Why Is Documentation Important in Nursing?

When a nurse is busy with a busy working day and many urgent demands on her time, keeping nursing records may seem like a distraction from the actual work of nursing: looking after your patients.

Nursing is a profession that requires the ability to care for patients and documents and communicate their treatments. A nurse in any setting needs to accurately document what they have done so that others who work with them are aware of all interventions.

In reality, keeping good records is part of the nursing care they provide for their patients. It is almost impossible for them to remember everything they do and everything that happens during a shift. If each patient’s nursing record is incomplete before the transfer, it will negatively impact their wellbeing.

The Documentation provides evidence-based information which can be used for future reference and research purposes. You must understand why documentation is important in nursing to provide comprehensive care for your patients. Because of this, we are sharing this complete guide.

Protecting Nurses

What is documentation.

Documentation is a necessity in almost every profession, but it has become a vital component of every employee’s role in health care.

It is essential to document every step of the process, from the time medication is given by a nurse to recording refrigerator temperatures by the head cook. Documentation helps to ensure routines are followed and fosters communication among staff in the same and different disciplines.

Documentation in nursing is crucial for patients’ continuity of care, determining clinical reimbursement, avoiding malpractice, and facilitating communication between rotating providers.

In simple words, Documentation is a record of a nationally organized account of the facts and observations about a particular subject. As nurses, they must document their patient’s daily progress to provide for continuity of care.

When Documentation is not done correctly, it can lead to possible lawsuits if there was an error or negligence on behalf of the nurse that led up to something wrong happening with their patient.

Why Should You Be Documenting?

You have to keep a record of everything to go back and refer to it in case of any questions. You are also protecting your nurses by documenting all interactions with patients when they have visitors, new orders for care, or anything that may be important.

Suppose the nurse ever suffers a medical emergency and their condition is not known because they failed to document everything. In that case, nobody will know how long ago this happened, which could result in other health complications down the line.

The main point is documentation protects nurses as well as patients, so make sure there’s an easy way to keep track.

Also, this protects nurses as well; with proper documentation, they can’t be blamed for things they didn’t do or said incorrectly. Hospitals also benefit from having records on hand because if someone were ever to sue them, or a nurse for malpractice , they prove medical mistakes did or did not occur.

Otherwise, by presenting their documented notes that show where and when errors may have happened, nursing students learn better when teachers use examples from real-life experiences since these are ones that you have to record.

What Kind of Information Do You Record?

In the nursing profession, every step you take is significant for a patient’s life and your own. That is why it is necessary to keep track of all the information you gathered about a patient, the medication they are taking, etc. You should also record any changes in their condition with time so that if anything happens, you can refer back to old records for help or diagnose them again.

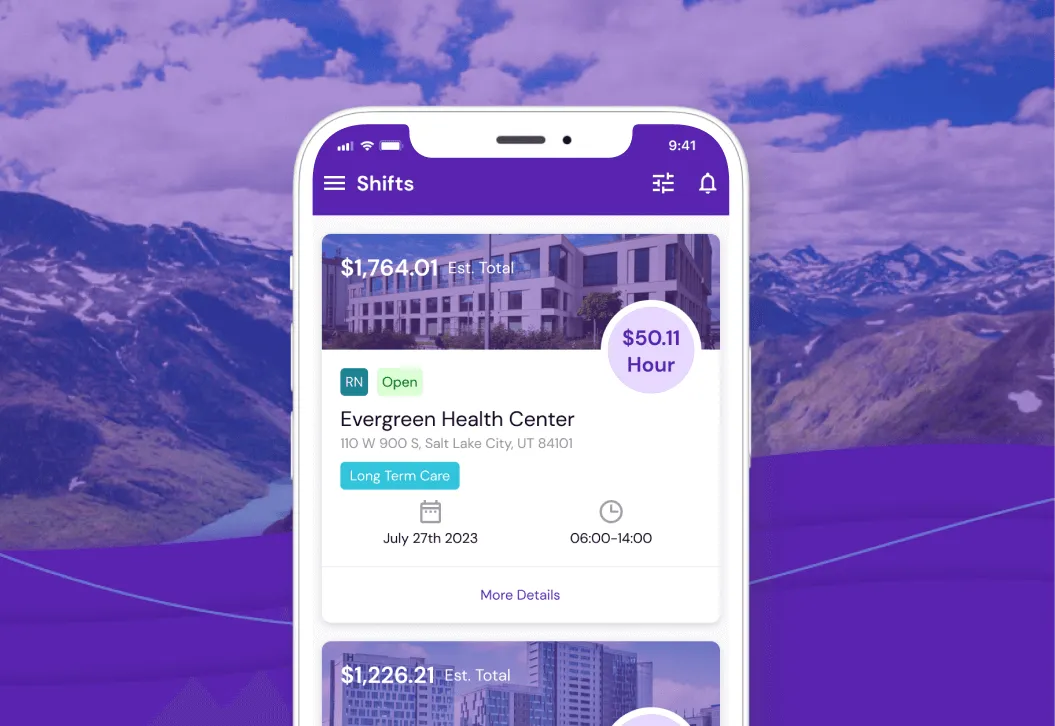

In today’s world, where everything is being digitized and transferred from one place to another virtually, many new devices are coming out every day, which makes recording much more straightforward.

One such device would be an electronic health records system (EHR). It makes your work easier because you no longer need paper charts at the nurse’s stations anymore.

But although EHRs save the nurse some trouble by providing an overview of data like blood pressure and heart rate, it can also be quite dangerous because there is no way to tell who may have accessed the data.

How does having proper records help your patients?

Now it comes to the main point about how keeping documentation can help you. The well-documented records can help you to identify the patterns of your patient’s health. It also helps in providing a clear picture of their mental status and physical condition. This way, it becomes much easier for you to work on preventive as well as curative measures.

The documented recordings do not only help to keep your patients healthy, but they even help you in getting an idea about how others’ care is going on with them, i.e., what changes have been happening since when.

The best thing about having proper Documentation is that now there will be no discrepancies between different healthcare providers’ notes because every detail has been recorded correctly, and everyone knows where everything belongs.

Benefits of creating Documentation in Nursing

When we talk about benefits, it could be following:

- Reducing the chance of malpractice lawsuits,

- It is ensuring patient safety through accurate and complete Documentation.

- Record of medicines and treatments given to patients

- Improves the quality of care provided by hospitals.

- Allows for better communication with other healthcare providers and staff in a hospital setting

- Safety measure

The most important reason we should keep records is to ensure that there is a record of what was done if something goes wrong or somebody needs it. It can be used as evidence during legal proceedings, such as malpractice lawsuits or court cases.

This is a significant undertaking that requires accuracy and completeness when documenting patient treatment.

Patients are also protected if their medical records exist in electronic format because they provide proof regarding medications administered to them without needing the original containers to validate this information.

Recordkeeping allows physicians to communicate more effectively with other healthcare providers and staff within a hospital setting; it improves the overall quality of care delivered at hospitals, minimizes risk through accurate Documentation, facilitates continuity of care among healthcare personnel.

Conclusion on Why Is Documentation Important in Nursing

Documentation is a critical part of the healthcare field. It’s an opportunity to create and maintain records used as evidence in patient care, research, education, or legal proceedings.

By understanding what makes good nursing documentation so valuable to professionals and patients alike, you can better prepare yourself for your career and improve people’s quality of life.

More Resources

- Meaningful Use and the Continuity of Care Document

- Why Is the Nursing Process Important?

- Are Nurse’s Notes Becoming a Lost Art?

- Top Medical Abbreviations and Short Hand Fresh RN

About The Author

Brittney wilson, bsn, rn, related posts.

Civil War Nurse Facts

Nurse Staffing and Budget Cuts

7 Best Non-Slip Shoes

Nursing Graduation Party Ideas

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Start typing and press enter to search

ANA Principles

ANA excels at being a leader in nursing, creating guides to help create a safe environment for patients and medical professionals alike. Reports include principles and guidelines on various issues, designed to inform and instruct. Included here are these principles, created by ANA on important aspects of the nursing practice.

Principles for Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN) Full Practice Authority

While many are working to attain full practice authority for APRNs through legislative and regulatory efforts, analysis has revealed a disturbing trend in state legislation requiring a supervised post-licensure practice or transition period, often referred to as “transition to practice” requirements, further delaying APRN full practice authority. Increasing variability in state practice requirements for APRN full practice authority does not bring the nation toward consensus, but institutes additional layers of unnecessary regulatory constraint and higher costs.

ANA’s Principles for APRN Full Practice Authority provides policy-makers and stakeholders with evidence-based guidance when considering changes in statute or regulation for APRNs.

ANA Principles for Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN) Full Practice Authority

Essential Principles for Utilization of Community Paramedics

Over the past decade, Emergency Medical Services (EMS) has piloted a new role, most often referred to as the Community Paramedic (CP). This expanded role builds on the skills and preparation of the Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) and Paramedic, with the intention of fulfilling the health care needs of those populations with limited access to primary care services. Cuts in public health and community services funding have decimated programs, leaving unmet health needs. In many cases, CPs are filling a gap in services that had been performed by public health and visiting nurses.

ANA's Essential Principles for Utilization of Community Paramedics provides overarching standards and strategies for the Registered Nurse and the Community Paramedic to apply when cooperating in various settings and across the continuum of care. This document seeks to promote common understanding of the Community Paramedic role and clarification of Registered Nurses' expectations of cooperation with this new role.

ANA's Essential Principles for Utilization of Community Paramedics

Principles of Collaborative Relationships

The American Nurses Association and the American Organization of Nurse Executives developed these "Principles of Collaborative Relationships" to enhance highly effective practice environments. The Principles guide clinical nurses and nurse managers on functioning as teams to deliver on their shared goal of high-value patient care.

Principles for Social Networking and the Nurse

Online social networking facilitates collegial communication among registered nurses and provides convenient and timely forums for professional development and education. It also presents remarkable potential for public education and health guidance, contributing to nursing’s online professional presence. At the same time, the inherent nature of social networking invites the sharing of personal information or work experiences that may reflect poorly on a nurse’s professionalism. ANA’s Principles for Social Networking and the Nurse: Guidance for the Registered Nurse provides guidance to registered nurses on using social networking media in a way that protects patients’ privacy and confidentiality and maintains the standards of professional nursing practice. These six essential principles are relevant to all registered nurses and nursing students across all roles and settings.

ANA’s Principles for Social Networking and the Nurse

Principles for Pay for Quality

Today, in response to variations in the quality of health care and rising health care costs, many policymakers and purchasers of health care services are exploring and promoting pay-for-performance (P4P) or value-based purchasing (VBP) systems. There are multiple variations of Pay for Quality programs all with designs and strategies to refocus the health care system on cost-effective quality care. At the core of any program are the measures used to rate the provider’s performance. ANA’s Principles of Pay for Quality: Guidance for Nurses presents ten principles to guide the nurse in any Pay for Quality discussion.

ANA Principles for Pay for Quality

Principles for Nurse Staffing, 3rd Edition

The 2019 ANA Principles for Nurse Staffing identify the major elements needed to achieve optimal staffing, which enhances the delivery of safe, quality care. These principles and the supporting material in this publication will guide nurses and other decision-makers in identifying and developing the processes and policies needed to improve nurse staffing at every practice level and in any practice setting.

ANA's Principles for Nurse Staffing, 3rd Edition

Principles for Nursing Documentation

Clear, accurate, and accessible documentation is an essential element of safe, quality, evidence-based nursing practice. The RN and the APRN are responsible and accountable for the nursing documentation that is used throughout an organization. This publication identifies six essential principles to guide nurses in this necessary and integral aspect of the work of registered nurses in all roles and settings.

ANA Principles for Nursing Documentation

Principles of Environmental Health for Nursing Practice with Implementation Strategies

Nursing as a health care profession and environmental health as a public health discipline share many of the same roots. This document articulates and expands on ten principles to guide registered nurses in providing nursing care in a manner that is environmentally safe and healthy. By doing so, this document challenges nurses to rediscover their profession’s traditional environmental health roots and to operate from these roots and principles in their roles as health care advocates and providers.

ANA Principles of Environmental Health for Nursing Practice with Implementation Strategies

Core Principles on Connected Health

The American Nurses Association (ANA) Core Principles on Connected Health (Principles) is a guide for health care professionals who use connected health technologies to provide quality care.

These Principles are an update to the 1998 ANA Core Principles on Telehealth, which were developed through an interdisciplinary work group to help guide health care professions developing policy in the telehealth arena. For the latest iteration, the ANA Professional Issues Panel (Panel) leveraged a working definition of Connected Health (see below) to revise the Principles and reflect the current lens and transformation of health care. This definition is not an endorsement of ANA.

ANA Core Principles on Connected Health

Non-members can purchase ANA Principles PDFs through the ANA Bookstore.

Purchase ANA Principles

Item(s) added to cart

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Impact of Structured and Standardized Documentation on Documentation Quality; a Multicenter, Retrospective Study

1 Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Rudolf B. Kool

3 Radboud University Medical Center, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, IQ Healthcare, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Ludi E. Smeele

2 Department of Head and Neck Oncology and Surgery, Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Richard Dirven

Chrisje a. den besten, luc h. e. karssemakers, tim verhoeven.

4 Department of Oromaxillofacial Surgery and Head and Neck Surgery, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Jasmijn M. Herruer

Guido b. van den broek, robert p. takes, associated data.

Data is available upon reasonable request.

The reuse of healthcare data for various purposes will become increasingly important in the future. To enable the reuse of clinical data, structured and standardized documentation is conditional. However, the primary purpose of clinical documentation is to support high-quality patient care. Therefore, this study investigated the effect of increased structured and standardized documentation on the quality of notes in the Electronic Health Record. A multicenter, retrospective design was used to assess the difference in note quality between 144 unstructured and 144 structured notes. Independent reviewers measured note quality by scoring the notes with the Qnote instrument. This instrument rates all note elements independently using and results in a grand mean score on a 0–100 scale. The mean quality score for unstructured notes was 64.35 (95% CI 61.30–67.35). Structured and standardized documentation improved the Qnote quality score to 77.2 (95% CI 74.18–80.21), a 12.8 point difference (p < 0.001). Furthermore, results showed that structured notes were significantly longer than unstructured notes. Nevertheless, structured notes were more clear and concise. Structured documentation led to a significant increase in note quality. Moreover, considering the benefits of structured data recording in terms of data reuse, implementing structured and standardized documentation into the EHR is recommended.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10916-022-01837-9.

Introduction

Clinical documentation is the process of creating a text record that summarizes the interaction between patients and healthcare providers during clinical encounters [ 1 ]. The quality of clinical documentation is important as it impacts quality of patient care, patient safety, and the number of medical errors [ 2 – 4 ]. Furthermore, clinical documentation is increasingly used for other purposes, such as quality measurement, finance, and research. Additionally, regulatory requirements regarding documentation have increased [ 5 , 6 ]. Consequently, physicians are spending more and more time on documentation [ 7 ].

In recent years, various tools and techniques have been developed to increase documentation efficiency and decrease the time physicians need to spend on documentation. These techniques are known as content importing technology (CIT). Examples of CIT are copy and paste functions (CPF), automated data import from other parts of the electronic health record (EHR), templates, or macros. These tools seem to have multiple benefits, primarily faster documentation during patient visits. However, Weis and Levy described that the use of CIT has multiple risks. Incorrect insertion of data from other parts of the record, or excessively long, bloated notes can distract a reader from key, essential facts and data [ 8 ]. However, when used correctly, it should be possible to limit these risks.

In addition to the need to increase documentation efficiency, documentation needs to be accurate. Cohen et al. stated that variation in EHR documentation between physicians impedes effective and safe use of EHRs, emphasizing the need for increased standardization of documentation [ 9 ]. However, some studies have suggested that structured and standardized documentation (hereafter: structured documentation) can impede expressivity in notes. Rosenbloom explored this tension between flexible, narrative documentation and structured documentation and recommended that healthcare providers can choose how to document patient care based on workflow and note content needs [ 1 ]. This implies that structured documentation is preferred when reuse of data is desirable. On the other hand, narrative documentation can be used when reuse of information is not required.

Research has shown that structured documentation can improve provider efficiency and decrease documentation time [ 10 ]. Unfortunately, little is known about the effects that a transition from primarily unstructured, free-text EHR documentation to structured and standardized EHR documentation has on the quality of EHR notes. To date, research on this topic has mainly focused on the difference between paper-based and electronic documentation [ 11 – 13 ]. Although reuse of data, for which structured documentation is essential, will become increasingly important, the primary goal of EHR documentation is supporting high-quality patient care [ 14 ]. Therefore, the primary objective was to investigate the effect of increased standardized and structured documentation on the quality of EHR notes.

Since 2009, the Radboudumc Center for Head and Neck Oncology developed and implemented a highly structured care pathway. A care pathway is a complex intervention for the mutual decision-making and organization of care processes for a well-defined group of patients during a well-defined period [ 15 ]. In 2017, for all stages of the care pathway (e.g. first visit consultation, multidisciplinary tumor board, diagnostic results consultation, treatment, follow-up consultation) the patient information that had to be entered into the EHR was defined. Structured and standardized forms using different types of CIT, automated documentation and standardized response options were developed in Epic EHR (EPIC, Verona Wisconsin). These forms allowed physicians to enter all patient information efficiently into the EHR. This resulted in structured and standardized notes while simultaneously storing structured data elements into the EHR database. These data elements can be reused in other stages of the care pathway, automatically compute referral letters, trigger standardized ordersets, or other tools to make the care process more efficient. Ultimately, this data is used to populate real-time quality dashboards. Furthermore, data can be extracted from the EHR and sent to third parties, such as quality and cancer registries or other health care centers when referring patients. Besides structured data recording, these forms support additional narrative documentation if needed or preferred. Recently, a similar highly structured care pathway with structured documentation based on the previously developed care pathway in Radboudumc, was implemented at the Head and Neck Oncology department in Antoni van Leeuwenhoek. In this center, HiX EHR (Chipsoft, Amsterdam) is used. Because of the difference in EHR vendor and the resulting variation in technical possibilities of the EHRs, there were slight differences in structured forms and notes in both centers. However, the structured forms that were built in center B remain highly similar to the forms used in Center A, as the forms and notes of Center A were shared with center B and were subsequently used in the development phase.

A multicenter, retrospective design was used to assess the difference in note quality in two tertiary HNC care centers. In center A, structured documentation has gradually increased in recent years. Therefore, the EHR notes of patients seen between January and December 2013 were compared with those of patients seen between January and December 2019. The transition to structured documentation in center B was more immediate due to implementing an EHR embedded care path that supports structured documentation. Therefore, the notes of patients seen between March and July 2020 were compared with those seen between January and April 2021. This shorter interval added to internal validity because it is less likely that other, time-related factors influenced the outcome. Notes of consultations of adult patients that completed at least one initial oncological consultation (IOC) or follow-up consultation (FUC) during the study period were eligible for inclusion. In both centers, a list of eligible notes was extracted from the EHR and for each consultation type and each documentation method, 36 notes were randomly drawn. In total, 288 notes were included. Subsequently, notes were carefully anonymized. All names, dates, and other identifying information were replaced with < name > , < date > , or otherwise masked. A translated example of a structured note is available as Electronic Supplementary Material (Online Resource 1 ). HNC care providers from center A were recruited to rate the notes collected in center B, and HNC care providers in center B were recruited to rate notes from center A to minimize bias. Each physician was assigned a random group of notes. However, unstructured and structured notes were evenly distributed among raters. Subsequently, notes were scored in a secured digital environment created in CastorEDC (Castor, Amsterdam), an electronic data capture platform.

The quality of the notes was assessed using the Qnote instrument, a validated measurement method for the quality of clinical documentation [ 16 ]. This instrument rates every element of a note individually, by using one or more of seven components (Table (Table1 1 ).

Elements and components of Qnote instrument

| Chief complaint | Sufficient information |

| History of present illness | Concise |

| Problem list | Clear |

| Past medical history | Organized |

| Medications | Complete |

| Adverse drug reactions and allergies | Ordered |

| Social and family history | Current |

| Review of systems | |

| Physical findings | |

| Assessment | |

| Plan of care | |

| Follow-up information |

The primary outcomes of this study were the quality of notes and note elements, measured by the Qnote instrument on a 100-point scale. Secondary outcomes included length of notes in words, mean component scores per note, and subjective quality measured by a general score given on a scale of 1–10.

Data were notated and analyzed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Two-way ANOVA was used to assess differences in note quality between before and after implementation of structured documentation. The Qnote grand mean score and element scores were outcome variables. The type of note, the originating center, and a dummy variable indicating the period in which the note was written were added as fixed factors. Two-tailed significance was defined as p < 0.05 or a 95% CI not including zero.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Netherlands Cancer Institute and Radboud University Medical Center.

The grand mean score of all 144 EHR notes written before implementing structured documentation was 64.35 (95% CI 61.30–67.35). When comparing this score to all 144 EHR notes written with structured documentation, a 12.8 point difference (p < 0.001) was found. Structured documentation improved the grand mean score to 77.2 (95% CI 74.18–80.21). Subsequently, additional analysis was conducted on all element scores. The results are shown in Table Table2 2 .

Estimated marginal means of Qnote scores and main effect of structured documentation

| | | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chief complaints | 84.0 | 93.3 | +9.3 (4.0 to 14.7) | 0.001* |

| HPI | 71.6 | 87.1 | +15.4 (7.8 to 23.1) | 0.000* |

| Problem list | 23.3 | 39.0 | +15.7 (3.9 to 27.6) | 0.009* |

| Past medical history | 38.8 | 47.0 | +8.2 (0.0 to 16.4) | 0.050* |

| Medications | 29.5 | 42.0 | +12.6 (–3.3 to 28.4) | 0.120 |

| Adverse reactions | 25.6 | 84.7 | +59.1 (47.2 to 71.0) | 0.000* |

| Social and family history | 72.5 | 88.3 | +15.8 (6.3 to 25.5) | 0.001* |

| Physicial findings | 82.8 | 85.3 | +2.5 (–2.2 to 7.2) | 0.293 |

| Assessment | 74.5 | 85.9 | +11.4 (5.1 to 17.7) | 0.000* |

| Plan of Care | 74.5 | 80.1 | +5.7 (–2.3 to 13.7) | 0.162 |

| Follow-up information | 72.5 | 86.9 | +14.4 (7.9 to 20.9) | 0.000* |

* difference significant (p < 0.05)

Table Table3 3 shows descriptive results of element scores displayed per type of note. What can be observed from the data in Table Table3 3 is that for structured documentation, the standard deviation decreases in most elements scores, indicating the variability in quality seems to be lower in structured notes. Furthermore, when comparing the grand mean score for IOC and FUC notes separately, an increase for both types of notes was found (Fig. 1 ). IOC Qnote score increased by 14.9 (95% CI 11.3–18.5) points from 67.3 to 82.3. FUC Qnote score increased by 10.8 (95% CI 4.6–17.0) from 61.3 to 72.1.

Descriptive results of Qnote element scores, per note type

| Chief complaints | 89,4 | (22,2) | 97,2 | (11,5) | 78,6 | (30,2) | 89,4 | (23,8) |

| HPI | 87,4 | (27,7) | 97,4 | (8,6) | 55,8 | (46,4) | 76,7 | (36,3) |

| Problem list | 33,8 | (46,6) | 46,5 | (49,0) | 12,7 | (33,1) | 31,5 | (45,8) |

| Past medical history | 73,7 | (41,5) | 85,2 | (31,6) | 4,7 | (19,1) | 8,0 | (26,6) |

| Medications | 29,5 | (45,3) | 42,0 | (49,5) | * | |||

| Adverse reactions | 25,6 | (40,0) | 84,7 | (31,1) | * | |||

| Social and family history | 72,5 | (36,2) | 88,3 | (19,4) | * | |||

| Physicial findings | 87,3 | (15,5) | 87,0 | (16,4) | 78,2 | (26,5) | 83,6 | (20,6) |

| Assessment | 83,3 | (20,6) | 88,3 | (18,7) | 65,8 | (39,3) | 83,6 | (23,5) |

| Plan of Care | 80,1 | (25,1) | 89,6 | (17,3) | 69,3 | (41,0) | 69,9 | (43,4) |

| Follow-up information | 63,9 | (32,1) | 88,0 | (22,0) | 81,0 | (27,9) | 85,7 | (27,1) |

| Grand Mean | 67,4 | (12,6) | 82,3 | (8,7) | 61,3 | (25,4) | 72,1 | (20,2) |

* grey marked elements were not evaluated for this note because these elements were considered not relevant in this type of consultation

Boxplot of grand mean score per note type

Subsequently, analysis was conducted on data from both centers separately to determine whether structured documentation led to increased quality in both centers. In center B, an increase of 14.59 was found (95% CI 7.22–21.96) in IOC note quality, and a 16.36 point increase (95% CI 8.99–23.73) in FUC note quality was found. A significant improvement in IOC Qnote score by 15.10 (95% CI 8.26–22.10) was observed in center A. The 5.3 point increase in FUC note quality was not statistically significant (95% CI -1.61–12.14).

Analysis of secondary outcome measures showed a significant increase in note length for structured documentation in both note types. IOC notes increased from 442.1 to 639.6 words, with a mean difference of 197.5 (95% CI 146.9–248.1), translating to a 44.7% increase. A significant 53.3% increase was found in FUC notes, increasing with 46.5 words (95% CI 31.7–61.2) from 86.9 to 133.4. To evaluate whether this increase in note length led to unnecessary long notes containing excessive non-essential information, all scores for a given component were averaged. For example, the component concise was used to rate 9 of the 11 elements used to rate a note. The mean of all conciseness scores was calculated to get an overall indication of the conciseness of the note. Table Table4 4 shows the difference in mean component scores. As can be seen from the data in Table Table4, 4 , the mean conciseness score, indicating whether note elements were focused and brief, increased significantly. Furthermore, the mean clearness score, indicating whether note elements were understandable to clinicians, also increased significantly.

Mean component score difference between unstructured and structured documentation

| | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sufficient information (7) | Enough information for purpose | +14.3 (10.2 – 18.4) | < 0.001* |

| Concise (9) | Focused and brief, not redundant | +10.7 (6.5 – 14.9) | < 0.001* |

| Clear (8) | Understandable to clinicians | +14.8 (10.6 – 18.9) | 0.009* |

| Organized (3) | Properly grouped | +14.5 (7.8 – 21.2) | < 0.001* |

| Complete (3) | Adresses the issue | +7.9 (1.61 – 14.3) | 0.014* |

| Ordered (1) | Order of clinical importance | +16.2 (4.5 – 27.9) | 0.007* |

| Current (3) | Up-to-date | +24.5 (17.3 – 31.7) | < 0.001* |

When analyzing the scores of the general instrument that rated the notes on a scale of one to ten, a significant increase in documentation quality was also found. Mean scores increased from 6.83 to 7.52, which was an 0.68 increase (95% CI 0.44–0.94).

The study offers some important insights into the impact of increased structured and standardized documentation on EHR note quality in outpatient care. In this retrospective multicenter study, our results show that structured documentation is associated with higher quality documentation. In summary, our results show a 20.0% increase measured on a 0–100 scale. Furthermore, results showed that structured notes were significantly longer than unstructured notes, but were more concise nevertheless.

This study showed an overall increase in documentation quality after the implementation of structured and standardized recording. In 8 of the 11 elements measured with the Qnote instrument, a significant increase in quality was found. This result may be explained by the fact that relevant elements and items that have to be documented are presented to the health care provider in an intuitive, uniform way. Therefore, clinicians are less likely to forget certain elements and items within the note. Furthermore, repeatedly recording in the same format ensures the physician is trained to record properly and completely. The medication element showed a minor, insignificant increase. This might be because medications were not included in notes in one center and therefore did not contribute to the observed results on this element. Additionally, minor, insignificant increases were found in physical examination and plan of care. This could be explained by the fact that the score for these elements was already high in unstructured documentation.

A recent study found variation in the quality of documentation between healthcare providers [ 9 ]. This variation could lead to inefficient documentation and the risk of patient harm from missed or misinterpreted information. Therefore, reducing this variability may also be considered relevant. The descriptive data on element scores in this study showed a trend indicating that the variation in documentation quality decreases when using structured documentation. However, some elements still showed significant variation. Therefore, implementing solutions that reduce variation in documentation quality between encounters and healthcare providers should be encouraged.

In addition, when the notes were analyzed differentiated by center, a significant increase in the quality of IOC notes was observed. This was also the case for follow-up notes in one of the two centers. This supports the conclusion that structured and standardized recording increases documentation quality, independent of a specific center or EHR vendor.

The results also show notes were longer when structured documentation was used. This could be because structured documentation contributes to including all relevant elements, or because health care providers are more reliant on CIT. CIT can be a problem if it leads to unnecessary, unorganized, or unclear information in a note and distracts the reader from the essential information buried within the note. This is known as note bloat. When considering the results of this study, there is no evidence that the longer notes were the result of note bloat. Firstly, an increase in quality in almost all elements where CIT is mainly used (problem list, past medical history, adverse reaction, social and family history) was observed. Secondly, the analysis on components used to assess the individual elements showed significant increases in clearness and conciseness. Therefore, it is safe to assume that in this study, the longer notes were not associated with note bloat and are most likely the result of more complete, and therefore higher quality, documentation.

The reports in the literature to date have mainly focused on the effect of electronic documentation versus handwritten documentation. Some studies have shown a perceived decrease in quality after implementing EHRs, identifying copy-paste functions (CPF) and note clutter as the main reasons for this quality decrease [ 17 ]. Others claim that EHRs increase note quality compared to manual recording in inpatient and outpatient care [ 11 – 13 , 18 ]. A small number of studies have evaluated semi-structured templates that mainly use free-text documentation, comparing them to traditional templates or fully unstructured free-text notes. A small (n = 36) trial comparing outpatient notes written using a traditional template with an optimized template found mixed results, with no difference in overall quality [ 19 ]. However, the intervention notes were inferior in accuracy and usefulness, although better organized. Another study evaluating a quality improvement project to improve clinical documentation quality found no increase in quality [ 20 ]. A third, larger study did find a significant increase in inpatient documentation quality using a semi-structured template [ 21 ]. The abovementioned studies indicate that further research on this topic is warranted. However, our findings show compelling evidence that structured documentation can improve documentation quality.

This study has several strengths. This is the first study to use a validated measure instrument for outpatient notes to examine the impact of structured and standardized recording on outpatient note quality. Given the rising demand for reuse and exchange of healthcare data, structured and standardized data recording will become increasingly important. This study proves that structured documentation can also improve the quality of EHR notes. Furthermore, the increase in quality was found in two centers with different EHRs. These factors contribute to the generalizability of the results.

Another strength of this study is the method used to assess the quality of the notes. Of the instruments available in the literature that are used to assess the quality of documentation, most focus on the absence of data or only assess the global quality of the note, such as the PDSI-9 [ 22 ]. However, the Qnote instrument is based on a qualitative study in which relevant elements of an outpatient clinical note were identified [ 23 ]. Therefore, it is possible to rate the quality of all note elements independently and subsequently calculate a total score. This structured approach is likely to be more objective than other, more general rating instruments. Besides, rating elements individually benefit from being able to identify specific deficits in note quality. Because of this, improving the quality of clinical EHR notes can be conducted in a more targeted and effective way.

This study also has some limitations. Firstly, the main limitation of the retrospective nature of this study is that a causal relationship between the implementation of structured and standardized documenting cannot be established with certainty. In one center, the interval between the two study periods was several years. Therefore, the influence of other factors cannot be eliminated. In the other center, the interval between study periods is shorter, making it highly likely that implementing the standardized care pathway with structured documentation is the primary reason for the increase in note quality. Moreover, analyzing the data differentiated by center resulted in similar outcomes. Secondly, the Qnote instrument has been validated on a population of diabetic patients and not for oncological patients. However, the elements used are general and not disease- or setting-specific. Moreover, the general score given by the raters in this study showed similar or marginally lower scores than the Qnote instrument. This conclusion was also stated in the initial Qnote validation study [ 16 ]. Lastly, due to the visual similarity of structured and standardized notes, the complete blinding of study notes for raters was impossible. This might have led to an unconscious bias. However, the risk was minimized by recruiting note raters employed at another hospital.

The findings of this study support the assumption that structured documentation positively influences documentation quality. This is an important finding, given that the need for structured documentation will only increase in the near future because structured data is key in enabling the reuse of healthcare data. Data reuse will become increasingly important in health care, for various purposes, such as automated quality measurement, information exchange when referring patients to other health care centers, and less time-consuming data collection methods for scientific research. Furthermore, the use and implementation of decision support tools also require structured recording of healthcare data. The abovementioned applications of data reuse in healthcare can lead to increased efficiency and quality of healthcare. Nevertheless, there could be a concern that as data reuse becomes more important, healthcare providers are required to capture more data while providing care. This, in turn, might lead to an increased administrative burden. This should be avoided, as healthcare providers are unlikely to accept a documentation method that adds a significant burden to their workload [ 24 ]. Efforts should be made to to implement structured documentation methods within EHRs to enable data reuse while reducing the administrative burden. The results of this study raise further questions about the benefits and pitfalls of structured documentation systems, on which future studies should focus. These include the effect of the structured documentation systems on documentation time and effort, how physicians' perceptions regarding the documentation process and the EHR are influenced, and how these factors affect adoption, and how these factors affect adoption. As a result, we have started another study to answer such questions.

This study demonstrated that structured and standardized recording led to an increase in the quality of notes in the EHR. Additionally, a significant increase in note length was found. Moreover, the results showed that the longer notes were also considered more clear and concise. Considering the benefits of structured data recording in terms of data reuse, it is recommended to implement structured and standardized documentation into the EHR.

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Data availability statement

Declarations.

None declared.

This article is part of the Topical Collection Clinical Systems

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

| | | |

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Revalidation

how to series

How to undertake effective record-keeping and documentation, nicola brooks associate dean (academic), faculty of health and life sciences, de montfort university, leicester, england.

• To familiarise yourself with the importance of keeping clear and accurate patient records

• To understand the approach for writing clear records that are free of jargon and speculation

• To learn about patients’ rights in relation to accessing their medical records

Rationale and key points

Effective record-keeping and documentation is an essential element of all healthcare professionals’ roles, including nurses, and can support the provision of safe, high-quality patient care. This article explains the importance of record-keeping and documentation in nursing and healthcare, and outlines the principles for maintaining clear and accurate patient records.

• Nurses’ regulatory standards for practice emphasise the importance of maintaining clear and accurate patient records.

• Patient records provide evidence of the assessments and interventions that have been undertaken. They can facilitate continuity of care by enabling other healthcare professionals to clearly see patients’ current care plans and treatments.

• The policies and procedures for maintaining patient records can vary between healthcare organisations, so it is important for nurses to check these and practice in accordance with them.

Reflective activity

‘How to’ articles can help to update your practice and ensure it remains evidence-based. Apply this article to your practice. Reflect on and write a short account of:

• How this article might enhance your practice, in terms of effective record-keeping and documentation.

• How you can use the information in this article to educate nursing students and colleagues on the importance and principles of effective record-keeping and documentation.

Nursing Standard . doi: 10.7748/ns.2021.e11700

This article has been subject to external double-blind peer review and checked for plagiarism using automated software

@Nicola44828048

None declared

Brooks N (2021) How to undertake effective record-keeping and documentation. Nursing Standard. doi: 10.7748/ns.2021.e11700

Disclaimer Please note that information provided by Nursing Standard is not sufficient to make the reader competent to perform the task. All clinical skills should be formally assessed according to local policy and procedures. It is the nurse’s responsibility to ensure their practice remains up to date and reflects the latest evidence

Published online: 15 March 2021

Nursing and Midwifery Council - professional - professional issues - professional regulation - record-keeping - The Code

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

05 June 2024 / Vol 39 issue 6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: How to undertake effective record-keeping and documentation

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

- Open access

- Published: 28 January 2022

Nursing documentation and its relationship with perceived nursing workload: a mixed-methods study among community nurses

- Kim De Groot 1 , 2 ,

- Anke J. E. De Veer 1 ,

- Anne M. Munster 3 ,

- Anneke L. Francke 1 , 4 &

- Wolter Paans 5 , 6

BMC Nursing volume 21 , Article number: 34 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

17 Citations

16 Altmetric

Metrics details

The time that nurses spent on documentation can be substantial and burdensome. To date it was unknown if documentation activities are related to the workload that nurses perceive. A distinction between clinical documentation and organizational documentation seems relevant. This study aims to gain insight into community nurses’ views on a potential relationship between their clinical and organizational documentation activities and their perceived nursing workload.

A convergent mixed-methods design was used. A quantitative survey was completed by 195 Dutch community nurses and a further 28 community nurses participated in qualitative focus groups. For the survey an online questionnaire was used. Descriptive statistics, Wilcoxon signed-ranked tests, Spearman’s rank correlations and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to analyse the survey data. Next, four qualitative focus groups were conducted in an iterative process of data collection - data analysis - more data collection, until data saturation was reached. In the qualitative analysis, the six steps of thematic analysis were followed.

The majority of the community nurses perceived a high workload due to documentation activities. Although survey data showed that nurses estimated that they spent twice as much time on clinical documentation as on organizational documentation, the workload they perceived from these two types of documentation was comparable. Focus-group participants found organizational documentation particularly redundant. Furthermore, the survey indicated that a perceived high workload was not related to actual time spent on clinical documentation, while actual time spent on organizational documentation was related to the perceived workload. In addition, the survey showed no associations between community nurses’ perceived workload and the user-friendliness of electronic health records. Yet focus-group participants did point towards the impact of limited user-friendliness on their perceived workload. Lastly, there was no association between the perceived workload and whether the nursing process was central in the electronic health records.

Conclusions

Community nurses often perceive a high workload due to clinical and organizational documentation activities. Decreasing the time nurses have to spend specifically on organizational documentation and improving the user-friendliness and intercommunicability of electronic health records appear to be important ways of reducing the workload that community nurses perceive.

Peer Review reports

Clinical nursing documentation is essential in letting nurses continuously reflect on their choice of interventions for patients and the effects of their interventions. Therefore, it is vital to the quality and continuity of nursing care [ 1 , 2 ]. Nursing documentation can be described as a reflection of the entire process of providing direct nursing care to patients [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Consequently, there is international consensus that clinical nursing documentation has to reflect the phases of the nursing process, namely assessment, diagnosis, care planning, implementation of interventions and evaluation of care or – if relevant – handover of care [ 2 , 3 , 6 , 7 , 8 ].

Despite the evident importance of nursing documentation, time spent on documentation can be substantial and therefore it can be experienced as onerous for nurses. Research indicates documentation time has reached an extreme form [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Even though the actual time spent by nurses on documentation varies internationally, it is a substantial part of the work of nurses [ 12 , 13 ]. For example, in Canada nurses spend about 26% of their time on documentation [ 14 ], in Great Britain 17% [ 15 ] and in the USA percentages vary from 25% to as much as 41% [ 16 , 17 ]. In the Netherlands, nursing staff reported spending an average of 10.5 hours a week on documentation [ 18 ], which means they spend about 40% of their time on documentation.

The variation between countries in nurses’ time spent on documentation may be related to differences in electronic health records and the way in which handovers are organized. However, the variation may also be the result of a lack of clarity about what qualifies as documentation [ 19 , 20 ]. Some studies used the term ‘documentation’ for activities that were directly related to individual patient care, e.g. drawing up a care plan or writing progress reports [ 16 , 17 ]. Other studies used ‘documentation’ as an umbrella term that included ‘non-patient-care-related’ documentation as well, such as recording hours worked or recording data for the planning of personnel [ 18 , 20 ].

A conceptual overview from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) provides more conceptual clarity in the various types of documentation [ 12 ]. The OECD states that documentation generally can be divided into clinical documentation and documentation regarding organizational and financial issues. Clinical documentation refers to documentation in the electronic health records of individual patients, e.g. about the patient’s medical condition and about the care provided by healthcare professionals. The OECD uses the term ‘organizational documentation’ to refer to the documentation of issues regarding personnel planning and coordinating different shifts, for instance. Documentation such as recording hours worked for the purpose of billing and insurance are categorized by the OECD as financial documentation [ 12 ].

There are indications that organizational and financial documentation in particular has increased in the last decade, which might be explained by the rising demand for accountability and efficiency of care [ 21 ]. Since documenting organizational and financial issues is not directly related to patient care, these aspects of documentation might be perceived negatively by nurses [ 22 ]. In contrast, nurses might be more open to clinical documentation since this documentation is essential to high-quality nursing care [ 1 , 2 , 23 ]. Moreover, according to professional standards and guidelines, clinical documentation should be considered as an integral part of providing nursing care [ 24 , 25 , 26 ].

Still, lengthy clinical documentation might be challenging for nurses as well. According to Baumann, Baker [ 27 ], Moore, Tolley [ 28 ] the implementation of electronic health records for individual patients appeared to increase the observed time that nurses spend on clinical documentation. Yet their findings were inconclusive, since long-term follow-up studies indicated decreasing documentation time once nurses became familiar with the electronic health records [ 27 ]. However, other studies indicated that the setup for the electronic health records does not always match nurses’ routines and can therefore be a potential source of perceived time pressure among nurses [ 29 , 30 ]. Yet when the electronic health records follow the phases of the nursing process, this might be supportive for nurses’ clinical documentation [ 31 ].

Nurses’ time pressure and nursing workload have received significant interest, in part because nursing shortages are a problem internationally [ 32 ]. Research often focusses only on the objective nursing workload, measured and expressed in actual time spent caring for a patient and/or staffing ratios [ 33 ]. However, nurses’ emotional or perceived workload might not always correspond to their objective workload [ 34 ]. But the perceived workload of nurses and the related factors is a rather unexplored area. For instance, it was unknown to date if perceived workload is associated with specific types of documentation activities and the actual time spent on these activities.

In line with the above-mentioned conceptual overview from the OECD [ 12 ] and from a nursing perspective, it seems relevant to make a distinction between different types of documentation activities. On the one hand, there is clinical documentation, which directly concerns the nursing care for individual patients. On the other hand, there is organizational and financial documentation; this is documentation that is mainly relevant for care organizations, management, policymakers and/or health insurers. In the Dutch context, clinical documentation often includes care needs assessment information, a care plan structured according to the phases of the nursing process, daily evaluation reports concerning the care given, and the handover of care. Organizational and financial documentation often concerns records of hours worked, expense claims for medical aids, reports on incidents with patients and/or employees, internal audits, and measurements of employee satisfaction and/or patient satisfaction.

To date it was unclear whether specific types of documentation are associated with a high perceived nursing workload. Distinguishing between types of documentation may provide more insight into the possible relationship between documentation and perceived nursing workload.

Furthermore, we used a mixed-methods approach to gain a deeper understanding, with a quantitative survey followed by qualitative focus groups. The quantitative data provided a broad and representative picture of the possible presence of a relationship between perceived workload and documentation activities. However, the reasons why community nurses felt the specific documentation activities increased their workload became clearer from the qualitative data. Combining the findings from these two methods resulted in a credible and in-depth picture of the relationship between documentation activities and perceived nursing workload. This enabled specific recommendations to be made that can help reduce the workload of nurses.

Such insights are relevant in particular for the home-care setting, since a previous survey showed that community nurses reported spending even more time on documentation compared with nurses working in other settings [ 18 ]. In addition, most studies on the documentation burden focus solely on the hospital setting, e.g. the studies of Collins, Couture [ 35 ] and Wisner, Lyndon [ 30 ].

Therefore, the study presented here aimed to gain insight into community nurses’ views on a potential relationship between clinical and organizational documentation and the perceived nursing workload (in this study, ‘organizational documentation’ includes financial documentation). The research questions guiding the present study were:

(a) Do community nurses perceive a high workload due to clinical and/or organizational documentation? ( survey and focus groups ), (b) If so, is their perceived workload related to the time they spent on clinical and/or organizational documentation? ( survey ).

Is there a relationship between the extent to which community nurses perceive a high workload and (a) the user-friendliness of electronic health records ( survey and focus groups ), and (b) whether the nursing process is central in the electronic health records ( survey and focus groups )?

A convergent mixed-methods design was used, in which a quantitative survey with qualitative focus groups were combined to develop in-depth understanding of the relationship between documentation activities and perceived nursing workload [ 36 , 37 ]. This design has been proven to be particularly useful for achieving a deep understanding of relationships [ 36 , 38 ]. First, the quantitative survey was performed and findings from this quantitative component were subsequently enriched by the findings of the qualitative focus groups [ 37 , 38 ].

Participants

Survey participants.

The nurses who were sent the online survey were participants drawn from a Dutch nationwide research panel known as the Nursing Staff Panel ( https://www.nivel.nl/en/panel-verpleging-verzorging/nursing-staff-panel ). Members of the Nursing Staff Panel are primarily recruited through a random sample of the population of Dutch healthcare employees provided by two pension funds [ 4 ]. In addition, members are recruited through snowball sampling and open calls on social media. All members had given permission to be approached regularly to answer questions about their experiences in nursing practice. For this study, the survey was sent by email to all 508 community nurses who were members of the Nursing Staff Panel. Since this is a nationwide panel, respondents worked in a variety of organizations across the Netherlands. To increase the response rate, two electronic reminders were sent to nurses who had not yet responded.

This paper focusses on community nurses and electronic nursing documentation; therefore only respondent nurses who met the following criteria were included in the analysis: 1) being a registered nurse with a bachelor’s degree or a secondary vocational qualification in nursing; 2) working in home care; 3) using electronic health records. We excluded 24 respondents who did not meet these criteria.

Focus-groups participants

Focus-group participants were recruited through the professional network of two authors (KdG and AM), open calls on social media (LinkedIn and Facebook), and through snowball sampling. Nurses were eligible to participate in a focus group if they met the same inclusion criteria as used for the survey participants. Purposive sampling was applied to obtain variation among participants regarding the educational level, age and standardized terminology used in the electronic health records. None of the participants of the focus groups had also participated in the survey.

Since the focus groups were in addition to the survey, we expected a priori that four focus groups would be enough to reach data saturation. This expectation was met, as the last focus group produced no new insights that were relevant for answering the research questions.

Data collection

The survey data were collected from June to July 2019. We used an online survey questionnaire that mostly consisted of self-developed questions as, to our knowledge, no instrument was available that included questions on both clinical documentation and organizational documentation. The extent to which nurses perceived a high workload was measured using a five-point scale (1 = ‘never’ to 5 = ‘always’). We distinguished between a high workload due to clinical documentation and a high workload due to organizational documentation. We included financial documentation in our definition of organizational documentation. In the questionnaire we explained the content of the two types of documentation. Respondents were then asked to estimate the time they spent on the two types of documentation.

Next, two questions focussed specifically on clinical documentation, namely whether the electronic health record of individual patients was user-friendly and whether the nursing process was central in this record. These questions were derived from the ‘Nursing Process-Clinical Decision Support Systems Standard’, an internationally accepted and valid standard for guiding the further development of electronic health records [ 31 ].

The entire questionnaire was pre-tested for comprehensibility, clarity and content validity by nine nursing staff members. Based on their comments, the questionnaire was modified, and a final version produced. A translation of the part of the questionnaire with the 11 questions relevant for this paper can be found at: https://documenten.nivel.nl/translated_questionnaire.pdf .

Focus groups

After the survey, we conducted four qualitative focus groups from February to May 2020. Each group consisted of six or eight community nurses, with a total of 28 community nurses. These focus groups were performed in order to deepen and refine the insights gained from the survey data.

The focus groups were led by two authors (KdG and AM) and supported by an interview guide with open questions, see Table 1 . The questions were inspired by the results of the survey data, e.g. they addressed how community nurses perceived clinical and organizational documentation in relation to their workload, or how community nurses experienced the user-friendliness of electronic health records.

Initially, we aimed to conduct all the focus groups face-to-face at the care organizations’ offices. However, after one face-to-face focus group we had to switch to online focus groups due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Online focus groups in which participants post written responses in a secure online discussion site have been proven to be an appropriate alternative for face-to-face focus groups [ 39 , 40 , 41 ]. In fact, the online focus groups had several advantages, such as providing participants with the ability to access, read and respond to posts at a place and time most convenient to them [ 40 , 41 ]. This was particularly advantageous for nurses during the pandemic.

Each online focus group was conducted within a set period of 2 weeks. Two authors (KdG and AM) acted as moderators by regularly checking the responses and posting new questions every 2 days, except in the weekend. The analysis of the transcripts has shown that the findings from the online focus groups were comparable to those from the face-to-face focus group.

Data analysis

Analysis of the survey.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the background characteristics of the respondents and to answer the first and second research questions. Wilcoxon signed-ranked tests were conducted to answer the first research question (1a), since the two variables measuring the perceived workload were ordinal and the two variables measuring the estimated time spent on documentation were not normally distributed. Next, the potential relationships between perceived workload and time spent on documentation (research question 1b) were examined using Spearman’s rank correlations. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were conducted to examine associations between perceived workload and user-friendliness (research question 2a) and the nursing process (research question 2b). The level for determining statistical significance was 0.05. Analyses were conducted using STATA, version 16.1.

Analysis of the focus groups

The audio recording of the face-to-face focus group was transcribed verbatim. Transcripts from the online focus groups were taken directly from the discussion site.

The focus-group transcripts were analysed using an iterative process of data collection - data analysis - more data collection. Within this process, the six steps of thematic analysis were followed, namely becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and reporting [ 42 ].

The transcripts of all the focus groups were analysed by two authors (KdG and AM). They refined their analyses in discussions together and with two other authors (AF and WP), which ultimate led to consensus about the main themes. This triangulation of researchers was used to increase the quality and trustworthiness of the analysis [ 43 ]. Moreover, ‘peer debriefing’ was applied with a group of peer researchers who were not involved in the study. In addition, confirmability of the findings was enhanced by including verbatim statements made by participants in the results section of this paper. Furthermore, the quality of the reporting was ensured by following the guidelines in ‘Good Reporting of A Mixed Methods Study’ [ 44 ].

Data integration

By integrating data from the quantitative and qualitative components, an in-depth and credible picture was obtained of the relationship between specific documentation activities and perceived nursing workload [ 36 , 37 ]. The data were integrated using two integration approaches. Firstly, we compared the data from the survey and focus groups in the analysis process, in discussions among the authors, and in the ‘ Discussion ’ section of this article. This is referred to as the ‘merging’ approach [ 37 ]. For instance, the survey result on how many nurses perceived a high workload from clinical documentation activities was compared to the focus groups results on nurses’ views as to why they did or did not perceive a high workload from these activities. Secondly, integration through narratives was performed when reporting the results. Hereby we used a ‘weaving’ approach in which we brought the findings from the quantitative survey and qualitative focus groups together on a thematic basis and arranged them according to the research questions [ 37 ].

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the General Data Protection Regulation, by strictly safeguarding the anonymity of the participants. Formal approval from an ethics committee was not required under the applicable Dutch legislation on medical scientific research as participants were not subjected to procedures and were not required to follow rules of behaviour (see https://english.ccmo.nl/investigators/legal-framework-for-medical-scientific-research/your-research-is-it-subject-to-the-wmo-or-not ).

Participants in the survey had all consented to being sent and completing surveys on a regular basis on topics directly related to their work when they signed up as members of the Nursing Staff Panel. Potential participants of the focus groups were informed about the study in an information letter. If desired, they could obtain additional verbal information. All participants signed an informed consent form before the focus groups started.

All methods were applied in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

A total of 195 community nurses completed the questionnaire (response rate 38.4%). Since a substantial group did not respond, we conducted non-response analyses. We found no statistically significant differences between the respondents and non-respondents regarding gender, level of education and number of hours employed. We did however see a difference in age: the respondents were somewhat older (mean age 49.8 years) than the non-respondents (mean age 44.3 years). We reflect on the relatively high age of the survey respondents in ‘ Limitations and strengths ’ section.

A total of 28 community nurses participated in the four focus groups. The characteristics of the participants are presented in Tables 2 and 3 .

Perceived workload due to documentation and time spent documenting

More than half of the community nurses in the survey said that they perceived a high workload due to clinical and/or organizational documentation, see Table 4 . A majority (52.4%) said that they regularly to always experienced a high workload due to clinical documentation. Regarding organizational documentation, 58% of the nurses reported a high perceived workload. No statistically significant differences in perceived workload were found between the two types of documentation (Wilcoxon signed-ranked test: p = 0.124). In other words, nurses were just as likely to experience a high workload due to clinical documentation as due to organizational documentation.

Community nurses in the survey estimated that they spent on average 8.0 (SD 6.0; median 6.0) hours a week on clinical documentation. They estimated that they spent significantly less time on organizational documentation, namely on average 3.6 (SD 4.0; median 2.0) hours a week (Wilcoxon signed-ranked test: p < 0.000).

Looking at clinical documentation, no statistically significant correlation was found between nurses’ estimated time spent on this type of documentation and their perceived high workload (Spearman’s rank correlation 0.135; p = 0.058). However, looking at organizational documentation, a statistically significant moderate correlation was found between time spent on documentation and perceived high workload (Spearman’s rank correlation 0.375; p < 0.000). This showed that nurses who spent more time on organizational documentation were more likely to perceive a high workload.

In general, the community nurses participating in the qualitative focus groups experienced a high workload due to documentation as well. They described organizational documentation in particular as cumbersome, redundant and too repetitive in nature. Even though nurses believed that a high workload in general is common among community nurses, they did see documentation as one of the causes for their high workload.

“You are already busy sorting out all the shifts, all the patients who are starting and stopping home care etc. There’s already a high workload. And on top of all that, there are the documentation activities. In our organization, they also want everyone to do refresher courses to keep their registration as a nurse, so you need to register that too. That is another extra documentation burden, and that takes up extra time too.” (Focus group 1, face-to-face).

A general picture that emerged from the focus groups is that organizational documentation was a key reason for community nurses’ perceived workload, while this was less so for clinical documentation. Community nurses in the focus groups said that they often failed to see the added value of organizational documentation for their patients and themselves. Therefore they had a feeling of frustration with the organizational documentation, associated with a high perceived workload.

“I think the frustration comes much more from the organizational side. From powerlessness because of all the pointless things you don’t really have time for.” (Focus group 1, face-to-face).

Focus-group participants mentioned that various rules and regulations imposed by their employers and/or national organizations, such as health insurers, also affected the amount of organizational documentation. They perceived a high workload when they had to register information only for the sake of these rules and regulations.

“Whenever someone in the organization starts talking about reducing the documentation burden, my blood pressure starts to rise. Then I know for certain that it’ll come back in spades some other way: someone else’s documentation burden will be reduced, but not mine.” (Focus group 1, face-to-face).

Community nurses in the focus groups were more positive about their clinical documentation activities. They found clinical documentation necessary and useful for providing good nursing care. For them it was evident that this documentation was an important part of their work. Because they saw clinical documentation as directly connected to individual patient care, they were less negative about the time they had to spend on clinical documentation compared with organizational documentation. Some nurses did however mention that documenting the formal care needs assessment (which is a requirement for home care financed by health insurers in the Netherlands) consumed a lot of their time. Still, nurses did not find this kind of documentation burdensome due to the perceived relevance and usefulness of the documentation of the care needs assessment. This was also the case for clinical documentation relating to individual patient care in general.

“The documentation activities I carry out for my patients are appropriate for my job and the documentation is not an additional burden. On the contrary, that documentation helps me and my fellow nurses to give our patients good, appropriate care.” (Focus group 4, online).

Perceived workload and features of electronic health records

Elaborating further on clinical documentation specifically, we explored the perceived workload in relation to two features of the electronic health records, namely user-friendliness and whether the record matches with the nursing process.

User-friendliness of electronic health records in relation to workload

Most of the community nurses in the survey agreed that the electronic health records in which they documented information about the nursing care for individual patients were user-friendly (78.8%). A smaller group disagreed (17.6%) and a few did not know (3.6%). The survey participants who answered ‘don’t know’ were excluded from the analysis of the association between user-friendliness and the perceived workload. No statistically significant association was found between how often the nurses perceived a high workload and the user-friendliness of electronic health records (Wilcoxon rank-sum test: p = 0.166), see Table 5 .

As for the user-friendliness of electronic health records the opinions and experiences of the community nurses in the qualitative focus groups were divided. While several community nurses were positive about the user-friendliness of the electronic health records, others were less positive. The latter group said that the limited user-friendliness was one reason why they spent so much time on documentation and experienced a high workload. Elaborating on the limited user-friendliness, nurses in the focus groups explained that some mandatory sections or headings in the electronic health records, e.g. about wound care, cost them too much time. They did not always see the added value of filling in those sections, making this a burdensome activity. Furthermore, nurses stated that the fact that they often had to switch between different sections of the electronic health record was time-consuming and burdensome for them as well.

“I also find it a pain that you need to search in different sections for a lot of things. The care plan describes that you have to perform wound care according to the wound policy, but the wound policy itself is under a different heading than the care plan. Then the reports about the wound are under the care plan again. And if the patient also needs help with ADL, you have to go back via the care plan again. It all costs extra time and you have to do a lot of clicking.” (Focus group 3, online).

Focus-group participants also addressed another issue regarding the limited user-friendliness of the electronic health records in relation to their workload. This is the large diversity in electronic systems used within and across care organizations and professionals. For instance, nurses said that they used different systems for documenting wound care and for documenting the medication check. Furthermore, other healthcare professionals, such as general practitioners or pharmacists, often use different electronic systems for their clinical documentation. Community nurses stated that these systems are often not linked to one another, resulting in duplicate documentation activities for nurses and increasing their workload.

“We have at least a dozen systems and only a few are linked to each other. [...] The systems for communicating with other disciplines and medication systems aren’t linked to one another. Despite the positive discussions, you’re still dependent on the preferences of the pharmacist or GP as to what systems are used. That can lead to you having three different medication systems in one team, for example.” (Focus group 4, online).

Nursing process in electronic health records in relation to workload