Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

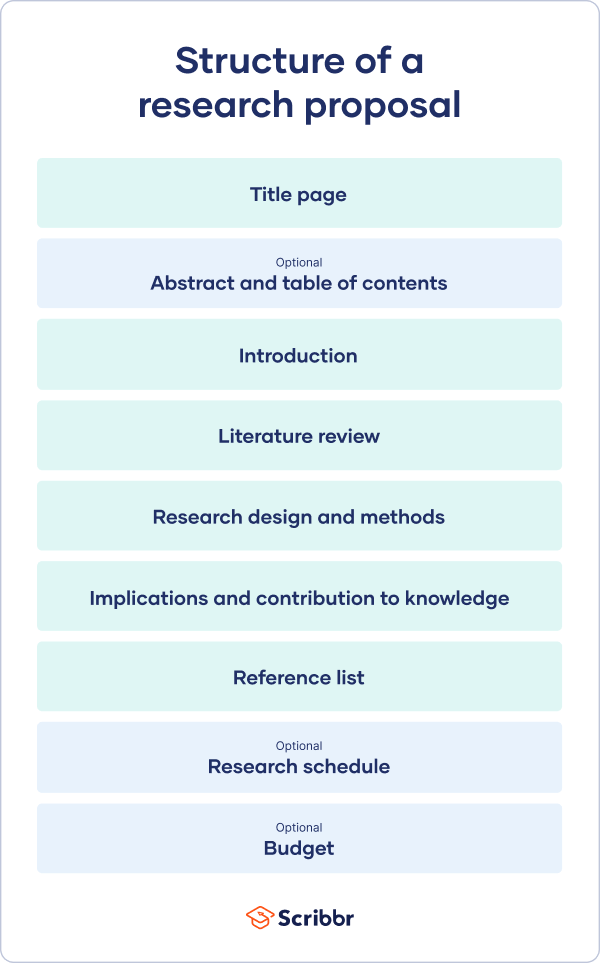

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved March 28, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Manuscript Preparation

What is the Background of a Study and How Should it be Written?

- 3 minute read

- 837.1K views

Table of Contents

The background of a study is one of the most important components of a research paper. The quality of the background determines whether the reader will be interested in the rest of the study. Thus, to ensure that the audience is invested in reading the entire research paper, it is important to write an appealing and effective background. So, what constitutes the background of a study, and how must it be written?

What is the background of a study?

The background of a study is the first section of the paper and establishes the context underlying the research. It contains the rationale, the key problem statement, and a brief overview of research questions that are addressed in the rest of the paper. The background forms the crux of the study because it introduces an unaware audience to the research and its importance in a clear and logical manner. At times, the background may even explore whether the study builds on or refutes findings from previous studies. Any relevant information that the readers need to know before delving into the paper should be made available to them in the background.

How is a background different from the introduction?

The introduction of your research paper is presented before the background. Let’s find out what factors differentiate the background from the introduction.

- The introduction only contains preliminary data about the research topic and does not state the purpose of the study. On the contrary, the background clarifies the importance of the study in detail.

- The introduction provides an overview of the research topic from a broader perspective, while the background provides a detailed understanding of the topic.

- The introduction should end with the mention of the research questions, aims, and objectives of the study. In contrast, the background follows no such format and only provides essential context to the study.

How should one write the background of a research paper?

The length and detail presented in the background varies for different research papers, depending on the complexity and novelty of the research topic. At times, a simple background suffices, even if the study is complex. Before writing and adding details in the background, take a note of these additional points:

- Start with a strong beginning: Begin the background by defining the research topic and then identify the target audience.

- Cover key components: Explain all theories, concepts, terms, and ideas that may feel unfamiliar to the target audience thoroughly.

- Take note of important prerequisites: Go through the relevant literature in detail. Take notes while reading and cite the sources.

- Maintain a balance: Make sure that the background is focused on important details, but also appeals to a broader audience.

- Include historical data: Current issues largely originate from historical events or findings. If the research borrows information from a historical context, add relevant data in the background.

- Explain novelty: If the research study or methodology is unique or novel, provide an explanation that helps to understand the research better.

- Increase engagement: To make the background engaging, build a story around the central theme of the research

Avoid these mistakes while writing the background:

- Ambiguity: Don’t be ambiguous. While writing, assume that the reader does not understand any intricate detail about your research.

- Unrelated themes: Steer clear from topics that are not related to the key aspects of your research topic.

- Poor organization: Do not place information without a structure. Make sure that the background reads in a chronological manner and organize the sub-sections so that it flows well.

Writing the background for a research paper should not be a daunting task. But directions to go about it can always help. At Elsevier Author Services we provide essential insights on how to write a high quality, appealing, and logically structured paper for publication, beginning with a robust background. For further queries, contact our experts now!

How to Use Tables and Figures effectively in Research Papers

- Research Process

The Top 5 Qualities of Every Good Researcher

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write an Effective Background of the Study: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

The background of the study in a research paper offers a clear context, highlighting why the research is essential and the problem it aims to address.

As a researcher, this foundational section is essential for you to chart the course of your study, Moreover, it allows readers to understand the importance and path of your research.

Whether in academic communities or to the general public, a well-articulated background aids in communicating the essence of the research effectively.

While it may seem straightforward, crafting an effective background requires a blend of clarity, precision, and relevance. Therefore, this article aims to be your guide, offering insights into:

- Understanding the concept of the background of the study.

- Learning how to craft a compelling background effectively.

- Identifying and sidestepping common pitfalls in writing the background.

- Exploring practical examples that bring the theory to life.

- Enhancing both your writing and reading of academic papers.

Keeping these compelling insights in mind, let's delve deeper into the details of the empirical background of the study, exploring its definition, distinctions, and the art of writing it effectively.

What is the background of the study?

The background of the study is placed at the beginning of a research paper. It provides the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being explored.

It offers readers a snapshot of the existing knowledge on the topic and the reasons that spurred your current research.

When crafting the background of your study, consider the following questions.

- What's the context of your research?

- Which previous research will you refer to?

- Are there any knowledge gaps in the existing relevant literature?

- How will you justify the need for your current research?

- Have you concisely presented the research question or problem?

In a typical research paper structure, after presenting the background, the introduction section follows. The introduction delves deeper into the specific objectives of the research and often outlines the structure or main points that the paper will cover.

Together, they create a cohesive starting point, ensuring readers are well-equipped to understand the subsequent sections of the research paper.

While the background of the study and the introduction section of the research manuscript may seem similar and sometimes even overlap, each serves a unique purpose in the research narrative.

Difference between background and introduction

A well-written background of the study and introduction are preliminary sections of a research paper and serve distinct purposes.

Here’s a detailed tabular comparison between the two of them.

What is the relevance of the background of the study?

It is necessary for you to provide your readers with the background of your research. Without this, readers may grapple with questions such as: Why was this specific research topic chosen? What led to this decision? Why is this study relevant? Is it worth their time?

Such uncertainties can deter them from fully engaging with your study, leading to the rejection of your research paper. Additionally, this can diminish its impact in the academic community, and reduce its potential for real-world application or policy influence .

To address these concerns and offer clarity, the background section plays a pivotal role in research papers.

The background of the study in research is important as it:

- Provides context: It offers readers a clear picture of the existing knowledge, helping them understand where the current research fits in.

- Highlights relevance: By detailing the reasons for the research, it underscores the study's significance and its potential impact.

- Guides the narrative: The background shapes the narrative flow of the paper, ensuring a logical progression from what's known to what the research aims to uncover.

- Enhances engagement: A well-crafted background piques the reader's interest, encouraging them to delve deeper into the research paper.

- Aids in comprehension: By setting the scenario, it aids readers in better grasping the research objectives, methodologies, and findings.

How to write the background of the study in a research paper?

The journey of presenting a compelling argument begins with the background study. This section holds the power to either captivate or lose the reader's interest.

An effectively written background not only provides context but also sets the tone for the entire research paper. It's the bridge that connects a broad topic to a specific research question, guiding readers through the logic behind the study.

But how does one craft a background of the study that resonates, informs, and engages?

Here, we’ll discuss how to write an impactful background study, ensuring your research stands out and captures the attention it deserves.

Identify the research problem

The first step is to start pinpointing the specific issue or gap you're addressing. This should be a significant and relevant problem in your field.

A well-defined problem is specific, relevant, and significant to your field. It should resonate with both experts and readers.

Here’s more on how to write an effective research problem .

Provide context

Here, you need to provide a broader perspective, illustrating how your research aligns with or contributes to the overarching context or the wider field of study. A comprehensive context is grounded in facts, offers multiple perspectives, and is relatable.

In addition to stating facts, you should weave a story that connects key concepts from the past, present, and potential future research. For instance, consider the following approach.

- Offer a brief history of the topic, highlighting major milestones or turning points that have shaped the current landscape.

- Discuss contemporary developments or current trends that provide relevant information to your research problem. This could include technological advancements, policy changes, or shifts in societal attitudes.

- Highlight the views of different stakeholders. For a topic like sustainable agriculture, this could mean discussing the perspectives of farmers, environmentalists, policymakers, and consumers.

- If relevant, compare and contrast global trends with local conditions and circumstances. This can offer readers a more holistic understanding of the topic.

Literature review

For this step, you’ll deep dive into the existing literature on the same topic. It's where you explore what scholars, researchers, and experts have already discovered or discussed about your topic.

Conducting a thorough literature review isn't just a recap of past works. To elevate its efficacy, it's essential to analyze the methods, outcomes, and intricacies of prior research work, demonstrating a thorough engagement with the existing body of knowledge.

- Instead of merely listing past research study, delve into their methodologies, findings, and limitations. Highlight groundbreaking studies and those that had contrasting results.

- Try to identify patterns. Look for recurring themes or trends in the literature. Are there common conclusions or contentious points?

- The next step would be to connect the dots. Show how different pieces of research relate to each other. This can help in understanding the evolution of thought on the topic.

By showcasing what's already known, you can better highlight the background of the study in research.

Highlight the research gap

This step involves identifying the unexplored areas or unanswered questions in the existing literature. Your research seeks to address these gaps, providing new insights or answers.

A clear research gap shows you've thoroughly engaged with existing literature and found an area that needs further exploration.

How can you efficiently highlight the research gap?

- Find the overlooked areas. Point out topics or angles that haven't been adequately addressed.

- Highlight questions that have emerged due to recent developments or changing circumstances.

- Identify areas where insights from other fields might be beneficial but haven't been explored yet.

State your objectives

Here, it’s all about laying out your game plan — What do you hope to achieve with your research? You need to mention a clear objective that’s specific, actionable, and directly tied to the research gap.

How to state your objectives?

- List the primary questions guiding your research.

- If applicable, state any hypotheses or predictions you aim to test.

- Specify what you hope to achieve, whether it's new insights, solutions, or methodologies.

Discuss the significance

This step describes your 'why'. Why is your research important? What broader implications does it have?

The significance of “why” should be both theoretical (adding to the existing literature) and practical (having real-world implications).

How do we effectively discuss the significance?

- Discuss how your research adds to the existing body of knowledge.

- Highlight how your findings could be applied in real-world scenarios, from policy changes to on-ground practices.

- Point out how your research could pave the way for further studies or open up new areas of exploration.

Summarize your points

A concise summary acts as a bridge, smoothly transitioning readers from the background to the main body of the paper. This step is a brief recap, ensuring that readers have grasped the foundational concepts.

How to summarize your study?

- Revisit the key points discussed, from the research problem to its significance.

- Prepare the reader for the subsequent sections, ensuring they understand the research's direction.

Include examples for better understanding

Research and come up with real-world or hypothetical examples to clarify complex concepts or to illustrate the practical applications of your research. Relevant examples make abstract ideas tangible, aiding comprehension.

How to include an effective example of the background of the study?

- Use past events or scenarios to explain concepts.

- Craft potential scenarios to demonstrate the implications of your findings.

- Use comparisons to simplify complex ideas, making them more relatable.

Crafting a compelling background of the study in research is about striking the right balance between providing essential context, showcasing your comprehensive understanding of the existing literature, and highlighting the unique value of your research .

While writing the background of the study, keep your readers at the forefront of your mind. Every piece of information, every example, and every objective should be geared toward helping them understand and appreciate your research.

How to avoid mistakes in the background of the study in research?

To write a well-crafted background of the study, you should be aware of the following potential research pitfalls .

- Stay away from ambiguity. Always assume that your reader might not be familiar with intricate details about your topic.

- Avoid discussing unrelated themes. Stick to what's directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure your background is well-organized. Information should flow logically, making it easy for readers to follow.

- While it's vital to provide context, avoid overwhelming the reader with excessive details that might not be directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure you've covered the most significant and relevant studies i` n your field. Overlooking key pieces of literature can make your background seem incomplete.

- Aim for a balanced presentation of facts, and avoid showing overt bias or presenting only one side of an argument.

- While academic paper often involves specialized terms, ensure they're adequately explained or use simpler alternatives when possible.

- Every claim or piece of information taken from existing literature should be appropriately cited. Failing to do so can lead to issues of plagiarism.

- Avoid making the background too lengthy. While thoroughness is appreciated, it should not come at the expense of losing the reader's interest. Maybe prefer to keep it to one-two paragraphs long.

- Especially in rapidly evolving fields, it's crucial to ensure that your literature review section is up-to-date and includes the latest research.

Example of an effective background of the study

Let's consider a topic: "The Impact of Online Learning on Student Performance." The ideal background of the study section for this topic would be as follows.

In the last decade, the rise of the internet has revolutionized many sectors, including education. Online learning platforms, once a supplementary educational tool, have now become a primary mode of instruction for many institutions worldwide. With the recent global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rapid shift from traditional classroom learning to online modes, making it imperative to understand its effects on student performance.

Previous studies have explored various facets of online learning, from its accessibility to its flexibility. However, there is a growing need to assess its direct impact on student outcomes. While some educators advocate for its benefits, citing the convenience and vast resources available, others express concerns about potential drawbacks, such as reduced student engagement and the challenges of self-discipline.

This research aims to delve deeper into this debate, evaluating the true impact of online learning on student performance.

Why is this example considered as an effective background section of a research paper?

This background section example effectively sets the context by highlighting the rise of online learning and its increased relevance due to recent global events. It references prior research on the topic, indicating a foundation built on existing knowledge.

By presenting both the potential advantages and concerns of online learning, it establishes a balanced view, leading to the clear purpose of the study: to evaluate the true impact of online learning on student performance.

As we've explored, writing an effective background of the study in research requires clarity, precision, and a keen understanding of both the broader landscape and the specific details of your topic.

From identifying the research problem, providing context, reviewing existing literature to highlighting research gaps and stating objectives, each step is pivotal in shaping the narrative of your research. And while there are best practices to follow, it's equally crucial to be aware of the pitfalls to avoid.

Remember, writing or refining the background of your study is essential to engage your readers, familiarize them with the research context, and set the ground for the insights your research project will unveil.

Drawing from all the important details, insights and guidance shared, you're now in a strong position to craft a background of the study that not only informs but also engages and resonates with your readers.

Now that you've a clear understanding of what the background of the study aims to achieve, the natural progression is to delve into the next crucial component — write an effective introduction section of a research paper. Read here .

Frequently Asked Questions

The background of the study should include a clear context for the research, references to relevant previous studies, identification of knowledge gaps, justification for the current research, a concise overview of the research problem or question, and an indication of the study's significance or potential impact.

The background of the study is written to provide readers with a clear understanding of the context, significance, and rationale behind the research. It offers a snapshot of existing knowledge on the topic, highlights the relevance of the study, and sets the stage for the research questions and objectives. It ensures that readers can grasp the importance of the research and its place within the broader field of study.

The background of the study is a section in a research paper that provides context, circumstances, and history leading to the research problem or topic being explored. It presents existing knowledge on the topic and outlines the reasons that spurred the current research, helping readers understand the research's foundation and its significance in the broader academic landscape.

The number of paragraphs in the background of the study can vary based on the complexity of the topic and the depth of the context required. Typically, it might range from 3 to 5 paragraphs, but in more detailed or complex research papers, it could be longer. The key is to ensure that all relevant information is presented clearly and concisely, without unnecessary repetition.

You might also like

Cybersecurity in Higher Education: Safeguarding Students and Faculty Data

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Beyond Google Scholar: Why SciSpace is the best alternative

How to write your research proposal

A key part of your application is your research proposal. Whether you are applying for a self-funded or studentship you should follow the guidance below.

If you are looking specifically for advice on writing your PhD by published work research proposal, read our guide .

You are encouraged to contact us to discuss the availability of supervision in your area of research before you make a formal application, by visiting our areas of research .

What is your research proposal used for and why is it important?

- It is used to establish whether there is expertise to support your proposed area of research

- It forms part of the assessment of your application

- The research proposal you submit as part of your application is just the starting point, as your ideas evolve your proposed research is likely to change

How long should my research proposal be?

It should be 2,000–3,500 words (4-7 pages) long.

What should be included in my research proposal?

Your proposal should include the following:

- your title should give a clear indication of your proposed research approach or key question

2. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

You should include:

- the background and issues of your proposed research

- identify your discipline

- a short literature review

- a summary of key debates and developments in the field

3. RESEARCH QUESTION(S)

You should formulate these clearly, giving an explanation as to what problems and issues are to be explored and why they are worth exploring

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

You should provide an outline of:

- the theoretical resources to be drawn on

- the research approach (theoretical framework)

- the research methods appropriate for the proposed research

- a discussion of advantages as well as limits of particular approaches and methods

5. PLAN OF WORK & TIME SCHEDULE

You should include an outline of the various stages and corresponding time lines for developing and implementing the research, including writing up your thesis.

For full-time study your research should be completed within three years, with writing up completed in the fourth year of registration.

For part-time study your research should be completed within six years, with writing up completed by the eighth year.

6. BIBLIOGRAPHY

- a list of references to key articles and texts discussed within your research proposal

- a selection of sources appropriate to the proposed research

Related pages

Fees and funding.

How much will it cost to study a research degree?

Research degrees

Find out if you can apply for a Research Degree at the University of Westminster.

Research degree by distance learning

Find out about Research Degree distance learning options at the University of Westminster.

We use cookies to ensure the best experience on our website.

By accepting you agree to cookies being stored on your device.

Some of these cookies are essential to the running of the site, while others help us to improve your experience.

Functional cookies enable core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility.

Analytics cookies help us improve our website based on user needs by collecting information, which does not directly identify anyone.

Marketing cookies send information on your visit to third parties so that they can make their advertising more relevant to you when you visit other websites.

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Training and Development

- Beginner Guides

Blog Education

How to Write a Research Proposal: A Step-by-Step

By Danesh Ramuthi , Nov 29, 2023

A research proposal is a structured outline for a planned study on a specific topic. It serves as a roadmap, guiding researchers through the process of converting their research idea into a feasible project.

The aim of a research proposal is multifold: it articulates the research problem, establishes a theoretical framework, outlines the research methodology and highlights the potential significance of the study. Importantly, it’s a critical tool for scholars seeking grant funding or approval for their research projects.

Crafting a good research proposal requires not only understanding your research topic and methodological approaches but also the ability to present your ideas clearly and persuasively. Explore Venngage’s Proposal Maker and Research Proposals Templates to begin your journey in writing a compelling research proposal.

What to include in a research proposal?

In a research proposal, include a clear statement of your research question or problem, along with an explanation of its significance. This should be followed by a literature review that situates your proposed study within the context of existing research.

Your proposal should also outline the research methodology, detailing how you plan to conduct your study, including data collection and analysis methods.

Additionally, include a theoretical framework that guides your research approach, a timeline or research schedule, and a budget if applicable. It’s important to also address the anticipated outcomes and potential implications of your study. A well-structured research proposal will clearly communicate your research objectives, methods and significance to the readers.

How to format a research proposal?

Formatting a research proposal involves adhering to a structured outline to ensure clarity and coherence. While specific requirements may vary, a standard research proposal typically includes the following elements:

- Title Page: Must include the title of your research proposal, your name and affiliations. The title should be concise and descriptive of your proposed research.

- Abstract: A brief summary of your proposal, usually not exceeding 250 words. It should highlight the research question, methodology and the potential impact of the study.

- Introduction: Introduces your research question or problem, explains its significance, and states the objectives of your study.

- Literature review: Here, you contextualize your research within existing scholarship, demonstrating your knowledge of the field and how your research will contribute to it.

- Methodology: Outline your research methods, including how you will collect and analyze data. This section should be detailed enough to show the feasibility and thoughtfulness of your approach.

- Timeline: Provide an estimated schedule for your research, breaking down the process into stages with a realistic timeline for each.

- Budget (if applicable): If your research requires funding, include a detailed budget outlining expected cost.

- References/Bibliography: List all sources referenced in your proposal in a consistent citation style.

How to write a research proposal in 11 steps?

Writing a research proposal in structured steps ensures a comprehensive and coherent presentation of your research project. Let’s look at the explanation for each of the steps here:

Step 1: Title and Abstract Step 2: Introduction Step 3: Research objectives Step 4: Literature review Step 5: Methodology Step 6: Timeline Step 7: Resources Step 8: Ethical considerations Step 9: Expected outcomes and significance Step 10: References Step 11: Appendices

Step 1: title and abstract.

Select a concise, descriptive title and write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology and expected outcomes. The abstract should include your research question, the objectives you aim to achieve, the methodology you plan to employ and the anticipated outcomes.

Step 2: Introduction

In this section, introduce the topic of your research, emphasizing its significance and relevance to the field. Articulate the research problem or question in clear terms and provide background context, which should include an overview of previous research in the field.

Step 3: Research objectives

Here, you’ll need to outline specific, clear and achievable objectives that align with your research problem. These objectives should be well-defined, focused and measurable, serving as the guiding pillars for your study. They help in establishing what you intend to accomplish through your research and provide a clear direction for your investigation.

Step 4: Literature review

In this part, conduct a thorough review of existing literature related to your research topic. This involves a detailed summary of key findings and major contributions from previous research. Identify existing gaps in the literature and articulate how your research aims to fill these gaps. The literature review not only shows your grasp of the subject matter but also how your research will contribute new insights or perspectives to the field.

Step 5: Methodology

Describe the design of your research and the methodologies you will employ. This should include detailed information on data collection methods, instruments to be used and analysis techniques. Justify the appropriateness of these methods for your research.

Step 6: Timeline

Construct a detailed timeline that maps out the major milestones and activities of your research project. Break the entire research process into smaller, manageable tasks and assign realistic time frames to each. This timeline should cover everything from the initial research phase to the final submission, including periods for data collection, analysis and report writing.

It helps in ensuring your project stays on track and demonstrates to reviewers that you have a well-thought-out plan for completing your research efficiently.

Step 7: Resources

Identify all the resources that will be required for your research, such as specific databases, laboratory equipment, software or funding. Provide details on how these resources will be accessed or acquired.

If your research requires funding, explain how it will be utilized effectively to support various aspects of the project.

Step 8: Ethical considerations

Address any ethical issues that may arise during your research. This is particularly important for research involving human subjects. Describe the measures you will take to ensure ethical standards are maintained, such as obtaining informed consent, ensuring participant privacy, and adhering to data protection regulations.

Here, in this section you should reassure reviewers that you are committed to conducting your research responsibly and ethically.

Step 9: Expected outcomes and significance

Articulate the expected outcomes or results of your research. Explain the potential impact and significance of these outcomes, whether in advancing academic knowledge, influencing policy or addressing specific societal or practical issues.

Step 10: References

Compile a comprehensive list of all the references cited in your proposal. Adhere to a consistent citation style (like APA or MLA) throughout your document. The reference section not only gives credit to the original authors of your sourced information but also strengthens the credibility of your proposal.

Step 11: Appendices

Include additional supporting materials that are pertinent to your research proposal. This can be survey questionnaires, interview guides, detailed data analysis plans or any supplementary information that supports the main text.

Appendices provide further depth to your proposal, showcasing the thoroughness of your preparation.

Research proposal FAQs

1. how long should a research proposal be.

The length of a research proposal can vary depending on the requirements of the academic institution, funding body or specific guidelines provided. Generally, research proposals range from 500 to 1500 words or about one to a few pages long. It’s important to provide enough detail to clearly convey your research idea, objectives and methodology, while being concise. Always check

2. Why is the research plan pivotal to a research project?

The research plan is pivotal to a research project because it acts as a blueprint, guiding every phase of the study. It outlines the objectives, methodology, timeline and expected outcomes, providing a structured approach and ensuring that the research is systematically conducted.

A well-crafted plan helps in identifying potential challenges, allocating resources efficiently and maintaining focus on the research goals. It is also essential for communicating the project’s feasibility and importance to stakeholders, such as funding bodies or academic supervisors.

Mastering how to write a research proposal is an essential skill for any scholar, whether in social and behavioral sciences, academic writing or any field requiring scholarly research. From this article, you have learned key components, from the literature review to the research design, helping you develop a persuasive and well-structured proposal.

Remember, a good research proposal not only highlights your proposed research and methodology but also demonstrates its relevance and potential impact.

For additional support, consider utilizing Venngage’s Proposal Maker and Research Proposals Templates , valuable tools in crafting a compelling proposal that stands out.

Whether it’s for grant funding, a research paper or a dissertation proposal, these resources can assist in transforming your research idea into a successful submission.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.