Russia Travel Blog | All about Russia in English

- About our blog

- RussiaTrek.org

Sidebar →

- Architecture

- Entertainment

- RussiaTrek.org News

- Send us a tip with a message

- Support RussiaTrek.org

- Travel Guide to Ukraine

- Comments RSS

← Sidebar

The USA vs. Russia Education Compared

No comments · Posted by Alex Smirnov in Education

The US and Russia have fairly old systems of education. They have several similarities and also main differences. In both nations, the governments are committed to a learned population that can continually thrust the nations forward economically, socially, and politically.

Formal education, especially higher education, contributes significantly to the high level of technological advancements observed in the two largest nations in terms of landmass. The similarities and differences in their education systems can be summarized as follows.

Education system controlled by the government

Both nations have government and private schools but they all follow an education system set by the government. The department of education sets the curriculum and controls what schools should teach, starting from the lowest grades to the highest.

This kind of system ensures a unified form of information for all students who go through the education system. To the governments, it is the best way to bring their citizens to a point where they will understand the nation’s dream and play their role towards its fulfillment.

Critical thinking versus memorization

In terms of teaching, American education differs from Russian. The American teacher creates an environment where the learner can actively use his or her mind to create a solution. The teacher will guide the learner on how to create the solution, but at the same time gives them space for independent thinking.

For example, if the students are learning a scientific principle, the teacher allows their students to think about how it works practically. They will do so through experiments, games, writing, and so on.

The system is different in Russia. The Russian teacher is interested more in answers than the process. The student who provides instant answers to a question is more favored than the slow student.

This disparity has turned the students into a community of crammers where students memorize answers instead of stating the facts. As a result, they get challenged when facing real-life after they complete schooling.

Essay writing assistance

Essay writing continues to be a major method for testing student knowledge while in college. It is also the form of testing that most students would wish was not part of college education study. The main reason is due to the hardships many students face when writing essays.

The solution is for the students to seek essay writing help from professional writers. Edubirdie is an established professional academic writing service provider for all college assignments. It includes essays, thesis, dissertations, term papers and much more.

Schooling in a geographical location

Preschool classes in the American system are the responsibility of parents/guardians. They teach their children the basics of education before taking them to grade one. In Russia, there are official early childhood schools and no child can join primary school without having gone through a pre-school. As a result, parents are less concerned with teaching their children at home.

In America, schools are classified into districts. A child can only attend a school within his or her district. If a parent wishes to transfer their child to a school in another district, the only option is to move and live in that district.

In Russia, however, every parent is free to take their child to any school they desire as long as they are willing to study in that school. During admission, the priority is given to children from the district before admitting those from other districts.

College education

Russia does not have too many requirements to join college. All that is needed is for the student to pass the national exam and attain the relevant college entry points. Every academic year has two semesters and each semester ends with an exam. In some instances, students can access higher education for free.

In the US, entry into college has several requirements . Apart from the exams, a student must be recommended by a teacher, be good in extra curriculum activities, write an essay, and be interviewed. During their study, regular knowledge and special talents are taken into account. Higher education in the US is paid for by all students. Special cases need to apply for scholarships or grants.

The level of literacy in any nation is first judged by the number of citizens that have gone through formal education. Every government should create a conducive environment for its citizens to pursue education to the highest level. The governments of Russia and America have played a significant role in ensuring their masses are educated. There are many more chances to improve the current system of education to a better one that produces critical thinkers who can become change agents in technology and the economy.

Author’s Bio:

Julius Sim is the Head of Support Team at EduBirdie and has been a major force behind the academic writing service’s massive success. He has been instrumental in reducing delivery errors to almost zero and ensuring fast resolution to student queries and issues. In his free time, he enjoys walking his pet and watching movies and following business news.

Tags: No tags

You might also like:

The ancient citadel of Naryn-Kala in Derbent

4 Things To Know Before Visiting Russia >>

No comments yet.

Leave a reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

Russian education system: trends, dimensions, quality assurance

Key transformations: historical overview

As is well-known, the United Nations Organization declared 2005-2014 the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development.

The global goal of this initiative is to attain such a level of education that could meet the crucial challenges of the current century.

Therefore, new content, new quality, and a new level of cooperation are attributes of education in the XXI century.

The governments of many countries initiated reformation of their national educational systems. Russia is no exception. Substantial transformations are going on in this country as well. The following is a retrospective list of some significant events which have become core landmarks for renovations of the Russian educational system.

2003—the Russian Federation officially joined the Bologna process. The objective was Russia’s integration and participation in the processes of establishing and harmonization of the common European Education Area. As a result:

- Russia’s higher education adopted a multi-level education system: bachelor’s and master’s programs (getting education in some disciplines, for example, in Engineering and Medicine, takes up five years and corresponds to a separate level—a specialist’s program);

- the European Credits Transfer System (ECTS) was implemented;

- a Diploma Supplement compatible with a common-European Official Transcript is granted upon successful graduation;

- the system of foreign academic certificates recognition in the RF and Russian academic certificates recognition in foreign countries, members of the Bologna Declaration, was established;

- comparable methodologies and assessment criteria were developed and are in effect now, which makes it possible to perform public professional assessment of Russian study programs on the international level;

- by 2020 nearly 100% of higher education institutions will meet the core requirements of the Bologna process. This final indicator of the Bologna process implementation in Russia was defined in the Federal Targeted Program for 2016-2020.

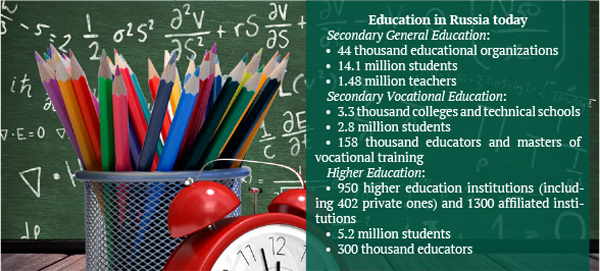

FACT The Russian Federation today:

- occupies the ninth position among 223 countries of the total population (146 million people);

- belongs to the countries with a high level of the Human Development Index (the fiftieth position among 188 countries);

- belongs to the countries with the maximum values of the Gross Enrollment Ratio in the age of 5-18 (98.7% in 2012, the expected level in 2020 is 99.4%);

- occupies the 43rd position in the Global Innovation Index ranking among 128 countries. In comparison with 2012, the country has moved eight positions up in this ranking;

- according to experts' assessment, Russia's upward trend in the Global Innovation Index ranking was substantially impacted by its traditionally high ranking positions in a number of indicators (sub-indexes) reflecting the quality of human capital assets, predominantly: Education (the 27th position among 128 countries), Higher Education (the 23rd position), Research and Development (the 25th position), Knowledge Creation (the 21st position).

2006—the National Priority Project Education was initiated in Russia. The project aimed at performing complex modernization of all education levels in order to achieve new quality corresponding to the current societal demands. As a result:

- the material and technical resources of educational organizations were renewed;

- the top educational organization development programs competed for governmental support;

- the mechanism of identifying high-ranking higher education institutions (federal universities) as well as their government support was developed and validated;

- the experience gained by high-ranking educational organizations is incorporated into practice of educational activity;

- for two years of the project implementation (2006-2008) the state gained unique managerial experience which shaped the contemporary national policy in education.

- 57 higher educational institutions, 9,000 secondary schools, 340 educational institutions of primary and secondary vocational education got financial support for implementation of their innovative development programs;

- 40 thousand best educators and 21 thousand talented young people received monetary awards;

- over 800 thousand school teachers received an additional monthly payment for classroom management;

- Russiaʼs educational organizations received about 55 thousand units of new equipment and almost 10 thousand school buses.

2008— the beginning of a gradual implementation of a new generation of the Federal State Education Standards (FSES) based on a competency building approach. The objective was to adapt the content of education to the latest personal, economic, societal and state demands. Due to the framework nature of the new generation standards educational organizations gained greater independence in terms of education content. For instance, while developing bachelor’s programs a higher education institution is responsible for determining independently up to 50% of courses (modules), and as for master’s programs—up to 70%. As a result:

- educational organizations obtained a tool for a prompt and flexible response to dynamic demands of the contemporary economy and society;

- employers gained an opportunity to immediately participate in designing curricula and programs. Today the academic community and employers’ associations are actively involved in the development and alignment of professional and educational standards. This work is coordinated by the Presidential National Council for Professional Qualifications, which was established in 2014. Among other tasks the Council should facilitate the international cooperation in developing national systems of professional qualifications;

- incorporation of the new generation of the Federal State Educational Standards along with other measures assured the achievement of new learning outcomes, continuity of education levels, practical implementation of the Bologna process requirements including the development of the “lifelong learning” model (LLL).

2012—the new Federal Law “On Education in the Russian Federation” was enacted. The objective was to establish a legal environment adequate of the national educational system. As a result:

- the constitutional right of each citizen of the RF for education was confirmed once again;

- the state guaranteed an availability and a free-of-charge basis of general education and secondary vocational education as well as an opportunity to get free higher education on a competition basis;

- citizens’ right for a distance, electronic, network or family learning was legislated for the first time ever;

- the RF indicated its interest in improving international cooperation in education, including the development of academic and student mobility, implementation of joint educational programs, carrying out joint research, etc.;

- the excessive type segmentation of educational organizations was eliminated and a new structure of higher education was formed;

- the RF’s education level system was adapted to the requirements of the Bologna Declaration and the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED).

Education Levels in the Russian Federation:

- pre-school education (ISCED 0);

- primary general education (ISCED 1);

- basic general education (ISCED 2);

- secondary general education (ISCED 3);

- secondary vocational education: craftsman and skilled worker training (ISCED 4) / mid-ranking specialist training (ISCED 5);

- higher education: Bachelor (ISCED 6);

- higher education: Master (or a five-year Higher Education Specialist) (ISCED 7);

- higher education: academic and teaching staff training, clinical residency, assistantship-internship (ISCED 8).

Changes in the course: some examples

One of the key objectives of the initiated reforms is improving the quality of the Russian educational system. Is it a tangible objective? Definitely, yes. Here are some examples of a positive development of school and vocational pre-tertiary education.

Thus, according to PISA 2015 results (the Program for International Student Assessment) in By 2020 Russia intends to become one of the 15 top performers of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) as well as to achieve the five top countries in Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS).

One of the main factors of school education quality improvement is creation of innovative learning environment in 100% of Russian general education organizations by 2020.

In 2015 the WSI General Assembly made a decision to hold the WorldSkills Competition-2019 in Kazan, Russia. The results of this WSI Competition will be organized in its Heritage, comprising cases of the best global and Russian skills practices and skilled worker training. WorldSkills Academia Russia will translate the cases into the vocational education system ( here ).

70 countries, Russia has seen slight improvements in all focus areas.

Particularly, in Science the country moved 5 places up from 37th in 2012 to 32nd in 2015.

In Reading Russia was ranked 26th in 2015, that was 16 places up in comparison with its previous performance in 2012.

In the field of Mathematics Russian students also achieved a significant progress: in 2015 Russia occupied the 23rd position in Maths, it was an 11-line better performance than in 2012.

The following example can illustrate the development and achievements of the vocational education system of the Russian Federation. Therefore, at the end of 2012 Russia joined the international non-commercial movement WorldSkills International (WSI) which today unites 75 countries of the world. In 2014 the Russian national team participated in Euroskills, the largest European skills competition for the title Best of Europe, for the first time and was ranked 11th. However, two years later in 2016 the Russian team became the leader of EuroSkills-2016 competitions and won the first place in the team classification among 28 European countries. The similar improvement was demonstrated by the WorldSkills Russia team in the WorldSkills Competitions.

By 2020 it is planned to develop a new model of a highly competitive national system of vocational education meeting the needs of modern economy. As a result, advanced hi-tech industries will employ annually up to 50 thousand graduates from secondary vocational education organizations that train skilled workers according to the WS standards.

The success like this is predictible. The fact is that Russia began an active upgrading of vocational skills training to comply with the international standards of WorldSkills (WS). This objective is declared to be one of essential national strategies in the area of secondary vocational education. Particularly, within this strategy:

- by now the TOP-50 list of the most in-demand and prospective jobs and fastest growing occupations is compiled on the federal level. In order to fit in students will undergo training complying with the best world standards and advanced technologies (the list includes, for example, such skills as air drone operators, mechatronics, mobile robotics;

- from 2017 the State Final Certification in vocational education organizations will include a demo exam according to the WorldSkills standards in 41 competencies. All the students who have passed the demo exam along with the Diploma of Secondary Vocational Education will be awarded a qualification recognized by enterprises working according to the WS standards;

- from 2018 specialized Centers of Excellence accredited according to the WS standards will be functioning in the regions of Russia. By 2020 it is expected that 175 such centers will be established in the country;

- from 2020 at least 40% of graduates in the TOP- 50 skills should have qualification certificates or medals of excellence according to the WS standards.

Higher education: new architecture

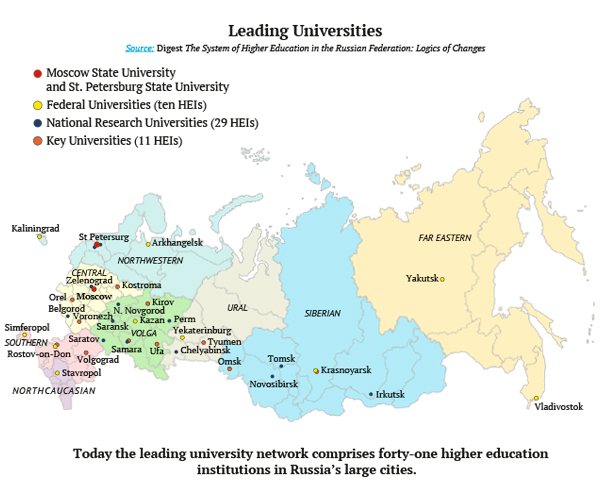

The strategic goal of a new quality level of Russia’s education which would meet challenges and demands of the XXI century is applied to Russian higher education to its full extent. For the past decade, since 2006, the government introduced a number of large-scale changes in the structure of higher education. The core of these changes is the establishment of a modern effective network of Russian leading HEIs which should become the driving force necessary to attain the strategic goal.

Nowadays such a network is well-established. Originally it included 41 higher education institutions: ten federal universities, 29 national research universities, and two oldest universities of the country—Lomonosov Moscow State University and Saint Petersburg State University. The latter two got a special status of unique academic organizations of national significance. In 2010 all the above mentioned educational institutions formed the Association of Leading Universities (for more details refer to here ). In 2016 another eleven universities joined this leading HEIs network as they got the status of a key university due to participation in the contest of the Ministry of Education and Science of the RF. The second stage of the Key University contest takes place in 2017. According to the Ministry, another 19 educational institutions will become key universities.

It should be noted, that most of the leading universities are located in the largest cities of Russia such as Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Kazan, Samara, Yekaterinburg, Novosibirsk, Tomsk, and others.

The brief description of the mentioned HEI categories is as follows.

Federal university. The name federal in this case relates to the mission and the location of such universities. The territory of Russia is divided into macro-regions which are called federal districts. Therefore, the strategic mission of a federal university is creation and development of competitive human resources in the district as well as ensuring its social, economic and technological progress through advanced intellectual, research and educational opportunities, solutions, and cases. Such solutions and practices should be shaped on the ground of close integration of education, science and employers representing the main industries of a federal district. Becoming such an innovative institutional integrator is the key strategic task of a federal university.

Ten federal universities were established in Russia in the period from 2006 to 2016.

The activity of each federal university is conditioned by an individual long-term development program which contains target indicators in HEI’s priorities—educational, scientific, or international (integration of Russian education into the international academic area and export of educational services). It is essential that these indicators are mutually related with strategic indicators set in the programs of socioeconomic development of the macroregions—the federal districts. In addition, the development program of each federal university complies with the priority growth areas in science, technology and engineering in the Russian Federation and with the key technology list.

The priority and key technology list (approved by the President Decree in 2011 and amended in 2015) defines the main trends in the scientific, technological, economic development of the country. It frames the long-term benchmarks for Russian higher education in general and for the leading Russian universities in particular—what human resources will be necessary for the science and research sector and for the national economy within the coming ten to twenty years.

FACT Over a quarter of the total number of international educators working in Russiaʼs higher education institutions are employed by twenty-nine national research universities.

National research university. The project focusing on the establishment of a national research university pool started in 2008. The higher education institution nominated for this category (as well as related budget funding), similar to a federal university, should generate a strategic program of its development for the period of ten years and defend it in the open contest organized by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation. National research universities are selected based on the outcomes of a thorough analysis and the previous development dynamics of the applicant university. The analysis comprises such categories as human resources, an educational and research infrastructure, efficiency of academic and research activities, certificates of international and national recognition as well as the quality, feasibility and expected outcomes of the development program submitted to the contest. Despite the tough selection requirements almost every third state university in Russia applied for participation in the contest procedure. After the two-stage contest held during two years, by May 2010 the Russian network of national research universities had been finally established.

Nowadays the mentioned network includes 29 educational institutions. The mission of a national research university is to a large extend similar to the strategic goals and objectives of a federal university. The difference is in the emphasis put by a federal university on academic and human resource aspects of the innovative development of Russia’s macroregions, while a national research university plays a specific role in the development of world class high technology, in knowledge creation and in training a new generation of Russian researchers, scientists, and academic staff for higher education. According to this mission every national research university assumes the program obligations to improve the priority growth areas corresponding to its profile. The comprehensive list of priority growth areas (totally 106 fields) is compiled with the view of the main objectives of the innovative and technological development of the Russian Federation; the priority growth areas are distributed among 29 national research universities.

Key university. Another essential element of the new up-to-date architecture of Russian higher education is a HEI category which is called key universities (for more details refer to official web-site).

- Russia is one of the global leaders in the development of the worldwide industries of a knowledge-driven economy;

- Russia is in the top 10 exporters of intellectual property;

- Russia is in the top 10 of the Global Innovation Index;

- Russia has a positive balance of the talents engaged in the field of science, technology and innovations;

- the average increment rate of the new NTI-economy is 9% per year;

- Russian companies created ten global technology brands.

The universities are selected to this category on a competitive basis, too. The winners of the contest are defined based on their five-year development program. In addition to this program, the applicant university should meet another eligibility requirement: it has to undergo a reorganization procedure and deliberately merge with some other state educational institutions in the same municipality. According to the program initiators, such a transformation will require integration of all resources of the universities which will lead to the improved efficiency and, consequently, in the advanced quality of education in a newly organized university. At least, such expectations are clearly expressed in the government’s requirements to this new category of universities. So, after the implemetation of a five-year development program a key university should feature seven headline parameters which comprise the following: at least ten thousand full-time students; at least two billion rubles as a university’s annual revenue; at least twenty majors or profiles in which the university delivers main study programs; the postgraduate and master student ratio in relation to the total number of students—at least 20%; income from research—at least 150,000 rubles per academic researcher; a number of publications indexed in the international Web of Science and Scopus systems—at least ten and twelve, respectively, per hundred of academic researchers annually.

The first stage of this contest was accomplished in 2016. As a result, eleven educational institutions were granted the status of a key university.

In 2017 the initiator of the contest, the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation will hold the second stage—another 19 key universities will be determined. The third stage is planned for 2018.

- scope of research and development per academic researcher—twice as high as the average in the higher education system;

- publication activities—3.5 times as high as the average in the higher education system.

Universities as development centers

According to the Global Innovation Index mentioned above, Russia is ranked 43rd among 128 countries. The crucial trend found out by this annual survey is the positive dynamics of the country’s innovative development: in comparison with 2012 the Russian Federation went eight positions up. The experts of the Global Innovation Index state that this improvement was attained due to conventionally high rankings of Russia’s education—particularly those of higher education and a research sector.

Indeed, one of the major strategic concerns of Russia is the establishment of the up-to-date National Innovation System (NIS). Creation of such a system could ensure the country a rightful place in the globalized, complicated and fast-developing world of the XXI century. In Russia this understanding manifests itself in long-term strategic initiatives and programs developed and being implemented on the national level with a focus on consistent structuring of the domestic NIS. Undoubtedly, the ultimate fulfillment of the nation’s intellectual and creative potential has a great significance for attaining this goal. Higher education as one of the main social institutions engaged in generating and developing human capital assets plays a crucial role in the implementation of these initiatives and programs. Some of them will be discussed further in this chapter.

National technology initiative (NTI). The idea of the NTI was first articulated by the President of Russia in December 2014 in his Address to the Federal Assembly, “On the basis of long-term forecasting, it is necessary to understand what challenges Russia will face in 10-15 years, which innovative solutions will be required in order to ensure national security, quality of life, development of the sectors of the new technological order.” During the past two years the organizational structure for the NTI implementation was established and the operators and key participants were defined. Namely, the federal Ministry of Education and Science was entrusted with coordinating research, educational, and technological, together with the relevant ministries, activities within the NTI. In the framework of several large-scale foresight sessions the experts— representatives of the academic community, hi-tech and venture businesses, governmental authorities and professional associations—created roadmaps containing schedules of the NTI implementation. The NTI directions include nine industry-specific Nets of the Market group as well as thirteen fields of the Technologies group. These Nets, inherently representing fundamentally new advanced technology markets, focus on developing transnational corporations of the Russian origin.

The leading Russian universities are expected to become a scientific and technological foundation for the NTI implementation. On the one hand, the universities’ mission is to train highly qualified professionals in the fields demanded by companies participating in the NTI; on the other hand, the universities to a great extent are becoming the main generators and stakeholders of technological innovations while the universities spin-offs should be the NTI market leaders and shape new markets (refer to source).

Since 2004 in Russia the number of researchers under 39 has increased by one third. This trend is more characteristic of higher education: nowadays young researchers make over 60% of Russian university employees.

At present the representatives of the leading higher education institutions, the expert community, and the companies operating the NTI are model, which is believed to be similar to the concept of University 3.0, as well as in determining forms of the implementation of the NTI projects and programs within universities (for more information on the National Technology Initiative refer to here ).

Russia’s innovative territorial clusters should become the global leaders in their investment prospects. The clusters play one of the key roles in creation and upgrading of 25 million high-tech work positions in the country by 2025.

For more information on Russia’s innovative territorial clusters and on Russia’s cluster policy refer to here and here .

Innovative territorial clusters (ITC). Nowadays clusters playing the role of a driving force for the innovative economy and generators of a new technological paradigm are developing in many countries. The main mission of a cluster is to create conditions facilitating the fastest and effective transfer of research and development from laboratories to business. The first cluster projects were initiated in Europe in the 1980s. However, the real cluster boost began worldwide in the 2000s. By 2005 about 1.5 thousand clusters operated in the world, while over 60% of them were established within this five-or-six-year period.

Russia generated and accepted the concept of the cluster policy in 2008, and since 2012 after the federal contest 26 pilot innovative territorial clusters have emerged in the country as their development programs have been supported by the state (the total number of clusters in the RF is over 125). The characteristic feature of innovative territorial clusters is their location in the regions traditionally featuring intensive research, engineering, and manufacturing activities.

Many prominent Russian research organizations, universities, and manufacturing companies participate in the ITCs. According to the experts, by the present time each cluster has developed close partnership relations with at least two or three universities. In Russia the interaction between a cluster and a university can be implmented in three ways: 1) delivering study programs in the cluster’s priority fields, aiming at training, retraining and further education of human resources, especially engineers; 2) doing joint applied research with business companies; 3) shared use of the HEIs’ innovative infrastructure. One of the generally determined algorithms for partnerships, that has already proved its efficiency, can be described as follows: the university (as a source of innovations and projects) –> the venture fund (as a source of investments) –> the innovative territorial cluster (as a user of the end intellectual product).

Strategy—2035. In December 2016 the Strategy of Russia’s Research and Technological Development was officially enacted; it is a long-term plan until 2035. The goal of the Strategy is the establishment of an effective system for growing and extensive utilization of the nation’s intellectual potential. This novel document is the first to formulate the so-called “grand challenges” for future Russia. They can be explained as “a combination of problems, threats and opportunities,” which already in the near-term prospect will demand large-scale institutional solutions. Among the most significant “grand challenges” are the following: issues of demography, ecology, energy efficiency, food security and national security, global competitiveness of the Russian Federation. However, the challenge list begins with the crucial for Russia statement—it deals with “depleted possibilities of the economic growth due to extensive use of primary resources.” The only appropriate solution to this and other “grand challenges” is to replace the extensive national development model with the innovative one, thus making Russia’s research and technological complex a top-priority in the national development.

The research and development sector of higher education, that left behind the other Russian research and development segments (i.e. academic and corporate), should play an essential role in the fulfillment of the mentioned task. Thus, for twenty years, from 1995 to 2014, the number of higher education institutions engaged in R&D increased almost twice—from 395 up to 700. At the same time, the number of university R&D employees increased by one third—from 35.5 thousand up to 44.3 thousand people. Moreover, from 2004 to 2014 the Russian universities increased internal expenses on R&D by 28 times—from 2.77 billion rubles up to 77.66 billion rubles. In addition to it, the Russian university R&D sector has another peculiarity—it comprises the majority of young researchers.

The Strategy focuses on the further development of higher education and R&D. Namely, the following directions are outlined: transforming some leading Russian HEIs into entrepreneurial universities; delivering educational programs on technology entrepreneurship; establishing professional management of research and development sectors at universities; delivering special educational programs for university administrators in compliance with international standards; improving the management of university research laboratories through the implementation of advanced and flexible rules (standards, guidelines) regulating their activities; establishing a special register and a special ranking of research universities in the Russian Federation.

Russian universities should become a base for the system of centers of excellence and centers of competence. The objective of centers of excellence is to ensure the universities’ top positions in the international rankings, which are compiled by surveying or engineering organizations, as well as in the bibliometric systems. Centers of competence are supposed to ensure availability of advanced technologies for the Russian manufacturing sector and for other research or educational institutions.

Another idea is to establish in Russia innovative territorial clusters on the base of university campuses and “innovative districts” in metroplexes for concentrating research and innovative activities. Some experience of the implementation of this idea has been already gained. Nowadays the country develops such projects as innovative centers— Skolkovo, INO Tomsk, Innopolis, and Vorobyovy Gory science and technology valley of Lomonosov Moscow State University.

An ability to generate new knowledge is one of the determining characteristics of a country pursuing leadership in the XXI century. Russia has an infrastructure relevant for such generation: today 188 shared knowledge centers, 146 unique research units, 16 supercomputer centers operate in the country. The Russian Federation actively participates in a number of breakthrough international research projects, for instance, in the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN).

The results of the Universities as Centers of Creating Innovation Areas program by 2025

- over 100 university centers of the regions’ innovative, technological and social development are established in Russia;

- at least ten leading Russian universities are ranked in the top 100 of the world university rankings.

For more information on the status and development of the innovative system of the Russian Federation refer to here .

At the same time the Megascience infrastructure is being established in the territory of the Russian Federation. It involves joint international projects such as IGNITOR—construction of an experimental nuclear fusion reactor; PIK—building of a high flux reactor for the International Center of Neutron Characterization; NICA—construction of a proton and heavy ion collider, etc.

The Strategy of Research and Technological Development also focuses on establishing world-class research megaunits in the territory of Russia. The Russian Megascience projects are considered as one of efficient ways both of attracting international researchers to Russia and of Russia’s integration into the global science. Thus, currently 30 countries participate in the NICA project, the collider is expected to be launched in 2020.

In the fall of 2017 the Russian researchers will make first experiments on the European x-ray free electron laser—European XFEL—in Hamburg. Twelve countries participated in designing, constructing and equipping this Megascience unique research unit, Russia became one of the largest XFEL investors, beside Germany. For more information on Russia’s Strategy of Research and Technological Development refer to here ; on Russia’s participation in Megascience and the project initiatives refer to here .

Universities as centers of creating innovation areas. It is the name of a new priority action framework for development in Russian higher education.

The document was approved by the RF Presidential Council on Strategic Development and Priority Projects in the fall of 2016. In fact, the new program continuous the large-scale national project Education as it aims at systematic qualitative changes of Russia’s higher education. The implementation of the project Universities as Centers of Creating Innovation Areas will involve all the leading universities of Russia.

The program is supposed to be implemented in stages during a ten-year period—up to 2025. The milestones for each stage are the quantitative and qualitative changes which should be attained in each program directions by a clearly defined deadline. The overall outcome of this program is the global competitiveness of Russian higher education and the development of the national network of innovative university systems—an effective action force of the country’s overall innovative transformations.

The Annual International Conference of the Asia- Pacific Quality Network (APQN) “New Horizons: Dissolving Boundaries for a Quality Region” will take place in Russia for the first time. Representatives of expert and accreditation agencies, educational institutions and representatives of the Ministries of Education of the Asia-Pacific countries will participate in the Conference hosted by the National Centre for Public Accreditation in Moscow on May 26-27, 2017.

For more information on the APQN Conference in Moscow refer to web-site.

Quality assurance system

The post-Soviet Russia initiated the establishment of the higher education assessment and quality assurance system twenty-five years ago, when the Law on Education of 1992 was enacted. During this period the methodology and criteria of state accreditation of higher education institutions have been elaborated, organizational and legal regulations for accreditation procedures have been developed as well as enormous practical experience of state accreditation has been gained.

In 2012 the new Law on Education entered into force in the Russian Federation. According to this Law, the modern higher education assessment and quality assurance system is represented by state accreditation and professional public accreditation.

The objective of state accreditation is the compliance of an educational program with the Federal State Education Standards (FSESs). Only such compliance entitles educational institutions to award state-recognized degrees. After successful completion of the state accreditation procedure the higher education institution is granted an accreditation certificate which is valid for six years. After this term the HEI is to undergo the relevant accreditation procedures again. A Certificate of State Accreditation of an educational program is an obligatory document to be published by the educational institution on its official website. The executive body authorized to conduct state accreditation of higher education institutions is the Federal Service for Supervision in Education and Science, a structural division of the Ministry of Education and Science of the RF.

Within the past decade the professional public accreditation system was extensively developing in Russia. In contrast to state accreditation, this procedure is voluntary for higher education institutions. Its objective is to reveal significant (advanced) achievements of an educational institution corre sponding to the latest trends of the education, science and manufacturing development in Europe and in the world.

- In 2015 3,439 educational programs from 554 higher education institutions were recognized as the best, it made 13.62% of the total number of programs.

- The percentage analysis of educational programs in the leading universities of the country showed that over 20% of the programs delivered by these universities are popular. Students taking these programs have excellent learning performance.

- According to the specialized Internet survey, the percentage of programs listed in the Best Educational Programs of Innovative Russia in Lomonosov Moscow State University and Saint Petersburg State University was 22.35%; in federal universities 29.8% and in national research universities 22.56%.

Nowadays Russia faces the growth of organizations conducting public accreditation. First of all, it deals with large employers’ associations which include the relevant accreditation councils. In this case accreditation criteria correspond to employers’ requirements to educational institutions: for example, a practical focus of educational programs, effectiveness of cooperation with partner employers, demand for graduates on the labor market, etc. Some time earlier, similar organizations were established within the academic community, too. The three oldest and most reputable players in the Russian academia are the following:

- Accreditation Center of the Association for Engineering Education of Russia, AEER;

- Agency for Quality Assurance in Higher Education and Career Development, AKKORK;

- National Centre for Public Accreditation, NCPA.

It should be noted that the Russian coordinator of this important international meeting is the National Centre for Public Accreditation. NCPA is a full member of such international networks of quality assurance as: the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA); the Central and Eastern European Network of Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (CEE Network); the Asia-Pacific Quality Network (APQN); the International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE). Since 2013 NCPA has been a member of the IREG Observatory on Academic Ranking and Excellence (IREG Observatory); in 2014 NCPA was officially registered in the European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education.

In 2014 the National Centre for Public Accreditation became the coordinator of the Fourth ENQA Members’ Forum which took place in Russia for the first time.

The unique NCPA’s project Best Educational Programs of Innovative Russia is one of the first projects in the country focusing on independent evaluation of higher education quality. The project is not a classical ranking, but selection of best programs without assigning any places or arranging any succession. The project hallmark is assessment of programs as other ranking projects existing in Russia focused on assessment of educational institutions differentiating them according to their profiles and types of legal entity. Such information on educational programs is especially requested by prospective students. It is also useful both for HEI’s administration (from the rector to deans and department chairmen) and for HEI’s divisions such as Quality Management.

Distinct advantages of the project are as follows: its periodicity (implemented annually since 2010), independence (performed by the National Guild of Experts in Higher Education, and by the Accreditation in Education journal, wide public participation (over 2,000 evaluations annually), extended dissemination of results (the reference book Best Educational Programs of Innovative Russia is annually published electronically and in hard copies, in 2014 it was published in English).

Other two nationwide rankings of higher educa tion in Russia are the National University Ranking compiled by Interfax and the Echo Moskvy news agency and the RAEX University Ranking. In addition to it, in 2016 the ranking focusing on effectiveness of the innovative activities performed by the leading Russian universities (namely, the national research universities, the Project 5-100 universities, the federal universities) was published for the first time. The project was implemented by ITMO University and Russian Venture Company (RVC) (for more details refer to web-site).

Summarizing the information of this chapter it should be noted that professional associations and public organizations—employers, academic and expert communities, student associations—are taking a more active and significant part in the establishment and development of the Russian professional education assessment and quality assurance system. However, the significant institutional stakeholder of this system is the state itself. In particular, except state accreditation, in 2012 the government, represented by the Ministry of Education and Science of the RF, initiated the annual monitoring of HEI’s efficiency and the monitoring of training quality in educational institutions delivering programs of secondary vocational education. The information and analytical materials of the monitoring are annually published on the special website and publicly available.

This procedure focuses on revealing and analyzing the compliance of the university activities with the criteria set by the state. The criteria concern the following fields: education, research, international activities, financial and economic activities, academic staff salaries, graduates’ employment, etc. If an educational institution meets less than four out of seven monitoring indicators (i.e. it attained the threshold requirements) then a special inter-institutional commission should be established for elaborating recommendations for the founders of an ineffective educational institution. In each case recommendations can vary; they may contain measures for optimization of a HEI’s activities or, as an extreme measure, a proposal for HEI’s liquidation. Thus, the annual monitoring is a tool for operative analysis of higher education and vocational education institutions in Russia and for eliminating a low quality sector, if necessary.

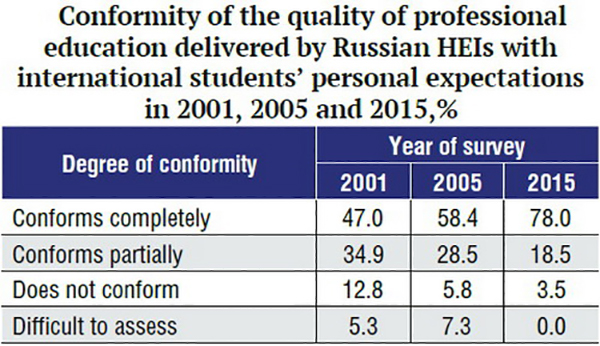

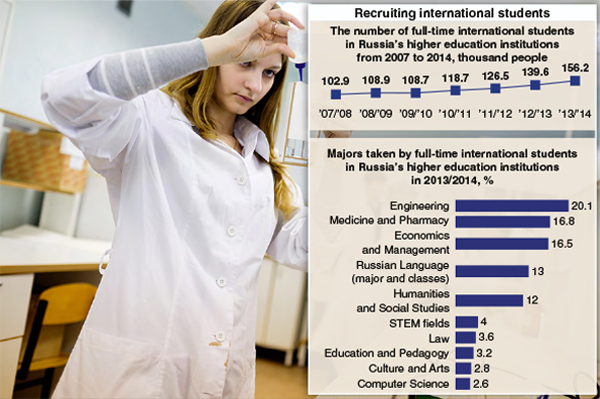

From 2007 to 2017 the number of international students in Russia has increased from 102.9 thousand up to 156.2 thousand people. According to the survey among international students, the number of responses that the quality of education delivered by Russian universities completely conformed to their personal expectations increased from 47% in 2001 up to 78% in 2015.

Higher education in Russia: international dimension

The measures taken within the past decade and aimed at the modernization and quality improvement of higher education have already resulted in some positive outcomes. It is proved by the increased number of Russian universities presented in different world education rankings as well as by improving their ranking positions in comparison with the previous ranking surveys (for more information on this topic refer to the article “Rankings: the Leadership Race” in this issue). Nowadays the Project 5-100 is initiated and being implemented in Russia; its goal is the targeted state support of the leading Russian universities’ competitiveness and their promotion in the global education area ( here ).

An additional way of integration of Russian higher education with international partner universities is the establishment of network universities:

- BRICS Network University;

- University SCO (the Shanghai Cooperation Organization);

- the Commonwealth of Independent States Network University.

The significant state project promoting the integration academic processes is the Megagrant Program. The Minister of Education and Science of the RF Olga Vasilyeva called this program “Russia’s business card for international cooperation in science and technology.” The program initiated in 2010 will be in progress until 2020. Its goal is the establishment of the world-class research laboratories on the base of Russian universities and research centers as well as the development of advanced scientific schools and research teams. The objective of research laboratories is breakthrough fundamental and applied research, the outcomes of which can be used in the real economy.

Grants are awarded to those who intend to implement their ideas in this country together with Russian expert teams. The grantees are leading international and Russian scientists, Russian citizens working abroad at the moment. From 2010 to 2016 five Megagrant contests took place, they aroused great interest of the global research community. All in all during this time scientists from 45 countries submitted almost 3,000 applications. All the submitted projects are considered in accordance with international standards. Eventually, 78 foreign and 82 Russian scientists (including 57 researchers living abroad) became the program finalists. The program winner lists include five Nobel laureates, Fields Medalists, Humboldt Prize winners, and other prestigious prize holders.

The establishment of up-to-date environment for life and professional activities as well as most favored conditions for study and research is the main ground which can make Russia a country attracting international researchers, educators, and students. Definitely, it is a large-scale task, and its solution is a long-term project by itself. Not only for selected universities, but also for

the country—society and the state—as a whole. Will Russia meet this challenge? Let statistics show.

Nowadays within the Megagrant Program 200 world-class research laboratories in the fields of machine building, space exploration, new technology creation, medical product development, diagnostics and treatment, and others are established on the base of the leading Russian universities and research centers.

Over 50% of laboratory staff are young researchers under 35.

- Society ›

Education & Science

Education in Russia - statistics & facts

General education in russia, higher education in russia, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Expected average length of education in Russia 2000-2021

Government spending on education as a GDP share in Russia 2010-2021

PISA ranking of Russia 2015-2018, by category

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Government spending on education in Russia 2022, by level

Number of higher education students in Russia 2010-2022

Educational Institutions & Market

Highest earning EdTech platforms in Russia 2023

Related topics

Recommended.

- Online education in Russia

- Education in Poland

- Education in Romania

Recommended statistics

- Premium Statistic Education consumer spending in Europe 2020, by country

- Premium Statistic Number of universities worldwide in 2023, by country

- Premium Statistic Trust in teachers worldwide 2022, by country

- Basic Statistic PISA results in Russia 2006-2018, by category

Education consumer spending in Europe 2020, by country

Ranking of the total consumer spending on education in Europe by country 2020 (in million U.S. dollars)

Number of universities worldwide in 2023, by country

Estimated number of universities worldwide as of July 2023, by country

Trust in teachers worldwide 2022, by country

Trust in teachers as of 2022, by country

PISA results in Russia 2006-2018, by category

Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results in Russia from 2006 to 2018, by category (in points)

Education spending

- Basic Statistic Government spending on education as a GDP share in Russia 2010-2021

- Basic Statistic Government spending on education in Russia 2022, by level

- Basic Statistic Public education spending per student in Russia 2022, by segment

- Basic Statistic Average consumer prices on education services in Russia 2022

- Premium Statistic Average university tuition in selected regions of Russia 2020

- Basic Statistic Estimated education costs in Russia 2020, by city

Share of government expenditure on education in gross domestic product (GDP) in Russia from 2010 to 2021

Government expenditure on education in Russia in 2022, by segment (in billion Russian rubles)

Public education spending per student in Russia 2022, by segment

Government expenditure on education per student in Russia in 2022, by stage (in 1,000 Russian rubles)

Average consumer prices on education services in Russia 2022

Average consumer prices on selected types of education services in Russia in 2022 (in Russian rubles)

Average university tuition in selected regions of Russia 2020

Average annual tuition fee at higher education institutions in Russia in 2020, by selected federal subject (in 1,000 Russian rubles)

Estimated education costs in Russia 2020, by city

Estimated cost of the entire educational cycle from early childhood to completion of higher education in Russia in 2020, by city (in million Russian rubles)

Preschool & general education

- Premium Statistic Children enrolled in preschool education in Russia 2015-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of school students in Russia 2021, by educational stage

- Basic Statistic Number of school students in Russia 2015-2022, by type of area

- Basic Statistic Unified State Exam average score in Russia 2022, by subject

Children enrolled in preschool education in Russia 2015-2022

Number of children enrolled in preschool institutions in Russia from 2015 to 2022 (in millions)

Number of school students in Russia 2021, by educational stage

Number of students enrolled in general education institutions in Russia as of the beginning of school year 2021/2022, by stage (in 1,000s)

Number of school students in Russia 2015-2022, by type of area

Number of students in state (municipal) schools in Russia from school year 2015/2016 to 2022/2023, by type of area (in millions)

Unified State Exam average score in Russia 2022, by subject

Average score in the Unified State Exam achieved by high school graduates in Russia in 2022, by subject (in points)

Vocational & higher education

- Basic Statistic Professional education admission in Russia 2016-2020, by level

- Basic Statistic Vocational education student count in Russia 2016-2021

- Premium Statistic Number of higher education students in Russia 2010-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of university students in Russia 2014-2022, by degree

- Basic Statistic Number of university students in Russia 2022, by gender and age

- Premium Statistic Number of doctoral students in Russia 2010-2021

- Premium Statistic University admission share in Russia 2017-2020, by funding type

- Basic Statistic Leading Russian universities by QS ranking 2023

Professional education admission in Russia 2016-2020, by level

Admission to professional education institutions in Russia from 2016 to 2020, by type (in 1,000s)

Vocational education student count in Russia 2016-2021

Number of students enrolled in vocational education programs in Russia from school year 2016/2017 to 2021/2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of students enrolled in higher education in Russia from 2010 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of university students in Russia 2014-2022, by degree

Number of students enrolled in higher education institutions in Russia from academic year 2014/2015 to 2022/2023, by degree (in 1,000s)

Number of university students in Russia 2022, by gender and age

Number of higher education students in Russia in academic year 2022/2023, by age and gender

Number of doctoral students in Russia 2010-2021

Number of doctoral students in Russia from 2010 to 2021 (in 1,000s)

University admission share in Russia 2017-2020, by funding type

Distribution of admissions into higher education institutions in Russia from 2017 to 2020, by tuition funding type

Leading Russian universities by QS ranking 2023

Leading universities in Russia by rank in the QS World University Rankings 2023

International students

- Premium Statistic Top host destination of international students worldwide 2022

- Premium Statistic International student share of higher-ed population worldwide in 2022, by country

- Premium Statistic Field of study of international students worldwide 2022, by country

- Premium Statistic Share of foreign university students in Russia 2021/2022, by country

- Premium Statistic Foreign doctoral student count in Russia 2014-2021

- Basic Statistic Best cities for studying abroad in Russia 2022

Top host destination of international students worldwide 2022

Top host destination of international students worldwide in 2022, by number of students

International student share of higher-ed population worldwide in 2022, by country

Countries with the largest amount of international students as a share of the total higher education population in 2022

Field of study of international students worldwide 2022, by country

Field of study of international students worldwide in 2022, by country

Share of foreign university students in Russia 2021/2022, by country

Share of international students enrolled in bachelor's, specialist's, and master's programs in higher education institutions in Russia in school year 2021/2022, by country of origin

Foreign doctoral student count in Russia 2014-2021

Number of foreign doctoral students in Russia from 2014 to 2021 (in 1,000s)

Best cities for studying abroad in Russia 2022

Leading cities for studying abroad in Russia by score in the QS Best Student Cities ranking 2022 (in points)

Institutions & infrastructure

- Basic Statistic Capacity of preschool organizations in Russia 2015-2021

- Basic Statistic General education institution count in Russia 2014-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of village schools in Russia 2010-2022, by ownership

- Premium Statistic University count in selected regions of Russia 2020

Capacity of preschool organizations in Russia 2015-2021

Number of places at preschool education, supervision, and childcare institutions per 1,000 children aged 1-6 years in Russia from 2015 to 2021

General education institution count in Russia 2014-2022

Number of primary, basic general, and general secondary education institutions in Russia from school year 2014/2015 to 2022/2023 (in 1,000s)

Number of village schools in Russia 2010-2022, by ownership

Number of state (municipal) and private schools in rural areas in Russia from school year 2010/2011 to 2022/2023

University count in selected regions of Russia 2020

Number of higher education institutions in Russia in 2020, by selected federal subject

Teaching personnel

- Basic Statistic Number of teachers in Russia 2022, by educational stage

- Basic Statistic School teacher count in Russia 2022, by specialization

- Basic Statistic University employee age distribution in Russia 2022, by position

- Basic Statistic Monthly salary of teachers in Russia 2022, by education segment

Number of teachers in Russia 2022, by educational stage

Number of teaching personnel in education system in Russia in 2022, by segment (n 1,000s)

School teacher count in Russia 2022, by specialization

Number of school teachers in schools in Russia in school year 2022/2023, by specialization

University employee age distribution in Russia 2022, by position

Distribution of higher education employees in Russia in school year 2022/2023, by age group and position

Monthly salary of teachers in Russia 2022, by education segment

Average monthly salary of teaching personnel in Russia in 2022, by educational stage (In Russian rubles)

- Premium Statistic B2C online education market size in Russia 2019-2023

- Basic Statistic Online education market value in Russia 2021, by stage

- Premium Statistic Online education market share in Russia 2021, by segment

- Premium Statistic Highest earning EdTech platforms in Russia 2023

B2C online education market size in Russia 2019-2023

Market volume of B2C online education in Russia from 2019 with a forecast until 2023 (in billion Russian rubles)

Online education market value in Russia 2021, by stage

Estimated revenue of online education in Russia in 2021, by stage (in billion Russian rubles)

Online education market share in Russia 2021, by segment

Estimated share of online in the education market revenue in Russia in 2021, by segment

Leading EdTech platforms in Russia in 3rd quarter 2023, by revenue (in billion Russian rubles)

Public opinion

- Basic Statistic Public assessment of education system in Russia 2021

- Basic Statistic Attitude toward the Unified State Exam in Russia 2009-2023

- Basic Statistic Most popular university major choices in Russia 2020, by gender

- Basic Statistic Factors influencing university major choice in Russia 2020/2021

- Basic Statistic Factors affecting university choice in Russia 2020/2021

Public assessment of education system in Russia 2021

How would you assess the state of our education system?

Attitude toward the Unified State Exam in Russia 2009-2023

What is your opinion on the modern schoolchildren's certification system, the Unified State Exam?

Most popular university major choices in Russia 2020, by gender

Leading fields of study at the university preferred by high school graduates in Russia 2020, by gender

Factors influencing university major choice in Russia 2020/2021

Factors considered by students when choosing a university major in Russia in the academic year 2020/2021

Factors affecting university choice in Russia 2020/2021

Main factors taken into account by students when selecting a university in Russia in the academic year 2020/2021

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

- Education in Europe

- Education in Germany

- Education worldwide

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

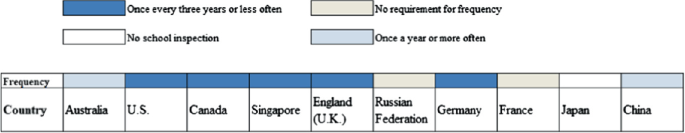

Global Comparison of Education Systems

- Open Access

- First Online: 02 January 2024

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Ziyin Xiong 4

2262 Accesses

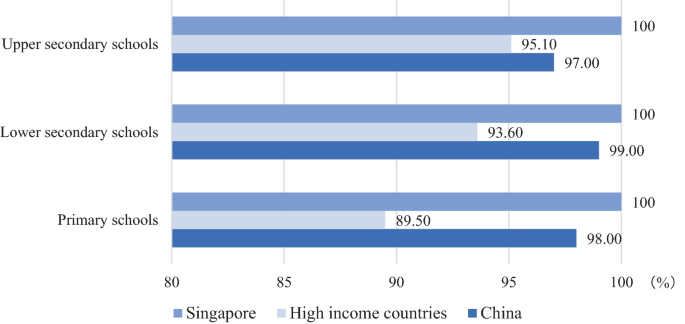

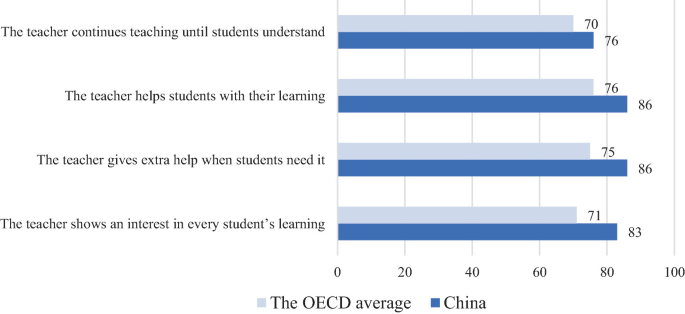

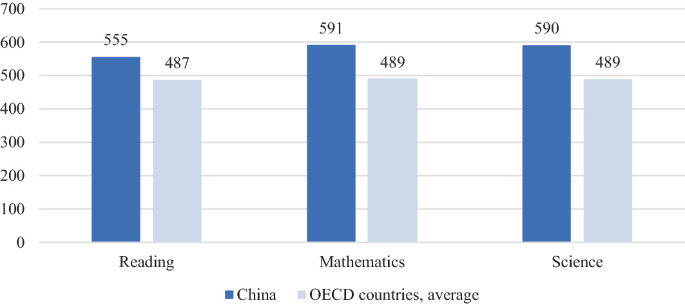

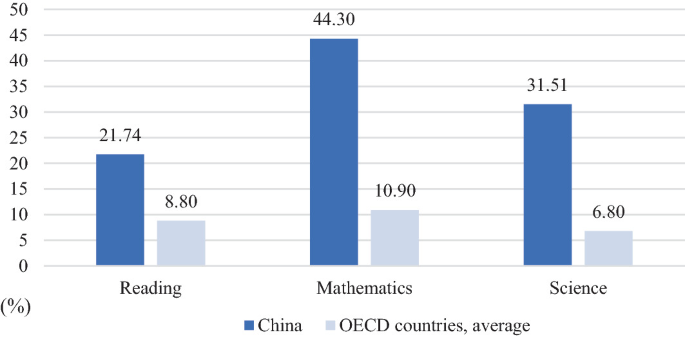

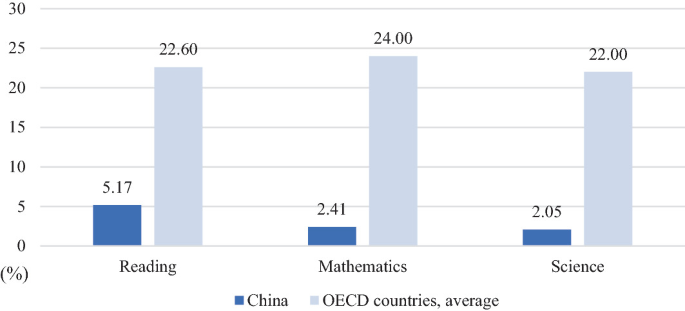

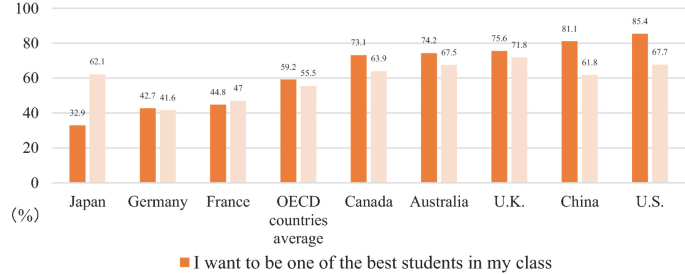

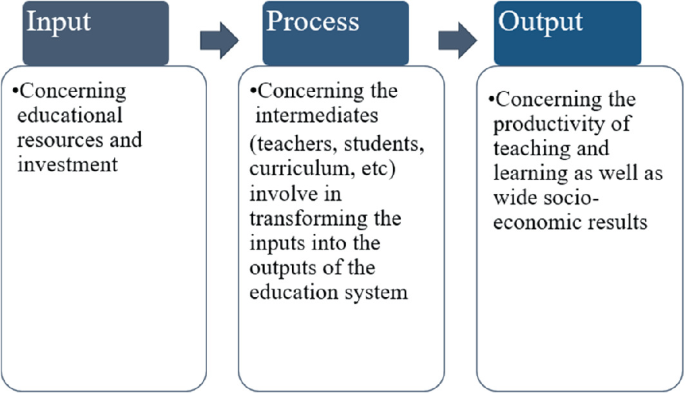

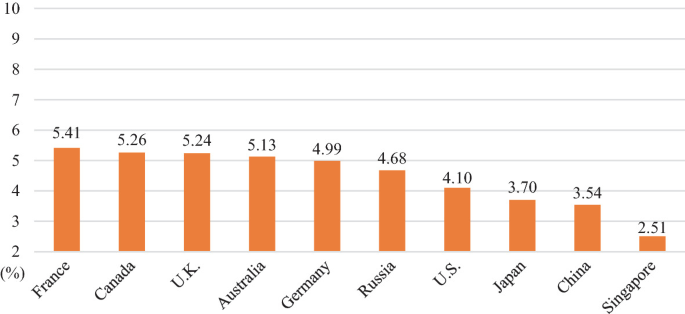

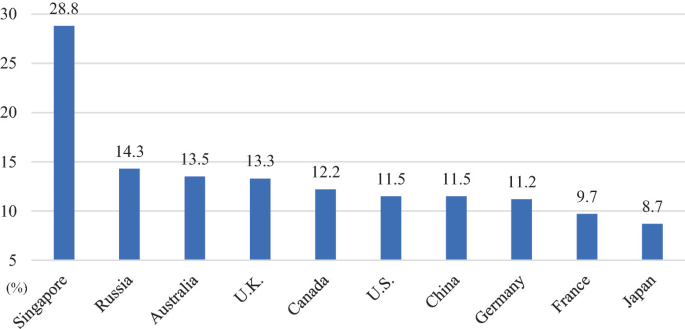

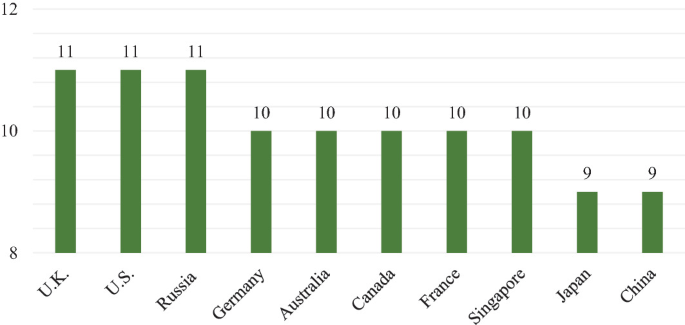

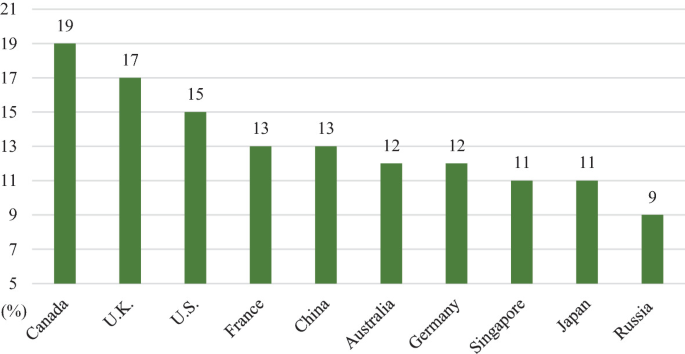

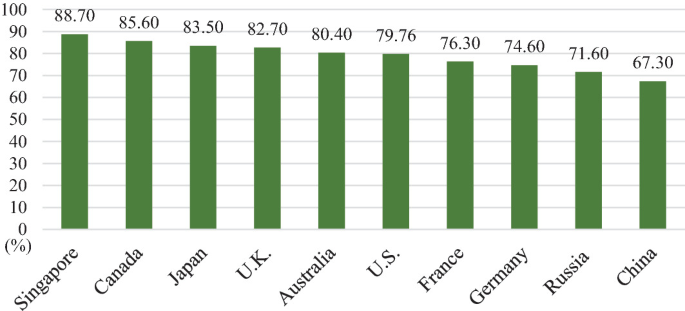

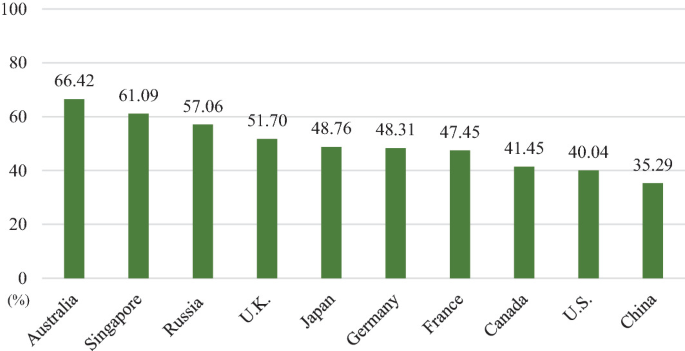

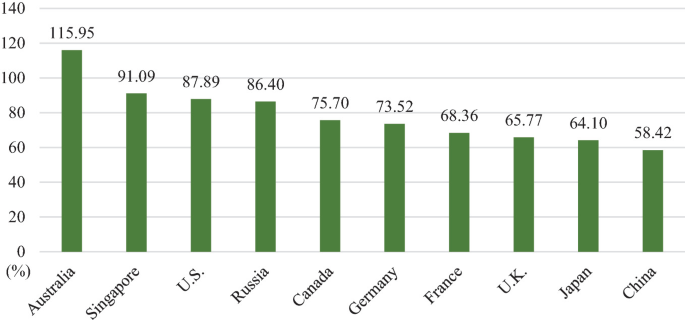

This chapter combines the quantitative data with the rich qualitative evidence and triangulates the diverse evidence to systematically unearth themes and provide an in-depth review of China’s dynamic education system. This chapter not only presents a benchmark study showing how China’s education systems perform vis-a-vis other national education systems, but also probes into the policies and practices to reveal the contextual factors contributing to the unique patterns of China’s education system.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Comparing Systems

Education Systems in South Asia: An Introduction

How can education systems improve? A systematic literature review

- Education system

- Comparative education

- Education quality

1 Introduction

From a global perspective, this chapter examines education systems at a national level. The concept of education systems borrows the idea of “system” from a broad definition in social science, which refers to a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole (Backlund, 2000 ). In the sphere of education, the idea of education systems typically encompasses all the elements involved in education, such as funding, facilities, staffing, curriculum, pedagogy, regulations, and policies. These elements are interrelated and organized strategically to achieve overarching educational goals. In other words, using the term “education system” aims to deconstruct the complex and multifaceted nature of education. By doing so, this chapter is able to present an overall and comparative view of the education systems in selected countries.

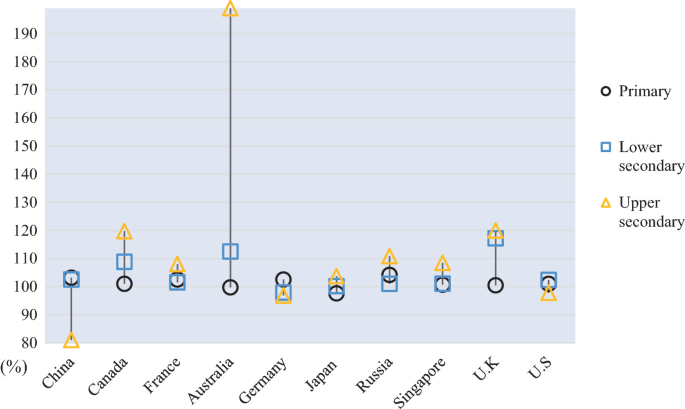

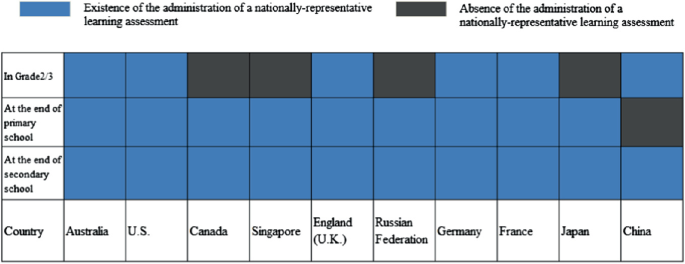

Based on the acknowledgment that students’ learning pathways vary among countries and regions, this chapter begins with a brief introduction of the education systems in selected countries, including Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, Singapore, the United Kingdom (U.K.) and the United States (U.S.). The learning pathways serve as the foundation of the education systems, which determine when students start their education, what academic tracks students can choose, and how students can move vertically or horizontally to achieve their education goals. A well-designed education system provides flexible learning pathways for its learners and avoid potential social segregation (OECD, 2020 ).

This chapter reviews the learning pathways of education systems at the basic education level by referring to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). ISCED, developed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which provides a common framework to benchmark education systems across nations (UNESCO Institute for Statistics [UIS], 2012). This chapter adopts the ISCED 2011 classification to present the learning pathways in each nation. The scope of this chapter covers only the basic education level which includes elementary education (ISCED 1), lower secondary education and upper secondary education (see Table 1 ). While a snapshot of the learning pathway is provided, the distinctive features embedded in these education systems are also highlighted.

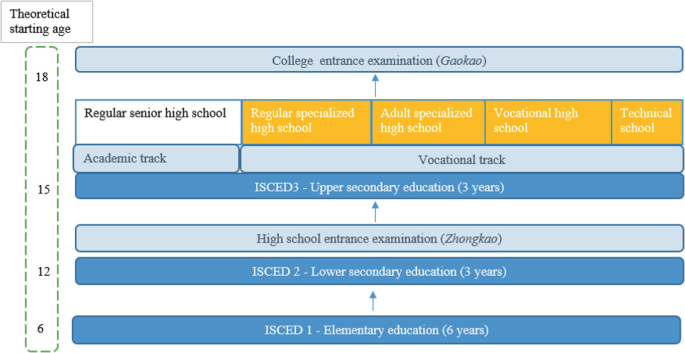

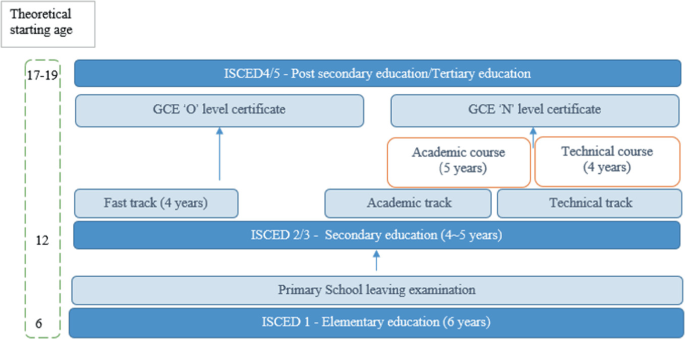

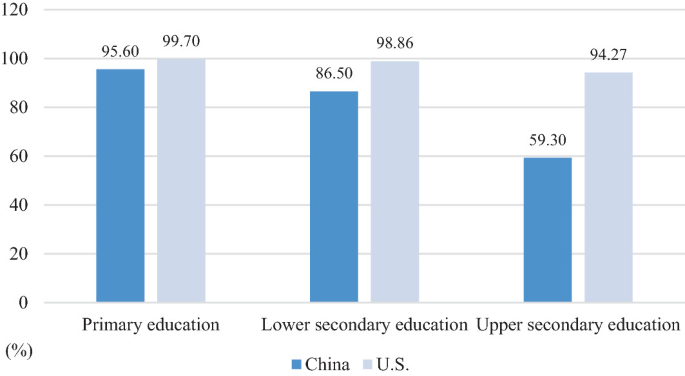

The People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) has the world’s largest population of school-aged children. Its education system accommodates over 291 million students with more than 18 million teachers serving in 520,000 schools (excluding private education) (Ministry of Education [MOE], 2022 ). In 1986, the Chinese government regulated nine-year compulsory education in its legal framework, with the aim to provide elementary education and lower secondary education to every child in the country.

After completing nine-year compulsory education, students can choose from two distinctive learning tracks provided. One is the academic track and the other is the vocational track. On the vocational track, there are four major types of schooling available, including regular specialized high schools, adult specialized high schools, vocational high schools, and technical schools. One of the major distinctions among them is the difference in the governance bodies and the institutes issuing the certificates. Among the four programs, regular specialized high schools tend to be the mainstream one, which attracts most vocational students. However, compared with the academic track, the vocational track is overall less attractive to Chinese students and their parents (Fig. 1 ).

The education system in China

1.2 The U.K. (England Only)

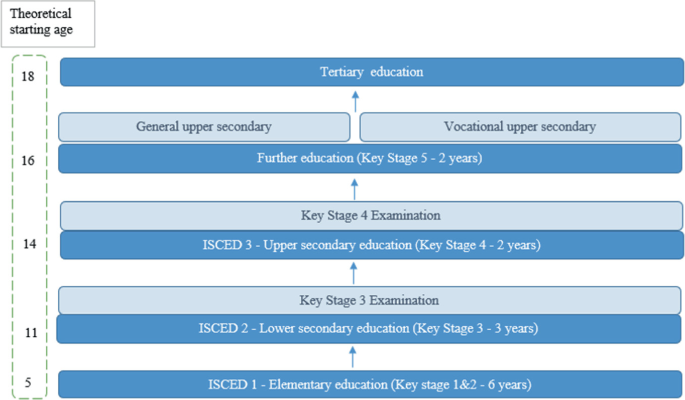

The education system in the United Kingdom (U.K.) is a devolved matter with each of the jurisdictions having separate systems overseen by separate governments. The U.K. government is responsible for the education system in England, whereas education systems in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are governed by their respective governments. This section only discusses the education system in England.

England also has a tradition of independent schools and home education. In England, the learning tracks in the state-funded education system are categorized into “key stages” based upon age. It begins with Early Years Foundation Stage (aged 3 to 4). Elementary education (aged 5 to 10) is subdivided into Key Stage 1 (aged 5 to 6) and Key Stage 2 (Juniors, aged 7 to 10). Secondary education (aged 11 to 15) is further split up into Key Stage 3 (aged 11 to 13) and Key Stage 4 (aged 14 to 15). Above Key Stage 4 is the post-16 education (ages 16 to 17) and tertiary education (aged over 18). The law has legitimized the compulsory education for all children under 18 years old. Unlike some countries where there is a clear boundary between lower secondary education and higher secondary education, England unifies the two education levels and organizes them as an integrated whole. In the final two years of secondary education (normally at the age of 15 or 16), students typically take a General Certificate of Secondary Education exams (GCSE) or other Level 1 or Level 2 Footnote 1 certificates of which the result is important for those students in pursuit of further academic qualifications. The division of academic and vocational tracks normally takes places after the completion of secondary education ( education is compulsory until 18, but schooling is compulsory to 16, so post-16 education can be academic or vocational). In terms of higher education, students in England often start with a three-year bachelor’s degree followed by postgraduate studies (Fig. 2 ).

The education system in England

1.3 The U.S

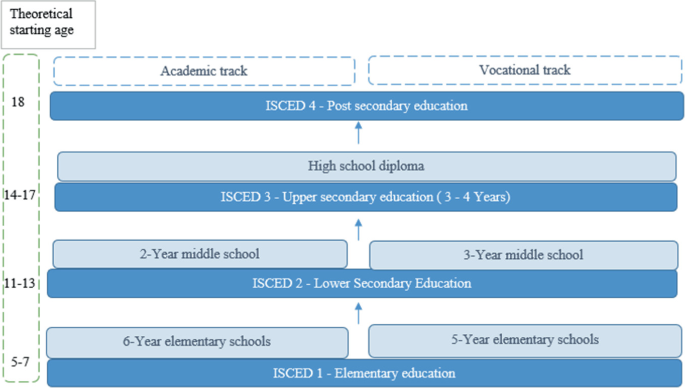

The U.S. adopts a decentralized approach to organize its education system. Education systems adopt various forms across each state. Biggest changes at the state-level include funding, policy, curriculum, and licensing – the overall structure is very similar nationally. While differences exist across the states, this section intends to provide information and common features of how education at the basic level is organized in the U.S.

The age for starting schooling is between five to seven, depending on each state’s regulations. The number of years for compulsory education also vary among states. Around 30 out of 50 states promote 11-year compulsory education. It is worth mentioning that although 11-years are compulsory, basic education typically comprises 13 years of education (K-12). Unlike some countries where there is a clear distinction between the academic track and the vocational track, the U.S. tends to integrate the two tracks into general secondary schools. Instead of providing vocational-oriented schools, the education system in the U.S. tends to spread out the vocational-oriented courses through the academic learning during secondary education. The intention is to broaden students’ learning experiences, cultivate students’ career interests through a wide spectrum of vocational and academic oriented courses (Fig. 3 ).

The education system in the U.S

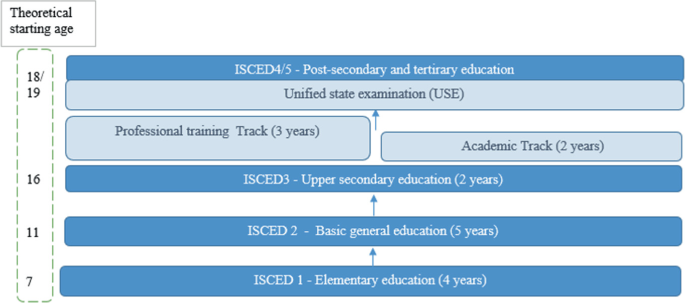

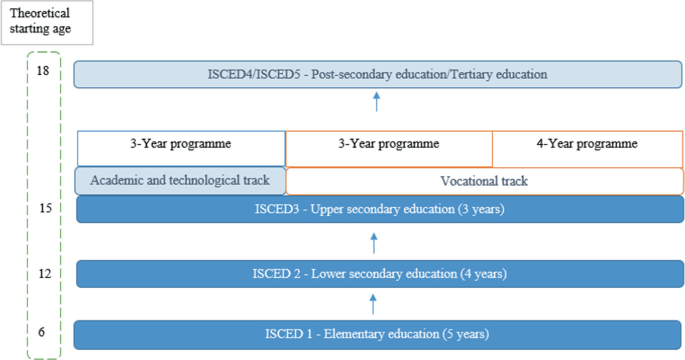

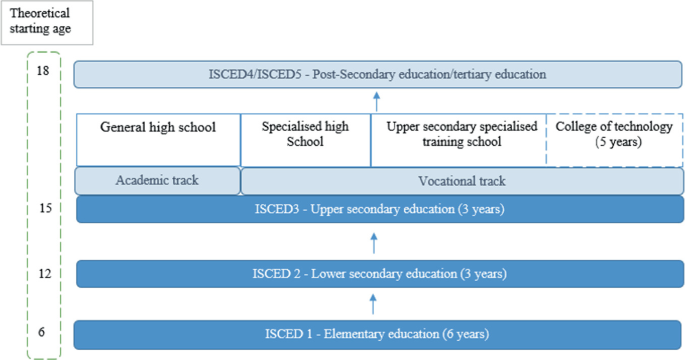

Education services in Russia are regulated by the Ministry of Education and Science. Russia offers a relatively long compulsory education period, which is 11 years including four years of elementary education, five years of basic general education (equivalent to lower secondary education) and two years of upper secondary education. Children must attend school when they reach the age of seven. The boundary between elementary education and lower secondary education is not clear. Typically, state-run schools offer both education levels to students.

Learning tracks split at the upper secondary education level. The general learning track offers students a two-year academic-oriented education program. Once students complete the general upper secondary education, they are obliged to pass the unified state examination (USE). Math and Russian language are compulsory exam subjects, whereas other subjects are up to students to select other exam subjects to align with university-specific admissions standards. Another track at the upper secondary education level is the vocational training track, which offers a three-year long vocational education program (Fig. 4 ).

The education system in Russia

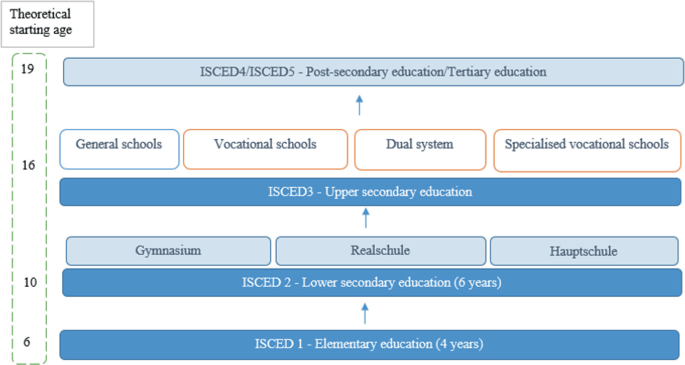

1.5 Germany

In Germany, once children reach the age of six, they are obliged to attend elementary and secondary education in Germany. Compulsory education includes four years’ elementary schooling and six years’ lower secondary schooling. The division between academic-oriented track and vocational-oriented track begins after the completion of elementary education.

There are various lower secondary schools available in Germany’s education system. The typical ones are namely, Gymnasium (Academic oriented school), Hauptschule (vocational oriented school) and Realschule (comprehensive lower secondary school). Gymnasium represents the general track, which emphasizes academic learning and requires high marks for admissions when compared with the other two schools. Hauptschule offers schooling to young students whose grades are average or below. There are academic subjects offered to students, but the curriculum and content are adjusted to the level of Huaptschule students. In addition, Work Studies are included in the Hauptschulen curriculum but not in the Gymnasium curriculum. Realschule is another type of lower secondary school, which ranks between Hauptschule and Gymnasium in terms of academic requirement for admission. Realschule offers an extensive education service that prepares students to pursue both vocational learning and academic learning in the future (Kotthoff, 2011 ).

One of the well-known strengths in Germany’s education system is that the dual system exists in German vocational schools. The dual system combines apprenticeships at company and vocational education at schools as an integrated program. Germany published the vocational training act which provides a common standard and framework to regulate the dual systems in Germany. The dual system has yielded positive educational results. For example, during the 2008 economic crisis, young German people are more resilient in the labor market than their peers in other OECD countries (Kuczera & Field, 2010 ) (Fig. 5 ).

The education system in Germany

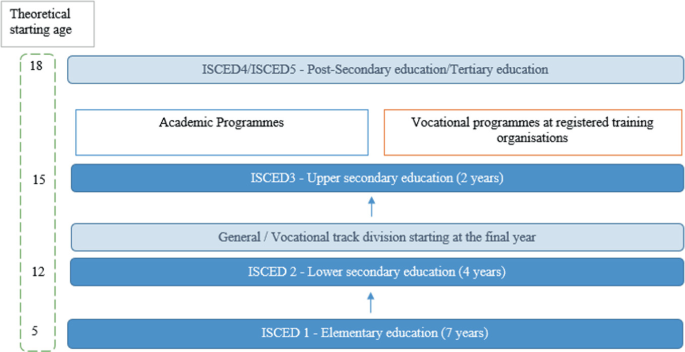

1.6 Australia

Compulsory education in Australia typically lasts for 12 years, which is longer than many education systems introduced in this chapter. The starting age varies between the ages of 4 and 6 and the education lasts until the ages of 15, 16 and 17, depending on the state or territory.

The learning track typically diverges in the final year of the lower secondary education. Students who intend to follow the vocational learning track enroll in further courses at registered training organizations (RTOs) once they complete lower secondary education. RTOs typically provide vocational education services under the direction of the national government. RTOs include both government-owned institutes and private colleges. Vocational education track has a clear qualification framework regulated at the national level, which provides pathways for vocational education students who intend to enter the higher education pathway. Students who obtained certain levels of qualification (e.g., diploma level and advanced diploma level) are allowed to enter higher education (Fig. 6 ).

The education system in Australia

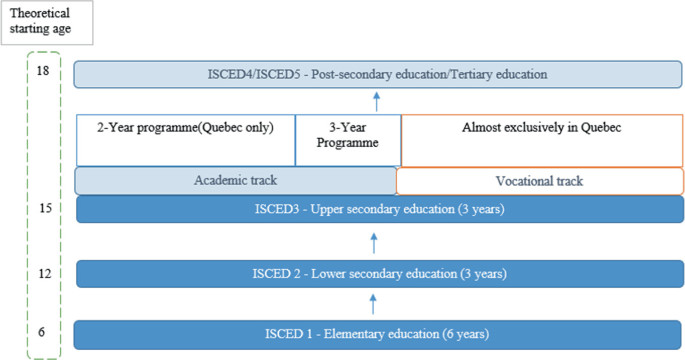

Education is governed by the provincial, territorial, and local governments in Canada. The education system is mainly regulated by provincial jurisdiction and each province also oversees the curriculum. Despite differences across the provinces, the education systems in Canada still have some similar features in its structure (Fig. 7 ).

The education system in Canada