An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines

Jessie s. barrot.

College of Education, Arts and Sciences, National University, Manila, Philippines

Ian I. Llenares

Leo s. del rosario, associated data.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Recently, the education system has faced an unprecedented health crisis that has shaken up its foundation. Given today’s uncertainties, it is vital to gain a nuanced understanding of students’ online learning experience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although many studies have investigated this area, limited information is available regarding the challenges and the specific strategies that students employ to overcome them. Thus, this study attempts to fill in the void. Using a mixed-methods approach, the findings revealed that the online learning challenges of college students varied in terms of type and extent. Their greatest challenge was linked to their learning environment at home, while their least challenge was technological literacy and competency. The findings further revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic had the greatest impact on the quality of the learning experience and students’ mental health. In terms of strategies employed by students, the most frequently used were resource management and utilization, help-seeking, technical aptitude enhancement, time management, and learning environment control. Implications for classroom practice, policy-making, and future research are discussed.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, the world has seen significant changes in the landscape of education as a result of the ever-expanding influence of technology. One such development is the adoption of online learning across different learning contexts, whether formal or informal, academic and non-academic, and residential or remotely. We began to witness schools, teachers, and students increasingly adopt e-learning technologies that allow teachers to deliver instruction interactively, share resources seamlessly, and facilitate student collaboration and interaction (Elaish et al., 2019 ; Garcia et al., 2018 ). Although the efficacy of online learning has long been acknowledged by the education community (Barrot, 2020 , 2021 ; Cavanaugh et al., 2009 ; Kebritchi et al., 2017 ; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 ; Wallace, 2003 ), evidence on the challenges in its implementation continues to build up (e.g., Boelens et al., 2017 ; Rasheed et al., 2020 ).

Recently, the education system has faced an unprecedented health crisis (i.e., COVID-19 pandemic) that has shaken up its foundation. Thus, various governments across the globe have launched a crisis response to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic on education. This response includes, but is not limited to, curriculum revisions, provision for technological resources and infrastructure, shifts in the academic calendar, and policies on instructional delivery and assessment. Inevitably, these developments compelled educational institutions to migrate to full online learning until face-to-face instruction is allowed. The current circumstance is unique as it could aggravate the challenges experienced during online learning due to restrictions in movement and health protocols (Gonzales et al., 2020 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ). Given today’s uncertainties, it is vital to gain a nuanced understanding of students’ online learning experience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, many studies have investigated this area with a focus on students’ mental health (Copeland et al., 2021 ; Fawaz et al., 2021 ), home learning (Suryaman et al., 2020 ), self-regulation (Carter et al., 2020 ), virtual learning environment (Almaiah et al., 2020 ; Hew et al., 2020 ; Tang et al., 2020 ), and students’ overall learning experience (e.g., Adarkwah, 2021 ; Day et al., 2021 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ). There are two key differences that set the current study apart from the previous studies. First, it sheds light on the direct impact of the pandemic on the challenges that students experience in an online learning space. Second, the current study explores students’ coping strategies in this new learning setup. Addressing these areas would shed light on the extent of challenges that students experience in a full online learning space, particularly within the context of the pandemic. Meanwhile, our nuanced understanding of the strategies that students use to overcome their challenges would provide relevant information to school administrators and teachers to better support the online learning needs of students. This information would also be critical in revisiting the typology of strategies in an online learning environment.

Literature review

Education and the covid-19 pandemic.

In December 2019, an outbreak of a novel coronavirus, known as COVID-19, occurred in China and has spread rapidly across the globe within a few months. COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus that attacks the respiratory system (World Health Organization, 2020 ). As of January 2021, COVID-19 has infected 94 million people and has caused 2 million deaths in 191 countries and territories (John Hopkins University, 2021 ). This pandemic has created a massive disruption of the educational systems, affecting over 1.5 billion students. It has forced the government to cancel national examinations and the schools to temporarily close, cease face-to-face instruction, and strictly observe physical distancing. These events have sparked the digital transformation of higher education and challenged its ability to respond promptly and effectively. Schools adopted relevant technologies, prepared learning and staff resources, set systems and infrastructure, established new teaching protocols, and adjusted their curricula. However, the transition was smooth for some schools but rough for others, particularly those from developing countries with limited infrastructure (Pham & Nguyen, 2020 ; Simbulan, 2020 ).

Inevitably, schools and other learning spaces were forced to migrate to full online learning as the world continues the battle to control the vicious spread of the virus. Online learning refers to a learning environment that uses the Internet and other technological devices and tools for synchronous and asynchronous instructional delivery and management of academic programs (Usher & Barak, 2020 ; Huang, 2019 ). Synchronous online learning involves real-time interactions between the teacher and the students, while asynchronous online learning occurs without a strict schedule for different students (Singh & Thurman, 2019 ). Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, online learning has taken the status of interim remote teaching that serves as a response to an exigency. However, the migration to a new learning space has faced several major concerns relating to policy, pedagogy, logistics, socioeconomic factors, technology, and psychosocial factors (Donitsa-Schmidt & Ramot, 2020 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Varea & González-Calvo, 2020 ). With reference to policies, government education agencies and schools scrambled to create fool-proof policies on governance structure, teacher management, and student management. Teachers, who were used to conventional teaching delivery, were also obliged to embrace technology despite their lack of technological literacy. To address this problem, online learning webinars and peer support systems were launched. On the part of the students, dropout rates increased due to economic, psychological, and academic reasons. Academically, although it is virtually possible for students to learn anything online, learning may perhaps be less than optimal, especially in courses that require face-to-face contact and direct interactions (Franchi, 2020 ).

Related studies

Recently, there has been an explosion of studies relating to the new normal in education. While many focused on national policies, professional development, and curriculum, others zeroed in on the specific learning experience of students during the pandemic. Among these are Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) and Fawaz et al. ( 2021 ) who examined the impact of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health and their coping mechanisms. Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) reported that the pandemic adversely affected students’ behavioral and emotional functioning, particularly attention and externalizing problems (i.e., mood and wellness behavior), which were caused by isolation, economic/health effects, and uncertainties. In Fawaz et al.’s ( 2021 ) study, students raised their concerns on learning and evaluation methods, overwhelming task load, technical difficulties, and confinement. To cope with these problems, students actively dealt with the situation by seeking help from their teachers and relatives and engaging in recreational activities. These active-oriented coping mechanisms of students were aligned with Carter et al.’s ( 2020 ), who explored students’ self-regulation strategies.

In another study, Tang et al. ( 2020 ) examined the efficacy of different online teaching modes among engineering students. Using a questionnaire, the results revealed that students were dissatisfied with online learning in general, particularly in the aspect of communication and question-and-answer modes. Nonetheless, the combined model of online teaching with flipped classrooms improved students’ attention, academic performance, and course evaluation. A parallel study was undertaken by Hew et al. ( 2020 ), who transformed conventional flipped classrooms into fully online flipped classes through a cloud-based video conferencing app. Their findings suggested that these two types of learning environments were equally effective. They also offered ways on how to effectively adopt videoconferencing-assisted online flipped classrooms. Unlike the two studies, Suryaman et al. ( 2020 ) looked into how learning occurred at home during the pandemic. Their findings showed that students faced many obstacles in a home learning environment, such as lack of mastery of technology, high Internet cost, and limited interaction/socialization between and among students. In a related study, Kapasia et al. ( 2020 ) investigated how lockdown impacts students’ learning performance. Their findings revealed that the lockdown made significant disruptions in students’ learning experience. The students also reported some challenges that they faced during their online classes. These include anxiety, depression, poor Internet service, and unfavorable home learning environment, which were aggravated when students are marginalized and from remote areas. Contrary to Kapasia et al.’s ( 2020 ) findings, Gonzales et al. ( 2020 ) found that confinement of students during the pandemic had significant positive effects on their performance. They attributed these results to students’ continuous use of learning strategies which, in turn, improved their learning efficiency.

Finally, there are those that focused on students’ overall online learning experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. One such study was that of Singh et al. ( 2020 ), who examined students’ experience during the COVID-19 pandemic using a quantitative descriptive approach. Their findings indicated that students appreciated the use of online learning during the pandemic. However, half of them believed that the traditional classroom setting was more effective than the online learning platform. Methodologically, the researchers acknowledge that the quantitative nature of their study restricts a deeper interpretation of the findings. Unlike the above study, Khalil et al. ( 2020 ) qualitatively explored the efficacy of synchronized online learning in a medical school in Saudi Arabia. The results indicated that students generally perceive synchronous online learning positively, particularly in terms of time management and efficacy. However, they also reported technical (internet connectivity and poor utility of tools), methodological (content delivery), and behavioral (individual personality) challenges. Their findings also highlighted the failure of the online learning environment to address the needs of courses that require hands-on practice despite efforts to adopt virtual laboratories. In a parallel study, Adarkwah ( 2021 ) examined students’ online learning experience during the pandemic using a narrative inquiry approach. The findings indicated that Ghanaian students considered online learning as ineffective due to several challenges that they encountered. Among these were lack of social interaction among students, poor communication, lack of ICT resources, and poor learning outcomes. More recently, Day et al. ( 2021 ) examined the immediate impact of COVID-19 on students’ learning experience. Evidence from six institutions across three countries revealed some positive experiences and pre-existing inequities. Among the reported challenges are lack of appropriate devices, poor learning space at home, stress among students, and lack of fieldwork and access to laboratories.

Although there are few studies that report the online learning challenges that higher education students experience during the pandemic, limited information is available regarding the specific strategies that they use to overcome them. It is in this context that the current study was undertaken. This mixed-methods study investigates students’ online learning experience in higher education. Specifically, the following research questions are addressed: (1) What is the extent of challenges that students experience in an online learning environment? (2) How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact the online learning challenges that students experience? (3) What strategies did students use to overcome the challenges?

Conceptual framework

The typology of challenges examined in this study is largely based on Rasheed et al.’s ( 2020 ) review of students’ experience in an online learning environment. These challenges are grouped into five general clusters, namely self-regulation (SRC), technological literacy and competency (TLCC), student isolation (SIC), technological sufficiency (TSC), and technological complexity (TCC) challenges (Rasheed et al., 2020 , p. 5). SRC refers to a set of behavior by which students exercise control over their emotions, actions, and thoughts to achieve learning objectives. TLCC relates to a set of challenges about students’ ability to effectively use technology for learning purposes. SIC relates to the emotional discomfort that students experience as a result of being lonely and secluded from their peers. TSC refers to a set of challenges that students experience when accessing available online technologies for learning. Finally, there is TCC which involves challenges that students experience when exposed to complex and over-sufficient technologies for online learning.

To extend Rasheed et al. ( 2020 ) categories and to cover other potential challenges during online classes, two more clusters were added, namely learning resource challenges (LRC) and learning environment challenges (LEC) (Buehler, 2004 ; Recker et al., 2004 ; Seplaki et al., 2014 ; Xue et al., 2020 ). LRC refers to a set of challenges that students face relating to their use of library resources and instructional materials, whereas LEC is a set of challenges that students experience related to the condition of their learning space that shapes their learning experiences, beliefs, and attitudes. Since learning environment at home and learning resources available to students has been reported to significantly impact the quality of learning and their achievement of learning outcomes (Drane et al., 2020 ; Suryaman et al., 2020 ), the inclusion of LRC and LEC would allow us to capture other important challenges that students experience during the pandemic, particularly those from developing regions. This comprehensive list would provide us a clearer and detailed picture of students’ experiences when engaged in online learning in an emergency. Given the restrictions in mobility at macro and micro levels during the pandemic, it is also expected that such conditions would aggravate these challenges. Therefore, this paper intends to understand these challenges from students’ perspectives since they are the ones that are ultimately impacted when the issue is about the learning experience. We also seek to explore areas that provide inconclusive findings, thereby setting the path for future research.

Material and methods

The present study adopted a descriptive, mixed-methods approach to address the research questions. This approach allowed the researchers to collect complex data about students’ experience in an online learning environment and to clearly understand the phenomena from their perspective.

Participants

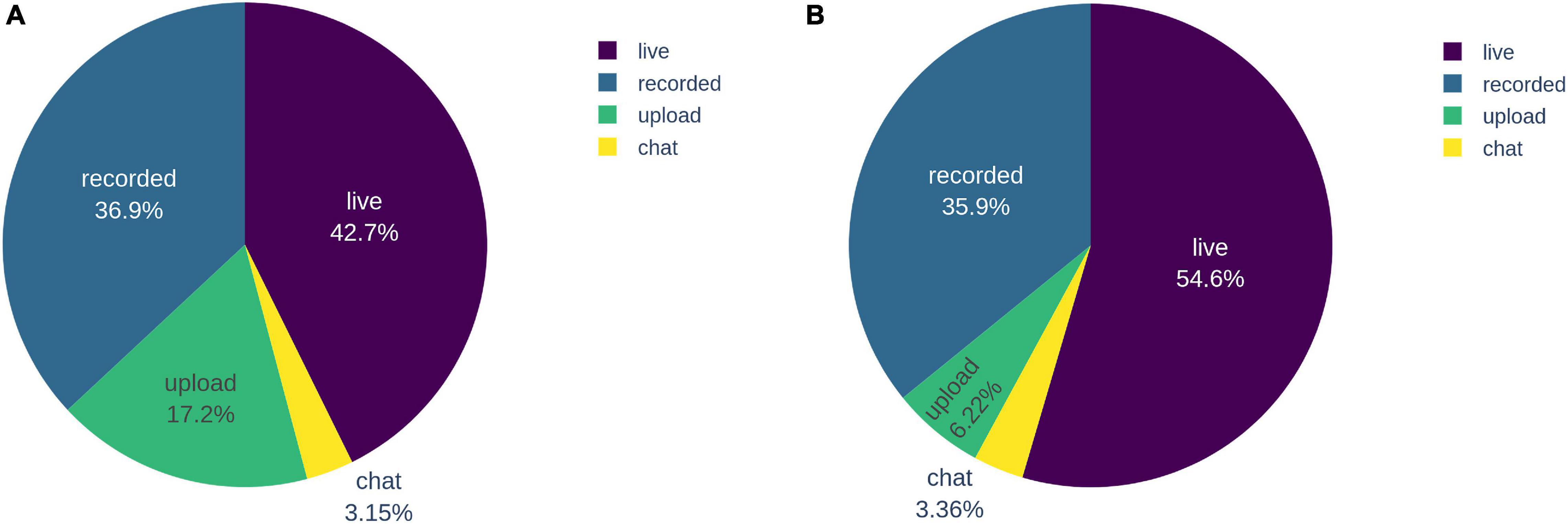

This study involved 200 (66 male and 134 female) students from a private higher education institution in the Philippines. These participants were Psychology, Physical Education, and Sports Management majors whose ages ranged from 17 to 25 ( x ̅ = 19.81; SD = 1.80). The students have been engaged in online learning for at least two terms in both synchronous and asynchronous modes. The students belonged to low- and middle-income groups but were equipped with the basic online learning equipment (e.g., computer, headset, speakers) and computer skills necessary for their participation in online classes. Table Table1 1 shows the primary and secondary platforms that students used during their online classes. The primary platforms are those that are formally adopted by teachers and students in a structured academic context, whereas the secondary platforms are those that are informally and spontaneously used by students and teachers for informal learning and to supplement instructional delivery. Note that almost all students identified MS Teams as their primary platform because it is the official learning management system of the university.

Participants’ Online Learning Platforms

| Learning Platforms | Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Supplementary | |||

| Blackboard | - | - | 1 | 0.50 |

| Canvas | - | - | 1 | 0.50 |

| Edmodo | - | - | 1 | 0.50 |

| 9 | 4.50 | 170 | 85.00 | |

| Google Classroom | 5 | 2.50 | 15 | 7.50 |

| Moodle | - | - | 7 | 3.50 |

| MS Teams | 184 | 92.00 | - | - |

| Schoology | 1 | 0.50 | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | |

| Zoom | 1 | 0.50 | 5 | 2.50 |

| 200 | 100.00 | 200 | 100.00 | |

Informed consent was sought from the participants prior to their involvement. Before students signed the informed consent form, they were oriented about the objectives of the study and the extent of their involvement. They were also briefed about the confidentiality of information, their anonymity, and their right to refuse to participate in the investigation. Finally, the participants were informed that they would incur no additional cost from their participation.

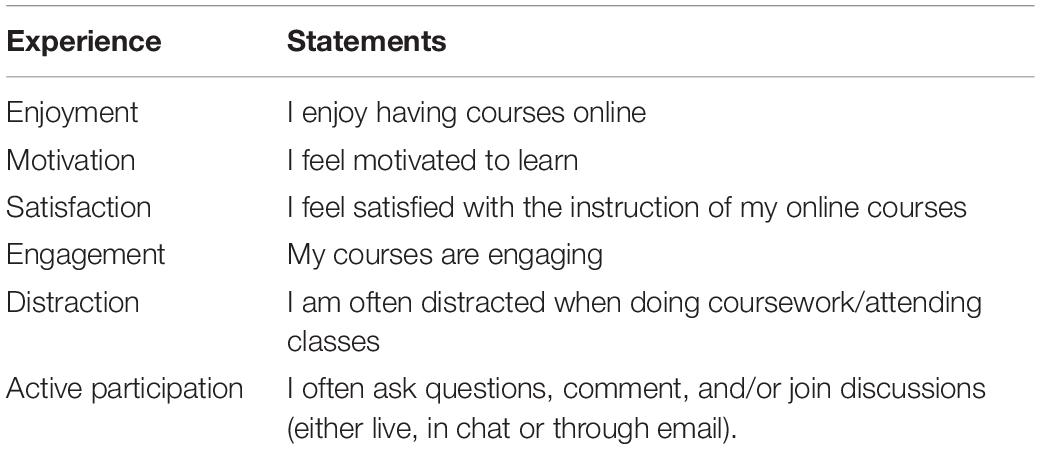

Instrument and data collection

The data were collected using a retrospective self-report questionnaire and a focused group discussion (FGD). A self-report questionnaire was considered appropriate because the indicators relate to affective responses and attitude (Araujo et al., 2017 ; Barrot, 2016 ; Spector, 1994 ). Although the participants may tell more than what they know or do in a self-report survey (Matsumoto, 1994 ), this challenge was addressed by explaining to them in detail each of the indicators and using methodological triangulation through FGD. The questionnaire was divided into four sections: (1) participant’s personal information section, (2) the background information on the online learning environment, (3) the rating scale section for the online learning challenges, (4) the open-ended section. The personal information section asked about the students’ personal information (name, school, course, age, and sex), while the background information section explored the online learning mode and platforms (primary and secondary) used in class, and students’ length of engagement in online classes. The rating scale section contained 37 items that relate to SRC (6 items), TLCC (10 items), SIC (4 items), TSC (6 items), TCC (3 items), LRC (4 items), and LEC (4 items). The Likert scale uses six scores (i.e., 5– to a very great extent , 4– to a great extent , 3– to a moderate extent , 2– to some extent , 1– to a small extent , and 0 –not at all/negligible ) assigned to each of the 37 items. Finally, the open-ended questions asked about other challenges that students experienced, the impact of the pandemic on the intensity or extent of the challenges they experienced, and the strategies that the participants employed to overcome the eight different types of challenges during online learning. Two experienced educators and researchers reviewed the questionnaire for clarity, accuracy, and content and face validity. The piloting of the instrument revealed that the tool had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.96).

The FGD protocol contains two major sections: the participants’ background information and the main questions. The background information section asked about the students’ names, age, courses being taken, online learning mode used in class. The items in the main questions section covered questions relating to the students’ overall attitude toward online learning during the pandemic, the reasons for the scores they assigned to each of the challenges they experienced, the impact of the pandemic on students’ challenges, and the strategies they employed to address the challenges. The same experts identified above validated the FGD protocol.

Both the questionnaire and the FGD were conducted online via Google survey and MS Teams, respectively. It took approximately 20 min to complete the questionnaire, while the FGD lasted for about 90 min. Students were allowed to ask for clarification and additional explanations relating to the questionnaire content, FGD, and procedure. Online surveys and interview were used because of the ongoing lockdown in the city. For the purpose of triangulation, 20 (10 from Psychology and 10 from Physical Education and Sports Management) randomly selected students were invited to participate in the FGD. Two separate FGDs were scheduled for each group and were facilitated by researcher 2 and researcher 3, respectively. The interviewers ensured that the participants were comfortable and open to talk freely during the FGD to avoid social desirability biases (Bergen & Labonté, 2020 ). These were done by informing the participants that there are no wrong responses and that their identity and responses would be handled with the utmost confidentiality. With the permission of the participants, the FGD was recorded to ensure that all relevant information was accurately captured for transcription and analysis.

Data analysis

To address the research questions, we used both quantitative and qualitative analyses. For the quantitative analysis, we entered all the data into an excel spreadsheet. Then, we computed the mean scores ( M ) and standard deviations ( SD ) to determine the level of challenges experienced by students during online learning. The mean score for each descriptor was interpreted using the following scheme: 4.18 to 5.00 ( to a very great extent ), 3.34 to 4.17 ( to a great extent ), 2.51 to 3.33 ( to a moderate extent ), 1.68 to 2.50 ( to some extent ), 0.84 to 1.67 ( to a small extent ), and 0 to 0.83 ( not at all/negligible ). The equal interval was adopted because it produces more reliable and valid information than other types of scales (Cicchetti et al., 2006 ).

For the qualitative data, we analyzed the students’ responses in the open-ended questions and the transcribed FGD using the predetermined categories in the conceptual framework. Specifically, we used multilevel coding in classifying the codes from the transcripts (Birks & Mills, 2011 ). To do this, we identified the relevant codes from the responses of the participants and categorized these codes based on the similarities or relatedness of their properties and dimensions. Then, we performed a constant comparative and progressive analysis of cases to allow the initially identified subcategories to emerge and take shape. To ensure the reliability of the analysis, two coders independently analyzed the qualitative data. Both coders familiarize themselves with the purpose, research questions, research method, and codes and coding scheme of the study. They also had a calibration session and discussed ways on how they could consistently analyze the qualitative data. Percent of agreement between the two coders was 86 percent. Any disagreements in the analysis were discussed by the coders until an agreement was achieved.

This study investigated students’ online learning experience in higher education within the context of the pandemic. Specifically, we identified the extent of challenges that students experienced, how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their online learning experience, and the strategies that they used to confront these challenges.

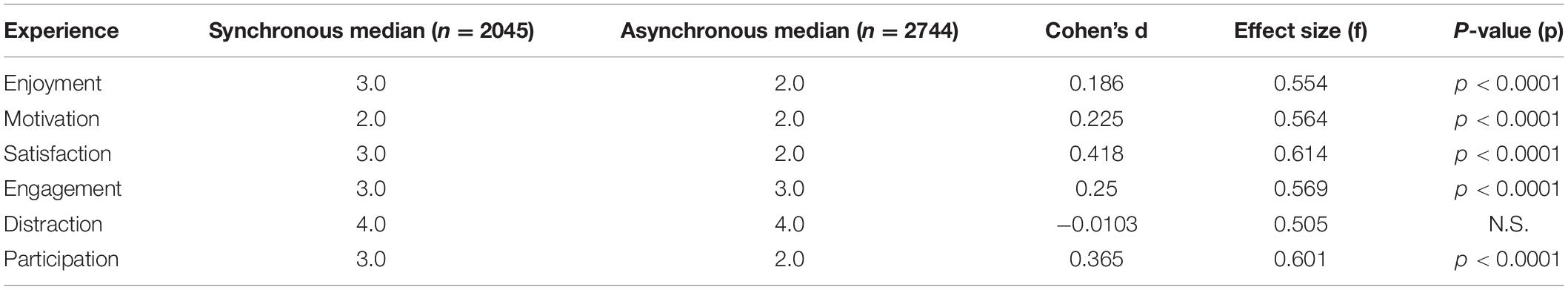

The extent of students’ online learning challenges

Table Table2 2 presents the mean scores and SD for the extent of challenges that students’ experienced during online learning. Overall, the students experienced the identified challenges to a moderate extent ( x ̅ = 2.62, SD = 1.03) with scores ranging from x ̅ = 1.72 ( to some extent ) to x ̅ = 3.58 ( to a great extent ). More specifically, the greatest challenge that students experienced was related to the learning environment ( x ̅ = 3.49, SD = 1.27), particularly on distractions at home, limitations in completing the requirements for certain subjects, and difficulties in selecting the learning areas and study schedule. It is, however, found that the least challenge was on technological literacy and competency ( x ̅ = 2.10, SD = 1.13), particularly on knowledge and training in the use of technology, technological intimidation, and resistance to learning technologies. Other areas that students experienced the least challenge are Internet access under TSC and procrastination under SRC. Nonetheless, nearly half of the students’ responses per indicator rated the challenges they experienced as moderate (14 of the 37 indicators), particularly in TCC ( x ̅ = 2.51, SD = 1.31), SIC ( x ̅ = 2.77, SD = 1.34), and LRC ( x ̅ = 2.93, SD = 1.31).

The Extent of Students’ Challenges during the Interim Online Learning

| CHALLENGES | ||

|---|---|---|

| Self-regulation challenges (SRC) | 2.37 | 1.16 |

| 1. I delay tasks related to my studies so that they are either not fully completed by their deadline or had to be rushed to be completed. | 1.84 | 1.47 |

| 2. I fail to get appropriate help during online classes. | 2.04 | 1.44 |

| 3. I lack the ability to control my own thoughts, emotions, and actions during online classes. | 2.51 | 1.65 |

| 4. I have limited preparation before an online class. | 2.68 | 1.54 |

| 5. I have poor time management skills during online classes. | 2.50 | 1.53 |

| 6. I fail to properly use online peer learning strategies (i.e., learning from one another to better facilitate learning such as peer tutoring, group discussion, and peer feedback). | 2.34 | 1.50 |

| Technological literacy and competency challenges (TLCC) | 2.10 | 1.13 |

| 7. I lack competence and proficiency in using various interfaces or systems that allow me to control a computer or another embedded system for studying. | 2.05 | 1.39 |

| 8. I resist learning technology. | 1.89 | 1.46 |

| 9. I am distracted by an overly complex technology. | 2.44 | 1.43 |

| 10. I have difficulties in learning a new technology. | 2.06 | 1.50 |

| 11. I lack the ability to effectively use technology to facilitate learning. | 2.08 | 1.51 |

| 12. I lack knowledge and training in the use of technology. | 1.76 | 1.43 |

| 13. I am intimidated by the technologies used for learning. | 1.89 | 1.44 |

| 14. I resist and/or am confused when getting appropriate help during online classes. | 2.19 | 1.52 |

| 15. I have poor understanding of directions and expectations during online learning. | 2.16 | 1.56 |

| 16. I perceive technology as a barrier to getting help from others during online classes. | 2.47 | 1.43 |

| Student isolation challenges (SIC) | 2.77 | 1.34 |

| 17. I feel emotionally disconnected or isolated during online classes. | 2.71 | 1.58 |

| 18. I feel disinterested during online class. | 2.54 | 1.53 |

| 19. I feel unease and uncomfortable in using video projection, microphones, and speakers. | 2.90 | 1.57 |

| 20. I feel uncomfortable being the center of attention during online classes. | 2.93 | 1.67 |

| Technological sufficiency challenges (TSC) | 2.31 | 1.29 |

| 21. I have an insufficient access to learning technology. | 2.27 | 1.52 |

| 22. I experience inequalities with regard to to and use of technologies during online classes because of my socioeconomic, physical, and psychological condition. | 2.34 | 1.68 |

| 23. I have an outdated technology. | 2.04 | 1.62 |

| 24. I do not have Internet access during online classes. | 1.72 | 1.65 |

| 25. I have low bandwidth and slow processing speeds. | 2.66 | 1.62 |

| 26. I experience technical difficulties in completing my assignments. | 2.84 | 1.54 |

| Technological complexity challenges (TCC) | 2.51 | 1.31 |

| 27. I am distracted by the complexity of the technology during online classes. | 2.34 | 1.46 |

| 28. I experience difficulties in using complex technology. | 2.33 | 1.51 |

| 29. I experience difficulties when using longer videos for learning. | 2.87 | 1.48 |

| Learning resource challenges (LRC) | 2.93 | 1.31 |

| 30. I have an insufficient access to library resources. | 2.86 | 1.72 |

| 31. I have an insufficient access to laboratory equipment and materials. | 3.16 | 1.71 |

| 32. I have limited access to textbooks, worksheets, and other instructional materials. | 2.63 | 1.57 |

| 33. I experience financial challenges when accessing learning resources and technology. | 3.07 | 1.57 |

| Learning environment challenges (LEC) | 3.49 | 1.27 |

| 34. I experience online distractions such as social media during online classes. | 3.20 | 1.58 |

| 35. I experience distractions at home as a learning environment. | 3.55 | 1.54 |

| 36. I have difficulties in selecting the best time and area for learning at home. | 3.40 | 1.58 |

| 37. Home set-up limits the completion of certain requirements for my subject (e.g., laboratory and physical activities). | 3.58 | 1.52 |

| AVERAGE | 2.62 | 1.03 |

Out of 200 students, 181 responded to the question about other challenges that they experienced. Most of their responses were already covered by the seven predetermined categories, except for 18 responses related to physical discomfort ( N = 5) and financial challenges ( N = 13). For instance, S108 commented that “when it comes to eyes and head, my eyes and head get ache if the session of class was 3 h straight in front of my gadget.” In the same vein, S194 reported that “the long exposure to gadgets especially laptop, resulting in body pain & headaches.” With reference to physical financial challenges, S66 noted that “not all the time I have money to load”, while S121 claimed that “I don't know until when are we going to afford budgeting our money instead of buying essentials.”

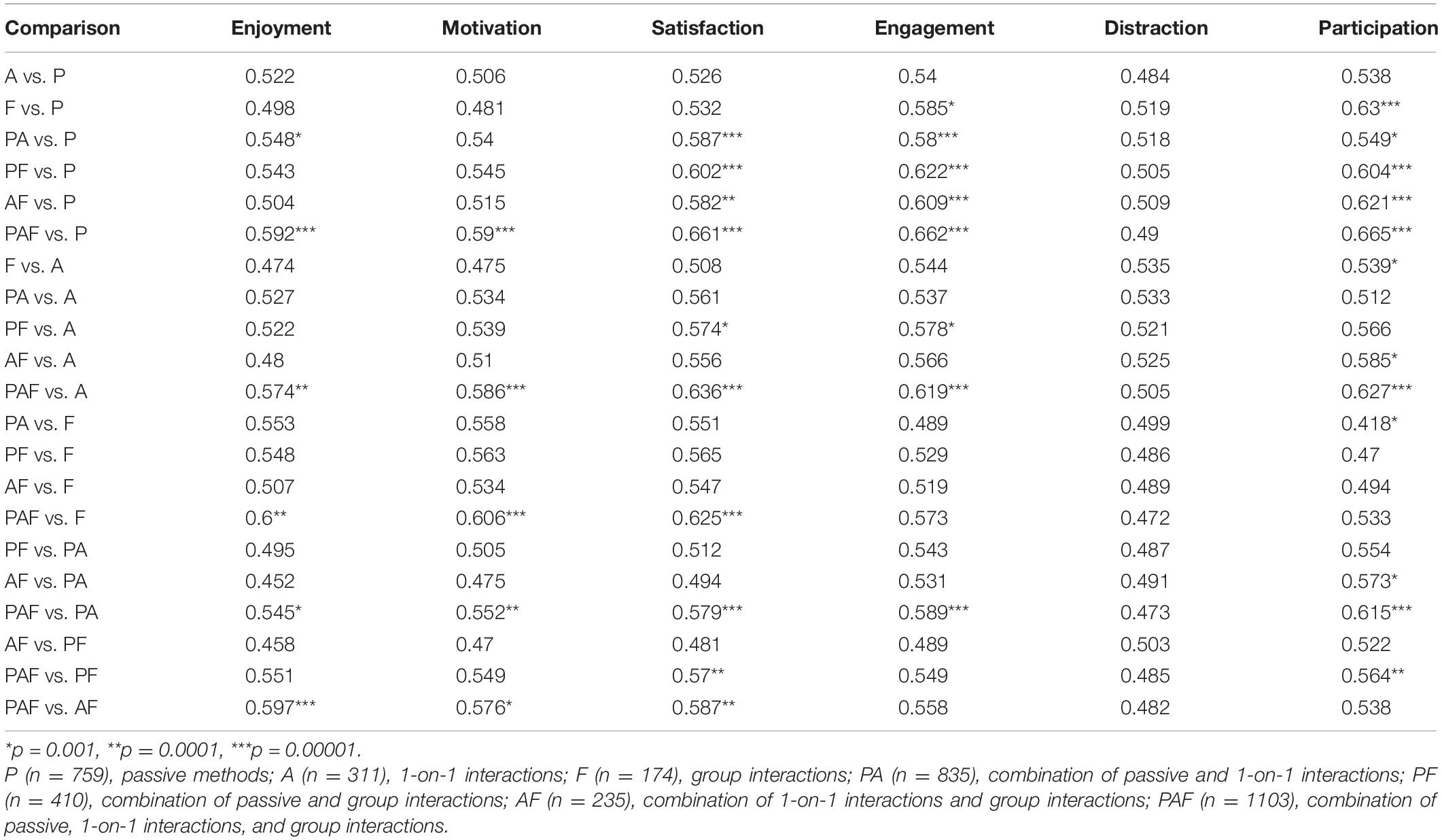

Impact of the pandemic on students’ online learning challenges

Another objective of this study was to identify how COVID-19 influenced the online learning challenges that students experienced. As shown in Table Table3, 3 , most of the students’ responses were related to teaching and learning quality ( N = 86) and anxiety and other mental health issues ( N = 52). Regarding the adverse impact on teaching and learning quality, most of the comments relate to the lack of preparation for the transition to online platforms (e.g., S23, S64), limited infrastructure (e.g., S13, S65, S99, S117), and poor Internet service (e.g., S3, S9, S17, S41, S65, S99). For the anxiety and mental health issues, most students reported that the anxiety, boredom, sadness, and isolation they experienced had adversely impacted the way they learn (e.g., S11, S130), completing their tasks/activities (e.g., S56, S156), and their motivation to continue studying (e.g., S122, S192). The data also reveal that COVID-19 aggravated the financial difficulties experienced by some students ( N = 16), consequently affecting their online learning experience. This financial impact mainly revolved around the lack of funding for their online classes as a result of their parents’ unemployment and the high cost of Internet data (e.g., S18, S113, S167). Meanwhile, few concerns were raised in relation to COVID-19’s impact on mobility ( N = 7) and face-to-face interactions ( N = 7). For instance, some commented that the lack of face-to-face interaction with her classmates had a detrimental effect on her learning (S46) and socialization skills (S36), while others reported that restrictions in mobility limited their learning experience (S78, S110). Very few comments were related to no effect ( N = 4) and positive effect ( N = 2). The above findings suggest the pandemic had additive adverse effects on students’ online learning experience.

Summary of students’ responses on the impact of COVID-19 on their online learning experience

| Areas | Sample Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Reduces the quality of learning experience | 86 | (S13) (S65) (S118) |

| Causes anxiety and other mental health issues | 52 | (S11) (S56) (S192) |

| Aggravates financial problems | 16 | (S18) (S167) |

| Limits interaction | 7 | (S36) (S46) |

| Restricts mobility | 7 | (S78) (S110) |

| No effect | 4 | (S100) (S168) |

| Positive effect | 2 | (S35) (S112) |

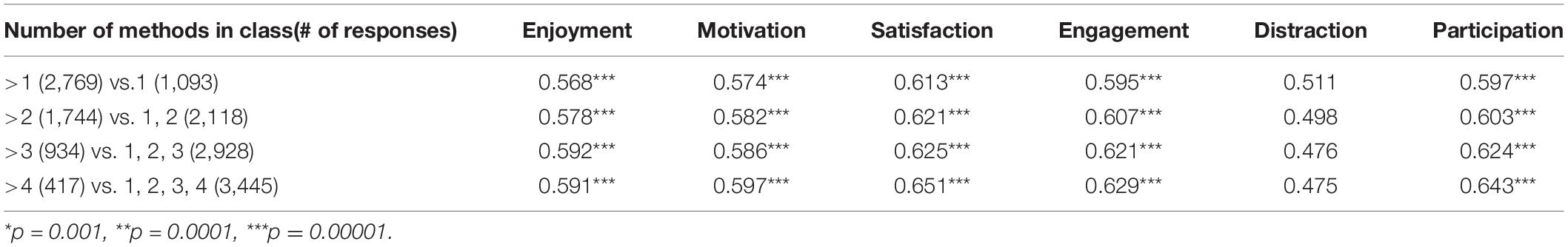

Students’ strategies to overcome challenges in an online learning environment

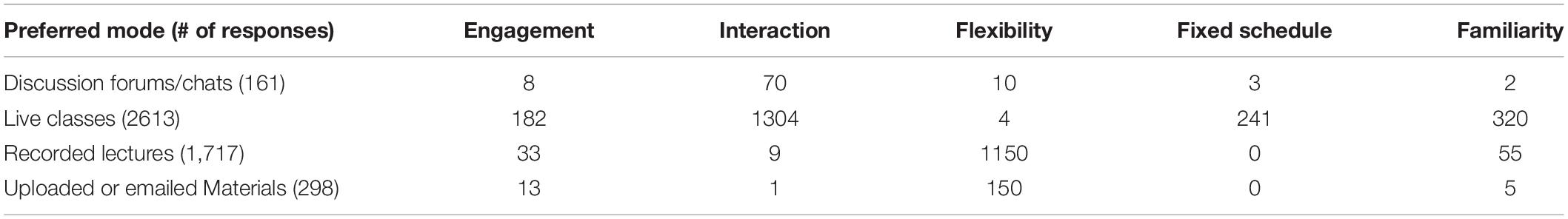

The third objective of this study is to identify the strategies that students employed to overcome the different online learning challenges they experienced. Table Table4 4 presents that the most commonly used strategies used by students were resource management and utilization ( N = 181), help-seeking ( N = 155), technical aptitude enhancement ( N = 122), time management ( N = 98), and learning environment control ( N = 73). Not surprisingly, the top two strategies were also the most consistently used across different challenges. However, looking closely at each of the seven challenges, the frequency of using a particular strategy varies. For TSC and LRC, the most frequently used strategy was resource management and utilization ( N = 52, N = 89, respectively), whereas technical aptitude enhancement was the students’ most preferred strategy to address TLCC ( N = 77) and TCC ( N = 38). In the case of SRC, SIC, and LEC, the most frequently employed strategies were time management ( N = 71), psychological support ( N = 53), and learning environment control ( N = 60). In terms of consistency, help-seeking appears to be the most consistent across the different challenges in an online learning environment. Table Table4 4 further reveals that strategies used by students within a specific type of challenge vary.

Students’ Strategies to Overcome Online Learning Challenges

| Strategies | SRC | TLCC | SIC | TSC | TCC | LRC | LEC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation | 7 | 1 | 11 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 17 | 60 |

| Cognitive aptitude enhancement | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 13 |

| Concentration and focus | 13 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 43 |

| Focus and concentration | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Goal-setting | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| Help-seeking | 13 | 42 | 2 | 36 | 16 | 28 | 18 | 155 |

| Learning environment control | 1 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 60 | 73 |

| Motivation | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| Optimism | 4 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 47 |

| Peer learning | 3 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Psychosocial support | 3 | 0 | 53 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 57 |

| Reflection | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Relaxation and recreation | 16 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 37 |

| Resource management & utilization | 3 | 11 | 0 | 52 | 20 | 89 | 6 | 181 |

| Self-belief | 0 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 |

| Self-discipline | 12 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 32 |

| Self-study | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Technical aptitude enhancement | 0 | 77 | 0 | 7 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 122 |

| Thought control | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 13 |

| Time management | 71 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 98 |

| Transcendental strategies | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Discussion and conclusions

The current study explores the challenges that students experienced in an online learning environment and how the pandemic impacted their online learning experience. The findings revealed that the online learning challenges of students varied in terms of type and extent. Their greatest challenge was linked to their learning environment at home, while their least challenge was technological literacy and competency. Based on the students’ responses, their challenges were also found to be aggravated by the pandemic, especially in terms of quality of learning experience, mental health, finances, interaction, and mobility. With reference to previous studies (i.e., Adarkwah, 2021 ; Copeland et al., 2021 ; Day et al., 2021 ; Fawaz et al., 2021 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ), the current study has complemented their findings on the pedagogical, logistical, socioeconomic, technological, and psychosocial online learning challenges that students experience within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, this study extended previous studies and our understanding of students’ online learning experience by identifying both the presence and extent of online learning challenges and by shedding light on the specific strategies they employed to overcome them.

Overall findings indicate that the extent of challenges and strategies varied from one student to another. Hence, they should be viewed as a consequence of interaction several many factors. Students’ responses suggest that their online learning challenges and strategies were mediated by the resources available to them, their interaction with their teachers and peers, and the school’s existing policies and guidelines for online learning. In the context of the pandemic, the imposed lockdowns and students’ socioeconomic condition aggravated the challenges that students experience.

While most studies revealed that technology use and competency were the most common challenges that students face during the online classes (see Rasheed et al., 2020 ), the case is a bit different in developing countries in times of pandemic. As the findings have shown, the learning environment is the greatest challenge that students needed to hurdle, particularly distractions at home (e.g., noise) and limitations in learning space and facilities. This data suggests that online learning challenges during the pandemic somehow vary from the typical challenges that students experience in a pre-pandemic online learning environment. One possible explanation for this result is that restriction in mobility may have aggravated this challenge since they could not go to the school or other learning spaces beyond the vicinity of their respective houses. As shown in the data, the imposition of lockdown restricted students’ learning experience (e.g., internship and laboratory experiments), limited their interaction with peers and teachers, caused depression, stress, and anxiety among students, and depleted the financial resources of those who belong to lower-income group. All of these adversely impacted students’ learning experience. This finding complemented earlier reports on the adverse impact of lockdown on students’ learning experience and the challenges posed by the home learning environment (e.g., Day et al., 2021 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ). Nonetheless, further studies are required to validate the impact of restrictions on mobility on students’ online learning experience. The second reason that may explain the findings relates to students’ socioeconomic profile. Consistent with the findings of Adarkwah ( 2021 ) and Day et al. ( 2021 ), the current study reveals that the pandemic somehow exposed the many inequities in the educational systems within and across countries. In the case of a developing country, families from lower socioeconomic strata (as in the case of the students in this study) have limited learning space at home, access to quality Internet service, and online learning resources. This is the reason the learning environment and learning resources recorded the highest level of challenges. The socioeconomic profile of the students (i.e., low and middle-income group) is the same reason financial problems frequently surfaced from their responses. These students frequently linked the lack of financial resources to their access to the Internet, educational materials, and equipment necessary for online learning. Therefore, caution should be made when interpreting and extending the findings of this study to other contexts, particularly those from higher socioeconomic strata.

Among all the different online learning challenges, the students experienced the least challenge on technological literacy and competency. This is not surprising considering a plethora of research confirming Gen Z students’ (born since 1996) high technological and digital literacy (Barrot, 2018 ; Ng, 2012 ; Roblek et al., 2019 ). Regarding the impact of COVID-19 on students’ online learning experience, the findings reveal that teaching and learning quality and students’ mental health were the most affected. The anxiety that students experienced does not only come from the threats of COVID-19 itself but also from social and physical restrictions, unfamiliarity with new learning platforms, technical issues, and concerns about financial resources. These findings are consistent with that of Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) and Fawaz et al. ( 2021 ), who reported the adverse effects of the pandemic on students’ mental and emotional well-being. This data highlights the need to provide serious attention to the mediating effects of mental health, restrictions in mobility, and preparedness in delivering online learning.

Nonetheless, students employed a variety of strategies to overcome the challenges they faced during online learning. For instance, to address the home learning environment problems, students talked to their family (e.g., S12, S24), transferred to a quieter place (e.g., S7, S 26), studied at late night where all family members are sleeping already (e.g., S51), and consulted with their classmates and teachers (e.g., S3, S9, S156, S193). To overcome the challenges in learning resources, students used the Internet (e.g., S20, S27, S54, S91), joined Facebook groups that share free resources (e.g., S5), asked help from family members (e.g., S16), used resources available at home (e.g., S32), and consulted with the teachers (e.g., S124). The varying strategies of students confirmed earlier reports on the active orientation that students take when faced with academic- and non-academic-related issues in an online learning space (see Fawaz et al., 2021 ). The specific strategies that each student adopted may have been shaped by different factors surrounding him/her, such as available resources, student personality, family structure, relationship with peers and teacher, and aptitude. To expand this study, researchers may further investigate this area and explore how and why different factors shape their use of certain strategies.

Several implications can be drawn from the findings of this study. First, this study highlighted the importance of emergency response capability and readiness of higher education institutions in case another crisis strikes again. Critical areas that need utmost attention include (but not limited to) national and institutional policies, protocol and guidelines, technological infrastructure and resources, instructional delivery, staff development, potential inequalities, and collaboration among key stakeholders (i.e., parents, students, teachers, school leaders, industry, government education agencies, and community). Second, the findings have expanded our understanding of the different challenges that students might confront when we abruptly shift to full online learning, particularly those from countries with limited resources, poor Internet infrastructure, and poor home learning environment. Schools with a similar learning context could use the findings of this study in developing and enhancing their respective learning continuity plans to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic. This study would also provide students relevant information needed to reflect on the possible strategies that they may employ to overcome the challenges. These are critical information necessary for effective policymaking, decision-making, and future implementation of online learning. Third, teachers may find the results useful in providing proper interventions to address the reported challenges, particularly in the most critical areas. Finally, the findings provided us a nuanced understanding of the interdependence of learning tools, learners, and learning outcomes within an online learning environment; thus, giving us a multiperspective of hows and whys of a successful migration to full online learning.

Some limitations in this study need to be acknowledged and addressed in future studies. One limitation of this study is that it exclusively focused on students’ perspectives. Future studies may widen the sample by including all other actors taking part in the teaching–learning process. Researchers may go deeper by investigating teachers’ views and experience to have a complete view of the situation and how different elements interact between them or affect the others. Future studies may also identify some teacher-related factors that could influence students’ online learning experience. In the case of students, their age, sex, and degree programs may be examined in relation to the specific challenges and strategies they experience. Although the study involved a relatively large sample size, the participants were limited to college students from a Philippine university. To increase the robustness of the findings, future studies may expand the learning context to K-12 and several higher education institutions from different geographical regions. As a final note, this pandemic has undoubtedly reshaped and pushed the education system to its limits. However, this unprecedented event is the same thing that will make the education system stronger and survive future threats.

Authors’ contributions

Jessie Barrot led the planning, prepared the instrument, wrote the report, and processed and analyzed data. Ian Llenares participated in the planning, fielded the instrument, processed and analyzed data, reviewed the instrument, and contributed to report writing. Leo del Rosario participated in the planning, fielded the instrument, processed and analyzed data, reviewed the instrument, and contributed to report writing.

No funding was received in the conduct of this study.

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

The study has undergone appropriate ethics protocol.

Informed consent was sought from the participants.

Authors consented the publication. Participants consented to publication as long as confidentiality is observed.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Adarkwah MA. “I’m not against online teaching, but what about us?”: ICT in Ghana post Covid-19. Education and Information Technologies. 2021; 26 (2):1665–1685. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10331-z. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Almaiah MA, Al-Khasawneh A, Althunibat A. Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies. 2020; 25 :5261–5280. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10219-y. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Araujo T, Wonneberger A, Neijens P, de Vreese C. How much time do you spend online? Understanding and improving the accuracy of self-reported measures of Internet use. Communication Methods and Measures. 2017; 11 (3):173–190. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2017.1317337. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrot, J. S. (2016). Using Facebook-based e-portfolio in ESL writing classrooms: Impact and challenges. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29 (3), 286–301.

- Barrot, J. S. (2018). Facebook as a learning environment for language teaching and learning: A critical analysis of the literature from 2010 to 2017. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34 (6), 863–875.

- Barrot, J. S. (2020). Scientific mapping of social media in education: A decade of exponential growth. Journal of Educational Computing Research . 10.1177/0735633120972010.

- Barrot, J. S. (2021). Social media as a language learning environment: A systematic review of the literature (2008–2019). Computer Assisted Language Learning . 10.1080/09588221.2021.1883673.

- Bergen N, Labonté R. “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: Detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2020; 30 (5):783–792. doi: 10.1177/1049732319889354. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2011). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage.

- Boelens R, De Wever B, Voet M. Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review. 2017; 22 :1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2017.06.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buehler MA. Where is the library in course management software? Journal of Library Administration. 2004; 41 (1–2):75–84. doi: 10.1300/J111v41n01_07. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter RA, Jr, Rice M, Yang S, Jackson HA. Self-regulated learning in online learning environments: Strategies for remote learning. Information and Learning Sciences. 2020; 121 (5/6):321–329. doi: 10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0114. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cavanaugh CS, Barbour MK, Clark T. Research and practice in K-12 online learning: A review of open access literature. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 2009; 10 (1):1–22. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v10i1.607. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cicchetti D, Bronen R, Spencer S, Haut S, Berg A, Oliver P, Tyrer P. Rating scales, scales of measurement, issues of reliability: Resolving some critical issues for clinicians and researchers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006; 194 (8):557–564. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000230392.83607.c5. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Copeland WE, McGinnis E, Bai Y, Adams Z, Nardone H, Devadanam V, Hudziak JJ. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021; 60 (1):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Day T, Chang ICC, Chung CKL, Doolittle WE, Housel J, McDaniel PN. The immediate impact of COVID-19 on postsecondary teaching and learning. The Professional Geographer. 2021; 73 (1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2020.1823864. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donitsa-Schmidt S, Ramot R. Opportunities and challenges: Teacher education in Israel in the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Education for Teaching. 2020; 46 (4):586–595. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1799708. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drane, C., Vernon, L., & O’Shea, S. (2020). The impact of ‘learning at home’on the educational outcomes of vulnerable children in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Literature Review Prepared by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. Curtin University, Australia.

- Elaish M, Shuib L, Ghani N, Yadegaridehkordi E. Mobile English language learning (MELL): A literature review. Educational Review. 2019; 71 (2):257–276. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2017.1382445. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fawaz, M., Al Nakhal, M., & Itani, M. (2021). COVID-19 quarantine stressors and management among Lebanese students: A qualitative study. Current Psychology , 1–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Franchi T. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on current anatomy education and future careers: A student’s perspective. Anatomical Sciences Education. 2020; 13 (3):312–315. doi: 10.1002/ase.1966. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garcia R, Falkner K, Vivian R. Systematic literature review: Self-regulated learning strategies using e-learning tools for computer science. Computers & Education. 2018; 123 :150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.006. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gonzalez T, De La Rubia MA, Hincz KP, Comas-Lopez M, Subirats L, Fort S, Sacha GM. Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15 (10):e0239490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239490. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hew KF, Jia C, Gonda DE, Bai S. Transitioning to the “new normal” of learning in unpredictable times: Pedagogical practices and learning performance in fully online flipped classrooms. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 2020; 17 (1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00234-x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang Q. Comparing teacher’s roles of F2F learning and online learning in a blended English course. Computer Assisted Language Learning. 2019; 32 (3):190–209. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2018.1540434. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- John Hopkins University. (2021). Global map . https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

- Kapasia N, Paul P, Roy A, Saha J, Zaveri A, Mallick R, Chouhan P. Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal. India. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020; 116 :105194. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105194. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kebritchi M, Lipschuetz A, Santiague L. Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. 2017; 46 (1):4–29. doi: 10.1177/0047239516661713. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Khalil R, Mansour AE, Fadda WA, Almisnid K, Aldamegh M, Al-Nafeesah A, Al-Wutayd O. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Medical Education. 2020; 20 (1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Matsumoto K. Introspection, verbal reports and second language learning strategy research. Canadian Modern Language Review. 1994; 50 (2):363–386. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.50.2.363. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ng W. Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education. 2012; 59 (3):1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.016. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pham T, Nguyen H. COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities for Vietnamese higher education. Higher Education in Southeast Asia and beyond. 2020; 8 :22–24. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rasheed RA, Kamsin A, Abdullah NA. Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Computers & Education. 2020; 144 :103701. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103701. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Recker MM, Dorward J, Nelson LM. Discovery and use of online learning resources: Case study findings. Educational Technology & Society. 2004; 7 (2):93–104. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roblek V, Mesko M, Dimovski V, Peterlin J. Smart technologies as social innovation and complex social issues of the Z generation. Kybernetes. 2019; 48 (1):91–107. doi: 10.1108/K-09-2017-0356. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seplaki CL, Agree EM, Weiss CO, Szanton SL, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried LP. Assistive devices in context: Cross-sectional association between challenges in the home environment and use of assistive devices for mobility. The Gerontologist. 2014; 54 (4):651–660. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt030. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Simbulan N. COVID-19 and its impact on higher education in the Philippines. Higher Education in Southeast Asia and beyond. 2020; 8 :15–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Singh K, Srivastav S, Bhardwaj A, Dixit A, Misra S. Medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single institution experience. Indian Pediatrics. 2020; 57 (7):678–679. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-1899-2. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Singh V, Thurman A. How many ways can we define online learning? A systematic literature review of definitions of online learning (1988–2018) American Journal of Distance Education. 2019; 33 (4):289–306. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2019.1663082. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spector P. Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: A comment on the use of a controversial method. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1994; 15 (5):385–392. doi: 10.1002/job.4030150503. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Suryaman M, Cahyono Y, Muliansyah D, Bustani O, Suryani P, Fahlevi M, Munthe AP. COVID-19 pandemic and home online learning system: Does it affect the quality of pharmacy school learning? Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy. 2020; 11 :524–530. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tallent-Runnels MK, Thomas JA, Lan WY, Cooper S, Ahern TC, Shaw SM, Liu X. Teaching courses online: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research. 2006; 76 (1):93–135. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001093. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tang, T., Abuhmaid, A. M., Olaimat, M., Oudat, D. M., Aldhaeebi, M., & Bamanger, E. (2020). Efficiency of flipped classroom with online-based teaching under COVID-19. Interactive Learning Environments , 1–12.

- Usher M, Barak M. Team diversity as a predictor of innovation in team projects of face-to-face and online learners. Computers & Education. 2020; 144 :103702. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103702. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Varea, V., & González-Calvo, G. (2020). Touchless classes and absent bodies: Teaching physical education in times of Covid-19. Sport, Education and Society , 1–15.

- Wallace RM. Online learning in higher education: A review of research on interactions among teachers and students. Education, Communication & Information. 2003; 3 (2):241–280. doi: 10.1080/14636310303143. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization (2020). Coronavirus . https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

- Xue, E., Li, J., Li, T., & Shang, W. (2020). China’s education response to COVID-19: A perspective of policy analysis. Educational Philosophy and Theory , 1–13.

Online classes and learning in the Philippines during the Covid-19 Pandemic

- Aris E. Ignacio College of Information Technology Southville International School and Colleges Las Piñas City 1740, Philippines

The COVID-19 pandemic brought great disruption to all aspects of life specifically on how classes were conducted both in an offline and online modes. The sudden shift to purely online method of teaching and learning was a result of the lockdowns that were imposed by the Philippine government. While some institutions have dealt with the situation by shutting down operations, others continued to deliver instructions and lessons using the Internet and different applications that support online learning. The continuation of classes online had caused several issues from students and teachers ranging from lack of technology to mental health matters. Finally, recommendations were asserted to mitigate the presented concerns and improve the delivery of the necessary quality education to the intended learners.

Austria, I., Ignacio, A., Mirandilla-Santos, M.G. & Yu, W. (2020). Learning from Home: How Philippine Schools Can Respond to the COVID-19 Outbreak. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/notes/381262523025716/

Bernardo, J. (2020). DepEd eyes blending online, classroom learning for next school year. Retrieved from https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/04/21/20/deped-eyes-blending-online-classroom-learning-for-next-school-year

Change.org. (2020). Revise the academic calendar and suspend online classes throughout COVID-19 crisis. Retrieved from https://www.change.org/p/de-la-salle-dasmarińas-revise-the-academic-calendar-suspend-the-online-classes-throughout-covid-19-crisis

Commission of Higher Education. (2020). Chairman’s statement. Retrieved from https://ched.gov.ph/blog/2020/03/17/chairmans-statement/

GMA News. (2020). Student climbs mountain in search of signal to send school requirements. Retrieved from https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/hashtag/content/736143/student-climbs-mountain-in-search-of-signal-to-send-school-requirements/story/

Guno, N. (2020). Students from ‘Big 4’ universities seek online class suspension from CHED. Retrieved from https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1248397/students-from-big-4-universities-seek-online-class-suspension-from-ched

Ignacio, A. (2020). Personal observations and realizations on online classes and learning during COVID-19 outbreak in the Philippines. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/personal-observations-realizations-online-classes-learning-ignacio/

Moreno, J.M., & Gortazar, L. (2020). Schools’ readiness for digital elearning in the eyes of principals. An analysis from PISA 2018 and its implications for the COVID-19 (coronavirus) crisis responses. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/education/schools-readiness-digital-learning-eyes-principals-analysis-pisa-2018-and-its

OECD. (2020). Bridging the Digital Divide. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/site/schoolingfortomorrowknowledgebase/themes/ict/bridgingthedigitaldivide.htm

Presidential Communications Operations Office. (2020). Gov’t imposes community quarantine in Metro Manila to contain coronavirus. Retrieved from https://pcoo.gov.ph/news_releases/govt-imposes-community-quarantine-in-metro-manila-to-contain-coronavirus/

Punzalan, J. (2020). Education in the time of coronavirus: DepEd eyes lessons via TV, radio next school year. Retrieved from https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/04/20/20/education-in-the-time-of-coronavirus-deped-eyes-lessons-via-tv-radio-next-school-year

Roberts, E. (2019). Digital Divide. Retrieved from https://cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/cs181/projects/digital-divide/start.html

The World Bank. (2020). How countries are using edtech (including online learning, radio, television, texting) to support access to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/edutech/brief/how-countries-are-using-edtech-to-support-remote-learning-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

UNESCO. (2019). COVID-19 educational disruption and response. Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

UNESCO. (2019). National learning platforms and tools. Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/nationalresponses

University of the Philippines Open University. (2017). Massive open distance e-learning (MODeL). Retrieved from https://model.upou.edu.ph/

Yu, W. (2020). Online learning in the time of COVID19: A Computer Science educator’s point of view. Retrieved from https://arete.ateneo.edu/connect/online-learning-in-the-time-of-covid19-a-computer-science-educators-point-of-view

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2021 Aris E. Ignacio

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

In submitting the manuscript to the International Journal on Integrated Education (IJIE) , the authors certify that:

- They are authorized by their co-authors to enter into these arrangements.

- The work described has not been formally published before, except in the form of an abstract or as part of a published lecture, review, thesis, or overlay journal.

- That it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere,

- The publication has been approved by the author(s) and by responsible authorities – tacitly or explicitly – of the institutes where the work has been carried out.

- They secure the right to reproduce any material that has already been published or copyrighted elsewhere.

- They agree to the following license and copyright agreement.

License and Copyright Agreement

Authors who publish with International Journal on Integrated Education (IJIE) agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the International Journal on Integrated Education (IJIE) right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0) that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors can enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the International Journal on Integrated Education (IJIE) published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or edit it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) before and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work.

International Journal on Integrated Education

Published by: Research Parks Publishing Disclaimer: Articles published by the International Journal of Human Computing Studies have been peer-reviewed before publication. Read our Plagiarism Policy and use of this site signifies your agreement to the Terms of Use Phone: -

E-mail: [email protected]

1.png)

- Title & authors

Ignacio, Aris E. "Online Classes and Learning in the Philippines During the Covid-19 Pandemic." International Journal on Integrated Education , vol. 4, no. 3, 2021, pp. 1-6, doi: 10.31149/ijie.v4i3.1301 .

Download citation file:

The COVID-19 pandemic brought great disruption to all aspects of life specifically on how classes were conducted both in an offline and online modes. The sudden shift to purely online method of teaching and learning was a result of the lockdowns that were imposed by the Philippine government. While some institutions have dealt with the situation by shutting down operations, others continued to deliver instructions and lessons using the Internet and different applications that support online learning. The continuation of classes online had caused several issues from students and teachers ranging from lack of technology to mental health matters. Finally, recommendations were asserted to mitigate the presented concerns and improve the delivery of the necessary quality education to the intended learners.

Table of contents

Online classes and learning in the Philippines during the Covid-19 Pandemic

Chat with paper, a structural equation model predicting adults’ online learning self-efficacy, how important is the tuition fee during the covid-19 pandemic in a developing country evaluation of filipinos’ preferences on public university attributes using conjoint analysis, student perceptions of online biology learning during the covid-19 pandemic, journal pre-proof is tuition fee during the covid-19 pandemic in a developing country evaluation of filipinos’ preferences on public university attributes using conjoint analysis, ruralsync: providing digital content to remote communities in the philippines through opportunistic spectrum access, the chairman's statement, related papers (5), online learning during lockdown period for covid-19 in india, online learning as a catalyst for self-directed learning in universities during the covid-19 pandemic, integration of knowledge through online classes in the learning enhancement of students, right here, right now, online: using synchronous tools to teach business subjects to students learning in a second language, online education: a change or an alternative, trending questions (3).

Online learning in the Philippines during the Covid-19 pandemic involved a sudden shift to purely online teaching due to lockdowns, causing challenges like technology gaps and mental health issues among students and teachers.

The shift to online teaching during the pandemic in the Philippines caused disruptions and challenges for students and teachers, impacting class dynamics and learning outcomes.

- Mental health issues due to lack of social interaction. - Increased stress and anxiety from disrupted learning routines.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Online classes and learning in the Philippines during the Covid-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic brought great disruption to all aspects of life specifically on how classes were conducted both in an offline and online modes. The sudden shift to purely online method of teaching and learning was a result of the lockdowns that were imposed by the Philippine government. While some institutions have dealt with the situation by shutting down operations, others continued to deliver instructions and lessons using the Internet and different applications that support online learning. The continuation of classes online had caused several issues from students and teachers ranging from lack of technology to mental health matters. Finally, recommendations were asserted to mitigate the presented concerns and improve the delivery of the necessary quality education to the intended learners.

Related Papers

RD Deo , Abraham Deogracias

Knowing that education has been inaccessible and ineffective to some students in the Philippines, it is crucial to know the efficacy and success of the new learning setup during this time of the pandemic to assess if these new modalities are beneficial to the students or not. This paper reviewed and studied the various perceptions and lived experiences of selected students in a private university in Manila regarding online classes amidst the pandemic. Using a phenomenological approach, the researchers gathered data by interviewing 15 students who are attending online classes. Findings and results were drawn on the themes created by the researchers. It can be seen that majority of the students find online classes ineffective and only cater the privileged. Furthermore, lessons and discussions are difficult to digest using the current mode of learning. These findings signify a need to improve the mode of learning in order to provide a quality and effective education to students despite the current crisis faced by the country. Keywords: distance learning, online learning, online classes

Walailak Journal of Social Science

Asia Social Issues

Understanding students' experiences towards online learning can help in devising innovative pedagogical approaches and creating effective online learning spaces. This study aimed to solicit the perception of 80 undergraduate students in one of the leading private institutions in the Philippines towards the compulsory shift from a blended to fully online learning modality amidst the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The study used a descriptive research design involving online surveys which contained Likert scale items and open-ended questions assessing one's capacity for and the challenges to online learning, as well as the proposed recommendations for enhancing the overall online class experience. Descriptive statistics was used to group data across different subsets. Likewise, a content analysis of qualitative variables of the actual experiences of online classes using the school's learning management system was prepared. Results indicate four self-perceived challenges in online learning: technological and infrastructural difficulties, individual readiness, instructional struggles, and domestic barriers. The study recommends re-evaluation and modification of current online learning guidelines to address the aforesaid challenges and build a genuinely resilient model for technology-driven and care-centered education based on student recommendations and challenges experienced.

Universal Journal of Educational Research

Horizon Research Publishing(HRPUB) Kevin Nelson

In light of the learning continuity challenges experienced by educational institutions in the Philippines amidst the onset of the Covid-19 health crisis, the research serves to assess the conduct of emergency response online classes in a Philippine city schools division. It utilized a researcher-made instrument which assessed the profile of the respondents; their level of competence and confidence in conducting and supervising online classes; the level of preparedness of the schools; the levels of difficulty in lesson delivery and instructional supervision; and perceived advantages, disadvantages, and suggestions for improvement of online classes. Through purposive sampling, the respondents comprised 91 teachers and 24 instructional supervisors from 18 schools. Results of the study revealed that teachers and instructional supervisors needed experience and training to be able to efficiently and effectively perform their tasks in online classes; and that there were students and teachers who were not able to regularly participate in online classes due to lack of resources. Respondents also said that online classes were flexible in terms of schedule and choice of strategies, able to ensure learning continuity, were convenient, and efficient in terms of saving time, money, and effort. However, they also said that online classes had decreased participation rate, were ineffective, and had limited interaction and socialization. Conduct of training/orientation and regular practice on online classes, and ensuring needed infrastructure and resources are in place and available, respectively; as well as further research on the topic were suggested.

Education and Information Technologies

Leo del Rosario

Jurnal Prima Edukasia

rimba hamid

This study aims to obtain an in-depth overview of (1) the distribution of students at the Department of PGSD FKIP UHO based on domicile in implementing online learning during the Covid-19 period; (2) infrastructure support for the effectiveness of online learning in the Covid-19 period; and (3) students' perceptions about online learning conducted by lecturers of the Department of PGSD FKIP UHO during Covid-19. This research was conducted in May 2020, which was included in the descriptive study, by conducting a survey of students at the Department of PGSD FKIP UHO, which was spread across all districts/cities in Southeast Sulawesi and other regions. Data collection techniques using open and closed questionnaires, with the research subjects of the class of 2017, 2018 and 2019 students who filled 316 questionnaires online from the link sent. Data obtained from students in the form of qualitative and quantitative raw data collected online and converted in Excel format. The data was...

Arun Antonyraj

The Corona virus (Covid-19) pandemic out broken at the late 2019 was reported as a cluster of cases in December at Wuhan, China by The World Health Organization. The pandemic has been lasting about a year claimed more than 55 million cases and 1.5 million of death globally. This has brought into drastic changes in the normal lifestyle of people worldwide, especially into the routine of education field creating many changes into their policies and practices. The Pandemic has disrupted the cl assroom education system and paved a new normal way to online education system. The Information Communication Technologies have provided a rescue hand to bring back the student and teacher communication through online classes to persist the education. The study involves in analyzing the new normal practices at education sector in providing their classes online and the precautionary measures in enhancing the effectiveness of online classes.

Kimkong Heng

Afraseyab khattak

Afraseyab Khattak , sayyed Shah