Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

Theoretical Framework Example for a Thesis or Dissertation

Published on October 14, 2015 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Tegan George.

Your theoretical framework defines the key concepts in your research, suggests relationships between them, and discusses relevant theories based on your literature review .

A strong theoretical framework gives your research direction. It allows you to convincingly interpret, explain, and generalize from your findings and show the relevance of your thesis or dissertation topic in your field.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Sample problem statement and research questions, sample theoretical framework, your theoretical framework, other interesting articles.

Your theoretical framework is based on:

- Your problem statement

- Your research questions

- Your literature review

A new boutique downtown is struggling with the fact that many of their online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases. This is a big issue for the otherwise fast-growing store.Management wants to increase customer loyalty. They believe that improved customer satisfaction will play a major role in achieving their goal of increased return customers.

To investigate this problem, you have zeroed in on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

- Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

- Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

- Research question : How can the satisfaction of the boutique’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

The concepts of “customer loyalty” and “customer satisfaction” are clearly central to this study, along with their relationship to the likelihood that a customer will return. Your theoretical framework should define these concepts and discuss theories about the relationship between these variables.

Some sub-questions could include:

- What is the relationship between customer loyalty and customer satisfaction?

- How satisfied and loyal are the boutique’s online customers currently?

- What factors affect the satisfaction and loyalty of the boutique’s online customers?

As the concepts of “loyalty” and “customer satisfaction” play a major role in the investigation and will later be measured, they are essential concepts to define within your theoretical framework .

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Below is a simplified example showing how you can describe and compare theories in your thesis or dissertation . In this example, we focus on the concept of customer satisfaction introduced above.

Customer satisfaction

Thomassen (2003, p. 69) defines customer satisfaction as “the perception of the customer as a result of consciously or unconsciously comparing their experiences with their expectations.” Kotler & Keller (2008, p. 80) build on this definition, stating that customer satisfaction is determined by “the degree to which someone is happy or disappointed with the observed performance of a product in relation to his or her expectations.”

Performance that is below expectations leads to a dissatisfied customer, while performance that satisfies expectations produces satisfied customers (Kotler & Keller, 2003, p. 80).

The definition of Zeithaml and Bitner (2003, p. 86) is slightly different from that of Thomassen. They posit that “satisfaction is the consumer fulfillment response. It is a judgement that a product or service feature, or the product of service itself, provides a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment.” Zeithaml and Bitner’s emphasis is thus on obtaining a certain satisfaction in relation to purchasing.

Thomassen’s definition is the most relevant to the aims of this study, given the emphasis it places on unconscious perception. Although Zeithaml and Bitner, like Thomassen, say that customer satisfaction is a reaction to the experience gained, there is no distinction between conscious and unconscious comparisons in their definition.

The boutique claims in its mission statement that it wants to sell not only a product, but also a feeling. As a result, unconscious comparison will play an important role in the satisfaction of its customers. Thomassen’s definition is therefore more relevant.

Thomassen’s Customer Satisfaction Model

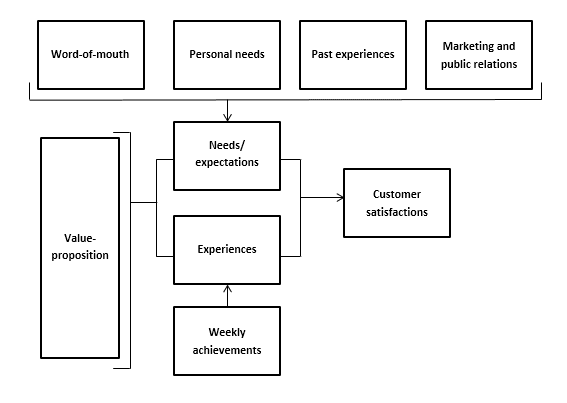

According to Thomassen, both the so-called “value proposition” and other influences have an impact on final customer satisfaction. In his satisfaction model (Fig. 1), Thomassen shows that word-of-mouth, personal needs, past experiences, and marketing and public relations determine customers’ needs and expectations.

These factors are compared to their experiences, with the interplay between expectations and experiences determining a customer’s satisfaction level. Thomassen’s model is important for this study as it allows us to determine both the extent to which the boutique’s customers are satisfied, as well as where improvements can be made.

Figure 1 Customer satisfaction creation

Of course, you could analyze the concepts more thoroughly and compare additional definitions to each other. You could also discuss the theories and ideas of key authors in greater detail and provide several models to illustrate different concepts.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Vinz, S. (2023, July 18). Theoretical Framework Example for a Thesis or Dissertation. Scribbr. Retrieved March 28, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/theoretical-framework-example/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, what is your plagiarism score.

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

- Editing Services

- Academic Editing Services

- Admissions Editing Services

- Admissions Essay Editing Services

- AI Content Editing Services

- APA Style Editing Services

- Application Essay Editing Services

- Book Editing Services

- Business Editing Services

- Capstone Paper Editing Services

- Children's Book Editing Services

- College Application Editing Services

- College Essay Editing Services

- Copy Editing Services

- Developmental Editing Services

- Dissertation Editing Services

- eBook Editing Services

- English Editing Services

- Horror Story Editing Services

- Legal Editing Services

- Line Editing Services

- Manuscript Editing Services

- MLA Style Editing Services

- Novel Editing Services

- Paper Editing Services

- Personal Statement Editing Services

- Research Paper Editing Services

- Résumé Editing Services

- Scientific Editing Services

- Short Story Editing Services

- Statement of Purpose Editing Services

- Substantive Editing Services

- Thesis Editing Services

Proofreading

- Proofreading Services

- Admissions Essay Proofreading Services

- Children's Book Proofreading Services

- Legal Proofreading Services

- Novel Proofreading Services

- Personal Statement Proofreading Services

- Research Proposal Proofreading Services

- Statement of Purpose Proofreading Services

Translation

- Translation Services

Graphic Design

- Graphic Design Services

- Dungeons & Dragons Design Services

- Sticker Design Services

- Writing Services

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

6 Steps to Mastering the Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation

As the pivotal section of your dissertation, the theoretical framework will be the lens through which your readers should evaluate your research. It's also a necessary part of your writing and research processes from which every written section will be built.

In their journal article titled Understanding, selecting, and integrating a theoretical framework in dissertation research: Creating the blueprint for your "house" , authors Cynthia Grant and Azadeh Osanloo write:

The theoretical framework is one of the most important aspects in the research process, yet is often misunderstood by doctoral candidates as they prepare their dissertation research study. The importance of theory-driven thinking and acting is emphasized in relation to the selection of a topic, the development of research questions, the conceptualization of the literature review, the design approach, and the analysis plan for the dissertation study. Using a metaphor of the "blueprint" of a house, this article explains the application of a theoretical framework in a dissertation. Administrative Issues Journal

They continue in their paper to discuss how architects and contractors understand that prior to building a house, there must be a blueprint created. This blueprint will then serve as a guide for everyone involved in the construction of the home, including those building the foundation, installing the plumbing and electrical systems, etc. They then state, We believe the blueprint is an appropriate analogy of the theoretical framework of the dissertation.

As with drawing and creating any blueprint, it is often the most difficult part of the building process. Many potential conflicts must be considered and mitigated, and much thought must be put into how the foundation will support the rest of the home. Without proper consideration on the front end, the entire structure could be at risk.

With this in mind, I'm going to discuss six steps to mastering the theoretical framework section—the "blueprint" for your dissertation. If you follow these steps and complete the checklist included, your blueprint is guaranteed to be a solid one.

Complete your review of literature first

In order to identify the scope of your theoretical framework, you'll need to address research that has already been completed by others, as well as gaps in the research. Understanding this, it's clear why you'll need to complete your review of literature before you can adequately write a theoretical framework for your dissertation or thesis.

Simply put, before conducting any extensive research on a topic or hypothesis, you need to understand where the gaps are and how they can be filled. As will be mentioned in a later step, it's important to note within your theoretical framework if you have closed any gaps in the literature through your research. It's also important to know the research that has laid a foundation for the current knowledge, including any theories, assumptions, or studies that have been done that you can draw on for your own. Without performing this necessary step, you're likely to produce research that is redundant, and therefore not likely to be published.

Understand the purpose of a theoretical framework

When you present a research problem, an important step in doing so is to provide context and background to that specific problem. This allows your reader to understand both the scope and the purpose of your research, while giving you a direction in your writing. Just as a blueprint for a home needs to provide needed context to all of the builders and professionals involved in the building process, so does the theoretical framework of your dissertation.

So, in building your theoretical framework, there are several details that need to be considered and explained, including:

- The definition of any concepts or theories you're building on or exploring (this is especially important if it is a theory that is taken from another discipline or is relatively new).

- The context in which this concept has been explored in the past.

- The important literature that has already been published on the concept or theory, including citations.

- The context in which you plan to explore the concept or theory. You can briefly mention your intended methods used, along with methods that have been used in the past—but keep in mind that there will be a separate section of your dissertation to present these in detail.

- Any gaps that you hope to fill in the research

- Any limitations encountered by past researchers and any that you encountered in your own exploration of the topic.

- Basically, your theoretical framework helps to give your reader a general understanding of the research problem, how it has already been explored, and where your research falls in the scope of it. In such, be sure to keep it written in present tense, since it is research that is presently being done. When you refer to past research by others, you can do so in past tense, but anything related to your own research should be written in the present.

Use your theoretical framework to justify your research

In your literature review, you'll focus on finding research that has been conducted that is pertinent to your own study. This could be literature that establishes theories connected with your research, or provides pertinent analytic models. You will then mention these theories or models in your own theoretical framework and justify why they are the basis of—or relevant to—your research.

Basically, think of your theoretical framework as a quick, powerful way to justify to your reader why this research is important. If you are expanding upon past research by other scholars, your theoretical framework should mention the foundation they've laid and why it is important to build on that, or how it needs to be applied to a more modern concept. If there are gaps in the research on certain topics or theories, and your research fills these gaps, mention that in your theoretical framework, as well. It is your opportunity to justify the work you've done in a scientific context—both to your dissertation committee and to any publications interested in publishing your work.

Keep it within three to five pages

While there are usually no hard and fast rules related to the length of your theoretical framework, it is most common to keep it within three to five pages. This length should be enough to provide all of the relevant information to your reader without going into depth about the theories or assumptions mentioned. If you find yourself needing many more pages to write your theoretical framework, it is likely that you've failed to provide a succinct explanation for a theory, concept, or past study. Remember—you'll have ample opportunity throughout the course of writing your dissertation to expand and expound on these concepts, past studies, methods, and hypotheses. Your theoretical framework is not the place for these details.

If you've written an abstract, consider your theoretical framework to be somewhat of an extended abstract. It should offer a glimpse of the entirety of your research without going into a detailed explanation of the methods or background of it. In many cases, chiseling the theoretical framework down to the three to five-page length is a process of determining whether detail is needed in establishing understanding for your reader.

Use models and other graphics

Since your theoretical framework should clarify complicated theories or assumptions related to your research, it's often a good idea to include models and other helpful graphics to achieve this aim. If space is an issue, most formats allow you to include these illustrations or models in the appendix of your paper and refer to them within the main text.

Use a checklist after completing your first draft

You should consider the following questions as you draft your theoretical framework and check them off as a checklist after completing your first draft:

- Have the main theories and models related to your research been presented and briefly explained? In other words, does it offer an explicit statement of assumptions and/or theories that allows the reader to make a critical evaluation of them?

- Have you correctly cited the main scientific articles on the subject?

- Does it tell the reader about current knowledge related to the assumptions/theories and any gaps in that knowledge?

- Does it offer information related to notable connections between concepts?

- Does it include a relevant theory that forms the basis of your hypotheses and methods?

- Does it answer the question of "why" your research is valid and important? In other words, does it provide scientific justification for your research?

- If your research fills a gap in the literature, does your theoretical framework state this explicitly?

- Does it include the constructs and variables (both independent and dependent) that are relevant to your study?

- Does it state assumptions and propositions that are relevant to your research (along with the guiding theories related to these)?

- Does it "frame" your entire research, giving it direction and a backbone to support your hypotheses?

- Are your research questions answered?

- Is it logical?

- Is it free of grammar, punctuation, spelling, and syntax errors?

A final note

In conclusion, I would like to leave you with a quote from Grant and Osanloo:

The importance of utilizing a theoretical framework in a dissertation study cannot be stressed enough. The theoretical framework is the foundation from which all knowledge is constructed (metaphorically and literally) for a research study. It serves as the structure and support for the rationale for the study, the problem statement, the purpose, the significance, and the research questions. The theoretical framework provides a grounding base, or an anchor, for the literature review, and most importantly, the methods and analysis. Administrative Issues Journal

Related Posts

How to Write an Effective Thesis Discussion

201 Online Research Databases and Search Engines

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

- How it works

Theoretical Framework for Dissertation – What and How

Published by Anastasia Lois at August 13th, 2021 , Revised On August 22, 2023

The theoretical framework is one of the most infamous aspects of a dissertation , but it provides a strong scientific research base. You are likely to produce a first-class dissertation if the theoretical framework is appropriate and well-thought-out.

But what is a theoretical framework? And how do you develop a theoretical framework for your dissertation?

Content for Theoretical Framework

Your theoretical framework of a dissertation should incorporate existing theories that are relevant to your study. It will also include defining the terms mentioned in the hypothesis , research questions , and problem statement . All these concepts should be clearly identified as the first step.

Theoretical Framework Goals

- You will need to identify the ideas and theories used for your chosen subject topic once you have determined the problem statement and research questions .

- You can frame your study by presenting the theoretical framework, reflecting that you have enough knowledge about your topic, relevant models, and theories.

- The theories you choose to investigate will provide direction to your research, and you can continue to make informed choices at different stages of the dissertation writing process .

- The theoretical framework bases are the scientific theories that justify your research; therefore, you must use them appropriately for referencing your investigation.

1. Select Key Concepts Sample problem statement and research questions: According to the company X report, many customers do not return after an online purchase. The company director wants to improve customer satisfaction and loyalty to achieve the long-term goal of the company. To investigate this issue, the researcher can base their research around the following problem statement, objective, and research questions: Problem: Many customers do not return after an online purchase. Objective: To improve customer satisfaction and thereby achieve long-term goals. Research question: How can online customers’ loyalty increase by increasing customer satisfaction? Sub-Questions: 1. How can you relate customer satisfaction with customer loyalty? 2. How are the online customers of company X loyal and satisfied at present? 3. What are the factors affecting online customers’ loyalty and satisfaction? The satisfaction and loyalty concepts are critical to this research; therefore, will be determined as part of this study. These are the key terms that will have to be defined in the theoretical framework for the dissertation.

2. Define and Evaluate Relevant Concepts, Theories, and Models

You will be required to review existing relevant literature to determine how other researchers have defined the key terms in the past. The definitions proposed by different scholars can then be compared critically and analytically. The last step is to choose the best concepts and their definitions matching your case.

It is also necessary to identify the relationships between the terms. Whether you are applying or not applying the existing concepts and models in your study, you will need to present your arguments and justify your choices.

3. Adding Value to the Existing Knowledge

In addition to analyzing concepts and theories proposed by other theorists, you might also want to demonstrate how your own research will contribute to the existing knowledge. Here are some questions for you to consider in this regard;

- Are you going to contribute new evidence through primary research or testing an existing theory?

- Will you understand and interpret data with the help of a theory?

- Do you wish to challenge, critique, or evaluate an existing theory?

- Is there a new exclusive method through which you will combine different theories proposed by other scholars?

Types of Research Questions you can Answer

The descriptive research questions only use the theoretical framework because their answer requires literature research. For instance, ‘how can you relate customer satisfaction with customer loyalty?’ A single theory can answer this question sufficiently.

The sub-question, ‘How the online customers of company X are loyal and satisfied at present?’ cannot be answered theoretically because it requires qualitative and quantitative research data.

Theoretical Framework Structure

There is no fixed pattern to structure the theoretical framework for the dissertation . However, you can create a logical structure by drawing on your hypothesis/research question and defining important terms.

For instance, write a paragraph containing key terms, hypotheses, or research questions and explain the relevant models and theories.

Also See: Organizing Academic Research Papers: Theoretical Framework

Length of Theoretical Framework of Dissertation

The length of the theoretical framework is usually three to five pages. You can also include the graphical framework to give your readers a clear insight into your theoretical framework. For instance, below is the graphical figure of an example theoretical framework for classroom management.

Sample Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation

Here is a theoretical framework example to provide you with a sense of the essential parts of the dissertation.

How can ResearchProspect Help?

ResearchProspect is a UK-registered firm that provides academic support to students around the world.

We specialize in completing design projects, literature reviews , essays , reports , coursework , exam notes , statistical analysis , primary and empirical research, dissertations , case studies, academic posters , and much more.

Getting help from our expert academics is quick and simple. All you have to do is complete our online order form and get your paper delivered to your email address well before your due deadline.

Looking for dissertation help?

Researchprospect to the rescue then.

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with dissertations across a variety of disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

Frequently Asked Questions

How do i choose a theoretical framework for my dissertation.

To choose a theoretical framework for your dissertation:

- Define research objectives.

- Identify relevant disciplines.

- Review existing theories.

- Select one aligning with your topic.

- Consider its applicability.

- Justify your choice based on relevance and depth.

You May Also Like

When writing your dissertation, an abstract serves as a deal maker or breaker. It can either motivate your readers to continue reading or discourage them.

Appendices or Appendixes are used to provide additional date related to your dissertation research project. Here we explain what is appendix in dissertation

The list of figures and tables in dissertation help the readers find tables and figures of their interest without looking through the whole dissertation.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Theoretical Framework

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Theories are formulated to explain, predict, and understand phenomena and, in many cases, to challenge and extend existing knowledge within the limits of critical bounded assumptions or predictions of behavior. The theoretical framework is the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. The theoretical framework encompasses not just the theory, but the narrative explanation about how the researcher engages in using the theory and its underlying assumptions to investigate the research problem. It is the structure of your paper that summarizes concepts, ideas, and theories derived from prior research studies and which was synthesized in order to form a conceptual basis for your analysis and interpretation of meaning found within your research.

Abend, Gabriel. "The Meaning of Theory." Sociological Theory 26 (June 2008): 173–199; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (December 2018): 44-53; Swanson, Richard A. Theory Building in Applied Disciplines . San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers 2013; Varpio, Lara, Elise Paradis, Sebastian Uijtdehaage, and Meredith Young. "The Distinctions between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework." Academic Medicine 95 (July 2020): 989-994.

Importance of Theory and a Theoretical Framework

Theories can be unfamiliar to the beginning researcher because they are rarely applied in high school social studies curriculum and, as a result, can come across as unfamiliar and imprecise when first introduced as part of a writing assignment. However, in their most simplified form, a theory is simply a set of assumptions or predictions about something you think will happen based on existing evidence and that can be tested to see if those outcomes turn out to be true. Of course, it is slightly more deliberate than that, therefore, summarized from Kivunja (2018, p. 46), here are the essential characteristics of a theory.

- It is logical and coherent

- It has clear definitions of terms or variables, and has boundary conditions [i.e., it is not an open-ended statement]

- It has a domain where it applies

- It has clearly described relationships among variables

- It describes, explains, and makes specific predictions

- It comprises of concepts, themes, principles, and constructs

- It must have been based on empirical data [i.e., it is not a guess]

- It must have made claims that are subject to testing, been tested and verified

- It must be clear and concise

- Its assertions or predictions must be different and better than those in existing theories

- Its predictions must be general enough to be applicable to and understood within multiple contexts

- Its assertions or predictions are relevant, and if applied as predicted, will result in the predicted outcome

- The assertions and predictions are not immutable, but subject to revision and improvement as researchers use the theory to make sense of phenomena

- Its concepts and principles explain what is going on and why

- Its concepts and principles are substantive enough to enable us to predict a future

Given these characteristics, a theory can best be understood as the foundation from which you investigate assumptions or predictions derived from previous studies about the research problem, but in a way that leads to new knowledge and understanding as well as, in some cases, discovering how to improve the relevance of the theory itself or to argue that the theory is outdated and a new theory needs to be formulated based on new evidence.

A theoretical framework consists of concepts and, together with their definitions and reference to relevant scholarly literature, existing theory that is used for your particular study. The theoretical framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are relevant to the topic of your research paper and that relate to the broader areas of knowledge being considered.

The theoretical framework is most often not something readily found within the literature . You must review course readings and pertinent research studies for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power.

The theoretical framework strengthens the study in the following ways :

- An explicit statement of theoretical assumptions permits the reader to evaluate them critically.

- The theoretical framework connects the researcher to existing knowledge. Guided by a relevant theory, you are given a basis for your hypotheses and choice of research methods.

- Articulating the theoretical assumptions of a research study forces you to address questions of why and how. It permits you to intellectually transition from simply describing a phenomenon you have observed to generalizing about various aspects of that phenomenon.

- Having a theory helps you identify the limits to those generalizations. A theoretical framework specifies which key variables influence a phenomenon of interest and highlights the need to examine how those key variables might differ and under what circumstances.

- The theoretical framework adds context around the theory itself based on how scholars had previously tested the theory in relation their overall research design [i.e., purpose of the study, methods of collecting data or information, methods of analysis, the time frame in which information is collected, study setting, and the methodological strategy used to conduct the research].

By virtue of its applicative nature, good theory in the social sciences is of value precisely because it fulfills one primary purpose: to explain the meaning, nature, and challenges associated with a phenomenon, often experienced but unexplained in the world in which we live, so that we may use that knowledge and understanding to act in more informed and effective ways.

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Corvellec, Hervé, ed. What is Theory?: Answers from the Social and Cultural Sciences . Stockholm: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2013; Asher, Herbert B. Theory-Building and Data Analysis in the Social Sciences . Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1984; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (2018): 44-53; Omodan, Bunmi Isaiah. "A Model for Selecting Theoretical Framework through Epistemology of Research Paradigms." African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies 4 (2022): 275-285; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Jarvis, Peter. The Practitioner-Researcher. Developing Theory from Practice . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

Strategies for Developing the Theoretical Framework

I. Developing the Framework

Here are some strategies to develop of an effective theoretical framework:

- Examine your thesis title and research problem . The research problem anchors your entire study and forms the basis from which you construct your theoretical framework.

- Brainstorm about what you consider to be the key variables in your research . Answer the question, "What factors contribute to the presumed effect?"

- Review related literature to find how scholars have addressed your research problem. Identify the assumptions from which the author(s) addressed the problem.

- List the constructs and variables that might be relevant to your study. Group these variables into independent and dependent categories.

- Review key social science theories that are introduced to you in your course readings and choose the theory that can best explain the relationships between the key variables in your study [note the Writing Tip on this page].

- Discuss the assumptions or propositions of this theory and point out their relevance to your research.

A theoretical framework is used to limit the scope of the relevant data by focusing on specific variables and defining the specific viewpoint [framework] that the researcher will take in analyzing and interpreting the data to be gathered. It also facilitates the understanding of concepts and variables according to given definitions and builds new knowledge by validating or challenging theoretical assumptions.

II. Purpose

Think of theories as the conceptual basis for understanding, analyzing, and designing ways to investigate relationships within social systems. To that end, the following roles served by a theory can help guide the development of your framework.

- Means by which new research data can be interpreted and coded for future use,

- Response to new problems that have no previously identified solutions strategy,

- Means for identifying and defining research problems,

- Means for prescribing or evaluating solutions to research problems,

- Ways of discerning certain facts among the accumulated knowledge that are important and which facts are not,

- Means of giving old data new interpretations and new meaning,

- Means by which to identify important new issues and prescribe the most critical research questions that need to be answered to maximize understanding of the issue,

- Means of providing members of a professional discipline with a common language and a frame of reference for defining the boundaries of their profession, and

- Means to guide and inform research so that it can, in turn, guide research efforts and improve professional practice.

Adapted from: Torraco, R. J. “Theory-Building Research Methods.” In Swanson R. A. and E. F. Holton III , editors. Human Resource Development Handbook: Linking Research and Practice . (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1997): pp. 114-137; Jacard, James and Jacob Jacoby. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Guilford, 2010; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Sutton, Robert I. and Barry M. Staw. “What Theory is Not.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (September 1995): 371-384.

Structure and Writing Style

The theoretical framework may be rooted in a specific theory , in which case, your work is expected to test the validity of that existing theory in relation to specific events, issues, or phenomena. Many social science research papers fit into this rubric. For example, Peripheral Realism Theory, which categorizes perceived differences among nation-states as those that give orders, those that obey, and those that rebel, could be used as a means for understanding conflicted relationships among countries in Africa. A test of this theory could be the following: Does Peripheral Realism Theory help explain intra-state actions, such as, the disputed split between southern and northern Sudan that led to the creation of two nations?

However, you may not always be asked by your professor to test a specific theory in your paper, but to develop your own framework from which your analysis of the research problem is derived . Based upon the above example, it is perhaps easiest to understand the nature and function of a theoretical framework if it is viewed as an answer to two basic questions:

- What is the research problem/question? [e.g., "How should the individual and the state relate during periods of conflict?"]

- Why is your approach a feasible solution? [i.e., justify the application of your choice of a particular theory and explain why alternative constructs were rejected. I could choose instead to test Instrumentalist or Circumstantialists models developed among ethnic conflict theorists that rely upon socio-economic-political factors to explain individual-state relations and to apply this theoretical model to periods of war between nations].

The answers to these questions come from a thorough review of the literature and your course readings [summarized and analyzed in the next section of your paper] and the gaps in the research that emerge from the review process. With this in mind, a complete theoretical framework will likely not emerge until after you have completed a thorough review of the literature .

Just as a research problem in your paper requires contextualization and background information, a theory requires a framework for understanding its application to the topic being investigated. When writing and revising this part of your research paper, keep in mind the following:

- Clearly describe the framework, concepts, models, or specific theories that underpin your study . This includes noting who the key theorists are in the field who have conducted research on the problem you are investigating and, when necessary, the historical context that supports the formulation of that theory. This latter element is particularly important if the theory is relatively unknown or it is borrowed from another discipline.

- Position your theoretical framework within a broader context of related frameworks, concepts, models, or theories . As noted in the example above, there will likely be several concepts, theories, or models that can be used to help develop a framework for understanding the research problem. Therefore, note why the theory you've chosen is the appropriate one.

- The present tense is used when writing about theory. Although the past tense can be used to describe the history of a theory or the role of key theorists, the construction of your theoretical framework is happening now.

- You should make your theoretical assumptions as explicit as possible . Later, your discussion of methodology should be linked back to this theoretical framework.

- Don’t just take what the theory says as a given! Reality is never accurately represented in such a simplistic way; if you imply that it can be, you fundamentally distort a reader's ability to understand the findings that emerge. Given this, always note the limitations of the theoretical framework you've chosen [i.e., what parts of the research problem require further investigation because the theory inadequately explains a certain phenomena].

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Conceptual Framework: What Do You Think is Going On? College of Engineering. University of Michigan; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Lynham, Susan A. “The General Method of Theory-Building Research in Applied Disciplines.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 4 (August 2002): 221-241; Tavallaei, Mehdi and Mansor Abu Talib. "A General Perspective on the Role of Theory in Qualitative Research." Journal of International Social Research 3 (Spring 2010); Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Weick, Karl E. “The Work of Theorizing.” In Theorizing in Social Science: The Context of Discovery . Richard Swedberg, editor. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014), pp. 177-194.

Writing Tip

Borrowing Theoretical Constructs from Other Disciplines

An increasingly important trend in the social and behavioral sciences is to think about and attempt to understand research problems from an interdisciplinary perspective. One way to do this is to not rely exclusively on the theories developed within your particular discipline, but to think about how an issue might be informed by theories developed in other disciplines. For example, if you are a political science student studying the rhetorical strategies used by female incumbents in state legislature campaigns, theories about the use of language could be derived, not only from political science, but linguistics, communication studies, philosophy, psychology, and, in this particular case, feminist studies. Building theoretical frameworks based on the postulates and hypotheses developed in other disciplinary contexts can be both enlightening and an effective way to be more engaged in the research topic.

CohenMiller, A. S. and P. Elizabeth Pate. "A Model for Developing Interdisciplinary Research Theoretical Frameworks." The Qualitative Researcher 24 (2019): 1211-1226; Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Undertheorize!

Do not leave the theory hanging out there in the introduction never to be mentioned again. Undertheorizing weakens your paper. The theoretical framework you describe should guide your study throughout the paper. Be sure to always connect theory to the review of pertinent literature and to explain in the discussion part of your paper how the theoretical framework you chose supports analysis of the research problem or, if appropriate, how the theoretical framework was found to be inadequate in explaining the phenomenon you were investigating. In that case, don't be afraid to propose your own theory based on your findings.

Yet Another Writing Tip

What's a Theory? What's a Hypothesis?

The terms theory and hypothesis are often used interchangeably in newspapers and popular magazines and in non-academic settings. However, the difference between theory and hypothesis in scholarly research is important, particularly when using an experimental design. A theory is a well-established principle that has been developed to explain some aspect of the natural world. Theories arise from repeated observation and testing and incorporates facts, laws, predictions, and tested assumptions that are widely accepted [e.g., rational choice theory; grounded theory; critical race theory].

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in your study. For example, an experiment designed to look at the relationship between study habits and test anxiety might have a hypothesis that states, "We predict that students with better study habits will suffer less test anxiety." Unless your study is exploratory in nature, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen during the course of your research.

The key distinctions are:

- A theory predicts events in a broad, general context; a hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a specified set of circumstances.

- A theory has been extensively tested and is generally accepted among a set of scholars; a hypothesis is a speculative guess that has yet to be tested.

Cherry, Kendra. Introduction to Research Methods: Theory and Hypothesis. About.com Psychology; Gezae, Michael et al. Welcome Presentation on Hypothesis. Slideshare presentation.

Still Yet Another Writing Tip

Be Prepared to Challenge the Validity of an Existing Theory

Theories are meant to be tested and their underlying assumptions challenged; they are not rigid or intransigent, but are meant to set forth general principles for explaining phenomena or predicting outcomes. Given this, testing theoretical assumptions is an important way that knowledge in any discipline develops and grows. If you're asked to apply an existing theory to a research problem, the analysis will likely include the expectation by your professor that you should offer modifications to the theory based on your research findings.

Indications that theoretical assumptions may need to be modified can include the following:

- Your findings suggest that the theory does not explain or account for current conditions or circumstances or the passage of time,

- The study reveals a finding that is incompatible with what the theory attempts to explain or predict, or

- Your analysis reveals that the theory overly generalizes behaviors or actions without taking into consideration specific factors revealed from your analysis [e.g., factors related to culture, nationality, history, gender, ethnicity, age, geographic location, legal norms or customs , religion, social class, socioeconomic status, etc.].

Philipsen, Kristian. "Theory Building: Using Abductive Search Strategies." In Collaborative Research Design: Working with Business for Meaningful Findings . Per Vagn Freytag and Louise Young, editors. (Singapore: Springer Nature, 2018), pp. 45-71; Shepherd, Dean A. and Roy Suddaby. "Theory Building: A Review and Integration." Journal of Management 43 (2017): 59-86.

- << Previous: The Research Problem/Question

- Next: 5. The Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 10:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis

Published on 8 July 2022 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Your theoretical framework defines the key concepts in your research, suggests relationships between them, and discusses relevant theories based on your literature review .

A strong theoretical framework gives your research direction, allowing you to convincingly interpret, explain, and generalise from your findings.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Sample problem statement and research questions, sample theoretical framework, your theoretical framework, frequently asked questions about sample theoretical frameworks.

Your theoretical framework is based on:

- Your problem statement

- Your research questions

- Your literature review

To investigate this problem, you have zeroed in on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

- Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

- Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

- Research question : How can the satisfaction of the boutique’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

The concepts of ‘customer loyalty’ and ‘customer satisfaction’ are clearly central to this study, along with their relationship to the likelihood that a customer will return. Your theoretical framework should define these concepts and discuss theories about the relationship between these variables.

Some sub-questions could include:

- What is the relationship between customer loyalty and customer satisfaction?

- How satisfied and loyal are the boutique’s online customers currently?

- What factors affect the satisfaction and loyalty of the boutique’s online customers?

As the concepts of ‘loyalty’ and ‘customer satisfaction’ play a major role in the investigation and will later be measured, they are essential concepts to define within your theoretical framework .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Below is a simplified example showing how you can describe and compare theories. In this example, we focus on the concept of customer satisfaction introduced above.

Customer satisfaction

Thomassen (2003, p. 69) defines customer satisfaction as ‘the perception of the customer as a result of consciously or unconsciously comparing their experiences with their expectations’. Kotler and Keller (2008, p. 80) build on this definition, stating that customer satisfaction is determined by ‘the degree to which someone is happy or disappointed with the observed performance of a product in relation to his or her expectations’.

Performance that is below expectations leads to a dissatisfied customer, while performance that satisfies expectations produces satisfied customers (Kotler & Keller, 2003, p. 80).

The definition of Zeithaml and Bitner (2003, p. 86) is slightly different from that of Thomassen. They posit that ‘satisfaction is the consumer fulfillment response. It is a judgement that a product or service feature, or the product of service itself, provides a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment.’ Zeithaml and Bitner’s emphasis is thus on obtaining a certain satisfaction in relation to purchasing.

Thomassen’s definition is the most relevant to the aims of this study, given the emphasis it places on unconscious perception. Although Zeithaml and Bitner, like Thomassen, say that customer satisfaction is a reaction to the experience gained, there is no distinction between conscious and unconscious comparisons in their definition.

The boutique claims in its mission statement that it wants to sell not only a product, but also a feeling. As a result, unconscious comparison will play an important role in the satisfaction of its customers. Thomassen’s definition is therefore more relevant.

Thomassen’s Customer Satisfaction Model

According to Thomassen, both the so-called ‘value proposition’ and other influences have an impact on final customer satisfaction. In his satisfaction model (Fig. 1), Thomassen shows that word-of-mouth, personal needs, past experiences, and marketing and public relations determine customers’ needs and expectations.

These factors are compared to their experiences, with the interplay between expectations and experiences determining a customer’s satisfaction level. Thomassen’s model is important for this study as it allows us to determine both the extent to which the boutique’s customers are satisfied, as well as where improvements can be made.

Figure 1 Customer satisfaction creation

Of course, you could analyse the concepts more thoroughly and compare additional definitions to each other. You could also discuss the theories and ideas of key authors in greater detail and provide several models to illustrate different concepts.

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Vinz, S. (2022, October 10). Example Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation or Thesis. Scribbr. Retrieved 25 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/example-theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, dissertation & thesis outline | example & free templates, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Understanding and solving intractable resource governance problems.

- In the Press

- Conferences and Talks

- Exploring models of electronic wastes governance in the United States and Mexico: Recycling, risk and environmental justice

- The Collaborative Resource Governance Lab (CoReGovLab)

- Water Conflicts in Mexico: A Multi-Method Approach

- Past projects

- Publications and scholarly output

- Research Interests

- Higher education and academia

- Public administration, public policy and public management research

- Research-oriented blog posts

- Stuff about research methods

- Research trajectory

- Publications

- Developing a Writing Practice

- Outlining Papers

- Publishing strategies

- Writing a book manuscript

- Writing a research paper, book chapter or dissertation/thesis chapter

- Everything Notebook

- Literature Reviews

- Note-Taking Techniques

- Organization and Time Management

- Planning Methods and Approaches

- Qualitative Methods, Qualitative Research, Qualitative Analysis

- Reading Notes of Books

- Reading Strategies

- Teaching Public Policy, Public Administration and Public Management

- My Reading Notes of Books on How to Write a Doctoral Dissertation/How to Conduct PhD Research

- Writing a Thesis (Undergraduate or Masters) or a Dissertation (PhD)

- Reading strategies for undergraduates

- Social Media in Academia

- Resources for Job Seekers in the Academic Market

- Writing Groups and Retreats

- Regional Development (Fall 2015)

- State and Local Government (Fall 2015)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2016)

- Regional Development (Fall 2016)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2018)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2019)

- Public Policy Analysis (Spring 2016)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Summer Session 2011)

- POLI 352 Comparative Politics of Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 2)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Term 1)

- POLI 332 Latin American Environmental Politics (Term 2, Spring 2012)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

Writing theoretical frameworks, analytical frameworks and conceptual frameworks

Three of the most challenging concepts for me to explain are the interrelated ideas of a theoretical framework, a conceptual framework, and an analytical framework. All three of these tend to be used interchangeably. While I find these concepts somewhat fuzzy and I struggle sometimes to explain the differences between them and clarify their usage for my students (and clearly I am not alone in this challenge), this blog post is an attempt to help discern these analytical categories more clearly.

A lot of people (my own students included) have asked me if the theoretical framework is their literature review. That’s actually not the case. A theoretical framework , the way I define it, is comprised of the different theories and theoretical constructs that help explain a phenomenon. A theoretical framework sets out the various expectations that a theory posits and how they would apply to a specific case under analysis, and how one would use theory to explain a particular phenomenon. I like how theoretical frameworks are defined in this blog post . Dr. Cyrus Samii offers an explanation of what a good theoretical framework does for students .

For example, you can use framing theory to help you explain how different actors perceive the world. Your theoretical framework may be based on theories of framing, but it can also include others. For example, in this paper, Zeitoun and Allan explain their theoretical framework, aptly named hydro-hegemony . In doing so, Zeitoun and Allan explain the role of each theoretical construct (Power, Hydro-Hegemony, Political Economy) and how they apply to transboundary water conflict. Another good example of a theoretical framework is that posited by Dr. Michael J. Bloomfield in his book Dirty Gold, as I mention in this tweet:

In Chapter 2, @mj_bloomfield nicely sets his theoretical framework borrowing from sociology, IR, and business-strategy scholarship pic.twitter.com/jTGF4PPymn — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) December 24, 2017

An analytical framework is, the way I see it, a model that helps explain how a certain type of analysis will be conducted. For example, in this paper, Franks and Cleaver develop an analytical framework that includes scholarship on poverty measurement to help us understand how water governance and poverty are interrelated . Other authors describe an analytical framework as a “conceptual framework that helps analyse particular phenomena”, as posited here , ungated version can be read here .

I think it’s easy to conflate analytical frameworks with theoretical and conceptual ones because of the way in which concepts, theories and ideas are harnessed to explain a phenomenon. But I believe the most important element of an analytical framework is instrumental : their purpose is to help undertake analyses. You use elements of an analytical framework to deconstruct a specific concept/set of concepts/phenomenon. For example, in this paper , Bodde et al develop an analytical framework to characterise sources of uncertainties in strategic environmental assessments.

A robust conceptual framework describes the different concepts one would need to know to understand a particular phenomenon, without pretending to create causal links across variables and outcomes. In my view, theoretical frameworks set expectations, because theories are constructs that help explain relationships between variables and specific outcomes and responses. Conceptual frameworks, the way I see them, are like lenses through which you can see a particular phenomenon.

A conceptual framework should serve to help illuminate and clarify fuzzy ideas, and fill lacunae. Viewed this way, a conceptual framework offers insight that would not be otherwise be gained without a more profound understanding of the concepts explained in the framework. For example, in this article, Beck offers social movement theory as a conceptual framework that can help understand terrorism . As I explained in my metaphor above, social movement theory is the lens through which you see terrorism, and you get a clearer understanding of how it operates precisely because you used this particular theory.

Dan Kaminsky offered a really interesting explanation connecting these topics to time, read his tweet below.

I think this maps to time. Theoretical frameworks talk about how we got here. Conceptual frameworks discuss what we have. Analytical frameworks discuss where we can go with this. See also legislative/executive/judicial. — Dan Kaminsky (@dakami) September 28, 2018

One of my CIDE students, Andres Ruiz, reminded me of this article on conceptual frameworks in the International Journal of Qualitative Methods. I’ll also be adding resources as I get them via Twitter or email. Hopefully this blog post will help clarify this idea!

You can share this blog post on the following social networks by clicking on their icon.

Posted in academia .

Tagged with analytical framework , conceptual framework , theoretical framework .

By Raul Pacheco-Vega – September 28, 2018

7 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post .

Thanks, this had some useful clarifications for me!

I GOT CONFUSED AGAIN!

No need to be confused!

Thanks for the Clarification, Dr Raul. My cluttered mind is largely cleared, now.

Thanks,very helpful

I too was/am confused but this helps 🙂

Thank you very much, Dr.

Leave a Reply Cancel Some HTML is OK

Name (required)

Email (required, but never shared)

or, reply to this post via trackback .

About Raul Pacheco-Vega, PhD

Find me online.

My Research Output

- Google Scholar Profile

- Academia.Edu

- ResearchGate

My Social Networks

- Polycentricity Network

Recent Posts

- “State-Sponsored Activism: Bureaucrats and Social Movements in Brazil” – Jessica Rich – my reading notes

- Reading Like a Writer – Francine Prose – my reading notes

- Using the Pacheco-Vega workflows and frameworks to write and/or revise a scholarly book

- On framing, the value of narrative and storytelling in scholarly research, and the importance of asking the “what is this a story of” question

- The Abstract Decomposition Matrix Technique to find a gap in the literature

Follow me on Twitter:

Proudly powered by WordPress and Carrington .

Carrington Theme by Crowd Favorite

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Qualitative data analysis and the use of theory.

- Carol Grbich Carol Grbich Flinders University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.554

- Published online: 23 May 2019

The role of theory in qualitative data analysis is continually shifting and offers researchers many choices. The dynamic and inclusive nature of qualitative research has encouraged the entry of a number of interested disciplines into the field. These discipline groups have introduced new theoretical practices that have influenced and diversified methodological approaches. To add to these, broader shifts in chronological theoretical orientations in qualitative research can be seen in the four waves of paradigmatic change; the first wave showed a developing concern with the limitations of researcher objectivity, and empirical observation of evidence based data, leading to the second wave with its focus on realities - mutually constructed by researcher and researched, participant subjectivity, and the remedying of societal inequalities and mal-distributed power. The third wave was prompted by the advent of Postmodernism and Post- structuralism with their emphasis on chaos, complexity, intertextuality and multiple realities; and most recently the fourth wave brought a focus on visual images, performance, both an active researcher and an interactive audience, and the crossing of the theoretical divide between social science and classical physics. The methods and methodological changes, which have evolved from these paradigm shifts, can be seen to have followed a similar pattern of change. The researcher now has multiple paradigms, co-methodologies, diverse methods and a variety of theoretical choices, to consider. This continuum of change has shifted the field of qualitative research dramatically from limited choices to multiple options, requiring clarification of researcher decisions and transparency of process. However, there still remains the difficult question of the role that theory will now play in such a high level of complex design and critical researcher reflexivity.

- qualitative research

- data analysis

- methodologies

Theory and Qualitative Data Analysis

Researchers new to qualitative research, and particularly those coming from the quantitative tradition, have often expressed frustration at the need for what appears to be an additional and perhaps unnecessary process—that of the theoretical interpretation of their carefully designed, collected, and analyzed data. The justifications for this process have tended to fall into one of two areas: the need to lift data to a broader interpretation beyond the Monty Pythonesque “this is my theory and it’s my very own,” to illumination of findings from another perspective—by placing the data in its relevant discipline field for comparison with previous theoretical data interpretations, while possibly adding something original to the field.

“Theory” is broadly seen as a set of assumptions or propositions, developed from observation or investigation of perceived realties, that attempt to provide an explanation of relationships or phenomena. The framing of data via theoretical imposition can occur at different levels. At the lowest level, various concepts such as “role,” “power,” “socialization,” “evaluation,” or “learning styles” refer to limited aspects of social organization and are usually applied to a specific group of people.

At a more complex level, theories of the Middle Range, identified by Robert Merton to link theory and practice, are used to build theory from empirical data. These tend to be discipline specific and incorporate concepts plus variables such as “gender,” “race,” or “class.” Concepts and variables are then combined into meaningful statements, which can be applied to more diverse social groups. For example, in education an investigation of student performance could emphasize such concepts as “safety,” “zero bullying,” “communication,” and “tolerance,” with variables such as “race” and “gender” to lead to a statement that good microsystems and a focus on individual needs are necessary for optimal student performance.

The third and most complex level uses the established or grand theories such as those of Sigmund Freud’s stages of children’s development, Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, or Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems, which have been widely accepted as meaningful across a number of disciplines and provide abstract explanations of the uniformity of aspects of social organization, social behavior, and social change.

The trend in qualitative research regarding the application of chosen levels of theory has been generally either toward theory direction/verification or theory generation, although the two are often intertwined. In the first, a relevant existing theory is chosen early and acts as a point of critical comparison for the data to be collected. This approach requires the researcher to think theoretically as s/he designs the study, collects data, and collates it into analytical groupings. The danger of theory direction is that an over focus on a chosen theoretical orientation may limit what the researcher can access or “see” in the data, but on the upside, this approach can also enable the generation of new theoretical aspects, as it is rare that findings will fall precisely within the implications of existing statements. Theory generation is a much looser approach and involves either one or a range of relevant levels of theory being identified at any point in the research process, and from which, in conjunction with data findings, some new combination or distillation can enhance interpretation.

The question of whether a well-designed study should negate the need for theoretical interpretation has been minimally debated. Mehdi and Mansor ( 2010 ) identified three trends in the literature on this topic: that theory in qualitative research relates to integrated methodology and epistemology; that theory is a separate and additional element to any methodological underpinnings; and that theory has no solid relationship with qualitative research. No clear agreement on any of these is evident. Overall, there appears to be general acceptance that the process of using theory, albeit etically (imposed) or emically (integrated), enhances outcomes, and moves research away from being a-theoretical or unilluminated by other ideas. However, regarding praxis, a closer look at the issue of the use of theory and data may be in order. Theoretical interpretation, as currently practiced, has limits. To begin with, the playing field is not level. In the grounded theory tradition, Glaser and Strauss ( 1967 ) were initially clear that in order to prevent undue influence on design and interpretation, the researcher should avoid reviewing the literature on a topic until after some data collection and analysis had been undertaken. The presumption that most researchers would already be well versed in theory/ies and would have a broad spectrum to draw on in order to facilitate the constant comparative process from which data-based concepts could be generated was found to be incorrect. Glaser ( 1978 ) suggested this lack could be improved at the conceptual level via personal and professional reflexivity.

This issue became even more of a problem with the advent of practice-led disciplines such as education and health into the field of qualitative research. These groups had not been widely exposed to the theories of the traditional social sciences such as sociology, psychology, and philosophy, although in education they would have been familiar with John Dewey’s concept of “pragmatism” linking learning with hands-on activity, and were more used to developing and using models of practice for comparison with current realities. By the mid- 20th century , Education was more established in research and had moved toward the use of middle range theories and the late 20th-century grand theorists: Michel Foucault, with his emphasis on power and knowledge control, and Jurgen Habermas, with his focus on pragmatism, communication, and knowledge management.

In addition to addictive identification with particular levels of theory and discipline-preferred theories and methods, activity across qualitative research seems to fall between two extremes. At one end it involves separate processes of data collection and analysis before searching for a theoretical framework within which to discuss the findings—often choosing a framework that has gained traction in a specific discipline. This “best/most acceptable fit” approach often adds little to the relevant field beyond repetition and appears somewhat forced. At the other extreme there are those who weave methods, methodologies, data, and theory throughout the whole research process, actively critiquing and modifying it as they go, usually with the outcome of creating some new direction for both theory and practice. The majority of qualitative research practice, however, tends to fall somewhere between these two.

The final aspect of framing data lies in the impact of researchers themselves, and the early- 21st-century emphasis is on exposing relevant personal frames, particularly those of culture, gender, socioeconomic class, life experiences such as education, work, and socialization, and the researcher’s own values and beliefs. The twin purposes of this exposure are to create researcher awareness and encourage accountability for their impact on the data, as well as allowing the reader to assess the value of research outcomes in terms of potential researcher bias or prejudice. This critical reflexivity is supposed to be undertaken at all stages of the research but it is not always clear that it has occurred.

Paradigms: From Interactionism to Performativity

It appears that there are potentially five sources of theory: that which is generally available and can be sourced from different disciplines; that which is imbedded in the chosen paradigm/s; that which underpins particular methodologies; that which the researcher brings, and that which the researched incorporate within their stories. Of these, the paradigm/s chosen are probably the most influential in terms of researcher position and design. The variety of the sets of assumptions, beliefs, and researcher practices that comprise the theoretical paradigms, perspectives, or broad world views available to researchers, and within which they are expected to locate their individual position and their research approach, has shifted dramatically since the 1930s. The changes have been distinct and identifiable, with their roots located in the societal shifts prompted by political, social, and economic change.

The First Wave

The Positivist paradigm dominated research, largely unquestioned, prior to the early 20th century . It emphasized the distancing of the researcher from his/her subjects; researcher objectivity; a focus on objective, cause–effect, evidence-based data derived from empirical observation of external realities; experimental quantitative methods involving testing hypotheses; and the provision of finite answers and unassailable future predictions. From the 1930s, concerns about the limitations of findings and the veracity of research outcomes, together with improved communication and exposure to the worldviews of other cultures, led to the advent of the realist/post-positivist paradigm. Post-positivism, or critical realism, recognized that certainty in proving the truth of a hypothesis was unachievable and that outcomes were probably limited to falsification (Popper, 1963 ), that true objectivity was unattainable and that the researcher was most likely to impact on or to contaminate data, that both qualitative and quantitative approaches were valuable, and that methodological pluralism was desirable.

The Second Wave