30,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Capital Punishment Essay for Students in English: 250 and 350 Words Samples

- Updated on

- Mar 12, 2024

Capital Punishment Essay: Capital punishment refers to sentencing a criminal with the death penalty after due process of law. This form of punishment can be traced back to the ancient Greek of the 7th century BC, which operated under the ‘Laws of Draco’. In addition to the Greeks, Romans also sanctioned citizens to the death penalty for murder, rape, arson, and treason.

Likewise, present-day India awards the death penalty for heinous crimes against mankind such as murder, criminal conspiracy, dacoity with murder, encouraging mutiny, and waging war against the central government. However, as we have evolved as humans, courts resort to this extreme form of punishment in rarest of the rare cases.

Also Read: Essay on Human Rights: Samples in 500 and 1500

Capital Punishment Essay in 250 Words

Capital punishment or the death penalty is the state-sanctioned execution of a person as punishment for a crime. It is usually the most severe punishment a judicial system can impose on offenders. It is usually reserved for the most serious crimes like rape and murder.

Since time immemorial, mankind has opted for different methods of capital punishment. From hanging, beheading, and firing squads to burning, stoning, and poisoning humans have used every possible way to execute offenders. Methods can vary but all these have one thing in common i.e. inhumanity.

Capital punishment, in all its forms, is considered barbaric. It is seen as cruel, savage, and a form of revenge, reminiscent of a bygone era where understanding and respect for human life were absent. Some argue that these methods even involve physical torture.

While some believe the death penalty deters crime, studies have shown no significant correlation between its use and a decrease in violent crimes. In simpler terms, the threat of execution does not necessarily prevent people from committing serious offences. Therefore, it becomes crucial to consider whether capital punishment truly serves any purpose in our modern world.

Owing to the controversial characteristics of this punishment option, the ‘Abolition of the Death Penalty’ has become one of the most prominent discussions in the United Nations. Besides, Human Rights activists and organisations also raise their voices against capital punishment. With all the ongoing debate, there is optimism that this inhuman practice might be done away with in the future.

Also Read: World Day for International Justice

Essay on Capital Punishment in 350 Words

Capital punishment or the death penalty has been a topic of contention in India. While the Supreme Court of India has reserved the death penalty for the rarest of rare cases, the penal process evokes a debate for and against this form of punishment.

One of the primary arguments in favour of capital punishment is deterrence i.e. fear of severe forms of the death penalty will reduce crimes. Supporters of this penal process are of the view that the threat of capital punishment prevents a potential offender from committing heinous crimes like murder, rape, war against the government, and abetment to mutiny. Also, they propound that the assertion of severe punishments upholds the safety and security of people as the state has the responsibility to maintain social order and safeguard its people.

However, people against capital punishment argue that the death penalty is inept in rehabilitating prisoners, which is the basic aim of any legal penal option. They also propose that punishment by execution does not deter people from committing crimes as individualist punishment overlooks broader social failures. Also, execution by barbaric measures shifts the responsibility of the state and peer groups from addressing the root causes of crime to individual punishment.

Another reason for concern regarding capital punishment is the risk of executing innocent individuals due to flaws in the justice system. The possibility of wrongful convictions highlights the serious consequences of irreparable harm of taking a person’s life. This irreversible consequence outlines the significance of strict legal procedures and safety measures to prevent miscarriage of justice.

Thus, the debate over capital punishment in India is a complex one, encompassing moral, legal, and societal considerations. While proponents argue for its necessity in ensuring justice and deterring crime, opponents raise valid concerns regarding its effectiveness, morality, and potential for miscarriages of justice. As the legal landscape continues to evolve, it is essential to critically examine these arguments and consider the broader implications of capital punishment on society and the individuals it affects.

It is time to #StopExecutions and #AbolishTheDeathPenalty – Join us now at https://t.co/LeukqEMJWA @RepEspaillat @EspaillatNY #LisaMontgomery #CoreyJohnson #DustinHiggs pic.twitter.com/wzTuklnrRx — Death Penalty Action (@DeathPenaltyAct) January 12, 2021

Ans: Yes. The legal system in India can grant capital punishment in case of murder, criminal conspiracy, abetment to mutiny, dacoity with murder, and waging war against the Union Government.

Ans: Start the essay on capital punishment by defining this penal process. Thereafter, cite arguments in favour and against the death penalty. Also, you can mention how the government and society benefit and lose through this ultimate yet barbaric form of justice.

Ans: Capital punishment refers to sentencing a criminal with the death penalty after due process of law.

Explore other essay topics for students here:

For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu.

Ankita Singh

Ankita is a history enthusiast with a few years of experience in academic writing. Her love for literature and history helps her curate engaging and informative content for education blog. When not writing, she finds peace in analysing historical and political anectodes.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

30,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today.

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Capital Punishment Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on capital punishment.

Every one of us is familiar with the term punishment. But Capital Punishment is something very few people understand. Capital punishment is a legal death penalty ordered by the court against the violation of criminal laws. In addition, the method of punishment varies from country to country. Where some countries hung the culprits until death and some shoot or give them a lethal injection.

Types of Capital Punishments

In this topic, we are going to discuss the various methods of punishment that are used in different countries. But, before that let’s talk about the capital punishments that people used in the past. Earlier, the capital punishments are more like torture rather than a death penalty. They used to strain and punish the body of the culprit to the extreme that he/she dies because of the pain and fear of torture.

Besides, modern methods are quicker and less painful than traditional methods.

- Electrocution – In this method, the criminal is tied to a chair and a high voltage current that can kill a man easily is passed through the body. In addition, it causes organ failure (especially heart).

- Tranquilization – This method gives the person a slow but painless death as the toxin injections are injected into his body that takes up to several hours for the criminal to die.

- Beheading – Generally, the Arab and Gulf countries use this method. Where they decide the death sentence by the crime of the person. Furthermore, in this method, they simply cut the person’s head apart from the body.

- Stoning – In this the criminal is beaten till death. Also, it is the most painful method of execution.

- Shooting – The criminal is either shoot in the head or in his/her chest in this method.

- Hanging – This method simply involves the hanging of culprit till death.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Advantages and Disadvantages of Capital Punishments

Although many people think that it’s a violation of human rights and the Human Rights Commission strongly opposes capital punishment still many countries continue this practice.

The advantages of capital punishment are that they give people an idea of what the law is capable of doing and the criminal can never escape from the punishment no matter who he/she is.

In addition, anyone who is thinking about committing a crime will think twice before committing a crime. Furthermore, a criminal that is in prison for his crime cannot harm anyone of the outside world.

The disadvantages are that we do not give the person a second chance to change. Besides, many times the real criminal escape the trial and the innocent soul of the prosecution claimed to guilty by false claims. Also, many punishments are painful and make a mess of the body of the criminal.

To conclude, we can say that capital punishment is the harsh reality of our world. Also, on one hand, it decreases the crime rate and on the other violates many human rights.

Besides, all these types of punishment are not justifiable and the court and administrative bodies should try to find an alternative for it.

FAQs about Capital Punishment

Q.1 What is the difference between the death penalty and capital punishment?

A.1 For many people the term death penalty and capital punishment is the same thing but there is a minute difference between them. The implementation of the death penalty is not death but capital punishment itself means execution.

Q.2 Does capital punishment decrease the rate of crime?

A.2 There is no solid proof related to this but scientists think that reduces the chances of major crimes to a certain level.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Capital Punishment and the Death Penalty Essay

Criminal law and procedure, historical development of criminal law, difference between legal and social parameters in criminal law, elements of a crime.

In most nations, there are two or three sorts of courts that have authority over criminal cases. A single expert judge typically handles petty offenses, but two or more lay justices in England may sit in a Magistrates’ Court. In many nations, more severe cases are heard by panels of two or more judges (Lee, 2022). Such panels are frequently made up of attorneys and lay magistrates, as in Germany, where two laypeople sit alongside one to three jurists. The French cour d’assises comprises three professional judges and nine lay assessors who hear severe criminal cases. Such mixed courts of professionals and ordinary residents convene and make decisions by majority voting, with lawyers and laypeople having one vote.

The United States Constitution permits every defendant in a non-petty matter the right to be prosecuted before a jury; the defendant may forgo this privilege and have the decision decided by a professional court judge. To guarantee the court’s fairness, the defense and prosecution can dismiss or challenge members whom they prove to be prejudiced (Lee, 2022). Furthermore, the defense and, in the United States, the prosecution has the right of vexatious challenge, which allows it to confront several participants without providing a reason.

One of the most primitive texts illustrating European illegitimate law appeared after 1066, when William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, conquered England. By the eighteenth century, European law addressed criminal behavior specifically, and the idea of trying lawbreakers in a courtroom context began to transpire (Zalewski, 2019). The English administration recognized a scheme referred to as common law, which is the method through which regulations that regulate a group of people are established and updated. Corporate law relates to public and illegal cases and is grounded on the establishment, adjustment, and expansion of laws by adjudicators as they make permissible judgments. These decisions become standards, prompting the consequences of impending cases.

Misdemeanors, offences, and sedition are the three types of unlawful offenses presented before the courts. Misdemeanors are petty infringements decided by penalties or confiscation of property; some are penalized by less than a year in prison. Offences are meaningfully more heinous felonies with heavier consequences, such as incarceration in a federal or state prison for a year or more. Treason is characterized as anything that breaches the country’s allegiance. Felonious law changes and is often susceptible to modification based on the ethics and standards of the period.

Parameters are values with changing attributes, principles, or dimensions that may be defined and monitored. A parameter is usually picked from a data set because it is critical to understanding the situation. A parameter aids in comprehending a situation, whereas a parameter defines the situation’s bounds (Doorn et al., 2018). The critical concept of the Legal parameter is that behaviors are restricted by unspoken criteria of deviance that are agreeable to both the controlled and those that govern them. Impartiality, fairness, and morality are all ideals conveyed by social justice, and they all have their origins in the overarching concept of law (Doorn et al., 2018). From a social standpoint, it involves various topics such as abortion, cremation, bio-genetics, human decency, racial justice, worker’s rights, economic freedom, and environmental concerns.

All crimes in the United States may be subdivided into distinct aspects under criminal law. These components of an offense must then be established beyond possible suspicion in a court of law to convict the offender (Ormerod & Laird, 2021). Many delinquencies need the manifestation of three crucial rudiments: a criminal act, criminal intent, and the concurrence of the initial two. Depending on the offense, a fourth factor called causality may be present.

First is the criminal act (Actus Reus): actus reus, which translates as “guilty act,” refers to any criminal act of an act that occurs. To be considered an unlawful act, an act must be intentional and controlled by the defendant (Ormerod & Laird, 2021). If an accused act on nature, they may not be held responsible for their conduct. Words can be deemed illegal activities and result in accusations such as perjury, verbal harassment, conspiracy, or incitement. On the contrary, concepts are not considered illegal acts but might add to the second component: intent.

Second is crime intent (Mens Rea): for a felonious offense to be categorized as a misconduct, the culprit’s mental circumstance must be reflected. According to the code of mens rea, a suspect can only be considered remorseful if there is felonious intent (Ormerod & Laird, 2021). Third is concurrence, which refers to the coexistence of intent to commit a crime and illicit behavior. If there is proof that the mens rea preceded or happened simultaneously with the actus reus, the burden of proving it is met. Fourth is causation: this fourth ingredient of an offense is present in most criminal cases, but not all. The link concerning the defendant’s act and the final consequence is called causation. The trial must establish outside a possible suspicion that the perpetrator’s acts triggered the resultant criminality, which is usually detriment or damage.

The risk of executing an innocent man cannot be entirely removed despite precautions and protection to prevent capital punishment. If the death penalty was replaced with a statement of life imprisonment, the money saved as a result of abolishing capital punishment may be spent in community development programs. The harshness of the penalty is not as efficient as the guarantee that the penalty will be given in discouraging crime. In other terms, if the penalty dissuades crime, there is no incentive to prefer the stiffer sentence.

Doorn, N., Gardoni, P., & Murphy, C. (2018). A multidisciplinary definition and evaluation of resilience: The role of social justice in defining resilience . Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure , 4 (3), pp. 112–123. Web.

Lee, S.-O. (2022). Analysis of the major criminal procedure cases in 2021 . The Korean Association of Criminal Procedure Law , 14 (1), pp. 139–198. Web.

Ormerod, D., & Laird, K. (2021). 2. The elements of a crime: Actus reus . Smith, Hogan, and Ormerod’s Criminal Law , pp 26–87. Web.

Rancourt, M. A., Ouellet, C., & Dufresne, Y. (2020). Is the death penalty debate really dead? contrasting capital punishment support in Canada and the United States . Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy , 20 (1), 536–562. Web.

Stetler, R. (2020). The history of mitigation in death penalty cases . Social Work, Criminal Justice, and the Death Penalty , pp. 34–45. Web.

Wheeler, C. H. (2018). Rights in conflict: The clash between abolishing the death penalty and delivering justice to the victims . International Criminal Law Review , 18 (2), 354–375. Web.

Zalewski, W. (2019). Double-track system in Polish criminal law. Political and criminal assumptions, history, contemporary references . Acta Poloniae Historica , 118 , pp 39. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 17). Capital Punishment and the Death Penalty. https://ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-the-death-penalty/

"Capital Punishment and the Death Penalty." IvyPanda , 17 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-the-death-penalty/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Capital Punishment and the Death Penalty'. 17 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Capital Punishment and the Death Penalty." December 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-the-death-penalty/.

1. IvyPanda . "Capital Punishment and the Death Penalty." December 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-the-death-penalty/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Capital Punishment and the Death Penalty." December 17, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-the-death-penalty/.

- Constructive, Reckless and Gross Negligence Manslaughter

- Crimes Against Property, Persons, and Public Order

- Criminal Law, Immunity and Conviction

- Capital Punishment Is Morally and Legally Wrong

- Justifications for Capital Punishment

- The Significance of Capital Punishment in the UAE

- “Dead Man Walking” by Sister Helen Prejean

- The Legality and the Processes of the Death Penalty

5 Death Penalty Essays Everyone Should Know

Capital punishment is an ancient practice. It’s one that human rights defenders strongly oppose and consider as inhumane and cruel. In 2019, Amnesty International reported the lowest number of executions in about a decade. Most executions occurred in China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Egypt . The United States is the only developed western country still using capital punishment. What does this say about the US? Here are five essays about the death penalty everyone should read:

“When We Kill”

By: Nicholas Kristof | From: The New York Times 2019

In this excellent essay, Pulitizer-winner Nicholas Kristof explains how he first became interested in the death penalty. He failed to write about a man on death row in Texas. The man, Cameron Todd Willingham, was executed in 2004. Later evidence showed that the crime he supposedly committed – lighting his house on fire and killing his three kids – was more likely an accident. In “When We Kill,” Kristof puts preconceived notions about the death penalty under the microscope. These include opinions such as only guilty people are executed, that those guilty people “deserve” to die, and the death penalty deters crime and saves money. Based on his investigations, Kristof concludes that they are all wrong.

Nicholas Kristof has been a Times columnist since 2001. He’s the winner of two Pulitizer Prices for his coverage of China and the Darfur genocide.

“An Inhumane Way of Death”

By: Willie Jasper Darden, Jr.

Willie Jasper Darden, Jr. was on death row for 14 years. In his essay, he opens with the line, “Ironically, there is probably more hope on death row than would be found in most other places.” He states that everyone is capable of murder, questioning if people who support capital punishment are just as guilty as the people they execute. Darden goes on to say that if every murderer was executed, there would be 20,000 killed per day. Instead, a person is put on death row for something like flawed wording in an appeal. Darden feels like he was picked at random, like someone who gets a terminal illness. This essay is important to read as it gives readers a deeper, more personal insight into death row.

Willie Jasper Darden, Jr. was sentenced to death in 1974 for murder. During his time on death row, he advocated for his innocence and pointed out problems with his trial, such as the jury pool that excluded black people. Despite worldwide support for Darden from public figures like the Pope, Darden was executed in 1988.

“We Need To Talk About An Injustice”

By: Bryan Stevenson | From: TED 2012

This piece is a transcript of Bryan Stevenson’s 2012 TED talk, but we feel it’s important to include because of Stevenson’s contributions to criminal justice. In the talk, Stevenson discusses the death penalty at several points. He points out that for years, we’ve been taught to ask the question, “Do people deserve to die for their crimes?” Stevenson brings up another question we should ask: “Do we deserve to kill?” He also describes the American death penalty system as defined by “error.” Somehow, society has been able to disconnect itself from this problem even as minorities are disproportionately executed in a country with a history of slavery.

Bryan Stevenson is a lawyer, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, and author. He’s argued in courts, including the Supreme Court, on behalf of the poor, minorities, and children. A film based on his book Just Mercy was released in 2019 starring Michael B. Jordan and Jamie Foxx.

“I Know What It’s Like To Carry Out Executions”

By: S. Frank Thompson | From: The Atlantic 2019

In the death penalty debate, we often hear from the family of the victims and sometimes from those on death row. What about those responsible for facilitating an execution? In this opinion piece, a former superintendent from the Oregon State Penitentiary outlines his background. He carried out the only two executions in Oregon in the past 55 years, describing it as having a “profound and traumatic effect” on him. In his decades working as a correctional officer, he concluded that the death penalty is not working . The United States should not enact federal capital punishment.

Frank Thompson served as the superintendent of OSP from 1994-1998. Before that, he served in the military and law enforcement. When he first started at OSP, he supported the death penalty. He changed his mind when he observed the protocols firsthand and then had to conduct an execution.

“There Is No Such Thing As Closure on Death Row”

By: Paul Brown | From: The Marshall Project 2019

This essay is from Paul Brown, a death row inmate in Raleigh, North Carolina. He recalls the moment of his sentencing in a cold courtroom in August. The prosecutor used the term “closure” when justifying a death sentence. Who is this closure for? Brown theorizes that the prosecutors are getting closure as they end another case, but even then, the cases are just a way to further their careers. Is it for victims’ families? Brown is doubtful, as the death sentence is pursued even when the families don’t support it. There is no closure for Brown or his family as they wait for his execution. Vivid and deeply-personal, this essay is a must-read for anyone who wonders what it’s like inside the mind of a death row inmate.

Paul Brown has been on death row since 2000 for a double murder. He is a contributing writer to Prison Writers and shares essays on topics such as his childhood, his life as a prisoner, and more.

You may also like

16 Inspiring Civil Rights Leaders You Should Know

15 Trusted Charities Fighting for Housing Rights

15 Examples of Gender Inequality in Everyday Life

11 Approaches to Alleviate World Hunger

15 Facts About Malala Yousafzai

12 Ways Poverty Affects Society

15 Great Charities to Donate to in 2024

15 Quotes Exposing Injustice in Society

14 Trusted Charities Helping Civilians in Palestine

The Great Migration: History, Causes and Facts

Social Change 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Rosa Parks: Biography, Quotes, Impact

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Capital Punishment Essay

Essay on Capital Punishment

Capital Punishment is the execution of a person given by the state as a means of Justice for a crime that he has committed. It is a legal course of action taken by the state whereby a person is put to death as a punishment for a crime. There are various methods of capital punishment in order to execute a criminal such as lethal injection, hanging, electrocution, gas chamber, etc. Based on moral and humanitarian grounds, capital punishment is subjected to many controversies not only at the national level but also at the global platform. One must understand the death sentence by itself.

Many records of various civilizations and primal tribal methods denote that the death penalty was a part of their justice system. The system of the prison was evolved to keep people in confinement for some time who have done wrong in their life and was harmful to society. The idea behind keeping the criminal in the prison was to give them a chance to change and reform themselves. The idea works well with people who have done minor offences like theft, robbery, etc. A complication arises when grievous offences like brutal and inhumane acts of rape, murder, mass killing, etc. are involved. So, the contentious part is the grimness of the crime, which is the deciding reason for execution.

During the 20th century period, millions of people died in the wars between the nations or states. In this violent period, military organizations practised capital punishment as a way of maintaining discipline. The death penalty was employed for crimes in many religious beliefs and historically was practised widely with the support of religious hierarchies. Today, there is no religious faith attached to the morality of capital punishment. It has been left to the discretion of the judiciary system to award the punishment in special circumstances.

Most people feel that punishment for crimes like murders, rapes, and mass killings should not be death but some reformative or preventive sentence. The death penalty cannot reform a criminal, since once dead he cannot be reformed. Some people hold the view that no one has the right to take away anyone’s life for any reason. One should not take the role of God in taking away anybody’s life. At the same time, a criminal has no right to take away anyone’s life for any reason at all. If a person could go to an extent of taking someone’s life, he too has no right to live in a civilized society. Both the arguments can be cited to support viewpoints that are poles apart.

Mankind has coined a large number of methods of capital punishment:

hanging by the rope until a person breathes his last.

death by electric current.

the murderer faces a firing squad.

the offender is beheaded and executed.

the culprit is poisoned.

the offender is stoned to death.

he is burnt alive at the stake.

the criminal is made to drown.

the criminal is thrown before hungry beasts of prey.

death through crucifixion.

Guillotine.

the offender is thrown into a poisonous gas chamber.

Methods can be different but all of these methods have one thing common and that is capital punishment is barbaric in all forms. It is savage and vindictive. It is a relic of an uncivilized era. Many people say that the methods by which executions are carried out involve physical torture. Contrary to the popular belief that the death penalty deters all future crimes, various surveys have shown that the threat of the death penalty does not in any way reduce the occurrence of violent crimes.

Capital Punishment in India

Capital punishment in India does not come with a single stoke. The practice of Capital punishment is not very common in India. In our country, the Court of Session awards a death sentence according to the gravity of the offence, and this verdict requires confirmation by the High Court. Then an appeal can be made to the Supreme Court of India. In some cases, an appeal to the Supreme Court lies as a matter of right, where the High Court has reversed the verdict of the Sessions Court either into acquittal or punishment or has enhanced the sentence to capital punishment.

Lastly, if needed an appeal can be made to the president of India and the governors of states for mercy. The President is solely guided by the notes in the files by the Home Minister or the Secretariat. He is bound to pen down the reasons for mercy. It is exercised very judiciously.

Contemplating over capital punishment has been ramping on for a countless number of years. It is true that the death sentence is not the solution to the increase in crimes but at the same time, capital punishment inflicts physiological fear in the minds of people. In many countries, the use of this punishment has helped to deter crimes and change the minds of future criminals against committing heinous crimes. Capital punishment should be given in the rare of the rarest cases after proper investigation of the criminal’s offence.

FAQs on Capital Punishment Essay

Q1. What Do You Understand By Capital Punishment?

Ans. Capital Punishment is the execution of a person given by the state as a means of Justice for a crime that he has committed. It is a legal course of action taken by the state whereby a person is put to death as a punishment for a crime. There are quite a few methods of capital punishment to execute a criminal such as lethal injection, hanging, electrocution, gas chamber, etc.

Q2. Why Do Some People Argue Against Capital Punishment?

Ans. Some people argue against capital punishment because they hold the view that no one other than God has the right to take anyone’s life. They argue that criminals should get a chance to change or reform themselves into good and responsible human beings. If they are executed, then they cannot be reformed.

Q3. What are Some Methods that Mankind has Coined for Capital Punishment?

Ans. Mankind has coined various methods of capital punishment:

the criminal is burnt alive at the stake.

the offender is thrown before hungry beasts of prey.

Q4. Does Capital Punishment Deter the Rate of Crimes?

Ans. There is no solid evidence to the theory of capital punishment that it reduces the crime rate but yes it does instil psychological fear in the minds of future criminals against committing heinous crimes.

Death Penalty - Essay Samples And Topic Ideas For Free

The death penalty, also known as capital punishment, remains a contentious issue in many societies. Essays on this topic could explore the moral, legal, and social arguments surrounding the practice, including discussions on retribution, deterrence, and justice. They might delve into historical trends in the application of the death penalty, the potential for judicial error, and the disparities in its application across different demographic groups. Discussions might also explore the psychological impact on inmates, the families involved, and the society at large. They could also analyze the global trends toward abolition or retention of the death penalty and the factors influencing these trends. A substantial compilation of free essay instances related to Death Penalty you can find at Papersowl. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Death Penalty and Justice

By now, many of us are familiar with the statement, "an eye for an eye," which came from the bible, so it should be followed as holy writ. Then there was Gandhi, who inspired thousands and said, "an eye for an eye will leave us all blind." This begs the question, which option do we pick to be a good moral agent, in the terms of justice that is. Some states in America practice the death penalty, where some states […]

The Controversy of Death Penalty

The death penalty is a very controversial topic in many states. Although the idea of the death penalty does sound terrifying, would you really want a murderer to be given food and shelter for free? Would you want a murderer to get out of jail and still end up killing another innocent person? Imagine if that murder gets out of jail and kills someone in your family; Wouldn’t you want that murderer to be killed as well? Murderers can kill […]

Stephen Nathanson’s “An Eye for an Eye”

According to Stephen Nathanson's "An Eye for an Eye?", he believes that capital punishment should be immediately abolished and that the principle of punishment, "lex talionis" which correlates to the classic saying "an eye for an eye" is not a valid reason for issuing the death penalty in any country, thus, abolishment of Capital Punishment should follow. Throughout the excerpt from his book, Nathanson argues against this principle believing that one, it forces us to "commit highly immoral actions”raping a […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

Does the Death Penalty Effectively Deter Crime?

The death penalty in America has been effective since 1608. Throughout the years following the first execution, criminal behaviors have begun to deteriorate. Capital punishment was first formed to deter crime and treason. As a result, it increased the rate of crime, according to researchers. Punishing criminals by death does not effectively deter crime because criminals are not concerned with consequences, apprehension, and judges are not willing to pay the expenses. During the stage of mens rea, thoughts of committing […]

The Death Penalty: Right or Wrong?

The death penalty has been a controversial topic throughout the years and now more than ever, as we argue; Right or Wrong? Moral or Immoral? Constitutional or Unconstitutional? The death penalty also known as capital punishment is a legal process where the state justice sentences an individual to be executed as punishment for a crime committed. The death penalty sentence strongly depends on the severity of the crime, in the US there are 41 crimes that can lead to being […]

About Carlton Franklin

In most other situations, the long-unsolved Westfield Murder would have been a death penalty case. A 57-year-old legal secretary, Lena Triano, was found tied up, raped, beaten, and stabbed in her New Jersey home. A DNA sample from her undergarments connected Carlton Franklin to the scene of the crime. However, fortunately enough for Franklin, he was not convicted until almost four decades after the murder and, in an unusual turn of events, was tried in juvenile court. Franklin was fifteen […]

About the Death Penalty

The death penalty has been a method used as far back as the Eighteenth century B.C. The use of the death penalty was for punishing people for committing relentless crimes. The severity of the punishment were much more inferior in comparison to modern day. These inferior punishments included boiling live bodies, burning at the stake, hanging, and extensive use of the guillotine to decapitate criminals. In the ancient days no laws were established to dictate and regulate the type of […]

The Death Penalty should not be Legal

Imagine you hit your sibling and your mom hits you back to teach that you shouldn't be hitting anyone. Do you really learn not to be violent from that or instead do you learn how it is okay for moms or dads to hit their children in order to teach them something? This is exactly how the death penalty works. The death penalty has been a form of punishment for decades. There are several methods of execution and those are […]

Effectively Solving Society’s Criminality

Has one ever wondered if the person standing or sitting next to them has the potential to be a murderer or a rapist? What do those who are victimized personally or have suffered from a tragic event involving a loved-one or someone near and dear to their heart, expect from the government? Convicted felons of this nature and degree of unlawfulness should be sentenced to death. Psychotic killers and rapists need the ultimate consequences such as the death penalty for […]

Religious Values and Death Penalty

Religious and moral values tell us that killing is wrong. Thou shall not kill. To me, the death penalty is inhumane. Killing people makes us like the murderers that most of us despise. No imperfect system should have the right to decide who lives and who dies. The government is made up of imperfect humans, who make mistakes. The only person that should be able to take life, is god. "An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind". […]

Abolishment of the Death Penalty

Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to relate many different criminological theories in regard to capital punishment. We relate many criminological theories such as; cognitive theory, deviant place theory, latent trait theory, differential association theory, behavioral theory, attachment theory, lifestyle theory, and biosocial theory. This paper empirically analyzes the idea that capital punishment is inhumane and should be abolished. We analyze this by taking into consideration false convictions, deterrence of crime, attitudes towards capital punishment, mental illness and juvenile […]

Punishment and the Nature of the Crime

When an individual commits a crime then he/she is given punishment depending on the nature of the crime committed. The US's way of giving punishment to an offender has been criticized for many years. There are 2 types of cases; civil and criminal cases. In civil cases, most of the verdict comprises of jail time or fine amount to be paid. These are not as severe except the one related to money laundering and forgery. On the other hand, criminal […]

The Death Penalty and Juveniles

Introduction: In today's society, many juveniles are being sent to trial without having the chance of getting a fair trial as anyone else would. Many citizens would see juveniles as dangerous individuals, but in my opinion how a teenager acts at home starts at home. Punishing a child for something that could have been solved at home is something that should not have to get worse by giving them the death penalty. The death penalty should not be imposed on […]

Is the Death Penalty “Humane”

What’s the first thing that pops up in your mind when you hear the words Capital Punishment? I’m assuming for most people the first thing that pops up is a criminal sitting on a chair, with all limbs tied down, and some type of mechanism connected to their head. Even though this really isn't the way that it is done, I do not blame people for imagining that type of image because that is how movies usually portray capital punishment. […]

Euthanasia and Death Penalty

Euthanasia and death penalty are two controversy topics, that get a lot of attention in today's life. The subject itself has the roots deep in the beginning of the humankind. It is interesting and maybe useful to learn the answer and if there is right or wrong in those actions. The decision if a person should live or die depends on the state laws. There are both opponents and supporters of the subject. However different the opinions are, the state […]

The Death Penalty is not Worth the Cost

The death penalty is a government practice, used as a punishment for capital crimes such as treason, murder, and genocide to name a few. It has been a controversial topic for many years some countries still use it while others don't. In the United States, each state gets to choose whether they consider it to be legal or not. Which is why in this country 30 states allow it while 20 states have gotten rid of it. It is controversial […]

Ineffectiveness of Death Penalty

Death penalty as a means of punishing crime and discouraging wrong behaviour has suffered opposition from various fronts. Religious leaders argue that it is morally wrong to take someone's life while liberal thinkers claim that there are better ways to punish wrong behaviour other than the death penalty. This debate rages on while statistically, Texas executes more individuals than any other state in the United States of America. America itself also has the highest number of death penalty related deaths […]

Is the Death Penalty Morally Right?

There have been several disputes on whether the death penalty is morally right. Considering the ethical issues with this punishment can help distinguish if it should be denied or accepted. For example, it can be argued that a criminal of extreme offenses should be granted the same level of penance as their crime. During the duration of their sentencing they could repent on their actions and desire another opportunity of freedom. The death penalty should be outlawed because of too […]

Why the Death Penalty is Unjust

Capital punishment being either a justifiable law, or a horrendous, unjust act can be determined based on the perspective of different worldviews. In a traditional Christian perspective, the word of God given to the world in The Holy Bible should only be abided by. The Holy Bible states that no man (or woman) should shed the blood of another man (or woman). Christians are taught to teach a greater amount of sacrifice for the sake of the Lord. Social justice […]

The Death Penalty and People’s Opinions

The death penalty is a highly debated topic that often divided opinion amongst people all around the world. Firstly, let's take a look at our capital punishments, with certain crimes, come different serving times. Most crimes include treason, espionage, murder, large-scale drug trafficking, and murder towards a juror, witness, or a court officer in some cases. These are a few examples compared to the forty-one federal capital offenses to date. When it comes to the death penalty, there are certain […]

The Debate of the Death Penalty

Capital punishment is a moral issue that is often scrutinized due to the taking of someone’s life. This is in large part because of the views many have toward the rule of law or an acceptance to the status quo. In order to get a true scope of the death penalty, it is best to address potential biases from a particular ethical viewpoint. By looking at it from several theories of punishment, selecting the most viable theory makes it a […]

The History of the Death Penalty

The History of the death penalty goes as far back as ancient China and Babylon. However, the first recorded death sentence took place in 16th Century BC Egypt, where executions were carried out with an ax. Since the very beginning, people were treated according to their social status; those wealthy were rarely facing brutal executions; on the contrary, most of the population was facing cruel executions. For instance, in the 5th Century BC, the Roman Law of the Twelve Tablets […]

Death Penalty is Immoral

Let's say your child grabs a plate purposely. You see them grab the plate, smash it on the ground and look you straight in the eyes. Are they deserving of a punishment? Now what if I say your child is three years old. A three year old typically doesn't know they have done something wrong. But since your child broke that one plate, your kid is being put on death row. You may be thinking, that is too harsh of […]

The Death Penalty in the United States

The United States is the "land of the free, home of the brave" and the death penalty (American National Anthem). Globally, America stands number five in carrying executions (Lockie). Since its resurrection in 1976, the year in which the Supreme Court reestablished the constitutionality of the death penalty, more than 1,264 people have been executed, predominantly by the medium of lethal injection (The Guardian). Almost all death penalty cases entangle the execution of assassins; although, they may also be applied […]

Cost of the Death Penalty

The death penalty costs more than life in prison. According to Fox News correspondent Dan Springer, the State of California spent 4 billion dollars to execute 13 individuals, in addition to the net spend of an estimated $64,000 per prisoner every year. Springer (2011) documents how the death penalty convictions declined due to economic reasons. The state spends up to 3 times more when seeking a death penalty than when pursuing a life in prison without the possibility of parole. […]

The Solution to the Death Penalty

There has never been a time when the United States of America was free from criminals indulging in killing, stealing, exploiting people, and even selling illegal items. Naturally, America refuses to tolerate the crimes committed by those who view themselves as above the law. Once these convicts are apprehended, they are brought to justice. In the past, these criminals often faced an ultimate punishment: the death penalty. Mercy was a foreign concept due to their underdeveloped understanding of the value […]

Costs: Death Penalty Versus Prison Costs

The Conservatives Concerned Organization challenges the notion that the death penalty is more cost effective compared to prison housing and feeding costs. The organization argues that the death penalty is an expensive lengthy and complicated process concluding that it is not only a bloated program that delays justice and bogs down the enforcement of the law, it is also an inefficient justice process that diverts financial resources from law enforcement programs that could protect individuals and save lives. According to […]

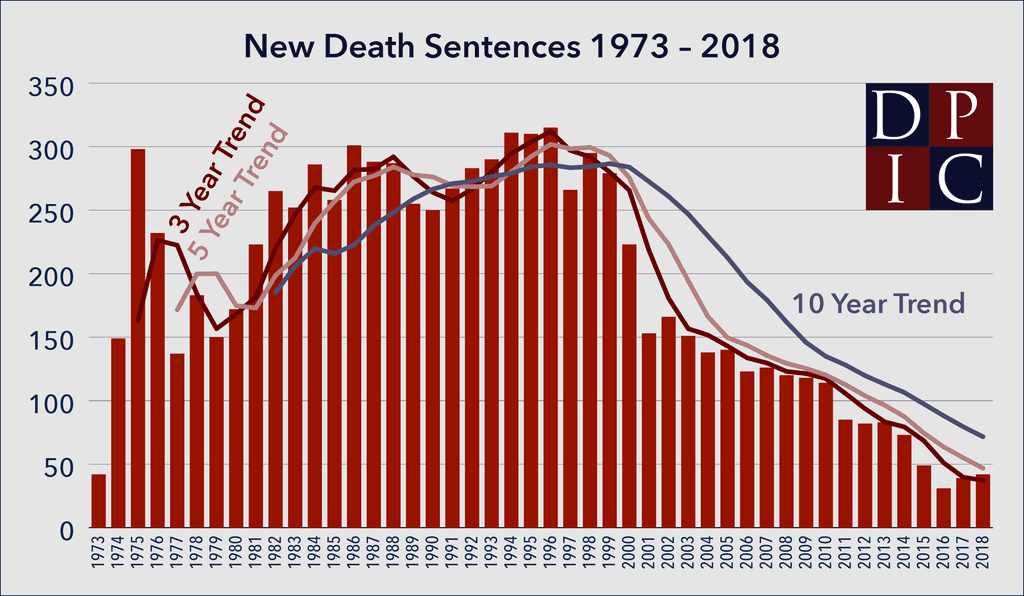

Death Penalty as a Source of Constant Controversy

The death penalty has been a source of almost constant controversy for hundreds of years, splitting the population down the middle with people supporting the death penalty and people that think it is unnecessary. The amount of people that are been against the death penalty has grown in recent years, causing the amount of executions to dwindle down to where there is less than one hundred every year. This number will continue to lessen as more and more people decide […]

Death Penalty is Politically Just?

Being wrongfully accused is unimaginable, but think if you were wrongfully accused and the ultimate punishment was death. Death penalty is one of the most controversial issues in today's society, but what is politically just? When a crime is committed most assume that the only acceptable consequence is to be put to death rather than thinking of another form of punishment. Religiously the death penalty is unfair because the, "USCCB concludes prisoners can change and find redemption through ministry outreach, […]

George Walker Bush and Death Penalty

George Walker Bush, a former U.S. president, and governor of Texas, once spoke, "I don't think you should support the death penalty to seek revenge. I don't think that's right. I think the reason to support the death penalty is because it saves other people's lives." The death penalty, or capital punishment, refers to the execution of a criminal convicted of a capital offense. With many criminals awaiting execution on death row, the death penalty has been a debated topic […]

Additional Example Essays

- Death Penalty Should be Abolished

- Main Reasons of Seperation from Great Britain

- Leadership and the Army Profession

- Letter From Birmingham Jail Rhetorical Analysis

- Why Abortion Should be Illegal

- Logical Fallacies in Letter From Birmingham Jail

- How the Roles of Women and Men Were Portrayed in "A Doll's House"

- Ethical or Unethical Behavior in Business

- Does Arrest Reduce Domestic Violence

- Recycling Should be Mandatory

- Why I Want to Be an US Army Officer

How To Write an Essay About Death Penalty

Understanding the topic.

When writing an essay about the death penalty, the first step is to understand the depth and complexities of the topic. The death penalty, also known as capital punishment, is a legal process where a person is put to death by the state as a punishment for a crime. This topic is highly controversial and evokes strong emotions on both sides of the debate. It's crucial to approach this subject with sensitivity and a balanced perspective, acknowledging the moral, legal, and ethical considerations involved. Research is key in this initial phase, as it's important to gather facts, statistics, and viewpoints from various sources to have a well-rounded understanding of the topic. This foundation will set the tone for your essay, guiding your argument and supporting your thesis.

Structuring the Argument

The next step is structuring your argument. In an essay about the death penalty, it's vital to present a clear thesis statement that outlines your stance on the issue. Are you for or against it? What are the reasons behind your position? The body of your essay should then systematically support your thesis through well-structured arguments. Each paragraph should focus on a specific aspect of the death penalty, such as its ethical implications, its effectiveness as a deterrent to crime, or the risk of wrongful convictions. Ensure that each point is backed up by evidence and examples, and remember to address counterarguments. This not only shows that you have considered multiple viewpoints but also strengthens your position by demonstrating why these opposing arguments may be less valid.

Exploring Ethical and Moral Dimensions

An essential aspect of writing an essay on the death penalty is exploring its ethical and moral dimensions. This involves delving into philosophical debates about the value of human life, justice, and retribution. It's important to discuss the moral justifications that are often used to defend the death penalty, such as the idea of 'an eye for an eye,' and to critically evaluate these arguments. Equally important is exploring the ethical arguments against the death penalty, including the potential for innocent people to be executed and the question of whether the state should have the power to take a life. This section of the essay should challenge readers to think deeply about their values and the principles of a just society.

Concluding Thoughts

In conclusion, revisit your thesis and summarize the key points made in your essay. This is your final opportunity to reinforce your argument and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Discuss the broader implications of the death penalty in society and consider potential future developments in this area. You might also want to offer recommendations or pose questions that encourage further reflection on the topic. Remember, a strong conclusion doesn't just restate what has been said; it provides closure and offers new insights, prompting readers to continue thinking about the subject long after they have finished reading your essay.

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Home — Essay Samples — Philosophy — Ethical Dilemma — The Morality of Capital Punishment: Is It Ethical

The Morality of Capital Punishment: is It Ethical

- Categories: Capital Punishment Ethical Dilemma

About this sample

Words: 678 |

Published: Sep 12, 2023

Words: 678 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Arbitrary application of the death penalty, risk of executing innocent individuals, failure as a deterrent to crime, the ethical alternative: life imprisonment.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues Philosophy

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1600 words

4 pages / 1866 words

1 pages / 598 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Ethical Dilemma

Social dilemmas happen when the members of a group, culture, or society are in possible conflict over the establishment and use of shared “public goods”. Public goods are benefits that are shared by a community and that everyone [...]

In this scenario, the primary stakeholders are the employees, which in turn affect the customers, the shareholders, the suppliers, and the community. If Roger Jacobs is allowed to remain at Shellington Pharmaceuticals and [...]

There are four main sources of law within the legal system of the United States. These include Statutes, Case Law (Judicial), Constitution and Administrative Regulations. Within the source of laws under Statutes, it includes [...]

sheds light on the detrimental impact of social media on society, revealing how developers and owners exploit users through data mining and surveillance technologies (Orlowski, 2020). The addictive nature of social media [...]

Social workers will come across ethical dilemmas on a regular basis. Ethical dilemmas may include inappropriate nature in the workplace, or having to make a decision that may go against protocols but be morally the right thing [...]

Ethical dilemma is a decision between two alternatives, both of which will bring an antagonistic outcome in light of society and individual rules. It is a basic leadership issue between two conceivable good objectives, neither [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Human Rights Practice

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Imperatives, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

A Factful Perspective on Capital Punishment

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David T Johnson, A Factful Perspective on Capital Punishment, Journal of Human Rights Practice , Volume 11, Issue 2, July 2019, Pages 334–345, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huz018

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Substantial progress has been made towards worldwide abolition of capital punishment, and there are good reasons to believe that more progress is possible. Since 2000, the pace of abolition has slowed, but by several measures the number of executions in the world has continued to decline. Several causes help explain the decline, including political leadership from the front and an increased tendency to regard capital punishment as a human rights issue rather than as a matter of domestic criminal justice policy. There are significant obstacles in the movement to eliminate state killing in the world, but some strategies could contribute to additional decline in the years to come.

People tend to notice the bad more than the good, and this ‘negativity instinct’ is apparent when it comes to capital punishment ( Rosling et al. 2018 : 48). For example, two decades ago, Leon Radzinowicz (1999 : 293), the founder of Cambridge University’s Institute of Criminology, declared that he ‘did not expect any substantial further decrease’ in the use of capital punishment because ‘most of the countries likely to embrace the abolitionist cause’ had already done so. In more recent years, other analysts have claimed that the human rights movement is in crisis, and that ‘nearly every country seems to be backsliding’ ( Moyn 2018 ). If this assessment is accurate, it should be cause for concern for opponents of capital punishment because a heightened regard for human rights is widely regarded as the key cause of abolition since the 1980s ( Hood and Hoyle 2009 ).

To be sure, everything is not fine with respect to capital punishment. Most notably, the pace of abolition has slowed in recent years, and executions have increased in several countries, including Iran and Taiwan (in the 2010s), Pakistan (2014–15), and Japan (2018). But too much negativity will not do. I adopt a factful perspective about the future of capital punishment: I see substantial progress toward worldwide abolition, and this gives me hope that further progress is possible ( Rosling et al. 2018 ).

This article builds on Roger Hood’s seminal study of the movement to abolish capital punishment, which found ‘a remarkable increase in the number of abolitionist countries’ in the 1980s and 1990s ( Hood 2001 : 331). It proceeds in four parts. Section 1 shows that in the two decades or so since 2000 the pace of abolition has slowed but not ceased, and the total number of executions in the world has continued to decline. Section 2 explains how death penalty declines have been achieved in recent years. Section 3 identifies obstacles in the movement toward elimination of state killing in the modern world. And Section 4 suggests some priorities and strategies that could contribute to additional decline in the death penalty in the third decade of the third millennium.

These examples exclude estimates for the People’s Republic of China, which does not disclose reliable death penalty figures, but which probably executes more people each year than the rest of the world combined.

Table 1 displays the number of countries with each of these four death penalty statuses in five years: 1988, 1995, 2000, 2007, and 2017. Overall, the percentage of countries to retain capital punishment has declined by half over that period, from 56 per cent in 1988 to 28 per cent in 2017. But Table 2 shows that the pace of abolition has slowed since the 1990s, when 37 countries abolished. By comparison, only 23 countries abolished in the 2000s, with 11 more countries abolishing in the first eight years of the 2010s. The pace of abolition has declined partly because much of the lowest hanging fruit has already been picked.

Number of abolitionist and retentionist countries, 1988–2017

Note : Figures in parentheses show the percentage of the total number of countries in the world in that year.

Sources : Hood 2001 : 334 (for 1988, 1995, and 2000); Amnesty International annual reports (for 2007 and 2017).

Number of Countries That Abolished the Death Penalty by Decade, 1980s – 2010s

Sources : Death Penalty Information Center; Amnesty International annual reports.

Table 3 uses Hood’s figures for 1980 to 1999 ( Hood 2001 : 335) and figures from Hands Off Cain and Amnesty International to report the estimated number of executions and death sentences worldwide from 1980 to 2017. Because several countries (including China, the world’s leading user of capital punishment) do not disclose reliable death penalty statistics, the figures in Table 3 cannot be considered precise measures of death sentencing and execution trends over time, but the numbers do suggest recent declines. For instance, the average number of death sentences per year in the 2010s (2,220) was less than half the annual average for the 2000s (4,576). Similarly, the average number of executions per year in the 2010s (867) was less than half the annual average for the 2000s (1,762). Moreover, while the average number of countries per year to impose a death sentence remained fairly flat in the four decades covered in Table 3 (58 countries in the 1980s, 68 in the 1990s, 56 in the 2000s, and 58 in the 2010s), the average number of countries per year which carried out an execution declined by about one-third, from averages of 37 countries in the 1980s and 35 countries in the 1990s, to 25 countries in the 2000s and 23 countries in the 2010s. In short, fewer countries are using capital punishment, and fewer people are being condemned to death and executed.

Number of death sentences and executions worldwide, 1980–2017

Notes : (a) The numbers of reported and recorded death sentences and executions are minimum figures, and the true totals are substantially higher. (b) In 2009, Amnesty International stopped publishing estimates of the minimum number of executions per year in China.

Sources : Hood 2001 : 335 (1980–1999); Hands Off Cain (2001); Amnesty International annual reports (2002–2017).

In 2001, Hood (2001 : 336) reported that 26 countries had executed at least 20 persons in the five-year period 1994–1998. Table 4 compares those figures with figures for the same 26 countries in 2013–2017, and it also presents the annual rate of execution per million population for each country (in parentheses). The main pattern is striking decline. In 2009, Amnesty International stopped publishing estimates of the minimum number of executions per year in the People’s Republic of China, so trend evidence from that source is unavailable, but other sources indicate that executions in China have declined dramatically in the past two decades, from 15,000 or more per year in the late 1990s and early 2000s ( Johnson and Zimring 2009 : 237), to approximately 2,400 in 2013 ( Grant 2014 ) and 2,000 or so in 2016. Of the other 25 countries in Hood’s list of heavy users of capital punishment in the 1990s, 11 saw executions disappear (Ukraine, Turkmenistan, Russia, Kazakhstan, Congo, Sierra Leone, Kyrgyzstan, South Korea, Libya, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe), eight had the execution rate decline by half or more (USA, Nigeria, Singapore, Belarus, Taiwan, Yemen, Jordan, Afghanistan), and two experienced more modest declines (Saudi Arabia and Egypt). Altogether, 22 of the 26 heavy users of capital punishment in the latter half of the 1990s have experienced major declines in executions. Of the remaining four countries, one (Japan) saw its execution rate remain stable until executions surged when 13 former members of Aum Shinrikyo were hanged in July 2018 (for murders and terrorist attacks committed in the mid-1990s), while three (Iran, Pakistan, and Viet Nam) experienced sizeable increases in both executions and execution rates.

Executions and execution rates by country, 1994–1998 and 2013–2017

a The figure of 429 executions for Viet Nam is for the three years from August 2013 to July 2016.

Notes: Countries reported to have executed at least 20 persons in 1994–1998, and execution figures for the same countries in 2013–2017 (with annual rates of execution per million population for both periods in parentheses).

As explained in the text, in addition to the 26 countries that appeared in Table 3 of Hood (2001 : 336), India had at least 24 judicial executions in 1994–1998, Indonesia had four, and Iraq had an unknown number. The comparable figures for these countries in 2013–2017 (with the execution rate per million population in parentheses) are India = 2 (0.0003), Indonesia = 23 (0.09), and Iraq = 469 (2.78).

Sources : Hood 2001 : 336 (1994–1998); Amnesty International (2013–2017); the Death Penalty Database of the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide (for India, Indonesia, and Iraq); Johnson and Zimring 2009 : 430 (for India 1994–1998).

The execution rate increases in Table 4 are striking but exceptional. In Iran, the fourfold increase in the execution rate gives it the highest per capita execution rate in the world for 2013–2017, with 6.68 executions per million population per year. This is approximately four times higher than the estimated execution rate for China (1.5) in the same period. The increase in Viet Nam is also fourfold, from 0.38 executions per million population per year to 1.5, while the increase in Pakistan is tenfold, from 0.05 to 0.49. Nonetheless, Viet Nam’s substantially increased execution rate in the 2010s would not have ranked it among the top ten executing nations in the 1990s, while Pakistan’s increased rate in the 2010s would not have ranked it among the top 15 nations in the 1990s. Even among the heaviest users of capital punishment, times have changed.

At least two countries that did not appear on Hood’s heavy user list for the 1990s executed more than 20 people in 2013–2017. The most notable newcomer is Iraq, which executed at least 469 persons in this five-year period, with an execution rate of 2.78 per million population per year. And then there is Indonesia. In the five years from 1994 to 1998, this country (with the world’s largest Muslim population) executed a total of four people, while in 2013–2017 the number increased to 23, giving it an execution rate of 0.09 per year per million population—about the same as the (low) execution rates in Japan and Taiwan.

When Iraq and Indonesia are added to the heavy user list for 2013–2017, only five countries out of 28 have execution rates that exceed one execution per year per million population, giving them death penalty systems that can be deemed ‘operational’ in the sense that ‘judicial executions are a recurrent and important part’ of their criminal justice systems ( Johnson and Zimring 2009 : 22). By contrast, in 1994–1998, 14 of these 28 countries had death penalty systems that were ‘operational’.

India is a country with a large population that does not appear on the frequent executing list for either the 1990s or the 2010s. In 2013–2017, this country of 1.3 billion people executed only two people, giving it what is probably the lowest execution rate (0.0003) among the 56 countries that currently retain capital punishment. India has long used judicial execution infrequently, but its police and security forces continue to kill in large numbers. In the 22 years from 1996 through 2017, India’s legal system hanged only four people, giving it an annual rate of execution that is around 1/25,000th the rate of executions in China. But over the same period, India’s police and security forces have killed thousands illegally and extrajudicially, many in ‘encounters’ that officials try to justify with the lie that the bad guy fired first.

Two fundamental forces have been driving the death penalty down in recent decades ( Johnson and Zimring 2009 : 290–304). First, while prosperity is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for abolition, economic development does tend to encourage declines in judicial execution and steps toward the cessation of capital punishment. Second, the general political orientation of government often has a strong influence on death penalty policy, at both ends of the execution spectrum. High-execution rate nations tend to be authoritarian, as in China, Viet Nam, North Korea, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq. Conversely, low-execution rate nations tend to be democracies with institutionalized limits on governmental power, as in most of the countries of Europe and in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Korea, and India. Of course, these are tendencies, not natural laws. Exceptions exist, including the USA at the high end of the execution spectrum, and Myanmar and Nepal at the low end.

In addition to economic development and democratization, concerns about wrongful convictions and the execution of innocents have made some governments more cautious about capital punishment. In the USA, for example, the discovery of innocence has led to historic shifts in public opinion and to sharp declines in the use of capital punishment by prosecutors and juries across the country ( Baumgartner et al. 2008 ; Garrett 2017 ). In China, too, wrongful convictions and executions help explain both declines in the use of capital punishment and legal reforms of the institution ( He 2016 ).

The question of capital punishment is fundamentally a matter of human rights, not an isolated issue of criminal justice policy.

Death penalty policy should not be governed by national priorities but by adherence to international human rights standards.

Since capital punishment is never justified, a national government may demand that other nations’ governments end executions. ( Zimring 2003 : 27)

As the third premise of this orthodoxy suggests, political pressure has contributed to the decline of capital punishment. This influence has been especially striking in Europe, where abolition of capital punishment is an explicit and absolute condition for becoming a member of the European Union. In other countries, too, from Singapore and South Korea to Rwanda and Sierra Leone, the missionary zeal of European governments committed to abolition has led to the elimination of capital punishment or to major declines in its usage.

Political leadership has also fostered the death penalty’s decline. There are few iron rules of abolition, but one seems to be that when the death penalty is eliminated, it invariably happens despite the fact of majority public support for the institution at the time of abolition. This—‘leadership from the front’—is such a common pattern, and public resistance to abolition is so stubborn, that some analysts believe ‘the straightest road to abolition involves bypassing public opinion entirely’ ( Hammel 2010 : 236). There appear to be at least two political circumstances in which the likelihood of leadership from the front rises and the use of capital punishment falls ( Zimring 2003 : 22): after the collapse of an authoritarian government, when new leaders aim to distance themselves from the repressive practices of the previous regime (as in West Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Romania, Cambodia, and Timor Leste); and after a left-liberal party gains control of government (as in Austria, Great Britain, France, South Korea, and Taiwan).

Although use of the death penalty continues to decline, there are countervailing forces that continue to present obstacles to abolition, as they have for decades. First and foremost, there is an argument about national sovereignty made by many states, that death penalty policy and practice are not human rights issues but rather matters of criminal justice policy that should be decided domestically, according to the values and traditions of each individual country. There is the role of religion—especially Islamic beliefs, where in some countries and cultures it is held that capital punishment must not be opposed because it has been divinely ordained. There are claims that capital punishment deters criminal behaviour and drug trafficking, though there is little evidence to support this view ( National Research Council 2012 ; Muramatsu et al. 2018 ). And there is the continued use of capital punishment in the USA, which helps to legitimate capital punishment in other countries ( Hood 2001 : 339–44).

The death penalty also survives in some places because it performs welcome functions for some interests. For instance, following the Arab Spring movements of 2010–2012, Egypt and other Middle Eastern governments employed capital punishment against many anti-government demonstrators and dissenters. In other retentionist countries, capital punishment has little to do with its instrumental value for government and crime control and much to do with the fact that it is ‘productive, performative, and generative—that it makes things happen—even if much of what happens is in the cultural realm of death penalty discourse rather than the biological realm of life and death’ or the penological realms of retribution and deterrence ( Garland 2010 : 285). For elected officials, the death penalty is a political token to be used in electoral contests. For prosecutors and judges, it is a practical instrument that enables them to harness the rhetorical power of death in the pursuit of professional objectives. For the mass media, it is an arena in which dramas can be narrated about the human condition. And for the onlooking public, it is a vehicle for moral outrage and an opportunity for prurient entertainment.

In addition to these long-standing obstacles to abolition, several other impediments have emerged in recent years. Most notably, as populism spreads ( Luce 2017 ) and democracy declines in many parts of the world ( Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018 ), an ‘anti-human rights agenda’ is forcing human rights proponents to rethink their assumptions and re-evaluate their strategies ( Alston 2017 ). Much of the new populist threat to democracy is linked to post-9/11 concerns about terrorism, which have been exploited to justify trade-offs between democracy and security. Of course, we are not actually living in a new age of terrorism. If anything, we have experienced a decline in terrorism from the decades in which it was less of a big deal in our collective consciousness ( Pinker 2011 : 353). But emotionally and rhetorically, terrorism is very much a big deal in the present moment, and the cockeyed ratio of fear to harm that is fostered by its mediated representations has been used to buttress support for capital punishment in many countries, including the USA (the Oklahoma City bombings in 1995), Japan (the sarin gas attacks of 1994 and 1995), China (in Xinjiang and Tibet), India (the Mumbai attacks of 1993 and 2008 and the 2001 attack on the Parliament in New Delhi), and Iraq (where executions surged after the post-9/11 invasion by the USA, and where most persons executed have been convicted of terrorism). More broadly, the present political resonance of terrorism has resulted in some abolitionist states assisting with the use of capital punishment in retentionist nations ( Malkani 2013 ).