Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Future of the Internet IV

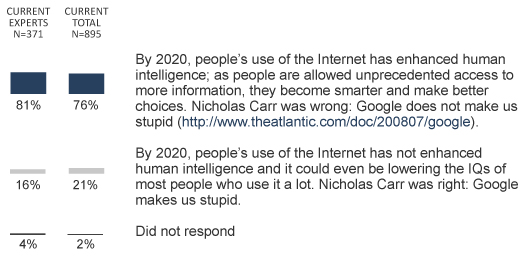

- Part 1: A review of responses to a tension pair about whether Google will make people stupid.

Table of Contents

- Part 2: A review of responses to a tension pair about the impact of the internet on reading, writing, and the rendering of knowledge

- Part 3: A review of responses to a tension pair about how takeoff technologies will emerge in the future

- Part 4: A review of responses to a tension pair about the evolution of the architecture and structure of the Internet: Will the Internet still be dominated by the end-to-end principle?

- Part 5: A review of responses to a tension pair about the future of anonymity online

The future of intelligence

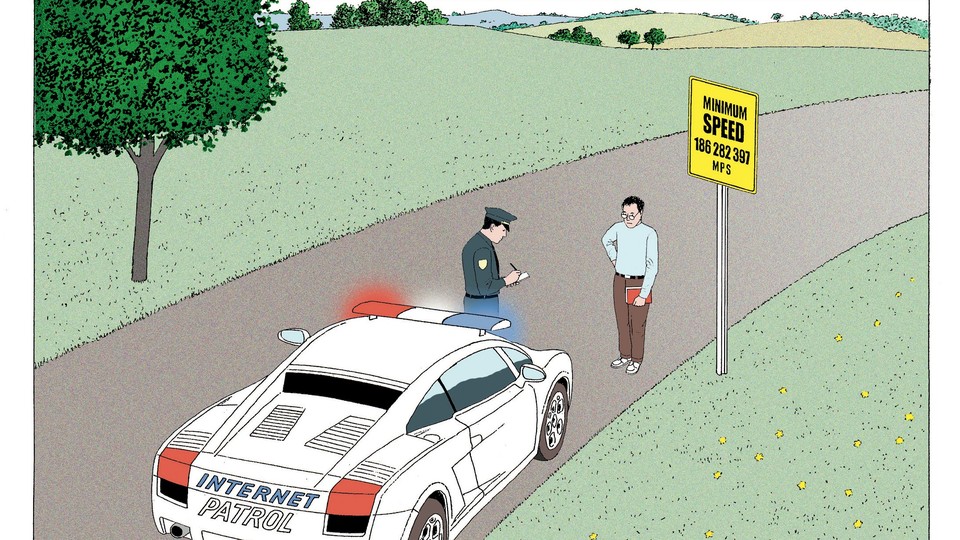

Eminent tech scholar and analyst Nicholas Carr wrote a provocative cover story for the Atlantic Monthly magazine in the summer of 2008 1 with the cover line: “ Is Google Making us Stupid ?” He argued that the ease of online searching and distractions of browsing through the web were possibly limiting his capacity to concentrate. “I’m not thinking the way I used to,” he wrote, in part because he is becoming a skimming, browsing reader, rather than a deep and engaged reader. “The kind of deep reading that a sequence of printed pages promotes is valuable not just for the knowledge we acquire from the author’s words but for the intellectual vibrations those words set off within our own minds. In the quiet spaces opened up by the sustained, undistracted reading of a book, or by any other act of contemplation, for that matter, we make our own associations, draw our own inferences and analogies, foster our own ideas…. If we lose those quiet spaces, or fill them up with ‘content,’ we will sacrifice something important not only in our selves but in our culture.”

Jamais Cascio, an affiliate at the Institute for the Future and senior fellow at the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, challenged Carr in a subsequent article in the Atlantic Monthly ( http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200907/intelligence ). Cascio made the case that the array of problems facing humanity — the end of the fossil-fuel era, the fragility of the global food web, growing population density, and the spread of pandemics, among others – will force us to get smarter if we are to survive. “Most people don’t realize that this process is already under way,” he wrote. “In fact, it’s happening all around us, across the full spectrum of how we understand intelligence. It’s visible in the hive mind of the Internet, in the powerful tools for simulation and visualization that are jump-starting new scientific disciplines, and in the development of drugs that some people (myself included) have discovered let them study harder, focus better, and stay awake longer with full clarity.” He argued that while the proliferation of technology and media can challenge humans’ capacity to concentrate there were signs that we are developing “fluid intelligence—the ability to find meaning in confusion and solve new problems, independent of acquired knowledge.” He also expressed hope that techies will develop tools to help people find and assess information smartly.

With that as backdrop, respondents were asked to explain their answer to the tension pair statements and “share your view of the Internet’s influence on the future of human intelligence in 2020 – what is likely to stay the same and what will be different in the way human intellect evolves?” What follows is a selection of the hundreds of written elaborations and some of the recurring themes in those answers:

Nicholas Carr and Google staffers have their say

“I feel compelled to agree with myself. But I would add that the Net’s effect on our intellectual lives will not be measured simply by average IQ scores. What the Net does is shift the emphasis of our intelligence, away from what might be called a meditative or contemplative intelligence and more toward what might be called a utilitarian intelligence. The price of zipping among lots of bits of information is a loss of depth in our thinking.”– Nicholas Carr

[the institution of time-management and worker-activity standards in industrial settings]

“Google will make us more informed. The smartest person in the world could well be behind a plow in China or India. Providing universal access to information will allow such people to realize their full potential, providing benefits to the entire world.” – Hal Varian, Google, chief economist

The resources of the internet and search engines will shift cognitive capacities. We won’t have to remember as much, but we’ll have to think harder and have better critical thinking and analytical skills. Less time devoted to memorization gives people more time to master those new skills.

“Google allows us to be more creative in approaching problems and more integrative in our thinking. We spend less time trying to recall and more time generating solutions.” – Paul Jones , ibiblio, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

“Google will make us stupid and intelligent at the same time. In the future, we will live in a transparent 3D mobile media cloud that surrounds us everywhere. In this cloud, we will use intelligent machines, to whom we delegate both simple and complex tasks. Therefore, we will loose the skills we needed in the old days (e.g., reading paper maps while driving a car). But we will gain the skill to make better choices (e.g., knowing to choose the mortgage that is best for you instead of best for the bank). All in all, I think the gains outweigh the losses.” — Marcel Bullinga , Dutch Futurist at futurecheck.com

“I think that certain tasks will be “offloaded” to Google or other Internet services rather than performed in the mind, especially remembering minor details. But really, that a role that paper has taken over many centuries: did Gutenberg make us stupid? On the other hand, the Internet is likely to be front-and-centre in any developments related to improvements in neuroscience and human cognition research.” – Dean Bubley, wireless industry consultant

“What the internet (here subsumed tongue-in-cheek under “Google”) does is to support SOME parts of human intelligence, such as analysis, by REPLACING other parts such as memory. Thus, people will be more intelligent about, say, the logistics of moving around a geography because “Google” will remember the facts and relationships of various locations on their behalf. People will be better able to compare the revolutions of 1848 and 1789 because “Google” will remind them of all the details as needed. This is the continuation ad infinitum of the process launched by abacuses and calculators: we have become more “stupid” by losing our arithmetic skills but more intelligent at evaluating numbers.” – Andreas Kluth, writer, Economist magazine

“It’s a mistake to treat intelligence as an undifferentiated whole. No doubt we will become worse at doing some things (‘more stupid’) requiring rote memory of information that is now available though Google. But with this capacity freed, we may (and probably will) be capable of more advanced integration and evaluation of information (‘more intelligent’).” – Stephen Downes, National Research Council, Canada

“The new learning system, more informal perhaps than formal, will eventually win since we must use technology to cause everyone to learn more, more economically and faster if everyone is to be economically productive and prosperous. Maintaining the status quo will only continue the existing win/lose society that we have with those who can learn in present school structure doing ok, while more and more students drop out, learn less, and fail to find a productive niche in the future.” – Ed Lyell , former member of the Colorado State Board of Education and Telecommunication Advisory Commission

“The question is flawed: Google will make intelligence different. As Carr himself suggests, Plato argued that reading and writing would make us stupid, and from the perspective of a preliterate, he was correct. Holding in your head information that is easily discoverable on Google will no longer be a mark of intelligence, but a side-show act. Being able to quickly and effectively discover information and solve problems, rather than do it “in your head,” will be the metric we use.” – Alex Halavais , vice president, Association of Internet Researchers

“What Google does do is simply to enable us to shift certain tasks to the network – we no longer need to rote-learn certain seldomly-used facts (the periodic table, the post code of Ballarat) if they’re only a search away, for example. That’s problematic, of course – we put an awful amount of trust in places such as Wikipedia where such information is stored, and in search engines like Google through which we retrieve it – but it doesn’t make us stupid, any more than having access to a library (or in fact, access to writing) makes us stupid. That said, I don’t know that the reverse is true, either: Google and the Net also don’t automatically make us smarter. By 2020, we will have even more access to even more information, using even more sophisticated search and retrieval tools – but how smartly we can make use of this potential depends on whether our media literacies and capacities have caught up, too.” – Axel Bruns, Associate Professor, Queensland University of Technology

“My ability to do mental arithmetic is worse than my grandfathers because I grew up in an era with pervasive personal calculators…. I am not stupid compared to my grandfather, but I believe the development of my brain has been changed by the availability of technology. The same will happen (or is happening) as a result of the Googleization of knowledge. People are becoming used to bite sized chunks of information that are compiled and sorted by an algorithm. This must be having an impact on our brains, but it is too simplistic to say that we are becoming stupid as a result of Google.” – Robert Acklund, Australian National University

“We become adept at using useful tools, and hence perfect new skills. Other skills may diminish. I agree with Carr that we may on the average become less patient, less willing to read through a long, linear text, but we may also become more adept at dealing with multiple factors…. Note that I said ‘less patient,’ which is not the same as ‘lower IQ.’ I suspect that emotional and personality changes will probably more marked than ‘intelligence’ changes.” – Larry Press , California State University, Dominguz Hills

Technology isn’t the problem here. It is people’s inherent character traits. The internet and search engines just enable people to be more of what they already are. If they are motivated to learn and shrewd, they will use new tools to explore in exciting new ways. If they are lazy or incapable of concentrating, they will find new ways to be distracted and goof off.

“The question is all about people’s choices. If we value introspection as a road to insight, if we believe that long experience with issues contributes to good judgment on those issues, if we (in short) want knowledge that search engines don’t give us, we’ll maintain our depth of thinking and Google will only enhance it. There is a trend, of course, toward instant analysis and knee-jerk responses to events that degrades a lot of writing and discussion. We can’t blame search engines for that…. What search engines do is provide more information, which we can use either to become dilettantes (Carr’s worry) or to bolster our knowledge around the edges and do fact-checking while we rely mostly on information we’ve gained in more robust ways for our core analyses. Google frees the time we used to spend pulling together the last 10% of facts we need to complete our research. I read Carr’s article when The Atlantic first published it, but I used a web search to pull it back up and review it before writing this response. Google is my friend.” – Andy Oram , editor and blogger, O’Reilly Media

“For people who are readers and who are willing to explore new sources and new arguments, we can only be made better by the kinds of searches we will be able to do. Of course, the kind of Googled future that I am concerned about is the one in which my every desire is anticipated, and my every fear avoided by my guardian Google. Even then, I might not be stupid, just not terribly interesting.” – Oscar Gandy, emeritus professor, University of Pennsylvania

“I don’t think having access to information can ever make anyone stupider. I don’t think an adult’s IQ can be influenced much either way by reading anything and I would guess that smart people will use the Internet for smart things and stupid people will use it for stupid things in the same way that smart people read literature and stupid people read crap fiction. On the whole, having easy access to more information will make society as a group smarter though.” – Sandra Kelly, market researcher, 3M Corporation

“The story of humankind is that of work substitution and human enhancement. The Neolithic revolution brought the substitution of some human physical work by animal work. The Industrial revolution brought more substitution of human physical work by machine work. The Digital revolution is implying a significant substitution of human brain work by computers and ICTs in general. Whenever a substitution has taken place, men have been able to focus on more qualitative tasks, entering a virtuous cycle: the more qualitative the tasks, the more his intelligence develops; and the more intelligent he gets, more qualitative tasks he can perform…. As obesity might be the side-effect of physical work substitution my machines, mental laziness can become the watermark of mental work substitution by computers, thus having a negative effect instead of a positive one.” – Ismael Pe ñ a-Lopez , lecturer at the Open University of Catalonia, School of Law and Political Science

“Well, of course, it depends on what one means by ‘stupid’ — I imagine that Google, and its as yet unimaginable new features and capabilities will both improve and decrease some of our human capabilities. Certainly it’s much easier to find out stuff, including historical, accurate, and true stuff, as well as entertaining, ironic, and creative stuff. It’s also making some folks lazier, less concerned about investing in the time and energy to arrive at conclusions, etc.” – Ron Rice, University of California, Santa Barbara

“Google isn’t making us stupid – but it is making many of us intellectually lazy. This has already become a big problem in university classrooms. For my undergrad majors in Communication Studies, Google may take over the hard work involved in finding good source material for written assignments. Unless pushed in the right direction, students will opt for the top 10 or 15 hits as their research strategy. And it’s the students most in need of research training who are the least likely to avail themselves of more sophisticated tools like Google Scholar. Like other major technologies, Google’s search functionality won’t push the human intellect in one predetermined direction. It will reinforce certain dispositions in the end-user: stronger intellects will use Google as a creative tool, while others will let Google do the thinking for them.” – David Ellis, York University, Toronto

It’s not Google’s fault if users create stupid queries.

“To be more precise, unthinking use of the Internet, and in particular untutored use of Google, has the ability to make us stupid, but that is not a foregone conclusion. More and more of us experience attention deficit, like Bruce Friedman in the Nicholas Carr article, but that alone does not stop us making good choices provided that the “factoids” of information are sound that we use to make out decisions. The potential for stupidity comes where we rely on Google (or Yahoo, or Bing, or any engine) to provide relevant information in response to poorly constructed queries, frequently one-word queries, and then base decisions or conclusions on those returned items.” – Peter Griffiths, former Head of Information at the Home Office within the Office of the Chief Information Officer, United Kingdom

“The problem isn’t Google; it’s what Google helps us find. For some, Google will let them find useless content that does not challenge their minds. But for others, Google will lead them to expect answers to questions, to explore the world, to see and think for themselves.” – Esther Dyson , longtime Internet expert and investor

“People are already using Google as an adjunct to their own memory. For example, I have a hunch about something, need facts to support, and Google comes through for me. Sometimes, I see I’m wrong, and I appreciate finding that out before I open my mouth.” – Craig Newmark, founder Craig’s List

“Google is a data access tool. Not all of that data is useful or correct. I suspect the amount of misleading data is increasing faster than the amount of correct data. There should also be a distinction made between data and information. Data is meaningless in the absence of an organizing context. That means that different people looking at the same data are likely to come to different conclusions. There is a big difference with what a world class artist can do with a paint brush as opposed to a monkey. In other words, the value of Google will depend on what the user brings to the game. The value of data is highly dependent on the quality of the question being asked.” – Robert Lunn, consultant, FocalPoint Analytics

The big struggle is over what kind of information Google and other search engines kick back to users. In the age of social media where users can be their own content creators it might get harder and harder to separate high-quality material from junk.

“Access to more information isn’t enough — the information needs to be correct, timely, and presented in a manner that enables the reader to learn from it. The current network is full of inaccurate, misleading, and biased information that often crowds out the valid information. People have not learned that ‘popular’ or ‘available’ information is not necessarily valid.”– Gene Spafford , Purdue University CERIAS, Association for Computing Machinery U.S. Public Policy Council

“If we take ‘Google’ to mean the complex social, economic and cultural phenomenon that is a massively interactive search and retrieval information system used by people and yet also using them to generate its data, I think Google will, at the very least, not make us smarter and probably will make us more stupid in the sense of being reliant on crude, generalised approximations of truth and information finding. Where the questions are easy, Google will therefore help; where the questions are complex, we will flounder.” – Matt Allen, former president of the Association of Internet Researchers and associate professor of internet studies at Curtin University in Australia

“The challenge is in separating that wheat from the chaff, as it always has been with any other source of mass information, which has been the case all the way back to ancient institutions like libraries. Those users (of Google, cable TV, or libraries) who can do so efficiently will beat the odds, becoming ‘smarter’ and making better choices. However, the unfortunately majority will continue to remain, as Carr says, stupid.” – Christopher Saunders, managing editor internetnews.com

“The problem with Google that is lurking just under the clean design home page is the “tragedy of the commons”: the link quality seems to go down every year. The link quality may actually not be going down but the signal to noise is getting worse as commercial schemes lead to more and more junk links.” – Glen Edens, former senior vice president and director at Sun Microsystems Laboratories, chief scientist Hewlett Packard

Literary intelligence is very much under threat.

“If one defines — or partially defines — IQ as literary intelligence, the ability to sit with a piece of textual material and analyze it for complex meaning and retain derived knowledge, then we are indeed in trouble. Literary culture is in trouble…. We are spending less time reading books, but the amount of pure information that we produce as a civilization continues to expand exponentially. That these trends are linked, that the rise of the latter is causing the decline of the former, is not impossible…. One could draw reassurance from today’s vibrant Web culture if the general surfing public, which is becoming more at home in this new medium, displayed a growing propensity for literate, critical thought. But take a careful look at the many blogs, post comments, Facebook pages, and online conversations that characterize today’s Web 2.0 environment…. This type of content generation, this method of ‘writing,’ is not only sub-literate, it may actually undermine the literary impulse…. Hours spent texting and e-mailing, according to this view, do not translate into improved writing or reading skills.” – Patrick Tucker, senior editor, The Futurist magazine

New literacies will be required to function in this world. In fact, the internet might change the very notion of what it means to be smart. Retrieval of good information will be prized. Maybe a race of “extreme Googlers” will come into being.

“The critical uncertainty here is whether people will learn and be taught the essential literacies necessary for thriving in the current infosphere: attention, participation, collaboration, crap detection, and network awareness are the ones I’m concentrating on. I have no reason to believe that people will be any less credulous, gullible, lazy, or prejudiced in ten years, and am not optimistic about the rate of change in our education systems, but it is clear to me that people are not going to be smarter without learning the ropes.” – Howard Rheingold, author of several prominent books on technology, teacher at Stanford University and University of California-Berkeley

“Google makes us simultaneously smarter and stupider. Got a question? With instant access to practically every piece of information ever known to humankind, we take for granted we’re only a quick web search away from the answer. Of course, that doesn’t mean we understand it. In the coming years we will have to continue to teach people to think critically so they can better understand the wealth of information available to them.” — Jeska Dzwigalski , Linden Lab

“We might imagine that in ten years, our definition of intelligence will look very different. By then, we might agree on “smart” as something like a ‘networked’ or ‘distributed’ intelligence where knowledge is our ability to piece together various and disparate bits of information into coherent and novel forms.” – Christine Greenhow, educational researcher, University of Minnesota and Yale Information and Society Project

“Human intellect will shift from the ability to retain knowledge towards the skills to discover the information i.e. a race of extreme Googlers (or whatever discovery tools come next). The world of information technology will be dominated by the algorithm designers and their librarian cohorts. Of course, the information they’re searching has to be right in the first place. And who decides that?” – Sam Michel, founder Chinwag, community for digital media practitioners in the United Kingdom

One new “literacy” that might help is the capacity to build and use social networks to help people solve problems.

“There’s no doubt that the internet is an extension of human intelligence, both individual and collective. But the extent to which it’s able to augment intelligence depends on how much people are able to make it conform to their needs. Being able to look up who starred in the 2nd season of the Tracey Ullman show on Wikipedia is the lowest form of intelligence augmentation; being able to build social networks and interactive software that helps you answer specific questions or enrich your intellectual life is much more powerful. This will matter even more as the internet becomes more pervasive. Already my iPhone functions as the external, silicon lobe of my brain. For it to help me become even smarter, it will need to be even more effective and flexible than it already is. What worries me is that device manufacturers and internet developers are more concerned with lock-in than they are with making people smarter. That means it will be a constant struggle for individuals to reclaim their intelligence from the networks they increasingly depend upon.” – Dylan Tweney, senior editor, Wired magazine

Nothing can be bad that delivers more information to people, more efficiently. It might be that some people lose their way in this world, but overall, societies will be substantially smarter.

“The Internet has facilitated orders of magnitude improvements in access to information. People now answer questions in a few moments that a couple of decades back they would not have bothered to ask, since getting the answer would have been impossibly difficult.” – John Pike, Director, globalsecurity.org

“Google is simply one step, albeit a major one, in the continuing continuum of how technology changes our generation and use of data, information, and knowledge that has been evolving for decades. As the data and information goes digital and new information is created, which is at an ever increasing rate, the resultant ability to evaluate, distill, coordinate, collaborate, problem solve only increases along a similar line. Where it may appear a ‘dumbing down’ has occurred on one hand, it is offset (I believe in multiples) by how we learn in new ways to learn, generate new knowledge, problem solve, and innovate.” — Mario Morino, Chairman, Venture Philanthropy Partners

Google itself and other search technologies will get better over time and that will help solve problems created by too-much-information and too-much-distraction.

“I’m optimistic that Google will get smarter by 2020 or will be replaced by a utility that is far better than Google. That tool will allow queries to trigger chains of high-quality information – much closer to knowledge than flood. Humans who are able to access these chains in high-speed, immersive ways will have more patters available to them that will aid decision-making. All of this optimism will only work out if the battle for the soul of the Internet is won by the right people – the people who believe that open, fast, networks are good for all of us.” – Susan Crawford , former member of President Obama’s National Economic Council, now on the law faculty at the University of Michigan

“If I am using Google to find an answer, it is very likely the answer I find will be on a message board in which other humans are collaboratively debating answers to questions. I will have to choose between the answer I like the best. Or it will force me to do more research to find more information. Google never breeds passivity or stupidity in me: It catalyzes me to explore further. And along the way I bump into more humans, more ideas and more answers.” – Joshua Fouts, Senior Fellow for Digital Media & Public Policy at the Center for the Study of the Presidency

The more we use the internet and search, the more dependent on it we will become.

“As the Internet gets more sophisticated it will enable a greater sense of empowerment among users. We will not be more stupid, but we will probably be more dependent upon it.” – Bernie Hogan, Oxford Internet Institute

Even in little ways, including in dinner table chitchat, Google can make people smarter.

[Family dinner conversations]

‘We know more than ever, and this makes us crazy.’

“The answer is really: both. Google has already made us smarter, able to make faster choices from more information. Children, to say nothing of adults, scientists and professionals in virtually every field, can seek and discover knowledge in ways and with scope and scale that was unfathomable before Google. Google has undoubtedly expanded our access to knowledge that can be experienced on a screen, or even processed through algorithms, or mapped. Yet Google has also made us careless too, or stupid when, for instance, Google driving directions don’t get us to the right place. It ahs confused and overwhelmed us with choices, and with sources that are not easily differentiated or verified. Perhaps it’s even alienated us from the physical world itself – from knowledge and intelligence that comes from seeing, touching, hearing, breathing and tasting life. From looking into someone’s eyes and having them look back into ours. Perhaps it’s made us impatient, or shortened our attention spans, or diminished our ability to understand long thoughts. It’s enlightened anxiety. We know more than ever, and this makes us crazy.” – Andrew Nachison, co-founder, We Media

A final thought: Maybe Google won’t make us more stupid, but it should make us more modest.

“There is and will be lots more to think about, and a lot more are thinking. No, not more stupid. Maybe more humble.” — Sheizaf Rafaeli, Center for the Study of the Information Society, University of Haifa

- Note: Previously, this sentence had incorrectly stated that the article was published in the summer of 2009. ↩

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Future of the Internet (Project)

- Online Privacy & Security

- Platforms & Services

- Privacy Rights

- Social Media

- Technology Adoption

About 1 in 4 U.S. teachers say their school went into a gun-related lockdown in the last school year

About half of americans say public k-12 education is going in the wrong direction, what public k-12 teachers want americans to know about teaching, what’s it like to be a teacher in america today, race and lgbtq issues in k-12 schools, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

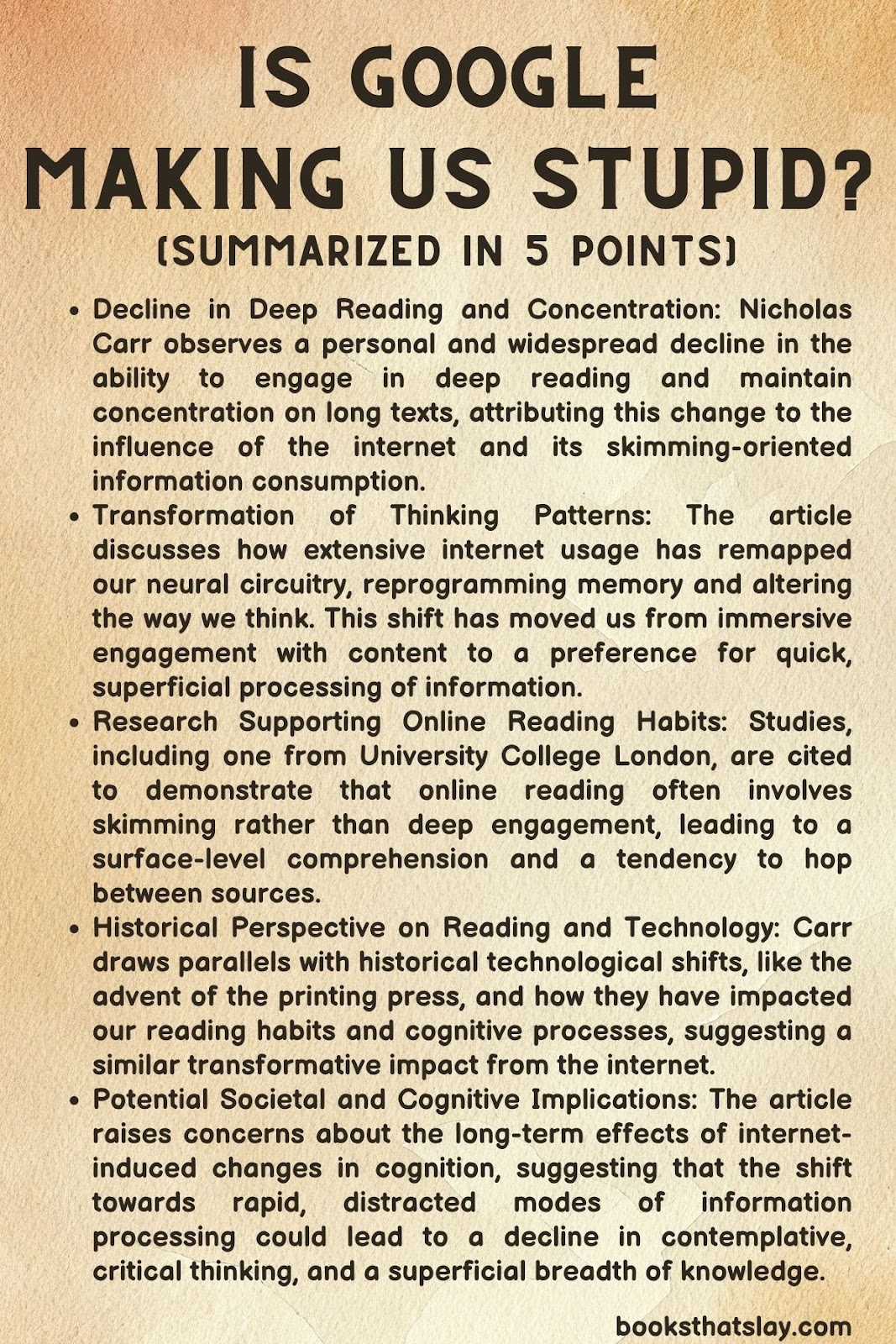

Is Google Making Us Stupid Summary, Purpose and Analysis

“Is Google Making Us Stupid?” is an article by Nicholas Carr, delving into the impacts of the internet on our cognitive abilities.

Carr explores how his own mind has changed, noting a decline in his capacity for concentration and deep reading. He attributes this to his extensive online activities, which have reshaped his thinking patterns to align more with the rapid, skimming nature of web browsing.

Full Summary

Carr isn’t alone in his experience.

He mentions friends and acquaintances, including literary types and bloggers, who share similar struggles with focusing on lengthy texts. The phenomenon isn’t just anecdotal; research backs it up.

A study from University College London found that online reading often involves skimming rather than in-depth exploration, with people hopping between sources without fully engaging with any of them.

The article dives into the history of reading and its evolution, discussing how technologies like the printing press and now the internet have changed our approach to reading and, by extension, our thinking.

Carr draws on the perspectives of experts like Maryanne Wolf, who argues that the internet promotes a more superficial form of reading, impacting our ability to think deeply and make rich mental connections.

Carr also touches upon historical figures like Nietzsche, who experienced a change in his writing style after starting to use a typewriter. This example illustrates how new technologies can subtly influence our cognitive processes.

The broader implications of this shift are significant. As we increasingly rely on the internet for information, our minds adapt to its rapid, interruptive nature, potentially diminishing our capacity for contemplation and reflection.

Carr suggests that this change might lead to a broader societal impact, where deep, critical thinking becomes less common, and we become more like “pancake people” – spread wide and thin in our knowledge and understanding.

In conclusion, Carr’s article raises important questions about the cognitive effects of the internet.

While acknowledging the immense benefits of easy access to information, he urges us to consider what might be lost in this trade-off – the depth and richness of thought that comes from deep, uninterrupted reading and contemplation.

The purpose of the article is multifaceted and centers around exploring the impact of the Internet, particularly search engines like Google, on our cognitive processes, particularly our ability to concentrate, comprehend, and engage in deep thinking.

The article serves several key functions, some of them being –

1. Raising Awareness about Cognitive Changes

Carr aims to draw attention to a subtle but profound shift in how our minds function due to prolonged exposure to the Internet. He shares personal experiences and observations to illustrate how our ability to concentrate and immerse ourselves in deep reading is diminishing.

By doing so, he encourages readers to reflect on their cognitive experiences and recognize similar patterns in their behavior.

2. Stimulating Intellectual Discourse

The article is a springboard for broader discussion about the nature of intelligence, reading, and learning in the digital age.

Carr doesn’t just present a personal dilemma but taps into a larger cultural and intellectual concern, inviting readers, educators, and scholars to ponder the implications of our growing dependency on digital technology for information processing.

3. Reviewing and Interpreting Research and Theories

Carr integrates research findings and theories from various fields, including neuroscience, psychology , and media studies, to provide a scientific basis for his arguments.

He references studies and experts to suggest that the Internet’s structure and use patterns significantly influence our neural pathways, affecting our memory, attention spans, and even the depth of our thinking.

4. Historical Contextualization

The article places the current technological shift in a historical context, comparing the Internet’s impact on our cognitive abilities to that of previous technologies, such as the clock and the printing press.

Carr uses historical analogies to show that while new technologies often bring significant benefits, they can also have unintended consequences for how we think and process information.

5. Provoking a Reevaluation of Our Relationship with Technology

Carr’s article serves as a call to critically assess our relationship with digital technology. He encourages readers to consider how their interactions with the Internet might be shaping their mental habits and to ponder if this influence is entirely beneficial.

6. Ethical and Philosophical Implications

The article also delves into the ethical and philosophical implications of allowing technology to mediate our understanding of the world.

Carr reflects on the potential loss of certain cognitive abilities and the broader impact this could have on culture, creativity, and the human experience.

7. Encouraging Mindful Engagement with Technology

Ultimately, Carr’s article is a plea for mindful and balanced engagement with technology.

While recognizing the immense benefits of the Internet, he advocates for a more conscious approach to how we use digital tools, suggesting that we should strive to preserve and cultivate our capacity for deep thought and contemplation.

Themes

1. the transformation of reading habits and cognitive processes.

At the heart of Nicholas Carr’s exploration is the profound transformation in how we read and process information in the digital age.

Carr delves into the subtle yet significant shift from deep, immersive reading of printed materials to the skimming and scanning habits fostered by the internet. This theme is not just a commentary on changing reading habits but a deeper inquiry into the cognitive consequences of such a shift.

He reflects on his own experiences, noting a decreased ability to engage in prolonged, focused reading, which once came naturally.

This change is attributed to the constant, rapid-fire consumption of information online, leading to a fragmented attention span.

Carr’s discussion extends beyond personal anecdotes, incorporating research findings that support the notion of diminishing depth in our reading and thinking patterns due to the internet’s influence.

2. The Impact of Technology on Mental Processes and Creativity

Another significant theme in Carr’s article is the broader impact of technology, specifically the internet, on our mental processes and creativity.

He raises concerns about the internet’s role in reshaping our thinking patterns, aligning them more with its non-linear, hyperlinked structure. This restructuring of thought processes is not just about how we seek and absorb information; it reaches into the realms of creativity and problem-solving.

Carr invokes historical parallels, drawing on Nietzsche’s experience with the typewriter to illustrate how new technologies can subtly but fundamentally alter our cognitive styles.

This theme is further enriched by references to various studies and experts, like Patricia Greenfield, who suggest that while certain cognitive abilities, like visual-spatial skills, are enhanced by digital media, this comes at the expense of more traditional, deeper cognitive skills such as reflective thought, critical thinking, and sustained attention.

3. The Dichotomy between Efficiency and Depth in the Digital Era

Carr navigates the complex dichotomy between the efficiency provided by the internet and the potential loss of depth in our thinking. This theme is woven throughout the article, contrasting the immediate, vast access to information against the possible erosion of our capacity for deep contemplation and critical analysis.

Carr posits that while the internet acts as a powerful tool for quick information retrieval and processing, this rapid and efficient access might be undermining our ability to engage in more profound, contemplative thought processes.

He questions whether the trade-off between the speed of information access and the richness of our intellectual life is worth it, suggesting that the convenience of the internet could be leading us to a more superficial understanding of the world around us.

This theme is crucial as it encapsulates the broader societal implications of our growing dependency on digital technologies, prompting a reflection on what we gain and what we might be inadvertently sacrificing in the digital age.

Arguments and Evidence

- Personal Anecdotes : Carr begins with a personal anecdote, a rhetorical strategy that makes his argument relatable. He confesses his own struggles with concentration and deep reading, which he attributes to his internet usage.

- Historical References : He cites historical instances (like Nietzsche’s use of a typewriter) to illustrate how new technologies can subtly influence thinking and writing styles.

- Scientific Research : Carr references various studies and experts (like Maryanne Wolf and Bruce Friedman) to support his claims about the internet’s impact on our cognitive functions.

- Philosophical and Cultural Reflections : He integrates philosophical and cultural perspectives, discussing how different technologies have historically influenced human thought and culture.

- Introduction : Carr opens with a reference to Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” as a metaphor for his argument. This draws the reader in with a familiar cultural reference.

- Development of Argument : The article unfolds systematically, beginning with personal observations, then moving to broader social implications and scientific evidence.

- Conclusion : Carr concludes by reflecting on the implications of these changes, leaving the reader with questions about the role of technology in our lives.

Strengths and Weaknesses

- Engaging Narrative : Carr’s use of personal and historical anecdotes makes the article engaging and relatable.

- Interdisciplinary Approach : He incorporates insights from neuroscience, psychology, history, and culture, providing a well-rounded argument.

- Provocative and Thought-Provoking : The article successfully provokes deeper thought about our relationship with technology.

- Subjectivity : The heavy reliance on personal anecdotes may lead to questions about the universality of his experiences.

- Potential for Technological Determinism : Some might argue that Carr leans towards a deterministic view of technology, underestimating human agency in adapting to and shaping technological uses.

Overall Impact

Carr’s article is a significant contribution to the discourse on the internet’s impact on human cognition.

It challenges readers to critically assess their interactions with digital technology and consider the broader implications for society and culture.

While it raises more questions than it answers, it serves as a catalyst for further exploration and discussion on the role of technology in shaping our minds and lives.

Sharing is Caring!

A team of Editors at Books That Slay.

Passionate | Curious | Permanent Bibliophiles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Is Google Making Us Stupid?

What the Internet is doing to our brains

“Dave, stop. Stop, will you? Stop, Dave. Will you stop, Dave?” So the supercomputer HAL pleads with the implacable astronaut Dave Bowman in a famous and weirdly poignant scene toward the end of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey . Bowman, having nearly been sent to a deep-space death by the malfunctioning machine, is calmly, coldly disconnecting the memory circuits that control its artificial “ brain. “Dave, my mind is going,” HAL says, forlornly. “I can feel it. I can feel it.”

I can feel it, too. Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory. My mind isn’t going—so far as I can tell—but it’s changing. I’m not thinking the way I used to think. I can feel it most strongly when I’m reading. Immersing myself in a book or a lengthy article used to be easy. My mind would get caught up in the narrative or the turns of the argument, and I’d spend hours strolling through long stretches of prose. That’s rarely the case anymore. Now my concentration often starts to drift after two or three pages. I get fidgety, lose the thread, begin looking for something else to do. I feel as if I’m always dragging my wayward brain back to the text. The deep reading that used to come naturally has become a struggle.

I think I know what’s going on. For more than a decade now, I’ve been spending a lot of time online, searching and surfing and sometimes adding to the great databases of the Internet. The Web has been a godsend to me as a writer. Research that once required days in the stacks or periodical rooms of libraries can now be done in minutes. A few Google searches, some quick clicks on hyperlinks, and I’ve got the telltale fact or pithy quote I was after. Even when I’m not working, I’m as likely as not to be foraging in the Web’s info-thickets—reading and writing e-mails, scanning headlines and blog posts, watching videos and listening to podcasts, or just tripping from link to link to link. (Unlike footnotes, to which they’re sometimes likened, hyperlinks don’t merely point to related works; they propel you toward them.)

For me, as for others, the Net is becoming a universal medium, the conduit for most of the information that flows through my eyes and ears and into my mind. The advantages of having immediate access to such an incredibly rich store of information are many, and they’ve been widely described and duly applauded. “The perfect recall of silicon memory,” Wired ’s Clive Thompson has written , “can be an enormous boon to thinking.” But that boon comes at a price. As the media theorist Marshall McLuhan pointed out in the 1960s, media are not just passive channels of information. They supply the stuff of thought, but they also shape the process of thought. And what the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation. My mind now expects to take in information the way the Net distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles. Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.

I’m not the only one. When I mention my troubles with reading to friends and acquaintances—literary types, most of them—many say they’re having similar experiences. The more they use the Web, the more they have to fight to stay focused on long pieces of writing. Some of the bloggers I follow have also begun mentioning the phenomenon. Scott Karp, who writes a blog about online media , recently confessed that he has stopped reading books altogether. “I was a lit major in college, and used to be [a] voracious book reader,” he wrote. “What happened?” He speculates on the answer: “What if I do all my reading on the web not so much because the way I read has changed, i.e. I’m just seeking convenience, but because the way I THINK has changed?”

Bruce Friedman, who blogs regularly about the use of computers in medicine , also has described how the Internet has altered his mental habits. “I now have almost totally lost the ability to read and absorb a longish article on the web or in print,” he wrote earlier this year. A pathologist who has long been on the faculty of the University of Michigan Medical School, Friedman elaborated on his comment in a telephone conversation with me. His thinking, he said, has taken on a “staccato” quality, reflecting the way he quickly scans short passages of text from many sources online. “I can’t read War and Peace anymore,” he admitted. “I’ve lost the ability to do that. Even a blog post of more than three or four paragraphs is too much to absorb. I skim it.”

Anecdotes alone don’t prove much. And we still await the long-term neurological and psychological experiments that will provide a definitive picture of how Internet use affects cognition. But a recently published study of online research habits, conducted by scholars from University College London, suggests that we may well be in the midst of a sea change in the way we read and think. As part of the five-year research program, the scholars examined computer logs documenting the behavior of visitors to two popular research sites, one operated by the British Library and one by a U.K. educational consortium, that provide access to journal articles, e-books, and other sources of written information. They found that people using the sites exhibited “a form of skimming activity,” hopping from one source to another and rarely returning to any source they’d already visited. They typically read no more than one or two pages of an article or book before they would “bounce” out to another site. Sometimes they’d save a long article, but there’s no evidence that they ever went back and actually read it. The authors of the study report:

It is clear that users are not reading online in the traditional sense; indeed there are signs that new forms of “reading” are emerging as users “power browse” horizontally through titles, contents pages and abstracts going for quick wins. It almost seems that they go online to avoid reading in the traditional sense.

Thanks to the ubiquity of text on the Internet, not to mention the popularity of text-messaging on cell phones, we may well be reading more today than we did in the 1970s or 1980s, when television was our medium of choice. But it’s a different kind of reading, and behind it lies a different kind of thinking—perhaps even a new sense of the self. “We are not only what we read,” says Maryanne Wolf, a developmental psychologist at Tufts University and the author of Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain . “We are how we read.” Wolf worries that the style of reading promoted by the Net, a style that puts “efficiency” and “immediacy” above all else, may be weakening our capacity for the kind of deep reading that emerged when an earlier technology, the printing press, made long and complex works of prose commonplace. When we read online, she says, we tend to become “mere decoders of information.” Our ability to interpret text, to make the rich mental connections that form when we read deeply and without distraction, remains largely disengaged.

Reading, explains Wolf, is not an instinctive skill for human beings. It’s not etched into our genes the way speech is. We have to teach our minds how to translate the symbolic characters we see into the language we understand. And the media or other technologies we use in learning and practicing the craft of reading play an important part in shaping the neural circuits inside our brains. Experiments demonstrate that readers of ideograms, such as the Chinese, develop a mental circuitry for reading that is very different from the circuitry found in those of us whose written language employs an alphabet. The variations extend across many regions of the brain, including those that govern such essential cognitive functions as memory and the interpretation of visual and auditory stimuli. We can expect as well that the circuits woven by our use of the Net will be different from those woven by our reading of books and other printed works.

Sometime in 1882, Friedrich Nietzsche bought a typewriter—a Malling-Hansen Writing Ball, to be precise. His vision was failing, and keeping his eyes focused on a page had become exhausting and painful, often bringing on crushing headaches. He had been forced to curtail his writing, and he feared that he would soon have to give it up. The typewriter rescued him, at least for a time. Once he had mastered touch-typing, he was able to write with his eyes closed, using only the tips of his fingers. Words could once again flow from his mind to the page.

But the machine had a subtler effect on his work. One of Nietzsche’s friends, a composer, noticed a change in the style of his writing. His already terse prose had become even tighter, more telegraphic. “Perhaps you will through this instrument even take to a new idiom,” the friend wrote in a letter, noting that, in his own work, his “‘thoughts’ in music and language often depend on the quality of pen and paper.”

Recommended Reading

Living with a computer.

How to Trick People Into Saving Money

The Dark Psychology of Social Networks

“You are right,” Nietzsche replied, “our writing equipment takes part in the forming of our thoughts.” Under the sway of the machine, writes the German media scholar Friedrich A. Kittler , Nietzsche’s prose “changed from arguments to aphorisms, from thoughts to puns, from rhetoric to telegram style.”

The human brain is almost infinitely malleable. People used to think that our mental meshwork, the dense connections formed among the 100 billion or so neurons inside our skulls, was largely fixed by the time we reached adulthood. But brain researchers have discovered that that’s not the case. James Olds, a professor of neuroscience who directs the Krasnow Institute for Advanced Study at George Mason University, says that even the adult mind “is very plastic.” Nerve cells routinely break old connections and form new ones. “The brain,” according to Olds, “has the ability to reprogram itself on the fly, altering the way it functions.”

As we use what the sociologist Daniel Bell has called our “intellectual technologies”—the tools that extend our mental rather than our physical capacities—we inevitably begin to take on the qualities of those technologies. The mechanical clock, which came into common use in the 14th century, provides a compelling example. In Technics and Civilization , the historian and cultural critic Lewis Mumford described how the clock “disassociated time from human events and helped create the belief in an independent world of mathematically measurable sequences.” The “abstract framework of divided time” became “the point of reference for both action and thought.”

The clock’s methodical ticking helped bring into being the scientific mind and the scientific man. But it also took something away. As the late MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum observed in his 1976 book, Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation , the conception of the world that emerged from the widespread use of timekeeping instruments “remains an impoverished version of the older one, for it rests on a rejection of those direct experiences that formed the basis for, and indeed constituted, the old reality.” In deciding when to eat, to work, to sleep, to rise, we stopped listening to our senses and started obeying the clock.

The process of adapting to new intellectual technologies is reflected in the changing metaphors we use to explain ourselves to ourselves. When the mechanical clock arrived, people began thinking of their brains as operating “like clockwork.” Today, in the age of software, we have come to think of them as operating “like computers.” But the changes, neuroscience tells us, go much deeper than metaphor. Thanks to our brain’s plasticity, the adaptation occurs also at a biological level.

The Internet promises to have particularly far-reaching effects on cognition. In a paper published in 1936 , the British mathematician Alan Turing proved that a digital computer, which at the time existed only as a theoretical machine, could be programmed to perform the function of any other information-processing device. And that’s what we’re seeing today. The Internet, an immeasurably powerful computing system, is subsuming most of our other intellectual technologies. It’s becoming our map and our clock, our printing press and our typewriter, our calculator and our telephone, and our radio and TV.

When the Net absorbs a medium, that medium is re-created in the Net’s image. It injects the medium’s content with hyperlinks, blinking ads, and other digital gewgaws, and it surrounds the content with the content of all the other media it has absorbed. A new e-mail message, for instance, may announce its arrival as we’re glancing over the latest headlines at a newspaper’s site. The result is to scatter our attention and diffuse our concentration.

The Net’s influence doesn’t end at the edges of a computer screen, either. As people’s minds become attuned to the crazy quilt of Internet media, traditional media have to adapt to the audience’s new expectations. Television programs add text crawls and pop-up ads, and magazines and newspapers shorten their articles, introduce capsule summaries, and crowd their pages with easy-to-browse info-snippets. When, in March of this year, The New York Times decided to devote the second and third pages of every edition to article abstracts , its design director, Tom Bodkin, explained that the “shortcuts” would give harried readers a quick “taste” of the day’s news, sparing them the “less efficient” method of actually turning the pages and reading the articles. Old media have little choice but to play by the new-media rules.

Never has a communications system played so many roles in our lives—or exerted such broad influence over our thoughts—as the Internet does today. Yet, for all that’s been written about the Net, there’s been little consideration of how, exactly, it’s reprogramming us. The Net’s intellectual ethic remains obscure.

About the same time that Nietzsche started using his typewriter, an earnest young man named Frederick Winslow Taylor carried a stopwatch into the Midvale Steel plant in Philadelphia and began a historic series of experiments aimed at improving the efficiency of the plant’s machinists. With the approval of Midvale’s owners, he recruited a group of factory hands, set them to work on various metalworking machines, and recorded and timed their every movement as well as the operations of the machines. By breaking down every job into a sequence of small, discrete steps and then testing different ways of performing each one, Taylor created a set of precise instructions—an “algorithm,” we might say today—for how each worker should work. Midvale’s employees grumbled about the strict new regime, claiming that it turned them into little more than automatons, but the factory’s productivity soared.

More than a hundred years after the invention of the steam engine, the Industrial Revolution had at last found its philosophy and its philosopher. Taylor’s tight industrial choreography—his “system,” as he liked to call it—was embraced by manufacturers throughout the country and, in time, around the world. Seeking maximum speed, maximum efficiency, and maximum output, factory owners used time-and-motion studies to organize their work and configure the jobs of their workers. The goal, as Taylor defined it in his celebrated 1911 treatise, The Principles of Scientific Management , was to identify and adopt, for every job, the “one best method” of work and thereby to effect “the gradual substitution of science for rule of thumb throughout the mechanic arts.” Once his system was applied to all acts of manual labor, Taylor assured his followers, it would bring about a restructuring not only of industry but of society, creating a utopia of perfect efficiency. “In the past the man has been first,” he declared; “in the future the system must be first.”

Taylor’s system is still very much with us; it remains the ethic of industrial manufacturing. And now, thanks to the growing power that computer engineers and software coders wield over our intellectual lives, Taylor’s ethic is beginning to govern the realm of the mind as well. The Internet is a machine designed for the efficient and automated collection, transmission, and manipulation of information, and its legions of programmers are intent on finding the “one best method”—the perfect algorithm—to carry out every mental movement of what we’ve come to describe as “knowledge work.”

Google’s headquarters, in Mountain View, California—the Googleplex—is the Internet’s high church, and the religion practiced inside its walls is Taylorism. Google, says its chief executive, Eric Schmidt, is “a company that’s founded around the science of measurement,” and it is striving to “systematize everything” it does. Drawing on the terabytes of behavioral data it collects through its search engine and other sites, it carries out thousands of experiments a day, according to the Harvard Business Review , and it uses the results to refine the algorithms that increasingly control how people find information and extract meaning from it. What Taylor did for the work of the hand, Google is doing for the work of the mind.

The company has declared that its mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” It seeks to develop “the perfect search engine,” which it defines as something that “understands exactly what you mean and gives you back exactly what you want.” In Google’s view, information is a kind of commodity, a utilitarian resource that can be mined and processed with industrial efficiency. The more pieces of information we can “access” and the faster we can extract their gist, the more productive we become as thinkers.

Where does it end? Sergey Brin and Larry Page, the gifted young men who founded Google while pursuing doctoral degrees in computer science at Stanford, speak frequently of their desire to turn their search engine into an artificial intelligence, a HAL-like machine that might be connected directly to our brains. “The ultimate search engine is something as smart as people—or smarter,” Page said in a speech a few years back. “For us, working on search is a way to work on artificial intelligence.” In a 2004 interview with Newsweek , Brin said, “Certainly if you had all the world’s information directly attached to your brain, or an artificial brain that was smarter than your brain, you’d be better off.” Last year, Page told a convention of scientists that Google is “really trying to build artificial intelligence and to do it on a large scale.”

Such an ambition is a natural one, even an admirable one, for a pair of math whizzes with vast quantities of cash at their disposal and a small army of computer scientists in their employ. A fundamentally scientific enterprise, Google is motivated by a desire to use technology, in Eric Schmidt’s words, “to solve problems that have never been solved before,” and artificial intelligence is the hardest problem out there. Why wouldn’t Brin and Page want to be the ones to crack it?

Still, their easy assumption that we’d all “be better off” if our brains were supplemented, or even replaced, by an artificial intelligence is unsettling. It suggests a belief that intelligence is the output of a mechanical process, a series of discrete steps that can be isolated, measured, and optimized. In Google’s world, the world we enter when we go online, there’s little place for the fuzziness of contemplation. Ambiguity is not an opening for insight but a bug to be fixed. The human brain is just an outdated computer that needs a faster processor and a bigger hard drive.

The idea that our minds should operate as high-speed data-processing machines is not only built into the workings of the Internet, it is the network’s reigning business model as well. The faster we surf across the Web—the more links we click and pages we view—the more opportunities Google and other companies gain to collect information about us and to feed us advertisements. Most of the proprietors of the commercial Internet have a financial stake in collecting the crumbs of data we leave behind as we flit from link to link—the more crumbs, the better. The last thing these companies want is to encourage leisurely reading or slow, concentrated thought. It’s in their economic interest to drive us to distraction.

Maybe I’m just a worrywart. Just as there’s a tendency to glorify technological progress, there’s a countertendency to expect the worst of every new tool or machine. In Plato’s Phaedrus , Socrates bemoaned the development of writing. He feared that, as people came to rely on the written word as a substitute for the knowledge they used to carry inside their heads, they would, in the words of one of the dialogue’s characters, “cease to exercise their memory and become forgetful.” And because they would be able to “receive a quantity of information without proper instruction,” they would “be thought very knowledgeable when they are for the most part quite ignorant.” They would be “filled with the conceit of wisdom instead of real wisdom.” Socrates wasn’t wrong—the new technology did often have the effects he feared—but he was shortsighted. He couldn’t foresee the many ways that writing and reading would serve to spread information, spur fresh ideas, and expand human knowledge (if not wisdom).

The arrival of Gutenberg’s printing press, in the 15th century, set off another round of teeth gnashing. The Italian humanist Hieronimo Squarciafico worried that the easy availability of books would lead to intellectual laziness, making men “less studious” and weakening their minds. Others argued that cheaply printed books and broadsheets would undermine religious authority, demean the work of scholars and scribes, and spread sedition and debauchery. As New York University professor Clay Shirky notes, “Most of the arguments made against the printing press were correct, even prescient.” But, again, the doomsayers were unable to imagine the myriad blessings that the printed word would deliver.

So, yes, you should be skeptical of my skepticism. Perhaps those who dismiss critics of the Internet as Luddites or nostalgists will be proved correct, and from our hyperactive, data-stoked minds will spring a golden age of intellectual discovery and universal wisdom. Then again, the Net isn’t the alphabet, and although it may replace the printing press, it produces something altogether different. The kind of deep reading that a sequence of printed pages promotes is valuable not just for the knowledge we acquire from the author’s words but for the intellectual vibrations those words set off within our own minds. In the quiet spaces opened up by the sustained, undistracted reading of a book, or by any other act of contemplation, for that matter, we make our own associations, draw our own inferences and analogies, foster our own ideas. Deep reading , as Maryanne Wolf argues, is indistinguishable from deep thinking.

If we lose those quiet spaces, or fill them up with “content,” we will sacrifice something important not only in our selves but in our culture. In a recent essay , the playwright Richard Foreman eloquently described what’s at stake:

I come from a tradition of Western culture, in which the ideal (my ideal) was the complex, dense and “cathedral-like” structure of the highly educated and articulate personality—a man or woman who carried inside themselves a personally constructed and unique version of the entire heritage of the West. [But now] I see within us all (myself included) the replacement of complex inner density with a new kind of self—evolving under the pressure of information overload and the technology of the “instantly available.”

As we are drained of our “inner repertory of dense cultural inheritance,” Foreman concluded, we risk turning into “‘pancake people’—spread wide and thin as we connect with that vast network of information accessed by the mere touch of a button.”

I’m haunted by that scene in 2001 . What makes it so poignant, and so weird, is the computer’s emotional response to the disassembly of its mind: its despair as one circuit after another goes dark, its childlike pleading with the astronaut—“I can feel it. I can feel it. I’m afraid”—and its final reversion to what can only be called a state of innocence. HAL’s outpouring of feeling contrasts with the emotionlessness that characterizes the human figures in the film, who go about their business with an almost robotic efficiency. Their thoughts and actions feel scripted, as if they’re following the steps of an algorithm. In the world of 2001 , people have become so machinelike that the most human character turns out to be a machine. That’s the essence of Kubrick’s dark prophecy: as we come to rely on computers to mediate our understanding of the world, it is our own intelligence that flattens into artificial intelligence.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic .

Is Google Making Us Stupid?

24 pages • 48 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “is google making us stupid”.

The essay “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” was written by Nicholas Carr . It was originally published in The Atlantic ’s July/August 2008 issue. The essay stirred much debate, and in 2010, Carr published an extended version of the essay in book form, entitled The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains.

The essay begins and ends with an allusion to Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the initial allusion, Carr summarizes the moment toward the end of the film in which “the supercomputer HAL pleads with the implacable astronaut Dave Bowman in a famous and weirdly poignant scene [...] Bowman, having nearly been sent to a deep-space death by the malfunctioning machine, is calmly, coldly disconnecting the memory circuits that control its artificial ‘brain.’ ‘Dave, my mind is going,’ HAL says, forlornly. ‘I can feel it. I can feel it.’” (1). Carr uses this allusion to assert that he, like HAL, has had a growing feeling that “someone, or something, has been tinkering with [his] brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory” (2). He feels that his brain has changed the way it processes information and thinks. He finds it increasingly more difficult to read deeply and with subtlety, as he loses his concentration and gets distracted and restless while reading. He attributes this change to the increase in his use of the Internet.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,450+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,900+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Carr states that he’s not alone in this as the Internet quickly becomes a “universal medium” (4). While he concedes that the Internet has provided the gift of “immediate access to such an incredibly rich store of information,” he also cites the media theorist Marshal McLuhan’s more complicated observation: “[M]edia are not just passive channels of information. They supply the stuff of thought, but they also shape the process of thought” (4). Carr asserts that “what the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation” (4). He then offers that many of his literarily-inclined friends are also observing a similar phenomenon in their own lives.

Carr points out that these anecdotes do not offer empirical proof of anything, and scientific experiments on “the long-term neurological and psychological” effects of the Internet have not yet been completed (7). However, he cites a recent study published by the University College of London that “suggests that we may well be in the midst of a sea change in the way we read and think” (7). The college’s five-year study observed “computer logs documenting the behavior of visitors to two popular research sites, one operated by the British Library and one by a U.K. educational consortium, that provide access to journal articles, e-books, and other sources of written information: “They found that people using the sites exhibited ‘a form of skimming activity,’ hopping from one source to another and rarely returning to any source they’d already visited” (7). The authors of the study ultimately concluded that readers are not reading Internet materials the way that they would read materials in more traditional media—and that the Internet is creating a new paradigm of reading, “as users ‘power browse’ horizontally through titles, contents pages and abstracts going for quick wins” (7).

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

Carr observes that the proliferation of text on both the Internet and via text messaging has likely increased the amount that people read: “But it’s a different kind of reading, and behind it lies a different kind of thinking—perhaps even a new sense of the self,” he says (8). He then cites Maryanne Wolf , the developmental psychologist at Tufts University who wrote the book Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. He writes, “Wolf worries that the style of reading promoted by the Net, a style that puts ‘efficiency’ and ‘immediacy’ above all else, may be weakening our capacity for the kind of deep reading that emerged when an earlier technology, the printing press , made long and complex works of prose commonplace” (8).

Carr then paraphrases some of Wolf’s ideas. He highlights her assertion that reading is not an instinctual human trait: “We have to teach our minds how to translate the symbolic characters we see into the language we understand. And the media or other technologies we use in learning and practicing the craft of reading play an important part in shaping the neural circuits inside our brains” (9). He therefore concludes that the neural circuits created by human use of the Internet will inevitably differ from those created in previous eras when books and other printed media were the norm. He also offers an anecdote that supports this point: Friedrich Nietzsche switched from pen and paper to a typewriter for composing his writing in 1882. Nietzsche’s friend soon noticed that the man’s writing took on a different quality as a result—becoming “tighter” and “telegraphic” (11).

Carr reminds his reader of the plasticity of the human brain, asserting that even the adult human brain “routinely [breaks] old connections and [forms] new ones” (13). Carr then defines “intellectual technologies” as “tools that extend our mental rather than our physical capacities” (14). He says that “we inevitably begin to take on the qualities of those technologies” (14). He uses the invention of the clock to prove this point, citing the cultural critic Lewis Mumford to assert that the ubiquity of the clock “disassociated time from human events and helped create the belief in an independent world of mathematically measurable sequences” (14). Carr asserts that this phenomena helped bring “the scientific mind and the scientific man” into being—but that it also took something away: “In deciding when to eat, to work, to sleep, to rise, we stopped listening to our senses and started obeying the clock” (15).

Carr asserts that this change extends beyond mere human action and into human biology and cognition. He cites the 1936 writings of Alan Turing, which predicted that the tremendous computing power of the digital computers would lead to their usurpation of preexisting forms of technology. Carr sees this happening as the Internet becomes “our map and clock, our printing press and our typewriter, our calculator and our telephone, and our radio and TV” (17). Carr observes that “when the Net absorbs a medium, that medium is re-created in the Net’s image” (18). He cites The New York Times ’ decision to “devote the second and third pages of every edition to article abstracts” to provide print readers with a similar experience to Internet readers as an example of this phenomenon (17). He then asserts that no other form of media has had as powerful an influence over human thought than the Internet, and that we have not spent enough time poring over “how, exactly, [the Internet] is reprogramming us” (20). He concludes that “[t]he Net’s intellectual ethic remains obscure” (20).

Carr then informs us that, around the same time Nietzsche switched to a typewriter, a man named Frederick Winslow Taylor invented a regimented program that separated every element of steel plant machinists’ jobs into “a sequence of small discrete steps” (21). Taylor then tested different methods of completing each step to develop “a set of precise instructions—an ‘algorithm,’ we might say today—for how each worker should work” (21). This caused a sizeable increase in productivity—although many machinists felt that the system transformed them into mere robots. However, Taylor’s system was quickly adopted by manufacturers domestically and internationally: “Taylor’s system is still very much with us; it remains the ethic of industrial manufacturing. And now, thanks to the growing power that computer engineers and software coders wield over our intellectual lives, Taylor’s ethic is beginning to govern the realm of the mind as well,” Carr asserts (23).

Carr uses Google’s mandate to “systematize everything,” as well as the company CEOs’ stated desire to perfect its search engine to eventually perfect artificial intelligence as proof of this (24). Carr writes, “[Google’s] easy assumption that we’d all ‘be better off’ if our brains were supplemented, or even replaced, by an artificial intelligence is unsettling. It suggests a belief that intelligence is the output of a mechanical process, a series of discrete steps that can be isolated, measured, and optimized” (28). Carr also points out that this regimentation of the human mind “is the [Internet’s] reigning business model as well. The faster we surf across the Web—the more links we click and pages we view—the more opportunities Google and other companies gain to collect information about us and to feed us advertisements” (29). In this atmosphere , it hurts the bottom line of such advertisers to promote the slow, considered reading and thinking pace of previous eras.

Carr then admits that he may be overly anxious in his assertions. He concedes that every introduction of a major new technology was attended to by naysayers. He states that it’s perfectly possible that the utopian prognostications and potential of the Internet could happen. However, he cites Wolf’s argument that “deep reading […] is indistinguishable from deep thinking” to shore up his own credibility (32): “If we lose those quiet spaces, or fill them up with ‘content,’ we will sacrifice something important not only in our selves but in our culture,” Carr posits (33). For Carr, this process is, in the words of the playwright Richard Foreman, “the replacement of complex inner density with a new kind of self—evolving under the pressure of information overload and the technology of the ‘instantly available’” (33).