The “new normal” in US-China relations: Hardening competition and deep interdependence

Subscribe to the china bulletin, ryan hass ryan hass senior fellow - foreign policy , center for asia policy studies , john l. thornton china center , chen-fu and cecilia yen koo chair in taiwan studies, the michael h. armacost chair.

August 12, 2021

The intensification of U.S.-China competition has captured significant attention in recent years. American attitudes toward China have become more negative during this period, as anger has built over disruptions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, Beijing’s trampling of Hong Kong’s autonomy, human rights violations in Xinjiang, and job losses to China.

Amidst this focus on great power competition, two broader trends in the U.S.-China relationship have commanded relatively less attention. The first has been the widening gap in America’s and China’s overall national power relative to every other country in the world. The second has been the continuing thick interdependence between the United States and China, even amidst their growing rivalry. Even on economic issues, where rhetoric and actions around decoupling command the most attention, trade and investment data continue to point stubbornly in the direction of deep interdependence. These trends will impact how competition is conducted between the U.S. and China in the coming years.

Separating from the pack

As America’s unipolarity in the international system has waned, there has been renewed focus on the role of major powers in the international system, including the European Union, Russia, India, and Japan. Each of these powers has a major population and substantial economic weight or military heft, but as my Brookings colleague Bruce Jones has observed , none have all. Only the United States and China possess all these attributes.

The U.S. and China are likely to continue amassing disproportionate weight in the international system going forward. Their growing role in the global economy is fueled largely by both countries’ technology sectors . These two countries have unique traits. These include world-class research expertise, deep capital pools, data abundance, and highly competitive innovation ecosystems. Both are benefitting disproportionately from a clustering effect around technology hubs. For example, of the roughly 4,500 artificial intelligence-involved companies in the world, about half operate in the U.S. and one-third operate in China. According to a widely cited study by PricewaterhouseCoopers, the U.S. and China are set to capture 70% of the $15.7 trillion windfall that AI is expected to add to the global economy by 2030.

The United States and China have been reinvesting their economic gains to varying degrees into research and development for new and emerging technologies that will continue to propel them forward. While it is not foregone that the U.S. and China will remain at the frontier of innovation indefinitely, it also is not clear which other countries might displace them or on what timeline. Overall, China’s economy likely will cool in the coming years relative to its blistering pace of growth in recent decades, but it is not likely to collapse.

Deep interdependence

At the same time, bilateral competition between the United States and China also is intensifying. Even so, rising bilateral friction has not – at least not yet – undone the deep interdependencies that have built up between the two powers over decades.

In the economic realm, trade and investment ties remain significant, even as both countries continue to take steps to limit vulnerabilities from the other. For example, Chinese regulators have been asserting greater control over when and where Chinese companies raise capital; Beijing’s recent probe of ride-hailing app Didi Chuxing provides but the latest example. China’s top leaders have been emphasizing the need for greater technology “self-sufficiency” and have been pouring billions of dollars of state capital into this drive. Meanwhile, U.S. officials have been seeking to limit American investments from going to Chinese companies linked to the military or surveillance sectors. The Security and Exchange Commission’s scrutiny of initial public offerings for Chinese companies and its focus on ensuring Chinese companies meet American accounting standards could result in some currently listed Chinese companies being removed from U.S. exchanges. Both countries have sought to disentangle supply chains around sensitive technologies with national security, and in the American case, human rights dimensions. U.S. officials have sought to raise awareness of the risks for American firms of doing business in Hong Kong and Xinjiang .

Even so, U.S.-China trade and investment ties remain robust. In 2020, China was America’s largest goods trading partner, third largest export market, and largest source of imports. Exports to China supported an estimated 1.2 million jobs in the United States in 2019. Most U.S. companies operating in China report being committed to the China market for the long term.

Related Books

March 9, 2021

Tarun Chhabra, Rush Doshi, Ryan Hass, Emilie Kimball

June 22, 2021

May 11, 2021

U.S. investment firms have been increasing their positions in China, following a global trend . BlackRock , J.P. Morgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley have all increased their exposure in China, matching similar efforts by UBS , Nomura Holdings , Credit Suisse , and AXA . The Rhodium Group estimates that U.S. investors held $1.1 trillion in equities issued by Chinese companies, and that there was as much as $3.3 trillion in U.S.-China two-way equity and bond holdings at the end of 2020.

One leg of the U.S.-China economic relationship that has atrophied in recent years has been China’s flow of investment into the United States. This has largely been a product of tightened capital controls in China, growing Chinese government scrutiny of its companies’ offshore investments, and enhanced U.S. screening of Chinese investments for national security concerns.

Another area of U.S.-China interdependence has been knowledge production. As U.S.-China technology expert Matt Sheehan has observed , “With the rise of Chinese talent and capital, the exchange of technological know-how between the United States and China now takes place among private businesses and between individuals.” Leading technology companies in both countries have been building research centers in the other. Alibaba , Baidu , and Tencent have all opened research centers in the United States, just as Apple , Microsoft , Tesla , and other major American technology companies rely upon engineering talent in China.

In science collaboration, The Nature Index ranks the joint research between the two countries as the world’s most academically fertile. U.S.-China scientific collaboration grew by more than 10% each year on average between 2015 and 2019. Even following the global spread of COVID-19, American and Chinese experts collaborated more during the past year than over the previous five years combined . This has led to over 100 co-authored articles in leading scientific journals and frequent joint appearances in science-focused workshops and webinars.

China also is the largest source of international students in the United States. In the 2019-20 year, there were over 370,000 Chinese students in the U.S., representing 34% of international students in colleges and universities. Up until now, many of the top Chinese students have stayed in the United States following graduation and contributed to America’s scientific, technological, and economic development. It remains to be seen whether this trend will continue.

Competitive interdependence

The scale of American and Chinese interests implicated will likely induce sobriety over time in Washington and Beijing as to how the relationship is managed. The U.S. policy focus for the foreseeable future is not likely to be seeking to “defeat” China or compel the collapse of the Chinese Communist Party. Rather, the focus will be on taking steps at home and with partners abroad to strengthen America’s long-term competitiveness vis-à-vis China. At the same time, American leaders will continue to push their Chinese counterparts to improve the treatment of their citizens. Such efforts are definitional to America’s self-identity as a champion of values.

The dense webs formed by trade, financial, scientific, and academic links between the United States and China will make it difficult for one side to inflict harm on the other without hurting itself in the process. As Joe Nye has written , “America can decouple security risks like Huawei from its 5G telecommunications network, but trying to curtail all trade with China would be too costly. And even if breaking apart economic interdependence were possible, we cannot decouple the ecological interdependence that obeys the laws of biology and physics, not politics.”

President Joe Biden likely will use the challenges posed by China as a spur for his domestic resilience agenda. He is not an ideologue, though, and is unlikely to limit his own flexibility by painting the world with permanent black and white dividing lines. The Biden team knows it will be harder to realize progress on serious global challenges like climate change, pandemics, and inclusive global economic recovery without pragmatic dealings with non-democratic states.

Major near-term improvements to the U.S.-China relationship are unlikely, barring an unexpected moderation in Beijing’s behavior. At the same time, the relationship is also unlikely to tip into outright hostility, barring an unforeseen dramatic event, such as a Chinese act of aggression against an American security partner.

U.S.-China relations are going to be hard-nosed and tense. Neither side is likely to offer concessions in service of smoother relations. At the same time, the balance of interests on both sides likely will control hostile impulses, placing the relationship in a state of hardening competition that coexists alongside a mutual awareness that both sides will be impacted — for good or ill — by their capacity to address common challenges.

Related Content

Ryan Hass, Emilie Kimball, Bill Finan

July 9, 2021

May 4, 2021

Ryan Hass, Jessica Chen Weiss

July 12, 2021

McCall Mintzer and Kevin Dong provided research and editing assistance on this piece.

U.S. Foreign Policy

Foreign Policy

China Hong Kong

Center for Asia Policy Studies John L. Thornton China Center

Mireya Solís, Mathieu Duchâtel

June 3, 2024

Mark MacCarthy

May 23, 2024

Online Only

9:30 am - 10:30 am EDT

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- Teaching Note

- HBS Case Collection

China: The New Normal

- Format: Print

- | Language: English

- | Pages: 19

About The Author

Richard H.K. Vietor

More from the author.

- Faculty Research

Deficits and Debt: The U.S. Current Account

Uruguay: south america's singapore.

- May 2023 (Revised July 2024)

America’s Budget Impasse, 2009–2023

- Deficits and Debt: The U.S. Current Account By: Laura Alfaro and Richard Vietor

- Uruguay: South America's Singapore? By: Richard Vietor

- America’s Budget Impasse, 2009–2023 By: Richard Vietor

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Proceedings of the 2nd Czech-China Scientific Conference 2016

China’s “New Normal” and Its Quality of Development

Reviewed: 09 November 2016 Published: 01 February 2017

DOI: 10.5772/66791

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Proceeding

Proceedings of the 2nd Czech-China Scientific Conference 2016

Edited by Jaromir Gottvald and Petr Praus

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

1,481 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

China’s new normal means a new higher stage of development, when an alternative is to improve the quality of economic development instead of accelerating growth rate by expansion policies. And the quality of development is the quality of living of most people. This study is to examine the current situations of China’s quality of development by comparing China’s human development index, inequality indices (Gini, quintile, and Palma), and development potential (human capital index) with the developed countries in Europe, North America, and Oceania, as well as countries with typical traits, such as the Latin American countries, Japan, and Czech Republic; further to put forward China’s policy focuses in the new normal stage according to the concluded research results.

- China’s new normal

- human development index (HDI)

- human capital index (HCI)

- quality of life

Author Information

- Faculty of Economics, Hebei GEO University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei, China

Haochen Guo

Mengnan zhang.

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. China’s new normal–a new higher stage

China’s new normal is original from the slowdown of the GDP growth rate in recent years. Graph 1 shows three obvious slowdowns since 1979. The three slowdowns are all accompanying with economic upheavals and big inflations, only the last and current one induces a new concept, “New Normal.”

Graph 1.

Per capita GDP growth China 1979–2014 (1978 constant). Data source: Chinese statistics yearbook 2015: 3–1, 3–5.

In May 2014, President Xi Jinping put forward the “new normal of China’s economy,” and described a series of new performances of China’s economy. On December 5, 2014, the Politburo meeting of the Communist Party of China formally advocated to “take the initiative to adapt to the economic development of the new normal.” Since then, the Chinese economy has entered a “new normal” stage.

Generally, the “new normal” has two characteristics: the first is about the slowdown from high-speed growth to high-middle-speed growth; the second is about the transformation of growth pattern from scale extensive growth to quality and intensive growth [ 1 ]. For the future strategy of Chinese government, there seem also two main streams: one is focusing on the growth speed, while thinking the transformation of growth pattern is given, for they think China need to sustain a growth speed to cross the middle-income trap that is the first priority of China [ 2 – 5 ]; another is to focus on the transformation of growth pattern and growth quality, while keeping the high-middle-speed growth even middle-speed growth [ 1 , 6 , 7 ]. We stand for the second view.

The speed slowdown of China’s economic growth is not a bad thing. First, the growth rate from the high-speed down to high-middle-speed is suitable for China. China’s GDP growth rate of 6.9% and per capita GDP growth rate of 6.3% in 2015, are still high enough in the context of the world (the world average of GDP growth rate is 2.5%, 2015). Second, the slowdown is beneficial from the consideration of the limit of natural resources and serious environmental problems of China, as the environment could no longer sustain the long lasting high-speed growth, even if it is further lower; after all, the ecological environment is the precondition of a country’s sustainable development. Third, as a common sense, high-speed growth is apt to bring economic upheaval, and destroy the stability of development. Hence, in long run, keeping a high-middle-speed is better than high-speed for the sake of stable sustainable development.

Moreover, the speed slowdown is a good signal that indicates China has been entering a new stage of development, when an alternative is to improve the quality of economic development instead of accelerating growth rate by expansion policies. And the quality of development is the quality of living of most people; i.e., we can pay more attentions to most people’s quality of life, as like a developed country’s performances.

In brief, China’s new normal means a new higher stage of development with the pursuit of a developed country. This study is to examine the current situations of China’s quality of development by comparing China’s human development index, inequality indices (Gini, quintile, and Palma), and development potential (human capital index) with the developed countries in Europe, North America, and Oceania, as well as countries with typical traits, such as the Latin American countries, Japan and Czech Republic; further to put forward China’s policy focuses in the new normal stage, so to catch up with the developed countries in quality of development.

2. Material and methods

For comparing the quality of development, we arrange here with representative countries, comparable indicators and methodologies.

2.1. Countries considered

China is a large developing country with the largest population and large land mass in the world, and with socialist nature as its Constitution expressed. The countries as comparing counterparts, we choose mainly concerning: (1) well developed (at least its HDI higher than China’s); (2) relative competent size of territory and population; and (3) representative in different regions and social models. By data testing, 14 countries have been selected as reference countries as follows.

The four countries, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland, are all Nordic countries, well developed with long-term stable sustainable qualified development, as generally accepted model of ideal society on the globe currently, the “Nordic model,” which have more socialist component, such as generous social welfare and equal opportunity for public services to each family and individual all over the country.

These two countries, Germany and Switzerland, are high developed market economies with more socialist-natures in the “Rhine model,” as major roles in mainland Europe with long-term stable qualified development and good performance in equality aspect.

The two countries, USA and UK, are well-developed market economies, natured as typical capitalist market in the “Anglo-Saxon model,” and once the super powers in different ages.

The country of Australia is on the Oceania, tightly related with China in commercial intercourse; well-developed capitalist economy with sound social welfare as well.

The country of Japan is the next neighbor of China, the first and most developed economy in Asia, and has good performance generally but in depression for a long time in recent years.

The country of Czech Republic is a former socialist country located in central-eastern Europe, with the history of a member of former Soviet Union alliance, and keeps the most equal society record; not well developed but with very high value of human development index (Rank 28 in 2014 in nearly 200 countries).

The three countries, Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil, are also developing countries but capitalist natured in Latin America, ranking forefront of the world in inequality.

2.2. Indicators and methods

The chapter is to examine China’s “new normal” state by comparing related indicators with 14 other countries typically scattered in the world (except Africa). Considering the paper’s international angle, we make comparability and internationalism as the prime principles when selecting indicators utilized. Therefore, all indicators and data as follows are from UNDP, (http://hdr.undp.org) [ 8 ], the exception sources will be marked in addition at the right point.

2.2.1. Human development index (HDI)

The HDI represents a broader definition of well-being and provides a composite measure of three basic dimensions of human development: health (a long and healthy life), education (knowledge), and income (a decent standard of living) [ 9 ]. HDI is the most comparable and available indicator for measuring quality of life among countries.

2.2.2. Inequality indices (Gini, quintile, and Palma)

The World bank emphasizes, “To begin to understand what life is like in a country–to know, for example, how many of its inhabitants are poor–it is not enough to know that country’s per capita income. The number of poor people in a country and the average quality of life also depend on how equally–or unequally–income is distributed” [ 10 ]. The Gini Coefficient is the most frequently used inequality index as “the mean difference from all observed quantities” [ 11 ]. However, the Gini does not capture where in the distribution the inequality occurs. For this reason, other two indicators, quintile ratio, and Palma ratio, are also chosen in the paper, which are more clearly reflect the high income and low income gap, successfully excluding the influence of middle income people.

The quintile ratio (20:20 or 20/20 ratio) compares how much richer the top 20% of populations are to the bottom 20% of a given population, which is actually a part of the Gini Coefficient that prevents the middle 60% statistically obscuring inequality, meanwhile highlighting the difference between two poles.

The Palma Ratio, meaning the ratio of the top 10% of population’s share of gross national income (GNI), divided by the poorest 40% of the population’s share of GNI–could provide a more policy-relevant indicator of the extent of inequality in each country, and may be particularly relevant to poverty reduction policy. It is based on the work of Chilean economist Jose Gabriel Palma who found that the “middle classes” tend to capture around 50% of national income, while the other half is split between the richest 10% and poorest 40% [ 12 ].

2.2.3. Human capital index (HCI)

“A nation’s human capital endowment–the skills and capacities that reside in people and that are put to productive use–can be a more important determinant of its long-term economic success than virtually any other resource. This resource must be invested in and leveraged efficiently in order for it to generate returns–for the individuals involved as well as an economy as a whole” [ 13 ].

Graph 2 is drawn to show the relations among human development index and its three components, human, capital, and equality. Here, we emphasize that the HDI includes HCI, which account for two-thirds of HDI, even though education and health are not the whole HCI, but at least the major aspects; education and health are both capabilities residing in people, which is directly related to a person’s income and in social level to both quantity and quality of economic development; Equalization and justice are important complement of HDI, which also have promoting effects on people’s education and health by its benefiting mostly to the general public. That is, HDI, HCI, and equality are interrelated and tend to promote along the arrow directions, which constitute and cooperate the quality of development/quality of life.

Graph 2.

The promoting relations of equality, human capital, and human development.

All data used are registered in official sources. The international data for comparing among countries are from international organizations, UNDP. The method used in the chapter is mostly comparative analysis approaches with statistical graphs and tables.

3. Experimental

Here, we examine for comparing China’s quality of development with the representative countries by using the three serials indicators; and conduct comprehensive comparative analysis and evaluation.

3.1. Human development and living quality

3.1.1. hdi overall status.

Graph 3 shows the level of human development index of the 15 countries selected with various colors, which implies the overall quality of development and quality of life of different country groups. China is at the bottom of the row, ranked 90th in the world, and approximately accounts for 77% of the highest valued country, Norway; 79% of the United States, the typical capitalist country; and 82% of Japan, Asia’s most developed country. That means we have a long distance to go in quality of life.

Graph 3.

HDI in world context 2014.

Table 1 shows the overall level of HDI of four level groups, and the world and the developing countries. China, the second biggest economy in the world, is nearly 20% less than the level of the first 50 countries, and just at the average level of the world in quality of life.

| Groups | HDI | China % |

|---|---|---|

| Very high human development | 0.896 | 81.1 |

| High human development | 0.744 | 97.7 |

| Medium human development | 0.630 | 115.4 |

| Low human development | 0.505 | 144.0 |

| World | 0.711 | 102.3 |

| Developing countries | 0.660 | 110.2 |

Table 1.

Overall level of human development in different groups 2014.

3.1.2. HDI components

In Annex Table 1 , we make HDI and its component indicators in order respectively and make a sum rank in order to see the influence of each component. From Annex Table 1 and Graph 4 , we notice first that the general pattern does not change: (1) the upper ranked 8 countries are still upper but with changed ranks; (2) the lower seven countries are lower by the same rank with HDI order; (3) China retains at its bottom position by reordering, including total rank and almost all component cases (life expectancy of China is the only factor that does not row at the extreme bottom, which might somehow show off the medical condition or Chinese traditional medicine).

Graph 4.

Components of HDI by GNI order 2014.

Moreover, we find some prominent features in Annex Table 1 and Graph 4 : (1) Both Germany and UK’s re-ranks are upper by the same factor, “mean years of schooling” showing social sustainability, which imply the labor force and the civilized residents endowed by education; UK in Anglo-Saxon model with capitalist nature, has the similar pattern (8:1:8) with Germany (6:1:6) in “Rhine model,” but far from the pattern of USA (10:4:3); Czech Republic (with similar pattern 11:8:11) rows upper also by its “mean years of schooling,” which means education gains much attention in Czech as well. (2) Australia (3:3:7) has almost the opposite pattern with USA, but with better momentum of development in practical economy than USA. (3) The life expectancy order of Japan is at the first, which might reflect Japanese life style is very healthy.

3.2. Inequality

Equalization and justice are important complement of HDI, so we here analyze income inequality standing for measuring social equality and justice, although which is far from comprehensive but essential and quantitative. According to the data of the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s Gini coefficient has ever peaked to 49.1 in 2008, began to decline since 2010, to 46.9 in 2014, along with policy’s functioning.

Graph 5 shows that, in the Gini coefficient case, China (2014) performs better than the three Latin countries and the two typical capitalist countries, USA and UK. However, the quintile ratio that shows the polarization in income distribution by the top 20% to the bottom 20%, has different performance: China’ s value of quintile ratio is only better than that of the three Latin countries but worse than USA and UK, and far worse than other countries included; The Palma ratio, the richest 10% of population’s share of gross national income divided by the poorest 40%’s share, provides support to the quintile’s case.

From the computing results in Table 2 , we can see more clearly that China’s polarization in income distribution, i.e., the highest income group to the lowest, excluding the influence of middle income people is conspicuous worse than the Gini performance with the influence of middle income populations included, by observing the deviations from the average of the 15 countries considered.

Graph 5.

Income inequalities by Gini order 2014.

| HDI rank total | Country | Indicators of income inequality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile ratio | Palma ratio | Gini coefficient | ||

| 14 | Sweden | 3.75 | 0.90 | 26.08 |

| 28 | Czech | 3.88 | 0.93 | 26.39 |

| 1 | Norway | 4.00 | 0.93 | 26.83 |

| 4 | Denmark | 3.96 | 0.94 | 26.88 |

| 24 | Finland | 4.04 | 0.98 | 27.79 |

| 6 | Germany | 4.72 | 1.14 | 30.63 |

| 20 | Japan | 5.39 | 1.22 | 32.11 |

| 3 | Switzerland | 5.23 | 1.21 | 32.35 |

| 2 | Australia | 5.85 | 1.32 | 34.01 |

| 90 | China | 10.08 | 2.08 | 37.01 |

| 14 | UK | 7.64 | 1.67 | 38.04 |

| 8 | USA | 9.79 | 1.96 | 41.12 |

| 40 | Argentina | 10.62 | 2.25 | 43.57 |

| 74 | Mexico | 11.13 | 2.84 | 48.07 |

| 75 | Brazil | 16.87 | 3.77 | 52.67 |

| 15 countries | Average | 7.13 | 1.61 | 34.90 |

| % deviation to average | China | 41.41 | 29.29 | 6.04 |

| Argentina | 49.00 | 40.03 | 24.83 | |

| Mexico | 56.11 | 76.27 | 37.72 | |

| Brazil | 136.59 | 134.55 | 50.90 | |

Table 2.

Fifteen countries’ comparison of income inequality by Gini Order 2014.

Of course, the income inequality in three Latin countries show much worse cases than in China; and their polarization is even much worse than their Gini case as well. That is probably the reason why the Latin countries could not performance better with so much endowment of natural resources. Therefore, equality and social justice in China as institutional environment given by the government should improve continuously for the sake of promoting the living quality of the people.

In addition, China is a socialist country as its Constitution expressed, and in case any adverse effect happens, it is very necessary for China to have higher pursuit in equality and social justice, e.g., reach to 35/7/1.5 (Gini/quintile/Palma), equivalently the average level of listed 15 countries, close to the level of UK (38/7.6/1.7) or Australia (34/5.9/1.3), as the minimum pursuits in 5–10 year, from 37/10/2, the currently level of China by the inequality index.

3.3. Human capital

Generally observing the history and experiences of all developed countries, it is common nature that every country pays enough attention to two factors: labor force and ecological environment, which are two bases of a human society. We here focus on labor force only for which is the most active factor for social economic development, though ecological environment is a big problem in China.

A group of American economists, such as Gary S. Becker, T. W. Schultz, George J. Stigler, Milton Friedman, etc., advocate the concept “human capital” to describe the quality of labor force [ 14 ]. Now, that the concept of human capital has been widely spread and accepted, and for the sake of comparing the quality of labor force internationally, we take the advantage of data availability to use it, even though we are a bit shy to treat labors as capital.

3.3.1. Human capital index and its aging structure

From Graph 6 , we can see that China’s human capital level rows at the lowest position in the other 14 countries, and upper than Brazil. In aging structure, it seems a common problem currently for all other 14 countries but China. In fact, the aging issue in China is becoming a problem because of China’s one-child policy which lasted 35 years. So, it becomes urgent to promote the quality of labors, if given the labor force participation and employment rate.

Graph 6.

Human capital index and its structure by overall order 2015.

3.3.2. Labor force participation and employment

China has no doubt the best performance both in labor force participation and employment ( Graph 7 ). Then, we see the quality of labor, for “education and training are the most important investments in human capital” [ 14 ].

Graph 7.

Employment and labour force paticipationparticipation by unemployment order

3.3.3. Education efficiency

From 15-year-old students’ performance in 2012, we find that the quality of labor force in China is worth optimistic for the future. But on second thought, Chinese is so diligent and smart that China should have the highest quality of development, but China’s HDI is at the 90th position, just at the middle level of the world. Why? There might be many reasons involved, may we have another paper to discuss the issue for the limit of article length.

4. Results and conclusions

From what has been discussed above, we conclude the following results:

Equalization and justice are important complement of HDI; The HDI includes HCI; The two major parts of HCI, education and health, are both capabilities residing in people, which directly related to a person’s income and in social level to both quantity and quality of economic development, and directly benefited from equalization and justice; Hence, HDI, HCI, and equality are inter relatedly constitute and cooperate the quality of development/quality of life. ( Graph 2 ) The economy (income) is the business of market, while the education and health of labors and the income distribution should be supervised and guaranteed by the government; that is to say that the quality of life should be achieved by the combination of government and market.

The overall level of HDI in China is nearly 20% less than the level of the first 50 countries, and just at the average level of the world in quality of life. Among the selected 15 countries, China is at bottom of the row, ranked 90th in the world, and approximately accounts for 77% of the highest valued country, Norway; 79% of the United States, the typical capitalist country; and 82% of Japan, the Asian most developed country. That means we have a long way to go in quality of life ( Table 1 , Graph 3 ).

Both Germany and UK have best performance in “Mean years of schooling,” which implying the labor force and the civilized residents endowed by education; UK in Anglo-Saxon model with capitalist nature, has the similar pattern (8:1:8, means rank of health/education/economy) with Germany (6:1:6) in “Rhine model,” but far from the pattern of USA (10:4:3); Czech Republic (with similar pattern 11:8:11) rows upper also by its “Mean years of schooling,” which means education gains much attention in Czech as well. Australia (3:3:7) has almost the opposite pattern with USA, but with better momentum of development in practical economy than USA. China should not take the model of USA, but learn more from Germany, UK and Australia, and Czech, that is, pay more attention to education for a civilized society in the future (Annex Table 1 ).

In the Gini coefficient case, China (2014) performs better than the three Latin countries and the two typical capitalist countries, USA and UK; China’ s quintile ratio is only better than that of the three Latin countries but worse than USA and UK; The Palma ratio provides support to the quintile’s case. That is, China’s polarization in income distribution is conspicuous worse than the Gini performance with the influence of middle income populations included. Hence, we should concern more of the low income groups ( Graph 5 , Table 1 ).

The income inequality of three Latin countries shows much worse cases than in China, and their polarization is even much worse than their Gini case as well. Serious inequality cannot bring a developed economy from the lesson of Latin countries. Therefore, equality and social justice in China as institutional environment given by the government should improve continuously for the sake of promoting the living quality of the people ( Table 1 ).

China is a socialist country as its constitution expressed, and in case any adverse effect happens, it is very necessary for China to have higher pursuit in equality and social justice, e.g., reach to 35/7/1.5 (Gini/quintile/Palma), equivalently the average level of listed 15 countries, close to the level of UK (38/7.6/1.7) or Australia (34/5.9/1.3), as the minimum pursuits in 5–10 years, from 37/10/2, the currently level of China by the inequality index ( Table 1 ).

China’s human capital Index row at the lowest position among the countries, only better than Brazil’s ( Graph 6 ). But as the positive factor of HCI, China has the best performance in all 15 countries both in labor force participation and employment ( Graph 7 ). From 15-year-old students’ performance in education efficiency in 2012, the quality of labor force in China is worth optimistic for the future ( Graph 8 ). Therefore, China has its advantages in human capital, and furtherly in the potential of development.

It is possible to achieve better growth speed while we are focusing on the quality of development.

Graph 8.

Education quality by order of science 2012 (Pperformance of 15-year-old student).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Tomáš Wroblowský, VSB, Czech Republic, for his feedback and suggestions regarding data and the quantitative methodologies used in the chapter.

We would also like to thank anonymous referees for their valuable comments and corrections to our English writing.

We would like to express our gratitude to both Social Science Foundation (Serial No: HB15LJ002), funded by Hebei Programming Office for Philosophy and Social Science, China, and Soft Science Foundation (Serial No: 16457699D), funded by Hebei Bureau of Science and Technology, China, for providing us with research funds.

The research is supported by the SGS project of VŠB-TU Ostrava Czech Republic under No. SP2016/11.

JEL classification: E6, F5, F6, O15, O5

- 1. Becker, Gary S. (1993 third edition). Human Capital. The National Bureau of Economic Research. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago and London. ISBN 0-226-04120-4.

- 2. Cai, Fang. (2016). Let the world know China’s New Normal of economic development. http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2016-06/16/nw.D110000renmrb_20160616_2-07.html.

- 3. Ceriani, Lidia. Verme, Paolo. (2012). The origins of the Gini index: extracts from Variabilità e Mutabilità (1912) by Corrado Gini. J Econ Inequal. (2012) 10: 424–443.

- 4. Cobham, Alex. Sumner, Andy. (2013). Putting the Gini back in the bottle “The Palma” as a policy-relevant measure of inequality. Mimeograph. London: King’s Collage London. http://www.socialprotectionet.org/sites/default/files/cobham-sumner-15march2013.pdf.

- 5. Jahan, Selim, et al. (2015). Human development report 2015. Published for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). New York. eISBN 978-92-1-057615-4. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2015_human_development_report.pdf.

- 6. Jin, Bei. (2015). On the New Normal of China’s economic development. China Industrial Economics. No.1.

- 7. Leopold, Till, et al. (2015). The human capital report 2015. World Economic Forum. Geneva. ISBN 92-95044-49-5. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Human_Capital_Report_2015.pdf.

- 8. Li, Yang. (2015). The New Normal of China’s economy is different to the New Normal of globle economy. http://soci.cssn.cn/ddzg/ddzg_ldjs/ddzg_jj/201503/t20150312_1542335.shtml.

- 9. Lin, Yifu. (2016). Why China can increase as planned. http://beltandroad.zaobao.com/beltandroad/analysis/story20160407-602338.

- 10. Liu, Wei. (2015). The New Normal of China’s economy and its new strategy of economic development. China Academic Journal Electronic Publishing House.

- 11. Tatyana P. Soubbotina. (2004). Beyond economic growth an introduction to sustainable development. World Bank Publications. ISBN 9780821359334. http://www.worldbank.org/depweb/english/beyond/global/chapter5.html

- 12. Trends in the human development index, 1990–2014. http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/Trends. Human Development Report 2015: Work for Human Development. United Nations Development Programme. New York. 2015. eISBN 978-92-1-057615-4.

- 13. Wu, Jinglian. (2015). Accurately grasp the two characteristics of the New Normal. http://theory.people.com.cn/n/2015/0504/c49154-26942603.html.

- 14. Yao, Yang. (2016). Across the Middle-Income Trap: advantages and challenges in China. Vol.028, National School of Development, Peking University.

© 2017 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This conference paper is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Edited by Jaromir Gottvald

Published: 01 February 2017

By Vladimír Kulil

1560 downloads

By Li Qiong

1735 downloads

By Jindra Peterková and Zuzana Wozniaková

1528 downloads

IntechOpen Author/Editor? To get your discount, log in .

Discounts available on purchase of multiple copies. View rates

Local taxes (VAT) are calculated in later steps, if applicable.

- Get IGI Global News

- All Products

- Book Chapters

- Journal Articles

- Video Lessons

- Teaching Cases

- Recommend to Librarian

- Recommend to Colleague

- Fair Use Policy

- Access on Platform

Export Reference

- Advances in Human Resources Management and Organizational Development

- e-Book Collection

- Business Knowledge Solutions e-Book Collection

- Computer Science and IT Knowledge Solutions e-Book Collection

- Social Sciences Knowledge Solutions e-Book Collection

- Business and Management e-Book Collection

- Environmental, Agricultural, and Physical Sciences e-Book Collection

- Social Sciences and Humanities e-Book Collection

- e-Book Collection Select

Research on Cross-Industry Digital Transformation Under the New Normal: A Case Study of China

With the rapid development of cloud computing, big data, artificial intelligence, 5G and other digital technology, the digital wave characterized by digital networking, information and intelligence has swept the world (Cloud Computing and big data Research Institute of China Academy of Information and Communications, 2021). In addition, the COVID-19 epidemic has also accelerated the process of digital transformation. Opinion papers (Fletcher & Griffiths, 2020), reports of advisory and opinion-makers (UN opinion Governors 2020 McKinsey Digital, 2020), and statements of respected personalities from the worlds of science and business (Martin-Barbero, 2020) have confirmed that the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly led to organizational change, forced a redefinition of business strategy, and acted as a catalyst for digital transformation in many areas of the economy, health care, and education (Renata, 2020). By 2020, the global digital economy has accounted for more than 40% of GDP (Figure 1). The digital economy has become an important power source of world economic growth and the trend of digitization has been irresistible.

Complete Chapter List

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 23 July 2024

Suspected silent pituitary somatotroph neuroendocrine tumor associated with acromegaly-like bone disorders: a case report

- Tongxin Xiao 1 ,

- Xinxin Mao 2 ,

- Ou Wang 1 ,

- Yong Yao 3 ,

- Kan Deng 3 ,

- Huijuan Zhu 1 &

- Lian Duan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4213-474X 1

BMC Endocrine Disorders volume 24 , Article number: 121 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

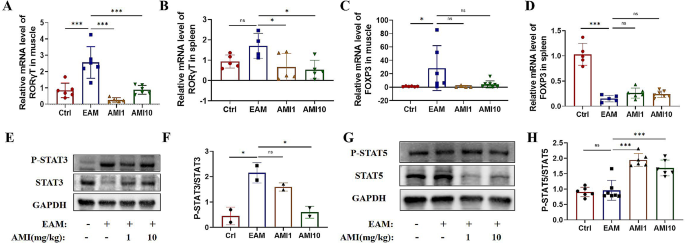

Growth hormone (GH) positive pituitary neuroendocrine tumors do not always cause acromegaly. Approximately one-third of GH-positive pituitary tumors are classified as non-functioning pituitary tumors in clinical practice. They typically have GH and serum insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels in the reference range and no acromegaly-like symptoms. However, normal hormone levels might not exclude the underlying hypersecretion of GH. This is a rare and paradoxical case of pituitary tumor causing acromegaly-associated symptoms despite normal GH and IGF-1 levels.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 35-year-old woman with suspicious acromegaly-associated presentations, including facial changes, headache, oligomenorrhea, and new-onset diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. Imaging found a 19 × 12 × 8 mm pituitary tumor, but her serum IGF-1 was within the reference, and nadir GH was 0.7ng/ml after glucose load at diagnosis. A thickened skull base, increased uptake in cranial bones in bone scan, and elevated bone turnover markers indicated abnormal bone metabolism. We considered the pituitary tumor, possibly a rare subtype in subtle or clinically silent GH pituitary tumor, likely contributed to her discomforts. After the transsphenoidal surgery, the IGF-1 and nadir GH decreased immediately. A GH and prolactin-positive pituitary neuroendocrine tumor was confirmed in the histopathologic study. No tumor remnant was observed three months after the operation, and her discomforts, glucose, and bone metabolism were partially relieved.

Conclusions

GH-positive pituitary neuroendocrine tumors with hormonal tests that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for acromegaly may also cause GH hypersecretion presentations. Patients with pituitary tumors and suspicious acromegaly symptoms may require more proactive treatment than non-functioning tumors of similar size and invasiveness.

Peer Review reports

Acromegaly is mainly associated with growth hormone (GH) hypersecretion caused by GH/somatotroph pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs) [ 1 ]. Symptoms like facial changes and other acromegaly-related metabolic abnormalities are clues for the suspicion of acromegaly, but they are not mandatory for diagnosis [ 2 , 3 ]. Biochemical tests, including serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and nadir GH during oral glucose tolerant test (OGTT), are critical to diagnosing acromegaly. Patients with normal IGF-1 levels are usually considered acromegaly unlikely [ 1 ]. The cut-off of nadir GH in the OGTT is traditionally 1.0ng/ml, while increasing clinicians consider 0.4ng/ml as a better diagnostic cut point when using assays capable of detecting lower GH levels [ 1 , 2 ]. However, these diagnostic criteria still have limitations. For example, mild acromegaly could exhibit nadir GH < 0.4ng/ml [ 4 ], and the levels of IGF-1 could also be affected by physiological and non-physiological factors [ 1 ].

Up to 30% of patients with PitNETs synthesizing GH show normal IGF-1 and nadir GH levels [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Accordingly, silent GH PitNET is commonly used to describe clinical and biochemical non-functioning GH immunostaining-positive PIT-1 (pituitary specific transcription factor 1) lineage PitNETs. [ 7 , 8 ] Silent GH PitNET is a rare entity (about 2–4% of resected PitNETs), and they might have a younger onset age and a higher risk of recurrence compared with common non-functioning PitNETs [ 7 , 9 , 10 ]. A continuous spectrum may describe the PitNETs with different clinical presentations, serum hormone levels, and pathologic characteristics: functioning (typical symptoms and elevated hormones), whispering or subtle (subtle symptoms with elevated hormones), clinically silent (no symptom with elevated hormones), and silent (no symptom with normal serum hormones) tumors [ 6 , 10 ]. In addition to typical acromegaly, the classification and surveillance strategy of cases with mild hormone elevation or associated symptoms is still ambiguous. Clinically silent cases with elevated GH and IGF-1 were occasionally reported [ 3 , 11 , 12 ], but no reports of cases with acromegaly-related symptoms and normal hormone levels have been published to our knowledge.

Here, we report a paradoxical case with suspicious acromegaly symptoms, associated complications, and pituitary macroadenoma. The serum IGF-1 was normal, and nadir GH was 0.7ng/ml. A GH-positive PIT-1 lineage pituitary neuroendocrine tumor was confirmed after surgery, with IGF-1 and nadir GH decreasing significantly. We consider this case an untraditional subtype within the spectrum of GH PitNETs, as it does not align with the classic definitions of either acromegaly or silent GH-PitNETs. We aim to highlight that acromegaly-associated presentations might occur in clinically subtle or silent somatotroph PitNETs that cannot be diagnosed as acromegaly.

A 35-year-old woman complained of oligomenorrhea and acromegaly-like facial changes of 13 years duration. She delivered a healthy baby following natural conception during this period, and her last menstruation was one year previously, after induced abortion for two consecutive pregnancy losses at eight weeks. She occasionally had headaches, excessive perspiration, and lower back discomfort, while she denied galactorrhea, taking contraceptives or any medications that may contain estrogen, and a familial history of pituitary disease. Her height and weight were 163 cm and 78 kg (with an increase of 23 kg since the onset of symptoms). She underwent surgery for a left occipital bone fracture because of a car accident at the age of 19, after which she gradually developed strabismus. The patient had late-stage pregnancy-induced hypertension, which resolved after delivery. She was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus one year ago but refused treatment. On physical examination, she showed widened nasal alae, thickened lip, and an enlarged tongue without enlargement of the hands and feet, suspected as acromegaly. Dynamic pituitary MRI found a 19 × 12 × 8 mm lesion in the pituitary gland without stalk deviation or extension into the cavernous sinus (Fig. 1 ). IGF-1 was measured twice with a 15-day interval, showing 212 and 133ng/ml (reference: 63–223ng/ml). The nadir GH after 75 g glucose load was 0.7ng/ml (Table 1 ). Other pituitary hormones stayed normal. Meanwhile, a thickened skull base was observed in CT (Fig. 2 ), and the whole-body bone scan indicated diffusely increased uptake in cranial bones. Bone turnover markers were elevated, with β-CTX and TP1NP measuring 2.06ng/ml and 135ng/ml, respectively. T-25OHD was 15.8ng/ml, and ALP was 213U/L. Her serum calcium, phosphate, and bone mineral density (Z-score at lumbar spine L1-L4: -0.7) were within the normal range (Table 1 ). These raised suspicion for metabolic bone disease. In addition, she had confirmed diabetes mellitus with Hb1Ac of 10.8% and hypertriglyceridemia with triglyceride rising to 3.96mmol/L. Hepatic steatosis was confirmed, with a mild impaired liver function (ALT ranged from 28 to 61U/L). A thorough body inspection did not find other suspected tumors. No pathogenic variants were identified by whole exome sequencing (WES), while two variants of uncertain significance were detected in the FOXA2 and LEPR genes (Supplementary Table 1 ).

MRI image of the pituitary tumor. A , T1-weighted image (T1-WI) contrast-enhanced sagittal plane reveals a hypointense nodule, B , T1-WI contrast-enhanced coronal plane shows a macroadenoma across the right and left of the pituitary, without extension into the cavernous sinus or optical chiasm. Arrows indicated the location of the lesion

Head CT image showing a thickened skull base. A , Head CT image showed a thickened skull base; B, Head CT image showed a thickened skull base and the skull lesion caused by a previous traffic accident

In light of these suspicious symptoms, complications, and borderline nadir GH, we consider the possibility of a silent GH-secreting pituitary neuroendocrine tumor in this patient. Then, she received endoscopic transsphenoidal tumor resection surgery, with the soft pituitary tumor removed. In the histopathological examination of the resected specimen (Fig. 3 ), a PIT-1 lineage PitNET without other positive-staining transcription factors was confirmed. It was partially positive for GH while more weakly staining in PRL. Its Ki-67 proliferation index was 1%. CAM5.2 staining indicated a sparsely granulated pattern, and SSTR2 was positive. The staining of other pituitary hormones was negative. After the surgery, the IGF-1 dropped to 77ng/mL in 3 days and remained at 125ng/mL three months post-operation. Similarly, β-CTX and P1NP decreased significantly to 1.20ng/mL and 86.0ng/mL 3 months after surgery. (Table 1 ) She now takes one tablet of metformin sitagliptin twice daily and vitamin D3 1000U daily regularly. No new-onset discomfort was reported. 3 months after surgery, her fast blood glucose, Hb1Ac, and triglyceride were 7.9 mmol/L, 7.0%, and 3.41 mmol/L, respectively. No remnant of pituitary tumor was observed at the last visit.

Pathologic and immunohistochemical image of the pituitary neuroendocrine tumor. A , H&E staining shows typical pituitary neuroendocrine tumor cells (×200). B , GH was moderately positive. C , PIT-1 was strongly positive. D , PRL was scattered and focal positive. E , ki-67 proliferative activity was approximately 1%. F , CAM5.2 was in a sparsely granulated pattern

Discussion and conclusions

We report a paradoxical PitNET case showing several likely acromegaly-associated presentations but no elevation of IGF-1 or nadir GH after glucose load was confirmed. This patient experienced partial relief of discomforts after the pituitary surgery, and immunostaining showed a PIT-1 lineage tumor with moderately positive GH and a much weaker staining of PRL. We consider this case possibly an untraditional clinically silent GH pituitary PitNET.

In our case, both two random IGF-1 tests taken two weeks apart were in the normal range, with a borderline nadir GH. We observed a two-fold decrease in IGF-1 levels in tests taken two weeks apart, but this difference might simply be due to normal sampling and testing variations. Despite the limitations in biochemical diagnostic criteria for acromegaly and a possible weak impact of the metabolism of IGF-1 because of hepatic steatosis, it is the fact that these results could not distinguish the case from patients without GH PitNETs. However, this PitNET might still have a capacity for GH hypersecretion, even if it is relatively moderate. According to the theory of the continuous spectrum of PitNETs ranging from silent to functioning [ 10 ], the rising hormones may not cause obvious clinical symptoms [ 12 , 13 ]. Meanwhile, it is widely accepted that clinical symptoms develop after the elevation of corresponding hormones. Still, our case showed a rare scenario in which a young woman had several acromegaly-like presentations with a normal IGF-1 and 0.7ng/ml nadir GH. Although her amenorrhea was likely due to uterine lesions, other symptoms like facial changes and comorbidities (including diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and metabolic bone disease) were all possibly acromegaly-associated [ 1 ]. For example, acromegaly is associated with abnormal skeletal metabolism, leading to elevation of bone turnover markers, lower bone quality, and increased risks of fractures [ 14 , 15 ]. In our case, decreasing bone turnover markers after pituitary tumor resection supported that the GH-positive PitNETs had at least a partial influence on her abnormal bone metabolism. Likewise, metabolic complications in this case, including diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis, are also diseases recommended for screening in acromegaly [ 1 ]. The concurrence of these diseases is less likely to be a coincidence without an underlying hypersecretion of GH.

Meanwhile, differential diagnoses of a thickened skull base, increased radioactive uptake in a bone scan, and elevated bone turnover markers should also be considered. These differential diagnoses mainly included other metabolic bone diseases, like Paget disease of bone, osteopetrosis, fibrous dysplasia of bone, and pachydermoperiostosis [ 16 ]. However, this patient did not meet the clinical diagnosis criteria for most of these diseases. She had no enlargement of hands or hypertrophic skin changes, while WES did not identify any relevant gene mutation. Considering the rapid decline of IGF-1 and nadir GH after the surgery, together with her early-onset diabetes mellitus and hypertriglyceridemia without relevant familial history, from a monistic perspective, we suppose that it is highly likely that her GH-positive PitNET, which may cause a relatively moderate but long-lasting GH secretion, contributed most to the abnormal condition. Still, given the atypical and rare combination of active clinical symptoms and silent test results in this case, we conservatively considered that other comorbidities would not be completely ruled out at this stage. A long-term follow-up to observe whether her presentations and bone turnover markers could be relieved well without recurrence of the PitNET could assist in the final confirmation of the role of GH-PitNETs in this case.

As for pathologic classification, because of the predominant GH staining, a weaker PRL staining, and no TSH staining, this PIT-1 lineage PitNET was classified as a mammosomatotroph tumor. GH and PIT-1 positive PitNETs span a wide range of heterogeneous tumors with different clinical characteristics, like aggressiveness and secretion activity [ 8 , 17 ]. Silent or subtle GH PitNETs share the pathologic classification with typical acromegaly, but their distribution of specific pathological subtypes differs. More tumors are likely expressing multiple pituitary hormones or even multiple transcription factors in silent PitNETs [ 7 , 10 ]. For example, over half of silent GH PitNETs could have co-positive staining of PRL, as shown in our case, which is much more than those causing acromegaly [ 9 ]. Although the tumor, in this case, did not find invasion on imaging and its Ki-67 proliferation index was 1%, a close follow-up is recommended because it also exhibited several high-risk features.

For PitNETs that can express hormones like GH or ACTH without inducing noticeable hormone level elevations and symptoms, the underlying mechanisms remained unclear. An intriguing hypothesis is that some of these PitNETs might display a more primitive stage of differentiation [ 5 ]. Therefore, they may tend to retain the ability to express more pituitary hormones or even transcription factors, while hormone synthesis or secretion functions are less developed. This may also explain why PitNETs with higher aggressiveness are more common in silent GH or ACTH tumors [ 10 , 18 ]. Another common assumption is that a short disease duration causes a lack of clinical change, especially when the secretion capacity of somatotroph PitNETs is moderate. However, a short disease duration could not explain our case since her clinical presentations seemed more apparent than the rechecked hormone levels at diagnosis.

Additionally, we propose another potential explanation for biochemically silent cases with GH hypersecretion symptoms: GH-positive PitNETs may also secret GH cyclically, similar to cyclic Cushing disease. There are reports of ‘silent’ corticotroph PitNETs showing associated manifestations without remarkable biochemical tests [ 19 ], but no similar case has yet been reported in somatotroph PitNETs. It is possible that our patient was tested at her trough in GH concentration, but the long-lasting effect of cyclic hypersecretion of GH and IGF-1 may cause associated symptoms. The mechanisms of cyclic Cushing disease are also undetermined. Hypotheses include hypothalamic dysfunction, the infarction or bleeding of pituitary tumors, and uncommon sensitivity to positive and negative feedback in specific patients [ 20 , 21 ]. These assumptions may also be applied to GH-positive tumors. Since the half-life of IGF-1 is longer than serum cortisol in Cushing’s disease, a distinct fluctuation caused by ‘cyclic acromegaly’ would be more challenging to detect if such tumors indeed exist.

In summary, a normal IGF-1 and nadir GH at diagnosis cannot exclude the possibility of underlying GH hypersecretion from pituitary tumors in patients with suspicious acromegaly presentations. Tumors resection might improve acromegaly-like symptoms, and silent GH PitNETs have a higher risk of invasiveness and recurrence. Therefore, a more proactive surgical treatment should be considered in suspicious GH PitNETs than non-functioning tumors of similar size.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

Growth hormone

Insulin-like growth factor 1

Pituitary neuroendocrine tumors

Oral glucose tolerant test

Pituitary specific transcription factor 1

Carboxy-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type 1 collagen

Total procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide

Fleseriu M, Langlois F, Lim DST, Varlamov EV, Melmed S. Acromegaly: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(11):804–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(22)00244-3 .

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Ershadinia N, Tritos NA. Diagnosis and treatment of Acromegaly: an update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(2):333–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.007 .

Sakharova AA, Dimaraki EV, Chandler WF, Barkan AL. Clinically silent somatotropinomas may be biochemically active. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):2117–21.

Ribeiro-Oliveira A, Faje AT, Barkan AL. Limited utility of oral glucose tolerance test in biochemically active acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(1):17–22. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-10-0744 .

Chinezu L, Vasiljevic A, Trouillas J, Lapoirie M, Jouanneau E, Raverot G. Silent somatotroph tumour revisited from a study of 80 patients with and without acromegaly and a review of the literature. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176(2):195–201.

Wade AN, Baccon J, Grady MS, Judy KD, O’Rourke DM, Snyder PJ. Clinically silent somatotroph adenomas are common. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165(1):39–44. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-11-0216 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Langlois F, Woltjer R, Cetas JS, Fleseriu M. Silent somatotroph pituitary adenomas: an update. Pituitary. 2018;21(2):194–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-017-0858-y .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Asa SL, Mete O, Perry A, Osamura RY. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of Pituitary tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2022;33(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-022-09703-7 .

Langlois F, Lim DST, Varlamov E, Yedinak CG, Cetas JS, McCartney S, et al. Clinical profile of silent growth hormone pituitary adenomas; higher recurrence rate compared to silent gonadotroph pituitary tumors, a large single center experience. Endocrine. 2017;58(3):528–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-017-1447-6 .

Drummond J, Roncaroli F, Grossman AB, Korbonits M. Clinical and pathological aspects of Silent Pituitary Adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(7):2473–89. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-00688 .

Sidhaye A, Burger P, Rigamonti D, Salvatori R. Giant somatotrophinoma without acromegalic features: more quiet than silent: case report. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(5):E1154. discussion E.

PubMed Google Scholar

Giordano M, Samii A, Fahlbusch R. Aggressive somatotrophinomas lacking clinical symptoms: neurosurgical management. Neurosurg Rev. 2018;41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-017-0940-y .

Pestell R, Herington A, Best J, Boolell M, McKelvie P, Arnott R, et al. Growth hormone excess and galactorrhoea without acromegalic features. Case reports. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98(1):92–7.

Giustina A. Acromegaly and bone: an update. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2023;38(6):655–66. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2023.601 .

Mazziotti G, Lania AGA, Canalis E, MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE. Bone disorders associated with acromegaly: mechanisms and treatment. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;181(2):R45. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-19-0184 .

Kartal Baykan E, Türkyılmaz A. Differential diagnosis of Acromegaly: pachydermoperiostosis two new cases from Turkey. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2022;14(3):350–5. https://doi.org/10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2021.2020.0301 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wan X-Y, Chen J, Wang J-W, Liu Y-C, Shu K, Lei T. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of Pituitary Adenomas/Pituitary neuroendocrine tumors: clinical practices, controversies, and perspectives. Curr Med Sci. 2022;42(6):1111–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11596-022-2673-6 .

Portovedo S, Neto LV, Soares P, Carvalho DPd, Takiya CM, Miranda-Alves L. Aggressive nonfunctioning pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2022;39(4):183–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10014-022-00441-6 .

Alsavaf MB, Wu KC, Finger G, Salem EH, Castello Ruiz MJ, Godil SS, et al. A silent corticotroph adenoma: making the case for a pars intermedia origin. Illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2023;5(20). https://doi.org/10.3171/CASE2350 .

Cai Y, Ren L, Tan S, Liu X, Li C, Gang X, et al. Mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment of cyclic Cushing’s syndrome: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;153:113301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113301 .

Nowak E, Vogel F, Albani A, Braun L, Rubinstein G, Zopp S, et al. Diagnostic challenges in cyclic Cushing’s syndrome: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11(8):593–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00150-X .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This research was funded by the National High-Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-A-155, 2022-PUMCH-B-016).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Key Laboratory of Endocrinology of National Health Commission, Department of Endocrinology, State Key Laboratory of Complex Severe and Rare Diseases Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

Tongxin Xiao, Ou Wang, Huijuan Zhu & Lian Duan

Department of Pathology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

Department of Neurosurgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

Yong Yao & Kan Deng

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

T.X.: writing the original draft and collecting data. X.M.: pathologic data and discussion. O.W.: participate in bone abnormality discussions. Y.Y. and K.D.: reviewing and editing. H.Z.: supervision and reviewing. L.D.: collecting data, supervision, and reviewing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lian Duan .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

Consent for publication

The patient reported in the manuscript provided her written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Xiao, T., Mao, X., Wang, O. et al. Suspected silent pituitary somatotroph neuroendocrine tumor associated with acromegaly-like bone disorders: a case report. BMC Endocr Disord 24 , 121 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-024-01657-7

Download citation

Received : 01 April 2024

Accepted : 16 July 2024

Published : 23 July 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-024-01657-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Pituitary neuroendocrinal tumor

- Silent somatotroph

- Skull lesion

BMC Endocrine Disorders

ISSN: 1472-6823

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Advertisement

Chaos and Confusion: Tech Outage Causes Disruptions Worldwide

Airlines, hospitals and people’s computers were affected after CrowdStrike, a cybersecurity company, sent out a flawed software update.

- Share full article

By Adam Satariano Paul Mozur Kate Conger and Sheera Frenkel

- July 19, 2024

Airlines grounded flights. Operators of 911 lines could not respond to emergencies. Hospitals canceled surgeries. Retailers closed for the day. And the actions all traced back to a batch of bad computer code.

A flawed software update sent out by a little-known cybersecurity company caused chaos and disruption around the world on Friday. The company, CrowdStrike , based in Austin, Texas, makes software used by multinational corporations, government agencies and scores of other organizations to protect against hackers and online intruders.

But when CrowdStrike sent its update on Thursday to its customers that run Microsoft Windows software, computers began to crash.

The fallout, which was immediate and inescapable, highlighted the brittleness of global technology infrastructure. The world has become reliant on Microsoft and a handful of cybersecurity firms like CrowdStrike. So when a single flawed piece of software is released over the internet, it can almost instantly damage countless companies and organizations that depend on the technology as part of everyday business.

“This is a very, very uncomfortable illustration of the fragility of the world’s core internet infrastructure,” said Ciaran Martin, the former chief executive of Britain’s National Cyber Security Center and a professor at the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford University.

A cyberattack did not cause the widespread outage, but the effects on Friday showed how devastating the damage can be when a main artery of the global technology system is disrupted. It raised broader questions about CrowdStrike’s testing processes and what repercussions such software firms should face when flaws in their code cause major disruptions.

How a Software Update Crashed Computers Around the World

Here’s a visual explanation for how a faulty software update crippled machines.

How the airline cancellations rippled around the world (and across time zones)

Share of canceled flights at 25 airports on Friday

50% of flights

Ai r po r t

Bengalu r u K empeg o wda

Dhaka Shahjalal

Minneapolis-Saint P aul

Stuttga r t

Melbou r ne

Be r lin B r anden b urg

London City

Amsterdam Schiphol

Chicago O'Hare

Raleigh−Durham

B r adl e y

Cha r lotte

Reagan National

Philadelphia

1:20 a.m. ET

CrowdStrike’s stock price so far this year

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Fern Fort University

China: the new normal case study analysis & solution, harvard business case studies solutions - assignment help.

China: The New Normal is a Harvard Business (HBR) Case Study on Leadership & Managing People , Fern Fort University provides HBR case study assignment help for just $11. Our case solution is based on Case Study Method expertise & our global insights.

Leadership & Managing People Case Study | Authors :: Richard H.K. Vietor, Haviland Sheldahl-Thomason

Case study description.

You can order --casename-- analysis and solution here

Order a Leadership & Managing People case study solution now

To Search More HBR Case Studies Solution Go to Fern Fort University Search Page

[10 Steps] Case Study Analysis & Solution

Step 1 - reading up harvard business review fundamentals on the leadership & managing people.

Even before you start reading a business case study just make sure that you have brushed up the Harvard Business Review (HBR) fundamentals on the Leadership & Managing People. Brushing up HBR fundamentals will provide a strong base for investigative reading. Often readers scan through the business case study without having a clear map in mind. This leads to unstructured learning process resulting in missed details and at worse wrong conclusions. Reading up the HBR fundamentals helps in sketching out business case study analysis and solution roadmap even before you start reading the case study. It also provides starting ideas as fundamentals often provide insight into some of the aspects that may not be covered in the business case study itself.

Step 2 - Reading the China: The New Normal HBR Case Study

To write an emphatic case study analysis and provide pragmatic and actionable solutions, you must have a strong grasps of the facts and the central problem of the HBR case study. Begin slowly - underline the details and sketch out the business case study description map. In some cases you will able to find the central problem in the beginning itself while in others it may be in the end in form of questions. Business case study paragraph by paragraph mapping will help you in organizing the information correctly and provide a clear guide to go back to the case study if you need further information. My case study strategy involves -

- Marking out the protagonist and key players in the case study from the very start.

- Drawing a motivation chart of the key players and their priorities from the case study description.

- Refine the central problem the protagonist is facing in the case and how it relates to the HBR fundamentals on the topic.

- Evaluate each detail in the case study in light of the HBR case study analysis core ideas.

Step 3 - China: The New Normal Case Study Analysis

Once you are comfortable with the details and objective of the business case study proceed forward to put some details into the analysis template. You can do business case study analysis by following Fern Fort University step by step instructions -

- Company history is provided in the first half of the case. You can use this history to draw a growth path and illustrate vision, mission and strategic objectives of the organization. Often history is provided in the case not only to provide a background to the problem but also provide the scope of the solution that you can write for the case study.

- HBR case studies provide anecdotal instances from managers and employees in the organization to give a feel of real situation on the ground. Use these instances and opinions to mark out the organization's culture, its people priorities & inhibitions.

- Make a time line of the events and issues in the case study. Time line can provide the clue for the next step in organization's journey. Time line also provides an insight into the progressive challenges the company is facing in the case study.

Step 4 - SWOT Analysis of China: The New Normal

Once you finished the case analysis, time line of the events and other critical details. Focus on the following -

- Zero down on the central problem and two to five related problems in the case study.

- Do the SWOT analysis of the China: The New Normal . SWOT analysis is a strategic tool to map out the strengths, weakness, opportunities and threats that a firm is facing.

- SWOT analysis and SWOT Matrix will help you to clearly mark out - Strengths Weakness Opportunities & Threats that the organization or manager is facing in the China: The New Normal

- SWOT analysis will also provide a priority list of problem to be solved.

- You can also do a weighted SWOT analysis of China: The New Normal HBR case study.

Step 5 - Porter 5 Forces / Strategic Analysis of Industry Analysis China: The New Normal