If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- Introduction to the Civil Rights Movement

- African American veterans and the Civil Rights Movement

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- Emmett Till

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

- "Massive Resistance" and the Little Rock Nine

- The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

- SNCC and CORE

- Black Power

- The Civil Rights Movement

- On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks , a black seamstress, was arrested in Montgomery, Alabama for refusing to give up her bus seat so that white passengers could sit in it.

- Rosa Parks’s arrest sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott , during which the black citizens of Montgomery refused to ride the city’s buses in protest over the bus system’s policy of racial segregation. It was the first mass-action of the modern civil rights era, and served as an inspiration to other civil rights activists across the nation.

- Martin Luther King, Jr. , a Baptist minister who endorsed nonviolent civil disobedience, emerged as leader of the Boycott.

- Following a November 1956 ruling by the Supreme Court that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional, the bus boycott ended successfully. It had lasted 381 days.

Rosa Parks’s arrest

Origins of the bus boycott, the boycott succeeds, what do you think.

- William H. Chafe, The Unfinished Journey: America Since World War II , eighth edition (New York: Oxford U.P., 2015), 153-154. For the details of her arrest see, “Police Department, City of Montgomery—Rosa Parks Arrest Report,” December 1, 1955.

- See James Patterson, *Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 400; Davis Houck, and Matthew Grindy, Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), x.

- See Patterson, Grand Expectations , 400-401.

- Patterson, Grand Expectations , 405.

- Quoted in Chafe, The Unfinished Journey , 156.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Montgomery Bus Boycott

December 5, 1955 to December 20, 1956

Sparked by the arrest of Rosa Parks on 1 December 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott was a 13-month mass protest that ended with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that segregation on public buses is unconstitutional. The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) coordinated the boycott, and its president, Martin Luther King, Jr., became a prominent civil rights leader as international attention focused on Montgomery. The bus boycott demonstrated the potential for nonviolent mass protest to successfully challenge racial segregation and served as an example for other southern campaigns that followed. In Stride Toward Freedom , King’s 1958 memoir of the boycott, he declared the real meaning of the Montgomery bus boycott to be the power of a growing self-respect to animate the struggle for civil rights.

The roots of the bus boycott began years before the arrest of Rosa Parks. The Women’s Political Council (WPC), a group of black professionals founded in 1946, had already turned their attention to Jim Crow practices on the Montgomery city buses. In a meeting with Mayor W. A. Gayle in March 1954, the council's members outlined the changes they sought for Montgomery’s bus system: no one standing over empty seats; a decree that black individuals not be made to pay at the front of the bus and enter from the rear; and a policy that would require buses to stop at every corner in black residential areas, as they did in white communities. When the meeting failed to produce any meaningful change, WPC president Jo Ann Robinson reiterated the council’s requests in a 21 May letter to Mayor Gayle, telling him, “There has been talk from twenty-five or more local organizations of planning a city-wide boycott of buses” (“A Letter from the Women’s Political Council”).

A year after the WPC’s meeting with Mayor Gayle, a 15-year-old named Claudette Colvin was arrested for challenging segregation on a Montgomery bus. Seven months later, 18-year-old Mary Louise Smith was arrested for refusing to yield her seat to a white passenger. Neither arrest, however, mobilized Montgomery’s black community like that of Rosa Parks later that year.

King recalled in his memoir that “Mrs. Parks was ideal for the role assigned to her by history,” and because “her character was impeccable and her dedication deep-rooted” she was “one of the most respected people in the Negro community” (King, 44). Robinson and the WPC responded to Parks’ arrest by calling for a one-day protest of the city’s buses on 5 December 1955. Robinson prepared a series of leaflets at Alabama State College and organized groups to distribute them throughout the black community. Meanwhile, after securing bail for Parks with Clifford and Virginia Durr , E. D. Nixon , past leader of the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), began to call local black leaders, including Ralph Abernathy and King, to organize a planning meeting. On 2 December, black ministers and leaders met at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and agreed to publicize the 5 December boycott. The planned protest received unexpected publicity in the weekend newspapers and in radio and television reports.

On 5 December, 90 percent of Montgomery’s black citizens stayed off the buses. That afternoon, the city’s ministers and leaders met to discuss the possibility of extending the boycott into a long-term campaign. During this meeting the MIA was formed, and King was elected president. Parks recalled: “The advantage of having Dr. King as president was that he was so new to Montgomery and to civil rights work that he hadn’t been there long enough to make any strong friends or enemies” (Parks, 136).

That evening, at a mass meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church , the MIA voted to continue the boycott. King spoke to several thousand people at the meeting: “I want it to be known that we’re going to work with grim and bold determination to gain justice on the buses in this city. And we are not wrong.… If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong” ( Papers 3:73 ). After unsuccessful talks with city commissioners and bus company officials, on 8 December the MIA issued a formal list of demands: courteous treatment by bus operators; first-come, first-served seating for all, with blacks seating from the rear and whites from the front; and black bus operators on predominately black routes.

The demands were not met, and Montgomery’s black residents stayed off the buses through 1956, despite efforts by city officials and white citizens to defeat the boycott. After the city began to penalize black taxi drivers for aiding the boycotters, the MIA organized a carpool. Following the advice of T. J. Jemison , who had organized a carpool during a 1953 bus boycott in Baton Rouge, the MIA developed an intricate carpool system of about 300 cars. Robert Hughes and others from the Alabama Council for Human Relations organized meetings between the MIA and city officials, but no agreements were reached.

In early 1956, the homes of King and E. D. Nixon were bombed. King was able to calm the crowd that gathered at his home by declaring: “Be calm as I and my family are. We are not hurt and remember that if anything happens to me, there will be others to take my place” ( Papers 3:115 ). City officials obtained injunctions against the boycott in February 1956, and indicted over 80 boycott leaders under a 1921 law prohibiting conspiracies that interfered with lawful business. King was tried and convicted on the charge and ordered to pay $500 or serve 386 days in jail in the case State of Alabama v. M. L. King, Jr. Despite this resistance, the boycott continued.

Although most of the publicity about the protest was centered on the actions of black ministers, women played crucial roles in the success of the boycott. Women such as Robinson, Johnnie Carr , and Irene West sustained the MIA committees and volunteer networks. Mary Fair Burks of the WPC also attributed the success of the boycott to “the nameless cooks and maids who walked endless miles for a year to bring about the breach in the walls of segregation” (Burks, “Trailblazers,” 82). In his memoir, King quotes an elderly woman who proclaimed that she had joined the boycott not for her own benefit but for the good of her children and grandchildren (King, 78).

National coverage of the boycott and King’s trial resulted in support from people outside Montgomery. In early 1956 veteran pacifists Bayard Rustin and Glenn E. Smiley visited Montgomery and offered King advice on the application of Gandhian techniques and nonviolence to American race relations. Rustin, Ella Baker , and Stanley Levison founded In Friendship to raise funds in the North for southern civil rights efforts, including the bus boycott. King absorbed ideas from these proponents of nonviolent direct action and crafted his own syntheses of Gandhian principles of nonviolence. He said: “Christ showed us the way, and Gandhi in India showed it could work” (Rowland, “2,500 Here Hail”). Other followers of Gandhian ideas such as Richard Gregg , William Stuart Nelson , and Homer Jack wrote the MIA offering support.

On 5 June 1956, the federal district court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that bus segregation was unconstitutional, and in November 1956 the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed Browder v. Gayle and struck down laws requiring segregated seating on public buses. The court’s decision came the same day that King and the MIA were in circuit court challenging an injunction against the MIA carpools. Resolved not to end the boycott until the order to desegregate the buses actually arrived in Montgomery, the MIA operated without the carpool system for a month. The Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s ruling, and on 20 December 1956 King called for the end of the boycott; the community agreed. The next morning, he boarded an integrated bus with Ralph Abernathy, E. D. Nixon, and Glenn Smiley. King said of the bus boycott: “We came to see that, in the long run, it is more honorable to walk in dignity than ride in humiliation. So … we decided to substitute tired feet for tired souls, and walk the streets of Montgomery” ( Papers 3:486 ). King’s role in the bus boycott garnered international attention, and the MIA’s tactics of combining mass nonviolent protest with Christian ethics became the model for challenging segregation in the South.

Joe Azbell, “Blast Rocks Residence of Bus Boycott Leader,” 31 January 1956, in Papers 3:114–115 .

Baker to King, 24 February 1956, in Papers 3:139 .

Burks, “Trailblazers: Women in the Montgomery Bus Boycott,” in Women in the Civil Rights Movement , ed. Crawford et al., 1990.

“Don’t Ride the Bus,” 2 December 1955, in Papers 3:67 .

U. J. Fields, Minutes of Montgomery Improvement Association Founding Meeting, 5 December 1955, in Papers 3:68–70 .

Gregg to King, 2 April 1956, in Papers 3:211–212 .

Indictment, State of Alabama v. M. L. King, Jr., et al. , 21 February 1956, in Papers 3:132–133 .

Introduction, in Papers 3:3–7 ; 17–21 ; 29 .

Jack to King, 16 March 1956, in Papers 3:178–179 .

Judgment and Sentence of the Court, State of Alabama v. M. L. King, Jr. , 22 March 1956, in Papers 3:197 .

King, Statement on Ending the Bus Boycott, 20 December 1956, in Papers 3:485–487 .

King, Stride Toward Freedom , 1958.

King, Testimony in State of Alabama v. M. L. King, Jr. , 22 March 1956, in Papers 3:183–196 .

King to the National City Lines, Inc., 8 December 1955, in Papers 3:80–81 .

“A Letter from the Women’s Political Council to the Mayor of Montgomery, Alabama,” in Eyes on the Prize , ed. Carson et al., 1991.

MIA Mass Meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church, 5 December 1955, in Papers 3:71–79 .

Nelson to King, 21 March 1956, in Papers 3:182–183 .

Parks and Haskins, Rosa Parks , 1992.

Robinson, Montgomery Bus Boycott , 1987.

Stanley Rowland, Jr., “2,500 Here Hail Boycott Leader,” New York Times , 26 March 1956.

Rustin to King, 23 December 1956, in Papers 3:491–494 .

- Modern History

Why was the Montgomery Bus Boycott so successful?

On December 1, 1955, a single act of defiance by Rosa Parks against racial segregation on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus ignited a year-long boycott that would become a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott, led by a young Martin Luther King Jr., mobilized the African American community in a collective stand against injustice, challenging the deeply entrenched laws of segregation in the South.

This historic protest signaled the power of nonviolent resistance and grassroots activism in the fight for racial equality.

Here is how it happened.

What were the causes of the boycott?

Before the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the city of Montgomery, Alabama, like much of the American South, enforced strict racial segregation laws, known as Jim Crow laws, which mandated separate public facilities for white and black citizens.

Public transportation was no exception, with buses segregated by race and black passengers often subjected to humiliating treatment.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks , a seamstress and a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery bus, as was required by law.

Her arrest for this act of civil disobedience sparked outrage within the African American community.

In response, black leaders in Montgomery, including a young pastor named Martin Luther King Jr. , organized a meeting at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church to discuss a course of action.

They formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to oversee the boycott and chose King as its president, recognizing his leadership potential and oratorical skills.

How did the Montgomery Bus Boycott work?

The Montgomery Bus Boycott officially began on December 5, 1955, the day of Rosa Parks' trial.

In preparation, flyers were distributed and announcements were made in black churches throughout the city, calling for African Americans to avoid using the buses on that day.

The response was overwhelming, with an estimated 90% of Montgomery's black residents participating in the boycott on the first day.

The boycotters' demands were simple: courteous treatment by bus drivers, first-come-first-served seating with blacks filling seats from the back and whites from the front, and the employment of black bus drivers on predominantly black routes.

The success of the initial boycott led to a meeting at the Holt Street Baptist Church, where more than 5,000 black residents gathered to discuss the possibility of extending the protest.

With Martin Luther King Jr. emerging as a leading voice, the community decided to continue the boycott until their demands for fair treatment on the buses were met.

The boycott, initially planned to last for just one day, stretched on for 381 days, severely impacting the city's transit system and drawing international attention.

How did the authorities respond?

The city's response was initially dismissive, and the boycotters' resolve was met with resistance from white officials and citizens.

The city government and the bus company refused to negotiate, and legal and economic pressure was applied to try to break the boycott.

Despite these challenges, the black community's commitment to the boycott remained strong.

They organized carpool systems, and many walked long distances to work, school, and church.

The city's legal system targeted the boycott with injunctions and lawsuits, aiming to cripple the movement by arresting its leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., on charges related to the boycott.

Economic pressure was also applied, as many black workers, who were participating in the boycott, faced threats of job loss or actual termination.

King's eloquence and conviction were evident in his speeches and sermons, which he used to articulate the goals of the boycott and to call for unity and perseverance.

His home and the churches where he spoke became targets for segregationist violence, with his house being bombed in January 1956.

Why did the boycott end?

The successful conclusion of the boycott, with the Supreme Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional, was a testament to the effectiveness of coordinated, nonviolent protest.

This Supreme Court ruling not only desegregated buses in Montgomery but also set a legal precedent that would be used to challenge other forms of segregation.

The boycott also propelled Martin Luther King Jr. into the national spotlight, establishing him as a prominent leader of the Civil Rights Movement.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott had a profound impact on the Civil Rights Movement, setting a precedent for nonviolent protest and serving as a catalyst for future civil rights actions.

The successful boycott demonstrated the power of collective action and the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance, inspiring similar protests and boycotts across the South.

It also brought national and international attention to the struggle for civil rights in the United States, highlighting the injustices of segregation and racial discrimination.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott is often seen as the beginning of a new phase in the Civil Rights Movement, one that focused on direct action and mass mobilization.

It laid the groundwork for future campaigns, such as the sit-ins , Freedom Rides , and the March on Washington, which further advanced the cause of civil rights and social justice in America.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Written by: Stewart Burns, Union Institute & University

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how and why various groups responded to calls for the expansion of civil rights from 1960 to 1980

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with the Jackie Robinson Narrative, The Little Rock Nine Narrative, The Murder of Emmett Till Narrative, and the Rosa Parks’s Account of the Montgomery Bus Boycott (Radio Interview), April 1956 Primary Source to discuss the rise of the African American civil rights movement pre-1960.

Rosa Parks launched the Montgomery bus boycott when she refused to give up her bus seat to a white man. The boycott proved to be one of the pivotal moments of the emerging civil rights movement. For 13 months, starting in December 1955, the black citizens of Montgomery protested nonviolently with the goal of desegregating the city’s public buses. By November 1956, the Supreme Court had banned the segregated transportation legalized in 1896 by the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. Montgomery’s boycott was not entirely spontaneous, and Rosa Parks and other activists had prepared to challenge segregation long in advance.

On December 1, 1955, a tired Rosa L. Parks left the department store where she worked as a tailor’s assistant and boarded a crowded city bus for the ride home. She sat down between the “whites only” section in the front and the “colored” section in the back. Black riders were to sit in this middle area only if the back was filled. When a white man boarded, the bus driver ordered four African American passengers to stand so the white passenger could sit. The other riders reluctantly got up, but Parks refused. She knew she was not violating the segregation law, because there were no vacant seats. The police nevertheless arrived and took her to jail.

Parks had not planned her protest, but she was a civil rights activist well trained in civil disobedience so she remained calm and resolute. Other African American women had challenged the community’s segregation statutes in the past several months, but her cup of forbearance had run over. “I had almost a life history of being rebellious against being mistreated because of my color,” Parks recalled. On this occasion more than others “I felt that I was not being treated right and that I had a right to retain the seat that I had taken.” She was fighting for her natural and constitutional rights when she protested against the treatment that stripped away her dignity. “When I had been pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed. I had decided that I would have to know once and for all what rights I had as a human being and a citizen.” She was attempting to “bring about freedom from this kind of thing.”

Perhaps the incident was not as spontaneous as it appeared, however. Parks was an active participant in the civil rights movement for several years and had served as secretary of both the Montgomery and Alabama state NAACP. She founded the youth council of the local NAACP and trained the young people in civil rights activism. She had even discussed challenging the segregated bus system with the youth council before 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat the previous March. Ill treatment on segregated city buses had festered into the most acute problem in the black community in Montgomery. Segregated buses were part of a system that inflicted Jim Crow segregation upon African Americans.

In 1949, a group of professional black women and men had formed the Women’s Political Council (WPC) of Montgomery. They were dedicated to organizing African Americans to demand equality and civil rights by seeking to change Jim Crow segregation in public transportation. In May 1954, WPC president Jo Ann Robinson informed the mayor that African Americans in the city were considering launching a boycott.

The WPC converted abuse on buses into a glaring public issue, and the group collaborated with the NAACP and other civil rights organizations to challenge segregation there. Parks was bailed out of jail by local NAACP leader, E. D. Nixon, who was accompanied by two liberal whites, attorney Clifford Durr and his wife Virginia Foster Durr, leader of the anti-segregation Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF). Virginia Durr had become close friends with Parks. In fact, she helped fund Parks’s attendance at a workshop for two weeks on desegregating schools only a few months before.

The Durrs and Nixon had worked with Parks to plot a strategy for challenging the constitutionality of segregation on Montgomery buses. After Parks’s arrest, Robinson agreed with them and thought the time was ripe for the planned boycott. She worked with two of her students, staying up all night mimeographing flyers announcing a one-day bus boycott for Monday, December 5.

Because of ministers’ leadership in the vibrant African American churches in the city, Nixon called on the ministers to win their support for the boycott. Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., a young and relatively unknown minister of the middle-class Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, was unsure about the timing but offered assistance. Baptist minister Ralph Abernathy eagerly supported the boycott.

On December 5, African Americans boycotted the buses. They walked to work, carpooled, and took taxis as a measure of solidarity. Parks was convicted of violating the segregation law and charged a $14 fine. Because of the success of the boycott, black leaders formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to continue the protest and surprisingly elected Reverend King president.

Rosa Parks, with Martin Luther King Jr. in the background, is pictured here soon after the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

After earning his PhD at Boston University’s School of Theology, King had returned to the Deep South with his new bride, Coretta Scott, a college-educated, rural Alabama native. On the night of December 5, 1955, the 26-year-old pastor presided over the first MIA mass meeting, in a supercharged atmosphere of black spirituality. Participants felt the Holy Spirit was alive that night with a palpable power that transfixed. When King rose to speak, unscripted words burst out of him, a Lincoln-like synthesis of the rational and emotional, the secular and sacred. The congregants must protest, he said, because both their divinity and their democracy required it. They would be honored by future generations for their moral courage.

The participants wanted to continue the protest until their demands for fairer treatment were met as well as establishment of a first-come, first-served seating system that kept reserved sections. White leaders predicted that the boycott would soon come to an end because blacks would lose enthusiasm and accept the status quo. When blacks persisted, some of the whites in the community formed the White Citizens’ Council, an opposition movement committed to preserving white supremacy.

The bus boycott continued and was supported by almost all of Montgomery’s 42,000 black residents. The women of the MIA created a complex carpool system that got black citizens to work and school. By late December, city commissioners were concerned about the effects of the boycott on business and initiated talks to try to resolve the dispute. The bus company (which now supported integrated seating) feared it might go bankrupt and urged compromise. However, the commissioners refused to grant any concessions and the negotiations broke down over the next few weeks. The commissioners adopted a “get tough” policy when it became clear that the boycott would continue. Police harassed carpool drivers. They arrested and jailed King on a petty speeding charge when he was helping out one day. Angry whites tried to terrorize him and bombed his house with his wife and infant daughter inside, but no one was injured. Drawing from the Sermon on the Mount, the pastor persuaded an angry crowd to put their guns away and go home, preventing a bloody riot. Nixon’s home and Abernathy’s church were also bombed.

On January 30, MIA leaders challenged the constitutionality of bus segregation because the city refused their moderate demands. Civil rights attorney Fred Gray knew that a state case would be unproductive and filed a federal lawsuit. Meanwhile, city leaders went on the offensive and indicted nearly 100 boycott leaders, including King, on conspiracy charges. King’s trial and conviction in March 1956 elicited negative national publicity for the city on television and in newspapers. Sympathetic observers sent funds to Montgomery to support the movement.

In June 1956, the Montgomery federal court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that Alabama’s bus segregation laws violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equality and were unconstitutional. The Supreme Court upheld the decision in November. In the wake of the court victories, MIA members voted to end the boycott. Black citizens triumphantly rode desegregated Montgomery’s buses on December 21, 1956.

A diagram of the Montgomery bus where Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat was used in court to ultimately strike down segregation on the city’s buses.

The Montgomery bus boycott made King a national civil rights leader and charismatic symbol of black equality. Other black ministers and activists like Abernathy, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Bayard Rustin, and Ella Baker also became prominent figures in the civil rights movement. The ministers formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to protest white supremacy and work for voting rights throughout the South, testifying to the importance of black churches and ministers as a vital element of the civil rights movement.

The Montgomery bus boycott paved the way for the civil rights movement to demand freedom and equality for African Americans and transformed American politics, culture, and society by helping create the strategies, support networks, leadership, vision, and spiritual direction of the movement. It demonstrated that ordinary African American citizens could band together at the local level to demand and win in their struggle for equal rights and dignity. The Montgomery experience laid the foundations for the next decade of a nonviolent direct-action movement for equal civil rights for African Americans.

Review Questions

1. All of the following are true of Rosa Parks except

- she served as secretary of the Montgomery NAACP

- she trained young people in civil rights activism

- she unintentionally challenged the bus segregation laws of Montgomery

- she was well-trained in civil disobedience

2. The initial demand of those who boycotted the Montgomery Bus System was for the city to

- hire more black bus drivers in Montgomery

- arrest abusive bus drivers

- remove the city commissioners

- modify Jim Crow laws in public transportation

3. The Montgomery Improvement Association was formed in 1955 primarily to

- bring a quick end to the bus boycott

- maintain segregationist policies on public buses

- provide carpool assistance to the boycotters

- organize the bus protest

4. As a result of the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott, Martin Luther King Jr. was

- elected mayor of Montgomery

- targeted as a terrorist and held in jail for the duration of the boycott

- recognized as a new national voice for African American civil rights

- made head pastor of his church

5. The Federal court case Browder v. Gayle established that

- the principles in Brown v. Board of Education were also relevant in the Montgomery Bus Boycott

- the Montgomery bus segregation laws were a violation of the constitutional guarantee of equality

- the principles of Plessy v. Ferguson were similar to those in the Montgomery bus company

- the conviction of Martin Luther King Jr. was unconstitutional

6. All the following resulted from the Montgomery bus boycott except

- the formation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

- the emergence of Martin Luther King Jr. as a national leader

- the immediate end of Jim Crow laws in Alabama

- negative national publicity for the city of Montgomery

Free Response Questions

- Explain how the Montgomery Bus Boycott affected the civil rights movement.

- Describe how the Montgomery Bus Boycott propelled Martin Luther King Jr. to national notice.

AP Practice Questions

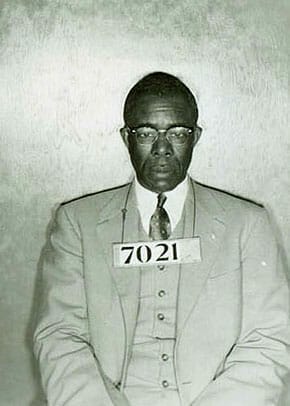

Rosa Parks being fingerprinted by Deputy Sheriff D. H. Lackey after her arrest in December 1955.

1. Which of the following had the most immediate impact on events in the photograph?

- The integration of the U.S. military

- The Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson

- The Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education

- The integration of Little Rock (AR) Central High School

2. The actions leading to the provided photograph were similar to those associated with

- the labor movement in the 1920s

- the women’s suffrage movement in the early twentieth century

- the work of abolitionists in the 1850s

- the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s

3. The situation depicted in the provided photograph contributed most directly to the

- economic development of the South

- growth of the suburbs

- growth of the civil right movement

- evolution of the anti-war movement

Primary Sources

Burns, Steward, ed. Daybreak of Freedom: The Montgomery Bus Boycott. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Garrow, David J, ed. Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson . Nashville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

Greenlee, Marcia M. “Interview with Rosa McCauley Parks.” August 22-23, 1978, Detroit. Cambridge, MA: Black Women Oral History Project, Harvard University. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:45175350$14i

Suggested Resources

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 . New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

Brinkley, Douglas. Rosa Parks . New York: Penguin, 2000.

Rosa Parks Museum, Montgomery, AL. www.troy.edu/rosaparks

Williams, Juan. Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965 . New York: Penguin, 2013.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 20, 2024 | Original: November 9, 2009

Rosa Parks (1913—2005) helped initiate the civil rights movement in the United States when she refused to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery, Alabama bus in 1955. Her actions inspired the leaders of the local Black community to organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott . Led by a young Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. , the boycott lasted more than a year—during which Parks not coincidentally lost her job—and ended only when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional. Over the next half-century, Parks became a nationally recognized symbol of dignity and strength in the struggle to end entrenched racial segregation .

Rosa Parks’ Early Life

Rosa Louise McCauley was born in Tuskegee, Alabama , on February 4, 1913. She moved with her parents, James and Leona McCauley, to Pine Level, Alabama, at age 2 to reside with Leona’s parents. Her brother, Sylvester, was born in 1915, and shortly after that her parents separated.

Did you know? When Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat in 1955, it wasn’t the first time she’d clashed with driver James Blake. Parks stepped onto his very crowded bus on a chilly day 12 years earlier, paid her fare at the front, then resisted the rule in place for Black people to disembark and re-enter through the back door. She stood her ground until Blake pulled her coat sleeve, enraged, to demand her cooperation. Parks left the bus rather than give in.

Rosa’s mother was a teacher, and the family valued education. Rosa moved to Montgomery, Alabama, at age 11 and eventually attended high school there, a laboratory school at the Alabama State Teachers’ College for Negroes. She left at 16, early in 11th grade, because she needed to care for her dying grandmother and, shortly thereafter, her chronically ill mother. In 1932, at 19, she married Raymond Parks, a self-educated man 10 years her senior who worked as a barber and was a long-time member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ). He supported Rosa in her efforts to earn her high-school diploma, which she ultimately did the following year.

Rosa Parks: Roots of Activism

Raymond and Rosa, who worked as a seamstress, became respected members of Montgomery’s large African American community. Co-existing with white people in a city governed by “ Jim Crow ” (segregation) laws, however, was fraught with daily frustrations: Black people could attend only certain (inferior) schools, could drink only from specified water fountains and could borrow books only from the “Black” library, among other restrictions.

Although Raymond had previously discouraged her out of fear for her safety, in December 1943, Rosa also joined the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP and became chapter secretary . She worked closely with chapter president Edgar Daniel (E.D.) Nixon. Nixon was a railroad porter known in the city as an advocate for Black people who wanted to register to vote, and also as president of the local branch of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union .

December 1, 1955: Rosa Parks Is Arrested

On Thursday, December 1, 1955, the 42-year-old Rosa Parks was commuting home from a long day of work at the Montgomery Fair department store by bus. Black residents of Montgomery often avoided municipal buses if possible because they found the Negroes-in-back policy so demeaning. Nonetheless, 70 percent or more riders on a typical day were Black, and on this day Rosa Parks was one of them.

Segregation was written into law; the front of a Montgomery bus was reserved for white citizens, and the seats behind them for Black citizens. However, it was only by custom that bus drivers had the authority to ask a Black person to give up a seat for a white rider. There were contradictory Montgomery laws on the books: One said segregation must be enforced, but another, largely ignored, said no person (white or Black) could be asked to give up a seat even if there were no other seat on the bus available.

Nonetheless, at one point on the route, a white man had no seat because all the seats in the designated “white” section were taken. So the driver told the riders in the four seats of the first row of the “colored” section to stand, in effect adding another row to the “white” section. The three others obeyed. Parks did not.

“People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired,” wrote Parks in her autobiography, “but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically… No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Eventually, two police officers approached the stopped bus, assessed the situation and placed Parks in custody.

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Although Parks used her one phone call to contact her husband, word of her arrest had spread quickly and E.D. Nixon was there when Parks was released on bail later that evening. Nixon had hoped for years to find a courageous Black person of unquestioned honesty and integrity to become the plaintiff in a case that might become the test of the validity of segregation laws. Sitting in Parks’ home, Nixon convinced Parks—and her husband and mother—that Parks was that plaintiff. Another idea arose as well: The Black population of Montgomery would boycott the buses on the day of Parks’ trial, Monday, December 5. By midnight, 35,000 flyers were being mimeographed to be sent home with Black schoolchildren, informing their parents of the planned boycott.

On December 5, Parks was found guilty of violating segregation laws, given a suspended sentence and fined $10 plus $4 in court costs. Meanwhile, Black participation in the boycott was much larger than even optimists in the community had anticipated. Nixon and some ministers decided to take advantage of the momentum, forming the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to manage the boycott, and they elected Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.–new to Montgomery and just 26 years old—as the MIA’s president.

As appeals and related lawsuits wended their way through the courts, all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court , the Montgomery Bus Boycott engendered anger in much of Montgomery’s white population as well as some violence, and Nixon’s and Dr. King’s homes were bombed . The violence didn’t deter the boycotters or their leaders, however, and the drama in Montgomery continued to gain attention from the national and international press.

On November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional; the boycott ended December 20, a day after the Court’s written order arrived in Montgomery. Parks—who had lost her job and experienced harassment all year—became known as “the mother of the civil rights movement.”

Rosa Parks's Life After the Boycott

Facing continued harassment and threats in the wake of the boycott, Parks, along with her husband and mother, eventually decided to move to Detroit, where Parks’ brother resided. Parks became an administrative aide in the Detroit office of Congressman John Conyers Jr. in 1965, a post she held until her 1988 retirement. Her husband, brother and mother all died of cancer between 1977 and 1979. In 1987, she co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development, to serve Detroit’s youth.

In the years following her retirement, she traveled to lend her support to civil-rights events and causes and wrote an autobiography, Rosa Parks: My Story . In 1999, Parks was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor the United States bestows on a civilian. (Other recipients have included George Washington , Thomas Edison , Betty Ford and Mother Teresa.) When she died at age 92 on October 24, 2005, she became the first woman in the nation’s history to lie in honor at the U.S. Capitol.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Agriculture

- Arts & Literature

- Business & Industry

- Geography & Environment

- Government & Politics

- Science & Technology

- Sports & Recreation

- Organizations

- Collections

- Quick Facts

Montgomery Bus Boycott

In March 1955, Claudette Colvin , a 15-year-old high school junior, refused to give up her bus seat to a white person. She was arrested for violating the segregated seating ordinances and mistreated by police. This angered the black community and sparked a brief, informal boycott of buses by many black residents. In August, Montgomery’s black community was shaken by the brutal lynching of 14-year-old Chicago native Emmett Till in Mississippi. Two months later, 18-year-old Mary Louise Smith, a house maid, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat. African Americans in Montgomery felt beleaguered.

Although Parks did not plan her calm, determined protest, she recalled that she had a life history of rebelling against racial mistreatment. She believed that she had been “pushed as far as [she] could stand to be pushed.” Parks was arrested and then bailed out that night by friend E. D. Nixon , a Pullman car porter who had headed the local and Alabama state branches of the NAACP, and by two white friends, attorney Clifford Durr and his activist wife, Virginia Durr . The Durrs and Nixon persuaded Parks to allow her arrest to be used as a test case for the constitutionality of bus segregation.

At the outset white officials and opinion leaders believed that the bus boycott would collapse quickly and that blacks were not capable of a long-term protest campaign. The white community solidified in opposition, spurred by growth of the local White Citizens’ Council , but a few brave white citizens, such as Virginia and Clifford Durr and city librarian Juliette Hampton Morgan , supported the civil rights effort.

In June 1956, halfway through the boycott, the federal court in Montgomery ruled in Browder v. Gayle that Alabama’s bus segregation laws, both city and state, violated the Fourteenth Amendment and were thus unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld that decision in November, and MIA members voted to end the boycott. At the same moment, the city’s belated injunction shut down the carpool system by making it illegal, but those who had driven joined those who had been walking all along. After the city government lost its final appeal in the Supreme Court, black citizens desegregated Montgomery’s buses on December 21, 1956. White extremists fired on buses and bombed churches, but the year-long bus protest ended in victory over the city’s Jim Crow laws.

Additional Resources

Boycott. DVD, directed by Clark Johnson. Los Angeles: Home Box Office, Inc., 2001.

Burns, Stewart, ed. Daybreak of Freedom: The Montgomery Bus Boycott . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Eyes on the Prize: Awakenings (1954-1956). DVD, directed by Henry Hampton. Boston: Blackside, 1987.

Gray, Fred D. Bus Ride to Justice . Montgomery: Black Belt Press, 1994.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. Stride Toward Freedom . New York: Harper, 1958.

Robinson, Jo Ann Gibson. The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It . Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

Thornton, J. Mills III. Dividing Lines . Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

External Links

- Civil Rights Digital Library

- Troy University Rosa Parks Museum

- Justice Without Violence – Alabama Public Television

Stewart Burns Williams College

Last Updated

- Share on Facebook

- Send via Email

Related Articles

Greenbackism in Alabama

The Greenback movement, also referred to as Greenbackism, was a short-lived coalition of farmers and laborers that arose in the mid-1870s to protest a variety of federal monetary policies. The movement made allies with organized labor and died out in the early 1880s but managed to influence the Populist movement…

Jay Carrington Scott

Jay Carrington Scott (1953-2009) was a notable saxophone player who learned his trade in the music clubs of Dothan, Houston County, and the Wiregrass region. He later traveled the country, playing often in Las Vegas, and recorded with many notable groups and artists of the late 1970s and early 1980s.…

Alabama Public Television

Established in 1953, Alabama Public Television (APT) was the first educational television network in the United States and has served Alabama for more than five decades. Headquartered in Birmingham, the organization pioneered the use of microwave towers to transmit its signals and was the first television station in the state…

Alabama Nature Center

The Alabama Nature Center (ANC) is an outdoor environmental education facility located in Millbrook, in southwestern Elmore County. Administered by the Alabama Wildlife Federation (AWF), it offers educational programs and activities to students, educators, church and civic groups, and the general public. ANC is located on the 350-acre former estate…

Share this Article

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

The montgomery bus boycott.

Years before the boycott, Dexter Avenue minister Vernon Johns sat down in the "whites-only" section of a city bus. When the driver ordered him off the bus, Johns urged other passengers to join him. On March 2, 1955, a black teenager named Claudette Colvin dared to defy bus segregation laws and was forcibly removed from another Montgomery bus.

Nine months later, Rosa Parks - a 42-year-old seamstress and NAACP member- wanted a guaranteed seat on the bus for her ride home after working as a seamstress in a Montgomery department store. After work, she saw a crowded bus stop. Knowing that she would not be able to sit, Parks went to a local drugstore to buy an electric heating pad. After shopping, Parks entered the less crowded Cleveland Avenue bus and was able to find an open seat in the 'colored' section of the bus for her ride home.

Despite having segregated seating arrangements on public buses, it was routine in Montgomery for bus drivers to force African Americans out of their seats for a white passenger. There was very little African Americans could do to stop the practice because bus drivers in Montgomery had the legal ability to arrest passengers for refusing to obey their orders. After a few stops on Parks’ ride home, the white seating section of the bus became full. The driver demanded that Parks give up her seat on the bus so a white passenger could sit down. Parks refused to surrender her seat and was arrested for violating the bus driver’s orders.

Organizing the Boycott

Montgomery's black citizens reacted decisively to the incident. By December 2, schoolteacher Jo Ann Robinson had mimeographed and delivered 50,000 protest leaflets around town. E.D. Nixon, a local labor leader, organized a December 4 meeting at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church , where local black leaders formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA)to spearhead a boycott and negotiate with the bus company.

Over 70% of the cities bus patrons were African American and the one-day boycott was 90% effective. The MIA elected as their president a new but charismatic preacher, Martin Luther King Jr. Under his leadership, the boycott continued with astonishing success. The MIA established a carpool for African Americans. Over 200 people volunteered their car for a car pool and roughly 100 pickup stations operated within the city. To help fund the car pool, the MIA held mass gatherings at various African American churches where donations were collected and members heard news about the success of the boycott.

Roots in Brown v Board

Fred Gray, member and lawyer of the MIA, organized a legal challenge to the city ordinances requiring segregation on Montgomery buses. Before 1954, the Plessy v. Ferguson decision ruled that segregation was constitutional as long as it was equal. Yet, the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawed segregation in public schools. Therefore, it opened the door to challenge segregation in other areas as well, such as city busing. Gray gathered Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, Claudette Colvin and Mary Louise Smith to challenge the constitutionality of the city busing laws. All four of the women had been previously mistreated on the city buses because of their race. The case took the name Browder v. Gayle. Gray argued their 14th Amendment right to equal protection of the law was violated, the same argument made in the Brown v. Board of Education case.

On June 5, 1956, a three-judge U.S. District Court ruled 2-1 that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional. The majority cited Brown v. Board of Education as a legal precedent for desegregation and concluded, “In fact, we think that Plessy v. Ferguson has been impliedly, though not explicitly, overruled,…there is now no rational basis upon which the separate but equal doctrine can be validly applied to public carrier transportation...”

The city of Montgomery appealed the U.S. District Court decision to the U.S. Supreme Court and continued to practice segregation on city busing.

For nearly a year, buses were virtually empty in Montgomery. Boycott supporters walked to work--as many as eight miles a day--or they used a sophisticated system of carpools with volunteer drivers and dispatchers. Some took station-wagon "rolling taxis" donated by local churches.

Montgomery City Lines lost between 30,000 and 40,000 bus fares each day during the boycott. The bus company that operated the city busing had suffered financially from the seven month long boycott and the city became desperate to end the boycott. Local police began to harass King and other MIA leaders. Car pool drivers were arrested and taken to court for petty traffic violations. Despite all the harassment, the boycott remained over 90% successful. African Americans took pride in the inconveniences caused by limited transportation. One elderly African American woman replied that, “My soul has been tired for a long time. Now my feet are tired, and my soul is resting.” The promise of equality declared in Brown v. Board of Education for Montgomery African Americans helped motivate them to continue the boycott.

The company reluctantly desegregated its buses only after November 13, 1956, when the Supreme Court ruled Alabama's bus segregation laws unconstitutional.

Beginning a Movement

The Montgomery bus boycott began the modern Civil Rights Movement and established Martin Luther King Jr. as its leader. King instituted the practice of massive non-violent civil disobedience to injustice, which he learned from studying Gandhi. Montgomery, Alabama became the model of massive non-violent civil disobedience that was practiced in such places as Birmingham, Selma, and Memphis. Even though the Civil Rights Movement was a social and political movement, it was influenced by the legal foundation established from Brown v. Board of Education.

Brown overturned the long held practice of the “separate but equal” doctrine established by Plessy. From then on, any legal challenge on segregation cited Brown as a precedent for desegregation. Without Brown, it is impossible to know what would have happened in Montgomery during the boycott.

The boycott would have been difficult to continue because the city would have won its challenge to shut down the car pool. Without the car pool and without any legal precedent to end segregation, the legal process could have lasted years. Those involved in the boycott might have lost hope and given up with the lack of progress. However, the precedent established by Brown gave boycotters hope that a legal challenge would successfully end segregation on city buses. Therefore, the influence of Brown on the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Civil Rights Movement is undeniable. King described Brown’s influence as, “To all men of good will, this decision came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of human captivity. It came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of colored people throughout the world who had had a dim vision of the promised land of freedom and justice . . . this decision came as a legal and sociological deathblow to an evil that had occupied the throne of American life for several decades.”

You Might Also Like

- selma to montgomery national historic trail

- montgomery bus boycott

- civil rights

Selma To Montgomery National Historic Trail

Last updated: September 21, 2022

A blog of the U.S. National Archives

Pieces of History

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

In commemoration of the anniversary of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, today’s post comes from Sarah Basilion, an intern in the National Archives History Office.

Sixty years ago, Rosa Parks, a 42-year-old black woman, refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery, Alabama, public bus.

On December 1, 1955, Parks, a seamstress and secretary for the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was taking the bus home after a long day of work.

The white section of the bus had filled, so the driver asked Parks to give up her seat in the designated black section of the bus to accommodate a white passenger.

She refused to move.

When it became apparent after several minutes of argument that Parks would not relent, the bus driver called the police. Parks was arrested for being in violation of Chapter 6, Section 11, of the Montgomery City Code, which upheld a policy of racial segregation on public buses.

Parks was not the first person to engage in this act of civil disobedience.

Earlier that year, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus. She was arrested, but local civil rights leaders were concerned that she was too young and poor to be a sympathetic plaintiff to challenge segregation.

Parks—a middle-class, well-respected civil rights activist—was the ideal candidate.

Just a few days after Parks’s arrest, activists announced plans for the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

The boycott, which officially began December 5, 1955, did not support just Parks but countless other African Americans who had been arrested for the same reason.

E. D. Nixon, president of the local NAACP chapter, called for all African-American citizens to boycott the public bus system to protest the segregation policy. Nixon and his supporters vowed to abstain from riding Montgomery public buses until the policy was abolished.

Instead of buses, African Americans took taxis driven by black drivers who had lowered their fares in support of the boycott, walked, cycled, drove private cars, and even rode mules or drove in horse-drawn carriages to get around. African-American citizens made up a full three-quarters of regular bus riders, causing the boycott to have a strong economic impact on the public transportation system and on the city of Montgomery as a whole.

The boycott was proving to be a successful means of protest.

The city of Montgomery tried multiple tactics to subvert the efforts of boycotters. They instituted regulations for cab fares that prevented black cab drivers from offering lower fares to support boycotters. The city also pressured car insurance companies to revoke or refuse insurance to black car owners so they could not use their private vehicles for transportation in lieu of taking the bus.

Montgomery’s efforts were futile as the local black community, with the support of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., churches—and citizens around the nation—were determined to continue with the boycott until their demand for racially integrated buses was met.

The boycott lasted from December 1, 1955, when Rosa Parks was arrested, to December 20, 1956, when Browder v. Gayle , a Federal ruling declaring racially segregated seating on buses to be unconstitutional, took effect.

Although it took more than a year, Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat on a public bus sparked incredible change that would forever impact civil rights in the United States.

Parks continued to raise awareness for the black struggle in America and the Civil Rights movement for the rest of her life. For her efforts she was awarded both the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor given by the executive branch, and the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor given by the legislative branch.

To learn more about the life of Rosa Parks, read Michael Hussey’s 2013 Pieces of History post Honoring the “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement. ”

And plan your visit to the National Archives to view similar documents in our “ Records of Rights ” exhibit or explore documents in our online catalog .

Copies of documents relating to Parks’s arrest submitted as evidence in the Browder v. Gayle case are held in the National Archives at Atlanta in Morrow, Georgia.

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

Claudette Colvin at age 13, April 20, 1953.

In 1955, Claudette Colvin, a high school student in Montgomery, Alabama boarded the city bus. Her ride went without incident, until she was asked to move to the back of the bus and give her seat to a white passenger. She refused replying to the bus driver that it was her “constitutional right” to stay seated. For her refusal, Colvin was removed from the bus and arrested.

A few months later, Rosa Parks, another Montgomery resident and a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was traveling home on the bus. When Parks was asked to move to the back, she refused, and like Colvin she was arrested.

Colvin and Parks along with other early protestors sparked a yearlong boycott of the Montgomery bus system. The boycott culminated in the desegregation of public transportation in Alabama and throughout the country. Although the movement is best known for catapulting the career of a young reverend, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the boycott was largely planned and executed by African American women. The Women’s Political Council (WPC) was an organization of black women active in anti-segregation activities and politics. It was largely responsible for publicizing the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Jo Ann Robinson was the president of WPC and a teacher at Alabama State College when the boycott started. She recognized the inequality for African Americans on public transportation, but was unable to gain support for a large-scale boycott. With the arrest of Parks, Robinson seized the opportunity to protest the bus system's systematic discrimination and pushed the WPC to get to work.

One of WPC’s many jobs was to publicize the boycott. This was done by printing leaflets and passing them out around the city. Robinson also reached out to other organizations like the NAACP and the Montgomery Improvement Association. Women not only represented leadership in the movement, but they also handled the day to day planning for protesters. They set up a car pool for women who worked long distances from their homes. Despite constant threats of violence, the boycott lasted for almost a year. On December 20, 1956, the Supreme Court upheld a lower court decision that stated it was unconstitutional to discriminate on public transit. With the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Civil Rights activists turned their attention to the integration of public schools.

By Arlisha Norwood, NWHM Fellow

You Might Also Like

Mary church terrell , belva lockwood and the precedents she set for women’s rights, women’s rights lab: black women’s clubs, educational equality & title ix:.

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Social Movements — Montgomery Bus Boycott

Essays on Montgomery Bus Boycott

The Montgomery Bus Boycott is a significant event in history that sparked the civil rights movement in the United States. Writing an essay about the Montgomery Bus Boycott can help you learn about the courage and determination of the people involved and the impact it had on society.

When choosing a topic for your essay about the Montgomery Bus Boycott, consider focusing on specific aspects such as the key figures involved, the impact on civil rights, the role of community activism, or the lasting effects on public transportation. You can also explore the social, political, and economic factors that led to the boycott and its significance in the larger context of the civil rights movement.

For an argumentative essay about the Montgomery Bus Boycott, you can explore topics such as the role of nonviolent resistance, the effectiveness of boycotts as a means of protest, or the relationship between segregation and public transportation. For a cause and effect essay, you could examine the catalysts that led to the boycott and its aftermath, or the long-term consequences on racial segregation and equality. In an opinion essay, you can express your personal views on the impact of the boycott and its relevance in today's society. And for an informative essay, you can delve into the historical background, key events, and the broader implications of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

For a thesis statement on the Montgomery Bus Boycott, you can focus on topics such as the defiance against segregation, the power of grassroots movements, or the role of civil disobedience in creating social change. In the of your essay, you can provide context about the events leading up to the boycott, the key players involved, and the significance of the boycott in challenging racial segregation. In the , you can summarize the key points of your essay and reflect on the lasting impact of the Montgomery Bus Boycott on civil rights and social justice.

Writing an essay about the Montgomery Bus Boycott allows you to explore a pivotal moment in history and its relevance to contemporary issues. Whether you choose to argue a point, explore causes and effects, express your opinion, or provide information, there are many engaging topics to consider when writing about the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

How The Montgomery Bus Boycott Impacted The Civil Rights of The African-american

Analyzing the efficacy of the bus boycott in montgomery, united states, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Segregation of Bus Passengers and Rosa Parks

The montgomery bus boycott – the start of the fight for freedom, the effectiveness of boycotting as a way to affect societal issues, causes and effects of the montgomery bus boycott, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Role of Black Churches and Community During The Montgomery Bus Boycott

A study of the background of the montgomery bus boycott by bernard law as a way of resisting apartheid and racial bias in the united states, rosa parks and her role in the civil rights movement, an individual's power to change the society: american activists, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Rosa Parks: Mother of The Modern-day Civil Rights Movement

Rosa parks and black history month, relevant topics.

- Civil Disobedience

- Emmett Till

- Me Too Movement

- Gun Violence

- Black Lives Matter

- Illegal Immigration

- Animal Testing

- Gender Equality

- Animal Rights

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Home Lessons IBDP History IB History Paper 1 Topics Prescribed subject 4: Rights and protest Civil Rights Movement in the United States (1954–1965) Montgomery Bus Boycott

Montgomery Bus Boycott

The “Montgomery Bus Boycott”, is a vibrant history lesson plan that brings the past to life in an accessible, engaging, and informative way. This worksheet invites your students to step back into the era of segregation and Jim Crow laws, helping them understand the significant events that led to one of American history’s most memorable acts of peaceful resistance.

The worksheet starts by setting the scene. Students will explore the era of segregation and how it affected everyday life. They’ll understand why Rosa Parks’ simple but powerful act of defiance on a Montgomery city bus became a spark that ignited a nationwide movement for civil rights.

They’ll learn about the extraordinary people behind the scenes, like E.D. Nixon, Ralph David Abernathy, and a young pastor, Martin Luther King Jr., whose leadership turned a local protest into a landmark event in American history. Students can use primary sources to explore these stories and deepen their understanding.

A key part of the lesson is understanding the strategies that made the boycott successful. Students will explore how careful planning, coordination, and community spirit helped keep the boycott going for over a year, despite the many challenges.

This lesson doesn’t shy away from the darker side of history either. Students will delve into the intimidation tactics used by segregation supporters and the courage of those who stood up to them. By looking at primary sources, students can understand the bravery and determination that characterised this period.

The “Montgomery Bus Boycott” worksheet is the perfect resource for teachers who want to give their students a memorable, in-depth, and meaningful exploration of a defining moment in American history. This engaging and student-friendly lesson plan brings history to life in your classroom, igniting a love of learning that will last a lifetime.

Other Lessons you may like:

You need to have an account in order to download

Resource Information

Other related lessons.

Reading Ancient Remains Worksheet

Dive into the ancient world with the “Reading Ancient Remains Worksheet,” a lesson plan designed to bridge the gap between […]

Chinese Civil War Causes and Effects Activity

“IB History: Chinese Civil War Causes and Effects Activity” delves into the dynamic and pivotal conflict that reshaped the 20th […]

Non-violent Resistance to Apartheid

Delve into the heart of South Africa’s turbulent past with “Exploring Non-violent Resistance to Apartheid,” a meticulously crafted lesson plan […]

Travelers Toolkit Infographic

Dive into history with the “Travelers Toolkit Learning to Solve the Past Infographic,” a brilliantly designed tool crafted to enrich […]

What are you teaching?

Don't babylon with last-minute lesson plans, explore our catalogue today., request a lesson, thank you for contacting the cunning history teacher. we will contact you shortly, thank you for your lesson request, login to your account.

Email address

Create an account and download your first 3 lessons free

Forgot pass, enter email or username:, signup for your account, create an account and download your first 3 lessons free.

SIGNUP FOR AN ACCOUNT

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery bus boycott for Leaving Cert History #625Lab

What was the contribution of martin luther king to the montgomery bus boycott and to other aspects of us life.

#625Lab – History , marked 85/100, detailed feedback at the very bottom. You may also like: Leaving Cert History Guide (€).

Martin Luther King, Jr. was a well-known civil rights leader and activist who had a great deal of influence on American society in the 1950s and 1960s. He contributed greatly to the events of the Montgomery bus boycott and to other aspects of US life through his non-violent actions. In 1954 in America, the US Supreme Court removed the legal basis for segregation in education. However, in the southern states Jim Crow laws continued to enforce segregation and discrimination in housing, transport and various public facilities.

In Montgomery, Alabama, a southern city with a long history of racial tension, segregated seating was present on buses. African American people could only sit at the back for the bus and had to stand up for a white people if the front seats were occupied. On the evening of 1 December 1955, an African American seamstress Rosa Parks got on a bus in downtown Montgomery. When asked to move to let a white person sit down, she refused. The police were called and minutes later, Rosa Parks was arrested. Parks was well known and respected in the African American community in Montgomery, and she has been secretary of the Montgomery NAACP. From jail she phoned Daniel Nixon, leader of the NAACP in Alabama. He agreed to pay her bail and decided that they could go the Supreme Court with this case, and boycott the bus. Nixon knew that challenging racism in the supreme courts would require the support of other African American leaders. He contacted the reverend Ralph Abernathy and the reverend Martin Luther King, a popular young baptist minister. King’s popularity in the community gave this case credibility.

A one day bus boycott for December 5, 1955 was organised by the women’s political committee, the day parks was due in court. Meanwhile, threats of violence against bus drivers were present in the African American community. In order to prevent violence, on 2 December Nixon , Abernathy and King called a meeting in King’s church. Over 40 religious and civic leaders from the African American community agreed to support the boycott. Their message was one of non co-operation. Organisers hoped that 60% of the community would back the boycott but it turned out to be almost 100%. King attended Rosa Parks’ trial that day where she was found guilty, and fined $14. Nixon called for an appeal.

The elders of the boycott met up and set up a permanent organisation for the boycott as they had already decided that it should last more than one day. They called it the Montgomery improvement association. Martin Luther King was unanimously elected leader of the group. That evening he addressed a huge crowd at a meeting held by the MIA. He urged them to follow non-violent Christian principles, to use persuasion, not coercion. The MIA wanted segregation on buses to end, black people to be treated with courtesy by bus drivers and for black drivers to be employed on the buses. King closed the meeting by calling on all those in favour to stand. Everybody stood. This was the grinning of King’s important contribution to the Montgomery bus boycott.

King was a dedicated and popular minister at the Dexter Anne Baptist church in Montgomery and was active in the local branch of the NAACP. He was young, energetic and a brilliant public speaker. King and the other leaders held meetings to plan strategy and set up a transportation committee to raise funds and organise alternative transport for African Americans. After Christmas 1955, when it became clear that the African American community were determined it continue the boycott, some white people began to use measures aimed at forcing them to give up. On 22 January the city announced that the boycott was over and that a settlement had been reached. King shut down these rumours by responding quickly and telling the African Americans to ignore these reports. It was quick thinking like this by King that ensured that the bus boycott was a success. He was also arrested for breaking an old law which prohibited boycotts. His arrest and trial made headlines and international news, bringing more publicity to the movement.

On 13 December, the US Supreme Court declared that segregated seating on public buses was unconstitutional. The Supreme court’s decision was to come into operation on 20 December 1956. On 21 December , in a symbolic gesture, King and a white minister, Glenn Smiley, sat together in what was previously a whites-only section on a bus. King and his associates had successfully made segregation on public transport illegal. He had successfully contributed to both the Montgomery bus boycott and to the Black Civil rights movement in America.

In 1957, King helped to set up the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Its aim was to continue working for change, using non-violent tactics. In 1958 the SCLC began its crusade to double the number of African- American voters in the South by 1960. In 1960, some African-American students began ‘sit-ins’ at segregated lunch counters. King supported them and was arrested in October 1960. This brought publicity to the protest. By the end of the year the peaceful sit-in campaign by over 50,000 young people had succeeded in desegregating public facilities in more than 100 cities in the south.

In April 1963, King organised a protest march in Birmingham, Alabama – a big industrial city known for its racial prejudice. The marchers filled the streets day after day, singing ‘We shall Overcome’. King was arrested, and his ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ was one of the most effective documents of the civil rights movements. On 8 May, six thousand African-American children marched through Birmingham. On the following day the police chief, Eugene O’Connor, ordered is men to use water houses, electric cattle prods and dogs against the protesters. Crucially, these events were broadcast live on national television and shocked audiences, winning widespread white support for King. The president sent officials to negotiate with he city authorities. The violence ended and the protestors were granted most of their demands. Kennedy brought in a civil Rights Bill providing for an end to all discrimination and an extension of voting rights for African Americans. This bill was delayed by congress, but King still contributed greatly to the progression of civil rights for African Americans with this protest march.

One of Martin Luther’s most famous contributions to the Black civil rights movement occurred in August of 1963, when King led a march on Washington, D.C to demonstrate for ‘jobs and freedom’. Over 200,00 protestors joined the march and he made his famous ‘I have a dream speech’ . Kennedy feared that the march would make it difficult to get his civil rights bill passed but it was peaceful and orderly, and helped to get the bill passed a year later. The bill was passed in 1964, and it banned discrimination in all public accommodation, outlawed job discrimination and reduced the power of local voter registration boards to disqualify African Americans from voting. This was yet another victory for King and the movement. Martin Luther King condemned the Vietnam war. King said that the war wastes lives and misuses American resources. The Vietnam war went against hi non-violent agenda. This public condemnation contributed to public outcry concerning the war.

In 1964, small-scale violence erupted in Harlem. In August 1965, five days after the civil rights bill was signed by the President, a huge riot broke out in Watts, an African-American ghetto in Los Angeles. For six days, looting and fighting between African-American youths and police raged. The riot greatly upset King and he moved the SCLC headquarters to Chicago, determined to shift his focus from the south to the northern ghettos and the problems of jobs and housing. During the summers of 1966 and 1967, further rioting took place in the north . In 1967, 83 people were killed in 164 different riots, causing over $100 million in damages to property. The civil rights movement became divided as king appealed for calm and denounced the violence and insisted that militants only represented a minority of African Americans. In April 1968, King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. His death seemed to destroy any hope of resolving the race problem.

Martin Luther King made enormous contributions to both the Montgomery bus boycott and to US life by progressing the Civil rights movement through non-violent means. He started a progression towards equality that ultimately resulted in the legal equality between black and white people in America in today’s society. He is remembered to this day as an iconic figure in the civil rights movement , both in America and internationally.