. 146 After another officer arrested a sixteen-year-old girl based on an open warrant for prostitution, Welch allegedly offered to dispose of marijuana that was in her possession if she sexually serviced him. According to the accuser, she and Welch flushed the marijuana down a police station toilet and returned to the interview room, where she complied with his conditions. 147 Prosecutors originally charged Welch with second-degree rape. However, after the police department’s Evidence Control Unit misplaced much of the physical evidence against Welch, prosecutors offered, and Welch accepted, a plea deal. 148 Welch thus avoided prison. A judge sentenced Welch to a suspended ten-year prison term after three years of probation and ordered him to resign from the Baltimore Police Department. 149

But Shawna might have been talking about a different case. There were other prominent rape cases against Baltimore police officers in roughly the same time period. Like the Welch case, the facts of those cases do not perfectly align with the story lodged in Shawna’s mind today. 150

Shawna’s understanding of the police grew darker still through encounters and observations at the bus station near the iconic Mondawmin Mall, arguably West Baltimore’s central hub. Mondawmin, one of the city’s oldest enclosed shopping malls, is more than a retail center. It is also the nerve center for ten West Baltimore bus lines and the location of government social services offices and various health clinics. 151 Inside the mall, uniformed private security guards are tasked with maintaining Mondawmin’s security, while on the outside, Western District police officers handle the job. Shawna does not distinguish between the public and private police. She just knows that when she is in or near Mondawmin, she encounters hostile people in uniform. 152 Shawna reports several negative encounters there, but nothing that would earn the attention of journalists, researchers, or most advocates. She has experienced, at most, (possibly idle) threats—that the next time a police officer sees her, he will mace or even arrest her. These threats, these forceful words, would not register as “uses of force” in the most sophisticated studies of police encounters. 153 Yet they have constrained her movement. The grind of injustice has led Shawna to avoid Mondawmin as much as possible, though the mall’s ubiquity makes it hard to fully escape.

I stopped going to Mondawmin because the police up there are rude. I mean, I know you’re trying to keep order and peace, but you don’t have to disrespect me and threaten me every five seconds. They threatened to mace people if they don’t get to their bus stop. Then the man told me he was going to arrest me because I was talking to my home girl and I wouldn’t get on the bus. It wasn’t my bus. I was at the bus stop talking to her. Why are you threatening to arrest me?

Shawna claims that the officer followed her and her friend after they began to walk away. “He kept getting smart with his little cowboy boots. I was just like, ‘Who are these police?’ Like, where did they come from?” Shawna had a few stories from Mondawmin, including watching a young man get arrested who “wasn’t probably all innocent” but in her view “wasn’t doing anything he wasn’t supposed to be doing.”

The Gilmor Homes, where Shawna spent the first sixteen of her nineteen years, has recently been in the national media as the home of Freddie Gray, the twenty-five-year-old Baltimore man who died in police custody on April 19, 2015. 154 Mondawmin was a starting site of the ensuing “riots.” 155 Shawna was nearby when the riots broke out, trying to head to a friend’s house for spaghetti.

Shawna’s views on the riots vacillate from empathy for the good police officers who have been unfairly demonized, to frustration at the destruction of already limited West Baltimore institutions, to condemnation of unjust police practices, to pragmatic belief in the necessity of the police. “I felt bad for the police though, when they were rioting. They were throwing bricks at the police cars and all this other stuff . . . . First of all, you’re going to need them. Second of all, every police officer is not bad.” Belying usual portrayals of people like Shawna in the media and in most research, Shawna readily acknowledges the humanity of officers and the heterogeneity of police forces. “[H]e’s got kids too. He’s got to live too. He’s got to eat too, and if he wanted to be a police officer, that doesn’t mean every police officer is bad.” Still, “some of them have to go.”

Despite the negative representation of Baltimore youth in the national media during the riots and what she sees as the inherent wrong of riotous behavior, Shawna has ambivalently started to believe that the riots were a necessary catalyst for the police officers to face criminal charges. 156 “It might not be right to riot, but if they wouldn’t have done that, they would never have pressed charges on [the police officers] . . . . It might have been terrible for our community and made us look a mess, especially to the nation, to everybody who saw it.” Shawna is upset that some leaders used the controversial term “thugs” when referring to Baltimore rioters. Despite not participating in the riot herself, Shawna felt that the label was directed at young African American West Baltimoreans in general. “It really hurt my feelings that they called us thugs. I saw a video on that too.”

“They” included President Obama, who described the rioters as “criminals and thugs who tore up the place”; 157 Maryland governor Larry Hogan, who depicted them as “gangs of thugs whose only intent was to bring violence and destruction to the city”; 158 Baltimore City Council President Bernard C. “Jack” Young, who distinguished between legitimate Sandtown-Winchester residents and “thugs seizing upon an opportunity”; 159 and Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, who lamented that young rioters were disrespecting the legacy of people who had fought for the city in the past. “Too many people have spent generations building up this city for it to be destroyed by thugs who, in a very senseless way, are trying to tear down what so many have fought for,” Rawlings-Blake said. 160 After extensive criticism, Rawlings-Blake and Young backed away from using the term “thug.” 161 The White House stood behind the President’s choice of words. 162

Talking with us only a few weeks after the murder of nine people in Charleston, South Carolina’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, 163 Shawna compared Charleston officers’ humane treatment of shooter Dylann Roof with Baltimore officers’ aggression toward Freddie Gray. She shook her head with disgust. “They bought him Burger King. They bought him Burger King, but they couldn’t even get Freddie Gray to a hospital.” 164 I asked Shawna how she knew about all of these things—the details of Freddie Gray’s arrest, the series of “thug” speeches, and the Burger King trip for Dylann Roof. “It was on Facebook. A lot of things are on Facebook,” Shawna pointed out.

Later, I asked her, “Do you want to be a police officer anymore?” “Whoa,” Shawna chuckled, “I gave that dream up.” Now entering her final year of high school, Shawna desultorily explained that her goals for the next several years are to “just better myself in the years to come. That’s what I want to do. I just want to be better.”

The legitimacy perspective would offer an incomplete diagnosis of the unsettled relationship between the police and someone like Shawna—a thoughtful young woman who has never had any serious police encounter, who has managed to avoid getting a criminal record, and who is a general law-abider, wanting to trust the police but convinced that the police are not trustworthy for people like her. Shawna is generally compliant with the law and believes police officers should be respected. She thinks that it is good to help police officers, and she appreciates that her mother would stealthily report crime. From a law enforcement perspective, people like Shawna are allies and assets to the community. Shawna behaves like someone who views the police as a legitimate legal authority.

Yet Shawna’s views also reflect a deep sense of alienation about police. She stopped going to the mall to avoid interacting with the officers there. She abandoned her childhood dream of becoming a police officer, even though she possesses the presence, personality, and background to be an excellent law enforcement official. She fears that police might kill or sexually assault someone like her: a young, low-income black woman who lives in West Baltimore. Although Shawna sees the law and its enforcers as worthy of obedience as a theoretical matter, she does not believe that law enforcement officials see her, and people like her, as a true part of the polity. She is nothing more than a “thug.” This understanding of her group’s place in the world does not lead to law-breaking or noncooperation, as a legitimacy perspective might predict. 165 Yet her words nonetheless reveal a cleavage, or estrangement, from the enforcers of the law. Her story reveals that the empirical outcome that legitimacy theory is best used to explain is the wrong outcome: Shawna’s problem is not noncompliance, but symbolic community exclusion.

iv. a tripartite theory of legal estrangement

To this point, this Essay has argued that scholars and policymakers should understand persistent police distrust among African Americans and residents of high-poverty communities as a problem of legal estrangement, a cultural orientation about the law that emanates from collective symbolic and structural exclusion—that is, both subjective and objective factors. In this Part, I further define legal estrangement theory. I argue that legal estrangement is a product of three socio-legal processes: procedural injustice, vicarious marginalization, and structural exclusion. All of these processes are supported in the empirical literature, although their primary justifications emerge from theory. Below, I explain each process in greater detail, drawing upon the literature and offering real-world illustrations from qualitative data.

A. Procedural Injustice

Building from the legitimacy and procedural justice scholarship described in Part II, I argue that experiences in which individuals feel treated unfairly by the police are one key provocateur of legal estrangement. The procedural injustice component operates at the individual and attitudinal level but, writ large, expands to the cultural level. 166 urvey research indicates that a feeling that the police have behaved disrespectfully feeds into an overall disbelief in the legitimacy of the law and law enforcement. 167 The path to legitimacy, from a procedural justice perspective, requires “treatment with dignity and respect, acknowledgment of one’s rights and concerns, and a general awareness of the importance of recognizing people’s personal status and identity and treating those with respect, even while raising questions about particular conduct.” 168

Consider the example of Justin, 169 an eighteen-year-old African American man living in Northeast Baltimore who is heading to a small religious college out of state on an athletic scholarship. (He had wanted to aim for an Ivy League school because his high school grades were strong, but according to him, his SAT score was nearly 100 points shy of the baseline.) Justin’s police encounters typify and bleed into a general feeling that he is socially and politically powerless. The criminal justice system “just get[s] so irritating, just to know you can’t do nothing about it,” he groused. “You have a voice, but then it’s your voice and billions of other voices. If everybody’s not together and its one side against the other, your voice basically doesn’t matter. It just gets so frustrating how disrespectful somebody with high power can be. It just gets annoying.”

To illustrate his point about disrespect from people in power, Justin told us about his most recent police encounter. 170 He and his friends were in Hunt Valley, a small suburb just north of Baltimore city limits, known for its expansive, recently reinvigorated outdoor shopping mall. At around 11:30 PM, as they walked toward the light rail station that would carry them home to West Baltimore, they were stopped by a police officer. They were walking in the street along one side; they felt more comfortable walking in the road than on the sidewalk because there were woods on either side of the street. “It’s night time. I don’t want to be over there. For one, you got to think, there’s mosquitoes, ticks, and stuff like that. People could be hiding over there.” 171 According to Justin, the officer pulled them over, questioned them about what they were doing, and ran all of their information. The officer ultimately only gave them warnings for walking in the street. Justin repeated the charge, still with a hint of disbelief. “For walking in the street. For walking in the street!” 172

What irked Justin more than the warning, though, was the police officer’s apparent disregard for their travel timetable. While they were stopped, Justin and his friends told the officer that they were on their way to the light rail station and that they needed to get there quickly because the rail stops running at midnight. They were not sure when the last train to Baltimore would depart, so they were trying to get there as soon as possible. The officer assured them that they would make their train. Yet by the time he checked their information and issued their warning tickets, it was approximately 12:05 AM. Justin’s bitterness about missing the train had not yet faded. “When I say they didn’t let us go until about 12:05! They didn’t let us go until 12:05 and only gave us warnings—for walking in the street.”

Justin now expects that the police will not value his time. He has resigned himself to this signal of his own inconsequentiality.

Whatever it is, whatever you need, go ahead, because now I know we on your time, now. Once you stop me, even if I did nothing wrong, we on your time. So I might as well just get it over with, let you do what you’re going to do. I know you’re going to be disrespectful. I’m prepared for that. I know you’re going to be disrespectful. It’s up to me how I’m going to react to that.

When asked if he had other experiences like that one, Justin could not answer precisely. He knows that he has been stopped many times, but he tries not to dwell on those encounters, preferring to focus on school, work, sports, and “females.” He also tries to minimize the importance of race in this unnamed number of police encounters.“I just hate the way how they can be so disrespectful to us like we’re not human or nothing. It’s like this stereotype where you think a young African American—or not even a young African American, just a young individual, period, just walking, you think they’re up to something.” He tries instead to look at his police encounters from a power and authority perspective, in part just to avoid the stress of seeing the world as racist. 173 “People who have never had power before, they finally get power, and they want to abuse it. I try my best not to look at it as a racial thing because I know that’s only going to make me mad and stress me out. So, I try to look at it from all angles.”

Justin is an ambitious young man, one of the few in the sample who had the good fortune of having solid college plans. He has carefully curated his group of friends to include only those who “keep each other focused,” mostly fellow college-bound athletes. If Justin had been answering a survey about legal compliance, there is a reasonable chance that he would have marked that he adheres to most laws and believes that it is important to do so. Yet he deeply distrusts the police, partly because he believes that they treat him and other young Baltimoreans with disrespect in order to assert their authority. 174 In addition, he has serious doubts about whether the police would be helpful if he needed them, saying that no matter what the issue was, he would not call the police: “I call the police—I’m not doing nothing for nobody. If I call the police, there’s a possibility they might turn on me.” Those feelings of being both under surveillance and unprotected have created a devil’s brew of legal estrangement such that even a youth like Justin, who has thus far been able to avoid the criminalization process common for young men of color, 175 would rather pursue extra-legal help with neighborhood concerns than trust in the police.

As for the midnight police encounter: on the facts as Justin presented them, there is little doubt that the stop was lawful. The officer saw Justin and his friends walking in the middle of the street in violation of Maryland state law. 176 He stopped them, asked them what they were doing, ran their identification (apparently finding no open warrants), and sent them on their way with only a warning. Justin had two problems with the stop: he feels that the very reason they were stopped was generalized suspicion of young people (and possibly young black people), and that the officer did not care that this stop caused them to miss their ride home.This stop was less awful than it could have been, but it factors heavily into Justin’s concerns about the police and the larger social structure.

Justin’s story illustrates how procedural injustice, even at a relatively minor level, creates and reinforces legal estrangement. The legitimacy literature, though concerned with procedural injustice, does not offer an account that illuminates Justin’s concerns about the police: he willingly complied with the officer’s commands, not out of fear but from a sense that, generally speaking, he ought to obey the instructions of law enforcement officers. However, the experience nonetheless contributed to his sense that there is a schism between young Baltimoreans and the police. Yet procedural injustice is only one leg of legal estrangement’s three-legged stool. The benefits of a legal estrangement perspective emerge more clearly when considering the additional processes of vicarious marginalization and structural exclusion.

B. Vicarious Marginalization

The second contributor to legal estrangement discussed here is vicarious marginalization: the marginalizing effect of police maltreatment that is targeted toward others. Although the literature on legal socialization, legitimacy, and legal cynicism vaguely acknowledges the influence of police experiences within people’s social networks and the impact of highly publicized misconduct on cultural orientations about the law, the scholarly treatment of vicarious experience is thin relative to the treatment of personal experience. 177 This deficit is, in part, a disciplinary artifact. Most legal socialization and legal legitimacy research draws from social psychology, which by definition focuses primarily on understanding individuals’ internal lives and how they relate to their personal interactions and behaviors. 178 The legitimacy literature has been interested in generalized views and “societal orientations,” but it focuses mostly on whether one can generalize from personal experiences instead of whether and how impersonal, vicarious experiences also contribute to social orientations. 179 Sociological and socio-legal theory, in contrast, provides a theoretical grounding for the idea that other people’s negative experiences with the police, whether those people are part of one’s personal network or not, feed into a more general, cultural sense of alienation from the police. 180 Legal estrangement is born of the cumulative, collective experience of procedural and substantive injustice.