Beyond Intractability

The Hyper-Polarization Challenge to the Conflict Resolution Field We invite you to participate in an online exploration of what those with conflict and peacebuilding expertise can do to help defend liberal democracies and encourage them live up to their ideals.

Follow BI and the Hyper-Polarization Discussion on BI's New Substack Newsletter .

Hyper-Polarization, COVID, Racism, and the Constructive Conflict Initiative Read about (and contribute to) the Constructive Conflict Initiative and its associated Blog —our effort to assemble what we collectively know about how to move beyond our hyperpolarized politics and start solving society's problems.

By Conflict Management Program at SAIS Julian Ouellet

September 2003

| |

The United Nations was originally organized, "to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war."[1] To this end the United Nations established mechanisms for peacekeeping in the U.N. Charter [2] and the first peacekeeping operations (PKOs) were undertaken in the late 1950s. [3]

Though the terms are used differently by different groups, civil and international conflicts that require U.N. intervention can be seen as having three phases.

- In the first phase, violent conflict between parties is ongoing. At this point, "the objective of peacemaking is to end the violence between the contending parties" before peacekeeping forces enter the scene.[4]

- In phase two, a ceasefire has been negotiated, but conflict remains. The chief purpose of U.N. peacekeeping forces, therefore, is to reduce tensions between parties in conflict once a ceasefire has been negotiated so that peaceful relations can resume.

- By phase three, security threats have been diminished to the point that peaceful relations can resume, but often the state and civil society have been so ravaged by war that external efforts are required to rebuild infrastructure , political institutions, and trust among the contending parties. For this, peacebuilding or nation-building efforts are required.

It should be noted that some nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) describe peacekeeping as a component of peacebuilding . In this view, peacebuilding includes not only post-conflict demilitarization and nation-building efforts, but also preventive peacekeeping operations and peacemaking efforts.

In this essay, however, peacekeeping will be understood as the second phase of the peace process that is distinct from long-term peacebuilding. This reflects the United Nations' view that peacekeeping is an effort to "monitor and observe peace processes that emerge in post-conflict situations and assist ex-combatants to implement the peace agreements they have signed."[5] This includes the deployment of peacekeeping forces, collective security arrangements, and enforcement of ceasefire agreements. The so-called third phase of peacekeeping described above, on the other hand, is commonly regarded by the UN as part of peacebuilding. Thus, "this module will focus on the second phase of peacekeeping operations described above, the interposition of peacekeeping forces....."

This module will focus on the second phase of peacekeeping operations, the interposition of peacekeeping forces, in order to offer ideas about how peacekeeping can help intractable conflicts.

A Framework for Peace

| |

Any peacekeeping force is organized with the following six characteristics:

- neutrality (impartiality in the dispute and nonintervention in the fighting)

- light military equipment

- use of force only in self-defense[6]

- consent of the conflicting parties

- prerequisite of a ceasefire agreement

- contribution of contingents on a voluntary basis.[7]

These traits determine the size, composition, and limits of the mission. For example because the military personnel are lightly armed and require the consent of the parties involved, they are not capable of performing any peacemaking duties. At the same time, because peacekeeping forces are composed of military personnel, they are ill equipped to perform any state-building functions except in a support role. Given these constraints PKOs usually perform the following missions:

- preventive deployment to zones of conflict

- verification of cease-fire agreements , safe areas, and troop withdrawal

- disarmament and demobilization of combatants

- mine clearance, training, and awareness programs

- providing secure conditions for humanitarian aid and peacebuilding functions.

Within this framework solutions to violent intractable conflicts can be mediated and ameliorated. But we can also use the same guidelines to analyze whether PKOs are effective solutions for intractable conflicts. Opinions differ on this last point. Some feel that, though the solutions offered by PKOs may not be complete, in many situations they are the best that can be hoped for. One author argues, however, that according to the general framework of criteria for PKOs most have been failures.[8]

Cyprus is a good example of how difficult it is to judge a peacekeeping mission. Civil war broke out in the newly formed Republic of Cyprus in December of 1963.[9] By March of 1964 a U.N. Peacekeeping Force was deployed and became operational. Except for a coup d'etat in 1974, the peacekeeping force in Cyprus has been mostly successful in keeping the peace, but largely unsuccessful in reconciling the combatants. The United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) remains today.[10] This mixed bag of success and failure illustrates nicely the potential advantages and the potential problems inherent in most peacekeeping missions: on the one hand UNFICYP has been instrumental in maintaining an overall level of peace between the two sides; on the other hand, it has not reduced the conflict to the point that either side can feel secure were UNFICYP to leave.

We can see in the Cyprus example how a peacekeeping force organized around the principles of neutrality, light armaments, and mutual consent was able to verify the terms of the peace agreement and demobilize the combatants to a certain extent, but have largely failed in any goals of reintegration and state-building. The successes and failures of this mission provide some insight in the overall ability of PKOs in any operation.

The success of peacekeeping operations depends on two key issues. First, the peace agreement and/or ceasefire that the PKO is based on must be tenable for both sides. If one or both sides want to continue the fighting, a PKO will be very unlikely to maintain the peace.[11] Second, success is contingent on clear strategies for implementing nation-building and institutional development; simply put, democratization . PKOs that don't set out basic goals for building and maintaining trustworthy social institutions are not likely to experience high levels of success. Only in this context can peacekeeping forces prove to be effective solutions to intractable conflicts.

Fostering Peace

While the United Nations is not the only intergovernmental organization (IGO) to undertake peacekeeping missions, it is the most experienced. Since its ratification in 1945, the United Nations has deployed 55 PKOs. Remarkably, 42 of these have occurred since the end of the Cold War.[12] Depending on one's criteria for the success of a PKO, the number of U.N. missions that have been successful ranges from none to almost all of them. However, a standard evaluation of success is based not on a mission's peacekeeping ability alone, but also its peacebuilding ability. For example, Gregory Downs and Stephen Stedman use two criteria for evaluating a PKO, one of which has an implicit peacebuilding element to it:

- "whether large-scale violence is brought to an end while the implementers are present."

- "whether the war is terminated on a self-enforcing basis so that implementers can go home without fear of the war rekindling."[13]

Peace according to these criteria is the short-term absence of violence with the promise that this absence of violence might be lasting. Most research in the field agrees that peacekeeping forces are quite effective at accomplishing the first criteria, but have more trouble with the second. Thus we can say that the introduction of a PKO into a conflict is very effective at ending violence and establishing short-term peace, but less successful at maintaining that peace after they have left.

In the context of intractable conflict this may not be as damning as it seems: it is a question of degrees. After all, a stagnant partial peace is preferable to continued violence. Though building a stable and peaceful state may be preferable to maintaining peace through the continued presence of peacekeeping forces, the maintenance of peace in any form is preferable to continued violence. In these limited circumstances PKOs can offer a valuable solution to violent intractable conflicts.

The Will for Peace

However, no PKO would have any chance at success without a willingness by all parties to participate. Downs and Stedman focus this willingness on the political and economic will of outside powers to get involved in the peacemaking process.[14] That is, for any international or regional power to risk casualties, commit resources or use leverage, they must see their own interests as being affected by the continuation of the conflict. For Fen Hampson, willingness, or ripeness as he calls it, refers to the readiness of combatant parties to consider proposals that might alter the status quo.[15] Both definitions are valuable and lead us to conclude that, to foster peace, combatants must be willing to consider peace as an option, and external powers to consider peace as valuable and worthwhile. However, the latter consideration is most important for both peacekeeping and peacebuilding . Dennis Jett points out that PKOs often fail before they get started because of a failure of will on the part of the world powers.[16]

This was the case with Rwanda. A lightly armed U.N. Peacekeeping Mission led by Canadian Gen. Romeo Dallaire was in Rwanda before the genocide began. Dallaire's forces were 3,000 men strong. He requested another 2,000 men to use in a peacekeeping role. His request was turned down and subsequently 800,000 Rwandans (by some accounts) were killed in 100 days, mostly by machete. Here is a clear case where the lack of willingness on the part of the United Nations and its member states to commit to a peacekeeping effort led not only to massive failures in their peacekeeping mission, but allowed a genocide to happen while there was still time to prevent it. As Dallaire put it, "The explosion of genocide could have been prevented if the political will had been there and if we had been better skilled ... it could have been prevented."[17]

There is also evidence that if the political will is present among the major powers then the warring parties can be forced to the bargaining table. Jill Freeman cites previous research showing that international pressure is the key determinant in the success of security guarantees which are closely related to PKOs.[18] Looking back on Cyprus, we may be able to distinguish between the political will needed to initiate the peace agreement and the political will necessary to maintain that peace.[19] In this context we can understand the role of the international community in creating peace and the role of the conflicting parties in legitimizing the peacebuilding process.

At this point we have a good understanding of the definition of peacekeeping forces, their capabilities, the criteria for judging success, and the roles of the actors involved in ensuring that success. We have yet to answer the nagging question of how successful the various PKOs have been.

Peacekeeping?

As discussed, peacekeeping, since its beginnings over 50 years ago, has not been an overwhelming success. The ideal peacekeeping mission would have a clear entry plan, establish a lasting peace, and leave behind a set of stable institutions for ensuring that peace, all in the timeframe of two to three years. As it stands, of the 55 U.N. PKOs, 15 are ongoing. Of those, at least 10 have been going on for more than 10 years and five of these have been going on for more than 20 years.[20] Five of the 15 are too recent to be evaluated. Thus 10 of the 15 ongoing PKOs could be automatically labeled failures according to Downs and Stedman's criteria. Of the remaining 40 cases, Downs and Stedman only analyze 16, but of these only six qualify as unmitigated successes. PKOs do not have a promising track record. What can be done to improve the probability of success in peacekeeping missions?

Room for Improvement

We can agree that the goal of PKOs is admirable. We can also agree that even partial successes in intractable conflicts are desirable. However, it is not clear that PKOs have the ability to succeed in most conflicts. The goal of any PKO should not be to establish a marginally stable peace that lasts a few years, as is the case with Liberia or Zimbabwe, but to establish a lasting peace in which liberal institutions can be built, gain legitimacy, and guarantee peace, as is happening in Mozambique. PKO mandates that provide only for the interposition of forces between temporarily peaceful combatants have generally not worked and are not likely to work. The only hope for success in peacekeeping operations requires sustained interest from the international community, along with detailed plans for state building after the core goals of disarmament, demobilization, reintegration and reconstruction. These ideals have been clearly set out in Boutros Boutros-Ghali's Agenda for Peace as a matter of policy, but have yet to be realized as a policy in practice.[21]

[1] United Nations, The United Nations Charter Preamble [document on-line], (accessed on February 31, 2003); available from http://www.un.org/aboutun/charter/index.html Internet.

[2] Ibid, 2(4), 2(7), VI, VII, VIII

[3] Alan James, "Peacekeeping and Ethnic Conflict: Theory and Evidence" in Peace in the Midst of Wars: Preventing and Managing Ethnic Conflicts , eds. Carment, D. and P. James (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1998), 165.

[4] Conflict Management Toolkit, Peacekeeping: Definitions [document on-line] (accessed on February 12, 2003).

[5] United Nations, Ibid.

[6] http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/operations/principles.shtml#noforce

[7] Portions of this module were written by The Conflict Management Program as SAIS - Johns Hopkins

[8] Roland Paris, "Peacebuilding and the Limits of International Peacebuilding," International Security 22, no. 2 (Fall 1997): 53.

[9] United Nations, "UNFICYP: United Nation Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus: Background," [document on-line] (accessed on February 12, 2003); available from http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/missions/unficyp/background.html Internet.

[10] http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/missions/unficyp/background.html

[11] James Fearon, "Rationalist Explanations for War," International Organization 49, no. 3 (Summer 1995); Fen Hampson, Nurturing Peace (Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996), 8; Hugh Miall and others, Contemporary Conflict Resolution: The Prevention, Management and Transformation of Deadly Conflicts (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999), 164-7.

[12] Evan N. Resnick, "United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Ad Hoc Missions, Permanent Engagement (book review)," Journal of International Affairs 55 , no. 2 (Spring 2002), 539(6).

[13] need footnote

[14] George Downs and Stephen J. Stedman, "Evaluating Issues in Peace Implementation," in Ending Civil Wars: The Implementation of Peace Agreements , eds. Stedman, S., D. Rothchild, and E. Cousens (Boulder, CO: Lynne Reiner Publishers, 2002), 43.

[15] Hampson, ibid.

[16] FOOTNOTE NEEDED

[17] Quoted from Ted Barris, "Romeo Dallaire: Peacekeeping in the New Millennium," [document on-line] (accessed on 17 February, 2003); available from http://www.thememoryproject.com/Vol3Dallaire.pdf , Internet

[18] This is another essay in this system: Jill Freeman, Security Guarantees, available at http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/security-guarantees

[18] Hampson

[19] United Nations, http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/timeline/pages/timeline.html , Internet.

[19] Hampson, ibid.

[20] United Nations, "Operations Timeline," [document on-line] (accessed on 17 February, 2003); available from http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/timeline/pages/timeline.html , Internet.

[21] Boutros Boutros-Ghali, "An Agenda for Peace," [document on-line] (New York: United Nations, 1992, accessed on February 17, 2003); available from http://www.unrol.org/files/A_47_277.pdf , Internet.

Use the following to cite this article: Conflict Management Program at SAIS, and Julian Ouellet. "Peacekeeping." Beyond Intractability . Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: September 2003 < http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/peacekeeping >.

Additional Resources

The intractable conflict challenge.

Our inability to constructively handle intractable conflict is the most serious, and the most neglected, problem facing humanity. Solving today's tough problems depends upon finding better ways of dealing with these conflicts. More...

Selected Recent BI Posts Including Hyper-Polarization Posts

- Guy and Heidi Burgess Talk with David Eisner about Threats to Democracy and How to Address Them -- The Burgesses talked with David Eisner about what he thinks the threats to democracy are, and how (and when) we might respond to them. We agreed, citizen involvement in governance is key.

- Updating Our Impartiality Discussions - Part 1 -- The Burgesses update their 2-year old discussion of impartiality, adding to it Martin Carcasson's notion of "principled impartiality" which adds in quality information and "small-d" democracy.

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links for the Week of September 1, 2024 -- More in our regular set of links from readers, about colleague's activities, and from outside news and opinion sources.

Get the Newsletter Check Out Our Quick Start Guide

Educators Consider a low-cost BI-based custom text .

Constructive Conflict Initiative

Join Us in calling for a dramatic expansion of efforts to limit the destructiveness of intractable conflict.

Things You Can Do to Help Ideas

Practical things we can all do to limit the destructive conflicts threatening our future.

Conflict Frontiers

A free, open, online seminar exploring new approaches for addressing difficult and intractable conflicts. Major topic areas include:

Scale, Complexity, & Intractability

Massively Parallel Peacebuilding

Authoritarian Populism

Constructive Confrontation

Conflict Fundamentals

An look at to the fundamental building blocks of the peace and conflict field covering both “tractable” and intractable conflict.

Beyond Intractability / CRInfo Knowledge Base

Home / Browse | Essays | Search | About

BI in Context

Links to thought-provoking articles exploring the larger, societal dimension of intractability.

Colleague Activities

Information about interesting conflict and peacebuilding efforts.

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Beyond Intractability or the Conflict Information Consortium.

Beyond Intractability

Unless otherwise noted on individual pages, all content is... Copyright © 2003-2022 The Beyond Intractability Project c/o the Conflict Information Consortium All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced without prior written permission.

Guidelines for Using Beyond Intractability resources.

Citing Beyond Intractability resources.

Photo Credits for Homepage, Sidebars, and Landing Pages

Contact Beyond Intractability Privacy Policy The Beyond Intractability Knowledge Base Project Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess , Co-Directors and Editors c/o Conflict Information Consortium Mailing Address: Beyond Intractability, #1188, 1601 29th St. Suite 1292, Boulder CO 80301, USA Contact Form

Powered by Drupal

production_1

Peacemaking, peacekeeping, peacebuilding and peace enforcement in the 21st century

When we discuss peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding as a means to attain the UN Charter's goal “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war” we must make a distinction between peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peace enforcement. They reflect the express and implied boundaries and potential interpretations of chapters VI and VII of the UN Charter.

Chapter VI of the UN Charter talks about peacemaking as a non-restrictive list of peaceful, diplomatic, and judicial means of resolving disputes. Peacekeeping is situated before peace enforcement and before the sanctions regime as seen in chapter VII of the UN Charter. Peacebuilding is more than a process that has a broad post-conflict agenda and more than an instrumentalist method to secure peace. The Brahimi Report noted that effective peacebuilding includes “support for the fight against corruption, the implementation of humanitarian demining programmes and an emphasis on HIV/AIDS, education and control, and action against infectious diseases.”

An important part of peacebuilding includes reintegrating former combatants into civilian society, and strengthening the rule of law through training, restructuring local police, and through judicial and penal reform. Secondly, it includes improving respect for human rights through monitoring, education, and investigation of past and existing abuses, and providing technical assistance for democratic development like electoral assistance and support for free media, for example. Peacebuilding must include promoting conflict resolution and reconciliation techniques.

Peacebuilding is a quasi solidarity right that empowers popular action. The recent events in Ukraine is an example of popular action which comes as an applicability of this quasi-solidarity right. It supports the civil and political rights of the Ukrainian citizens by reassembling the foundation of peace through activities undertaken from the far side of the conflict in which democratic nations play an important role.

On the other side peacemaking is represented through activities such as mediation, conciliation, and judicial settlement. These elements of peacemaking are part of Boutros Boutros-Ghali's conceptual platform in his “ Agenda for Peace ”. M. Sarigiannidis (2007) argued that this agenda has been misapplied and not used as an essential foundation of UN principles and practices.

Peacebuilding and democratisation

Peacebuilding and democratisation is based on a proposed strategic framework which “ addresses the link between social and economic development, reconciliation and postconflict retributive justice, the development of political stability, and democratic governance. ”.

There must be a shift towards local capacity building, away from patronage and towards partnership. So far, the US model has failed to address these issues and continues the business as usual - neglecting the postconflict realities by continuing to enforce institutionalisation and competitive elections. These are the main causes of continuing violence in post-conflict societies, which have a very fragile democracy built into their governance system. Peacebuilding and democratisation must retain its original purpose by focusing in areas which consolidate peace in the short-term by managing the future through conflict prevention and reconciliation strategies rather than resorting to violence.

A strong peacebuilding strategy first of all involves reconstructing and/or strengthening legitimate and authoritative governance mechanisms. The next step is building local democratic capacities by using knowledge from appropriate segments of society to enhance the legitimacy of peacebuilding by adding post-conflict political reconstruction activities rather than institution building alone. There must be a shift towards local capacity building, away from patronage and towards partnership. All multilateral or bilateral strategies for democratisation need reformulation and retooling.

Let's talk about deductive versus inductive approaches to peacebuilding. The deductive approaches to peacebuilding are driven by donor tools and capacities which tend to favour institutions over processes and ultimately will result in failed or mixed outcomes. The inductive approach is focused on conflict parameters and strategies that are being employed. Local capacity building means that local priorities are identified at all levels of society. It is centred on peacebuilding processes rather than building institutions. Inductive strategies include managing conflict without violence, local participation, and the use of appropriate forms of knowledge.

The only way to achieve a lasting peace is by “ shifting the strategic enterprise from a deductive, structural perspective to an inductive, process-driven one brings local priorities to the fore, rather than subordinating them to donor priorities. ” The “chronic gap between pledges and delivery of aid jeopardize the consolidation of national peace and postconflict transitions.” (Shapard Forman and Stewart Patrick, 'Good Intentions: Pledges of Aid for Postconflict Recovery' 2000) The need for stable, effective, and legitimate forms of governance is imperative. We can note the latest developments in Ukraine, for example, to realize the need for conflict prevention and especially the need for inductive strategies of partnership with local agencies. “ Peacebuilding operations should be concerned about creating the conditions for the outcome that will lay the foundations for continued democratization. ”

Peacebuilders must be facilitators rather than be perceived as dominant occupiers. It is imperative to end the culture of dependency which was created by some international organisations. Instead we must resolve conflicts by using grassroots solutions and integration of local groups and organisations.

Peacebuilders must be facilitators rather than be perceived as dominant occupiers. It is imperative to end the culture of dependency which was created by some international organisations. A creative and effective initiative is to foster a legitimate traditional and culturally specific model of inter-group decision-making employing norms of democracy. Including local representatives at the highest level in planning and coordination of peacebuilding would increase the opportunities for participation in shaping the design of these missions and increase accountability.

Any peacebuilding activity that does not involve local traditional values and culture will not last. Any form of peace intervention, technical or financial aid and diplomatic work will fail if the local people are not consulted and involved in the process. Through recognition and shared authority given to the local organisations, their civil and political rights are enforced. It will lessen the power gap between government and citizens. A balance of power is necessary to maintain peace while a new and effective structure of governance is built in post-conflict societies.

A “ durable peace is not possible without stabilisation and structural reform.” International organisations should support a reform program that is consistent with the proposed agenda for peace. Such reform should have the following objectives :

- A greater transparency between actions of the different institutions and agencies through periodic and systematic exchange of information at the appropriate levels.

- An enhanced coordination between those bodies and agencies as well as integration of goals and activities so as to assist in a peace-related effort under the auspices of the UN.

- Flexibility in the application of rules of financial institutions or adjustment of such rules when UN preventive diplomacy, peacemaking or post-conflict peacebuilding so requires.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, “ peacebuilding is designed to build confidence among the parties, facilitate institutional reform, demobilize armies, and assist the reform and integration of police forces and judiciaries. ” Statistically, it is known that more than 86% of negotiated peace treaties last. These cases reflect the peace processes that are participatory and where the defeated join in the governance. They can compete for elected office and allow the opposition in power-sharing. The UN Secretary General's report, No Exit Without Strategy describes the three means of reconstructive peacebuilding. They are:

- Consolidating internal and external security;

- Strengthening political institutions by increasing effectiveness and participation;

- Promoting economic and social reconstruction.

Peace negotiations test the sincerity and the willingness of the parties to live with each other and indicates how well they can design a comprehensive blueprint for peace. They can mobilize the support of local interest groups in peacemaking. The foreign aid coming from the international community in support of implementing the peace-related activities is essential in establishing a commitment to promote human rights, economic, and social development.

So far, the United Nations has employed with success the four linked strategies of peacemaking, peacekeeping, peacebuilding, and peace enforcement. Such strategies promote the multinational and multilateral impartiality based on the principle of equality of states and universal human rights which are embedded in the UN Charter. The United Nations' multinational character is based on cross ethnic and cross-ideological cooperation between member states. The linked strategies for peace aim at achieving a lasting democratic change through reform and justice.

We hope you're finding Peace Insight valuable

More from gabriela monica lucuta →.

Canada as a peacemaker in action

Peacebuilder nations in action

Transforming women’s cultural roles into bridges for peacebuilding: Recounting the journey of Mrs Ariet Philip in the Gambella region of Ethiopia

Peacebuilder perspectives: Is the war the only way to end Myanmar’s internal conflict?

Instinctive and intuitive paths to peace: Rose Pihei’s authentic approaches towards Bougainville’s healing

Explore related peacebuilding organisations.

Submit an organisation: Is Peace Insight missing a peacebuilding organisation or initiative? Click here to tell us .

- All Articles

- Books & Reviews

- Anthologies

- Audio Content

- Author Directory

- This Day in History

- War in Ukraine

- Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

- Artificial Intelligence

- Climate Change

- Biden Administration

- Geopolitics

- Benjamin Netanyahu

- Vladimir Putin

- Volodymyr Zelensky

- Nationalism

- Authoritarianism

- Propaganda & Disinformation

- West Africa

- North Korea

- Middle East

- United States

- View All Regions

Article Types

- Capsule Reviews

- Review Essays

- Ask the Experts

- Reading Lists

- Newsletters

- Customer Service

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Subscriber Resources

- Group Subscriptions

- Gift a Subscription

The Astonishing Success of Peacekeeping

The un program deserves more support—and less scorn—from america, by barbara f. walter, lise morjé howard, and v. page fortna.

Many Americans believe that peacekeeping is ineffective at best and harmful at worst. They remember peacekeepers leaving at the first sign of trouble in Rwanda or standing inert as the Serbian army massacred Muslim civilians in Bosnia. They recall images of U.S. soldiers being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu. Every year, the Gallup organization asks Americans whether they think the United Nations is doing a good or bad job of trying to solve the problems it faces, and for the last 19 years, a majority of those sampled have given the organization a thumbs-down. The United Nations is especially disliked by Republicans. According to Gallup’s 2020 study, only 36 percent of the party’s members view the UN positively, the lowest number in almost 30 years.

These negative stories have been used to help justify the United States’ deep cuts to the UN’s peacekeeping budget. From 2015 to 2018, U.S. financial support for peacekeeping fell by 40 percent. The United States is the largest financial contributor to UN peacekeeping, and its cuts have reduced the overall budget from $8.3 billion to $6.4 billion, curtailing the organization’s ability to act. Although some of the most recent retrenchment is due to former President Donald Trump’s disdain for the UN, after nearly one year of unified Democratic control, Washington still has not fully paid for its peacekeeping obligations and is roughly $1 billion in arrears. As a result, there have been no newly fielded peacekeeping missions since 2014, despite an increase in civil wars. In diplomatic efforts to end conflicts in Afghanistan, Colombia, Ethiopia, Libya, Myanmar, Venezuela, and Yemen, third-party peacekeeping isn’t even on the table.

That is a shame, because the negative perceptions of peacekeeping are dead wrong. Decades of academic research has demonstrated that peacekeeping not only works at stopping conflicts but works better than anything else experts know. Peacekeeping is effective at resolving civil wars , reducing violence during wars, preventing wars from recurring, and rebuilding state institutions. It succeeds at protecting civilian lives and reducing sexual and gender-based violence. And it does all this at a very low cost, especially compared to counterinsurgency campaigns—peacekeeping’s closest cousin among forms of intervention .

To reduce violence around the world, the United States and its partners need to increase their financial and personnel support for peacekeeping missions. They must be more willing to greenlight campaigns, and they must invest in more training for peacekeeping forces. Washington has a geostrategic reason to act. China is stepping in to provide more resources for peacekeeping missions, and it appears to want to control more agencies within the United Nations, including the Department of Peace Operations. But the United States also has a moral imperative . A greater commitment to peacekeeping would bring more stability to the world, saving countless lives.

COUNTING THE WAYS

Scholars have researched the connection between third-party peacekeeping and violence in dozens of studies. As we explained in a recently published article on the effects of peacekeeping, these studies have remarkably similar findings . Although they used different data sets and models and examined different time periods and types of peacekeeping, the most rigorous studies all have found that peacekeeping has a sizable and statistically significant effect on containing civil war, getting leaders to negotiate settlements, and establishing a lasting peace once war has ended. Conflict zones with peacekeeping missions produce less armed conflict and fewer deaths than zones without them. The relationship between peacekeeping and lower levels of violence is so consistent that it has become one of the most robust findings in international relations research during the contemporary period.

This discovery would be striking in any circumstance. But the relationship is especially impressive given that the UN generally intervenes in the most difficult cases. Researchers have found that the UN Security Council tends to send peacekeepers to the civil conflicts where peace is hardest to establish and keep—that is, conflicts with more violence than average , where levels of mistrust are highest, and where poverty and poor governance make maintaining a stable peace least likely. Recent research has also found that UN peacekeepers are sent not just to active war zones but to the frontlines. This suggests that, if anything, current empirical studies have probably underestimated just how effective peacekeeping operations can be.

Peacekeeping is also inexpensive. The United States has spent over $2.1 trillion on overseas contingency operations and Department of Defense appropriations since September 11. By contrast, it allocated less than $1.5 billion to the UN’s peacekeeping budget in 2021—one-fourth of what New York City spends on its police department per year. Imagine what the UN could do if it had more funding and the full support of its member states. A major academic study in 2019 calculated that between 2001 and 2013, the UN could have significantly cut violence in four to five major conflicts if the world had spent more on peacekeeping and provided existing operations with stronger mandates.

Peacekeeping is remarkably inexpensive.

Peacekeeping does not always work as efficiently and successfully as it could. There are many well-known cases where UN missions failed, and certain ongoing operations, including those in the Central African Republic and Mali, are not going well. Sexual exploitation and abuse are thankfully uncommon during operations, but they still happen and are very alarming. Several new studies have also explored the unintended consequences of peacekeeping. Missions, for instance, can distort local economies, reproduce class and racial hierarchies, and raise the odds that women will engage in transactional sex. And even when it is done right, peacekeeping is not a panacea. It has not been shown to have a strong effect on establishing democracy, and it does not guarantee that wars will end. But the overriding conclusion from the most up-to-date studies is that peacekeeping missions play an enormous role in reducing violence and preventing conflicts from spreading.

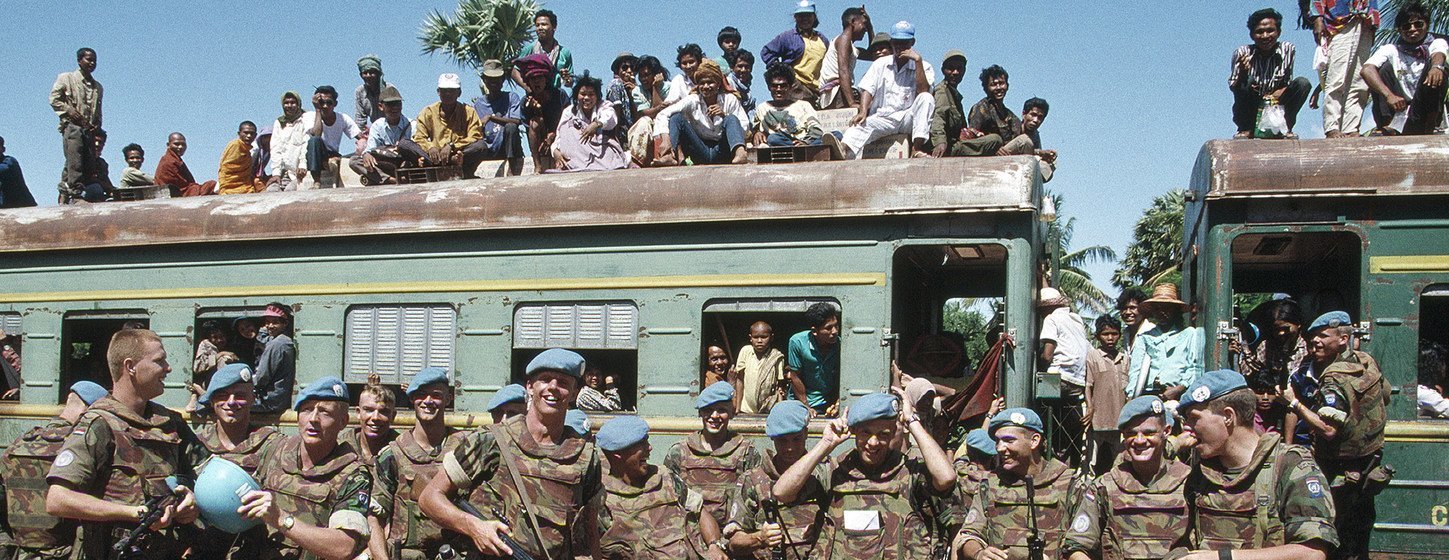

One doesn’t need to be a political scientist or a statistician to appreciate this fact. Even a cursory glance at peacekeeping’s record shows that missions are remarkably productive. Since the end of the Cold War, the UN has attempted to end 16 civil wars by deploying complex peacekeeping missions. Of those 16 missions, 11 successfully executed on their mandates, and none of the 11 countries has returned to civil war. The general public tends to vividly remember failed missions—such as when peacekeepers brought cholera to Haiti—but although those cases are horrific and tragic, they are not the norm. Success stories, such as those in Cambodia, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Liberia, Namibia, and Timor-Leste, are less newsworthy but more typical. In each of these cases, peacekeepers helped stabilize a state torn apart by violence, stayed as leaders transitioned to nonviolent politics, and then departed. Today, none of these countries are perfect democracies, but they are not locked in civil war.

Sierra Leone provides a case in point. The country’s brutal civil conflict ended after UN peacekeepers were sent from 1999 to 2005 to help implement a negotiated peace agreement. The UN’s “blue helmets” helped disarm 75,000 combatants, bringing stability to the formerly war-torn country. Timor-Leste is another good example. The country’s first elections brought mass violence during which 70 percent of the country’s physical infrastructure was destroyed, including the entire electric grid and almost all homes. Hundreds were killed, and more than half the population was forced to flee. Then, in 1999, United Nations peacekeepers arrived and began administering the territory. The UN returned the country to governmental control in 2002, but peacekeepers stayed for another decade before departing. During the United Nations’ back-to-back interventions, Timor-Leste’s Human Development Index score (which includes life expectancy, education, and per capita income) increased by more than 25 percent . The country remains at peace today.

SAFEKEEPING PEACEKEEPING

At least one country appears to understand the power of peacekeeping: China. As Washington has retreated from the global peacekeeping stage, Beijing has stepped into the void, becoming the second-largest financial contributor and the largest troop contributor to peacekeeping efforts among the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. This shift does not bode well for the future of democracy or for human rights promotion. Moments of conflict and instability are opportunities to shape countries’ political landscapes, and China knows that it can use peacekeeping missions to help determine the kinds and compositions of governments that assume power when conflicts end. Beijing also knows that peacekeeping itself can be weaponized to promote national interests . In 1999, China used its Security Council vote to force peacekeepers out of Macedonia after the country offered diplomatic recognition to Taiwan. Once the UN left, the country descended into civil war. (It was eventually stabilized by NATO.) Given Beijing’s behavior , the United States must ask itself if it really wants to cede leadership over this important tool.

If U.S. policymakers decide to ensure that peacekeeping receives proper funding and democratic support—and they should—then Washington must take several critical steps. First and foremost, the United States needs to pay what it owes. As the largest funder of the UN’s Department of Peace Operations, the U.S. government plays an important leadership role in authorizing and shaping UN missions. To convince other countries to contribute financially, the United States needs to set a better example by paying its own assessed dues.

Beijing has weaponized peacekeeping to promote its interests.

Second, the United States must convince the other four permanent members of the UN Security Council—China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom—to work together on peacekeeping. These powers are sometimes tempted to use missions as a means to advance their own strategic priorities. But they all have a shared interest in stopping civil wars, which breed extremism and terrorism and fuel refugee crises. They must find common ground on peacekeeping, especially during a time of rising interstate competition. They cannot let the kind of rivalry that impeded peacekeeping throughout the Cold War become an insurmountable barrier to using this effective instrument today.

Finally, the United States, along with other UN member states, should use what it knows about successful peacekeeping to make operations even more effective. That means countries must invest in preventive missions rather than authorizing deployments only after violence has broken out, as is currently typical . Member states should promptly respond when asked by the United Nations to provide critical armed capabilities, such as police units, but also when asked to provide unarmed resources—including field hospitals, monitors, mediation teams, and female personnel. As our own research has shown, the political and economic levers of peacekeeping are at least as effective, if not more so, than brute military strength. The presence of peacekeeping monitors, for example, can reduce the risk that armed groups will conduct surprise attacks, make it easier for aid to reach conflict zones, increase diplomatic support for peace, and often influence domestic opinion by making residents more supportive of nonviolent discourse. Peacekeepers can also help belligerents communicate with one another and help moderate disputes before they escalate.

After decades of counterinsurgencies, Americans are wary of military commitments abroad. The United States, after all, has not had a lot of success in ending many of the conflicts in which it has intervened. That said, the number of civil wars around the planet is increasing, and like it or not, the international community will need to become more engaged in trying to stop internecine conflicts. Thankfully, in United Nations peacekeeping, leaders have a collaborative and cost-effective tool they can deploy to resolve these conflicts and protect civilians. But to meet the world’s needs, U.S. policymakers have to provide the UN with more support and funding. That means they—and the people they represent—must first understand just how valuable peacekeeping has been.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to foreign affairs to get unlimited access..

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and over a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print and online, plus audio articles

- BARBARA F. WALTER is Rohr Professor of International Affairs at the School of Global Policy & Strategy at the University of California, San Diego. She is the author of How Civil Wars Start, and How to Stop Them .

- LISE MORJÉ HOWARD is Professor of Government and Foreign Service at Georgetown University and President of the Academic Council on the United Nations System. She is the author of Power in Peacekeeping .

- V. PAGE FORTNA is Harold Brown Professor of U.S. Foreign and Security Policy in the Political Science Department at Columbia University. She is the author of Does Peacekeeping Work? Shaping Belligerents’ Choices After Civil War .

- More By Barbara F. Walter

- More By Lise Morjé Howard

- More By V. Page Fortna

Most-Read Articles

Reagan didn’t win the cold war.

How a Myth About the Collapse of the Soviet Union Leads Republicans Astray on China

Ukraine’s Gamble

The Risks and Rewards of the Offensive Into Russia’s Kursk Region

Michael Kofman and Rob Lee

America is losing southeast asia.

Why U.S. Allies in the Region Are Turning Toward China

Planning for a Post-American NATO

Europe Must Prepare for a Second Trump Term

Phillips P. O’Brien and Edward Stringer

Recommended articles, the last days of intervention.

Afghanistan and the Delusions of Maximalism

Rory Stewart

Go your own way.

Why Rising Separatism Might Lead to More Conflict

Tanisha M. Fazal

What Is Peacekeeping?

In this free resource on the successes and failures of peacekeeping, learn about the UN missions tasked with transitioning countries out of war.

Peacekeeper troops deployed in the UN Interim Security Force for Abyei patrol Abeyi state, a disputed territory between Sudan and South Sudan.

Source: Albert Gonzalez Farran/AFP via Getty Images.

The world lacks a global police force capable of stopping violence in its tracks. However, it does have UN peacekeepers, who can help wind down conflicts and prevent them from recurring.

Take the case of El Salvador. Amid endemic inequality, repression, and political violence, the country descended into civil war in 1980. The conflict consumed the Central American nation for more than a decade. During the civil war, at least seventy-five thousand people were killed; a million more were displaced.

Despite the United Nations’ commitment to global peace and security, it refrained from direct intervention. This was due to the organization’s abiding respect for sovereignty —the principle that countries get to control what happens within their borders. As a result, the United Nations did not involve itself in El Salvador’s internal affairs.

The United Nations only interceded in 1991, after the Salvadoran government and the opposing insurgent group appealed for outside support to end the fighting. With both parties’ consent, the United Nations deployed a multinational force that helped monitor a cease-fire . Additionally, this force investigated war crimes and oversaw reforms of the country’s governing institutions. The United Nations later celebrated its peacekeeping mission. El Salvador transformed “from a country riven by conflict into a democratic and peaceful nation.”

Peacekeeping is not the same as peacemaking—much less warfighting. As the El Salvador mission illustrates, the United Nations struggles to prevent violence when wars are raging. However, the organization can help countries transition out of conflict when there is a peace to keep.

In this resource, we’ll explore peacekeeping operations, examining both their effectiveness and significant limitations.

Peacekeeping definition

Wars can technically end when fighting stops, but that doesn’t necessarily mean countries have achieved either peace or stability. In the aftermath of conflict, countries often experience economic dysfunction and mass displacement. Moreover, a deep sense of mistrust among former combatants is likely to exist. As a result, peace can easily backslide into violence, a phenomenon known as recidivism. Indeed, 60 percent [PDF] of intrastate conflicts in the early 2000s relapsed within five years.

UN peacekeepers can help countries avoid recidivism by promoting the rule of law , monitoring elections, and reintegrating fighters into society, among other functions. They accomplish those goals not just with a military or police presence but also by providing advisors, including economists, humanitarian workers, governance specialists, and legal experts.

For the United Nations to deploy a peacekeeping operation, it must clear two hurdles: First, it must have the warring parties’ consent.This condition is often difficult to achieve when governments do not want others interfering in their internal affairs. (However, sometimes both sides of a conflict embrace UN support as a way of advancing their legitimacy. Parties will also embrace UN involvement to secure a prominent seat at the negotiating table.) Second, the operation must be approved by the UN Security Council (UNSC). Overcoming this hurdle requires passing a vote by the fifteen-member body without a single veto from one of its five permanent members (the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom).

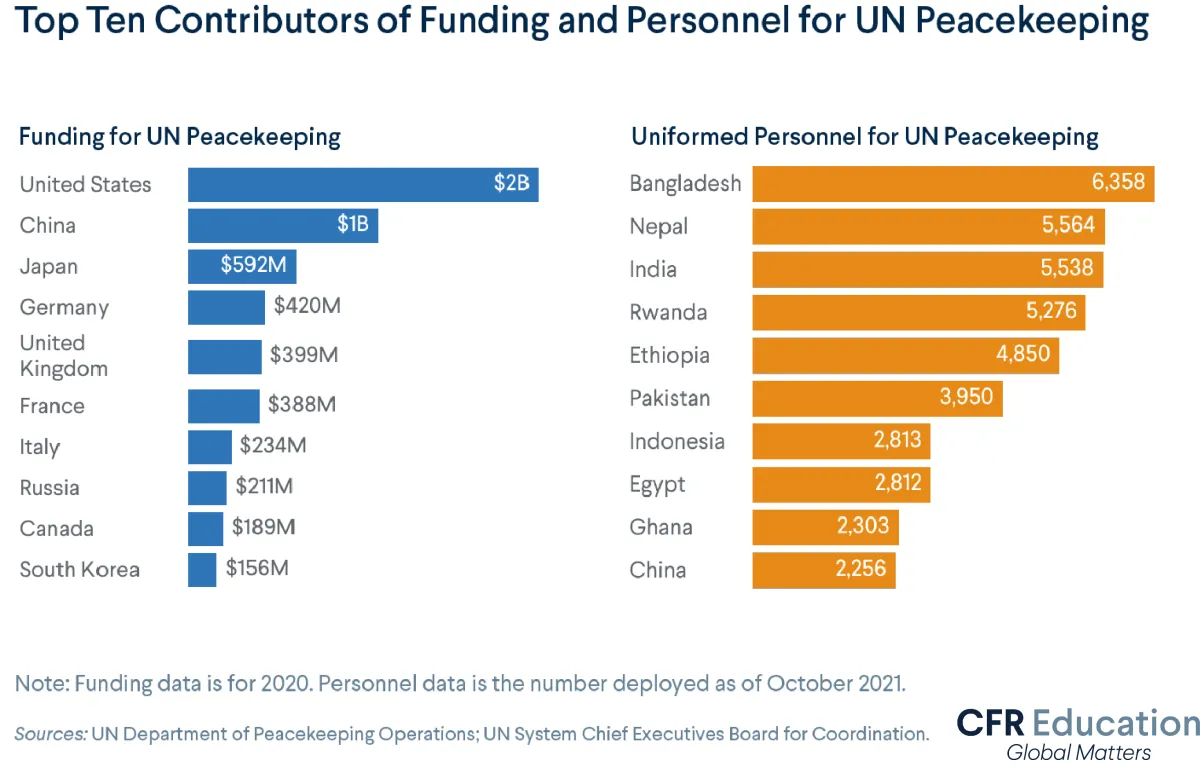

If an operation is approved, the UN General Assembly splits up the financing and equipping costs among UN member states assessed according to UN rules. As of 2021, the United States, China, and Japan contributed the most toward funding peacekeeping missions . Meanwhile, Bangladesh, Nepal, and India provided (at each country’s discretion) the greatest number of military and police forces [PDF] for UN missions.

Source: UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations; UN System Chief Executives Board for Coordination.

UN peacekeeping missions

Since the organization’s founding in 1945, the United Nations has deployed more than one million peacekeepers from over 120 countries on more than 70 missions worldwide.

Guiding each mission is a specific mandate set by the UN Security Council. The directives range from limited ones, such as ceasefire monitoring, to broad and ambitious undertakings, like overhauling a national government. The mandate also dictates a mission’s size, which varies from a few hundred specialists to tens of thousands of peacekeeping troops.

The UN operation in El Salvador—which consisted of military, police, and civilian officers from seventeen countries—combined many different elements of peacekeeping. The operation supervised peace agreements between the Salvadoran government and a leftist insurgent group. Peacekeepers also oversaw amnesty guarantees and disarmament programs, like clearing over four hundred minefields throughout the country. Additionally, the mission supervised major overhauls to El Salvador’s electoral, judicial, military, and police institutions. Those efforts included training judges and court officials and developing curricula for military academies that emphasized human rights. Finally, peacekeepers established a commission to document the war’s atrocities. This documentation came in the hopes that an honest accounting would help facilitate reconciliation. The operation officially ended in 1995 and is generally regarded as a qualified success. Despite the end of the political conflict and the establishment of democratic processes, El Salvador today remains one of the world’s most violent countries.

FMLN rebel guerrillas line up along a road in the conflictive zone of Chalatenango to welcome the first United Nations observers in the rebel controlled area, in San Jose Las Flores, El Salvador, Aug. 30, 1991.

Source: AP Photo/Luis Romero

As of December 2021, the United Nations operates twelve peacekeeping missions around the world. Six of those missions are located in Africa, where more than fifty thousand troops facilitate UN operations. Tens of thousands more operate peacekeeping or security missions under the auspices of the African Union , European Union , and other regional blocs.

What are the challenges for peacekeeping?

When the proper conditions exist, peacekeeping operations can lessen the severity of fighting and help countries emerge from conflict. Some experts suggest UN operations lead to shorter wars and fewer civilian deaths.

But, peacekeeping operations face numerous hurdles and limitations that undermine their effectiveness:

Consent requirement: The United Nations can only authorize peacekeeping operations with permission from the warring parties. In the absence of such consent—especially common when governments are the ones perpetrating the violence—civilians suffer while the United Nations is sidelined. The Syrian government, for instance, has expressed no interest in allowing the United Nations to intervene in the country’s ongoing, decade-long civil war .

Consent can also be withdrawn. When Egypt began preparing to go to war with Israel in 1967, the Egyptian government demanded that UN peacekeepers leave the country. Although war was clearly imminent, the peacekeepers had no option but to comply. If the UN had remained in Egypt without the government’s consent, they would be violating Egyptian sovereignty . As feared, war erupted between Egypt and Israel less than one month later.

Failure to protect civilians: Commitments to non-aggression and an inability to react to changing circumstances that fall outside their mandate can also hinder peacekeeping operations. In 2014, UN investigators found [PDF] that peacekeepers only responded to one in five cases in which civilians were threatened. Perhaps most infamously, UN peacekeepers monitoring local elections in Rwanda in 1994 were repeatedly ordered not to intervene as simmering ethnic tensions erupted into genocide . Peacekeepers were urged to stand down so as not to interfere in a domestic conflict and overstep the narrow scope of their mission. However, as UN peacekeepers stood on the sidelines, more than eight hundred thousand Rwandans were killed in just three months.

Rwandan refugees walk on the Byumba road as they flee from Kigali on May 11, 1994.

Source: GERARD JULIEN/AFP via Getty Images

Such failures led to UN members endorsing in 2005 what became known as the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine. This principle states that countries have a fundamental sovereign responsibility to protect their citizens from genocide , crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing. If they fail to do so, that responsibility falls to the United Nations system, particularly the UN Security Council, which may take steps to protect those vulnerable people. Under such conditions, the United Nations can violate the sovereignty of the relevant country if needed. In other words, countries acting under UN auspices can use all means necessary—including military intervention—to prevent large-scale loss of life or displacement. The R2P doctrine was put to the test in 2011 amid Libya’s civil war . But the destabilizing effects of that humanitarian intervention and its evolution into a regime-change operation have made countries that were already wary of R2P, such as China and Russia, unlikely to green-light future humanitarian interventions.

To learn more about R2P, check out The Rise and Fall of the Responsibility to Protect .

Record of misconduct: Peacekeepers have repeatedly been accused of human rights violations, including sexual abuse. In the early 2000s, reports of UN personnel committing sexual violence plagued the United Nations’ efforts to conduct political stabilization, disarmament , and police reform in Haiti. In 2021, the United Nations withdrew 450 peacekeepers from the Central African Republic, following similar sexual abuse allegations. Although the United Nations has increasingly investigated such reports, none has led to a public conviction. (UN peacekeepers are heavily shielded from prosecution in the countries where they serve). UN peacekeepers have also been accused of corrupt practices—such as bribery and extortion—and gross misconduct. For example, peacekeepers were likely the source of a deadly cholera outbreak in 2010 that killed thousands of Haitians.

Budget constraints: In 2019, more than one hundred thousand peacekeepers were active in fourteen countries, constituting the second-largest military force deployed abroad, trailing only that of the United States. However, UN peacekeeping operates on a limited budget, accounting for less than 0.5 percent of global military expenditures in the 2021 fiscal year. With ambitious mandates and severe financial constraints, peacekeeping missions often struggle to fulfill their goals. For example, fewer than eighteen thousand UN personnel are tasked with protecting civilians in the Democratic Republic of Congo—a sprawling, mountainous country of ninety million people.

Peacekeeping: an imperfect tool

Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan once said that UN peacekeeping is “the only fire brigade in the world that has to wait for the fire to break out before it can acquire a fire engine.” Indeed, the United Nations has no standing peacekeeping force; every operation must be established on an ad hoc basis. This reality compounds peacekeeping’s already significant challenges. As a result, peacekeeping is a largely ineffective foreign policy tool for stopping violence when war is raging.

However, proponents maintain that when the conditions for peace exist, peacekeeping can help shorten wars, protect civilians, and keep temperatures cool in the aftermath of conflicts.

Now that this resource has covered the fundamentals of peacekeeping, put these principles into practice with CFR Education’s companion mini simulation on Peacekeeping .

- UN Peacekeeping: A Force for Global Peace and Stability

- Introduction

- The United States and the United Nations: A Critical Partnership to Tackle Global Challenges

- How the UN Advances U.S. Economic Interests

- American Attitudes Toward the UN

- Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Providing Humanitarian Assistance

- Stopping the Climate Emergency

- Global Health

- The Global Goals: Ending Extreme Poverty

- UN Political Missions

- The UN and Human Rights

- The UN Budget

- U.S. Financial Contributions to the UN

- UN Strengthening and Reform

- Key UN Institutions

- UN Funds, Programs and Specialized Agencies

For more than seven decades, UN peacekeeping has been one of the most important tools the UN has at its disposal for conflict mitigation and stabilization.

Helping countries navigate the difficult path from conflict to peace, peacekeeping has unique strengths , including high levels of international legitimacy and an ability to deploy and sustain troops and police from around the globe, integrating them with civilian peacekeepers to advance multidimensional mandates. Today’s peacekeeping operations are called upon not only to stabilize conflict zones and separate warring parties, but also to protect civilians, assist in the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of former combatants, support the organization of elections, protect and promote human rights, and assist in restoring the rule of law.

The U.S. has long advocated for the broadening of the size and scope of UN peacekeeping missions, using its position as a permanent member of the Security Council to push for mandates that more closely reflect current challenges. Both Republican and Democratic presidents have recognized the value of UN peacekeeping, because:

- Peacekeeping Is Effective : A November 2021 Foreign Affairs article titled the “ Astonishing Success of Peacekeeping ” explains that “Decades of academic research has demonstrated that UN peacekeeping not only works at stopping conflicts but works better than anything else experts know. Peacekeeping is effective at resolving civil wars, reducing violence during wars, preventing wars from recurring, and rebuilding state institutions. It succeeds at protecting civilian lives and reducing sexual and gender-based violence. The piece also notes that “To convince other countries to contribute financially, the United States needs to set a better example by paying its own assessed dues.”¹

- UN Missions Cost Less than Other Forms of Military Intervention : Two studies published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office more than a decade apart (in 2006² and 2018³) found that a UN operation is one-eighth the cost to American taxpayers of deploying a comparable U.S. force. Overall, at a yearly cost of approximately $6.5 billion, UN peacekeeping is one half of the state of Rhode Island’s annual budget.

- Promotes Multilateral Burden-Sharing : The UN has no standing army, and therefore depends on Member States to voluntarily contribute troops and police to its peacekeeping operations. While the U.S., as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, plays a central role in the decision to deploy peacekeeping missions, it provides very few uniformed personnel: currently just several dozen out of 73,000 total uniformed personnel. A range of U.S. partners and allies—including India, Rwanda, Tanzania, Jordan, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Nepal—provide the bulk of the rest.

Barbara F. Walter, Lise Morjé Howard, V. Page Fortna. “The Astonishing Success of Peacekeeping”. Foreign Policy. November 29, 2021. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2021-11-29/astonishing-success-peacekeeping

“cost comparison of actual un and hypothetical u.s. operations in haiti.” government accountability office gao-06-331., “un peacekeeping cost estimate for hypothetical u.s. operation exceeds actual costs for comparable un operation,” government accountability office gao-18-243., key un peacekeeping missions in the field.

The United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) was established in 1964 to end fighting between Greek and Turkish Cypriots on the island and bring about a return to normal conditions. The mission’s responsibilities expanded in 1974, following a coup d’état by elements favoring union with Greece and a subsequent military intervention by Turkey. Since a de facto ceasefire in 1974, UNFICYP has supervised the ceasefire lines, provided humanitarian assistance, and maintained a buffer zone between Turkish forces in the north and the Greek Cypriot forces in the south.

While UNFICYP has successfully prevented major hostilities between Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities over the last several decades, recent political developments make this an incredibly important time for the UN’s work. During peace talks in April 2021, Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar formally proposed a two-state solution to the island’s conflict, which had immediate negative ramifications, endangering the prospects for a bizonal, bicommunal federation that has long been supported by the UN Security Council. Then, in July 2021, Turkish Cypriot authorities announced plans to revert a section of Varosha, an area from which Greek Cypriots were displaced due the Turkish invasion, from military to civilian control and open it for potential resettlement. This declaration led the UN Security Council to stress “the need to avoid any unilateral action that could trigger tensions on the island and undermine the prospects for a peaceful settlement.” Given the ongoing danger of renewed hostilities in the country, it is critical that UN peacekeepers continue to maintain a presence in Cyprus, both to guarantee peace and stability and to promote continued dialogue and negotiations between the two sides.

The UN Security Council voted to deploy UN peacekeepers to Mali in 2013, following a French military intervention targeting armed extremist groups linked to al-Qaeda that had taken over the country’s vast northern regions. Since then, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) has worked to prevent these organizations—now including a regional affiliate of ISIS—from extending their reach in the area or reoccupying towns in northern Mali that they were pushed out of. MINUSMA is also mandated to help extend state authority to these areas by training judges and supporting security sector reform. In addition to these security and governance-related tasks, MINUSMA works to protect civilians in its area of operations, facilitate distribution of humanitarian aid, and assist in the reintegration of people who have been displaced by violence.

Unfortunately, since 2020, Mali has suffered two military coups, and democratic elections have been repeatedly postponed. This has led to serious political instability and given extremist groups more room to maneuver. As a result, it will be critical for MINUSMA to maintain a strong presence in the country’s northern and central regions moving forward, in order to prevent a further deterioration of the security situation in those areas.

SOUTH SUDAN

The UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) was first deployed in 2011 when South Sudan gained independence, tasked with helping to stabilize the world’s newest country and support state-building efforts. Two years later, however, when civil war erupted between military factions supporting the President and Vice President, UNMISS was forced to shift its mission virtually over-night to civilian protection and opened the gates of its bases to fleeing civilians. This action saved the lives of more than 200,000 people across the country who otherwise could have been targeted or killed for their ethnicity or perceived political affiliations.

In 2018, the main parties to the conflict reached a peace agreement, and while implementation has been slow, threats facing civilians in the seven protection of civilians sites adjacent to UN bases have diminished considerably. As a result, UNMISS has handed control of a majority of the sites to the government and facilitated efforts by UN humanitarian agencies to continue providing essential services within them. Meanwhile, UNMISS has pivoted to focusing on protecting civilians from more localized subnational violence in the country and facilitating humanitarian assistance to more than 800,000 people displaced by the country’s worst flooding in 60 years.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- History and development

- Principles and membership

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- Economic and Social Council

- Trusteeship Council

- International Court of Justice

- Secretariat

- Subsidiary organs

- Specialized agencies

- Global conferences

- Privileges and immunities

- Headquarters

Peacekeeping, peacemaking, and peace building

Sanctions and military action.

- Arms control and disarmament

- Economic reconstruction

- Financing economic development

- Trade and development

- Human rights

- Control of narcotics

- Health and welfare issues

- The environment

- Dependent areas

- Development of international law

- United Nations members

- United Nations secretaries-general

- What was Eleanor Roosevelt’s childhood like?

- What were some of George H.W. Bush's achievements?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Geneva International Centre for Justice - United Nations Day - 24 October

- Jewish Virtual Library - United Nations: The United States and the Founding of the United Nations

- The Balance - The United Nations and How it Works

- Official Site of the United Nations

- United Nations - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- United Nations - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

International armed forces were first used in 1948 to observe cease-fires in Kashmir and Palestine . Although not specifically mentioned in the UN Charter, the use of such forces as a buffer between warring parties pending troop withdrawals and negotiations—a practice known as peacekeeping—was formalized in 1956 during the Suez Crisis between Egypt , Israel , France , and the United Kingdom . Peacekeeping missions have taken many forms, though they have in common the fact that they are designed to be peaceful, that they involve military troops from several countries, and that the troops serve under the authority of the UN Security Council. In 1988 the UN Peacekeeping Forces were awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace.

Recent News

During the Cold War , so-called first-generation, or “classic,” peacekeeping was used in conflicts in the Middle East and Africa and in conflicts stemming from decolonization in Asia . Between 1948 and 1988 the UN undertook 13 peacekeeping missions involving generally lightly armed troops from neutral countries other than the permanent members of the Security Council—most often Canada , Sweden , Norway , Finland , India , Ireland , and Italy . Troops in these missions, the so-called “ Blue Helmets,” were allowed to use force only in self-defense. The missions were given and enjoyed the consent of the parties to the conflict and the support of the Security Council and the troop-contributing countries.

With the end of the Cold War, the challenges of peacekeeping became more complex. In order to respond to situations in which internal order had broken down and the civilian population was suffering, “second-generation” peacekeeping was developed to achieve multiple political and social objectives. Unlike first-generation peacekeeping, second-generation peacekeeping often involves civilian experts and relief specialists as well as soldiers. Another difference between second-generation and first-generation peacekeeping is that soldiers in some second-generation missions are authorized to employ force for reasons other than self-defense. Because the goals of second-generation peacekeeping can be variable and difficult to define, however, much controversy has accompanied the use of troops in such missions.

In the 1990s, second-generation peacekeeping missions were undertaken in Cambodia (1991–93), the former Yugoslavia (1992–95), Somalia (1992–95), and elsewhere and included troops from the permanent members of the Security Council as well as from the developed and developing world (e.g., Australia , Pakistan , Ghana , Nigeria , Fiji , India ). In the former Yugoslav province of Bosnia and Herzegovina , the Security Council created “safe areas” to protect the predominantly Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) population from Serbian attacks, and UN troops were authorized to defend the areas with force. In each of these cases, the UN reacted to threats to peace and security within states, sometimes taking sides in domestic disputes and thus jeopardizing its own neutrality. Between 1988 and 2000 more than 30 peacekeeping efforts were authorized, and at their peak in 1993 more than 80,000 peacekeeping troops representing 77 countries were deployed on missions throughout the world. In the first years of the 21st century, annual UN expenditures on peacekeeping operations exceeded $2 billion.

In addition to traditional peacekeeping and preventive diplomacy, in the post-Cold War era the functions of UN forces were expanded considerably to include peacemaking and peace building. (Former UN secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali described these additional functions in his reports An Agenda for Peace [1992] and Supplement to an Agenda for Peace [1995].) For example, since 1990 UN forces have supervised elections in many parts of the world, including Nicaragua , Eritrea , and Cambodia; encouraged peace negotiations in El Salvador , Angola , and Western Sahara ; and distributed food in Somalia . The presence of UN troops in Yugoslavia during the violent and protracted disintegration of that country renewed discussion about the role of UN troops in refugee resettlement. In 1992 the UN created the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO), which provides administrative and technical support for political and humanitarian missions and coordinates all mine-clearing activities conducted under UN auspices .

The UN’s peacekeeping, peacemaking, and peace-building activities have suffered from serious logistical and financial difficulties. As more missions are undertaken, the costs and controversies associated with them have multiplied dramatically. Although the UN reimburses countries for the use of equipment, these payments have been limited because of the failure of many member states to pay their UN dues.

By subscribing to the Charter, all members undertake to place at the disposal of the Security Council armed forces and facilities for military sanctions against aggressors or disturbers of the peace. During the Cold War, however, no agreements to give this measure effect were concluded. Following the end of the Cold War, the possibility of creating permanent UN forces was revived.

During the Cold War the provisions of chapter 7 of the UN Charter were invoked only twice with the support of all five permanent Security Council members—against Southern Rhodesia in 1966 and against South Africa in 1977. After fighting broke out between North and South Korea in June 1950, the United States obtained a Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force to support its ally, South Korea, and turn back North Korean forces. Because the Soviet Union was at the time boycotting the Security Council over its refusal to seat the People’s Republic of China , there was no veto of the U.S. measure. As a result, a U.S.-led multinational force fought under the UN banner until a cease-fire was reached on July 27, 1953.

The Security Council again voted to use UN armed forces to repel an aggressor following the August 1990 invasion of Kuwait by Iraq . After condemning the aggression and imposing economic sanctions on Iraq, the council authorized member states to use “all necessary means” to restore “peace and security” to Kuwait. The resulting Persian Gulf War lasted six weeks, until Iraq agreed to comply with UN resolutions and withdraw from Kuwait. The UN continued to monitor Iraq’s compliance with its resolutions, which included the demand that Iraq eliminate its weapons of mass destruction . In accordance with this resolution, the Security Council established a UN Special Mission (UNSCOM) to inspect and verify Iraq’s implementation of the cease-fire terms. The United States, however, continued to bomb Iraqi weapons installations from time to time, citing Iraqi violations of “no-fly” zones in the northern and southern regions of the country, the targeting of U.S. military aircraft by Iraqi radar, and the obstruction of inspection efforts undertaken by UNSCOM .

The preponderant role of the United States in initiating and commanding UN actions in Korea in 1950 and the Persian Gulf in 1990–91 prompted debate over whether the requirements and spirit of collective security could ever be achieved apart from the interests of the most powerful countries and without U.S. control. The continued U.S. bombing of Iraq subsequent to the Gulf War created further controversy about whether the raids were justified under previous UN Security Council resolutions and, more generally, about whether the United States was entitled to undertake military actions in the name of collective security without the explicit approval and cooperation of the UN. Meanwhile some military personnel and members of the U.S. Congress opposed the practice of allowing U.S. troops to serve under UN command, arguing that it amounted to an infringement of national sovereignty . Still others in the United States and western Europe urged a closer integration of United States and allied command structures in UN military operations.

In order to assess the UN’s expanded role in ensuring international peace and security through dispute settlement, peacekeeping, peace building, and enforcement action, a comprehensive review of UN Peace Operations was undertaken. The resulting Brahimi Report (formally the Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations), issued in 2000, outlined the need for strengthening the UN’s capacity to undertake a wide variety of missions. Among the many recommendations of the report was that the UN maintain brigade-size forces of 5,000 troops that would be ready to deploy in 30 to 90 days and that UN headquarters be staffed with trained military professionals able to use advanced information technologies and to plan operations with a UN team including political, development, and human rights experts.

Does UN Peacekeeping work? Here’s what the data says

Facebook Twitter Print Email

Failures on the part of UN Peacekeeping missions have been highly publicised and well documented – and rightly so. But if you look at the overall picture and crunch the data, a different and ultimately positive picture emerges.

The evidence, collected in 16 peer-reviewed studies, shows that peacekeepers – or ‘blue helmets’ as the moniker goes - significantly reduce civilian casualties, shorten conflicts, and help make peace agreements stick.

In fact, the majority of UN Peacekeeping missions succeed in their primary goal, ultimately stabilizing societies and ending war.