To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, effective police investigative practices: an evidence-assessment of the research.

Policing: An International Journal

ISSN : 1363-951X

Article publication date: 23 June 2021

Issue publication date: 31 August 2021

Detective work is a mainstay of modern law enforcement, but its effectiveness has been much less evaluated than patrol work. To explore what is known about effective investigative practices and to identify evidence gaps, the authors assess the current state of empirical research on investigations.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors assess the empirical research about the effectiveness of criminal investigations and detective work in resolving cases and improving clearance rates.

The authors’ analysis of the literature produced 80 studies that focus on seven categories of investigations research, which include the impact that case and situational factors, demographic and neighborhood dynamics, organizational policies and practices, investigative effort, technology, patrol officers and community members have on case resolution. The authors’ assessment shows that evaluation research examining the effectiveness of various investigative activities is rare. However, the broader empirical literature indicates that a combination of organizational policies, investigative effort and certain technologies can be promising in improving investigative outcomes even in cases deemed less solvable.

Research limitations/implications

From an evidence-based perspective, this review emphasizes the need for greater transparency, evaluation and accountability of investigative activities given the resources and importance afforded to criminal investigations.

Originality/value

This review is currently the most up-to-date review of the state of the research on what is known about effective investigative practices.

- Investigations

- Evidence-based policing

- Effectiveness

Acknowledgements

This evidence-assessment was funded by a grant from Arnold Ventures.

Prince, H. , Lum, C. and Koper, C.S. (2021), "Effective police investigative practices: an evidence-assessment of the research", Policing: An International Journal , Vol. 44 No. 4, pp. 683-707. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-04-2021-0054

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- You are here:

- American Chemical Society

- Discover Chemistry

Recent advances in forensic science research

For immediate release, acs news service weekly presspac: april 20, 2022.

Forensic scientists collect and analyze evidence during a criminal investigation to identify victims, determine the cause of death and figure out “who done it.” Below are some recent papers published in ACS journals reporting on new advances that could help forensic scientists solve crimes. Reporters can request free access to these papers by emailing newsroom@acs.org .

“Insights into the Differential Preservation of Bone Proteomes in Inhumed and Entombed Cadavers from Italian Forensic Caseworks” Journal of Proteome Research March 22, 2022 Bone proteins can help determine how long ago a person died (post-mortem interval, PMI) and how old they were at the time of their death (age at death, AAD), but the levels of these proteins could vary with burial conditions. By comparing bone proteomes of exhumed individuals who had been entombed in mausoleums or buried in the ground, the researchers found several proteins whose levels were not affected by the burial environment, which they say could help with AAD or PMI estimation.

“Carbon Dot Powders with Cross-Linking-Based Long-Wavelength Emission for Multicolor Imaging of Latent Fingerprints” ACS Applied Nanomaterials Jan. 21, 2022 For decades, criminal investigators have recognized the importance of analyzing latent fingerprints left at crime scenes to help identify a perpetrator, but current methods to make these prints visible have limitations, including low contrast, low sensitivity and high toxicity. These researchers devised a simple way to make fluorescent carbon dot powders that can be applied to latent fingerprints, making them fluoresce under UV light with red, orange and yellow colors.

“Proteomics Offers New Clues for Forensic Investigations” ACS Central Science Oct. 18, 2021 This review article describes how forensic scientists are now turning their attention to proteins in bone, blood or other biological samples, which can sometimes answer questions that DNA can’t. For example, unlike DNA, a person’s complement of proteins (or proteome) changes over time, providing important clues about when a person died and their age at death.

“Integrating the MasSpec Pen with Sub-Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization for Rapid Chemical Analysis and Forensic Applications” Analytical Chemistry May 19, 2021 These researchers previously developed a “MasSpec Pen,” a handheld device integrated with a mass spectrometer for direct analysis and molecular profiling of biological samples. In this article, they develop a new version that can quickly and easily detect and measure compounds, including cocaine, oxycodone and explosives, which can be important in forensics investigations.

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News . ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive press releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org .

Note: ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.

Media Contact

ACS Newsroom newsroom@acs.org

Discover Chemistry —Menu

- News Releases

- ACS in the News

Accept & Close The ACS takes your privacy seriously as it relates to cookies. We use cookies to remember users, better understand ways to serve them, improve our value proposition, and optimize their experience. Learn more about managing your cookies at Cookies Policy .

1155 Sixteenth Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036, USA | service@acs.org | 1-800-333-9511 (US and Canada) | 614-447-3776 (outside North America)

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility

Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society

Criminal Justice Resources

Articles and papers/reports, selected books and law-related material, statistics/data, organizations, other sources, 50-state surveys, historical archives/research, what is happening in criminal justice, getting help, introduction.

This guide is meant to serve as a starting place for people researching criminal justice and related criminal law issues. It focuses primarly on issues related to the United States. For more criminal law sources (particularly for 1L's), be sure to check out our guides for Criminal Law and Law and Public Policy and the Kennedy School Library's Criminal Justice guide.

Subject Guide

Indexing/abstracting resources focused on criminal justice

- Crime and Delinquency Abstracts Covers 1963-1972. National Council on Crime and Delinquency and National Clearinghouse for Mental Health Information. Previously,

- Criminal Justice Abstracts (Harvard Key Login) Criminal Justice Abstracts provides comprehensive coverage of U.S. and international criminal justice literature including scholarly journals, books, dissertations, governmental and non-governmental studies and reports, unpublished papers, magazines, newsletters and other materials. In addition to criminal justice and criminology, topics covered include criminal law and procedure, corrections and prisons, police and policing, criminal investigation, forensic sciences and investigation, history of crime, substance abuse and addiction, and probation and parole. 1968-current. more... less... Criminal Justice Abstracts provides comprehensive coverage of U.S. and international criminal justice literature including scholarly journals, books, dissertations, governmental and non-governmental studies and reports, unpublished papers, magazines, newsletters and other materials. In addition to criminal justice and criminology, topics covered include criminal law and procedure, corrections and prisons, police and policing, criminal investigation, forensic sciences and investigation, history of crime, substance abuse and addiction, and probation and parole.

- NCJRS The National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS) is a federally funded resource offering justice and substance abuse information to support research, policy, and program development worldwide. The NCJRS Abstracts Database contains summaries of the more than 185,000 criminal justice publications housed in the NCJRS Library collection. Most documents published by NCJRS sponsoring agencies since 1995 are available in full-text online. A link is included with the abstract when the full-text is available. Use the Thesaurus Term Search to search for materials in the NCJRS Abstracts Database using an NCJRS controlled vocabulary. This controlled vocabulary is used to assign relevant indexing terms to the documents in the NCJRS collection.

Finding legal articles and papers

- Index to Legal Periodicals and Books

- Index to Legal Periodicals Retrospective: 1908-1981 (Law Login Required) covers back to 1908 more... less... This retrospective database indexes over 750 legal periodicals published in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. Annual surveys of the laws of a jurisdiction, annual surveys of the federal courts, yearbooks, annual institutes, and annual reviews of the work in a given field or on a given topic will also be covered.

- More resources for finding legal articles

Multidisciplinary databases

- Academic Search Premier (Harvard Login) more... less... Academic Search Premier (ASP) is a multi-disciplinary database that includes citations and abstracts from over 4,700 scholarly publications (journals, magazines and newspapers). Full text is available for more than 3,600 of the publications and is searchable.

- JSTOR more... less... Includes all titles in the JSTOR collection, excluding recent issues. JSTOR (www.jstor.org) is a not-for-profit organization with a dual mission to create and maintain a trusted archive of important scholarly journals, and to provide access to these journals as widely as possible. Content in JSTOR spans many disciplines, primarily in the humanities and social sciences. For complete lists of titles and collections, please refer to http://www.jstor.org/about/collection.list.html.

Other social science databases related to criminal justice

- PAIS International (Harvard Login) provides access to materials about public policy, including academic journal articles, yearbooks, books, reports and pamphlets. Items indexed include works by academics, agencies, international organizations and federal, state and local governments from 1972 to the present. PAIS covers over 1,600 journals and roughly 8,000 books each year. PAIS is international in scope and contains items in many romance languages. more... less... PAIS International indexes the public and social policy literature of public administration, political science, economics, finance, international relations, law, and health care, International in scope, PAIS indexes publications in English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. The database is comprised of abstracts of thousands of journal articles, books, directories, conference proceedings, government documents and statistical yearbooks.

- More academic resources by field

- Law and Public Policy Guide

- Urban Studies Abstracts (Harvard Login) more... less... Electronic index and abstracts to the literature in the area of urban studies, including urban affairs, community development, and urban history. The backfile of this index has been digitized, providing coverage back to 1973.

Selected Journals and newsletters

- Annual Review of Criminal Procedure (Georgetown) Latest issue available in print at Law School KF9619 .G46

- Federal Sentencing Reporter also on Lexis

Congressional publications/government reports

- CRS reports

- House and Senate Hearings, Congressional Record Permanent Digital Collection, and Digital US Bills and Resolutions

- Federal Legislative History

- US Department of Justice

- PolicyFile (Harvard Login) Abstracts of and links to domestic and international public policy issue published by think tanks, university research programs, & research organizations. more... less... PolicyFile provides abstracts (more than half of the abstracts link to the full text documents) of domestic and international public policy issues. The public policy reports and studies are published by think tanks, university research programs, research organizations which include the OECD, IMF, World Bank, the Rand Corporation, and a number of federal agencies. The database search engine allows users to search by title, author, subject, organization and keyword.

- Rutgers University Don M. Gottsfredson School of Criminal Justice Gray Literature Database

Rules of Criminal Procedure

- Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure (Federal Rules of Practice & Procedure) Includes postings of proposed rule changes. From the uscourts.gov website.

- Rulemaking (Pending Rules)(US Courts)

Model Penal Code

- Criminal Law: Model Penal Code

- Model Penal Code and Commentaries (official draft and revised comments) : with text of Model penal code as adopted at the 1962 Annual Meeting of the American Law Institute at Washington, D.C., May 24, 1962.

- Model penal code : official draft and explanatory notes : complete text of Model penal code as adopted at the 1962 Annual Meeting of the American Law Institute at Washington, D.C., May 24, 1962.

- Model Penal Code (ALI Library) Includes drafts

Selected Criminal Law Treatises, Basic Texts and Practice Manuals

Below are sources related to criminal law generally or focused on federal criminal law. For a particular jurisdiction, look for secondary sources related to that particular state. For constitutional issues, see also secondary sources related to constitutional law more generally.

- United States Attorneys Manual

- Legal Division Reference Book

- United States Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual

Search and Seizure

- Search and Seizure also on Lexis

Sources for criminal justice statistics generally

- Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics Currently in transition (no longer funded by the Bureau of Justice Statistics), but still a good starting place. Data included as of 2013.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics

- FBI Uniform Crime Reports Annual report is Crime in the United States .

- National Crime Victimization Survey See also NCVS Victimization Analysis Tool and National Crime Victimization Survey Resource Guide .

- Justice Research and Statistics Association

- National Archive of Criminal Justice Data

- United States Sentencing Commission (USSC) Interactive Sourcebook

- Sunlight Criminal Justice Project Its Hall of Justice provides a searchable inventory of publically available criminal justice data sets and research.

- Arrest Data Analysis Tool underlying data from FBI's UCR (Uniform Crime Reports)

- Measures for Justice

- State Criminal Caseloads

- United States Historical Corrections Statistics - 1850-1984 from BJS abstract: "The introductory chapter contains a brief history of Federal corrections data collection efforts. Summary information on capital punishment includes data on illegal lynchings by race and offense, regional comparisons of the number of persons executed, the number under the death sentence, the number of women executed, and the number of persons removed from the death sentence other than by execution. Prison statistics cover the number in Federal, State, and juvenile facilities; the average sentence by sex, region, race, and offense; length of sentence; and type of release. Statistics also cover facility staff, inmate-staff ratio, and jail inmates. Probation and parole statistics address the numbers under supervision (both adults and juveniles), average caseload, terminations by method of termination, the average length of parole and percent with favorable outcome, and probationer and parolee profiles. Implications are drawn for current data collection efforts, and the appendix contains limited information on military prisons."

- Crime Solutions.gov

Crime Mapping

- NIJ Mapping and Analysis for Public Safety

Specialized sources of statistics/data

- Death Penalty Information Center

- Federal Sentencing Statistics

- The Counted: People Killed by Police in the US (The Guardian)

- Washington Post (People Shot Dead by Police)

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Protection's (OJJDP's) Statistical Briefing Book

- Stanford Open Policing Project Data on vehicle and pedestrian stops from law enforcement departments across the country.

- Corporate Prosecution Registry

- Police Crime Data

- Monitoring of Federal Criminal Sentences Series

- Citizen Police Data Project focused on Chicago

- Chicago Data Collaborative "Collaborative members collect data from institutions at all points of contact in the Cook County criminal justice system, including the Chicago Police Department, the Illinois State Police, the Office of the State's Attorney, and the Cook County Jail."

- Washington Post (Unsolved Homicide Database)

- American Violence Run by the NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management, the initial iteration of this databases includes city-level figures on murder rates in more than 80 of the largest 100 U.S. cities. According to the website, the second iteration will feature neighborhood-level figures on violent crime in 30-50 cities with available data.

- Police Data Initiative "This site provides a consolidated and interactive listing of open and soon-to-be-opened data sets that more than 130 local law enforcement agencies have identified as important to their communities, and provides critical and timely resources, including technical guidance and best practices, success stories, how-to articles and links to related efforts." See map of participating agencies" .

Other sources for statistics

- American Fact Finder

- See Judicial Workload, Jury Verdicts and Crime Statistics generally

- Harvard Dataverse more... less... The Harvard-MIT Data Center is the principal repository of quantitative social science data at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The majority of its holdings are available to Harvard and MIT affiliates directly via its web site through its search engine. Graduate students and faculty with a Harvard or MIT Library card can check out paper code books from libraries at either institution, under Harvard's and MIT's reciprocal borrowing agreement. In addition, the Data Center has negotiated a special agreement for undergraduates and summer graduate students, who are not covered by the standard agreement.

- Proquest Statistical Insight (Harvard Login) more... less... Proquest Statistical Insight is a bibliographic database that indexes and abstracts the statistical content of selected United States government publications, state government publications, business and association publications, and intergovernmental publications. The abstracts may also contain a link to the full text of the table and/or a link to the agency's web site where the full text of the publication may be viewed and downloaded.

- Data.gov Includes data from the Department of Justice and other agencies.

- Data Citation Index (Web of Science)

- Historical Statistics of the United States (Harvard Login) more... less... Presents the U.S. in statistics from Colonial times to the present. Included are statistics on U.S. population, including characteristics, vital statistics, internal and international migration. Statistics on work and welfare, economic structure and performance, economic sectors, and governance and international relations. Tables may be downloaded for use in spreadsheets and other applications. This electronic database is also in a five volume hard copy set.

Books, reports and articles about criminal justice statistics and records

- Data and Civil Rights: Criminal Justice Primer Part of larger conference on Data and Civil Rights http://www.datacivilrights.org/ ; includes write-up from conference http://www.datacivilrights.org/pubs/2014-1030/CriminalJustice-Writeup.pdf

- Ensuring the Quality, Credibility, and Relevance of U.S. Justice Statistics (2009)

- Estimating the Incidence of Rape and Sexual Assault

- Modernizing Crime Statistics: Report 1: Defining and Classifying Crime

Case Processing and Court Statistics

- Federal Criminal Case Processing Statistics

- State Court Caseload Statistics See also Data Collection: Court Statistics Project and CSP Data Viewer .

- Statistics and Reports (Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts)

Criminal Records

- Search Systems A mega search site with links to public records by state, county, city and also by record type. A great place to start your research. more... less... From the website: We've located, analyzed, described, and organized links to over 55,000 databases by type and location to help you find property, criminal, court, birth, death, marriage, divorce records, licenses, deeds, mortgages, corporate records, business registration, and many other public record resources quickly, easily, and for free.

- BRB Publications BRB Publications maintains a page with links to more than 300 local, state and federal websites offering free access to public records.

- National Sex Offender Public Registry From the US Department of Justice. This site also has links to all 50 states, District of Columbia, US territories, and tribal registry websites.

- FBI's Sex Offender Database websites An alternate source for state level sex offender databases.

- FBI's Bureau of Prisons Inmate Finder

- VINELink VINELink is the online version of VINE (Victim Information and Notification Everyday), the National Victim Notification Network. This service allows crime victims to obtain timely and reliable information about criminal cases and the custody status of offenders 24 hours a day.

Research Organizations and Advocacy Groups

- Vera Institute of Justice

- Agencies, Think Tanks and Advocacy Groups

- Urban Institute-Crime and Justice

- National Center for State Courts

- National Conference of State Legislatures

- Innocence Project

- Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice (UPenn Law)

- Capital Jury Project

Professional Organizations

- American Bar Association (Criminal Justice section)

- National District Attorneys Association

- American Correctional Association

- National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

Research guides from other libraries

- MSU Libraries, Criminal Justice Resources

- Georgetown Law Criminal Law and Justice Guide

- Harvard Kennedy School Library, Criminal Justice

- Criminal Law Prof Blog

- White Collar Crime Prof Blog

50-State-Surveys

- ABA Collateral Consequences Database

- National Conference of State Legislatures-Civil and Criminal Justice

HIstorical Archives/Projects

- National Death Penalty Archives

- ProQuest History Vault (Harvard Login)

Updates from popular criminal justice resources

New books in the library, new books in general.

- New Books Received at Rutgers

Ask Us! Submit a question or search the knowledge base.

Call Reference Desk, 617-495-4516

Text Ask a Librarian, 617-702-2728

Email research @law.harvard.edu

Meet Consult a Librarian

Classes View Training Calendar or Request an Insta-Class

Visit Us Library and Reference Hours

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/criminaljustice

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

A Hybrid approach on Tracking Criminal Investigation and Suspect Prediction

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

Criminal Investigation Research Paper

View sample criminal justice research paper on criminal investigation. Browse criminal justice research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

This research paper provides an overview of the criminal investigation process and investigative methods. The focus of the discussion is on definitional issues along with the identification and evaluation of the types and sources of information often used in criminal investigations.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, criminal investigation defined.

An investigation refers to the process of collecting information in order to reach some goal; for example, collecting information about the reliability and performance of a vehicle prior to purchase in order to enhance the likelihood of buying a good car. Applied to the criminal realm, a criminal investigation refers to the process of collecting information (or evidence) about a crime in order to: (1) determine if a crime has been committed; (2) identify the perpetrator; (3) apprehend the perpetrator; and (4) provide evidence to support a conviction in court. If the first three objectives are successfully attained, then the crime can be said to be solved. Several other outcomes such as recovering stolen property, deterring individuals from engaging in criminal behaviors, and satisfying crime victims have also been associated with the process.

A useful perspective on the criminal investigation process is provided by information theory (Willmer). According to information theory, the criminal investigation process resembles a battle between the police and the perpetrator over crime-related information. In committing the crime, the offender emits ‘‘signals,’’ or leaves behind information of various sorts (fingerprints, eyewitness descriptions, murder weapon, etc.), which the police attempt to collect through investigative activities. If the perpetrator is able to minimize the amount of information available for the police to collect, or if the police are unable to recognize the information left behind, then the perpetrator will not be apprehended and therefore, the perpetrator will win the battle. If the police are able to collect a significant number of signals from the perpetrator, then the perpetrator will be identified and apprehended, and the police win. This perspective clearly underscores the importance of information in a criminal investigation.

The major problem for the police in conducting a criminal investigation is that not only is there potentially massive amounts of information available, but the relevance of the information is often unknown, the information is often incomplete, and the information is often inaccurate. Further, to be useful in proving guilt in court (where beyond a reasonable doubt is the standard), the evidence must have certain other qualities, and certain rules and procedures must be followed in collecting the evidence.

The Structure of Criminal Investigations

Criminal investigations can be either reactive, where the police respond to a crime that has already occurred, or proactive, where the investigation may go on before and during the commission of the offense.

The reactive criminal investigation process can be organized into several stages. The first stage is initial discovery and response. Of course, before the criminal investigation process can begin, the police must discover that a crime occurred or the victim (or witness) must realize that a crime occurred and notify the police. In the vast majority of cases it is the victim that first realizes a crime occurred and notifies the police. Then, most often, a patrol officer is dispatched to the crime scene or the location of the victim.

The second stage, the initial investigation, consists of the immediate post-crime activities of the patrol officer who arrives at the crime scene. The tasks of the patrol officer during the initial investigation are to arrest the culprit (if known and present), locate and interview witnesses, and collect and preserve other evidence.

If the perpetrator is not arrested during the initial investigation, then the case may be selected for a follow-up investigation, the third stage of the reactive investigation process. The followup investigation consists of additional investigative activities performed on a case, and these activities are usually performed by a detective. The process of deciding which cases should receive additional investigative effort is referred to as case screening. This decision is most often made by a detective supervisor and is most often guided by consideration of the seriousness of the crime (e.g., the amount of property loss or injury to the victim) and solvability factors (key pieces of crime-related information that, if present, enhance the probability of an arrest being made) (Brandl; Brandl and Frank).

Finally, at any time in the process the case may be closed and investigative activities terminated (e.g., victim cancels the investigation, the crime is unfounded, there are no more leads available, or an arrest is made). If an arrest is made, or an arrest warrant is issued, primary responsibility for the case typically shifts to the prosecutor’s office. The detective then assists the prosecutor in preparing the case for further processing.

With regard to proactive criminal investigations, undercover investigations are of most significance (Marx). Perhaps the most well-known type of undercover strategy is the sting or buy-bust strategy that usually involves a police officer posing as someone who wishes to buy some illicit goods (e.g., sex, drugs). Once a seller is identified and the particulars of the illicit transaction are determined, police officers waiting nearby can execute an arrest. Another common strategy involves undercover police officers acting as decoys where the attempt is to attract street crime by presenting an opportunity to an offender to commit such crime (e.g., a police officer poses as a stranded motorist in a high crime area; when a robbery attempt is made, nearby officers can make an arrest). Undercover strategies are controversial primarily because of the possibility of entrapment. Although a multitude of court cases have dealt with this issue, the basic rule is that the police can provide the opportunity or can encourage the offender to act but cannot compel the behavior—a fine line indeed.

Sources of Information and Evidence in Criminal Investigations

As noted earlier, the major problem for the police in conducting criminal investigations is determining the utility of the information (evidence) collected. While much information may be discovered or otherwise available to the police, only a small portion of it may be accurate, complete, and relevant, and hence useful, in establishing the identity (and/or whereabouts) of the culprit. As discussed below, not all types of information are equal in this regard—some types of evidence are usually more useful than others.

Information from Physical Evidence

Physical evidence is evidence of a tangible nature relating directly to the crime. Physical evidence includes such items as fingerprints, blood, fibers, and crime tools (knife, gun, crowbar, etc.). Physical evidence is sometimes referred to as forensic or scientific evidence, implying that the evidence must be scientifically analyzed and the results interpreted in order to be useful.

Physical evidence can serve at least two important functions in the investigative or judicial process (Peterson et al.). First, physical evidence can help establish the elements of a crime. For example, pry marks left on a window (physical evidence) may help establish the occurrence of a burglary. Second, physical evidence can associate or link victims to crime scenes, offenders to crime scenes, victims to victims, instruments to crime scenes, offenders to instruments, and so on. For example, in a homicide case, a body of a young female was found along a rural road. Knotted around her neck was a black electrical cord (physical evidence). The cause of death was determined to be ligature strangulation via the electrical cord. Upon searching the area for evidence, an abandoned farmhouse was located and searched, and a piece of a similar electrical cord was found. This evidence led the investigators to believe that the farmhouse may have been where the murder actually occurred. Further examination of the scene revealed tire impressions from an automobile (more physical evidence). These tire impressions were subsequently linked to the suspect’s vehicle.

Most forensic or physical evidence submitted for analysis is intended to establish associations. It is important to note that physical evidence is generally not very effective at identifying a culprit when one is not already known. Typically the identity of the culprit is developed in some other way and then physical evidence is used to help establish proof of guilt. Possible exceptions to this pattern are fingerprints (when analyzed through AFIS or Automated Fingerprint Identification System technology) and DNA banks. With AFIS technology, fingerprints recovered from a crime scene can be compared with thousands of other prints on file in the computer system at the law enforcement agency. Through a computerized matching process, the computer can select fingerprints that are close in characteristics. In this way a match may be made and a suspect’s name produced.

DNA printing allows for the comparison of DNA obtained from human cells (most commonly blood and semen) in order to obtain a match between at least two samples. In order for traditional DNA analysis to be useful, a suspect must first be identified through some other means, so that a comparison of samples can be made. However, emerging technology involves the creation of DNA banks, similar to the computerized fingerprint systems, in order to compare and match DNA structures. There is little question, as technological capabilities advance, so too will the value of physical evidence.

Information from People

Beside physical evidence, another major source of information in a criminal investigation is people, namely witnesses and suspects. Witnesses can be classified as either primary or secondary. Primary witnesses are individuals who have direct knowledge of the crime because they overheard or observed its occurrence. This classification would include crime victims who observed or who were otherwise involved in the offense. Eyewitnesses would also be included here. Secondary witnesses possess information about related events before or after the crime. Informants (or street sources ) and victims who did not observe the crime would be best classified as secondary witnesses.

A suspect can be defined as any individual within the scope of the investigation who may be responsible for the crime. Note that a witness may be initially considered a suspect by the police because information is not available to rule him or her out as the one responsible for the crime.

Besides the basic information about the particulars of the criminal event and possibly the actions of the perpetrator (to establish a modus operandi), another important type of information often provided by witnesses is eyewitness descriptions and identifications. Such information is quite powerful in establishing proof—for the police, prosecutor, judge, and jury—but the problem is that eyewitness identifications are often quite inaccurate and unreliable (Loftus et al.). Research has shown that many factors—such as environmental conditions, physical and emotional conditions of the observer, expectancies of the observer, perceived significance of the event, and knowledge of the item or person being described—can significantly influence the accuracy of eyewitness statements.

Hypnosis and cognitive interviews are two investigative tools available in the interview setting for the purpose of enhancing memory recall, and thus enhancing the accuracy of eyewitness information. Hypnosis is typically viewed as an altered state of consciousness that is characterized by heightened suggestibility (Niehaus). For the police, hypnosis is used as a method of stimulating memory in an attempt to increase memory recall greater than that achieved otherwise. While the use of hypnosis has increased sharply in the 1990s many courts have refused to admit such testimony because of accuracy concerns, or have established strict procedures under which hypnotically elicited testimony must be obtained (e.g., interview must be videotaped, the hypnotist should know little or nothing about the particulars of the case, no other persons are to be present during the interview, etc.). Most problematic is that under hypnosis, one is more responsive to suggestions (by definition) and thus, the hypnotist (intentionally or not) may lead the subject and inaccurate information may result. Once again then, information is produced but it is unknown whether the information is accurate.

Another method used to enhance memory recall among witnesses involves the use of the cognitive interview (Niehaus). A cognitive interview is designed to fully immerse the subject in the situation once again, but through freedom of description not hypnosis. The subject is instructed to report everything he or she can think of no matter how trivial it may seem. The witness may be instructed to recount the incident in more than one order. The intent is to allow for a much deeper level of recollection than the traditional interview. Research has shown that the cognitive interview approach elicits significantly more accurate information than a standard police interview, which typically involves frequent interruptions of explanations and descriptions, includes many closed-ended and short answer questions, and involves the inappropriate or overly strict ordering of questions (Niehaus).

In contrast to interviews of witnesses, interrogations of suspects are often more accusatory in nature. Usually interrogations are more of a process of testing already developed information than of actually developing information. The ultimate objective in an interrogation is to obtain a confession (Zulawski and Wicklander).

For obvious reasons, offenders have great incentive to deceive investigators. Understanding this, there are several tools available to investigators who wish to separate truthful from deceptive information. First is the understanding of kinesic behavior, the use of body movement and posture to convey meaning (Walters). Although not admissible in court, information derived from an understanding and interpretation of body language can be quite useful in an investigation. The theory behind the study of nonverbal behavior is that lying is stressful and individuals try to cope with this stress through body positioning and movement.

Although no single behavior is always indicative of deception, there are patterns (Zulawski and Wicklander). For example, a deceptive subject will tend not to sit facing the interrogator with shoulders squared but will protect the abdominal region of the body (angled posture, crossed arms). Major body shifts are typical especially when asked incriminating questions; and use of manipulators (or created jobs) are also common among deceptive subjects (e.g., grooming gestures), as are particular eye movements (Zulawski and Wicklander).

Much like nonverbal behavior, verbal behavior can also provide information about the truthfulness of a suspect. For example, deceptive subjects tend to provide vague and confusing statements, talk very soft or mumble, provide premature explanations, focus on irrelevant (but truthful) points in an explanation, or may claim memory problems or have a selectively good memory. Of course, interpretations of nonverbal and verbal behaviors in terms of deception must consider individual, gender, and cultural differences in personal interaction.

The polygraph is a mechanical means of detecting deception. The polygraph is a machine that measures physiological responses to psychological phenomenon. The polygraph records blood pressure, pulse, breathing rate, and electro-dermal reactivity and changes in these factors when questioned. Interpretation of the resulting chart serves as the basis for a judgment about truthfulness. Once again, the theory is that a person experiences increased stress when providing deceptive information and the corresponding physiological responses can be detected, measured, and interpreted. While this general theory is well founded, the accuracy of the polygraph depends largely on the skill of the operator and the individual who interprets the results of the polygraph examination (Raskin). No one can be forced to take a polygraph and polygraph results are seldom admissible in court. Often investigators threaten suspects with a polygraph examination in order to judge the nature of their reaction to it, or to induce a confession (Raskin).

Other Sources of Information

Along with physical evidence, witnesses, and suspects, there are a number of other sources that can provide useful information in a criminal investigation. These include psychological profiling, crime analysis, and the general public.

In the last two decades, psychological profiling has received much media attention. It is often portrayed as a complicated yet foolproof method of crime solving. In reality, psychological profiling is not all that mysterious. Psychological profiling is a technique for identifying the major personality, behavioral, and background characteristics of an individual based upon an analysis of the crime(s) he or she has committed. The basic theory behind psychological profiling is that the crime reflects the personality and characteristics of the offender much like how clothes, home decorations, and the car you drive reflects, to some degree, your personality. And these preferences do not change, or do not change very much over time.

In constructing a psychological profile, the characteristics of the offender are inferred from the nature of the crime and the behaviors displayed. The elements of a psychological profile are essentially statements of probability as determined from previous crimes and crime patterns (Holmes). Profiles are best suited and most easily constructed in cases where the perpetrator shows indications of psychopathology such as lust and mutilation murder, sadistic rape, and motiveless fire setting.

The value of a psychological profile is that it can help focus an investigation or reduce the number of suspects being considered. In this respect, a psychological profile is much like most physical evidence; a psychological profile cannot identify a suspect when one is not already known. There has been very little systematic research that has documented the actual impact of psychological profiles on criminal investigations. In an internal examination by the F.B.I. (as reported in Pinizzotto, 1984), analysts examined 192 cases where profiling was conducted. Of these, 88 were solved. Of these 88 solved cases, in only 17 percent did a profile offer significant help. Given the limitations of psychological profiles, it is clear that they are not as useful as media depictions might suggest.

Crime analysis is another potentially powerful source of information in a criminal investigation. Simply defined, crime analysis is the process of identifying patterns or trends in criminal incidents. Various means can be used to reach such ends, from computer mapping technology to computer data banks. The Violent Criminal Apprehension Program (VI-CAP) of the Federal Bureau of Investigation is an example of an elaborate and sophisticated crime analysis system. When police departments are confronted with unsolved homicides, missing persons, or unidentified dead bodies, personnel in the department may complete a VI-CAP questionnaire, which asks for detailed information regarding the nature of the incident. These data are then sent to the F.B.I. and entered into the VI-CAP computer system, which is able to collate the data and possibly link crimes that occurred in different jurisdictions based on similarities in the crimes. This system, and similar intrastate systems, are designed to facilitate communication and sharing of information across agencies.

Finally, the general public is a potentially useful source of information in criminal investigations. As defined here, the public consists of people who have information relating to a particular crime or criminal but often cannot be identified through traditional methods (like a neighborhood canvass). Crime Solvers (or Crime Stoppers) tip lines and television shows such as America’s Most Wanted provide a method of disseminating information and encouraging individuals to come forward with information relating to particular crimes. Although once again, little systematic research has examined the actual effects of such strategies, information that has come from the general public through these sources has led to the solving of many crimes across the county (Rosenbaum; Nelson).

This discussion has provided an overview of the criminal investigation process and the role, function, and utility of various types and sources of evidence within the process. With these understandings, one may be able to better appreciate the complexities of criminal evidence and the criminal investigation process.

Bibliography:

- BRANDL, STEVEN ‘‘The Impact of Case Characteristics on Detectives’ Decision Making.’’ Justice Quarterly 10 (1993): 395–415.

- BRANDL, STEVEN, and FRANK, JAMES. ‘‘The Relationship Between Evidence, Detective Effort, and the Disposition of Burglary and Robbery Investigations.’’ American Journal of Police 13 (1994): 149–168.

- HOLMES, RONALD. Profiling Violent Crimes: An Investigative Tool. Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage, 1989.

- LOFTUS, ELIZABETH; GREENE, EDITH L.; and DOYLE, JAMES M. ‘‘The Psychology of Eyewitness Testimony.’’ In Psychological Methods in Criminal Investigation and Evidence. Edited by David C. Raskin. New York: Springer, 1989. Pages 3–45.

- MARX, GARY. Undercover: Police Surveillance in America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

- NELSON, SCOTT ‘‘Crime-Time Television.’’ F.B.I. Law Enforcement Bulletin, August 1989, pp. 1–9.

- NIEHAUS, JOE. Investigative Forensic Hypnosis. New York: CRC Press, 1998.

- PETERSON, JOSEPH; MIHAJLOVIC, STEVEN; and GILLILAND, MICHAEL. Forensic Evidence and the Police: The Effects of Scientific Evidence on Criminal Investigations. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, 1984.

- PINIZZOTTO, ANTHONY. ‘‘Forensic Psychology: Criminal Personality Profiling.’’ Journal of Police Science and Administration 12 (1984): 32–40.

- RASKIN, D. C. Psychological Methods in Criminal Investigation and Evidence. New York: Springer, 1989.

- ROSENBAUM, DENNIS. ‘‘Enhancing Citizen Participation and Solving Serious Crime: A National Evaluation of Crime Stoppers Program.’’ Crime and Delinquency 35 (1990): 401–420.

- WALTERS, STAN Principles of Kinesic Interview and Interrogation. New York: CRC Press, 1996.

- WILLMER, M. Crime and Information Theory. Edinburgh, Scotland: University of Edinburgh Press, 1970.

- ZULAWSKI, DAVID E., and WICKLANDER, DOUGLAS E. Practical Aspects of Interview and Interrogation. New York: Elsevier, 1992.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

One crime wave, three hypotheses: using interrupted time series to examine the unintended consequences of criminal justice reform, computer tablet recording of crime and a long-term hot spots policing programme

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 02 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Spencer P. Chainey 1 &

- Patricio R. Estévez-Soto 1

466 Accesses

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

After sustained reductions in robberies and thefts in 2016, the city of Montevideo, Uruguay, experienced a sudden increase in these crimes in late 2017. Using interrupted time series regressions, and controlling for seasonality using ARIMA models, we investigated three potential explanations for this increase: (1) the failure of a hot spots policing program to maintain crime decreases; (2) improved crime recording by police patrols using tablet computers; and (3) the change from an inquisitorial to an adversarial criminal justice procedure. We found that the hot spots policing program that began in April 2016 continued to be associated with crime reductions during 2017, that the increases observed after November 2017 were strongly associated with the new criminal justice procedure, and that tablets had a positive, albeit negligible, effect. The findings illustrate that criminal justice reforms, desirable as such reforms may be, can have unintended consequences on crime levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Offline crime bounces back to pre-COVID levels, cyber stays high: interrupted time-series analysis in Northern Ireland

Measuring the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on crime in a medium-sized city in China

Disentangling the Impact of Covid-19: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Crime in New York City

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In late 2017 and in to 2018, the capital city of Uruguay, Montevideo, experienced a sudden and substantial increase in robberies and thefts against pedestrians of over 45percent on the previous year (increasing from 15,093 of these crimes in 2017 to 21,984 in 2018). Although increases were observed in other types of crime, the increases in robberies and thefts were greater than those against property (e.g., domestic burglary) or crime in non-public settings (e.g., domestic violence). This increase in robberies and thefts was surprising because it came after a sustained period of decreases in these crimes that were associated with a large-scale hot spots policing program in Montevideo (Chainey et al. 2021 ). Faced with this increase in robberies and thefts in 2018, Uruguayan authorities began to question the long-term crime prevention effect of the hot spots policing programme (named Programa de Alta Dedicación Operativa, PADO) and whether the resourcing commitment to the programme should continue. In 2018, Montevideo also implemented two changes in police practice and criminal justice policy. These changes involved a transition to police officers using handheld computer tablets to record crimes and a nationwide change to an adversarial criminal justice procedure. Little consideration had been given to the possible influence of these two changes on the increase in robberies and thefts.

In this paper we examine three potential explanations for the increase in robberies and thefts in Montevideo in 2018: the increase in crime was associated with the reduced effectiveness of the PADO hot spots policing program; the increase in crime was associated with an increase in crime reporting and recording associated with the use of tablet computers, and the increase in crime was associated with the change in the criminal procedure code.

The research aims to make three contributions to the existing research literature. First, the findings from the study contribute new insights into the impact on crime levels from the adoption of an adversarial criminal procedure code in countries that previously operated inquisitorial criminal justice systems. A feature of the inquisitorial criminal justice system involves a suspect of a crime being sent to prison until their case is heard at a court of law and a conviction decision is reached. The adversarial system minimizes the use of pre-trial detention and instead involves conditional release mechanisms whereby suspects can return home and wait for their trial. Most countries have used adversarial criminal procedures for decades; however, in Latin America, many countries have historically followed an inquisitorial criminal procedure. In recent years, these Latin American countries, including Uruguay, have transitioned to adversarial procedures. Adversarial procedures have been implemented to improve the slow and abuse-prone criminal justice processes that the inquisitorial system is susceptible to. To date, very few studies have examined how these criminal justice reforms may have influenced changes in criminal behavior, and consequently, crime levels (see Zorro Medina et al. 2020 ; Huebert 2019 ). We examine the impact of the adoption of the adversarial criminal procedure code (implemented on the 1st November 2017) on changes in crime levels in Montevideo.

Second, we assess if the adoption of new technology for front-line policing can affect crime reporting and recording levels. While the scholarship on the adoption and use of mobile technologies in policing is an established field (e.g., Lindsay et al. 2009 ; Lum et al. 2017 ; Koper et al. 2014 ; Allen et al. 2008 ), the potential impact that these technologies could have on crime levels remains unexplored.

Third, we add to the evidence on the long-term impact of hot spots policing by considering these effects for a large city. To date, we know of only one study that has examined the long-term effects of hot spots policing, with this being for a small city in the USA (Koper et al. 2021 ). The current study examines if the hot spots policing programme in Montevideo was no longer effective in reducing crime after operating for over a year.

The rest of the article is structured as follows: First, we introduce the context of the study and briefly review the relevant literature. Then we describe the data and methods used. This is followed by the results. Lastly, we discuss the findings and limitations, and end with conclusions including those that relate to crime prevention.

Hot spots policing in Montevideo: PADO

PADO, introduced in April 2016 in Montevideo, was the first hot spots policing programme in Latin America that involved the use of a large number of police officers solely dedicated to patrolling hot spots (Inter-American Development Bank and the Uruguay Ministry of Interior 2017 ). PADO involved the precise targeted deployment of police patrols to the specific streets where robberies and thefts were known to concentrate. Prior to the implementation of PADO, robberies and thefts had been increasing in Montevideo by at least ten percent per year for almost a decade. In 2015, drawing from the international evidence on the effects of hot spots policing (Braga et al. 2014 ) and an analysis of the geographic and temporal patterns of robberies and thefts in Montevideo, the Uruguay Police implemented PADO in the top 120 hot spot locations in Montevideo (Chainey et al. 2021 ). This involved groups of two or three police officers patrolling each hot spot location on foot, supported by a small number of motorbike police patrols (about two motorbike patrols for every 15 foot patrols). The PADO patrols operated between 17.00 and 01.00 h (informed by a temporal analysis of the crime hot spots) and required the foot patrols to remain within their assigned patrol area for the evening. The exception to this was when a person was arrested by a PADO patrol, requiring one of the PADO patrol officers to accompany the police response team (that had been called to the scene) and the suspect to a local police station. For every 15 patrols, a supervisor was assigned to ensure the patrols were where they needed to be and to coordinate any support to specific hot spots during a patrol shift. Every day, over 400 police officers were dedicated to PADO.

The primary purpose of the PADO patrols was to act as a visible deterrent to offending behavior. Their purpose was not necessarily to be more active in making arrests, but instead to increase the perceived risk of offending in the locations where the foot patrols were deployed. It was rare for PADO foot patrol officers to make an arrest while on patrol, meaning their presence in the hot spot locations were maintained for the duration of their assignment. A quasi-experimental evaluation of PADO in 2016 showed the programme was responsible for a 23 percent decrease in robberies and thefts in PADO patrol areas compared to control areas, with no evidence of displacement to other areas or other crime types (Chainey et al. 2021 ). PADO continued throughout 2017 and 2018, with the same resourcing levels being maintained.

The implementation and use of tablet computers by police officers inMontevideo

To help improve the completion of administrative tasks while police officers were on patrol, in 2017 the Uruguay Police began the incremental roll out of tablet computers to police officers in Montevideo, including to PADO patrol officers. These tablets now meant that police officers could perform immediate identification checks of individuals and vehicles, and record offence details reported to them while they were in the field. The use of the tablets therefore made it potentially easier for victims to report crimes. Prior to the introduction of the tablets, crimes could only be reported at police stations. Tablets used by PADO patrol officers meant that victims could now report the offence to these patrol officers. This meant that robberies and thefts that may not have previously been reported because the victim decided not to visit a police station could more likely be reported. Also, the introduction of the tablets meant that when a PADO patrol officer did make an arrest, they did not need to accompany the person they had arrested to a local police station. Although arrests made by PADO officers were rare, the patrol officer could now complete the arrest details on the tablet and remain in their patrol location with their patrol colleagues.

After a period of pilot testing in 2017, a large roll out programme commenced in 2018 to equip all PADO patrol groups with at least one tablet. Hence, it was plausible that the increases in robberies and thefts experienced in 2018 were because of an increase in crime reporting to PADO officers while they were on patrol, rather than an actual increase in the incidence of robberies and thefts.

Uruguay’s new criminal procedure code

Since the 1990s, more than 20 countries in Latin America have transformed their justice systems by replacing inquisitorial procedures (inherited from colonial rule) with an adversarial model presided over by an impartial judiciary. This “criminal procedural revolution” (Zorro Medina et al. 2020 ) was implemented to modernize the region’s criminal justice systems. Its goals were to improve the efficiency of criminal justice processes by increasing clearance rates and shortening lengthy criminal procedures, and reducing abuses of the criminal justice system such as weak human rights protections that incentivized the use of torture to forcibly obtain confessions (Magaloni and Rodriguez 2020 ).

One of the aims of the transition from the inquisitorial to adversarial system was to reduce the use of pre-trial detention. Inquisitorial criminal justice systems rely on extensive secret pre-trial investigations and written records (rather than oral proceedings), lack alternatives to a formal trial (e.g., pre-trial diversions or plea bargains), and are overseen by judges who are responsible for prosecuting, defending and adjudicating cases (Hafetz 2003 ). As a consequence, pre-trial detention, referred to in Spanish as prisión preventiva (preventive detention), is a feature of the inquisitorial criminal justice system in Latin America. This involves a suspect (based on a judge’s decision) being sent immediately to prison until their case is heard at a court of law and conviction decision is reached. The aim of this was to reduce the risk of suspects interfering with criminal investigations or fleeing justice (Fondevila and Quintana-Navarrete 2021 ). As Hafetz ( 2003 ) notes “many unconvicted inmates spend several years behind bars awaiting a verdict… some remain in prison for a longer period than if they had been convicted of the crime itself” (p 1758). Around 30 to 85 percent of the incarcerated population in Latin American prisons constitute these suspects that have not been convicted (Fondevila and Quintana-Navarrete 2021 ). This incarceration violates human rights and additionally subjects suspects to dismal conditions in Latin American prisons such as overcrowding, violence, physical and sexual abuse, and malnutrition (Hafetz 2003 ; Fondevila and Quintana-Navarrete 2021 ).

In Uruguay, reform to an adversarial system aimed to improve the general efficiency of the country’s criminal justice system. This new system shifted the burden of proof to criminal prosecutors who are required to build and present cases before judges, who then rule on whether there are sufficient grounds to indict a suspect. The new system also aimed to minimize the use of pre-trial detention. In practice, the transition from prisión preventiva involved implementing conditional release mechanisms whereby suspects could return home and wait for their trial. On November 1, 2017, Uruguay replaced its inquisitorial system with the adversarial criminal procedure system. Before the implementation of this new criminal procedure code the percentage of all prison inmates in Uruguay that were in pre-trial detention (between 2000 and 2017) ranged between 94 and 63 percent of the prison population (Organisation of American States 2022 ). From November 1, 2017, suspects had a right to be given bail. Following this change, the percentage of the prison population that were suspects held in pre-trial detention decreased to 43 percent in 2018 and 22 percent in 2019 (Organisation of American States 2022 ).

Uruguay, like many other countries in Latin America, have implemented these criminal justice reforms to improve their previous inefficient and abuse-prone criminal justice systems. However, whether these reforms have unintended consequences on levels of crime is a topic that has received little attention. Certain empirical evidence does suggest that changes in criminal procedure codes do affect criminal behavior (for a review see Zorro Medina et al. 2020 ). The most notable of these is that the incarceration of offenders denies them of the ability to commit crime, which in turn reduces crime via their incapacitation (Cohen 1983 ). In an opposite manner, reductions in pre-trial detention could lead to increases in crime, because the incapacitation effect of pre-trial detention has been removed. Evidence from Colombia supports this hypothesis, where following the implementation of an adversarial criminal justice procedure, a 22 percent increase in crime was observed (Zorro Medina et al. 2020 ). We therefore hypothesize that one possible explanation for the increases in crime observed in Uruguay in 2018 was associated with the implementation the new adversarial criminal procedure code.

The current study tests three hypotheses for explaining the increase in robberies and thefts. First, we test if the increase in crime was associated with the reduced effectiveness of the PADO hot spots policing program. Second, we test if the introduction of tablet computers for recording offenses contributed to these increases in the recorded levels of robberies and thefts. Third, we test whether the transition to the adversarial criminal procedure system was associated with the increases in robberies and thefts. We examine each hypothesis using interrupted time series regression to detect whether changes in the levels of crime coincided with the timing of the changes in policing and criminal justice procedures we describe above.

Data and methods

We began the analysis using disaggregated data on every robbery and theft recorded in Montevideo between January 1, 2015, and November 25, 2018 ( n = 70,016). Incidents were aggregated by date into a daily time series covering the study period, consisting of 1425 daily observations. We then added two dummy variables to indicate the periods of interest: A “PADO” variable indicated whether the date was on or after April 11, 2016 (the date PADO began), and a “Justice” variable indicated whether the date was on or after November 1, 2017 (the day the new penal code came into force).

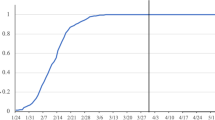

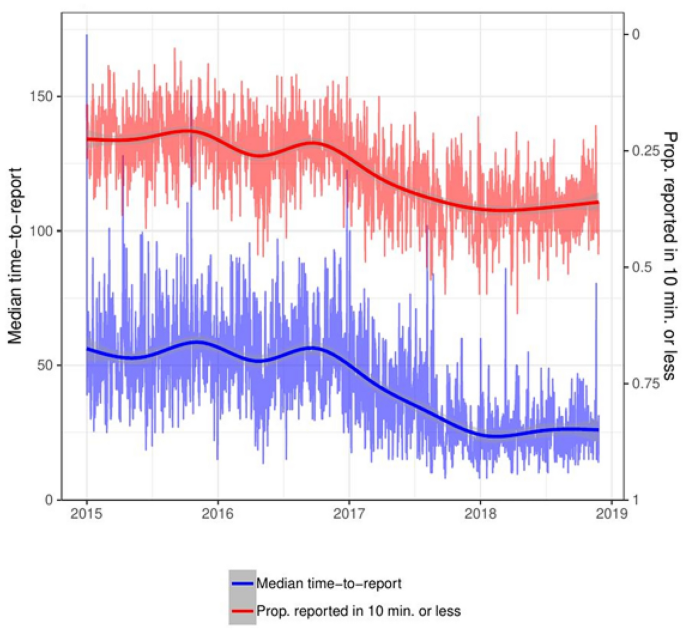

Tablets for recording crime were introduced in Montevideo over three stages. Between January and July 2017, the use of a small number of tablets was tested in Montevideo. From August to December 2017, the use of tablets incrementally increased, until January 2018 when the full roll out of tablets across Montevideo had been completed. The systematic recording of whether a crime had been recorded using a tablet only began in January 2018; however, two attributes captured in crime records prior to 2018 can be used as proxy variables to determine how many incidents were recorded using tablets. The first of these attributes was the median time (in minutes) that elapsed between when the robbery or theft occurred and when it was reported to the police. In 2018, the median time for a tablet-recorded robbery or theft to be reported was 6 min. In contrast, the median time-to-report for conventionally recorded robberies and thefts (that required the victim to visit a police station) was 66 min Chainey(Kruskal–Wallis \(\chi^{2} = 3769.2\) , \(df = 1\) , \(p < 0.001\) , \(n = 11,854\) ). On examining the median time-to-report per day, a clear trend emerged that coincided with the rollout of the tablets in Montevideo in 2017. This showed, see Fig. 1 , that before January 2017, the median time between when the crime occurred and when it was reported to the police was stable. During 2017, this median time began to decrease as tablets were being rolled out, until January 2018 when the median time between when the crime occurred and when it was reported stabilized, which coincides with the completion of the tablet rollout program.

Time series of the daily median time-to-report and the proportion of robberies and thefts reported in 10 min or less during the study period. Thick lines represent generalized additive model smooth trends

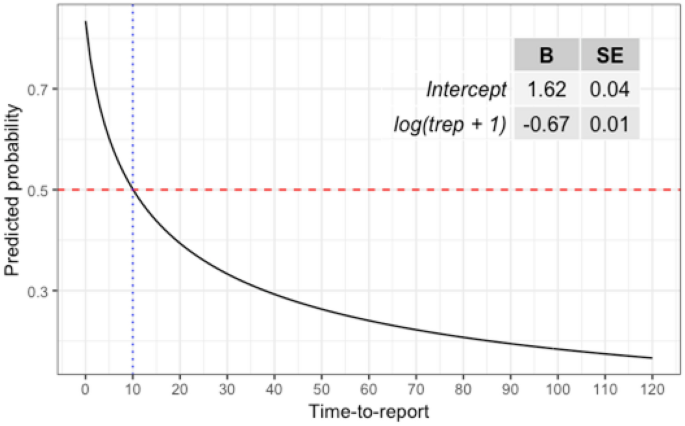

The second attribute we examined to determine the estimated number of robberies and thefts that were recorded using tablets was the proportion of robberies and thefts reported in 10 min or less per day. To identify the 10-min cutoff point, we fitted a logistic model to 2018 data using time-to-report to predict the odds of a crime being recorded using a tablet. This model found a significant and negative relationship between the time-to-report (log-transformed due to the highly skewed distribution of time-to-report) and the odds of a crime being recorded with a tablet (Wald χ _( df = 1)^2 = 2417.14, p < 0.001, see Fig. 2 for coefficient parameters). To identify the suitable cutoff point in minutes, we calculated predicted probabilities for 0 to 120 min in time-to-report and found that the probability of a crime being recorded in a tablet was greater than 50% when the time-to-report was 10 min or less (see Fig. 2 ). We then examined the trend in the daily proportion of robberies and thefts reported in 10 min and found that it matched the pattern of the median time-to-report, with proportions of robberies and thefts reported within 10 min increasing while tablets were being introduced in Montevideo (see Fig. 1 ).

Predicted probabilities of robberies and thefts being recorded on a tablet during 2018 conditional on the time-to-report. Coefficient estimates from the logistic model are shown in the table insert

To examine if the change in the criminal procedure code and the introduction of tablets for recording crime were associated with the increase in robberies and thefts experienced in Montevideo, we used interrupted time series (ITS) regression. ITS is used to evaluate the effects of macro-level interventions that have a clear implementation period. Lopez Bernal et al. ( 2017 ) provide a good theoretical and practical introduction to the technique. Essentially, an ITS is an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression in which the dependent variable ( \(y\) ) is primarily modeled as a function of time ( \(T\) ) with at least one dummy variable representing the implementation of an intervention ( \(x\) ) at \(T_{x}\) . Additionally, the model can include the effect of an interaction between \(x \times T\) to indicate a change in slope after the implementation of \(x\) . The general form of the ITS model is:

where \(\beta_{0}\) corresponds to the value of \(y\) when \(T = 0\) , \(\beta_{1}\) represents the baseline trend before the intervention of \(x\) , \(\beta_{2}\) represents the baseline change in \(y\) after the intervention \(x\) , \(\beta_{3}\) is the change in trend after the intervention, and \(e\) is an error term. We used two intervention dummies to control for the effects of PADO and the implementation of the new CJS ( \(x_{1} = {\text{PADO}}\) . and \(x_{2} = {\text{Justice}}\) ). Additionally, we used two models to separately control for the use of tablets ( \(x_{3t}\) ) using the daily median time-to-report (Model 1) and the proportion of robberies and thefts reported in 10 min or less (Model 2).

A crucial element of fitting an ITS model is to appropriately capture the underlying functional form of the trend as well as controlling for seasonal patterns. Crime trends are not always linear, thus more complex growth functions can be approximated using polynomial terms. We used second-order orthogonal polynomials to capture the underlying trend, as they were significantly better than a first-order polynomial ( F _( df = 2) = 20.4, p < 0.001). A model using third-order polynomials was not significantly better than a model using second-order polynomials ( F _( df = 2) = 0.2, p = 0.8). To control for seasonal effects, we first used OLS models with day of the week and week of the year dummy variables. However, when time series models experience residual autocorrelation (a common issue in time series analysis of crime events), the assumption of independence underpinning OLS is violated, leading to biased standard errors and potentially spurious inferences. Thus, to deal with residual autocorrelation we estimated linear models with ARIMA errors (Hyndman 2010 ; Hyndman and Athanasopoulos 2019 ). ARIMA errors are a powerful method to control for serial autocorrelation and can also be used to control for seasonal autocorrelation—providing a more flexible approach for controlling seasonality than the dummy variable approach we used in the OLS models. Therefore, in our ARIMA models we controlled seasonality using seasonal ARIMA components instead of day of the week and week of the year dummy variables.

A fundamental difference between OLS and the linear model with ARIMA errors is that the error term expressed in Eq. 1 ( \(e_{t}\) ) is not assumed to be independent and identically distributed, but is rather assumed to exhibit complex short-, medium-, and long-term dependencies (Box-Steffensmeier et al. 2014 ). The ARIMA model captures such dependencies by specifying the order of non-seasonal and seasonal autoregressive ( p ), integration ( d ), and moving average parameters ( q )—denoted as \({\text{ARIMA}}\left( {p,d,q} \right) \times \left( {P,D,Q} \right)_{m}\) —that are required to reduce the error term to a white noise process (Box-Steffensmeier et al. 2014 ; Estévez-Soto 2021 ). Formally, the errors are assumed to take the following form:

where \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) are the non-seasonal autoregressive and moving average parameters, \({\Theta }\) and \({\Phi }\) are the autoregressive and moving average parameters for a seasonal period of length \(m\) , \(B\) is the backshift operator, and \(z_{t}\) are white noise residuals (Estévez-Soto 2021 ). If (non-seasonal) integration is present, \(\phi \left( B \right)\) is replaced by \(\nabla^{d} \phi \left( B \right)\) , where \(\nabla\) is the differencing operator \(\left( {1 - B} \right){ }\) (Hyndman 2010 ; Hyndman and Athanasopoulos 2019 ). While a detailed discussion of ARIMA modeling is beyond the scope of this study, readers interested in technical details are directed to Box-Steffensmeier et al. ( 2014 ) and Hyndman and Athanasopoulos ( 2019 ).

Implementation of the linear models with ARIMA errors followed Estévez-Soto ( 2021 ), using Hyndman and Khandakar’s ( 2008 ) algorithm for automatically selecting ARIMA parameters that minimize the Akaike information criterion (AIC) as implemented by the ‘fable’ package (O’Hara-Wild et al. 2020 ) in R (R Core Team 2020 ).

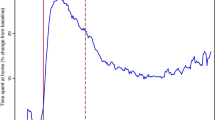

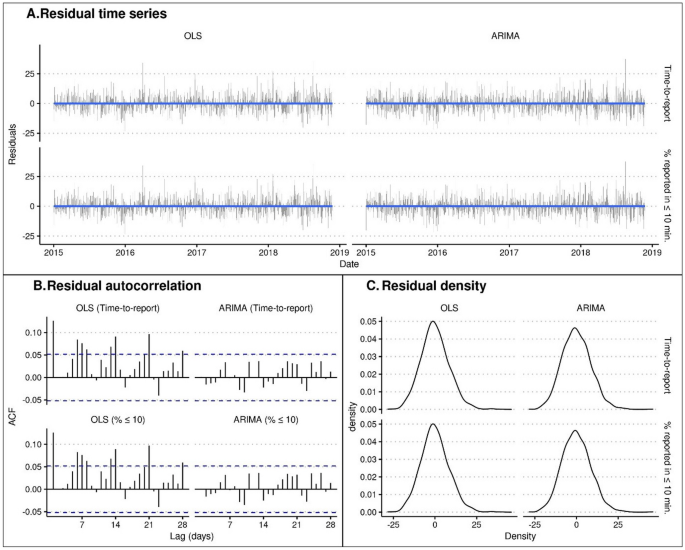

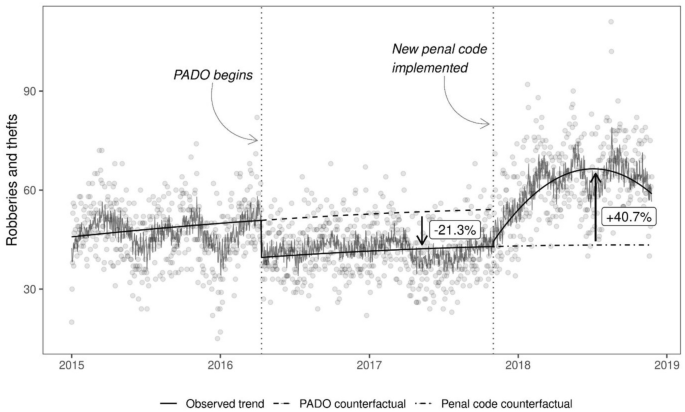

Model fits were assessed by inspecting model residuals visually and statistically. Visually, we inspected residual time series plots, residual autocorrelation plots, and residual density plots (see Fig. 3 ). Statistically, we used the Ljung–Box test (Ljung and Box 1978 ) to identify if there was statistically significant autocorrelation in the residuals, Engle’s ( 1982 ) ARCH test to rule out autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity, and KPSS tests (Kwiatkowski et al. 1992 ) to ensure residuals were stationary. These tests help diagnose if the models have captured the underlying temporal dependencies that could otherwise bias our results. Lastly, counterfactual trends were estimated for each intervention by calculating the values predicted by the estimated coefficients while holding the coefficient for the intervention dummy to zero (see Fig. 4 ).

Residual diagnostic plots for OLS and ARIMA error models

Plot with observed and counterfactual trends estimated by ARIMA model 2

In Table 1 , we report the results of the two specifications used: Model 1 used daily median time-to-report to control for the introduction of tablets, and Model 2 used the proportion of robberies and thefts reported in 10 min or less (expressed as a percentage). For each specification, we estimated coefficients using OLS and ARIMA methods. Reviewing first the model diagnostic results, OLS estimates consistently experienced a high degree of residual autocorrelation as evidenced by the significant Ljung–Box statistic (Ljung and Box 1978 ). Engle’s ( 1982 ) ARCH tests did not suggest the presence of autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity in either OLS or ARIMA estimates. KPSS tests (Kwiatkowski et al. 1992 ) suggested the residuals of all models were stationary. Further model diagnostics can be found in Fig. 3 , showing that the residual time series (Panel A) did not suggest neglected temporal patterns nor evidence of heteroscedasticity in all models. The autocorrelation plots (Fig. 3 : Panel B) confirm the results of the Ljung–Box tests, indicating residual autocorrelation in OLS residuals. The density plots (Fig. 3 : Panel C) suggest the residuals for all models were reasonably normal and centered around zero.

The results indicated that OLS residual autocorrelation was adequately captured by an ARIMA(2,0,1) x (2,0,1)[7] error model, thus we do not discuss OLS estimates in further detail. Overall, ARIMA estimates for Models 1 and 2 were similar. Both models indicated that the trend ( \(T\) and \(T^{2}\) ) in robberies and thefts before the implementation of PADO was not significant, meaning that robberies and thefts were stable at around 52 incidents per day in Montevideo after controlling for non-seasonal and seasonal autocorrelation. ARIMA estimates for the PADO variable were also similar for Models 1 and 2: In both cases the PADO variable was negative, of similar magnitude, and significant ( \(p < 0.01\) ). The models suggest that PADO was associated with 11.3 fewer robberies and thefts per day in Montevideo after its implementation in April 2016 to the end of October 2017. That is, in addition to the results reported by Chainey et al. ( 2021 ) on the significant reductions in robberies and thefts associated with PADO between April 2016 and December 2016, PADO continued to be associated with a consistent significant city-wide reduction in the daily average rate of robbery and thefts in Montevideo to the end of October 2017.