- Online Courses

- Unique Courses

- Scholarships

- Entrance Exams

- Study Abroad

- Question Papers

- Click on the Menu icon of the browser, it opens up a list of options.

- Click on the “Options ”, it opens up the settings page,

- Here click on the “Privacy & Security” options listed on the left hand side of the page.

- Scroll down the page to the “Permission” section .

- Here click on the “Settings” tab of the Notification option.

- A pop up will open with all listed sites, select the option “ALLOW“, for the respective site under the status head to allow the notification.

- Once the changes is done, click on the “Save Changes” option to save the changes.

10 Inspiring Quotes by Mahatma Gandhi, Essay on Non-violence of Mahatma Gandhi in 800 Words

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, also known as Mahatma Gandhi, is regarded as one of history's most inspirational leaders. His nonviolent struggle against British rule in India is well chronicled, and it inspired movements for civil rights and freedom around the world.

Throughout his life, Mahatma Gandhi worked for the rights and dignity of all people, using nonviolence as a way to win people over. He had used nonviolent resistance for the first time during a civil rights struggle in South Africa. For his empathy, humility, and words of wisdom that continue to inspire people all across the world, he earned the title Mahatma, which means "great soul."

Here are 10 quotes of Mahatma Gandhi that help inspire a healthy and fruitful living:

1. Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.

2. The weak can never forgive. Forgiveness is an attribute of the strong.

3. A coward is incapable of exhibiting love; it is the prerogative of the brave.

4. Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever.

5. Service which is rendered without joy helps neither the servant nor the served.

6. The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.

7. Glory lies in the attempt to reach one's goal and not in reaching it.

8. Whenever you are confronted with an opponent, conquer him with love.

9. An eye for an eye will only end up making the whole world blind.

10. It's the action, not the fruit of the action, that's important. You have to do the right thing. It may not be in your power, may not be in your time, that there'll be any fruit. But that doesn't mean you stop doing the right thing. You may never know what results come from your actions. But if you do nothing, there will be no result.

Essay on Non-violence of Mahatma Gandhi in 800 Words for class 4,5,6,7 and 8

Introduction.

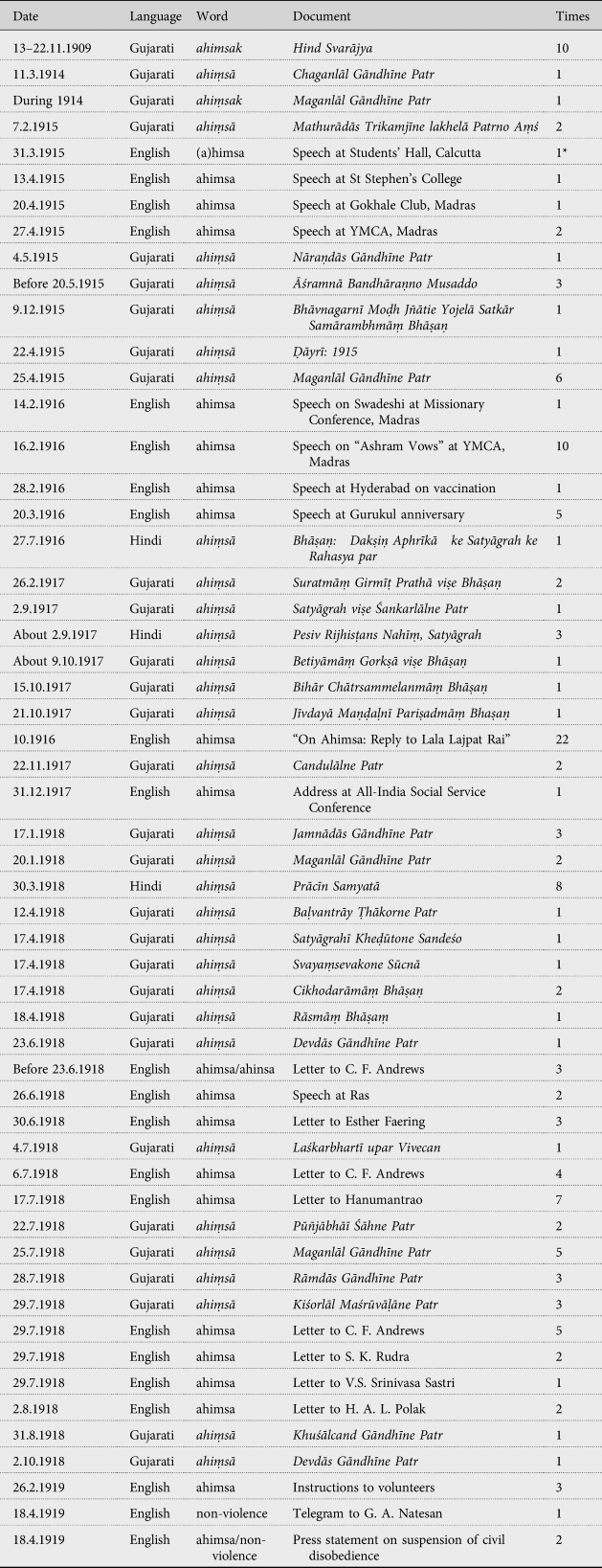

Nonviolence, often known as 'ahimsa,' is the discipline of avoiding purposely or accidentally harming others. It is a practice followed by famous saints such as Gautam Buddha and Mahaveer. Mahatma Gandhi was a forerunner in the practice of nonviolence. He employed nonviolence as a weapon against the British Empire's armed forces, assisting us in gaining independence without using a single weapon.

Nonviolence's Role in the Indian Freedom Struggle

After Mahatma Gandhi's engagement in the Indian freedom war, the role of nonviolence grew more important. Many violent freedom movements were taking place in the country at the same time, and their significance cannot be overstated. Our independence fighters who fought against British tyranny made numerous sacrifices. Nonviolence, on the other hand, was a peaceful protest that was a perfect approach to seek complete independence. Mahatma Gandhi used nonviolence in every anti-British movement. The following are Mahatma Gandhi's most major nonviolent movements that helped rock the foundations of the British administration.

Agitations in Champaran and Kheda

The British forced Champaran farmers to grow indigo and sell it at very low fixed prices again in 1917. Mahatma Gandhi launched a nonviolent protest against this practice, forcing Britishers to fulfill the farmers' demand.

Floods struck Kheda village in 1918, causing a catastrophic famine in the region. The British were unwilling to make any tax concessions or exemptions. For many months, Gandhiji developed a non-cooperation movement and led nonviolent rallies against the British authority. Finally, the administration was forced to give tax relief and temporarily cease revenue collection.

Movement Against Non-Cooperation

In 1920, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and harsh British policies sparked the Non-cooperation movement. It was a peaceful protest against British control. Gandhiji believed that the fundamental reason for Britishers' success in India was the support they received from Indians.

He urged people to shun British items in favor of 'Swadeshi' ones. Indians refused to work for the British and withdrew from British schools, civil services, government jobs, and so on. People began quitting from prominent positions, which had a significant impact on the British administration. The Non-Cooperation movement undermined the foundations of British control, and this without the employment of a single weapon. The non-cooperation movement exemplified the power of nonviolence.

Salt Satyagraha, also known as the Salt March

The Salt March, also known as the 'Namak Satyagrah,' was a nonviolent action spearheaded by Mahatma Gandhi to protest the British salt monopoly. The British put a high tariff on salt, which had an impact on local salt production. Gandhiji began a 26-day nonviolent march to Dandi village in Gujarat to protest the British government's salt monopoly.

The Dandi march began on March 12, 1930, from Sabarmati Ashram and finished on April 6, 1930, at Dandi, breaching British government salt rules and establishing local salt manufacture. The Salt March was a nonviolent movement that gained international notice and contributed to the establishment of Independent India.

Quit India Campaign

The foundation of the British government was profoundly shaken by the successful Salt March movement. On August 8, 1942, Mahatma Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement, which demanded that the British leave India. It was World War II, and Britain was already at war with Germany, and the Quit India Movement added fuel to the fire. A nationwide campaign of nonviolent civil disobedience was initiated, and Indians requested that they be removed from World War II.

The Quit India Movement had such an impact that the British administration agreed to grant India total independence after the war was finished. The Quit India Movement effectively put an end to British rule in India.

These Mahatma Gandhi-led movements were purely nonviolent and did not employ any weapons. The power of truth and nonviolence were employed to combat British control. The impact of nonviolence was so powerful that it drew the international community's immediate attention to the Indian independence cause. It aided in exposing the harsh policies and actions of British control to an international audience.

Weapons, according to Mahatma Gandhi, are not the only solution to any situation; in fact, they cause more problems than they solve. It is an instrument for spreading hatred, fear, and rage. Nonviolence is one of the best ways to battle far more powerful opponents without using a single weapon.

Apart from the independence movement, there are many modern-day examples that demonstrate the value of nonviolence and how it has aided in bringing about changes in society, all without spilling a single drop of blood. I hope the day does not come too soon when there will be no violence and all conflicts and disputes would be resolved peacefully without harming anyone or pouring blood, since this would be the greatest tribute to Mahatma Gandhi.

More MAHATMA GANDHI News

Budget 2024: Internship Opportunities to 1 Crore Youth at Top Companies

Budget 2024: Unlocking Entrepreneurial Potential Sitharaman Increases Mudra Loan Limit to 20 Lakh

Budget 2024-25: One Crore Farmers to Get Trained in Natural Farming Practices

- Don't Block

- Block for 8 hours

- Block for 12 hours

- Block for 24 hours

- Dont send alerts during 1 am 2 am 3 am 4 am 5 am 6 am 7 am 8 am 9 am 10 am 11 am 12 pm 1 pm 2 pm 3 pm 4 pm 5 pm 6 pm 7 pm 8 pm 9 pm 10 pm 11 pm 12 am to 1 am 2 am 3 am 4 am 5 am 6 am 7 am 8 am 9 am 10 am 11 am 12 pm 1 pm 2 pm 3 pm 4 pm 5 pm 6 pm 7 pm 8 pm 9 pm 10 pm 11 pm 12 am

Essay on Mahatma Gandhi – Contributions and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi

500+ words essay on mahatma gandhi.

Essay on Mahatma Gandhi – Mahatma Gandhi was a great patriotic Indian, if not the greatest. He was a man of an unbelievably great personality. He certainly does not need anyone like me praising him. Furthermore, his efforts for Indian independence are unparalleled. Most noteworthy, there would have been a significant delay in independence without him. Consequently, the British because of his pressure left India in 1947. In this essay on Mahatma Gandhi, we will see his contribution and legacy.

Contributions of Mahatma Gandhi

First of all, Mahatma Gandhi was a notable public figure. His role in social and political reform was instrumental. Above all, he rid the society of these social evils. Hence, many oppressed people felt great relief because of his efforts. Gandhi became a famous international figure because of these efforts. Furthermore, he became the topic of discussion in many international media outlets.

Mahatma Gandhi made significant contributions to environmental sustainability. Most noteworthy, he said that each person should consume according to his needs. The main question that he raised was “How much should a person consume?”. Gandhi certainly put forward this question.

Furthermore, this model of sustainability by Gandhi holds huge relevance in current India. This is because currently, India has a very high population . There has been the promotion of renewable energy and small-scale irrigation systems. This was due to Gandhiji’s campaigns against excessive industrial development.

Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence is probably his most important contribution. This philosophy of non-violence is known as Ahimsa. Most noteworthy, Gandhiji’s aim was to seek independence without violence. He decided to quit the Non-cooperation movement after the Chauri-Chaura incident . This was due to the violence at the Chauri Chaura incident. Consequently, many became upset at this decision. However, Gandhi was relentless in his philosophy of Ahimsa.

Secularism is yet another contribution of Gandhi. His belief was that no religion should have a monopoly on the truth. Mahatma Gandhi certainly encouraged friendship between different religions.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi has influenced many international leaders around the world. His struggle certainly became an inspiration for leaders. Such leaders are Martin Luther King Jr., James Beve, and James Lawson. Furthermore, Gandhi influenced Nelson Mandela for his freedom struggle. Also, Lanza del Vasto came to India to live with Gandhi.

The awards given to Mahatma Gandhi are too many to discuss. Probably only a few nations remain which have not awarded Mahatma Gandhi.

In conclusion, Mahatma Gandhi was one of the greatest political icons ever. Most noteworthy, Indians revere by describing him as the “father of the nation”. His name will certainly remain immortal for all generations.

Essay Topics on Famous Leaders

- Mahatma Gandhi

- APJ Abdul Kalam

- Jawaharlal Nehru

- Swami Vivekananda

- Mother Teresa

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

- Subhash Chandra Bose

- Abraham Lincoln

- Martin Luther King

FAQs on Mahatma Gandhi

Q.1 Why Mahatma Gandhi decided to stop Non-cooperation movement?

A.1 Mahatma Gandhi decided to stop the Non-cooperation movement. This was due to the infamous Chauri-Chaura incident. There was significant violence at this incident. Furthermore, Gandhiji was strictly against any kind of violence.

Q.2 Name any two leaders influenced by Mahatma Gandhi?

A.2 Two leaders influenced by Mahatma Gandhi are Martin Luther King Jr and Nelson Mandela.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Essay on Mahatma Gandhi in English for Children and Students

Table of Contents

Essay on Mahatma Gandhi in English: Mahatma Gandhi was an influential political leader in India who is best known for leading the country’s nonviolent resistance movement against British colonialism. After studying law in England, Gandhi returned to India and became a prominent leader of the Indian National Congress. He advocated for India’s independence from British rule and promoted a philosophy of non-violent resistance. Gandhi was arrested numerous times by the British authorities, but he continued to lead protests and campaigns against British rule. In 1947, India finally achieved independence, and Gandhi played a key role in the country’s transition to democracy. He was assassinated in 1948 by a Hindu extremist.

Fill Out the Form for Expert Academic Guidance!

Please indicate your interest Live Classes Books Test Series Self Learning

Verify OTP Code (required)

I agree to the terms and conditions and privacy policy .

Fill complete details

Target Exam ---

Below, we have provided simple essays on Mahatma Gandhi , a person who would always live in the heart of the Indian people. Every kid and child of India knows him by the name of Bapu, or Father of the Nation. Using the following Mahatma Gandhi essay, you can help your kids, and school-going children perform better in school during any competition or exam.

Long and Short Essay on Mahatma Gandhi in English

Below are short and long essays on Mahatma Gandhi in English for your information and knowledge.

The essays have been written in simple yet effective English so that you can quickly grasp and present the information whenever needed.

After going through these Mahatma Gandhi essays, you will learn about the life and ideals of Mahatma Gandhi, the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, what role he played in the freedom struggle, and why is he the most respected leader in the world over; how his birthday is celebrated, etc.

The information given in the essays will be helpful in speech giving, essay writing, or speech-providing competition on the occasion of Gandhi Jayanti.

Also Read: Independence Day Speech for Students

Mahatma Gandhi Essay 1 (100 words)

Mahatma Gandhi is famous in India as “Bapu” or “Rastrapita.” His full name of him is Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He was a great freedom fighter who led India as a leader of nationalism against British rule. He was born on the 2 nd of October in 1869 in Porbandar, Gujarat, India.

He died on the 30 th of January in 1948. M.K. Gandhi was assassinated by the Hindu activist Nathuram Godse, who was hanged later as a punishment by the government of India. Rabindranath Tagore has given him another name, “Martyr of the Nation,” since 1948.

Mahatma Gandhi Essay 2 (150 words)

Mahatma Gandhi is called Mahatma because of his great works and greatness throughout his life. He was a great freedom fighter and non-violent activist who always followed non-violence throughout his life while leading India to independence from British rule.

He was born on the 2 nd of October 1869 at Porbandar in Gujarat, India. He was just 18 years old while studying law in England. Later he went to the British colony of South Africa to practice his law, where he got differentiated from the light skin people because of being a dark skin person. That’s why he decided to become a political activist to make some positive changes in such unfair laws.

Later he returned to India and started a powerful and non-violent movement to make India an independent country. He was the one who led the Salt March (Namak Satyagrah or Salt Satyagrah or Dandi March) in 1930. He inspired many Indians to work against British rule for their independence.

Also Read: Sant Ravidas Jayanti 2024

Mahatma Gandhi Essay 3 (200 words)

Mahatma Gandhi was an outstanding personality in India who still inspires the people in the country and abroad through his legacy of greatness, idealness, and dignified life. Bapu was born in a Hindu family in Porbandar, Gujarat, India, on the 2 nd of October in 1869. The 2 nd of October was the great day for India when Bapu took birth. He paid an incredible and unforgettable role in the independence of India from British rule. The full name of the Bapu is Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He went to England for his law study just after passing his matriculation examination. Later he returned to India as a lawyer in 1890.

After he arrived in India, he started helping Indian people facing various problems from British rule. He started a Satyagraha movement against the British government to help Indians. Other significant movements initiated by the Bapu for the independence of India are the Non-cooperation movement in 1920, the Civil Dis the obedience movement in 1930, and the Quit India movement in 1942. All the movements had shaken the British rule in India and inspired many everyday Indian citizens to fight for freedom.

Mahatma Gandhi Essay 4 (250 words)

Bapu, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, was born 1869 on the 2 nd of October at Porbander in Gujarat, India. Mahatma Gandhi was a great Indian who led India in the independence movement against British rule. He completed his schooling in India and went to England for further study of law. He returned to India as a lawyer and started practicing law. He started helping the people of India who were humiliated and insulted by British rule.

He started the non-violence independence movement to fight against the injustice of Britishers. He was insulted many times but continued his non-violent struggle for the Independence of India. After his return to India, he joined Indian National Congress as a member. He was the great leader of the Indian independence movement who struggled a lot for the freedom of India. As a member of the Indian National Congress, he started independence movements like Non-Cooperation, Civil Disobedience, and later Quit India Movement, which became successful a day and helped India get freedom.

As a great freedom fighter, he got arrested and sent to jail many times, but he continued fighting against British rule for the justice of Indians. He was a great believer in non-violence and unity of people of all religions, which he followed through his struggle for independence. After many battles with many Indians, he finally became successful in making India an independent country on the 15 th of August in 1947. Later he was assassinated in 1948 on the 30 th of January by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu activist.

Mahatma Gandhi Essay 5 (300 words)

Mahatma Gandhi was a great freedom fighter who spent his whole life in a struggle for the independence of India. He was born in an Indian Hindu family on the 2 nd of October in 1869 in Porbander, Gujarat. He lived his whole as a leader of the Indian people. His whole life story is a great inspiration for us. He is called the Bapu or Rashtrapita as he spent his life fighting against British rule for our freedom of us. While fighting with Britishers, he took the help of his great weapons like non-violence and Satyagraha movements to achieve independence. He was arrested and sent to jail many times but never discouraged himself and continued fighting for national freedom.

He is the birth father of our nation who used all his power to make us free from British rule. He understood the power of unity in people (from different castes, religions, communities, races, ages, or gender), which he used throughout his independence movement. Finally, he forced Britishers to quit India forever through his mass movements on the 15 th of August in 1947. Since 1947, India’s 15th of August has been celebrated as Independence Day th of August has been celebrated as Independence Day in India.

He could not continue his life after the independence of India in 1947 as he was assassinated by one of the Hindu activists, Nathuram Godse, in 1948 on the 30 th of January. He was a great personality who served his whole life till death for the motherland. He enlightened our life with the true light of freedom from British rule. He proved that everything is possible with the non-violence and unity of people. Even after dying many years ago, he is still alive in the heart of every Indian as a “Father of the Nation and Bapu.”

Mahatma Gandhi Essay 6 (400 words)

Mahatma Gandhi is well known as the “Father of the Nation or Bapu” because of his most significant contributions toward our country’s independence. He was the one who believed in the non-violence and unity of the people and brought spirituality to Indian politics. He worked hard the remove the untouchability in the Indian society , upliftment of the backward classes in India, raised his voice to develop villages for social development, and inspired Indian people to use swadeshi goods and other social issues. He brought familiar people in front to participate in the national movement and encouraged them to fight for their actual freedom.

He was one of the persons who converted people’s dream of independence into truth day through his noble ideals and supreme sacrifices. He is remembered for his wondrous works and primary virtues such as non-violence, truth, love, and fraternity. He was not born as excellent, but he made himself great through his hard struggles and work. The life of King Harischandra highly influenced him from the play titled Raja Harischandra. After schooling, he completed his law degree in England and began his career as a lawyer. He faced many difficulties in his life but continued walking as a great leader.

He started many mass movements like the Non-cooperation movement in 1920, the civil disobedience movement in 1930, and finally the Quit India Movement in 1942, throughout the way to independence of India. After many struggles and work, the British Government finally granted independence to India. He was a straightforward person who worked to remove the color barrier and caste barrier. He also worked hard to remove the untouchability in the Indian society and named untouchables as “Harijan” means the people of God.

He was a great social reformer and Indian freedom fighter who died a day after completing his aim of life. He inspired Indian people for the manual labour and said that arrange all the resource ownself for living a simple life and becoming self-dependent. He started weaving cotton clothes through the use of Charakha in order to avoid the use of videshi goods and promote the use of Swadeshi goods among Indians.

He was a strong supporter of the agriculture and motivated people to do agriculture works. He was a spiritual man who brought spirituality to the Indian politics. He died in 1948 on 30 th of January and his body was cremated at Raj Ghat, New Delhi. 30 th of January is celebrated every year as the Martyr Day in India in order to pay homage to him.

Essay on Non-violence of Mahatma Gandhi – Essay 7 (800 Words)

Introduction

Non-violence or ‘ahimsa’ is a practice of not hurting anyone intentionally or unintentionally. It is the practice professed by great saints like Gautam Buddha and Mahaveer. Mahatma Gandhi was one of the pioneer personalities to practice non-violence. He used non-violence as a weapon to fight the armed forces of the British Empire and helped us to get independence without lifting a single weapon.

Role of Non-violence in Indian Freedom Struggle

The role of non-violence in the Indian freedom struggle became prominent after the involvement of Mahatma Gandhi. There were many violent freedom struggles going on concurrently in the country and the importance of these cannot be neglected either. There were many sacrifices made by our freedom fighters battling against the British rule. But non-violence was a protest which was done in a very peaceful manner and was a great way to demand for the complete independence. Mahatma Gandhi used non-violence in every movement against British rule. The most important non-violence movements of Mahatma Gandhi which helped to shake the foundation of the British government are as follows.

- Champaran and Kheda Agitations

In 1917 the farmers of Champaran were forced by the Britishers to grow indigo and again sell them at very cheap fixed prices. Mahatma Gandhi organized a non-violent protest against this practice and Britishers were forced to accept the demand of the farmers.

Kheda village was hit by floods in 1918 and created a major famine in the region. The Britishers were not ready to provide any concessions or relief in the taxes. Gandhiji organized a non-cooperation movement and led peaceful protests against the British administration for many months. Ultimately the administration was forced to provide relief in taxes and temporarily suspended the collection of revenue.

- Non-cooperation Movement

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre and the harsh British policies lead to the Non-cooperation movement in 1920. It was the non-violence protest against the British rule. Gandhiji believed that the main reason of the Britishers flourishing in India is the support they are getting from Indians. He pleaded to boycott the use of British products and promoted the use of ‘Swadeshi’ products. Indians denied working for the Britishers and withdrew themselves from the British schools, civil services, government jobs etc. People started resigning from the prominent posts which highly affected the British administration. The Non-Cooperation movement shook the foundation of the British rule and all these without a single use of any weapon. The power of non-violence was more evident in the non-cooperation movement.

- Salt Satyagrah or Salt March

Salt March or the ‘Namak Satyagrah’ was the non-violence movement led by Mahatma Gandhi against the salt monopoly of the Britishers. Britishers imposed a heavy taxation on the salt produce which affected the local salt production. Gandhiji started the 26 days non-violence march to Dandi village, Gujarat protesting against the salt monopoly of the British government. The Dandi march was started on 12 th March 1930 from Sabarmati Ashram and ended on 06 th April 1930 at Dandi, breaking the salt laws of the British government and starting the local production of salt. The Salt March was a non violent movement which got the international attention and which helped to concrete the foundation of Independent India.

- Quit India Movement

After the successful movement of the Salt March, the foundation of British government shook completely. Quit India Movement was launched by Mahatma Gandhi on 8 th August 1942 which demanded the Britishers to quit India. It was the time of World War II when Britain was already in war with Germany and the Quit India Movement acted as a fuel in the fire. There was a mass non-violent civil disobedience launched across the country and Indians also demanded their separation from World War II. The effect of Quit India Movement was so intense that British government agreed to provide complete independence to India once the war gets over. The Quit India Movement was a final nail in the coffin of the British rule in India.

These movements led by Mahatma Gandhi were completely Non-violent and did not use any weapon. The power of truth and non-violence were the weapons used to fight the British rule. The effect of non-violence was so intense that it gained the immediate attention of the international community towards the Indian independence struggle. It helped to reveal the harsh policies and acts of the British rule to the international audience.

Mahatma Gandhi always believed that weapons are not the only answer for any problem; in fact they created more problems than they solved. It is a tool which spreads hatred, fear and anger. Non-violence is one of the best methods by which we can fight with much powerful enemies, without holding a single weapon. Apart from the independence struggle; there are many incidents of modern times which exhibited the importance of non-violence and how it helped in bringing changes in the society and all that without spilling a single drop of blood. Hope the day is not very far when there will be no violence and every conflict and dispute will be solved through peaceful dialogues without harming anyone and shedding blood and this would be a greatest tribute to Mahatma Gandhi.

Long Essay on Mahatma Gandhi – Essay 8 (1100 Words)

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi aka ‘Mahatma Gandhi’ was one of the great sons of Indian soil who rose to become a great soul and gave major contribution in the great Indian freedom struggle against the British rule in India. He was a man of ideologies and a man with great patience and courage. His non-violence movements involved peaceful protests and non-cooperation with the British rule. These movements had a long term effects on the Britishers and it also helped India to grab the eye balls of global leaders and attracted the attention on the international platforms.

Family and Life of Mahatma Gandhi

- Birth and Childhood

Mahatma Gandhi was born as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi on 02 nd October, 1869 at Porbandar (which is in the current state of Gujarat). His father Karamchand Gandhi was working as the Chief Minister (diwan) of Porbandar at that time. His mother Putlibai was a very devotional and generous lady. Young Gandhi was a reflection of his mother and inherited high values, ethics and the feeling of sacrifice from her.

- Marriage and Education

Mohandas was married to Kasturba Makanji at a very young age of 13. In 1888, they were blessed with a baby boy and after which he sailed to London for higher studies. In 1893, he went to South Africa to continue his practice of law where he faced strong racial discrimination by the Britishers. The major incident which completely changed the young Gandhi was when he was forcibly removed from the first class compartment of a train due to his race and color.

- Civil Rights Movement in Africa

After the discrimination and embracement faced by Gandhi due to his race and color, he vowed to fight and challenge the racial discrimination of immigrants in South Africa. He formed Natal Indian Congress in 1894 and started fighting against racial discrimination. He fought for the civil rights of the immigrants in South Africa and spent around 21 years there.

- Mahatma Gandhi in the Indian Freedom Struggle

Gandhi returned to India in 1915 and joined Indian National Congress and started to raise voice against the British rule in India and demanded the complete independence or ‘Purn Swaraj’ for India. He started many non-violent movements and protests against Britishers and was also imprisoned various times in his long quest of freedom. His campaigns were completely non-violent without the involvement of any force or weapons. His ideology of ‘ahimsa’ meaning not to injure anyone was highly appreciated and was also followed by many great personalities around the globe.

Why was Gandhi called Mahatma?

‘Mahatma’ is a Sanskrit word which means ‘great soul’. It is said that it was Rabindranth Tagore who first used ‘Mahatma’ for Gandhi. It was because of the great thoughts and ideologies of Gandhi which made people honour him by calling ‘Mahatma Gandhi’. The great feeling of sacrifice, love and help he showed throughout his life was a matter of great respect for each citizen of India.

Mahatma Gandhi showed a lifelong compassion towards the people affected with leprosy. He used to nurse the wounds of people with leprosy and take proper care of them. In the times when people used to ignore and discriminate people with leprosy, the humanitarian compassion of Gandhi towards them made him a person with great feelings and a person with great soul justifying himself as Mahatma.

Mahatma Gandhi’s contribution on various social issues could never be ignored. His campaign against untouchability during his imprisonment in the Yerwada Jail where he went on fast against the age old evil of untouchability in the society had highly helped the upliftment of the community in the modern era. Apart from this, he also advocated the importance of education, cleanliness, health and equality in the society. All these qualities made him a man with great soul and justify his journey from Gandhi to Mahatma.

What are Gandhi’s accomplishments?

Mahatma Gandhi was a man with mission who not only fought for the country’s independence but also gave his valuable contribution in uprooting various evils of the society. The accomplishments of Mahatma Gandhi is summarized below:

- Fought against Racial Discrimination in South Africa

The racial discrimination in South Africa shocked Mahatma Gandhi and he vowed to fight against it. He challenged the law which denied the voting rights of the people not belonging to the European region. He continued to fight for the civil rights of the immigrants in South Africa and became a prominent face of a civil right activist.

- Face of the Indian Freedom Struggle

Mahatma Gandhi was the liberal face of independence struggle. He challenged the British rule in India through his peaceful and non-violent protests. The Champaran Satyagrah, Civil Disobedience Movement, Salt March, Quit India Movement etc are just the few non-violent movements led by him which shook the foundation of the Britishers in India and grabbed the attention of the global audience to the Indian freedom struggle.

- Uprooting the Evils of Society

Gandhi Ji also worked on uprooting various social evils in the society which prevailed at that time. He launched many campaigns to provide equal rights to the untouchables and improve their status in the society. He also worked on the women empowerment, education and opposed child marriage which had a long term effect on the Indian society.

What was Gandhi famous for?

Mahatma Gandhi was one of the great personalities of India. He was a man with simplicity and great ideologies. His non-violent way to fight a much powerful enemy without the use of a weapon or shedding a single drop of blood surprised the whole world. His patience, courage and disciplined life made him popular and attracted people from every corners of the world.

He was the man who majorly contributed in the independence of India from the British rule. He devoted his whole life for the country and its people. He was the face of the Indian leadership on international platform. He was the man with ethics, values and discipline which inspires the young generation around the globe even in the modern era.

Gandhi Ji was also famous for his strict discipline. He always professed the importance of self discipline in life. He believed that it helps to achieve bigger goals and the graces of ahimsa could only be achieved through hard discipline.

These qualities of the great leader made him famous not only in India but also across the world and inspired global personalities like Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King.

Mahatma Gandhi helped India to fulfill her dream of achieving ‘Purna Swaraj’ or complete independence and gave the country a global recognition. Though he left this world on 30 th January, 1948, but his ideologies and thoughts still prevail in the minds of his followers and act as a guiding light to lead their lives. He proved that everything is possible in the world if you have a strong will, courage and determination.

Get More Information About Mahatma Gandhi and his involvement

FAQs on Mahatma Gandhi

Who is Mahatma Gandhi?

Mahatma Gandhi was an influential political leader in India who is best known for leading the country's non-violent resistance movement against British colonialism.

Write Mahatma Gandhi essay in english?

Mahatma Gandhi was a man with mission who not only fought for the country’s independence but also gave his valuable contribution in uprooting various evils of the society.

When is Gandhi Jayanti?

The birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi is celebrated as Gandhi Jayanti. It is on 2nd October.

Who was Kasturba?

Kasturba was Gandhi's wife. He was married to Kasturba at a very young age of 13.

Related content

Talk to our academic expert!

Language --- English Hindi Marathi Tamil Telugu Malayalam

Get access to free Mock Test and Master Class

Register to Get Free Mock Test and Study Material

Offer Ends in 5:00

Please select class

ARTICLES : Peace, Nonviolence, Conflict Resolution

Read articles written by very well-known personalities and eminent authors about their views on gandhi, gandhi's works, gandhian philosophy of peace, nonviolence and conflict resolution..

- Articles on Gandhi

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Peace, Nonviolence, Conflict Resolution : Gandhi's Philosophy of Nonviolence

Peace, Nonviolence, Conflict Resolution

- Nonviolence and Multilateral Diplomacy

- Ahimsa: Its Theory and Practice in Gandhism

- Non-violent Resistance and Satyagraha as Alternatives to War - The Nazi Case

- Thanatos, Terror and Tolerance: An Analysis of Terror Management Theory and a Possible Contribution by Gandhi

- Yoga as a Tool in Peace Education

- Forgiveness and Conflict Resolution

Gandhi's Philosophy of Nonviolence

- Global Nonviolence Network

- Violence And Its Dimensions

- Youth, Nonviolence And Gandhi

- Nonviolent Action: Some Dilemmas

- The Meaning of Nonviolence

- India And The Anglo-Boer War

- Gandhi's Vision of Peace

- Gandhi's Greatest Weapon

- Conflict Resolution: The Gandhian Approach

- Kingian Nonviolence : A Practical Application in Policing

- Pilgrimage To Nonviolence

- Peace Paradigms: Five Approaches To Peace

- Interpersonal Conflict

- Moral Equivalent of War As A Conflict Resolution

- Conflict, Violence And Education

- The Emerging Role of NGOs in Conflict Resolution

- Role of Academics in Conflict Resolution

- The Role of Civil Society in Conflict Resolution

- Martin Luther King's Nonviolent Struggle And Its Relevance To Asia

- Terrorism: Counter Violence is Not the Answer

- Gandhi's Vision and Technique of Conflict Resolution

- Three Case Studies of Nonviolence

- How Nonviolence Works

- The Courage of Nonviolence

- Conflict Resolution and Peace Possibilities in the Gandhian Perspective

- An Approach To Conflict Resolution

- Non-violence: Neither A Beginning Nor An End

- Peacemaking According To Rev. Dr.Martin Luther King Jr.

- The Truth About Truth Force

- The Development of A Culture of Peace Through Elementary Schools in Canada

- Gandhi, Christianity And Ahimsa

- Issues In Culture of Peace And Non-violence

- Solution of Violence Through Love

- Developing A Culture of Peace And Non-Violence Through Education

- Nonviolence And Western Sociological And Political Thought

- Gandhi After 9/11: Terrorism, Violence And The Other

- Conflict Resolution & Peace: A Gandhian Perspective

- A Gandhian Approach To International Security

- Address To the Nation: Mahatma Gandhi Writes on 26 January 2009

- Truth & Non-violence: Gandhiji's Tenets for Passive Resistance

- The Experiments of Gandhi: Nonviolence in the Nuclear Age

- Terrorism And Gandhian Non-violence

- Reborn in Riyadh

- Satyagraha As A Peaceful Method of Conflict Resolution

- Non-violence : A Force for Radical Change

- Peace Approach : From Gandhi to Galtung and Beyond

- Gandhian Approach to Peace and Non-violence

- Locating Education for Peace in Gandhian Thought

Further Reading

(Complete Book available online)

- Conflict Resolution And Gandhian Ethics - By Thomas Weber

- A Contemporary Interpretation of Ahimsa

- The Tradition of Nonviolence and its Underlying Forces

- A Study of the Meanings of Nonviolence

- Notes on the Theory of Nonviolence

- Nonviolence as a Positive Concept

- Experimentation in Nonviolence: The Next Phase

- The Best Solver of Conflicts

- War and What Price Freedom

- A Coordinated Approach to Disarmament

- A Disarmament Adequate to Our Times

- The Impact of Gandhi on the U.S. Peace Movement

- The Grass-roots of World Peace

- Is There a Nonviolent Road to a Peaceful World?

- Nuclear Explosions and World Peace

- Aspects of Nonviolence in American Culture

- The Gandhian Way and Nuclear War

- A Nonviolent International Authority

Extrernal Links

- Gandhi, The Jews And Palestine A Collection of Articles, Speeches, Letters and Interviews Compiled by: E. S. Reddy

With Gandhi, the notion of nonviolence attained a special status. He not only theorized on it, he adopted nonviolence as a philosophy and an ideal way of life. He made us understand that the philosophy of nonviolence is not a weapon of the weak; it is a weapon, which can be tried by all.

Nonviolence was not Gandhi's invention. He is however called the father of nonviolence because according to Mark Shepard, "He raised nonviolent action to a level never before achieved." 1 Krishna Kripalani again asserts "Gandhi was the first in Human history to extend the principle of nonviolence from the individual to social and political plane." 2 While scholars were talking about an idea without a name or a movement, Gandhi is the person who came up with the name and brought together different related ideas under one concept: Satyagraha. Gandhi's View of Violence / Nonviolence Gandhi saw violence pejoratively and also identified two formsof violence; Passive and Physical, as we saw earlier. The practice of passive violence is a daily affair, consciously and unconsciously. It is again the fuel that ignites the fire of physical violence. Gandhi understands violence from its Sanskrit root, "himsa", meaning injury. In the midst of hyper violence, Gandhi teaches that the one who possess nonviolence is blessed. Blessed is the man who can perceive the law of ahimsa (nonviolence) in the midst of the raging fire of himsa all around him. We bow in reverence to such a man by his example. The more adverse the circumstances around him, the intenser grows his longing for deliverance from the bondage of flesh which is a vehicle of himsa... 3 Gandhi objects to violence because it perpetuates hatred. When it appears to do 'good', the good is only temporary and cannot do any good in the long run. A true nonviolence activist accepts violence on himself without inflicting it on another. This is heroism, and will be discussed in another section. When Gandhi says that in the course of fighting for human rights, one should accept violence and self-suffering, he does not applaud cowardice. Cowardice for him is "the greatest violence, certainly, far greater than bloodshed and the like that generally go under the name of violence." 4 For Gandhi, perpetrators of violence (whom he referred to as criminals), are products of social disintegration. Gandhi feels that violence is not a natural tendency of humans. It is a learned experience. There is need for a perfect weapon to combat violence and this is nonviolence.Gandhi understood nonviolence from its Sanskrit root "Ahimsa". Ahimsa is just translated to mean nonviolence in English, but it implies more than just avoidance of physical violence. Ahimsa implies total nonviolence, no physical violence, and no passive violence. Gandhi translates Ahimsa as love. This is explained by Arun Gandhi in an interview thus; "He (Gandhi) said ahimsa means love. Because if you have love towards somebody, and you respect that person, then you are not going to do any harm to that person." 5 For Gandhi, nonviolence is the greatest force at the disposal of mankind. It is mightier than any weapon of mass destruction. It is superior to brute force. It is a living force of power and no one has been or will ever be able to measure its limits or it's extend.Gandhi's nonviolence is the search for truth. Truth is the most fundamental aspect in Gandhi's Philosophy of nonviolence. His whole life has been "experiments of truth". It was in this course of his pursuit of truth that Gandhi discovered nonviolence, which he further explained in his Autobiography thus "Ahimsa is the basis of the search for truth. I am realizing that this search is vain, unless it is founded on ahimsa as the basis." 6 Truth and nonviolence are as old as the hills.For nonviolence to be strong and effective, it must begin with the mind, without which it will be nonviolence of the weak and cowardly. A coward is a person who lacks courage when facing a dangerous and unpleasant situation and tries to avoid it. A man cannot practice ahimsa and at the same time be a coward. True nonviolence is dissociated from fear. Gandhi feels that possession of arms is not only cowardice but also lack of fearlessness or courage. Gandhi stressed this when he says; "I can imagine a fully armed man to be at heart a coward. Possession of arms implies an element of fear, if not cowardice but true nonviolence is impossibility without the possession of unadulterated fearlessness." 7 In the face of violence and injustice, Gandhi considers violent resistance preferable to cowardly submission. There is hope that a violent man may someday be nonviolent, but there is no room for a coward to develop fearlessness. As the world's pioneer in nonviolent theory and practice, Gandhi unequivocally stated that nonviolence contained a universal applicability. In his letter to Daniel Oliver in Hammana Lebanon on the 11th of 1937 Gandhi used these words: " I have no message to give except this that there is no deliverance for any people on this earth or for all the people of this earth except through truth and nonviolence in every walk of life without any exceptions." 8 In this passage, Gandhi promises "deliverance" through nonviolence for oppressed peoples without exception. Speaking primarily with regards to nonviolence as a libratory philosophy in this passage, Gandhi emphasizes the power of nonviolence to emancipate spiritually and physically. It is a science and of its own can lead one to pure democracy. Satyagraha, the Centre of Gandhi's Contribution to the Philosophy of Nonviolence It will be good here to examine what Stanley E. Jones calls "the centre of Gandhi's contribution to the world". All else is marginal compared to it. Satyagraha is the quintessence of Gandhism. Through it, Gandhi introduced a new spirit to the world. It is the greatest of all Gandhi's contribution to the world. What is Satyagraha? Satyagraha (pronounced sat-YAH-graha) is a compound of two Sanskrit nouns satya, meaning truth (from 'sat'- 'being' with a suffix 'ya'), and agraha, meaning, "firm grasping" (a noun made from the agra, which has its root 'grah'- 'seize', 'grasp', with the verbal prefix 'a' – 'to' 'towards). Thus Satyagraha literally means devotion to truth, remaining firm on the truth and resisting untruth actively but nonviolently. Since the only way for Gandhi getting to the truth is by nonviolence (love), it follows that Satyagraha implies an unwavering search for the truth using nonviolence. Satyagraha according to Michael Nagler literally means 'clinging to truth,' and that was exactly how Gandhi understood it: "clinging to the truth that we are all one under the skin, that there is no such thing as a 'win/lose' confrontation because all our important interests are really the same, that consciously or not every single person wants unity and peace with every other" 9 Put succinctly, Satyagraha means 'truth force' , 'soul force' or as Martin Luther Jr would call it 'love in action.' Satyagraha has often been defined as the philosophy of nonviolent resistance most famously employed by Mahatma Gandhi, in forcing an end to the British domination. Gene Sharp did not hesitate to define Satyagraha simply as "Gandhian Nonviolence." 10 Today as Nagler would say, when we use the word Satyagraha we sometimes mean that general principle, the fact that love is stronger than hate (and we can learn to use it to overcome hate), and sometimes we mean more specifically active resistance by a repressed group; sometimes, even more specifically, we apply the term to a given movement like Salt Satyagraha etc. It is worthwhile looking at the way Gandhi uses Satyagraha. Gandhi View of Satyagraha Satyagraha was not a preconceived plan for Gandhi. Event in his life culminating in his "Bramacharya vow", 11 prepared him for it. He therefore underlined: Events were so shaping themselves in Johannesburg as to make this self-purification on my part a preliminary as it were to Satyagraha. I can now see that all the principal events of my life, culminating in the vow of Bramacharya were secretly preparing me for it. 12 Satyagraha is a moral weapon and the stress is on soul force over physical force. It aims at winning the enemy through love and patient suffering. It aims at winning over an unjust law, not at crushing, punishing, or taking revenge against the authority, but to convert and heal it. Though it started as a struggle for political rights, Satyagraha became in the long run a struggle for individual salvation, which could be achieved through love and self-sacrifice. Satyagraha is meant to overcome all methods of violence. Gandhi explained in a letter to Lord Hunter that Satyagraha is a movement based entirely upon truth. It replaces every form of violence, direct and indirect, veiled and unveiled and whether in thought, word or deed. Satyagraha is for the strong in spirit. A doubter or a timid person cannot do it. Satyagraha teaches the art of living well as well as dying. It is love and unshakeable firmness that comes from it. Its training is meant for all, irrespective of age and sex. The most important training is mental not physical. It has some basic precepts treated below. The Basic Precepts of Satyagraha There are three basic precepts essential to Satyagraha: Truth, Nonviolence and self-suffering. These are called the pillars of Satyagraha. Failure to grasp them is a handicap to the understanding of Gandhi's non –violence. These three fundamentals correspond to Sanskrit terms: Sat/Satya – Truth implying openness, honesty and fairness Ahimsa/Nonviolence – refusal to inflict injury upon others. Tapasya – willingness to self-sacrifice. These fundamental concepts are elaborated below. 1.Satya/Truth: Satyagraha as stated before literally means truth force. Truth is relative. Man is not capable of knowing the absolute truth. Satyagraha implies working steadily towards a discovery of the absolute truth and converting the opponent into a trend in the working process. What a person sees as truth may just as clearly be untrue for another. Gandhi made his life a numerous experiments with truth. In holding to the truth, he claims to be making a ceaseless effort to find it. Gandhi's conception of truth is deeply rooted in Hinduism. The emphasis of Satya-truth is paramount in the writings of the Indian philosophers. "Satyannasti Parodharmati (Satyan Nasti Paro Dharma Ti) – there is no religion or duty greater than truth", holds a prominent place in Hinduism. Reaching pure and absolute truth is attaining moksha. Gandhi holds that truth is God, and maintains that it is an integral part of Satyagraha. He explains it thus: The world rests upon the bedrock of satya or truth; asatya meaning untruth also means "nonexistent" and satya or truth, means that which is of untruth does not so much exist. Its victory is out of the question. And truth being "that which is" can never be destroyed. This is the doctrine of Satyagraha in a nutshell. 13 2.Ahimsa: In Gandhi's Satyagraha, truth is inseparable from Ahimsa. Ahimsa expresses as ancient Hindu, Jain and Buddhist ethical precept. The negative prefix 'a' plus himsa meaning injury make up the world normally translated 'nonviolence'. The term Ahimsa appears in Hindu teachings as early as the Chandoya Upanishad. The Jain Religion constitutes Ahimsa as the first vow. It is a cardinal virtue in Buddhism. Despite its being rooted in these Religions, the special contribution of Gandhi was: To make the concept of Ahimsa meaningful in the social and political spheres by moulding tools for nonviolent action to use as a positive force in the search for social and political truths. Gandhi formed Ahimsa into the active social technique, which was to challenge political authorities and religious orthodoxy. 14 It is worth noting that this 'active social technique which was to challenge political authorities', used by Gandhi is none other than Satyagraha. Truly enough, the Indian milieu was already infused with notions of Ahimsa. Nevertheless, Gandhi acknowledged that it was an essential part of his experiments with the truth whose technique of action he called Satyagraha. At the root of Satya and Ahimsa is love. While making discourses on the Bhagavad-Gita, an author says: Truth, peace, righteousness and nonviolence, Satya, Shanti, Dharma and Ahimsa, do not exist separately. They are all essentially dependent on love. When love enters the thoughts it becomes truth. When it manifests itself in the form of action it becomes truth. When Love manifests itself in the form of action it becomes Dharma or righteousness. When your feelings become saturated with love you become peace itself. The very meaning of the word peace is love. When you fill your understanding with love it is Ahimsa. Practicing love is Dharma, thinking of love is Satya, feeling love is Shanti, and understanding love is Ahimsa. For all these values it is love which flows as the undercurrent. 15 3.;Tapasya (Self-Suffering); it remains a truism that the classical yogic laws of self-restraint and self-discipline are familiar elements in Indian culture. Self-suffering in Satyagraha is a test of love. It is detected first of all towards the much persuasion of one whom is undertaken. Gandhi distinguished self-suffering from cowardice. Gandhi's choice of self-suffering does not mean that he valued life low. It is rather a sign of voluntary help and it is noble and morally enriching. He himself says; It is not because I value life lo I can countenance with joy Thousands voluntary losing their lives for Satyagraha, but because I know that it results in the long run in the least loss of life, and what is more, it ennobles those who lose their lives and morally enriches the world for their sacrifice. 16 Satyagraha is at its best when preached and practiced by those who would use arms but decided instead to invite suffering upon them. It is not easy for a western mind or nonoriental philosopher to understand this issue of self-suffering. In fact, in Satyagraha, the element of self-suffering is perhaps the least acceptable to a western mind. Yet such sacrifice may well provide the ultimate means of realizing that characteristic so eminent in Christian religion and western moral philosophy: The dignity of the individual. The three elements: Satya, Ahimsa, Tapasya must move together for the success of any Satyagraha campaign. It follows that Ahimsa – which implies love, leads in turn to social service. Truth leads to an ethical humanism. Self-suffering not for its own sake, but for the demonstration of sincerity flowing from refusal to injure the opponent while at the same time holding to the truth, implies sacrifice and preparation for sacrifice even to death. Satyagraha in Action For Satyagraha to be valid, it has to be tested. When the principles are applied to specific political and social action, the tools of civil disobedience, noncooperation, nonviolent strike, and constructive action are cherished. South Africa and India were 'laboratories' where Gandhi tested his new technique. Satyagraha was a necessary weapon for Gandhi to work in South Africa and India. Louis Fischer attests that: "Gandhi could never have achieved what he did in South Africa and India but for a weapon peculiarly his own. It was unprecedented indeed; it was so unique he could not find a name for it until he finally hit upon Satyagraha." 17 South Africa is the acclaimed birthplace of Satyagraha. Here Satyagraha was employed to fight for the civil rights of Indians in South Africa. In India, Gandhi applied Satyagraha in his socio-political milieu and carried out several acts of civil disobedience culminating in the Salt March. Another wonderful way of seeing Satyagraha in action is through the fasting of Mahatma Gandhi. Fasting was part and parcel of his philosophy of truth and nonviolence. Mahatma Gandhi was an activist – a moral and spiritual activist. And fasting was "one of his strategies of activism, in many ways his most powerful." 18 Qualities of a Satyagrahi (Nonviolence Activist) Gandhi was quite aware that there was need to train people who could carry on with his Satyagraha campaigns. He trained them in his "Satyagraha Ashrams". Here are some of the basic qualities of expected of a Satyagrahi. A Satyagraha should have a living faith in God for he is his only Rock. One must believe in truth and nonviolence as one's creed and therefore have faith in the inherent goodness of human nature. One must live a chaste life and be ready and willing for the sake of one's cause to give up his life and his possessions. One must be free from the use any intoxicant, in order that his reason may be undivided and his mind constant. One must carry out with a willing heart all the rules of discipline as may be laid down from time to time. One should carry out the jail rules unless they are especially dense to hurt his self-respect. A satyagrahi must accept to suffer in order to correct a situation. In a nutshell, Satyagraha is itself a movement intended to fight social and promote ethical values. It is a whole philosophy of nonviolence. It is undertaken only after all the other peaceful means have proven ineffective. At its heart is nonviolence. An attempt is made to convert, persuade or win over the opponent. It involves applying the forces of both reason and conscience simultaneously, while holding aloft the indisputable truth of his/her position. The Satyagrahi also engages in acts of voluntary suffering. Any violence inflicted by the opponent is accepted without retaliation. The opponent can only become morally bankrupt if violence continues to be inflicted indefinitely. Several methods can be applied in a Satyagraha campaign. Stephen Murphy gives primacy to "noncooperation and fasting". Bertrand Russell has this to say about Gandhi's method: The essence of this method which he (Gandhi) gradually brought to greater and greater perfection consisted in refusal to do things, which the authorities wished to have done, while abstaining from any positive action of an aggressive sort.... The method always had in Gandhi's mind a religious aspect... As a rule, this method depended upon moral force for its success. 19 Murphy and Russell do not accept Gandhi's doctrine totally. Michael Nagler insists that they ignore Constructive Programme, which Gandhi considered paramount. A better understanding of Gandhi's nonviolence will be seen in the next chapter.

- M. SHEPARD, Mahatma Gandhi and his Myths, Civil Disobedience, Nonviolence and Satyagraha in the Real World, Los Angeles,

- Shepard Publications, 2002, http://www.markshep.com/nonviolence/books/myths.html

- M. K. GANDHI, All Men Are Brothers, Autobiographical Reflections, Krishna Kripalani (ed.), New York; The Continuum Publishing Company, 1990, vii.

- M. K. GANDHI, Young India, 22-11-1928, The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. xxxviii, Ahmedabad; Navajivan Trust, 1970, 69.

- M. K. GANDHI, Young India, 20-12-1928, in ibidem, 247.

- The New Zion’s Herald, July/August 2001, vol. 175, issue 4, 17.

- M. K. GANDHI, An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments With truth, Ahmedabad; Navajivan Trust, 2003, 254.

- NIRMAL KUMAR BOSE, Selections from Gandhi, Ahmedabad; Navajivan Trust, 1948,154.

- Mahatma Gandhi, Judith M. Brown, The Essential Writings, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008, 20. Also in Pyarelal Papers, EWMG, 60.

- Michael N. Nagler, Hope or Terror? Minneapolis, METTA Center for Nonviolence Education, 2009, p. 7.

- T. WEBER and R. J. Burrowes, Nonviolence, An Introduction, http://www.nonviolenceinternational.net/seasia

- Bramacharya Simply means Celibacy, Chastity.

- M. K. GANDHI, An Autobiography, 292.

- S. E. JONES, Gandhi, Portrayal of a Friend, Nashville, Abingdon Press, 1948, 82.

- J. V. BONDURANT, Conquest of Violence, The Gandhian Philosophy of Conflict. Los Angeles; University of California Press, 1965, 112.

- BHAGAVAN SRI SATHYA SAI BABA, Discourses on the Bhagavad-Gita, Andhra Pradesh; Sri Sathya Sai Books and Publications Trust, 1988, 51-52.

- M. K. GANDHI, Nonviolence in Peace and War,(2nd ed.) Ahmedadad, Navijivan Trust, 1944, 49.

- L. FISCHER. Gandhi; His life and Message For the World, New York Mentor Books, 1954, 35.

- S. E. JONES, Gandhi, Portrayal of a Friend, 108.

- B. RUSSELL, Mahatma Gandhi, Boston, Atlantic Monthly, December 1952, 23.

Remembering Gandhi Assassination of Gandhi Tributes to Gandhi Gandhi's Human Touch Gandhi Poster Exhibition Send Gandhi Greetings Gandhi Books Read Gandhi Books Online Download PDF Books Download EPUB/MOBI Books Gandhi Literature Collected Works of M. Gandhi Selected Works of M.Gandhi Selected Letters Famous Speeches Gandhi Resources Gandhi Centres/Institutions Museums/Ashrams/Libraries Gandhi Tourist Places Resource Persons Related Websites Glossary / Sources Associates of Mahatma Gandhi -->

Copyright © 2015 SEVAGRAM ASHRAM. All rights reserved. Developed and maintain by Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal | Sitemap

Essay on Mahatma Gandhi [100, 150, 200, 300, 500 Words]

Essay on Mahatma Gandhi in English: In this article, you are going to read short and long essays on Mahatma Gandhi in English (100, 150, 200-250, 300, and 500 words). This article will be also helpful for you If you are looking for a speech on Mahatma Gandhi or Paragraph on Mahatma Gandhi in English. We’ve written this article for students of all classes (nursery to class 12). So, let’s get started.

Table of Contents

Short Essay on Mahatma Gandhi 100 Words

Mahatma Gandhi was one of the greatest leaders of our country. He was born in Porbandar, India, on October 2, 1869. His father Karamchand Gandhi was the Dewan and his mother Putlibai was a pious lady. Gandhiji went to England to become a barrister. In 1893 he went to South Africa and worked for the rights of our people.

He returned to India in 1915 and joined the freedom struggle. He started many political movements like Non-cooperation movement, Salt Satyagraha, Quit India Movement to fight against the British. Gandhiji worked for the ending of the caste system and the establishment of Hindu-Muslim unity. He was killed by Nathuram Godse On January 30, 1948.

Mahatma Gandhi Essay in English 150 Words

Mahatma Gandhi was a great leader. His full name was Mohandas and Gandhi. He was born on October 2, 1869 at Porbandar. His father was a Diwan. He was an average student. He went to England and returned as a barrister.

In South Africa, Gandhiji saw the bad condition of the Indians. There he raised his voice against it and organised a movement.

In India, he started the non-cooperation and Satyagraha movements to fight against the British Government. He went to jail many times. He wanted Hindu-Muslim unity. In 1947, he got freedom for us.

Gandhiji was a great social reformer. He worked for Dalits and lower-class people. He lived a very simple life. He wanted peace. He believed in Ahimsa.

On January 30, 1948, he was shot dead. We call him ‘Bapu’ out of love and respect. He is the Father of the Nation.

Also Read: 10 Lines on Mahatma Gandhi

Essay on Mahatma Gandhi 200-250 Words

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi was an Indian lawyer, freedom activist, and politician. Gandhiji was born on October 2, 1869 at Porbandar, Gujarat. His father Karamchand Gandhi was the Chief Minister (diwan) of Porbandar state. His mother Putlibai was a religious woman.

He went to England to study law at the age of 18 years. After his return to India, he started a practice as a lawyer in the Bombay High Court. He went to South Africa and started practicing law. There he protested against the injustice and harsh treatment of the white people towards the native Africans and Indians.

He returned to India in 1915 and started to take interest in politics. Mahatma Gandhi used the ideals of truth and non-violence as weapons to fight against British colonial rule. He worked for the upliftment of Harijans. He fought against untouchability and worked for Hindu-Muslim unity.

Through his freedom movements like Non-cooperation movement, Khilafat movement, and civil disobedience movement he fought for freedom against the British imperialists. 1942, he launched the Quit India movement to end the British rule. At last, India got freedom in 1947 at his initiative.

People affectionately call him ‘Bapu’ and the ‘Father of the Nation’. He was shot dead in 1948 by the Hindu fanatic Nathuram Godse. Gandhiji’s life is a true inspiration for all of us.

Mahatma Gandhi Essay in English 300 Words

Mahatma Gandhi was born at Porbandar in Gujarat on 2nd October, 1869. His father was the Diwan of the State. His name was Karam Chand Gandhi. Mahatma Gandhi’s full name was Mohan Das Karamchand Gandhi. His mother’s name was Putali Bai. Mahatma Gandhi went to school first at Porbandar then at Rajkot. Even as a child, Mahatma never told a lie. He passed his Matric examination at the age of 18.

Mohan Das was married to Kasturba at the age of thirteen. Mahatma Gandhi was sent to England to study law and became a Barrister. He lived a very simple life even in England. After getting his law degree, he returned to India.

Mr. Gandhi started his law practice. He went to South Africa in the course of a law suit. He saw the condition of the Indians living there. They were treated very badly by the white men. They were not allowed to travel in 1st class on the trains, also not allowed to enter certain localities, clubs, and so on. Once when Gandhiji was travelling in the 1st class compartment of the train, he was beaten and thrown out of the train. Then Mahatma decided to unite all Indians and started the Non-violence and Satyagrah Movement. In no time, the Movement picked up.

Mahatma Gandhi returned to India and joined Indian National Congress. He started the Non-violence, Non-cooperation Movements here also. He travelled all over India, especially the rural India to see the conditions of the poor.

Mahatma Gandhi started Satyagrah Movement to oppose the Rowlatt Act and there was the shoot-out at Jalian-Wala-Bagh. The Act was drawn after many people were killed. He then started the Salt Satyagraha and Quit India Movements. And finally, Gandhiji won freedom for us. India became free on 15th August, 1947. He is called as “Father of the Nation”. Unfortunately, Gandhiji was shot on 30 January 1948 by a Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse.

Also Read: Gandhi Jayanti Speech 10 Lines

Mahatma Gandhi Essay in English 500 Words

Introduction:.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi was a politician, social activist, writer, and leader of the Indian national movement. He is a figure known all over the world. His name is a household word in India, rather, in all the world round. His creed of non-violence has placed him on the same par with Buddha, Sri Chaitanya, and Jesus Christ.

Family & Education:

Mahatma Gandhi was born in the small town of Porbandar in the Kathiwad state on October 2, 1869. His father Karamchand Gandhi was the prime minister of Rajkot State and his mother Putlibai was a pious lady. Her influence shaped the future life of Mahatma Gandhi.

He was sent to school at a very early age, but he was not a very bright student. After his Matriculation Examination, he went to England to study law and returned home as a barrister. He began to practice law in Bombay but he was not very successful.

Life in South Africa:

In 1893 Gandhiji went to South Africa in connection with a case. He found his own countrymen treated with contempt by the whites. Gandhiji started satyagraha against this color hated. It was a non-violent protest, yet hundreds were beaten up and thousands were sent to jail. But Gandhiji did not buzz an inch from his faith in truth and non-violence and at last, he succeeded in his mission. He was awarded the title of Mahatma.

Fight for India’s Independence:

In 1915 Gandhiji came back to India after twenty long years in South Africa. He joined the Indian National congress and championed the cause of India’s freedom movement. He asked people to unite for the cause of freedom. He used the weapons of truth and non-violence to fight against the mighty British.

The horrible massacre at Jalianwalabag in Punjab touched him and he resolved to face the brute force of the British Government with moral force. In 1920 he launched the Non-cooperation movement to oppose British rule in India.

He led the famous Dandi March on 12th March 1930. This march was meant to break the salt law. And as a result of this, the British rule in India had already started shaking and he had to go to London for a Round Table Conference in 1931. But this Conference proved abortive and the country was about to give a death blow to the foreign rule.

In 1942 Gandhiji launched his final bout for freedom. He started the ‘Quit India’ movement. At last, the British Government had to quit India in 1947, and India was declared a free country on August 15, 1947.

Social Works:

Mahatma Gandhi was a social activist who fought against the evils of society. He found the Satyagraha Ashram on the banks of the Sabarmati river in Gujarat. He preached against untouchability and worked for Hindu-Muslim unity. He fought tirelessly for the rights of Harijans.

Conclusion:

Mahatma Gandhi, the father of the nation was a generous, god-loving, and peace-loving person. But unfortunately, he was assassinated by Nathuram Godse on 30th January 1948 at the age of 78. To commemorate Gandhiji’s birth anniversary Gandhi Jayanti is celebrated every year on October 2. Gandhiji’s teachings and ideologies will continue to enlighten and encourage us in the future.

Read More: 1. Essay on Swami Vivekananda 2. Essay on Subhash Chandra Bose 3. Essay on Mother Teresa 4. Essay on APJ Abdul Kalam 5. Essay on Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

Related Posts

Apj abdul kalam essay in english | 100, 200, 300, 500 words, blood donation essay in english | 150, 200, 300 words, my mother essay in english 10 lines [5 sets], essay on mother teresa in english for students [300 words], leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

https://studynlearn.com/

Essay on mahatma gandhi: biography of mahatma gandhi | 800+ words.

Mahatma Gandhi, one of the most influential figures of the 20th century, is widely regarded as the Father of the Nation in India. He was a freedom fighter, political leader, and spiritual teacher who dedicated his life to nonviolent resistance and social justice. In this essay on Mahatma Gandhi biography in English, we will explore his life, legacy, and achievements. From his humble beginnings in Porbandar, Gujarat, to his leadership in India's independence movement, Gandhi's teachings and philosophy have had a profound impact on social and political movements around the world. This essay will delve into his life's work and highlight the enduring legacy of this remarkable individual.

In this article, we have shared 800+ words essay on mahatama gandhi, including all the birth, childhood, marriage and education of Mahatma Gandhi.

Essay On Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi is also known as Mahatma Gandhi is considered to be the father of this country. In the fight for independence against British rule, he was the leader of the nationalist movement. He was an Indian lawyer, political ethicist, anti-colonial nationalist, writer, and a kind-hearted person.

Birth and Childhood

Mahatma Gandhi was born on October 2, the year 1869 in a place named Porbandar, Gujrat in northwest India. He was born in a Hindu Modh family. His father Karamchand Gandhi was a political figure and also the chief minister of Porbandar. His mother named Putlibai Gandhi was the fourth wife of his father, previous wives died during childbirth. Gandhi was born in a vaishya family that's why from an early age of life he learned a lot of things such as non-injury to living beings, tolerance and vegetarianism.

In May 1883, he was 13 years old when he got married to a girl named Kasturba Makhanji, who was also 13 years old, this marriage was arranged by their parents. They together had four sons, Harilal (1888), Manilal (1892), Ramdas (1897), Devdas (1900).

In this essay on Mahatma Gandhi, let's know about Mahatma Gandhi's education Porbandar did not have enough chance of education, all the children in school used to write in dust with their fingers. However, he was lucky that his father became the chief minister of another city named Rajkot. He was average in education. At the age of 13, he lost a year at school due to marriage. He was not a shining student in the classroom or playground, but he always obeyed the given order by elders.

That's why like other kids he did not go through all the teenage life. He wanted to eat meat but never did because of their parent's beliefs. In the year of 1887, Gandhi passed the matriculation examination from the University of Bombay and joined a college in Bhavnagar named Samaldas College. It was clear for him by then that if he has to maintain his family tradition and become a high office working person in the state of Gujarat, he would have to become a barrister.

At the age of 18, he was offered to continue his studies in London and he was not very happy at Samaldas College so he accepted the offer and sailed to London in September 1888. After reaching London, He was having difficulty understanding the culture and understanding the English language. Some days after arrival he joined a Law college named Inner Temple which was one of the four London law colleges.

The transformation of changing life from a city to India studying in a college in England was not easy for him but he took his study very seriously and started to brush up his English and Latin. His vegetarianism became a very problematic subject for him as everyone around him as eating meat and he started to feel embarrassed.

Some of his new friends in London said some of the things like not eating meat will make him weak physically and mentally. But eventually, he found a vegetarian restaurant and a book that helped him understand the reason to become a vegetarian. From childhood, he wanted to eat meat himself but never did because of his parents but now in London, he was convinced that he finally embraced vegetarianism and never again thought of eating meat.

After some time he became an active member of the society called London vegetarian society and started to attend all the conferences and journals. In England not only Gandhi met Food faddists but also met some men and women who had vast knowledge about Bhagavad-Gita, Bible, Mahabharata, etc. From them, he learned a lot about Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity and many others.

Many people he met were rebels not supporting the Victorian establishment from these people Gandhi slowly absorbed politics, personality, and more importantly ideas. He passed his study from England and became a Barrister but there was some painful news was waiting for him back at home in India. In January 1891 Gandhi's mother died while Gandhi was still in London.

He came back to India in July 1891 and started to begin the legal career but he lost his very first case in India. He soon realized that the legal profession was heavily overcrowded and he changed his path. He then was offered to be a teacher in Bombay high school but he turned it down and returned to Rajkot. With the dream of living a good life, he started to draft petitions for litigants which soon ended with the dissatisfaction of a local British officer.

Fortunately in the year 1893, he got an offer to go to Natal, South Africa and work there in an Indian firm for 1 year as it was a contract basis.

Civil Right Movement in Africa

South Africa was waiting with a lot of challenges and opportunities for him. From there he started to grow a new leaf. In South Africa 2 of his four sons were born. He had to face many difficulties there too. Once he as advocating for his client and he had to flee from the court because he was so nervous, he wasn't able to talk properly. But the bigger problem was waiting for him, as he had to face racial discrimination in South Africa.

In the journey from Durban to Pretoria, he faced a lot from, being asked to take off the turban in a court to travel on a car footboard to make room for European passenger but he refused. He was beaten by a taxi driver and thrown out of a first-class compartment but these instances made him strong and gave him the strength to fight for justice.

He started to educate others about their rights and duties. When he learned about a bill to deprive Indians of the right to vote, it was that time when others begged him to take up the fight on behalf of them. Eventually at the age of 25 in July 1894 he became a proficient political campaigner.

He drafted petitions and got them signed by hundreds of compatriots. He was not able to stop the bill but succeeded in drawing the attention of the public in Natal, England, and India. He then built many societies in Durban. He planted the seed, spirit of solidarity in the Indian community.