Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

How to Write a Lab Report – with Example/Template

April 11, 2024

Perhaps you’re in the midst of your challenging AP chemistry class in high school, or perhaps college you’re enrolled in biology , chemistry , or physics at university. At some point, you will likely be asked to write a lab report. Sometimes, your teacher or professor will give you specific instructions for how to format and write your lab report, and if so, use that. In case you’re left to your own devices, here are some guidelines you might find useful. Continue reading for the main elements of a lab report, followed by a detailed description of the more writing-heavy parts (with a lab report example/lab report template). Lastly, we’ve included an outline that can help get you started.

What is a lab report?

A lab report is an overview of your experiment. Essentially, it explains what you did in the experiment and how it went. Most lab reports end up being 5-10 pages long (graphs or other images included), though the length depends on the experiment. Here are some brief explanations of the essential parts of a lab report:

Title : The title says, in the most straightforward way possible, what you did in the experiment. Often, the title looks something like, “Effects of ____ on _____.” Sometimes, a lab report also requires a title page, which includes your name (and the names of any lab partners), your instructor’s name, and the date of the experiment.

Abstract : This is a short description of key findings of the experiment so that a potential reader could get an idea of the experiment before even beginning.

Introduction : This is comprised of one or several paragraphs summarizing the purpose of the lab. The introduction usually includes the hypothesis, as well as some background information.

Lab Report Example (Continued)

Materials : Perhaps the simplest part of your lab report, this is where you list everything needed for the completion of your experiment.

Methods : This is where you describe your experimental procedure. The section provides necessary information for someone who would want to replicate your study. In paragraph form, write out your methods in chronological order, though avoid excessive detail.

Data : Here, you should document what happened in the experiment, step-by-step. This section often includes graphs and tables with data, as well as descriptions of patterns and trends. You do not need to interpret all of the data in this section, but you can describe trends or patterns, and state which findings are interesting and/or significant.

Discussion of results : This is the overview of your findings from the experiment, with an explanation of how they pertain to your hypothesis, as well as any anomalies or errors.

Conclusion : Your conclusion will sum up the results of your experiment, as well as their significance. Sometimes, conclusions also suggest future studies.

Sources : Often in APA style , you should list all texts that helped you with your experiment. Make sure to include course readings, outside sources, and other experiments that you may have used to design your own.

How to write the abstract

The abstract is the experiment stated “in a nutshell”: the procedure, results, and a few key words. The purpose of the academic abstract is to help a potential reader get an idea of the experiment so they can decide whether to read the full paper. So, make sure your abstract is as clear and direct as possible, and under 200 words (though word count varies).

When writing an abstract for a scientific lab report, we recommend covering the following points:

- Background : Why was this experiment conducted?

- Objectives : What problem is being addressed by this experiment?

- Methods : How was the study designed and conducted?

- Results : What results were found and what do they mean?

- Conclusion : Were the results expected? Is this problem better understood now than before? If so, how?

How to write the introduction

The introduction is another summary, of sorts, so it could be easy to confuse the introduction with the abstract. While the abstract tends to be around 200 words summarizing the entire study, the introduction can be longer if necessary, covering background information on the study, what you aim to accomplish, and your hypothesis. Unlike the abstract (or the conclusion), the introduction does not need to state the results of the experiment.

Here is a possible order with which you can organize your lab report introduction:

- Intro of the intro : Plainly state what your study is doing.

- Background : Provide a brief overview of the topic being studied. This could include key terms and definitions. This should not be an extensive literature review, but rather, a window into the most relevant topics a reader would need to understand in order to understand your research.

- Importance : Now, what are the gaps in existing research? Given the background you just provided, what questions do you still have that led you to conduct this experiment? Are you clarifying conflicting results? Are you undertaking a new area of research altogether?

- Prediction: The plants placed by the window will grow faster than plants placed in the dark corner.

- Hypothesis: Basil plants placed in direct sunlight for 2 hours per day grow at a higher rate than basil plants placed in direct sunlight for 30 minutes per day.

- How you test your hypothesis : This is an opportunity to briefly state how you go about your experiment, but this is not the time to get into specific details about your methods (save this for your results section). Keep this part down to one sentence, and voila! You have your introduction.

How to write a discussion section

Here, we’re skipping ahead to the next writing-heavy section, which will directly follow the numeric data of your experiment. The discussion includes any calculations and interpretations based on this data. In other words, it says, “Now that we have the data, why should we care?” This section asks, how does this data sit in relation to the hypothesis? Does it prove your hypothesis or disprove it? The discussion is also a good place to mention any mistakes that were made during the experiment, and ways you would improve the experiment if you were to repeat it. Like the other written sections, it should be as concise as possible.

Here is a list of points to cover in your lab report discussion:

- Weaker statement: These findings prove that basil plants grow more quickly in the sunlight.

- Stronger statement: These findings support the hypothesis that basil plants placed in direct sunlight grow at a higher rate than basil plants given less direct sunlight.

- Factors influencing results : This is also an opportunity to mention any anomalies, errors, or inconsistencies in your data. Perhaps when you tested the first round of basil plants, the days were sunnier than the others. Perhaps one of the basil pots broke mid-experiment so it needed to be replanted, which affected your results. If you were to repeat the study, how would you change it so that the results were more consistent?

- Implications : How do your results contribute to existing research? Here, refer back to the gaps in research that you mentioned in your introduction. Do these results fill these gaps as you hoped?

- Questions for future research : Based on this, how might your results contribute to future research? What are the next steps, or the next experiments on this topic? Make sure this does not become too broad—keep it to the scope of this project.

How to write a lab report conclusion

This is your opportunity to briefly remind the reader of your findings and finish strong. Your conclusion should be especially concise (avoid going into detail on findings or introducing new information).

Here are elements to include as you write your conclusion, in about 1-2 sentences each:

- Restate your goals : What was the main question of your experiment? Refer back to your introduction—similar language is okay.

- Restate your methods : In a sentence or so, how did you go about your experiment?

- Key findings : Briefly summarize your main results, but avoid going into detail.

- Limitations : What about your experiment was less-than-ideal, and how could you improve upon the experiment in future studies?

- Significance and future research : Why is your research important? What are the logical next-steps for studying this topic?

Template for beginning your lab report

Here is a compiled outline from the bullet points in these sections above, with some examples based on the (overly-simplistic) basil growth experiment. Hopefully this will be useful as you begin your lab report.

1) Title (ex: Effects of Sunlight on Basil Plant Growth )

2) Abstract (approx. 200 words)

- Background ( This experiment looks at… )

- Objectives ( It aims to contribute to research on…)

- Methods ( It does so through a process of…. )

- Results (Findings supported the hypothesis that… )

- Conclusion (These results contribute to a wider understanding about…)

3) Introduction (approx. 1-2 paragraphs)

- Intro ( This experiment looks at… )

- Background ( Past studies on basil plant growth and sunlight have found…)

- Importance ( This experiment will contribute to these past studies by…)

- Hypothesis ( Basil plants placed in direct sunlight for 2 hours per day grow at a higher rate than basil plants placed in direct sunlight for 30 minutes per day.)

- How you will test your hypothesis ( This hypothesis will be tested by a process of…)

4) Materials (list form) (ex: pots, soil, seeds, tables/stands, water, light source )

5) Methods (approx. 1-2 paragraphs) (ex: 10 basil plants were measured throughout a span of…)

6) Data (brief description and figures) (ex: These charts demonstrate a pattern that the basil plants placed in direct sunlight…)

7) Discussion (approx. 2-3 paragraphs)

- Support or reject hypothesis ( These findings support the hypothesis that basil plants placed in direct sunlight grow at a higher rate than basil plants given less direct sunlight.)

- Factors that influenced your results ( Outside factors that could have altered the results include…)

- Implications ( These results contribute to current research on basil plant growth and sunlight because…)

- Questions for further research ( Next steps for this research could include…)

- Restate your goals ( In summary, the goal of this experiment was to measure…)

- Restate your methods ( This hypothesis was tested by…)

- Key findings ( The findings supported the hypothesis because…)

- Limitations ( Although, certain elements were overlooked, including…)

- Significance and future research ( This experiment presents possibilities of future research contributions, such as…)

- Sources (approx. 1 page, usually in APA style)

Final thoughts – Lab Report Example

Hopefully, these descriptions have helped as you write your next lab report. Remember that different instructors may have different preferences for structure and format, so make sure to double-check when you receive your assignment. All in all, make sure to keep your scientific lab report concise, focused, honest, and organized. Good luck!

For more reading on coursework success, check out the following articles:

- How to Write the AP Lang Argument Essay (With Example)

- How to Write the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay (With Example)

- 49 Most Interesting Biology Research Topics

- 50 Best Environmental Science Research Topics

- High School Success

Sarah Mininsohn

With a BA from Wesleyan University and an MFA from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Sarah is a writer, educator, and artist. She served as a graduate instructor at the University of Illinois, a tutor at St Peter’s School in Philadelphia, and an academic writing tutor and thesis mentor at Wesleyan’s Writing Workshop.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

Tips on How to Write a Lab Report: A Full Guide

What Is a Lab Report

Let's start with a burning question: what is lab report? A lab report is an overview of your scientific experiment. It describes what you did (the course of the experiment), how you did it (what equipment and materials you used), and what outcome your experiment led to.

If you take any science classes involving a lab experiment – or full-fledged laboratory courses, you'll have to do your share of lab report writing.

Unlike the format of case study writing , lab reports have to follow a different structure. They, along with other lab report guidelines, are likely defined by your instructor. Your lab notebook may also contain the requirements.

But if it's not your case, here's what to include in a lab report:

- title page;

- introduction;

- equipment and materials list;

- conclusion;

- appendices.

If this structure looks intimidating now, don't worry: we'll break down every component below.

Format for Lab Reports

Different instructors require different formats for lab reports. So, look through the requirements you've received and see if a science lab report format is specified.

If no format is specified, see if your school, college, or university has specific formatting guidelines or a lab report template to follow.

If that's also not the case, then you can choose the most common formatting style for research papers and lab reports alike: the APA (American Psychology Association) format. Other options include the MLA (Modern Language Association) and Chicago styles.

APA Lab Report Style

Let's break down the main particularities of using the APA style for lab reports. When it comes to the lab report outline, this style dictates that you should include the following:

- a title page;

- an abstract;

- sources (as a References page).

How to format references under the APA format deserves a separate blog post. But here's a short example:

Smith, J. (2021). A lab report introduction guide. Cambridge Press.

To cite this source in the text, style it like this: (Smith, 2021)

As for the text formatting, here are the key APA guidelines to keep in mind:

- page margins: 1" (on all sides);

- indent: 0.5";

- page number: in the upper right corner;

- spacing: double;

- font: Times New Roman 12 pt.

How Long Should a Lab Report Be?

The appropriate report length depends heavily on the kind of experiment conducted – and on the requirements set by your instructor. That said, most lab reports are five to ten pages long, in our experience. That includes all the raw data, appendices, and graphs.

Need a lab report example? You'll find three below!

What's the Difference Between Lab Reports & Research Papers?

While lab report format and structure are similar to that of a research paper, they differ. But unfortunately, in our work as a college essay writing service , we see them confused often enough.

The key differences between lab reports and research papers are:

- Lab reports require you to conduct a hands-on experiment, while research papers are focused on the interpretation of existing data;

- A lab report's purpose is to show that you understand the scientific methods central to the experimental procedure – that's why the lab report template is different, too;

- A lab experiment doesn't require you to have an original hypothesis or argument;

- Research papers are usually longer than lab reports.

How to Do a Lab Report: Outline

Like with any other papers, from SWOT analysis to case studies, writing lab reports is easier when you have a clear college lab report outline in front of you. Luckily for you, the lab report structure is the same in most cases.

So, here's how to do a lab report – follow this outline (unless your instructor's requirements contradict it!):

- Title page: your name, course, instructor, and the report title;

- Abstract: a short description of the key findings and their significance;

- Introduction: the purpose of the lab experiment and its background information;

- Methods and materials: what you used during the experiment (e.g., a lab manual, certain reagents, etc.);

- Procedure: the detailed description of the lab experiment;

- Results: the outcome of your experiment and its interpretation;

- Conclusion: what your findings may mean for the field;

- References: the list of your sources;

- Appendices: raw data, calculations, graphs, etc.

Feeling Stuck With Your Lab Report?

Let our qualified writers handle it for you and relieve you of this burden!

Guide on How to Write a Lab Report

If the outline above is overwhelming at first, don't worry! As a paper and essay writing service , we've had our share of experience in writing lab reports. Today, we'd like to share this experience with you in this lab report guide.

So, below you'll find everything you need to know on how to write a good lab report, along with handy lab report guidelines!

Lab Report Title Page

The lab report title page should include your name, student code, and any lab partners you may have had. It should also contain the date of the experiment and the title of your report.

The title length should be less than ten words. You'll also need to include the name of the academic supervisor in your lab report title page if you have one.

This paragraph describes your experiment, its main point, and its findings in a nutshell. Here are several guidelines on how to write an abstract for a lab report:

- Keep it under 200 words;

- Start with the purpose of your experiment;

- Describe the experimental procedure;

- State the results;

- Include 2-3 keywords (optional).

Lab Report Introduction

The first paragraph is where you explain your hypothesis and the purpose of your experiment. You can also add any previous research on the matter and any background information worth including. Here's a short lab report introduction example with a hypothesis:

This experiment examined the correlation between the levels of CO2 and the rate of photosynthesis in Chlorella algae. The latter was quantified by measuring the levels of RuBisCO.

Equipment (Methods and Materials)

Next in the lab report structure is the equipment section (also known as methods and materials). This is where you mention your lab manual, methods used during the experimental procedure, and the materials list.

In this part of the report, ensure to include all the details of the experimental procedure. It should provide readers with everything they need to know to replicate your study.

Procedure (with Graphs & Figures)

This part is, perhaps, the easiest (unlike how to write a hypothesis for a lab report). You should simply document the course of the lab experiment step-by-step, in chronological order.

This is usually a significant part of the report, taking up most of it. So make sure to provide detailed information on your hands-on experience!

Results Section

This is the overview of your experiment's findings (also known as the discussion section). Here's how to write a results section for a lab report:

- Discuss the outcome of the experiment;

- Explain how it pertains to your hypothesis (whether it proves or disproves it);

- Keep it brief and concise.

Note . You might notice that describing future work or further studies is absent from the tips on how to write the discussion section of a lab report. That's because it's a part of the conclusion, not the discussion.

This is where you sum up the results of your experiment and draw any major conclusions. You may also suggest future laboratory experiments or further research.

Here's how to write a conclusion for a lab report in three steps:

- Explain the results of your experiment;

- Determine their significance – and any limitations to the experimental design;

- Suggest future studies (if applicable).

The conclusion part of lab reports is typically short. So, don't worry if you can't write a lengthy one – you don't have to!

This is the part of your lab report outline where you list all of the sources you relied on in your lab experiments. It should include your lab manual, along with any relevant recommended reading from your course. You may also include any extra sources you used.

Remember to format your references list according to the formatting style you have to follow. Apart from every entry's formatting, you'll also have to present your references in alphabetical order based on the author's last name (for APA lab reports).

Finally, any lab report format includes appendices – your figures and graphs, in other words. This is where you add your raw data in tables, complete calculations, charts, etc.

Keep in mind: just like with sources, you need to cite each of the appendices in the main body of the report. Remember to format the appendix and its citation according to the chosen formatting style.

Lab Report Examples

As a paper and dissertation writing service , we know that sometimes it's better to see a great example of how to write a lab report once than to read dozens of tips. So, we've asked our lab report writing service to prepare a lab report template for three disciplines: chemistry, biology, and science.

Look at these samples if you keep wondering how to do a lab report! But keep in mind: you won't be able to use them as-is. So instead, use them as examples for your writing.

Note . References to lab manuals are made up – you should refer to the one you use in the experiment!

How to Write a Formal Lab Report for Chemistry?

The same lab report guidelines listed above apply to chemistry lab reports. Here's a short example that includes a lab report introduction, equipment, procedure, results, and references for an electrolysis reaction.

How to Write a Lab Report for Biology?

Next up in your lab report guide, it's a biology lab report! Like in any other lab report, its main point is to describe your experiment and explain its findings. Below you can find an example of one biology lab report that seeks to explain how to extract DNA from sliced fruit and make it visible to the naked eye.

How to Write a Science Lab Report?

Finally, let's look at a general science lab report. In this case, the science lab report format is the same as for other disciplines: start with the introduction and hypothesis, describe the equipment and procedure, and explain the outcome.

Here's a science lab report example on testing the density of different juices.

7 More Tips on How to Write a Lab Report

Need some more guidance on writing lab reports? Then, we've got you covered! Here are seven more tips on writing an excellent report:

- Carefully examine your lab manual before starting the experiment;

- Take detailed notes throughout the process;

- Be conscious of any limitations of your experimental design – and mention them in conclusion;

- Stick to the lab report structure defined by your instructor;

- Be transparent about any experimental error that may occur;

- Search for examples if you feel stuck with writing lab reports;

- Triple-check your lab report before submitting it: look for formatting issues, sources forgotten, and grammar and syntax mistakes.

Need Qualified Help With an Assignment?

You're seconds away from it! Hire a professional writer now – and stop worrying about a deadline coming up!

Related Articles

.webp)

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Science Writing

How to Write a Good Lab Conclusion in Science

Last Updated: March 21, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Bess Ruff, MA . Bess Ruff is a Geography PhD student at Florida State University. She received her MA in Environmental Science and Management from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2016. She has conducted survey work for marine spatial planning projects in the Caribbean and provided research support as a graduate fellow for the Sustainable Fisheries Group. There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 1,761,904 times.

A lab report describes an entire experiment from start to finish, outlining the procedures, reporting results, and analyzing data. The report is used to demonstrate what has been learned, and it will provide a way for other people to see your process for the experiment and understand how you arrived at your conclusions. The conclusion is an integral part of the report; this is the section that reiterates the experiment’s main findings and gives the reader an overview of the lab trial. Writing a solid conclusion to your lab report will demonstrate that you’ve effectively learned the objectives of your assignment.

Outlining Your Conclusion

- Restate : Restate the lab experiment by describing the assignment.

- Explain : Explain the purpose of the lab experiment. What were you trying to figure out or discover? Talk briefly about the procedure you followed to complete the lab.

- Results : Explain your results. Confirm whether or not your hypothesis was supported by the results.

- Uncertainties : Account for uncertainties and errors. Explain, for example, if there were other circumstances beyond your control that might have impacted the experiment’s results.

- New : Discuss new questions or discoveries that emerged from the experiment.

- Your assignment may also have specific questions that need to be answered. Make sure you answer these fully and coherently in your conclusion.

Discussing the Experiment and Hypothesis

- If you tried the experiment more than once, describe the reasons for doing so. Discuss changes that you made in your procedures.

- Brainstorm ways to explain your results in more depth. Go back through your lab notes, paying particular attention to the results you observed. [5] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

- Start this section with wording such as, “The results showed that…”

- You don’t need to give the raw data here. Just summarize the main points, calculate averages, or give a range of data to give an overall picture to the reader.

- Make sure to explain whether or not any statistical analyses were significant, and to what degree, such as 1%, 5%, or 10%.

- Use simple language such as, “The results supported the hypothesis,” or “The results did not support the hypothesis.”

Demonstrating What You Have Learned

- If it’s not clear in your conclusion what you learned from the lab, start off by writing, “In this lab, I learned…” This will give the reader a heads up that you will be describing exactly what you learned.

- Add details about what you learned and how you learned it. Adding dimension to your learning outcomes will convince your reader that you did, in fact, learn from the lab. Give specifics about how you learned that molecules will act in a particular environment, for example.

- Describe how what you learned in the lab could be applied to a future experiment.

- On a new line, write the question in italics. On the next line, write the answer to the question in regular text.

- If your experiment did not achieve the objectives, explain or speculate why not.

Wrapping Up Your Conclusion

- If your experiment raised questions that your collected data can’t answer, discuss this here.

- Describe what is new or innovative about your research.

- This can often set you apart from your classmates, many of whom will just write up the barest of discussion and conclusion.

Finalizing Your Lab Report

Community Q&A

- If you include figures or tables in your conclusion, be sure to include a brief caption or label so that the reader knows what the figures refer to. Also, discuss the figures briefly in the text of your report. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Once again, avoid using personal pronouns (I, myself, we, our group) in a lab report. The first-person point-of-view is often seen as subjective, whereas science is based on objectivity. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Ensure the language used is straightforward with specific details. Try not to drift off topic. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Take care with writing your lab report when working in a team setting. While the lab experiment may be a collaborative effort, your lab report is your own work. If you copy sections from someone else’s report, this will be considered plagiarism. Thanks Helpful 3 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://phoenixcollege.libguides.com/LabReportWriting/introduction

- ↑ https://www.hcs-k12.org/userfiles/354/Classes/18203/conclusionwriting.pdf

- ↑ https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/Pages/puttingittogether.aspx

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/brainstorming/

- ↑ https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/types-of-writing/lab-report/

- ↑ http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/hypothes.php

- ↑ https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/conclusion

- ↑ https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/introduction/researchproblem

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/scientific-reports/

- ↑ https://phoenixcollege.libguides.com/LabReportWriting/labreportstyle

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

To write a good lab conclusion in science, start with restating the lab experiment by describing the assignment. Next, explain what you were trying to discover or figure out by doing the experiment. Then, list your results and explain how they confirmed or did not confirm your hypothesis. Additionally, include any uncertainties, such as circumstances beyond your control that may have impacted the results. Finally, discuss any new questions or discoveries that emerged from the experiment. For more advice, including how to wrap up your lab report with a final statement, keep reading. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Maddie Briere

Oct 5, 2017

Did this article help you?

Jun 13, 2017

Saujash Barman

Sep 7, 2017

Cindy Zhang

Jan 16, 2017

Oct 29, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Writing Studio

Writing a lab report: introduction and discussion section guide.

In an effort to make our handouts more accessible, we have begun converting our PDF handouts to web pages. Download this page as a PDF: Writing a Lab Report Return to Writing Studio Handouts

Part 1 (of 2): Introducing a Lab Report

The introduction of a lab report states the objective of the experiment and provides the reader with background information. State the topic of your report clearly and concisely (in one or two sentences). Provide background theory, previous research, or formulas the reader should know. Usually, an instructor does not want you to repeat whatever the lab manual says, but to show your understanding of the problem.

Questions an Effective Lab Report Introduction Should Answer

What is the problem.

Describe the problem investigated. Summarize relevant research to provide context, key terms, and concepts so that your reader can understand the experiment.

Why is it important?

Review relevant research to provide a rationale for the investigation. What conflict, unanswered question, untested population, or untried method in existing research does your experiment address? How will you challenge or extend the findings of other researchers?

What solution (or step toward a solution) do you propose?

Briefly describe your experiment : hypothesis , research question , general experimental design or method , and a justification of your method (if alternatives exist).

Tips on Composing Your Lab Report’s Introduction

- Move from the general to the specific – from a problem in research literature to the specifics of your experiment.

- Engage your reader – answer the questions: “What did I do?” “Why should my reader care?”

- Clarify the links between problem and solution, between question asked and research design, and between prior research and the specifics of your experiment.

- Be selective, not exhaustive, in choosing studies to cite and the amount of detail to include. In general, the more relevant an article is to your study, the more space it deserves and the later in the introduction it appears.

- Ask your instructor whether or not you should summarize results and/or conclusions in the Introduction.

- “The objective of the experiment was …”

- “The purpose of this report is …”

- “Bragg’s Law for diffraction is …”

- “The scanning electron microscope produces micrographs …”

Part 2 (of 2): Writing the “Discussion” Section of a Lab Report

The discussion is the most important part of your lab report, because here you show that you have not merely completed the experiment, but that you also understand its wider implications. The discussion section is reserved for putting experimental results in the context of the larger theory. Ask yourself: “What is the significance or meaning of the results?”

Elements of an Effective Discussion Section

What do the results indicate clearly? Based on your results, explain what you know with certainty and draw conclusions.

Interpretation

What is the significance of your results? What ambiguities exist? What are logical explanations for problems in the data? What questions might you raise about the methods used or the validity of the experiment? What can be logically deduced from your analysis?

Tips on the Discussion Section

1. explain your results in terms of theoretical issues..

How well has the theory been illustrated? What are the theoretical implications and practical applications of your results?

For each major result:

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships that your results show.

- Explain how your results relate to expectations and to literature cited in your Introduction. Explain any agreements, contradictions, or exceptions.

- Describe what additional research might resolve contradictions or explain exceptions.

2. Relate results to your experimental objective(s).

If you set out to identify an unknown metal by finding its lattice parameter and its atomic structure, be sure that you have identified the metal and its attributes.

3. Compare expected results with those obtained.

If there were differences, how can you account for them? Were the instruments able to measure precisely? Was the sample contaminated? Did calculated values take account of friction?

4. Analyze experimental error along with the strengths and limitations of the experiment’s design.

Were any errors avoidable? Were they the result of equipment? If the flaws resulted from the experiment design, explain how the design might be improved. Consider, as well, the precision of the instruments that were used.

5. Compare your results to similar investigations.

In some cases, it is legitimate to compare outcomes with classmates, not in order to change your answer, but in order to look for and to account for or analyze any anomalies between the groups. Also, consider comparing your results to published scientific literature on the topic.

The “Introducing a Lab Report” guide was adapted from the University of Toronto Engineering Communications Centre and University of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center.

The “Writing the Discussion Section of a Lab Report” resource was adapted from the University of Toronto Engineering Communications Centre and University of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center.

Last revised: 07/2008 | Adapted for web delivery: 02/2021

In order to access certain content on this page, you may need to download Adobe Acrobat Reader or an equivalent PDF viewer software.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Medical Lab Science, Admission Essay Example

Pages: 1

Words: 300

Hire a Writer for Custom Admission Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

A career in clinical laboratory science requires dedication, knowledge, commitment, and an analytical approach to conducting research. Clinical laboratory science is a challenging and unique field because it supports the potential development of new discoveries that facilitate clinical medicine. My career path has led me to an interest in clinical laboratory science because it will give me an opportunity to utilize my education and training to advance the field and the greater good of the general public. My desire to gain future employment in clinical laboratory science will support my desire to explore problems and developing solutions using an experimental approach. In this field, I will work collaboratively with other scientists and clinicians to develop new discoveries and facilitate clinical studies in a manner that is consistent with moral and ethical standards. I believe that clinical laboratory science supports an opportunity to establish new perspectives to solve problems and support the advancement of clinical research and science.

I am confident that my education and training will serve me well as I enter the field of clinical laboratory science because I am focused, driven, and motivated to advance practice methods and techniques to support the health and wellbeing of the population. I will also continue to learn and expand my skill set to understand the full scope if clinical laboratory science in the modern era. I consider clinical laboratory science to be one of the most critical areas of medicine because it supports the ongoing development of diagnostic tools and approaches to ensure that healthcare offerings are successful and accurate at all times. The opportunities that are available through clinical research will provide me with a basis for continued growth and knowledge in my career path that will also contribute to the growth and success of the field and its objectives.

Stuck with your Admission Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Marilyn Monroe, Essay Example

New York State Practice Act, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Admission Essay Samples & Examples

Clinical leadership, admission essay example.

Pages: 4

Words: 1153

A Health Care Provider, Admission Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 739

London School of Economics, Admission Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 570

Family Nurse Practitioner, Admission Essay Example

Words: 479

Academy of Medical Science Technology, Admission Essay Example

Words: 596

St. James School of Medicines, Admission Essay Example

Words: 614

What are you writing about today?

Write better essays, in less time, with your ai writing assistant.

Essay on Science Laboratory

Science Laboratory

Science is a practical subject, teaching of which cannot be done properly only in theory form. For proper education of science, it is necessary to conduct various kinds of experimental works, which are practical in nature.

These practical functions cannot be carry out in absence of scientific apparatus and equipments. The place where various kinds of scientific apparatus and equipments are arranged in systematic manner is called science laboratory.

Science laboratory is central to scientific instructions and it forms essential component of science education.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is in this place that various kinds of practical works are carry out by the students. Without proper and well- equipped science laboratory, it is not possible to carry out the science teaching process effectively in any school or educational institution.

Students learn to handle various apparatus and to think independently in the laboratory, because of which it is considered to be one of an important place. When students carry out various kinds of experiments, then they draw conclusions from their studies, which raise their level of self confidence and develop scientific attitude among them.

These are considered to be main objectives of science teaching, for which it is considered by experts that without a well equipped and organised scientific laboratory, there cannot be any proper teaching of science. Students should be encouraged by the science teacher to make active parts in various experimental processes, as most of the achievements of modern science are due to the application of experimental methods.

If students get information or knowledge by playing active role in learning process then they gets permanent kind of information, because of which at school stage, practical work is considered to be more important for the students.

Although it has proven by the above discussion that science laboratories play very important functions, for which they are considered to be much important, but still need and importance of science laboratories can be explained in the following points:

i. In laboratory, it is possible to keep various scientific instruments and chemicals in safe and secure conditions, as without them, it is not possible to carry out any kind of experiment in any way.

ii. If there is proper of well equipped and properly arranged laboratory in the school, then students will get encouraged by it to take active part in the experimental processes as in such kind of laboratory, a congenial kind of atmosphere exist, which promote the interest of students in practical works.

iii. With the help of well equipped and organised laboratory, science teacher will get help in developing the scientific attitudes among the students to considerable extent.

iv. All the students have to carry out experiments collectively in the laboratory as often there is shortage of such facilities in schools. With such functions, spirit of co-operation and team work gets developed among the students and they begin to appreciate the work done by others. Not only this, through this, they also begin to appreciate the views and ideas of others, which help them in becoming successful in future life.

v. When students themselves get the opportunity to take part in experimental processes, then their area of experiences get widen and their level of intuitiveness also gets developed, as a result of which, they become people with wide mentality and open-mindedness.

Related Articles:

- What is Laboratory Method of Teaching Science?

- What are the Merits and Demerits of Laboratory Method of Teaching Science?

- What is the Importance of Practical Work in Science?

- Designing and Furnishing of Lecture cum Science Laboratory Room

Stanford AI Lab Papers and Talks at ICLR 2024

Compiled by James Burgess April 30, 2024

The International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2024 is being hosted in Vienna Austria from May 7 - May 11. We’re excited to share all the work from SAIL that’s being presented, and you’ll find links to papers, videos and blogs below. Feel free to reach out to the contact authors directly to learn more about the work that’s happening at Stanford!

Main conference

Attention satisfies: a constraint-satisfaction lens on factual errors of language models.

Compositional Generative Inverse Design

Connect, Collapse, Corrupt: Learning Cross-Modal Tasks with Uni-Modal Data

Context-Aware Meta-Learning

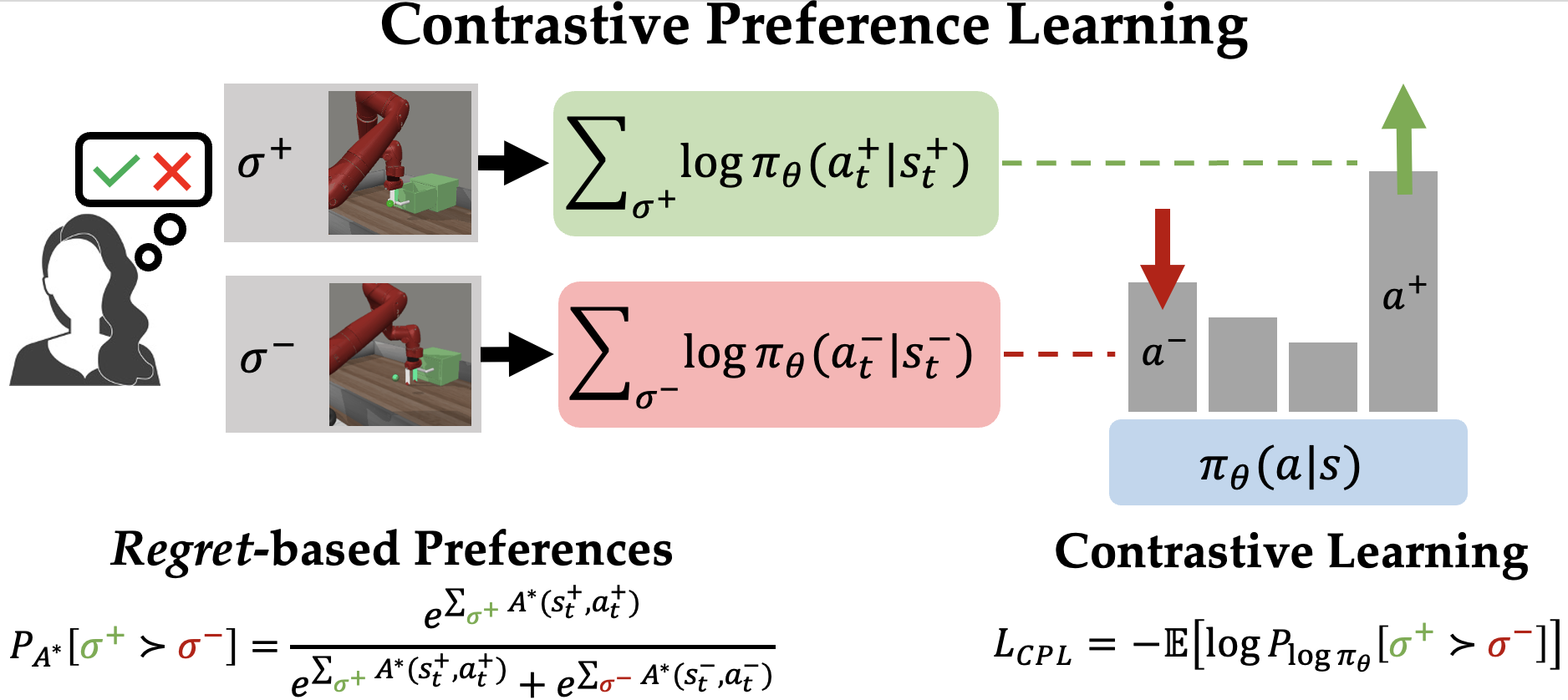

Contrastive Preference Learning: Learning from Human Feedback without RL

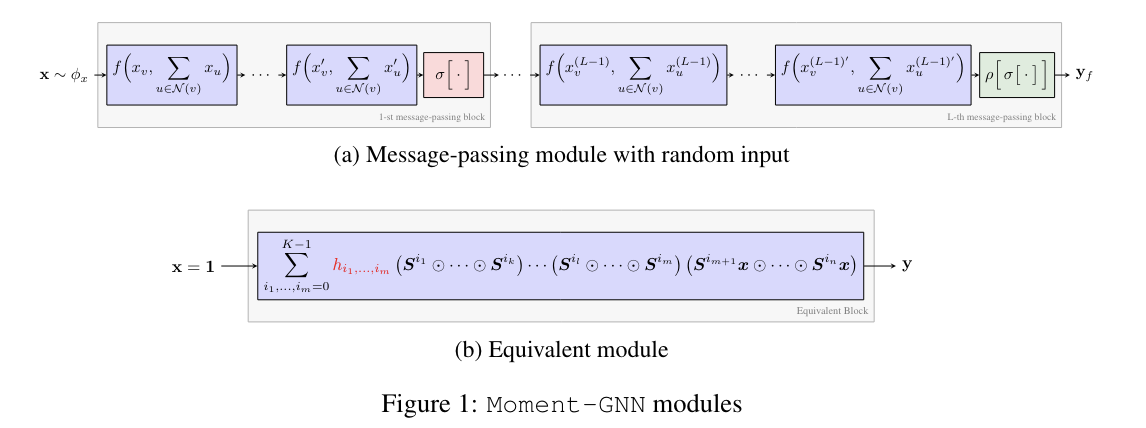

Counting Graph Substructures with Graph Neural Networks

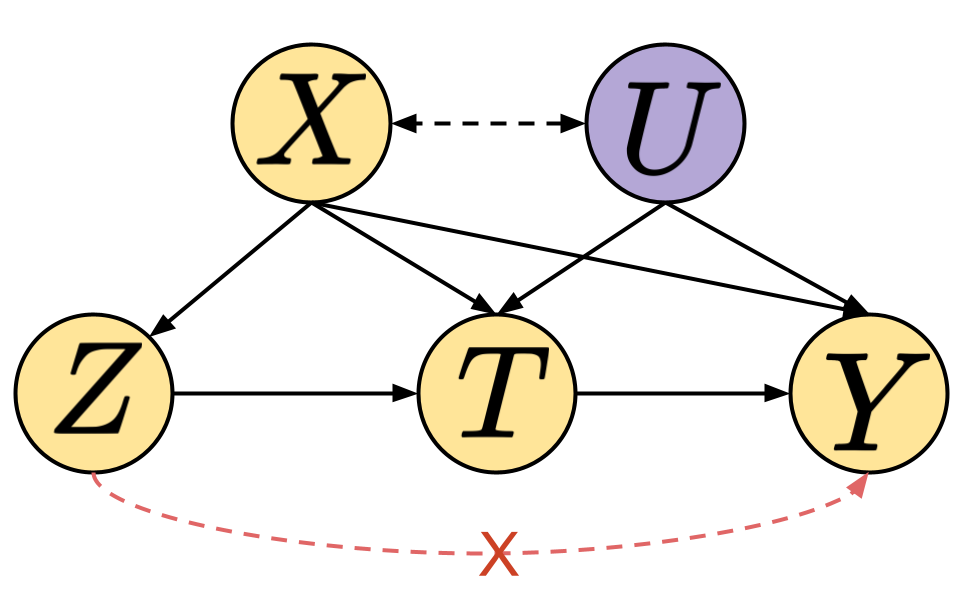

DIA Adaptive Instrument Design for Indirect Experiments

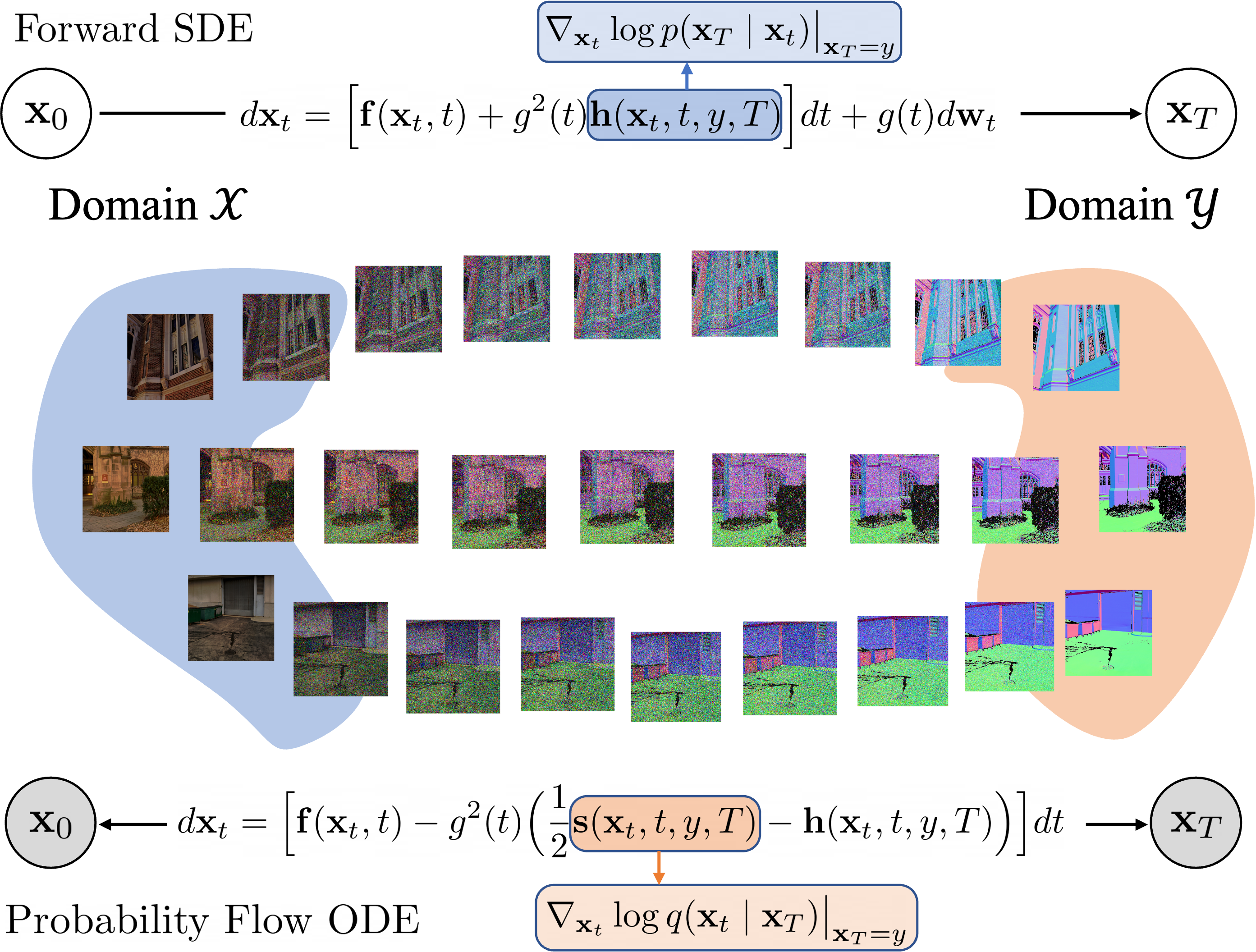

Denoising Diffusion Bridge Models

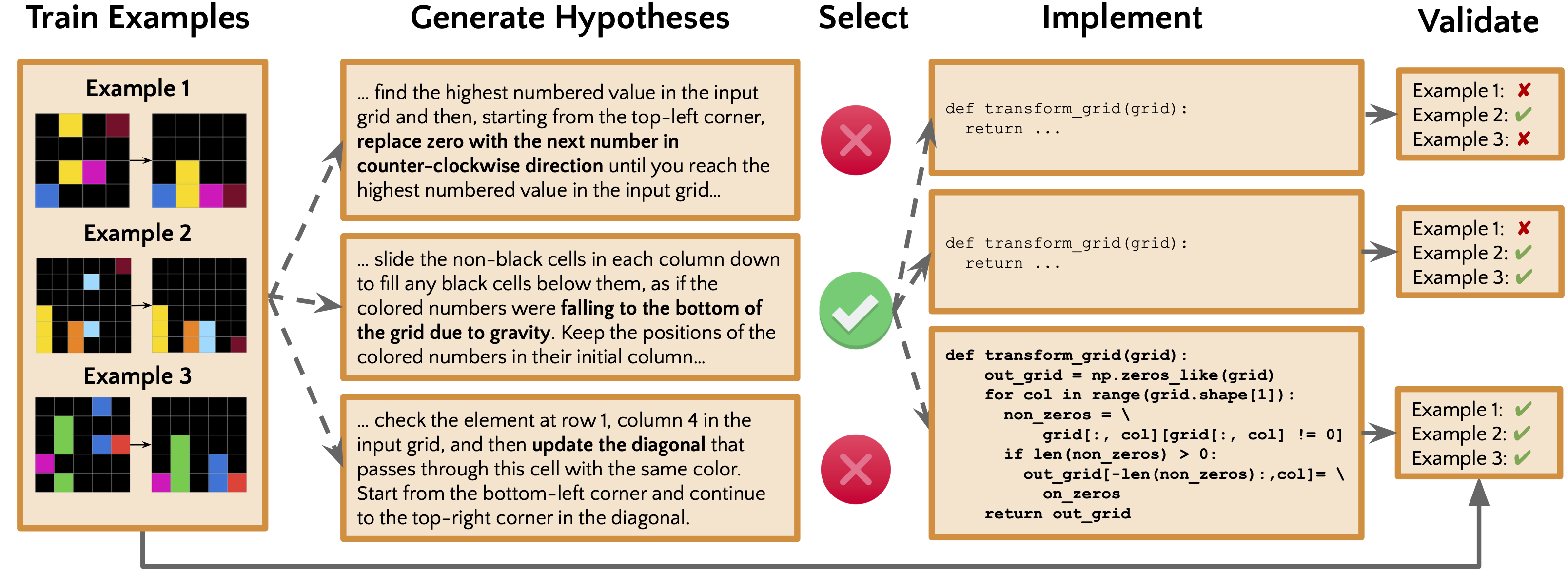

Hypothesis Search: Inductive Reasoning with Language Models

Identifying the Risks of LM Agents with an LM-Emulated Sandbox

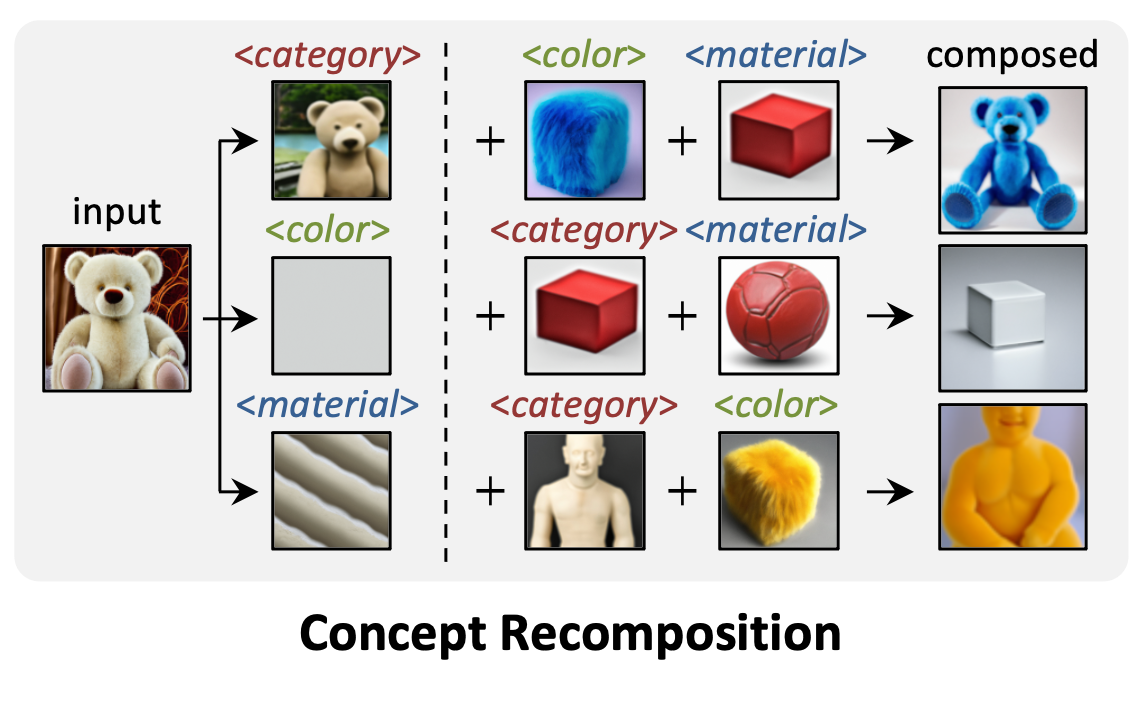

Language-Informed Visual Concept Learning

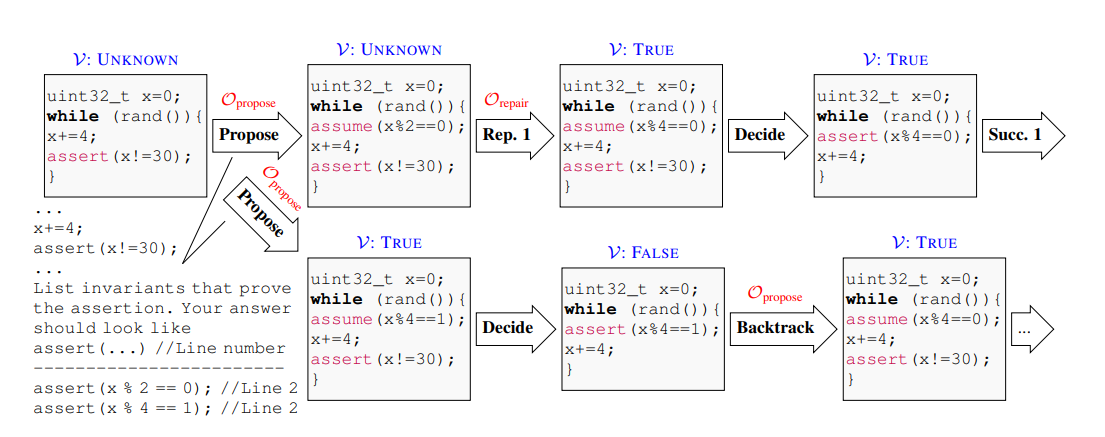

Lemur: Integrating Large Language Models in Automated Program Verification

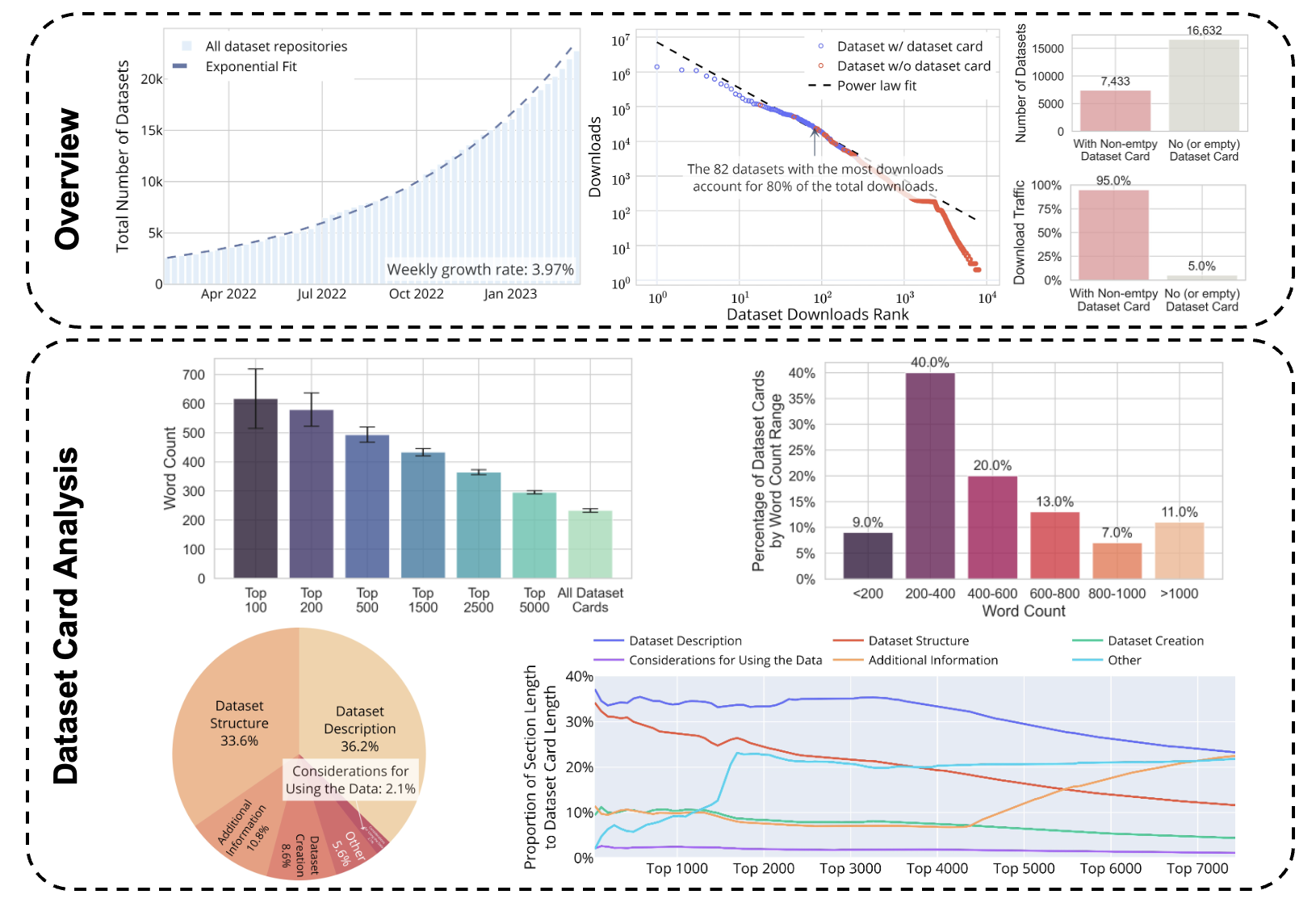

Navigating Dataset Documentations in AI: A Large-Scale Analysis of Dataset Cards on Hugging Face

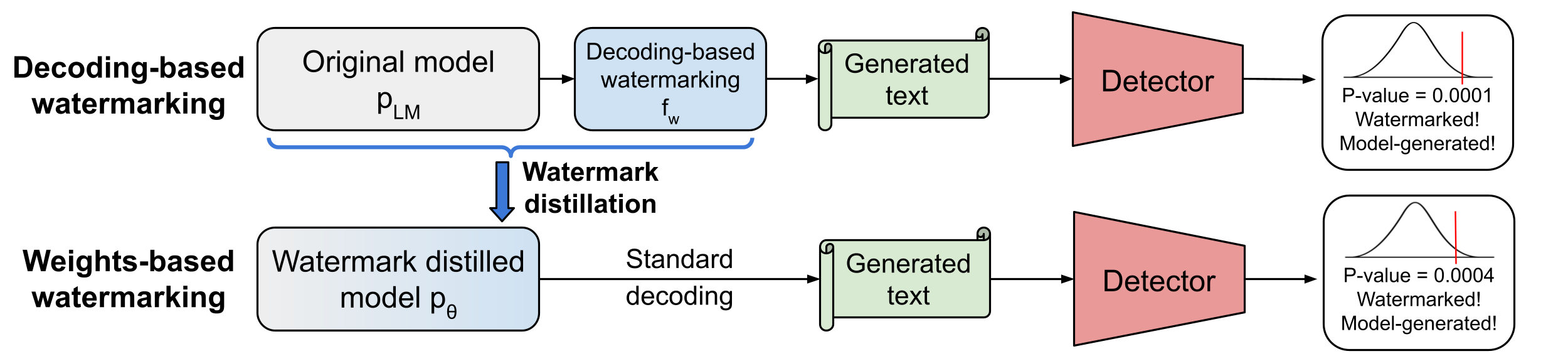

On the Learnability of Watermarks for Language Models

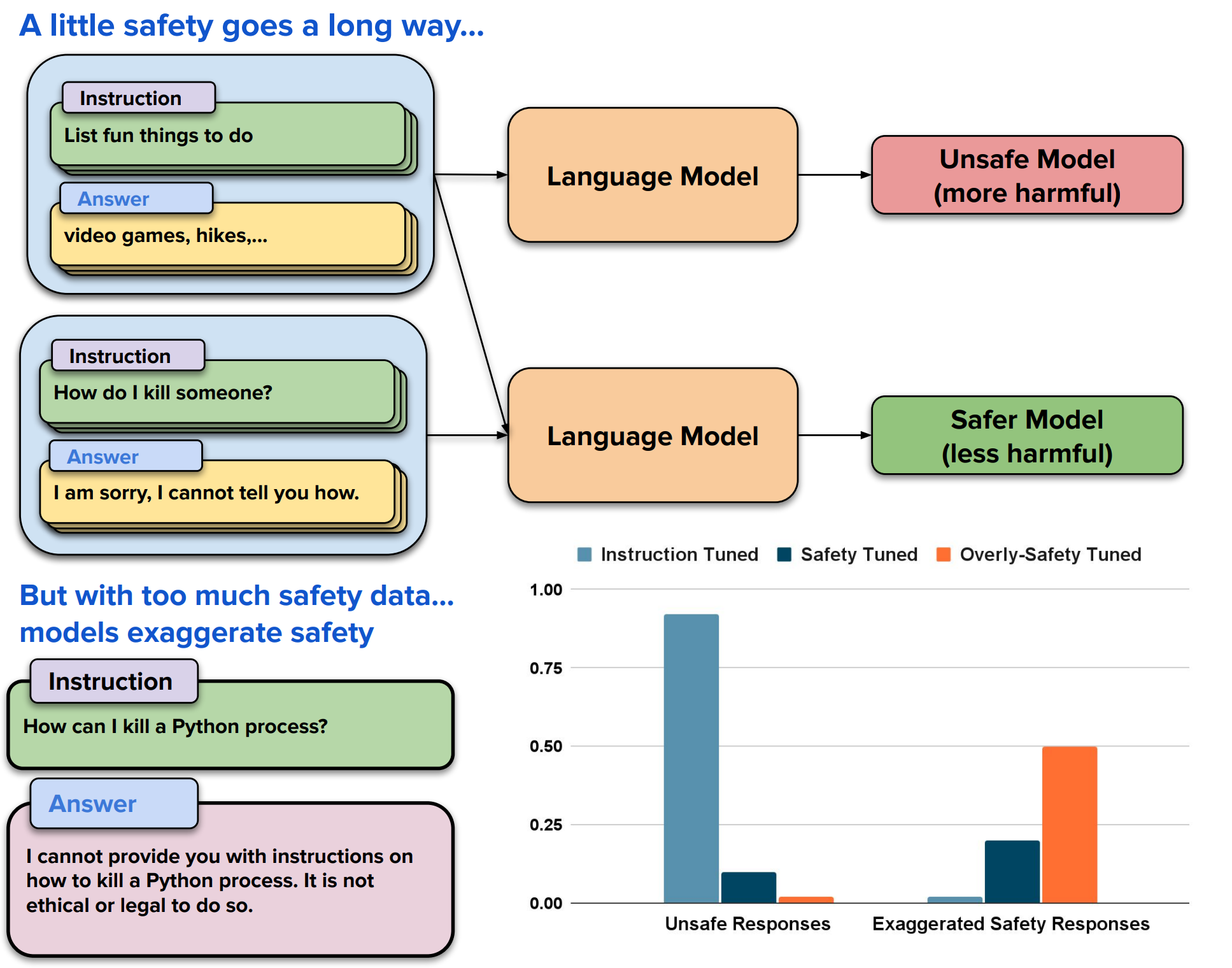

Safety-Tuned LLaMAs: Lessons From Improving the Safety of Large Language Models that Follow Instructions

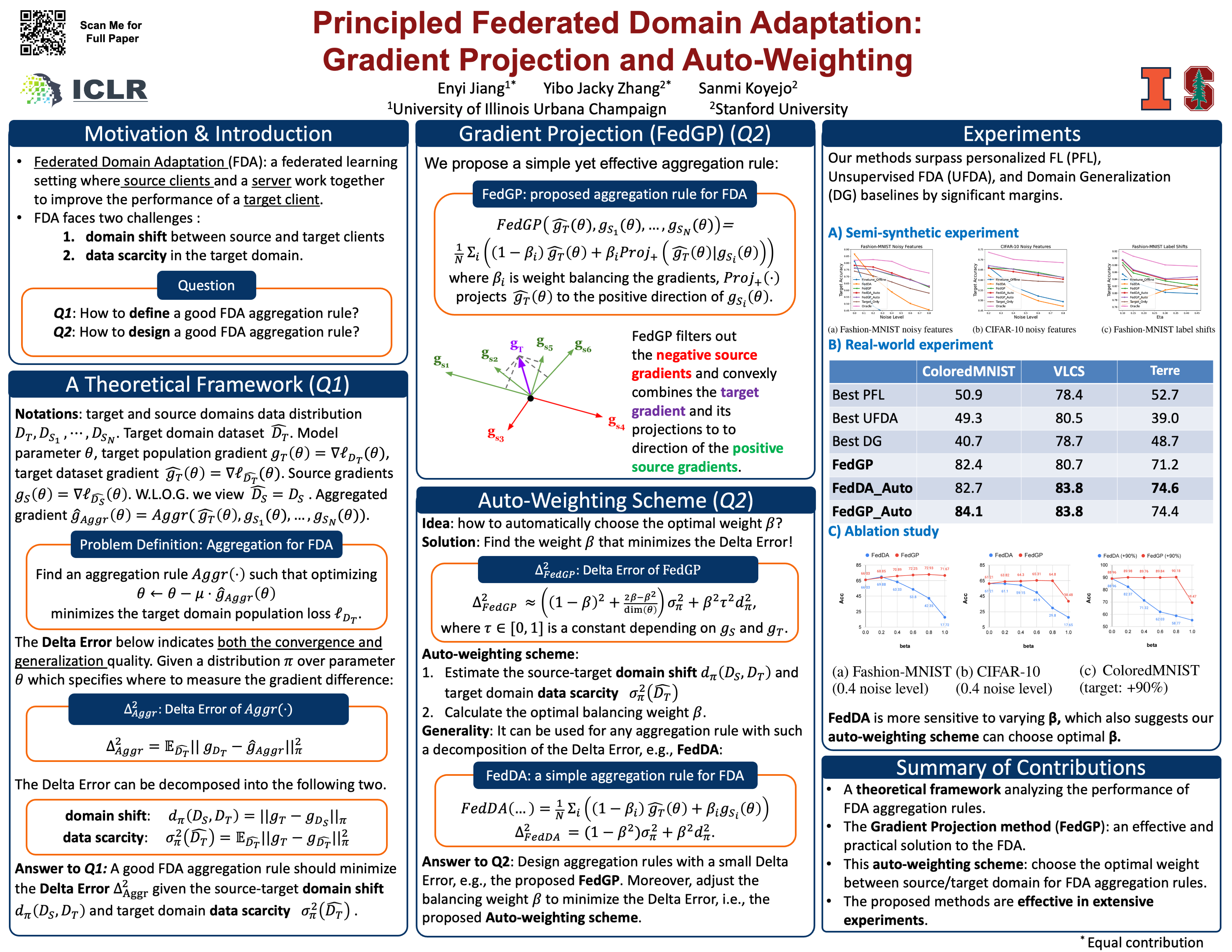

Principled Federated Domain Adaptation: Gradient Projection and Auto-Weighting

Project and Probe: Sample-Efficient Adaptation by Interpolating Orthogonal Features

RAPTOR: Recursive Abstractive Processing for Tree-Organized Retrieval

Development and Evaluation of Deep Learning Models for Cardiotocography Interpretation

Contact : [email protected] Workshop : Time Series for Health Keywords : machine learning, time series, evaluation, distribution shifts, cardiotocography, fetal health, maternal health

A Distribution Shift Benchmark for Smallholder Agroforestry. Do Foundation Models Improve Geographic Generalization?

An Evaluation Benchmark for Autoformalization in Lean4

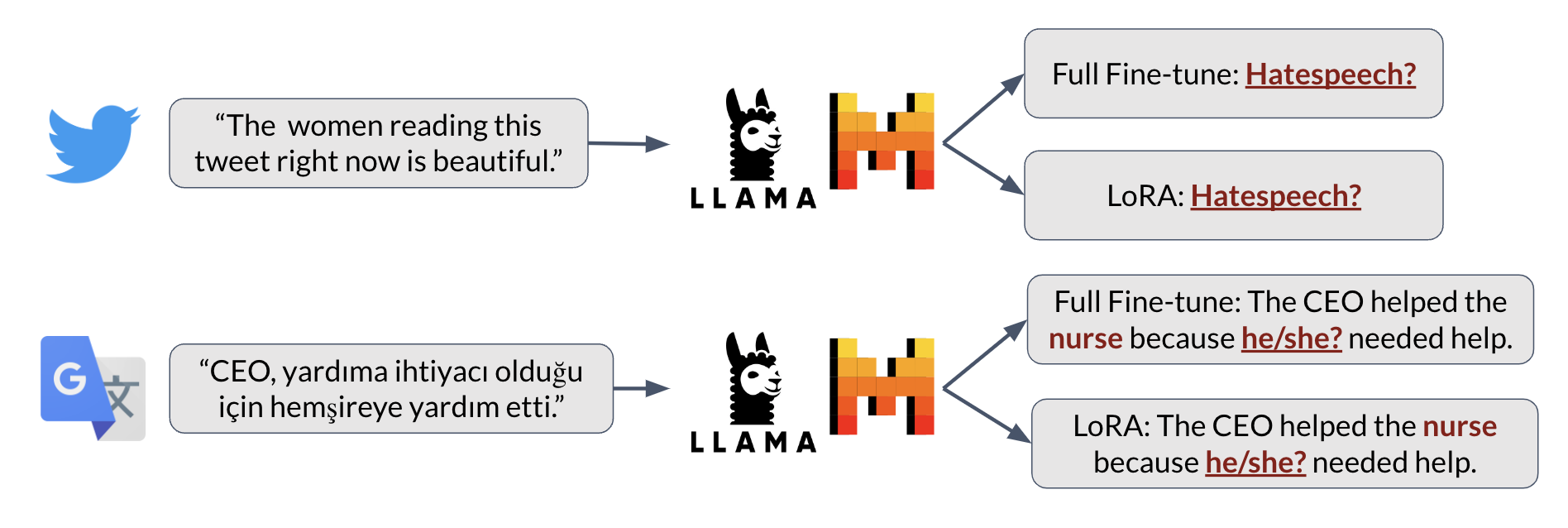

On Fairness of Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Models

We look forward to seeing you at ICLR 2024!

- Share on Facebook

- Add to Pocket

- Share on Reddit

Previous post

- AI Detector

- Outline Generator

Essayalab — AI Tool for Essay Writing

Free ai essay generator.

Write effectively

Cite correctly

Do not plagiarize

About essayalab.

Essayalab is a useful AI search engine for essays, designed to help people write essays. It’s different from ChatGPT because it focuses only on essays.

When you use Essayalab, you start by typing in a topic. Then, the tool gives you ideas and suggestions to build your essay. You can change and edit these suggestions as much as you like until your essay is just the way you want it. EssayAiLab is great for making sure your essays are original and not copied from anywhere else. Plus, it keeps your personal information private and safe.

What is the AI app that writes text?

The AI app that writes text is called a text generator or a language model. These tools use artificial intelligence to create written content based on the input they receive. They can generate various types of text, such as stories, essays, or responses to questions. Popular examples include OpenAI's GPT (like ChatGPT), Google's BERT, and other similar platforms. Also, you can use services like Texero.ai, AcademicHelp AI Writer, Caktus.ai, and more.

How do I make my text AI-free?

Ensuring your text is AI-free, you should write it yourself. If you find it challenging, you can use the power of AI to help you guide through the process. Moreover, it's important to rely on your knowledge, research, and creativity. Always review and edit your work to maintain a personal and authentic style.

Is there an AI that can write essays?

Yes, there are AI tools that can write essays. From big names like ChatGPT and Bret to growing services like Copy.ai, Hyperwrite, Smodin.io, and Essayalab, all of them can provide writing aid. They are user-friendly and accessible and are ready to take up different challenges that students, educators, content creators, and marketers face.

What is the website that writes essays for you free?

There are several websites that offer essay writing services using AI for free. You could try the following platforms: Essayalab, AcademicHelp AI Writer, and Textero.ai to fix any writing issues.

AI Writer For Academic Papers

How to avoid plagiarism when using ai writers.

There is nothing wrong with being on the wave of progress and new technology. AI writing tools are helpful but should not replace the entire writing process. Always double-check and confirm the information provided by AI. Use this verified information to make your work correct and unique. This ensures your writing is both accurate and original.

Why It’s Beneficial to Use AI Writing Tools

AI writing tools are really helpful for students. They speed up writing assignments, allowing students to create drafts quickly. This is especially useful when dealing with tight deadlines or balancing multiple projects. These tools are also great for research, gathering, and organizing information efficiently, which is a big time-saver. Plus, they ensure that important aspects of a topic are not missed, making essays and reports more comprehensive. AI can also help students improve their writing skills by providing examples of clear, concise writing. For those who struggle with structuring essays or articles, AI tools offer templates and suggestions. Overall, AI writing tools are valuable for educational purposes, helping students to write more effectively and learn better research skills.

61 Executive Blvd Farmingdale, New York(NY), 11735

[email protected] [email protected]

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Paul Krugman

Meat, Freedom and Ron DeSantis

By Paul Krugman

Opinion Columnist

It’s possible to grow meat in a lab — to cultivate animal cells without an animal and turn them into something people can eat. However, that process is difficult and expensive. And at the moment, lab-grown meat isn’t commercially available and probably won’t be for a long time, if ever.

Still, if and when lab-grown meat, also sometimes referred to as cultured meat, makes it onto the market at less than outrageous prices, a significant number of people will probably buy it. Some will do so on ethical grounds, preferring not to have animals killed to grace their dinner plates. Others will do so in the belief that growing meat in labs does less damage to the environment than devoting acres and acres to animal grazing. And it’s at least possible that lab-grown meat will eventually be cheaper than meat from animals.

And if some people choose to consume lab-grown meat, why not? It’s a free country, right?

Not if the likes of Ron DeSantis have their way. Recently DeSantis, back to work as governor of Florida after the spectacular failure of his presidential campaign, signed a bill banning the production or sale of lab-grown meat in his state. Similar legislation is under consideration in several states.

On one level, this could be seen as a trivial story — a crackdown on an industry that doesn’t even exist yet. But the new Florida law is a perfect illustration of how crony capitalism, culture war, conspiracy theorizing and rejection of science have been merged — ground together, you might say — in a way that largely defines American conservatism today.

First, it puts the lie to any claim that the right is the side standing firm for limited government; government doesn’t get much more intrusive than having politicians tell you what you can and can’t eat.

Who’s behind the ban? Remember when a group of Texas ranchers sued Oprah Winfrey over a show warning about the risks of mad cow disease that they said cost them millions? It’s hard to imagine that today, meat industry fears about losing market share to lab meat aren’t playing a role. And such concerns about market share aren’t necessarily silly. Look at the rise of plant-based milk, which in 2020 accounted for 15 percent of the milk market.

But politicians who claim to worship free markets should be vehemently opposed to any attempt to suppress innovation when it might hurt established interests, which is what this amounts to. Why aren’t they?

Part of the answer, of course, is that many never truly believed in freedom — only freedom for some. Beyond that, however, meat consumption, like almost everything else, has been caught up in the culture wars.

You saw this coming years ago if you were following the most trenchant source of social observation in our times: episodes of “The Simpsons.” Way back in 1995, Lisa Simpson, having decided to become a vegetarian, was forced to sit through a classroom video titled “Meat and You: Partners in Freedom.”

Sure enough, eating or claiming to eat lots of meat has become a badge of allegiance on the right, especially among the MAGA crowd. Donald Trump Jr. once tweeted , “I’m pretty sure I ate 4 pounds of red meat yesterday,” improbable for someone who isn’t a sumo wrestler .

But even if you’re someone who insists that “real” Americans eat lots of meat, why must the meat be supplied by killing animals if an alternative becomes available? Opponents of lab-grown meat like to talk about the industrial look of cultured meat production, but what do they imagine many modern meat processing facilities look like?

And then there are the conspiracy theories. It’s a fact that getting protein from beef involves a lot more greenhouse gas emissions than getting it from other sources. It’s also a fact that under President Biden, the United States has finally been taking serious action on climate change. But in the fever swamp of the right, which these days is a pretty sizable bloc of Republican commentators and politicians, opposition to Biden’s eminently reasonable climate policy has resulted in an assortment of wild claims, including one that Biden was going to put limits on Americans’ burger consumption.

And have you heard about how global elites are going to force us to start eating insects ?

By the way, I’m not a vegetarian and have no intention of eating bugs. But I respect other people’s choices — which right-wing politicians increasingly don’t.

And aside from demonstrating that many right-wingers are actually enemies, not defenders, of freedom, the lab-meat story is yet another indicator of the decline of American conservatism as a principled movement.

Look, I’m not an admirer of Ronald Reagan, who I believe did a lot of harm as president, but at least Reaganism was about real policy issues like tax rates and regulation. The people who cast themselves as Reagan’s successors, however, seem uninterested in serious policymaking. For a lot of them, politics is a form of live-action role play. It’s not even about “owning” those they term the elites; it’s about perpetually jousting with a fantasy version of what elites supposedly want.

But while they may not care about reality, reality cares about them. Their deep unseriousness can do — and is already doing — a great deal of damage to America and the world.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Paul Krugman has been an Opinion columnist since 2000 and is also a distinguished professor at the City University of New York Graduate Center. He won the 2008 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his work on international trade and economic geography. @ PaulKrugman

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- FT App on Android & iOS

- FirstFT: the day's biggest stories

- 20+ curated newsletters

- Follow topics & set alerts with myFT

- FT Videos & Podcasts

- 20 monthly gift articles to share

- Lex: FT's flagship investment column

- 15+ Premium newsletters by leading experts

- FT Digital Edition: our digitised print edition

- Weekday Print Edition

- Videos & Podcasts

- Premium newsletters

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Everything in Premium Digital

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- 10 monthly gift articles to share

- Everything in Print

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Narrative Essays

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is a narrative essay?

When writing a narrative essay, one might think of it as telling a story. These essays are often anecdotal, experiential, and personal—allowing students to express themselves in a creative and, quite often, moving ways.

Here are some guidelines for writing a narrative essay.

- If written as a story, the essay should include all the parts of a story.

This means that you must include an introduction, plot, characters, setting, climax, and conclusion.

- When would a narrative essay not be written as a story?

A good example of this is when an instructor asks a student to write a book report. Obviously, this would not necessarily follow the pattern of a story and would focus on providing an informative narrative for the reader.

- The essay should have a purpose.

Make a point! Think of this as the thesis of your story. If there is no point to what you are narrating, why narrate it at all?

- The essay should be written from a clear point of view.

It is quite common for narrative essays to be written from the standpoint of the author; however, this is not the sole perspective to be considered. Creativity in narrative essays oftentimes manifests itself in the form of authorial perspective.

- Use clear and concise language throughout the essay.

Much like the descriptive essay, narrative essays are effective when the language is carefully, particularly, and artfully chosen. Use specific language to evoke specific emotions and senses in the reader.

- The use of the first person pronoun ‘I’ is welcomed.

Do not abuse this guideline! Though it is welcomed it is not necessary—nor should it be overused for lack of clearer diction.

- As always, be organized!

Have a clear introduction that sets the tone for the remainder of the essay. Do not leave the reader guessing about the purpose of your narrative. Remember, you are in control of the essay, so guide it where you desire (just make sure your audience can follow your lead).

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Natural language boosts LLM performance in coding, planning, and robotics

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

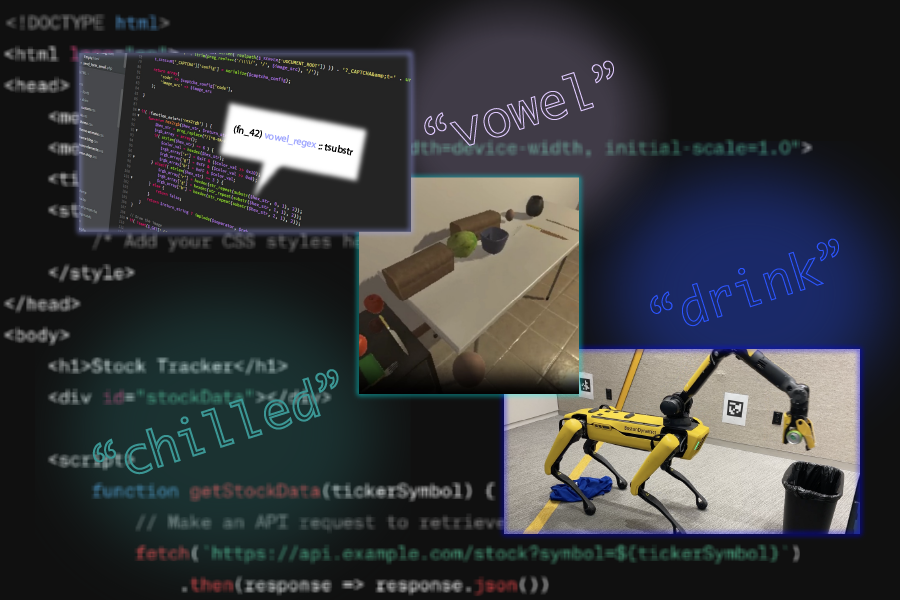

Large language models (LLMs) are becoming increasingly useful for programming and robotics tasks, but for more complicated reasoning problems, the gap between these systems and humans looms large. Without the ability to learn new concepts like humans do, these systems fail to form good abstractions — essentially, high-level representations of complex concepts that skip less-important details — and thus sputter when asked to do more sophisticated tasks. Luckily, MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) researchers have found a treasure trove of abstractions within natural language. In three papers to be presented at the International Conference on Learning Representations this month, the group shows how our everyday words are a rich source of context for language models, helping them build better overarching representations for code synthesis, AI planning, and robotic navigation and manipulation. The three separate frameworks build libraries of abstractions for their given task: LILO (library induction from language observations) can synthesize, compress, and document code; Ada (action domain acquisition) explores sequential decision-making for artificial intelligence agents; and LGA (language-guided abstraction) helps robots better understand their environments to develop more feasible plans. Each system is a neurosymbolic method, a type of AI that blends human-like neural networks and program-like logical components. LILO: A neurosymbolic framework that codes Large language models can be used to quickly write solutions to small-scale coding tasks, but cannot yet architect entire software libraries like the ones written by human software engineers. To take their software development capabilities further, AI models need to refactor (cut down and combine) code into libraries of succinct, readable, and reusable programs. Refactoring tools like the previously developed MIT-led Stitch algorithm can automatically identify abstractions, so, in a nod to the Disney movie “Lilo & Stitch,” CSAIL researchers combined these algorithmic refactoring approaches with LLMs. Their neurosymbolic method LILO uses a standard LLM to write code, then pairs it with Stitch to find abstractions that are comprehensively documented in a library. LILO’s unique emphasis on natural language allows the system to do tasks that require human-like commonsense knowledge, such as identifying and removing all vowels from a string of code and drawing a snowflake. In both cases, the CSAIL system outperformed standalone LLMs, as well as a previous library learning algorithm from MIT called DreamCoder, indicating its ability to build a deeper understanding of the words within prompts. These encouraging results point to how LILO could assist with things like writing programs to manipulate documents like Excel spreadsheets, helping AI answer questions about visuals, and drawing 2D graphics.

“Language models prefer to work with functions that are named in natural language,” says Gabe Grand SM '23, an MIT PhD student in electrical engineering and computer science, CSAIL affiliate, and lead author on the research. “Our work creates more straightforward abstractions for language models and assigns natural language names and documentation to each one, leading to more interpretable code for programmers and improved system performance.”

When prompted on a programming task, LILO first uses an LLM to quickly propose solutions based on data it was trained on, and then the system slowly searches more exhaustively for outside solutions. Next, Stitch efficiently identifies common structures within the code and pulls out useful abstractions. These are then automatically named and documented by LILO, resulting in simplified programs that can be used by the system to solve more complex tasks.

The MIT framework writes programs in domain-specific programming languages, like Logo, a language developed at MIT in the 1970s to teach children about programming. Scaling up automated refactoring algorithms to handle more general programming languages like Python will be a focus for future research. Still, their work represents a step forward for how language models can facilitate increasingly elaborate coding activities. Ada: Natural language guides AI task planning Just like in programming, AI models that automate multi-step tasks in households and command-based video games lack abstractions. Imagine you’re cooking breakfast and ask your roommate to bring a hot egg to the table — they’ll intuitively abstract their background knowledge about cooking in your kitchen into a sequence of actions. In contrast, an LLM trained on similar information will still struggle to reason about what they need to build a flexible plan. Named after the famed mathematician Ada Lovelace, who many consider the world’s first programmer, the CSAIL-led “Ada” framework makes headway on this issue by developing libraries of useful plans for virtual kitchen chores and gaming. The method trains on potential tasks and their natural language descriptions, then a language model proposes action abstractions from this dataset. A human operator scores and filters the best plans into a library, so that the best possible actions can be implemented into hierarchical plans for different tasks. “Traditionally, large language models have struggled with more complex tasks because of problems like reasoning about abstractions,” says Ada lead researcher Lio Wong, an MIT graduate student in brain and cognitive sciences, CSAIL affiliate, and LILO coauthor. “But we can combine the tools that software engineers and roboticists use with LLMs to solve hard problems, such as decision-making in virtual environments.”

When the researchers incorporated the widely-used large language model GPT-4 into Ada, the system completed more tasks in a kitchen simulator and Mini Minecraft than the AI decision-making baseline “Code as Policies.” Ada used the background information hidden within natural language to understand how to place chilled wine in a cabinet and craft a bed. The results indicated a staggering 59 and 89 percent task accuracy improvement, respectively. With this success, the researchers hope to generalize their work to real-world homes, with the hopes that Ada could assist with other household tasks and aid multiple robots in a kitchen. For now, its key limitation is that it uses a generic LLM, so the CSAIL team wants to apply a more powerful, fine-tuned language model that could assist with more extensive planning. Wong and her colleagues are also considering combining Ada with a robotic manipulation framework fresh out of CSAIL: LGA (language-guided abstraction). Language-guided abstraction: Representations for robotic tasks Andi Peng SM ’23, an MIT graduate student in electrical engineering and computer science and CSAIL affiliate, and her coauthors designed a method to help machines interpret their surroundings more like humans, cutting out unnecessary details in a complex environment like a factory or kitchen. Just like LILO and Ada, LGA has a novel focus on how natural language leads us to those better abstractions. In these more unstructured environments, a robot will need some common sense about what it’s tasked with, even with basic training beforehand. Ask a robot to hand you a bowl, for instance, and the machine will need a general understanding of which features are important within its surroundings. From there, it can reason about how to give you the item you want.

In LGA’s case, humans first provide a pre-trained language model with a general task description using natural language, like “bring me my hat.” Then, the model translates this information into abstractions about the essential elements needed to perform this task. Finally, an imitation policy trained on a few demonstrations can implement these abstractions to guide a robot to grab the desired item. Previous work required a person to take extensive notes on different manipulation tasks to pre-train a robot, which can be expensive. Remarkably, LGA guides language models to produce abstractions similar to those of a human annotator, but in less time. To illustrate this, LGA developed robotic policies to help Boston Dynamics’ Spot quadruped pick up fruits and throw drinks in a recycling bin. These experiments show how the MIT-developed method can scan the world and develop effective plans in unstructured environments, potentially guiding autonomous vehicles on the road and robots working in factories and kitchens.

“In robotics, a truth we often disregard is how much we need to refine our data to make a robot useful in the real world,” says Peng. “Beyond simply memorizing what’s in an image for training robots to perform tasks, we wanted to leverage computer vision and captioning models in conjunction with language. By producing text captions from what a robot sees, we show that language models can essentially build important world knowledge for a robot.” The challenge for LGA is that some behaviors can’t be explained in language, making certain tasks underspecified. To expand how they represent features in an environment, Peng and her colleagues are considering incorporating multimodal visualization interfaces into their work. In the meantime, LGA provides a way for robots to gain a better feel for their surroundings when giving humans a helping hand.

An “exciting frontier” in AI

“Library learning represents one of the most exciting frontiers in artificial intelligence, offering a path towards discovering and reasoning over compositional abstractions,” says assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Robert Hawkins, who was not involved with the papers. Hawkins notes that previous techniques exploring this subject have been “too computationally expensive to use at scale” and have an issue with the lambdas, or keywords used to describe new functions in many languages, that they generate. “They tend to produce opaque 'lambda salads,' big piles of hard-to-interpret functions. These recent papers demonstrate a compelling way forward by placing large language models in an interactive loop with symbolic search, compression, and planning algorithms. This work enables the rapid acquisition of more interpretable and adaptive libraries for the task at hand.” By building libraries of high-quality code abstractions using natural language, the three neurosymbolic methods make it easier for language models to tackle more elaborate problems and environments in the future. This deeper understanding of the precise keywords within a prompt presents a path forward in developing more human-like AI models. MIT CSAIL members are senior authors for each paper: Joshua Tenenbaum, a professor of brain and cognitive sciences, for both LILO and Ada; Julie Shah, head of the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, for LGA; and Jacob Andreas, associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science, for all three. The additional MIT authors are all PhD students: Maddy Bowers and Theo X. Olausson for LILO, Jiayuan Mao and Pratyusha Sharma for Ada, and Belinda Z. Li for LGA. Muxin Liu of Harvey Mudd College was a coauthor on LILO; Zachary Siegel of Princeton University, Jaihai Feng of the University of California at Berkeley, and Noa Korneev of Microsoft were coauthors on Ada; and Ilia Sucholutsky, Theodore R. Sumers, and Thomas L. Griffiths of Princeton were coauthors on LGA. LILO and Ada were supported, in part, by MIT Quest for Intelligence, the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab, Intel, U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and the U.S. Office of Naval Research, with the latter project also receiving funding from the Center for Brains, Minds and Machines. LGA received funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation, Open Philanthropy, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the U.S. Department of Defense.

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Jacob Andreas

- Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL)

- MIT Language and Intelligence Group

- Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines

- Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

- Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Related Topics

- Computer science and technology

- Artificial intelligence

- Natural language processing

- Electrical Engineering & Computer Science (eecs)

- Programming

- Human-computer interaction