Search form

- About Faculty Development and Support

- Programs and Funding Opportunities

Consultations, Observations, and Services

- Strategic Resources & Digital Publications

- Canvas @ Yale Support

- Learning Environments @ Yale

- Teaching Workshops

- Teaching Consultations and Classroom Observations

- Teaching Programs

- Spring Teaching Forum

- Written and Oral Communication Workshops and Panels

- Writing Resources & Tutorials

- About the Graduate Writing Laboratory

- Writing and Public Speaking Consultations

- Writing Workshops and Panels

- Writing Peer-Review Groups

- Writing Retreats and All Writes

- Online Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- About Teaching Development for Graduate and Professional School Students

- Teaching Programs and Grants

- Teaching Forums

- Resources for Graduate Student Teachers

- About Undergraduate Writing and Tutoring

- Academic Strategies Program

- The Writing Center

- STEM Tutoring & Programs

- Humanities & Social Sciences

- Center for Language Study

- Online Course Catalog

- Antiracist Pedagogy

- NECQL 2019: NorthEast Consortium for Quantitative Literacy XXII Meeting

- STEMinar Series

- Teaching in Context: Troubling Times

- Helmsley Postdoctoral Teaching Scholars

- Pedagogical Partners

- Instructional Materials

- Evaluation & Research

- STEM Education Job Opportunities

- Yale Connect

- Online Education Legal Statements

You are here

Case-based learning.

Case-based learning (CBL) is an established approach used across disciplines where students apply their knowledge to real-world scenarios, promoting higher levels of cognition (see Bloom’s Taxonomy ). In CBL classrooms, students typically work in groups on case studies, stories involving one or more characters and/or scenarios. The cases present a disciplinary problem or problems for which students devise solutions under the guidance of the instructor. CBL has a strong history of successful implementation in medical, law, and business schools, and is increasingly used within undergraduate education, particularly within pre-professional majors and the sciences (Herreid, 1994). This method involves guided inquiry and is grounded in constructivism whereby students form new meanings by interacting with their knowledge and the environment (Lee, 2012).

There are a number of benefits to using CBL in the classroom. In a review of the literature, Williams (2005) describes how CBL: utilizes collaborative learning, facilitates the integration of learning, develops students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to learn, encourages learner self-reflection and critical reflection, allows for scientific inquiry, integrates knowledge and practice, and supports the development of a variety of learning skills.

CBL has several defining characteristics, including versatility, storytelling power, and efficient self-guided learning. In a systematic analysis of 104 articles in health professions education, CBL was found to be utilized in courses with less than 50 to over 1000 students (Thistlethwaite et al., 2012). In these classrooms, group sizes ranged from 1 to 30, with most consisting of 2 to 15 students. Instructors varied in the proportion of time they implemented CBL in the classroom, ranging from one case spanning two hours of classroom time, to year-long case-based courses. These findings demonstrate that instructors use CBL in a variety of ways in their classrooms.

The stories that comprise the framework of case studies are also a key component to CBL’s effectiveness. Jonassen and Hernandez-Serrano (2002, p.66) describe how storytelling:

Is a method of negotiating and renegotiating meanings that allows us to enter into other’s realms of meaning through messages they utter in their stories,

Helps us find our place in a culture,

Allows us to explicate and to interpret, and

Facilitates the attainment of vicarious experience by helping us to distinguish the positive models to emulate from the negative model.

Neurochemically, listening to stories can activate oxytocin, a hormone that increases one’s sensitivity to social cues, resulting in more empathy, generosity, compassion and trustworthiness (Zak, 2013; Kosfeld et al., 2005). The stories within case studies serve as a means by which learners form new understandings through characters and/or scenarios.

CBL is often described in conjunction or in comparison with problem-based learning (PBL). While the lines are often confusingly blurred within the literature, in the most conservative of definitions, the features distinguishing the two approaches include that PBL involves open rather than guided inquiry, is less structured, and the instructor plays a more passive role. In PBL multiple solutions to the problem may exit, but the problem is often initially not well-defined. PBL also has a stronger emphasis on developing self-directed learning. The choice between implementing CBL versus PBL is highly dependent on the goals and context of the instruction. For example, in a comparison of PBL and CBL approaches during a curricular shift at two medical schools, students and faculty preferred CBL to PBL (Srinivasan et al., 2007). Students perceived CBL to be a more efficient process and more clinically applicable. However, in another context, PBL might be the favored approach.

In a review of the effectiveness of CBL in health profession education, Thistlethwaite et al. (2012), found several benefits:

Students enjoyed the method and thought it enhanced their learning,

Instructors liked how CBL engaged students in learning,

CBL seemed to facilitate small group learning, but the authors could not distinguish between whether it was the case itself or the small group learning that occurred as facilitated by the case.

Other studies have also reported on the effectiveness of CBL in achieving learning outcomes (Bonney, 2015; Breslin, 2008; Herreid, 2013; Krain, 2016). These findings suggest that CBL is a vehicle of engagement for instruction, and facilitates an environment whereby students can construct knowledge.

Science – Students are given a scenario to which they apply their basic science knowledge and problem-solving skills to help them solve the case. One example within the biological sciences is two brothers who have a family history of a genetic illness. They each have mutations within a particular sequence in their DNA. Students work through the case and draw conclusions about the biological impacts of these mutations using basic science. Sample cases: You are Not the Mother of Your Children ; Organic Chemisty and Your Cellphone: Organic Light-Emitting Diodes ; A Light on Physics: F-Number and Exposure Time

Medicine – Medical or pre-health students read about a patient presenting with specific symptoms. Students decide which questions are important to ask the patient in their medical history, how long they have experienced such symptoms, etc. The case unfolds and students use clinical reasoning, propose relevant tests, develop a differential diagnoses and a plan of treatment. Sample cases: The Case of the Crying Baby: Surgical vs. Medical Management ; The Plan: Ethics and Physician Assisted Suicide ; The Haemophilus Vaccine: A Victory for Immunologic Engineering

Public Health – A case study describes a pandemic of a deadly infectious disease. Students work through the case to identify Patient Zero, the person who was the first to spread the disease, and how that individual became infected. Sample cases: The Protective Parent ; The Elusive Tuberculosis Case: The CDC and Andrew Speaker ; Credible Voice: WHO-Beijing and the SARS Crisis

Law – A case study presents a legal dilemma for which students use problem solving to decide the best way to advise and defend a client. Students are presented information that changes during the case. Sample cases: Mortgage Crisis Call (abstract) ; The Case of the Unpaid Interns (abstract) ; Police-Community Dialogue (abstract)

Business – Students work on a case study that presents the history of a business success or failure. They apply business principles learned in the classroom and assess why the venture was successful or not. Sample cases: SELCO-Determining a path forward ; Project Masiluleke: Texting and Testing to Fight HIV/AIDS in South Africa ; Mayo Clinic: Design Thinking in Healthcare

Humanities - Students consider a case that presents a theater facing financial and management difficulties. They apply business and theater principles learned in the classroom to the case, working together to create solutions for the theater. Sample cases: David Geffen School of Drama

Recommendations

Finding and Writing Cases

Consider utilizing or adapting open access cases - The availability of open resources and databases containing cases that instructors can download makes this approach even more accessible in the classroom. Two examples of open databases are the Case Center on Public Leadership and Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Case Program , which focus on government, leadership and public policy case studies.

- Consider writing original cases - In the event that an instructor is unable to find open access cases relevant to their course learning objectives, they may choose to write their own. See the following resources on case writing: Cooking with Betty Crocker: A Recipe for Case Writing ; The Way of Flesch: The Art of Writing Readable Cases ; Twixt Fact and Fiction: A Case Writer’s Dilemma ; And All That Jazz: An Essay Extolling the Virtues of Writing Case Teaching Notes .

Implementing Cases

Take baby steps if new to CBL - While entire courses and curricula may involve case-based learning, instructors who desire to implement on a smaller-scale can integrate a single case into their class, and increase the number of cases utilized over time as desired.

Use cases in classes that are small, medium or large - Cases can be scaled to any course size. In large classes with stadium seating, students can work with peers nearby, while in small classes with more flexible seating arrangements, teams can move their chairs closer together. CBL can introduce more noise (and energy) in the classroom to which an instructor often quickly becomes accustomed. Further, students can be asked to work on cases outside of class, and wrap up discussion during the next class meeting.

Encourage collaborative work - Cases present an opportunity for students to work together to solve cases which the historical literature supports as beneficial to student learning (Bruffee, 1993). Allow students to work in groups to answer case questions.

Form diverse teams as feasible - When students work within diverse teams they can be exposed to a variety of perspectives that can help them solve the case. Depending on the context of the course, priorities, and the background information gathered about the students enrolled in the class, instructors may choose to organize student groups to allow for diversity in factors such as current course grades, gender, race/ethnicity, personality, among other items.

Use stable teams as appropriate - If CBL is a large component of the course, a research-supported practice is to keep teams together long enough to go through the stages of group development: forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning (Tuckman, 1965).

Walk around to guide groups - In CBL instructors serve as facilitators of student learning. Walking around allows the instructor to monitor student progress as well as identify and support any groups that may be struggling. Teaching assistants can also play a valuable role in supporting groups.

Interrupt strategically - Only every so often, for conversation in large group discussion of the case, especially when students appear confused on key concepts. An effective practice to help students meet case learning goals is to guide them as a whole group when the class is ready. This may include selecting a few student groups to present answers to discussion questions to the entire class, asking the class a question relevant to the case using polling software, and/or performing a mini-lesson on an area that appears to be confusing among students.

Assess student learning in multiple ways - Students can be assessed informally by asking groups to report back answers to various case questions. This practice also helps students stay on task, and keeps them accountable. Cases can also be included on exams using related scenarios where students are asked to apply their knowledge.

Barrows HS. (1996). Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: a brief overview. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 68, 3-12.

Bonney KM. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains. Journal of Microbiology and Biology Education, 16(1): 21-28.

Breslin M, Buchanan, R. (2008) On the Case Study Method of Research and Teaching in Design. Design Issues, 24(1), 36-40.

Bruffee KS. (1993). Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and authority of knowledge. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Herreid CF. (2013). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science, edited by Clyde Freeman Herreid. Originally published in 2006 by the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA); reprinted by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) in 2013.

Herreid CH. (1994). Case studies in science: A novel method of science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 23(4), 221–229.

Jonassen DH and Hernandez-Serrano J. (2002). Case-based reasoning and instructional design: Using stories to support problem solving. Educational Technology, Research and Development, 50(2), 65-77.

Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435, 673-676.

Krain M. (2016) Putting the learning in case learning? The effects of case-based approaches on student knowledge, attitudes, and engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 27(2), 131-153.

Lee V. (2012). What is Inquiry-Guided Learning? New Directions for Learning, 129:5-14.

Nkhoma M, Sriratanaviriyakul N. (2017). Using case method to enrich students’ learning outcomes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 18(1):37-50.

Srinivasan et al. (2007). Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: Effects of a major curricular shift at two institutions. Academic Medicine, 82(1): 74-82.

Thistlethwaite JE et al. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 23. Medical Teacher, 34, e421-e444.

Tuckman B. (1965). Development sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384-99.

Williams B. (2005). Case-based learning - a review of the literature: is there scope for this educational paradigm in prehospital education? Emerg Med, 22, 577-581.

Zak, PJ (2013). How Stories Change the Brain. Retrieved from: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning routinely supports members of the Yale community with individual instructional consultations and classroom observations.

Instructional Enhancement Fund

The Instructional Enhancement Fund (IEF) awards grants of up to $500 to support the timely integration of new learning activities into an existing undergraduate or graduate course. All Yale instructors of record, including tenured and tenure-track faculty, clinical instructional faculty, lecturers, lectors, and part-time acting instructors (PTAIs), are eligible to apply. Award decisions are typically provided within two weeks to help instructors implement ideas for the current semester.

Reserve a Room

The Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning partners with departments and groups on-campus throughout the year to share its space. Please review the reservation form and submit a request.

- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

Center for Teaching

Case studies.

Print Version

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites:

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy , University of Washington

For more information:

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

Book Review : Teaching and the Case Method , 3rd ed., vols. 1 and 2, by Louis Barnes, C. Roland (Chris) Christensen, and Abby Hansen. Harvard Business School Press, 1994; 333 pp. (vol 1), 412 pp. (vol 2).

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

View videos, articles, presentations, research papers, and other resources of interest to STEM Teacher Leaders.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science

- Case Studies

This website provides access to an award-winning collection of peer-reviewed case studies. The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science also offers a five-day summer workshop and a two-day fall conference to train faculty in the case method of teaching science. In addition, they are actively engaged in educational research to assess the impact of the case method on student learning.

Case Studies in Science Education

A video library for k-8 science teachers: 25 half-hour video programs and guides.

These video case studies take science education reform to a personal level, where individual teachers struggle to make changes that matter. Follow Donna, Mike, Audrey, and other science teachers as they work to adopt one or more research-based interventions to improve science teaching and learning. Each case follows a single teacher over the course of a year and is divided into three modules: the teacher's background and the problem he or she chooses to address, the chosen approach and implementation, and the outcome with assessment by the teacher and his or her advisor. Average running time: 1/2 hour. Program guides and supporting materials (PDF) Program guides and supporting materials (Link)

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Case Method Teaching and Learning

What is the case method? How can the case method be used to engage learners? What are some strategies for getting started? This guide helps instructors answer these questions by providing an overview of the case method while highlighting learner-centered and digitally-enhanced approaches to teaching with the case method. The guide also offers tips to instructors as they get started with the case method and additional references and resources.

On this page:

What is case method teaching.

- Case Method at Columbia

Why use the Case Method?

Case method teaching approaches, how do i get started.

- Additional Resources

The CTL is here to help!

For support with implementing a case method approach in your course, email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2019). Case Method Teaching and Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved from [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/case-method/

Case method 1 teaching is an active form of instruction that focuses on a case and involves students learning by doing 2 3 . Cases are real or invented stories 4 that include “an educational message” or recount events, problems, dilemmas, theoretical or conceptual issue that requires analysis and/or decision-making.

Case-based teaching simulates real world situations and asks students to actively grapple with complex problems 5 6 This method of instruction is used across disciplines to promote learning, and is common in law, business, medicine, among other fields. See Table 1 below for a few types of cases and the learning they promote.

Table 1: Types of cases and the learning they promote.

For a more complete list, see Case Types & Teaching Methods: A Classification Scheme from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

Back to Top

Case Method Teaching and Learning at Columbia

The case method is actively used in classrooms across Columbia, at the Morningside campus in the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), the School of Business, Arts and Sciences, among others, and at Columbia University Irving Medical campus.

Faculty Spotlight:

Professor Mary Ann Price on Using Case Study Method to Place Pre-Med Students in Real-Life Scenarios

Read more

Professor De Pinho on Using the Case Method in the Mailman Core

Case method teaching has been found to improve student learning, to increase students’ perception of learning gains, and to meet learning objectives 8 9 . Faculty have noted the instructional benefits of cases including greater student engagement in their learning 10 , deeper student understanding of concepts, stronger critical thinking skills, and an ability to make connections across content areas and view an issue from multiple perspectives 11 .

Through case-based learning, students are the ones asking questions about the case, doing the problem-solving, interacting with and learning from their peers, “unpacking” the case, analyzing the case, and summarizing the case. They learn how to work with limited information and ambiguity, think in professional or disciplinary ways, and ask themselves “what would I do if I were in this specific situation?”

The case method bridges theory to practice, and promotes the development of skills including: communication, active listening, critical thinking, decision-making, and metacognitive skills 12 , as students apply course content knowledge, reflect on what they know and their approach to analyzing, and make sense of a case.

Though the case method has historical roots as an instructor-centered approach that uses the Socratic dialogue and cold-calling, it is possible to take a more learner-centered approach in which students take on roles and tasks traditionally left to the instructor.

Cases are often used as “vehicles for classroom discussion” 13 . Students should be encouraged to take ownership of their learning from a case. Discussion-based approaches engage students in thinking and communicating about a case. Instructors can set up a case activity in which students are the ones doing the work of “asking questions, summarizing content, generating hypotheses, proposing theories, or offering critical analyses” 14 .

The role of the instructor is to share a case or ask students to share or create a case to use in class, set expectations, provide instructions, and assign students roles in the discussion. Student roles in a case discussion can include:

- discussion “starters” get the conversation started with a question or posing the questions that their peers came up with;

- facilitators listen actively, validate the contributions of peers, ask follow-up questions, draw connections, refocus the conversation as needed;

- recorders take-notes of the main points of the discussion, record on the board, upload to CourseWorks, or type and project on the screen; and

- discussion “wrappers” lead a summary of the main points of the discussion.

Prior to the case discussion, instructors can model case analysis and the types of questions students should ask, co-create discussion guidelines with students, and ask for students to submit discussion questions. During the discussion, the instructor can keep time, intervene as necessary (however the students should be doing the talking), and pause the discussion for a debrief and to ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the case activity.

Note: case discussions can be enhanced using technology. Live discussions can occur via video-conferencing (e.g., using Zoom ) or asynchronous discussions can occur using the Discussions tool in CourseWorks (Canvas) .

Table 2 includes a few interactive case method approaches. Regardless of the approach selected, it is important to create a learning environment in which students feel comfortable participating in a case activity and learning from one another. See below for tips on supporting student in how to learn from a case in the “getting started” section and how to create a supportive learning environment in the Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia .

Table 2. Strategies for Engaging Students in Case-Based Learning

Approaches to case teaching should be informed by course learning objectives, and can be adapted for small, large, hybrid, and online classes. Instructional technology can be used in various ways to deliver, facilitate, and assess the case method. For instance, an online module can be created in CourseWorks (Canvas) to structure the delivery of the case, allow students to work at their own pace, engage all learners, even those reluctant to speak up in class, and assess understanding of a case and student learning. Modules can include text, embedded media (e.g., using Panopto or Mediathread ) curated by the instructor, online discussion, and assessments. Students can be asked to read a case and/or watch a short video, respond to quiz questions and receive immediate feedback, post questions to a discussion, and share resources.

For more information about options for incorporating educational technology to your course, please contact your Learning Designer .

To ensure that students are learning from the case approach, ask them to pause and reflect on what and how they learned from the case. Time to reflect builds your students’ metacognition, and when these reflections are collected they provides you with insights about the effectiveness of your approach in promoting student learning.

Well designed case-based learning experiences: 1) motivate student involvement, 2) have students doing the work, 3) help students develop knowledge and skills, and 4) have students learning from each other.

Designing a case-based learning experience should center around the learning objectives for a course. The following points focus on intentional design.

Identify learning objectives, determine scope, and anticipate challenges.

- Why use the case method in your course? How will it promote student learning differently than other approaches?

- What are the learning objectives that need to be met by the case method? What knowledge should students apply and skills should they practice?

- What is the scope of the case? (a brief activity in a single class session to a semester-long case-based course; if new to case method, start small with a single case).

- What challenges do you anticipate (e.g., student preparation and prior experiences with case learning, discomfort with discussion, peer-to-peer learning, managing discussion) and how will you plan for these in your design?

- If you are asking students to use transferable skills for the case method (e.g., teamwork, digital literacy) make them explicit.

Determine how you will know if the learning objectives were met and develop a plan for evaluating the effectiveness of the case method to inform future case teaching.

- What assessments and criteria will you use to evaluate student work or participation in case discussion?

- How will you evaluate the effectiveness of the case method? What feedback will you collect from students?

- How might you leverage technology for assessment purposes? For example, could you quiz students about the case online before class, accept assignment submissions online, use audience response systems (e.g., PollEverywhere) for formative assessment during class?

Select an existing case, create your own, or encourage students to bring course-relevant cases, and prepare for its delivery

- Where will the case method fit into the course learning sequence?

- Is the case at the appropriate level of complexity? Is it inclusive, culturally relevant, and relatable to students?

- What materials and preparation will be needed to present the case to students? (e.g., readings, audiovisual materials, set up a module in CourseWorks).

Plan for the case discussion and an active role for students

- What will your role be in facilitating case-based learning? How will you model case analysis for your students? (e.g., present a short case and demo your approach and the process of case learning) (Davis, 2009).

- What discussion guidelines will you use that include your students’ input?

- How will you encourage students to ask and answer questions, summarize their work, take notes, and debrief the case?

- If students will be working in groups, how will groups form? What size will the groups be? What instructions will they be given? How will you ensure that everyone participates? What will they need to submit? Can technology be leveraged for any of these areas?

- Have you considered students of varied cognitive and physical abilities and how they might participate in the activities/discussions, including those that involve technology?

Student preparation and expectations

- How will you communicate about the case method approach to your students? When will you articulate the purpose of case-based learning and expectations of student engagement? What information about case-based learning and expectations will be included in the syllabus?

- What preparation and/or assignment(s) will students complete in order to learn from the case? (e.g., read the case prior to class, watch a case video prior to class, post to a CourseWorks discussion, submit a brief memo, complete a short writing assignment to check students’ understanding of a case, take on a specific role, prepare to present a critique during in-class discussion).

Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press.

Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846

Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Garvin, D.A. (2003). Making the Case: Professional Education for the world of practice. Harvard Magazine. September-October 2003, Volume 106, Number 1, 56-107.

Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29.

Golich, V.L.; Boyer, M; Franko, P.; and Lamy, S. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. Pew Case Studies in International Affairs. Institute for the Study of Diplomacy.

Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK.

Herreid, C.F. (2011). Case Study Teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. No. 128, Winder 2011, 31 – 40.

Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries.

Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar

Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153.

Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative.

Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002

Schiano, B. and Andersen, E. (2017). Teaching with Cases Online . Harvard Business Publishing.

Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44.

Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1).

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Additional resources

Teaching with Cases , Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Features “what is a teaching case?” video that defines a teaching case, and provides documents to help students prepare for case learning, Common case teaching challenges and solutions, tips for teaching with cases.

Promoting excellence and innovation in case method teaching: Teaching by the Case Method , Christensen Center for Teaching & Learning. Harvard Business School.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science . University of Buffalo.

A collection of peer-reviewed STEM cases to teach scientific concepts and content, promote process skills and critical thinking. The Center welcomes case submissions. Case classification scheme of case types and teaching methods:

- Different types of cases: analysis case, dilemma/decision case, directed case, interrupted case, clicker case, a flipped case, a laboratory case.

- Different types of teaching methods: problem-based learning, discussion, debate, intimate debate, public hearing, trial, jigsaw, role-play.

Columbia Resources

Resources available to support your use of case method: The University hosts a number of case collections including: the Case Consortium (a collection of free cases in the fields of journalism, public policy, public health, and other disciplines that include teaching and learning resources; SIPA’s Picker Case Collection (audiovisual case studies on public sector innovation, filmed around the world and involving SIPA student teams in producing the cases); and Columbia Business School CaseWorks , which develops teaching cases and materials for use in Columbia Business School classrooms.

Center for Teaching and Learning

The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) offers a variety of programs and services for instructors at Columbia. The CTL can provide customized support as you plan to use the case method approach through implementation. Schedule a one-on-one consultation.

Office of the Provost

The Hybrid Learning Course Redesign grant program from the Office of the Provost provides support for faculty who are developing innovative and technology-enhanced pedagogy and learning strategies in the classroom. In addition to funding, faculty awardees receive support from CTL staff as they redesign, deliver, and evaluate their hybrid courses.

The Start Small! Mini-Grant provides support to faculty who are interested in experimenting with one new pedagogical strategy or tool. Faculty awardees receive funds and CTL support for a one-semester period.

Explore our teaching resources.

- Blended Learning

- Contemplative Pedagogy

- Inclusive Teaching Guide

- FAQ for Teaching Assistants

- Metacognition

CTL resources and technology for you.

- Overview of all CTL Resources and Technology

- The origins of this method can be traced to Harvard University where in 1870 the Law School began using cases to teach students how to think like lawyers using real court decisions. This was followed by the Business School in 1920 (Garvin, 2003). These professional schools recognized that lecture mode of instruction was insufficient to teach critical professional skills, and that active learning would better prepare learners for their professional lives. ↩

- Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries. ↩

- Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press. ↩

- Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative. ↩

- Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK. ↩

- Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846 ↩

- Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153. ↩

- Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44. ↩

- Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1). ↩

- Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002 ↩

- Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar ↩

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

National Center for case study teaching in science

Student assessment, evaluating case discussion.

Business school case teachers do it all the time. It’s not uncommon for them to base the final course grade on 50% class participation. And this with 50-70 students in a class! This sends shudders up the spines of most science teachers. Yet, what's so tough about the concept? We are constantly making judgments about the verbal statements of our colleagues, politicians, and even administrators. Why can't we do it for classroom contributions?

Most of our discomfort comes from the subjective nature of the act, something that we scientists work hard to avoid in our work-a-day world. It may be that we are even predisposed to become scientists because we are looking for a structured and quantifiable world. Flowing from this subjective quandary is the fact that we feel we must be able to justify our grades to the students. We are decidedly uncomfortable if we can't show them the numbers. This is one of the reasons that multiple-choice questions have such appeal for some faculty.

But let’s take a look at how the business school people evaluate case discussion. Some of them try to do it in the classroom, making written notes even as the discussion unfolds, using a seating chart, and calling on perhaps 25 students in a period. As you might expect, this usually interferes with running an effective discussion. Other instructors tape-record the discussion and listen to it later in thoughtful contemplation. Most folks, however, sit down shortly after their classes with seating chart in hand and reflect on the discussion. They rank student contributions into categories of excellent, good, or bad, or they may use numbers to evaluate the students from 1 to 4 with 4 being excellent. They may give negative evaluations to people who weren’t prepared or were absent. These numbers are tallied up at the end of the semester to calculate the grade. And that’s as quantified as it gets.

I especially like mathematician/philosopher Blaise Pascal's view of evaluation: “We first distinguish grapes from among fruits, then Muscat grapes, then those from Condrieu, then from Desargues, then the particular graft. Is that all? Has a vine ever produced two bunches alike, and has any bunch produced two grapes alike?” “I have never judged anything in exactly the same way,” Pascal continues. “I cannot judge a work while doing it. I must do as painters do and stand back, but not too far. How far then? Guess ....”

Assignments

The simplest solution to case work evaluation is to forget classroom participation and grade everything on the basis of familiar criteria, say papers or presentations. This puts professors back in familiar territory. Even business and law school professors use this strategy as part of their grades. I’m all for this. In fact, I always ask for some written analysis in the form of journals, papers, and reports. Along with an exam, these are my sole bases for grades. I don’t lose sleep over evaluating class participation.

You can give any sort of exam in a case-based course, including multiple-choice, but doesn’t it make more sense to have at least part of the exam a case? If you have used cases all semester and trained students in case analysis, surely you should consider a case-based test. Too often we test on different things than we have taught.

Peer Evaluation

Some of the best case studies involve small group work and group projects. In fact, I strongly believe teaching cases this way is the most user-friendly for science faculty and the most rewarding for students. Nonetheless, even some aficionados of group work don’t like group projects. They say, how do you know who’s doing the work? Even if they ask for a group project, they argue against grading it. They rely strictly on individual marks for a final grade determination. I’m on the other side of the fence. I believe that great projects can come from teams, and if you don't grade the work, what is the incentive for participating? Moreover, employers report that most people are fired because they can’t get along with other people. Not all of us are naturally team players. Practice helps. So, I’m all for group work including teamwork during quizzes where groups almost invariably perform better than the best individuals. But we have to build in safeguards like peer evaluation.

“Social loafers” and “compulsive workhorses” exist in every class. When you form groups such as those in Problem-Based Learning (PBL) and Team Learning (the best ways to teach cases, in my judgment), you must set up a system to monitor the situation. In PBL it is common to have tutors who can make evaluations. Still, I believe it is essential to use peer evaluations. I use a method that I picked up from Larry Michaelsen in the School of Management at the University of Oklahoma.

At the beginning of every course I explain the use of these anonymous peer evaluations. I show students the form that they will fill out at the end of the semester ( Table 1 ). Then they will be asked to name their teammates and give each one the number of points that reflects their contributions to group projects throughout the course. Say the group has five team members then each person would have 40 points to give to the other four members of his team. If a student feels that everyone has contributed equally to the group projects, then he should give each teammate 10 points. Obviously, if everyone in the team feels the same way about everyone else, they all will get an average score of 10 points. Persons with an average of 10 points will receive 100% of the group score for any group project.

But suppose that things aren’t going well. Maybe John has not pulled his weight in the group projects and ends up with an average score of 8, and Sarah has done more than her share and receives a 12. What then? Well, John gets only 80% of any group grade and Sarah receives 120%.

There are some additional rules that I use. One is that a student cannot give anyone more than 15 points. This is to stop a student from saving his friend John by giving him 40 points. Another is that any student receiving an average of seven or less will fail my course. This is designed to stop a student from doing nothing in the group because he is simply trying to slip by with a barely passing grade and is willing to undermine the group effort. Here are some observations after many years of using peer evaluations:

- Most students are reasonable. Although they are inclined to be generous, most give scores between 8 and 12.

- Occasionally, I receive a set of scores where one isn’t consistent with the others. For example, a student may get a 10, 10, 11, and a 5. Obviously, something is amiss here. When this happens, I set the odd number aside and use the other scores for the average.

- About one group in five initially will have problems because one or two people are not participating adequately or are habitually late or absent. These problems can be corrected.

- It is essential that you give a practice peer evaluation about one-third or one-half of the way through the semester. The students fill these out and you tally them and give the students their average scores. You must carefully remind everyone what these numbers mean, and if they don't like the results, they must do something to improve their scores. I tell them that it is no use blaming their group members for their perceptions. They must fix things, perhaps by talking to the group and asking how to compensate for their previous weakness. Also, I will always speak privately to any student who is in danger. These practice evaluations almost always significantly improve the group performance. Tardiness virtually stops and attendance is at least 95%.

© 1999-2024 National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, University at Buffalo. All Rights Reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Teaching with Case Studies

The Case Study method is based on focused stories, rooted in reality, and provides contextual information such as background, characters, setting, and enough specific details to provide some guidance. Cases can be used to illustrate, remediate, and practice critical thinking, teamwork, research, and communication skills. Classroom applications of the case study method include:

- Socratic cross examination

- Directed discussion or research teams

- Public hearings or trials

- Dialogue paper (e.g., 10 exchanges between two characters from opposing sides of an issue that finish with a personal opinion or reflection)

At the Fifth Annual Conference on Case Study Teaching in Science hosted by the University of Buffalo-SUNY, two broad categories of case studies were identified (recognizing potential overlap):

- Open or Closed: Open cases are left to one’s interpretation and may have multiple correct or valid answers depending on the rationale and facts presented in the case analysis. Closed cases have specific, correct answers or processes that must be followed in order to arrive at the correct analysis.

- Analysis or Dilemma: Analysis Cases (Issues Cases) are a general account of “what happened.” Dilemma Cases (Decision Cases) require students to make a decision or take action given certain information.

Case Study Analysis Process

Based on a variety of different case study analysis models, we have identified four basic stages students follow in analyzing a case study. This process may vary depending on discipline and if case studies are being used as part of a problem-based learning exercise.

- Observe the facts and issues that are present without interpretation (“what do we know”).

- Develop hypotheses/questions, formulate predictions, and provide explanations or justifications based on the known information (“what do we need to know”).

- Collect and explore relevant data to answer open questions, reinforce/refute hypotheses, and formulate new hypotheses and questions.

- Communicate findings including citations and documentation.

How to Write a Case Study

Effective case studies tell a story, have compelling and identifiable characters, contain depth and complexity, and have dilemmas that are not easily resolved. The following steps provide a general guide for use in identifying the various issues and criteria comprising a good case study.

- Identify a course and list the teachable principles, topics, and issues (often a difficult or complex concept students just don’t “get”).

- List any relevant controversies and subtopics that further describe your topics.

- Identify stakeholders or those affected by the issue (from that list, consider choosing one central character on which to base the case study).

- Identify teaching methods that might be used (team project, dialogue paper, debate, etc.) as well as the most appropriate assessment method (peer or team assessments, participation grade, etc.).

- Decide what materials and resources will be provided to students.

- Identify and describe the deliverables students will produce (paper, presentation, etc.).

- Select the category of case study (open or closed/analysis or dilemma) that best fits your topic, scenario, learning outcomes, teaching method, and assessment strategy. Write your case study and include teaching notes outlining the critical elements identified above.

- Teach the case and subsequently make any necessary revisions.

Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

PBL uses case studies in a slightly different way by providing a more specific structure for learning. The medical field uses this approach extensively. According to Barrows & Tamblyn (1980), the case problem is presented first in the learning sequence, before any background preparation has occurred. The case study analysis process outlined above is used with PBL; the main difference being that cases are presented in pieces, with increasing amounts of specific detail provided in each layer of the case (e.g., part one of the case may simply be a patient admission form, part two may provide a summary of patient examination notes, part three may contain specific medical test results, and so on).

The problem-based learning approach encourages student-directed learning and allows the instructor to serve as a facilitator. Students frame and identify problems and continually identify and test hypotheses. During group tutorials, case-related questions arise that students are unable to answer. These questions form the basis for learning issues that students will study independently between sessions. This method requires an alert and actively involved instructor to facilitate.

Guide to Teaching with Technology Copyright © 2019 by Centre for Pedagogical Innovation is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS)

The mission of the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) at SUNY-Buffalo is to promote the development and dissemination of materials and practices for case teaching in the sciences.

Click on the links below to learn more about-

- a bibliography of case studies,

- faculty perceptions on the benefit of teaching case studies, and

- research articles

Below is a sample work flow showing how to navigate the NCCSTS case collection. Enjoy!

1. Start at the NCCSTS homepage ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/ ). Then click on Case Collection (red arrow, upper right).

nccsts_front_page.png

2. Clicking on Case Collection takes you to the Keyword Search page. As shown below use the dropdown arrows to narrow your search parameters. As an example I chose Organic Chemistry under Subject Heading.

nccsts_keyword_search.png

3. Below is a partial list (6/25) of case studies categorized under the Subject Heading choice, Organic Chemistry.

nccsts_search_results.png

4. Click on a case study. I chose The Case of the Missing Bees (not shown in the partial list above). Below is a partial screenshot of the case study description. To download the case study click on the DOWNLOAD CASE icon (red arrow, upper right).

nccsts_download_case.png

5. Below is the the top of the first page of the case study, The Case of the Missing Bees .

nccsts_case_front_page.png

6. And of course make sure to review and adhere to the Permitted and Standard Uses and Permissions ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/collection/uses/ ).

nccsts_uses.png

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science

Case study title: The Case of the Missing Bees: High Fructose Corn Syrup and Colony Collapse Disorder

Case study authors: Jeffri C. Bohlscheid and Frank J. Dinan

- Student Login

- Educator Login

Creating an ExploreLearning Gizmos STEM Case

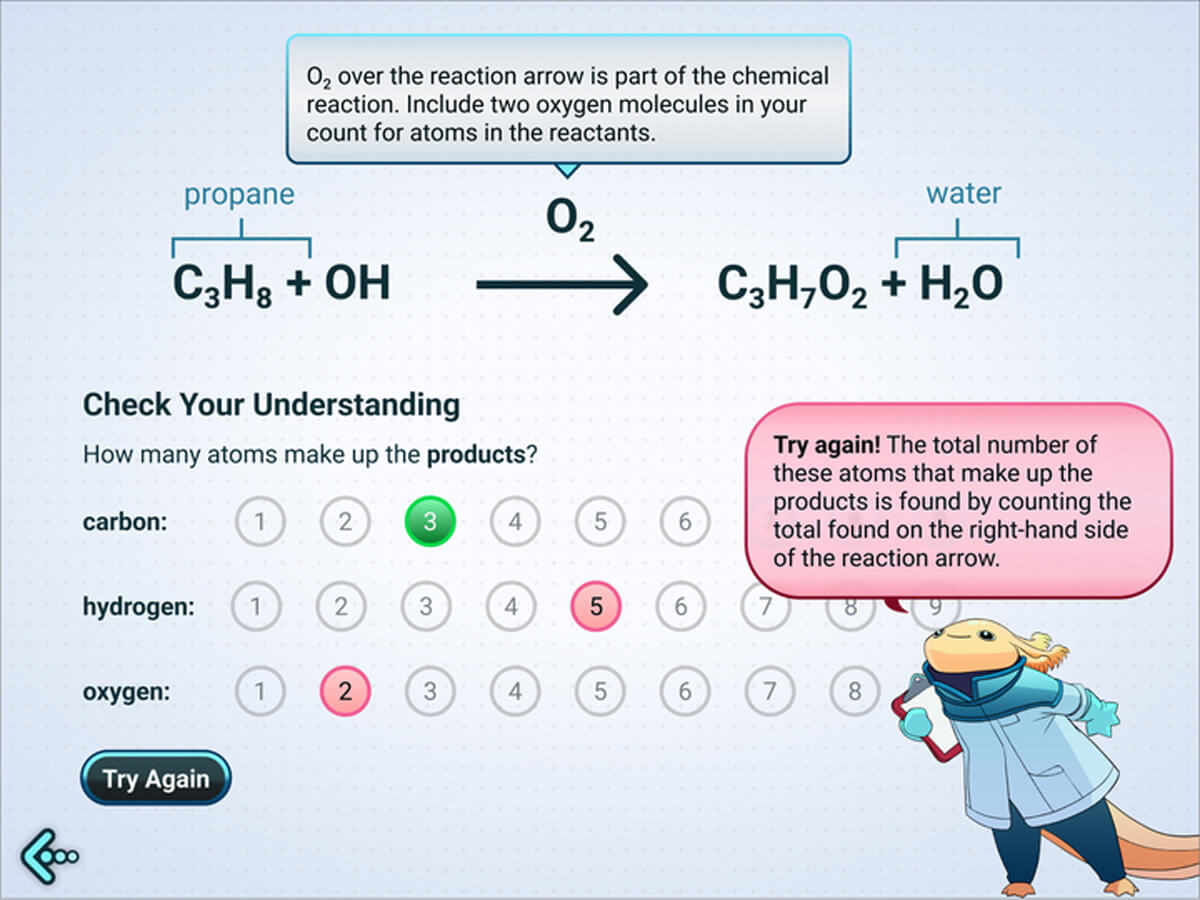

Teaching Strategies

Save a poisoned CIA agent, investigate counterfeit coins, reduce ozone levels? Ask any student, and they’ll likely tell you that’s not on their agenda between lunch and literature. But with ExploreLearning Gizmos STEM Cases , real-life problems come alive with interactive case studies that encourage students to find solutions like STEM professionals.

Brand new content

A respiratory physiologist is concerned about the number of children having asthma attacks in her community. Is something in the environment causing the increased rescue inhaler usage on certain days?

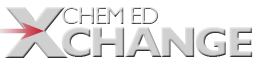

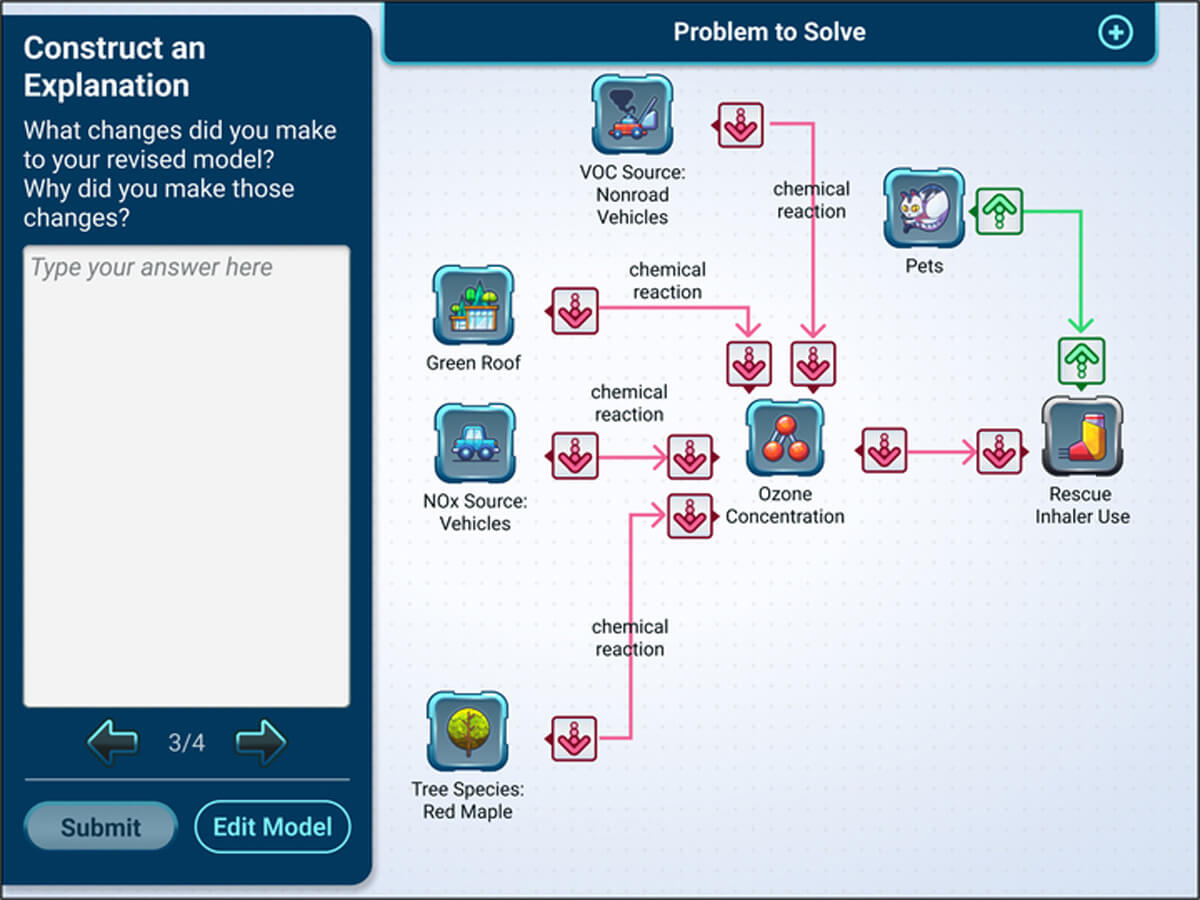

In ExploreLearning’s newest STEM Case, Smelling in the Rain: Designing Solutions to Improve Air Quality , middle school students act as air quality engineers to discover how some air pollutants are released directly from sources while others form through chemical reactions. Students develop system models to test solutions and recommend a plan to help decrease air pollution in a community with a record number of asthma cases.

In the STEM Case, students discover what ozone is, how it’s formed, the relationship between inhaler use and ozone levels, and more. Students analyze and interpret data and later design and test potential outcomes to reduce ozone concentration.

Students test, revise, and reflect on models in the Smelling in the Rain: Ozone STEM Case.

But behind students’ screens, there’s much more at play. Months of planning, research, testing, and development go into each STEM Case, and Smelling in the Rain is no exception. Let’s take a closer look at the teams that brought this STEM Case to life!

Topic selection

Before a storyline or colorful graphics existed, the ExploreLearning team intentionally brainstormed topics that aligned with content standards. Many states recently adopted new standards that integrate science content and practices, and the ExploreLearning team wanted to help teachers address and teach these revised standards in meaningful ways. “Standards come first. They are a big part of the decision-making process,” said Dr. David Kanter, Head of Science Solutions.

In 2023, the team has focused on expanding the already extensive library of middle school STEM Cases. ExploreLearning developers and learning designers looked to the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) since most state standards closely resemble the NGSS Science and Engineering Practices, Disciplinary Code Ideas, and Crosscutting Concepts. As the focus landed on a case study related to physical and Earth science, the Smelling in the Rain concept was born. “This STEM Case connects to a real-world problem while aligning with chemical reactions on a middle school level,” said Lauren Chiota, STEM Case Learning Designer.

Designing a learning experience

With a topic solidified, cross-functional teams collaborated to take the STEM Case from concept to reality. Initial outlines turned into play scripts, which later became full-fledged storyboards showcasing each screen a student might interact with. 2D and 3D artists worked to create exciting, realistic images and animations, including a brand-new character, Axl, who offers encouraging feedback and instruction throughout the learning journey. At various stages, Professional Development, Software Development, Content, and Science Solutions teams reviewed the case, and as it advanced, tested it with teachers who provided direct feedback.

Axl offers encouraging feedback as students learn about ozone formation in the STEM Case.

Smelling in the Rain led to other new learning tools that excited the ExploreLearning team, especially as they worked to incorporate a new “model builder” widget. Now, data analysis and testing come to life for students while teachers benefit from auto-scored activities and heatmaps to review learning as it happens. In the STEM Case, students adjust the ozone levels in a city by adding and removing items, such as trees or pollutants. “This new widget leans into the engineering design process. Students both design their solutions and demonstrate their understanding of the problem all in one place. Teachers see what students are thinking as they solve the problem and revise their models. This STEM Case gives students engaging and motivating opportunities to apply the engineering practices in multiple ways,” said Jared Jackson, Director of Production.

For newly released STEM Cases, including Smelling in the Rain, a new feature allows teachers to view and sort the reporting heatmap by “Practices” in addition to skills.

Collaboration is key

Outside experts also dedicated time and valuable input to make the STEM Case the most authentic and exciting experience for students. Dr. Patricia Silveyra , an Indiana University professor and researcher specializing in asthma and ozone exposure, assisted with the STEM Case from its onset.

As an ExploreLearning STEM Pro member, Dr. Silveyra provided expertise to help drive the STEM Case creation. She reviewed initial outlines and storyboards and shared valuable ozone knowledge to help the case study meet desired learning outcomes. “I like that STEM Cases are interactive. They walk students step-by-step into concepts. I like that they incorporate the latest research. They are very comprehensive with real-life examples of what’s going on in our environment and our labs,” said Dr. Silveyra.

“I’m contributing to STEM education, which is a very important mission for me.” -Dr. Patricia Silveyra

“I would highly recommend the STEM Pro program . It’s a very useful process to see how education is shaped by research. The staff is respectful of your time, and they accommodate to meet your needs. You will help students learn to apply and incorporate knowledge in better ways,” encouraged Dr. Silveyra.

Educators from the ExploreLearning Collab Crew also offered product development insight to shape the student STEM Case experience. “I love Collab Crew because it's very flexible, very rewarding professional development. I'm actually learning about a real-life situation or context that we will provide to the students. I feel like I'm helping ExploreLearning keep STEM Cases amazing, which they are. Also, I feel like I'm learning a ton, so it's a total win,” said Dr. Anna Scott, Upper School Science Department Chair in Athens, Georgia. Read Dr. Scott’s full interview here .

“We’ve worked with various teams over the last year to build a large database of expert teachers. Now, there is a large group of people to turn to for user testing and insight at all steps of the STEM Case creation process.” -Dr. David Kanter, Head of Science Solutions

A moment to celebrate

The official launch of the Smelling in the Rain STEM Case calls for a celebration! Congrats to the many teams and individuals who made this learning experience possible for students.

What’s your favorite part of the STEM Case development process?

“There’s so much complexity involved with each STEM Case. My favorite part of the process is working with cross-functional teams. We get a lot of early input from individuals using and testing portions of the STEM Case.” -Lauren Chiota , STEM Case Learning Designer

“Brainstorming. I enjoy thinking about the ‘how’ behind what students will be able to do in the STEM Case, from manipulating components to experiencing a new concept.” -Jared Jackson , Director of Production

“The moment I can email the entire ExploreLearning team that the STEM Case is published. I can breathe a sigh of relief!” -Dr. David Kanter , Head of Science Solutions

Smelling in the Rain is now available for students in grades 6-8.

Launch the STEM Case

Learn More:

For STEM Professionals:

For Educators:

You might also like these stories...

Who Has Authority over Their Knowledge? A Case Study of Academic Language Use in Science Education

- Published: 10 May 2024

Cite this article

- Catherine Lammert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7356-0816 1 ,

- Brian Hand ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0574-7491 2 &

- Chloe E. Woods 3

Explore all metrics

An important goal in early childhood science education is students’ development of academic language. However, scholars disagree on whether academic language must be explicitly taught or whether it can be learned through immersive science experiences. In this case study of a co-taught second grade classroom, we use positioning theory and framings of authority of knowledge to examine teachers’ and students’ use of both every day and academic language. Findings suggest that inside science classrooms operating as knowledge generation environments, students can claim authority over their own knowledge and teachers are able to position students as having this authority. Findings further suggest that when teachers take the stance of negotiator within these learning environments, students can develop academic language in science through immersive experiences. This study points to the importance of early childhood teachers operating as active negotiators with students within science classrooms to meet the goal of developing their academic language knowledge and skills.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

All names are pseudonyms.

Adair, J. K., Colegrove, K. S., & McManus, M. E. (2017). How the word gap argument negatively impacts young children of Latinx immigrants’ conceptualizations of learning. Harvard Educational Review, 87 (3), 309–453. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-87.3.309 .

Anderson, B. E., Wright, T. S., & Gotwals, A. W. (2023). Teachers’ vocabulary talk in early-elementary science instruction. Journal of Literacy Research , 55 (1), 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X231163117 .

Article Google Scholar

Biesta, G. J. J. (2017). The rediscovery of teaching . Routledge.

Biesta, G. J. J., & Safstrom, C. A. (2011). A manifesto for education. Policy Futures in Education , 9 (5), 540–547. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2011.9.5.540 .

Cavagnetto, A., R (2010). Argument to foster scientific literacy: A review of argument interventions in K-12 science contexts. Review of Educational Research , 80 (3), 336–371. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654310376953 .

Christie, F., & Derewianka, B. (2010). School discourse: Learning to write across the years of schooling . A&C Black.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed method research. (2nd ed.) SAGE.

Cummins, J., & Swain, M. (2014). Bilingualism in education: Aspects of theory, research and practice . Routledge.

Delpit, L. (1988). The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children. Harvard Educational Review , 58 (3), 280–299. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.58.3.c43481778r528qw4 .

Ding, C., Lammert, C., Fulmer, G. W., Hand, B., & Suh, J. K. (2023). Refinement of an instrument measuring science teachers’ knowledge of language through mixed method. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research, 5 (12), https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-023-00080-7

Georgia Department of Education (2016). Get Georgia Reading Retrieved from: https://getgeorgiareading.org/cabinet/dph-2/ .

Gibbs, A. S., & Reed, D. K. (2021). Shared reading and science vocabulary for kindergarten students. Early Childhood Education Journal , 51 , 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01288-w .

Hamel, E., Joo, Y., Hong, S. Y., & Burton, A. (2021). Teacher questioning practices in early childhood science activities. Early Childhood Education Journal , 49 (3), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01075-z .

Hand, B., & Cavagnetto, A. (2023). Brian’s life is not just another brick in the wall: Reframing the metaphor of science teaching. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy , [Ahead of print] https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2023.2284711 .

Hand, B., Cavagnetto, A., Chen, Y. C., & Park, S. (2016). Moving past curricula and strategies: Language and the development of adaptive pedagogy for immersive learning environments. Research in Science Education, 46 (2), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-015-9499-1 .

Hand, B., Chen, Y.-C., & Suh, J. K. (2021). Does a knowledge generation approach to learning benefit students? A systematic review of research on the science writing heuristic approach. Educational Psychology Review, 33 , 535–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09550-0 .

Haneda, M. (2014). From academic language to academic communication: Building on English learners’ resources. Linguistics and Education , 26 , 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2014.01.004 .

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms . McGraw-Hill.

Jensen, B., & Thompson, G. A. (2020). Equity in teaching academic language- an interdisciplinary approach. Theory into Practice , 59 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1665417 .

Kayı-Aydar, H. (2019). Positioning theory in applied linguistics . Palgrave Macmillan.

Keys, C. W., Hand, B., Prain, V., & Collins, S. (1999). Using the science writing heuristic as a tool for learning from laboratory investigations in secondary science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36 (10), 1065–1084.

Lammert, C., & Hand, B. (2022). Early childhood science teachers’ epistemic orientations: A foundation for enacting relational care through dialogue. Early Childhood Education Journal . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01427-x .

Lammert, C., Hand, B., & Sharma, R. (2023). Beyond pedagogy: The role of epistemic orientation and knowledge generation environments in early childhood science teaching. International Journal of Science Education, 45 (6), 431– 450. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2022.2164474 .

Manz, E. (2016). Examining evidence construction as the transformation of the material world into community knowledge. Journal of Research in Science Teaching , 53 (7), 1113–1140. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21264 .

Moghaddam, F., & Harré, R. (2010). Words of conflict, words of war: How the language we use in political processes sparks fighting . Praeger.

National Center for Education Statistics (2022). District search Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/districtsearch/district_detail.asp?ID2=1918120 .

National Research Council. (2012). A framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas . National Academies.

Naylor, S., Keogh, B., & Downing, B. (2007). Argumentation and primary science. Research in Science Education , 37 , 17–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-005-9002-5 .

Next Generation Science Standards Lead States. (2013). Next generation science standards: For states, by states . The National Academies Press.

Norton-Meier, L. (2005). A thrice-learned lesson from the literate life of a five-year-old. Language Arts , 82 (4), 286–295. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41483489 .

Nxumalo, F., Gagliardi, L. M., & Won, H. R. (2020). Inquiry-based curriculum in early childhood education . Oxford Research Encyclopaedia.

Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (2015). Early childhood education and care Retrieved from: https//www.oecd.org/edu/school/earlychildhoodeducationandcare.htm .

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004). The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective . Routledge.

Suh, J. K., Hwang, J., Park, S., & Hand, B. (2022). Epistemic orientation toward teaching science for knowledge generation: Conceptualization and validation of the construct. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 59 (9), 1651–1691. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21769 .

Takanishi, R. (2016). First things first: Creating the new American primary school . Teachers College.

Thompson, G. A., & Watkins, K. (2021). Academic language: Is this really (functionally) necessary? Language and Education , 35 (6), 557–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2021.1896537 .

Townsend, D. (2015). Who’s using the language? Supporting middle school students with content area academic language. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 58 (5), 376–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.374 .

Uccelli, P., & Phillips Galloway, E. (2016). Academic language across content areas: Lessons from an innovative assessment and from students’ reflections about language. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 60 (4), 395–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.553 .