- Study With Us

Dissertation Examples

- Undergraduate Research Opportunities

- Student Voice

- Peer-to-Peer Support

- The Econverse Podcast

- Events and Seminars

- China School Website

- Malaysia School Website

- Email this Page

Students in the School of Economics at the University of Nottingham consistently produce work of a very high standard in the form of coursework essays, dissertations, research work and policy articles.

Below are some examples of the excellent work produced by some of our students. The authors have agreed for their work to be made available as examples of good practice.

Undergraduate dissertations

- The Causal Impact of Education on Crime Rates: A Recent US Analysis . Emily Taylor, BSc Hons Economics, 2022

- Does a joint income taxation system for married couples disincentivise the female labour supply? Jodie Gollop, BA Hons Economics with German, 2022

- Conditional cooperation between the young and old and the influence of work experience, charitable giving, and social identity . Rachel Moffat, BSc Hons Economics, 2021

- An Extended Literature Review on the Contribution of Economic Institutions to the Great Divergence in the 19th Century . Jessica Richens, BSc Hons Economics, 2021

- Does difference help make a difference? Examining whether young trustees and female trustees affect charities’ financial performance. Chris Hyland, BSc Hons Economics, 2021

Postgraduate dissertations

- The impact of Covid-19 on the public and health expenditure gradient in mortality in England . Alexander Waller, MSc Economic Development & Policy Analysis, 2022

- Impact of the Child Support Grant on Nutritional Outcomes in South Africa: Is there a ‘pregnancy support’ effect? . Claire Lynam, MSc Development Economics, 2022

- An Empirical Analysis of the Volatility Spillovers between Commodity Markets, Exchange Rates, and the Sovereign CDS Spreads of Commodity Exporters . Alfie Fox-Heaton, MSc Financial Economics, 2022

- The 2005 Atlantic Hurricane Season and Labour Market Transitions . Edward Allenby, MSc Economics, 2022

- The scope of international agreements . Sophia Vaaßen, MSc International Economics, 2022

Thank you to all those students who have agreed to have their work showcased in this way.

School of Economics

Sir Clive Granger Building University of Nottingham University Park Nottingham, NG7 2RD

Legal information

- Terms and conditions

- Posting rules

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Charity gateway

- Cookie policy

Connect with the University of Nottingham through social media and our blogs .

- Subject Guides

Academic writing: a practical guide

Dissertations.

- Academic writing

- The writing process

- Academic writing style

- Structure & cohesion

- Criticality in academic writing

- Working with evidence

- Referencing

- Assessment & feedback

- Reflective writing

- Examination writing

- Academic posters

- Feedback on Structure and Organisation

- Feedback on Argument, Analysis, and Critical Thinking

- Feedback on Writing Style and Clarity

- Feedback on Referencing and Research

- Feedback on Presentation and Proofreading

Dissertations are a part of many degree programmes, completed in the final year of undergraduate studies or the final months of a taught masters-level degree.

Introduction to dissertations

What is a dissertation.

A dissertation is usually a long-term project to produce a long-form piece of writing; think of it a little like an extended, structured assignment. In some subjects (typically the sciences), it might be called a project instead.

Work on an undergraduate dissertation is often spread out over the final year. For a masters dissertation, you'll start thinking about it early in your course and work on it throughout the year.

You might carry out your own original research, or base your dissertation on existing research literature or data sources - there are many possibilities.

What's different about a dissertation?

The main thing that sets a dissertation apart from your previous work is that it's an almost entirely independent project. You'll have some support from a supervisor, but you will spend a lot more time working on your own.

You'll also be working on your own topic that's different to your coursemate; you'll all produce a dissertation, but on different topics and, potentially, in very different ways.

Dissertations are also longer than a regular assignment, both in word count and the time that they take to complete. You'll usually have most of an academic year to work on one, and be required to produce thousands of words; that might seem like a lot, but both time and word count will disappear very quickly once you get started!

Find out more:

Key dissertation tools

Digital tools.

There are lots of tools, software and apps that can help you get through the dissertation process. Before you start, make sure you collect the key tools ready to:

- use your time efficiently

- organise yourself and your materials

- manage your writing

- be less stressed

Here's an overview of some useful tools:

Digital tools for your dissertation [Google Slides]

Setting up your document

Formatting and how you set up your document is also very important for a long piece of work like a dissertation, research project or thesis. Find tips and advice on our text processing guide:

University of York past Undergraduate and Masters dissertations

If you are a University of York student, you can access a selection of digitised undergraduate dissertations for certain subjects:

- History

- History of Art

- Social Policy and Social Work

The Library also has digitised Masters dissertations for the following subjects:

- Archaeology

- Centre for Eighteenth-Century Studies

- Centre for Medieval Studies

- Centre for Renaissance and Early Modern Studies

- Centre for Women's Studies

- English and Related Literature

- Health Sciences

- History of Art

- Hull York Medical School

- Language and Linguistic Science

- School for Business and Society

- School of Social and Political Sciences

Dissertation top tips

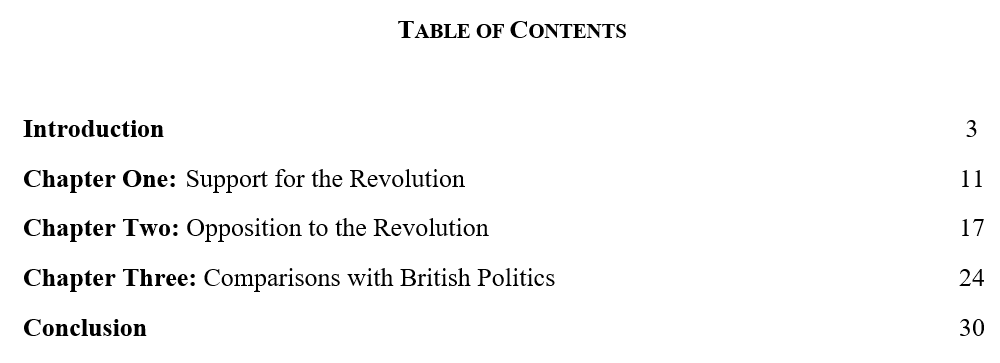

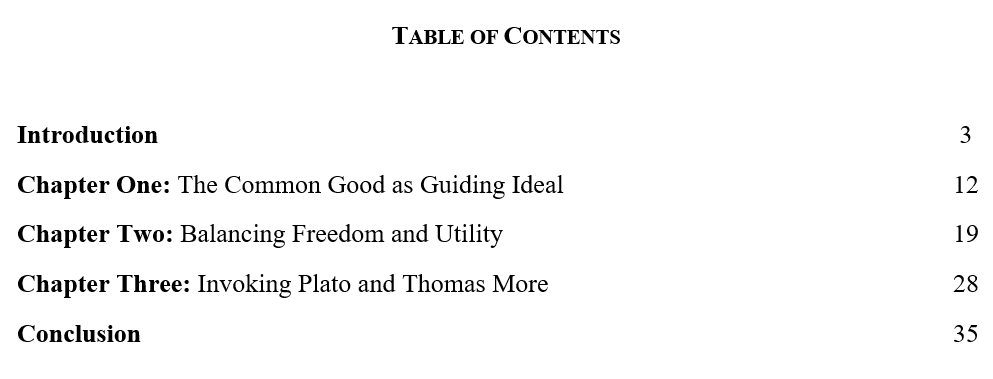

Many dissertations are structured into four key sections:

- introduction & literature review

There are many different types of dissertation, which don't all use this structure, so make sure you check your dissertation guidance. However, elements of these sections are common in all dissertation types.

Dissertations that are an extended literature review do not involve data collection, thus do not have a methods or result section. Instead they have chapters that explore concepts/theories and result in a conclusion section. Check your dissertation module handbook and all information given to see what your dissertation involves.

Introduction & literature review

The Introduction and Literature Review give the context for your dissertation:

- What topic did you investigate?

- What do we already know about this topic?

- What are your research questions and hypotheses?

Sometimes these are two separate sections, and sometimes the Literature Review is integrated into the Introduction. Check your guidelines to find out what you need to do.

Literature Review Top Tips [YouTube] | Literature Review Top Tips transcript [Google Doc]

The Method section tells the reader what you did and why.

- Include enough detail so that someone else could replicate your study.

- Visual elements can help present your method clearly. For example, summarise participant demographic data in a table or visualise the procedure in a diagram.

- Show critical analysis by justifying your choices. For example, why is your test/questionnaire/equipment appropriate for this study?

- If your study requires ethical approval, include these details in this section.

Methodology Top Tips [YouTube] | Methodology Top Tips transcript [Google Doc]

More resources to help you plan and write the methodology:

The Results tells us what you found out .

It's an objective presentation of your research findings. Don’t explain the results in detail here - you’ll do that in the discussion section.

Results Top Tips [YouTube] | Results Top Tips transcript [Google Doc]

The Discussion is where you explain and interpret your results - what do your findings mean?

This section involves a lot of critical analysis. You're not just presenting your findings, but putting them together with findings from other research to build your argument about what the findings mean.

Discussion Top Tips [YouTube] | Discussion Top Tips transcript [Google Doc]

Conclusions are a part of many dissertations and/or research projects. Check your module information to see if you are required to write one. Some dissertations/projects have concluding remarks in their discussion section. See the slides below for more information on writing conclusions in dissertations.

Conclusions in dissertations [Google Slides]

The abstract is a short summary of the whole dissertation that goes at the start of the document. It gives an overview of your research and helps readers decide if it’s relevant to their needs.

Even though it appears at the start of the document, write the abstract last. It summarises the whole dissertation, so you need to finish the main body before you can summarise it in the abstract.

Usually the abstract follows a very similar structure to the dissertation, with one or two sentences each to show the aims, methods, key results and conclusions drawn. Some subjects use headings within the abstract. Even if you don’t use these in your final abstract, headings can help you to plan a clear structure.

Abstract Top Tips [YouTube] | Abstract Top Tips transcript [Google Doc]

Watch all of our Dissertation Top Tips videos in one handy playlist:

Research reports, that are often found in science subjects, follow the same structure, so the tips in this tutorial also apply to dissertations:

Other support for dissertation writing

Online resources.

The general writing pages of this site offer guidance that can be applied to all types of writing, including dissertations. Also check your department guidance and VLE sites for tailored resources.

Other useful resources for dissertation writing:

Appointments and workshops

There is a lot of support available in departments for dissertation production, which includes your dissertation supervisor, academic supervisor and, when appropriate, staff teaching in the research methods modules.

You can also access central writing and skills support:

- << Previous: Reports

- Next: Reflective writing >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2024 4:02 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/academic-writing

- Cambridge Libraries

Physical & Digital Collections

Theses & dissertations: home, access to theses and dissertations from other institutions and from the university of cambridge.

This guide provides information on searching for theses of Cambridge PhDs and for theses of UK universities and universities abroad.

For information and guidance on depositing your thesis as a cambridge phd, visit the cambridge office of scholarly communication pages on theses here ., this guide gives essential information on how to obtain theses using the british library's ethos service. .

On the last weekend of October, the British Library became the victim of a major cyber-attack. Essential digital services including the BL catalogue, website and online learning resources went dark, with research services like the EThOS collection of more than 600,000 doctoral theses suddenly unavailable. The BL state that they anticipate restoring more services in the next few weeks, but disruption to certain services is now expected to persist for several months. For the latest news on the attack and information on the restoration of services, please follow the BL blog here: Knowledge Matters blog and access the LibGuide page here: British Library Outage Update - Electronic Legal Deposit - LibGuides at University of Cambridge Subject Libraries

A full list of resources for searching theses online is provided by the Cambridge A-Z, available here .

University of Cambridge theses

Finding a cambridge phd thesis online via the institutional repository.

The University's institutional repository, Apollo , holds full-text digital versions of over 11,000 Cambridge PhD theses and is a rapidly growing collection deposited by Cambridge Ph.D. graduates. Theses in Apollo can be browsed via this link . More information on how to access theses by University of Cambridge students can be found on the access to Cambridge theses webpage. The requirement for impending PhD graduates to deposit a digital version in order to graduate means the repository will be increasing at a rate of approximately 1,000 per year from this source. About 200 theses are added annually through requests to make theses Open Access or via requests to digitize a thesis in printed format.

Locating and obtaining a copy of a Cambridge PhD thesis (not yet available via the repository)

Theses can be searched in iDiscover . Guidance on searching for theses in iDiscover can be found here . Requests for consultation of printed theses, not available online, should be made at the Manuscripts Reading Room (Email: [email protected] Telephone: +44 (0)1223 333143). Further information on the University Library's theses, dissertations and prize essays collections can be consulted at this link .

Researchers can order a copy of an unpublished thesis which was deposited in print form either through the Library’s Digital Content Unit via the image request form , or, if the thesis has been digitised, it may be available in the Apollo repository. Copies of theses may be provided to researchers in accordance with the law and in a manner that is common across UK libraries. The law allows us to provide whole copies of unpublished theses to individuals as long as they sign a declaration saying that it is for non-commercial research or private study.

How to make your thesis available online through Cambridge's institutional repository

Are you a Cambridge alumni and wish to make your Ph.D. thesis available online? You can do this by depositing it in Apollo the University's institutional repository. Click here for further information on how to proceed. Current Ph.D students at the University of Cambridge can find further information about the requirements to deposit theses on the Office of Scholarly Communication theses webpages.

UK Theses and Dissertations

Electronic copies of Ph.D. theses submitted at over 100 UK universities are obtainable from EThOS , a service set up to provide access to all theses from participating institutions. It achieves this by harvesting e-theses from Institutional Repositories and by digitising print theses as they are ordered by researchers using the system. Over 250,000 theses are already available in this way. Please note that it does not supply theses submitted at the universities of Cambridge or Oxford although they are listed on EThOS.

Registration with EThOS is not required to search for a thesis but is necessary to download or order one unless it is stored in the university repository rather than the British Library (in which case a link to the repository will be displayed). Many theses are available without charge on an Open Access basis but in all other cases, if you are requesting a thesis that has not yet been digitised you will be asked to meet the cost. Once a thesis has been digitised it is available for free download thereafter.

When you order a thesis it will either be immediately available for download or writing to hard copy or it will need to be digitised. If you order a thesis for digitisation, the system will manage the process and you will be informed when the thesis is available for download/preparation to hard copy.

See the Search results section of the help page for full information on interpreting search results in EThOS.

EThOS is managed by the British Library and can be found at http://ethos.bl.uk . For more information see About EThOS .

World-wide (incl. UK) theses and dissertations

Electronic versions of non-UK theses may be available from the institution at which they were submitted, sometimes on an open access basis from the institutional repository. A good starting point for discovering freely available electronic theses and dissertations beyond the UK is the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) , which facilitates searching across institutions. Information can also usually be found on the library web pages of the relevant institution.

The DART Europe etheses portal lists several thousand full-text theses from a group of European universities.

The University Library subscribes to the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (PQDT) database which from August 31 2023 is accessed on the Web of Science platform. To search this index select it from the Web of Science "Search in" drop-down list of databases (available on the Documents tab on WoS home page)

PQDT includes 2.4 million dissertation and theses citations, representing 700 leading academic institutions worldwide from 1861 to the present day. The database offers full text for most of the dissertations added since 1997 and strong retrospective full text coverage for older graduate works. Each dissertation published since July 1980 includes a 350-word abstract written by the author. Master's theses published since 1988 include 150-word abstracts.

IMPORTANT NOTE: The University Library only subscribes to the abstracting & indexing version of the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database and NOT the full text version. A fee is payable for ordering a dissertation from this source. To obtain the full text of a dissertation as a downloadable PDF you can submit your request via the University Library Inter-Library Loans department (see contact details below). NB this service is only available to full and current members of the University of Cambridge.

Alternatively you can pay yourself for the dissertation PDF on the PQDT platform. Link from Web of Science record display of any thesis to PQDT by clicking on "View Details on ProQuest". On the "Preview" page you will see an option "Order a copy" top right. This will allow you to order your own copy from ProQuest directly.

Dissertations and theses submitted at non-UK universities may also be requested on Inter-Library Loan through the Inter-Library Loans department (01223 333039 or 333080, [email protected] )

- Last Updated: Dec 20, 2023 9:47 AM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/theses

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

Academic & Employability Skills

Subscribe to academic & employability skills.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 408 other subscribers.

Email Address

Writing your dissertation - structure and sections

Posted in: dissertations

In this post, we look at the structural elements of a typical dissertation. Your department may wish you to include additional sections but the following covers all core elements you will need to work on when designing and developing your final assignment.

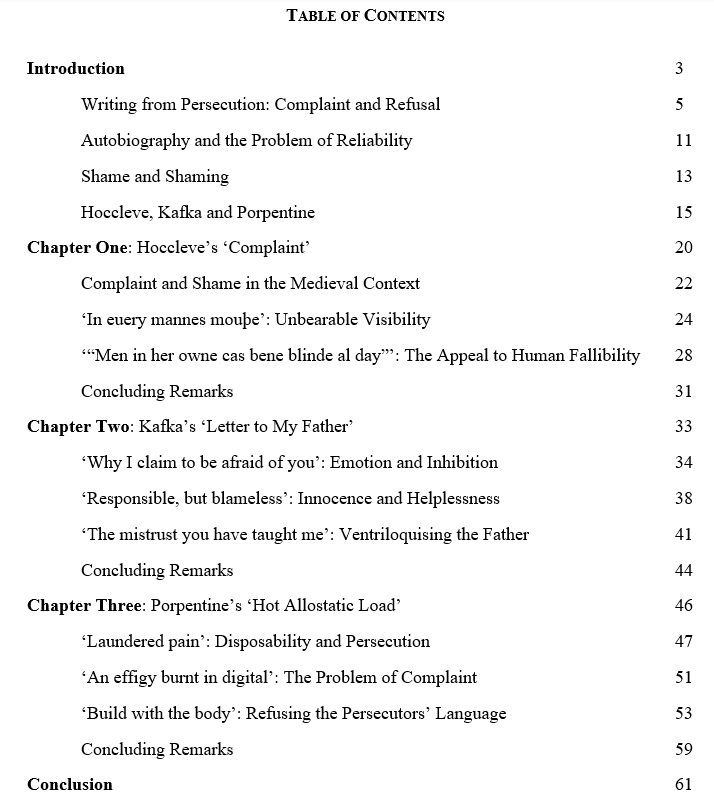

The table below illustrates a classic dissertation layout with approximate lengths for each section.

Hopkins, D. and Reid, T., 2018. The Academic Skills Handbook: Your Guid e to Success in Writing, Thinking and Communicating at University . Sage.

Your title should be clear, succinct and tell the reader exactly what your dissertation is about. If it is too vague or confusing, then it is likely your dissertation will be too vague and confusing. It is important therefore to spend time on this to ensure you get it right, and be ready to adapt to fit any changes of direction in your research or focus.

In the following examples, across a variety of subjects, you can see how the students have clearly identified the focus of their dissertation, and in some cases target a problem that they will address:

An econometric analysis of the demand for road transport within the united Kingdom from 1965 to 2000

To what extent does payment card fraud affect UK bank profitability and bank stakeholders? Does this justify fraud prevention?

A meta-analysis of implant materials for intervertebral disc replacement and regeneration.

The role of ethnic institutions in social development; the case of Mombasa, Kenya.

Why haven’t biomass crops been adopted more widely as a source of renewable energy in the United Kingdom?

Mapping the criminal mind: Profiling and its limitation.

The Relative Effectiveness of Interferon Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C

Under what conditions did the European Union exhibit leadership in international climate change negotiations from 1992-1997, 1997-2005 and 2005-Copenhagen respectively?

The first thing your reader will read (after the title) is your abstract. However, you need to write this last. Your abstract is a summary of the whole project, and will include aims and objectives, methods, results and conclusions. You cannot write this until you have completed your write-up.

Introduction

Your introduction should include the same elements found in most academic essay or report assignments, with the possible inclusion of research questions. The aim of the introduction is to set the scene, contextualise your research, introduce your focus topic and research questions, and tell the reader what you will be covering. It should move from the general and work towards the specific. You should include the following:

- Attention-grabbing statement (a controversy, a topical issue, a contentious view, a recent problem etc)

- Background and context

- Introduce the topic, key theories, concepts, terms of reference, practices, (advocates and critic)

- Introduce the problem and focus of your research

- Set out your research question(s) (this could be set out in a separate section)

- Your approach to answering your research questions.

Literature review

Your literature review is the section of your report where you show what is already known about the area under investigation and demonstrate the need for your particular study. This is a significant section in your dissertation (30%) and you should allow plenty of time to carry out a thorough exploration of your focus topic and use it to help you identify a specific problem and formulate your research questions.

You should approach the literature review with the critical analysis dial turned up to full volume. This is not simply a description, list, or summary of everything you have read. Instead, it is a synthesis of your reading, and should include analysis and evaluation of readings, evidence, studies and data, cases, real world applications and views/opinions expressed. Your supervisor is looking for this detailed critical approach in your literature review, where you unpack sources, identify strengths and weaknesses and find gaps in the research.

In other words, your literature review is your opportunity to show the reader why your paper is important and your research is significant, as it addresses the gap or on-going issue you have uncovered.

You need to tell the reader what was done. This means describing the research methods and explaining your choice. This will include information on the following:

- Are your methods qualitative or quantitative... or both? And if so, why?

- Who (if any) are the participants?

- Are you analysing any documents, systems, organisations? If so what are they and why are you analysing them?

- What did you do first, second, etc?

- What ethical considerations are there?

It is a common style convention to write what was done rather than what you did, and write it so that someone else would be able to replicate your study.

Here you describe what you have found out. You need to identify the most significant patterns in your data, and use tables and figures to support your description. Your tables and figures are a visual representation of your findings, but remember to describe what they show in your writing. There should be no critical analysis in this part (unless you have combined results and discussion sections).

Here you show the significance of your results or findings. You critically analyse what they mean, and what the implications may be. Talk about any limitations to your study, evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of your own research, and make suggestions for further studies to build on your findings. In this section, your supervisor will expect you to dig deep into your findings and critically evaluate what they mean in relation to previous studies, theories, views and opinions.

This is a summary of your project, reminding the reader of the background to your study, your objectives, and showing how you met them. Do not include any new information that you have not discussed before.

This is the list of all the sources you have cited in your dissertation. Ensure you are consistent and follow the conventions for the particular referencing system you are using. (Note: you shouldn't include books you've read but do not appear in your dissertation).

Include any extra information that your reader may like to read. It should not be essential for your reader to read them in order to understand your dissertation. Your appendices should be labelled (e.g. Appendix A, Appendix B, etc). Examples of material for the appendices include detailed data tables (summarised in your results section), the complete version of a document you have used an extract from, etc.

Share this:

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click here to cancel reply.

- Email * (we won't publish this)

Write a response

I am finding this helpful. Thank You.

It is very useful.

Glad you found it useful Adil!

I was a useful post i would like to thank you

Glad you found it useful! 🙂

Navigating the dissertation process: my tips for final years

Imagine for a moment... After months of hard work and research on a topic you're passionate about, the time has finally come to click the 'Submit' button on your dissertation. You've just completed your longest project to date as part...

8 ways to beat procrastination

Whether you’re writing an assignment or revising for exams, getting started can be hard. Fortunately, there’s lots you can do to turn procrastination into action.

My takeaways on how to write a scientific report

If you’re in your dissertation writing stage or your course includes writing a lot of scientific reports, but you don’t quite know where and how to start, the Skills Centre can help you get started. I recently attended their ‘How...

Browser does not support script.

- About the Department

- Current students

Dissertations

The dv410 dissertation is a major component of the msc programme and an important part of the learning and development process involved in postgraduate education., research design and dissertation in international development.

The DV410 dissertation is a major component of the MSc programme and an important part of the learning and development process involved in postgraduate education. The objective of DV410 is to provide students with an overview of the resources available to them to research and write a 10,000 dissertation that is topical, original, scholarly, and substantial. DV410 will provide curated dissertation pathways through LSE LIFE and Methods courses, information sessions, ID-specific disciplinary teaching, topical seminars and dissertation worksops in ST. With this in mind, students will be able to design their own training pathway and set their own learning objectives in relation to their specific needs for their dissertation. From the Autumn Term (AT) through to Summer Term (ST), students will discuss and develop their ideas in consultation with their mentor or other members of the ID department staff and have access to a range of learning resources (via DV410 Moodle page) to support and develop their individual projects from within the department and across the LSE.

Prizewinning dissertations

The archive of prizewinning dissertations showcases the best MSc dissertations from previous years. These offer a useful guide to current students on how to prepare and write a high calibre dissertation.

2022-OW (PDF) The Politics of Political Conditionality: How theEU Is Failing the Western Balkans Pim W.R.Oudejans Joint winner of Mayling Birney Prize for Best Overall Performance MSc Development Management

2022-GN (PDF) An Empirical Study of the Impact of Kenya’sFree Secondary Education Policy on Women’sEducation Nora Geiszl Winner of Prize for Best Dissertation MSc Development Management

2022-JC (PDF) Giving with one hand, taking with the other:the contradictory political economy of socialgrants in South Africa Jack Calland Prize for Best Overall Performance MSc Development Studies

2022-GL (PDF) State Versus Market: The Case of Tobacco Consumption in Eastern European and Former Soviet Transition Economies Letizia Gazzaniga Joint winner of Prize for Best Overall Performance MSc Health and International Development

2022-ER (PDF) Reproductive injustice across forced migration trajectories: Evidence from female asylum-seekers fleeing Central America’s Northern Triangle Emily Rice Joint winner of Prize for Best Overall Performance MSc Health and International Development

2022-LICB (PDF) The effects of Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) on child nutrition following an adverseweather shock: the case of Indonesia Liliana Itamar Carillo Barba Winner Prize for Best Dissertation MSc Health and International Development 2022-SC (PDF) Fiscal Responses to Conditional Debt Relief:the impact of multilateral debt cancellation on taxation patterns Sara Cucaro Joint winner of Prize for Best Dissertation MSc International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies

2022-RM (PDF) Navigating humanitarian space(s) to provideprotection and assistance to internally displacedpersons: applying the concept of ahumanitarian ‘micro-space’ to the caseof Rukban in Syria Miranda Russell Joint winner of Prize for Best Dissertation MSc International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies

2021-CC (PDF) International Remittances and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Investigating Resilient Remittance Flows from Italy during 2020 Carla Curreli Joint winner of Mayling Birney Prize for Best Overall Performance and Winner of Prize for Best Dissertation MSc Development Management

2021-NB (PDF) Reluctant respondents: Early settlement by developing countries during WTO disputes Nicholas Baxtar Joint winner of Mayling Birney Prize for Best Overall Performance MSc Development Management (Specialism: Applied Development)

2021-CD (PDF) One Belt, Many Roads? A Comparison of Power Dynamics in Chinese Infrastructure Financing of Kenya and Angola Conor Dunwoody Winner of Prize for Best Dissertation MSc Development Studies

2021-NN (PDF) Tool for peace or tool for power? Interrogating Turkish ‘water diplomacy’ in the case of Northern Cyprus Nina Newhouse Winner of Prize for Best Overall Performance MSc Development Studies

2021-CW (PDF) Exploring Legal Aid Provision for LGBTIQ+Asylum Seekers in the American Southwest from 2012-2021 Claire Wever Winner of Prize for Best Dissertation MSc International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies

2021-BP (PDF) Instrumentalising Threat; An Expansion of Biopolitical Control Over Exiles in Calais During the COVID-19 Pandemic Bethany Plant Joint winner of Prize for Best Overall Performance MSc International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies

2021-HS (PDF) A New “Green Grab”? A Multi-Scalar Analysis of Exclusion in the Lake Turkana Wind Power (LTWP) Project, Kenya Helen Sticklet Joint winner of Prize for Best Overall Performance MSc International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies

2021-GM (PDF) Fuelling policy: The Role of Public Health Policy-Support Tools in Reducing Household Air Pollution as a Risk-Factor for Non-Communicable Diseases in LMICs Georgina Morris Winner of Prize for Best Dissertation MSc Health and International Development

2021-LC (PDF) How do women garment workers employ practices of everyday resistance to challenge the patriarchal gender order of Sri Lankan society? Lois Cooper Joint winner of Prize for Best Overall Performance MSc Health and International Development

2020-LK (PDF) Can international remittances mitigate negative effects of economic shocks on education? – The case of Nigeria Lara Kasperkovitz Best Overall Performance Best Dissertation Prize International Development and Humanitarian Emergengies

“Fallen through the Cracks” The Network for Childhood Pneumonia and Challenges in Global Health Governance Eva Sigel Best Overall Performance Health and International Development

2020-AB (PDF) Fighting the ‘Forgotten’ Disease: LiST-Based Analysis of Pneumonia Prevention Interventions to Reduce Under-Five Mortality in High-Burden Countries Alexandra Bland Best Dissertation Prize Health and International Development

2020-TP (PDF) Techno-optimism and misalignment: Investigating national policy discourses on the impact of ICT in educational settings in Sub-Saharan Africa Tao Platt Best Overall Performance Development Studies

2020-HS (PDF) “We want land, all the rest is humbug”: land inheritance reform and intrahousehold dynamics in India Holly Scott Best Dissertation Prize Development Studies

2020-PE (PDF) Decent Work for All? Waste Pickers’ Collective Action Frames after Formalisation in Bogotá, Colombia Philip Edge Mayling Birney Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Management

2020-LC (PDF) Variation in Bilateral Investment Treaties: What Leads to More ‘Flexibility for Development’? Lindsey Cox Best Dissertation Prize Development Management

2019-GR (PDF) Political Economy of Industrial Policy: Analysinglongitudinal and crossnationalvariations in industrial policy in Brazil andArgentina Grace Reeve Best Overall Performance Development Studies

2019-MM (PDF) The Securitisation of Development Projects: The Indian State’s Response to the Maoist Insurgency Monica Moses Best Dissertation Prize Development Studies

2019-KM (PDF) At the End of Emergency: An Exploration of Factors Influencing Decision-making Surrounding Medical Humanitarian Exit Kaitlyn Macneil Best Overall Performance Prize Health and International Development

2019-KA (PDF) The Haitian Nutritional Paradox: Driving factors of the Double Burden of Malnutrition Khandys Agnant Best Dissertation Prize Health and International Development

2019-NL (PDF) Women in the Rwandan Parliament: Exploring Descriptive and Substantive Representation Nicole London Best Dissertation Prize Development Management

2019-CB (PDF) Post-conflict reintegration: the long-termeffects of abduction and displacement on theAcholi population of northern Uganda Charlotte Brown Mayling Birney Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Management

2019-NLeo (PDF) Making Fashion Sense: Can InternationalLabour Standards Improve Accountabilityin Globalised Fast Fashion? Nicole Leo Mayling Birney Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Management

2019-AS (PDF) Who Controls Whom? Evaluating theinvolvement of Development FinanceInstitutions (DFIs) in Build Own-Operate (BOO)Energy Projects in relation to Market Structures& Accountability Chains: The case of theBujagali Hydropower Project (BHPP) in Uganda Aya Salah Mostafa Ali Best Dissertation Prize African Development

2019-NG (PDF) Addressing barriers to treatment-seekingbehaviour during the Ebola outbreak in SierraLeone: An International Response Perspective Natasha Glendening India Best Overall Performance Prize African Development

2019-SYJ (PDF) The Traditional Global Care Chain and the Global Refugee Care Chain: A Comparative Analysis Sana Yasmine Johnson Best Dissertation Prize Best Overall Performance Prize International Development and Humanitarian Emergengies

2018-JR (PDF) Nudging, Teaching, or Coercing?: A Review of Conditionality Compliance Mechanisms on School Attendance Under Conditional Cash Transfer Programs Jonathan Rothwell Best Dissertation Prize African Development

2018-LD (PDF) A Feminist Perspective On Burundi's Land Reform Ladd Serwat Best Overall Performance African Development

2018-KL (PDF) Decentralisation: Road to Development or Bridge to Nowhere? Estimating the Effect of Devolution on Infrastructure Spending in Kenya Kurtis Lockhart Best Dissertation Prize and Mayling Birney Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Management

2018-OS (PDF) From Accountability to Quality: Evaluating the Role of the State in Monitoring Low-Cost Private Schools in Uganda and Kenya Oceane Suquet Mayling Birney Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Management

2018-LN (PDF) Water to War: An Analysis of Drought, Water Scarcity and Social Mobilization in Syria Lian Najjar Best Dissertation Prize International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies

2018-IS (PDF) “As devastating as any war”?: Discursive trends and policy-making in aid to Central America’s Northern Triangle Isabella Shraiman Best Overall Performance International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies

2017-AR (PDF) Humanitarian Reform and the Localisation Agenda:Insights from Social Movement and Organisational Theory Alice Robinson Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Performance International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies (IDHE)

2017-ACY (PDF) The Hidden Costs of a SuccessfulDevelopmental State:Prosperity and Paucity in Singapore Agnes Chew Yunquian Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Managament

2017-HK (PDF) Premature Deindustrialization and Stalled Development, the Fate of Countries Failing Structural Transformation? Helen Kirsch Winner of the Best Dissertation in Programme Development Studies

2017-HZ (PDF) ‘Bare Sexuality’ and its Effects onUnderstanding and Responding to IntimatePartner Sexual Violence in Goma, DemocraticRepublic of the Congo (DRC) Heather Zimmerman Winner of the Best Dissertation in Programme International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies (IDHE)

2017-KT (PDF) Is Good Governance a Magic Bullet?Examining Good Governance Programmes in Myanmar Khine Thu Winner of the Best Dissertation in Programme Development Managament

2017-NL (PDF) Persistent Patronage? The DownstreamElectoral Effects of Administrative Unit Creationin Uganda Nicholas Lyon Winner of the Best Dissertation in Programme African Development

2016-MV (PDF) Contract farming under competition: exploring the drivers of side selling among sugarcane farmers in Mumias Milou Vanmulken Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation Dev elopment Management

2016-JS (PDF) Resource Wealth and Democracy: Challenging the Assumptions of the Redistributive Model Janosz Schäfer Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Studies

2016-LK (PDF) Shiny Happy People: A study of the effects income relative to a reference group exerts on life satisfaction Lajos Kossuth Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Studies

2015-MP (PDF) "Corruption by design" and the management of infrastructure in Brazil: Reflections on the Programa de Aceleração ao Crescimento - PAC. Maria da Graça Ferraz de Almeida Prado Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Managment

2015-IE (PDF) Breaking Out Of the Middle-Income Trap: Assessing the Role of Structural Transformation. Ipek Ergin Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation Development Studies

2015-AML (PDF) Labour Migration, Social Movements and Regional Integration: A Comparative Study of the Role of Labour Movements in the Social Transformation of the Economic Community of West African States and the Southern African Development Community. Anne Marie Engtoft Larsen Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

2015-MM (PDF) Who Bears the Burden of Bribery? Evidence from Public Service Delivery in Kenya Michael Mbate Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation and Best Overall Performance Development Management

2015-KK (PDF) Export Processing Zones as Productive Policy: Enclave Promotion or Developmental Asset? The Case of Ghana. Kilian Koffi Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation African Development

2015-GM (PDF) Forgive and Forget? Reconciliation and Memory in Post-Biafra Nigeria. Gemma Mehmed Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies (IDHE)

2015-AS (PDF) From Sinners to Saviours: How Non-State Armed Groups use service delivery to achieve domestic legitimacy. Anthony Sequeira Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation and Best Overall Performance International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies (IDHE)

2014-NS (PDF) Anti-Corruption Agencies: Why Do Some Succeed and Most Fail? A Quantitative Political Settlement Analysis. Nicolai Schulz Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

2014-MP (PDF) International Capital Flows and Sudden Stops: a global or a domestic issue? Momchil Petkov Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

2014-TC (PDF) Democracy to Decline: do democratic changes jeopardize economic growth? Thomas Coleman Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

2014-AK (PDF) Intercultural Bilingual Education: the role of participation in improving the quality of education among indigenous communities in Chiapas, Mexico. Anni Kasari Excellent Dissertation and Best Overall Performance Development Management

2014-EL (PDF) Treaty Shopping in International Investment Arbitration: how often has it occurred and how has it been perceived by tribunals? Eunjung Lee Joint Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation Development Management

2013-SB (PDF) Refining Oil - A Way Out of the Resource Curse? Simon Baur Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

2013-NI (PDF) The Rise of ‘Murky Protectionism’: Changing Patterns of Trade-Related Industrial Policies in Developing Countries: A case study of Indonesia. Nicholas Intscher Joint Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation and Best Overall Performance Development Studies

2013-JF (PDF) Why Settle for Less? An Analysis of Settlement in WTO Disputes. Jillian Feirson Joint Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation Development Studies

2013-LH (PDF) Corporate Social Responsibility in Mining: The effects of external pressures and corporate leadership. Leah Henderson Joint Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation Development Studies

2013-BM (PDF) Estimating incumbency advantages in African politics: Regression discontinuity evidence from Zambian parliamentary and local government elections. Bobbie Macdonald Excellent Dissertation and Best Overall Performance Development Studies

WP145 (PDF) Is History Repeating Itself? A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Representation of Women in Climate Change Campaigns. Catherine Flanagan Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP144 (PDF) Disentangling the fall of a 'Dominant-Hegemonic Party Rule'. The case of Paraguay and its transition to a competitive electoral democracy. Dominica Zavala Zubizarreta Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

WP143 (PDF) Enabling Productive Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries: Critical issues in policy design. Noor Iqbal Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP142 (PDF) Beyond 'fear of death': Strategies of coping with violence and insecurity - A case study of villages in Afghanistan. Angela Jorns Joint Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation Development Studies

WP141 (PDF) What accounts for opposition party strength? Exploring party-society linkages in Zambia and Ghana. Anna Katharina Wolkenhauer Joint Winner, Best Overall Performance Development Studies

WP140 (PDF) Between Fear and Compassion: How Refugee Concerns Shape Responses to Humanitarian Emergencies - The case of Germany and Kosovo. Sebastian Sahla Joint Winner, Best Overall Performance Development Management

WP139 (PDF) Worlds Apart? Health-seeking behaviour and strategic healthcare planning in Sierra Leone. Thea Tomison Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP138 (PDF) War by Other Means? An Analysis of the Contested Terrain of Transitional Justice Under the 'Victor's Peace' in Sri Lanka. Richard Gowing Best Overall Performance and Best Dissertation International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies (IDHE)

WP137 (PDF) Social Welfare Policy - a Panacea for Peace? A Political Economy Analysis of the Role of Social Welfare Policy in Nepal's Conflict and Peace-building Process. Annie Julia Raavad Joint Winner, Best Overall Performance and Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP136 (PDF) Women and the Soft Sell: The Importance of Gender in Health Product Purchasing Decisions. Adam Alagiah Joint Winner, Best Overall Performance Development Management

WP135 (PDF) Human vs. State Security: How can Security Sector Reforms contribute to State-Building? The case of the Afghan Police Reform. Florian Weigand Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

WP134 (PDF) Evaluating the Impact of Decentralisation on Educational Outcomes: The Peruvian Case. Siegrid Holler-Neyra Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation Development Management

WP133 (PDF) Democracy and Public Good Provision: A Study of Spending Patterns in Health and Rural Development in Selected Indian States. Sreelakshmi Ramachandran Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

WP132 (PDF) Intellectual Property Rights and Technology Transfer to Developing Countries: a Reassessment of the Current Debate Marco Valenza Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP131 (PDF) Traditional or Transformational Development? A critical assessment of the potential contribution of resilience to water services in post-conflict Sub-Saharan Africa. Christopher Martin Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation International Development and Humanitarian Emergencies (IDHE)

WP128 (PDF) The demographic dividend in India: Gift or curse? A State level analysis on differeing age structure and its implications for India's economic growth prospects. Vasundhra Thakurd Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

WP127 (PDF) When Passion Dries Out, Reason Takes Control: A Temporal Study of Rebels' Motivation in Fighting Civil Wars. Thomas Tranekaer Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

WP126 (PDF) Micro-credit - More Lifebuoy than Ladder? Understanding the role of micro-credit in coping with risk in the context of the Andhra Pradesh crisis. Anita Kumar Best Overall Performance and Best Dissertation Development Management

WP124 (PDF) Welfare Policies in Latin America: the transformation of workers into poor people. Anna Popova Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP123 (PDF) How Wide a Net? Targeting Volume and Composition in Capital Inflow Controls. Lucas Issacharoff Best Overall Performance and Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP117 (PDF) Shadow Education: Quantitative and Qualitative analysis of the impact of the educational reform (implementation of centralized standardised testing). Nataliya Borodchuk Best Overall Performance and Excellent Dissertation Development Management

WP115 (PDF) Can School Decentralization Improve Learning? Autonomy, participation and student achievement in rural Pakistan. Anila Channa Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

WP114 (PDF) Good Estimation or Good Luck? Growth Accelerations revisited. Guo Xu Best Overall Performance and Best Dissertation Development Studies

WP113 (PDF) Furthering Financial Literacy: Experimental evidence from a financial literacy program for Microfinance Clients in Bhopal, India. Anna Custers Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP112 (PDF) Consumption, Development and the Private Sector: A critical analysis of base of the pyramid (BoP) ventures. David Jackman Winner of the Prize for Best Disseration Development Management

WP106 (PDF) Reading Tea Leaves: The Impacy of Mainstreaming Fair Trade. Lindsey Bornhofft Moore Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP104 (PDF) Institutions Collide: A Study of "Caste-Based" Collective Criminality and Female Infanticide in India, 1789-1871. Maria Brun Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Studies

WP102 (PDF) Democratic Pragmatism or Green Radicalism? A critical review of the relationship between Free, Prior and Informed Consent and Policymaking for Mining. Abbi Buxton Joint Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

WP100 (PDF) Market-Led Agrarian Reform: A Beneficiary perspective of Cédula da Terra. Veronika Penciakova Joint Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Studies

WP98 (PDF) No Business like Slum Business? The Political Economy of the Continued Existence of Slums: A case study of Nairobi. Florence Dafe Joint Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation Development Studies

WP97 (PDF) Power and Choice in International Trade: How power imbalances constrain the South's choices on free trade agreements, with a case study of Uruguay. Lily Ryan-Collins Joint Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Dissertation Development Management

WP96 (PDF) Health Worker Motivation and the Role of Performance Based Finance Systems Africa: A Qualitative Study on Health Worker Motivation and the Rwandan Performance Based finance initiative in District Hospitals. Friederike Paul Joint Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Dissertation Development Management

WP95 (PDF) Crisis in the Countryside: Farmer Suicides and the Political Economy of Agrarian Distress in India. Bala Posani Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Management

WP94 (PDF) From Rebels to Politicians. Explaining Rebel-to Party Transformations after Civil War: The case of Nepal. Dominik Klapdor Winner of the Prize for Excellent Dissertation Development Management

WP92 (PDF) Guarding the State or Protecting the Economy? The Economic factors of Pakistan's Military coups. Amina Ibrahim Winner of the Prize for Best Dissertation Development Studies

WP91 (PDF) Man is the remedy of man: Constructions of Masculinity and Health-Related Behaviours among Young men in Dakar, Senegal. Sarah Helen Mathewson Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Performance Development Studies

Graduate programmes

How To Write A Dissertation Or Thesis

8 straightforward steps to craft an a-grade dissertation.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

Writing a dissertation or thesis is not a simple task. It takes time, energy and a lot of will power to get you across the finish line. It’s not easy – but it doesn’t necessarily need to be a painful process. If you understand the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis, your research journey will be a lot smoother.

In this post, I’m going to outline the big-picture process of how to write a high-quality dissertation or thesis, without losing your mind along the way. If you’re just starting your research, this post is perfect for you. Alternatively, if you’ve already submitted your proposal, this article which covers how to structure a dissertation might be more helpful.

How To Write A Dissertation: 8 Steps

- Clearly understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is

- Find a unique and valuable research topic

- Craft a convincing research proposal

- Write up a strong introduction chapter

- Review the existing literature and compile a literature review

- Design a rigorous research strategy and undertake your own research

- Present the findings of your research

- Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Step 1: Understand exactly what a dissertation is

This probably sounds like a no-brainer, but all too often, students come to us for help with their research and the underlying issue is that they don’t fully understand what a dissertation (or thesis) actually is.

So, what is a dissertation?

At its simplest, a dissertation or thesis is a formal piece of research , reflecting the standard research process . But what is the standard research process, you ask? The research process involves 4 key steps:

- Ask a very specific, well-articulated question (s) (your research topic)

- See what other researchers have said about it (if they’ve already answered it)

- If they haven’t answered it adequately, undertake your own data collection and analysis in a scientifically rigorous fashion

- Answer your original question(s), based on your analysis findings

In short, the research process is simply about asking and answering questions in a systematic fashion . This probably sounds pretty obvious, but people often think they’ve done “research”, when in fact what they have done is:

- Started with a vague, poorly articulated question

- Not taken the time to see what research has already been done regarding the question

- Collected data and opinions that support their gut and undertaken a flimsy analysis

- Drawn a shaky conclusion, based on that analysis

If you want to see the perfect example of this in action, look out for the next Facebook post where someone claims they’ve done “research”… All too often, people consider reading a few blog posts to constitute research. Its no surprise then that what they end up with is an opinion piece, not research. Okay, okay – I’ll climb off my soapbox now.

The key takeaway here is that a dissertation (or thesis) is a formal piece of research, reflecting the research process. It’s not an opinion piece , nor a place to push your agenda or try to convince someone of your position. Writing a good dissertation involves asking a question and taking a systematic, rigorous approach to answering it.

If you understand this and are comfortable leaving your opinions or preconceived ideas at the door, you’re already off to a good start!

Step 2: Find a unique, valuable research topic

As we saw, the first step of the research process is to ask a specific, well-articulated question. In other words, you need to find a research topic that asks a specific question or set of questions (these are called research questions ). Sounds easy enough, right? All you’ve got to do is identify a question or two and you’ve got a winning research topic. Well, not quite…

A good dissertation or thesis topic has a few important attributes. Specifically, a solid research topic should be:

Let’s take a closer look at these:

Attribute #1: Clear

Your research topic needs to be crystal clear about what you’re planning to research, what you want to know, and within what context. There shouldn’t be any ambiguity or vagueness about what you’ll research.

Here’s an example of a clearly articulated research topic:

An analysis of consumer-based factors influencing organisational trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms.

As you can see in the example, its crystal clear what will be analysed (factors impacting organisational trust), amongst who (consumers) and in what context (British low-cost equity brokerage firms, based online).

Need a helping hand?

Attribute #2: Unique

Your research should be asking a question(s) that hasn’t been asked before, or that hasn’t been asked in a specific context (for example, in a specific country or industry).

For example, sticking organisational trust topic above, it’s quite likely that organisational trust factors in the UK have been investigated before, but the context (online low-cost equity brokerages) could make this research unique. Therefore, the context makes this research original.

One caveat when using context as the basis for originality – you need to have a good reason to suspect that your findings in this context might be different from the existing research – otherwise, there’s no reason to warrant researching it.

Attribute #3: Important

Simply asking a unique or original question is not enough – the question needs to create value. In other words, successfully answering your research questions should provide some value to the field of research or the industry. You can’t research something just to satisfy your curiosity. It needs to make some form of contribution either to research or industry.

For example, researching the factors influencing consumer trust would create value by enabling businesses to tailor their operations and marketing to leverage factors that promote trust. In other words, it would have a clear benefit to industry.

So, how do you go about finding a unique and valuable research topic? We explain that in detail in this video post – How To Find A Research Topic . Yeah, we’ve got you covered 😊

Step 3: Write a convincing research proposal

Once you’ve pinned down a high-quality research topic, the next step is to convince your university to let you research it. No matter how awesome you think your topic is, it still needs to get the rubber stamp before you can move forward with your research. The research proposal is the tool you’ll use for this job.

So, what’s in a research proposal?

The main “job” of a research proposal is to convince your university, advisor or committee that your research topic is worthy of approval. But convince them of what? Well, this varies from university to university, but generally, they want to see that:

- You have a clearly articulated, unique and important topic (this might sound familiar…)

- You’ve done some initial reading of the existing literature relevant to your topic (i.e. a literature review)

- You have a provisional plan in terms of how you will collect data and analyse it (i.e. a methodology)

At the proposal stage, it’s (generally) not expected that you’ve extensively reviewed the existing literature , but you will need to show that you’ve done enough reading to identify a clear gap for original (unique) research. Similarly, they generally don’t expect that you have a rock-solid research methodology mapped out, but you should have an idea of whether you’ll be undertaking qualitative or quantitative analysis , and how you’ll collect your data (we’ll discuss this in more detail later).

Long story short – don’t stress about having every detail of your research meticulously thought out at the proposal stage – this will develop as you progress through your research. However, you do need to show that you’ve “done your homework” and that your research is worthy of approval .

So, how do you go about crafting a high-quality, convincing proposal? We cover that in detail in this video post – How To Write A Top-Class Research Proposal . We’ve also got a video walkthrough of two proposal examples here .

Step 4: Craft a strong introduction chapter

Once your proposal’s been approved, its time to get writing your actual dissertation or thesis! The good news is that if you put the time into crafting a high-quality proposal, you’ve already got a head start on your first three chapters – introduction, literature review and methodology – as you can use your proposal as the basis for these.

Handy sidenote – our free dissertation & thesis template is a great way to speed up your dissertation writing journey.

What’s the introduction chapter all about?

The purpose of the introduction chapter is to set the scene for your research (dare I say, to introduce it…) so that the reader understands what you’ll be researching and why it’s important. In other words, it covers the same ground as the research proposal in that it justifies your research topic.

What goes into the introduction chapter?

This can vary slightly between universities and degrees, but generally, the introduction chapter will include the following:

- A brief background to the study, explaining the overall area of research

- A problem statement , explaining what the problem is with the current state of research (in other words, where the knowledge gap exists)

- Your research questions – in other words, the specific questions your study will seek to answer (based on the knowledge gap)

- The significance of your study – in other words, why it’s important and how its findings will be useful in the world

As you can see, this all about explaining the “what” and the “why” of your research (as opposed to the “how”). So, your introduction chapter is basically the salesman of your study, “selling” your research to the first-time reader and (hopefully) getting them interested to read more.

How do I write the introduction chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this post .

Step 5: Undertake an in-depth literature review

As I mentioned earlier, you’ll need to do some initial review of the literature in Steps 2 and 3 to find your research gap and craft a convincing research proposal – but that’s just scratching the surface. Once you reach the literature review stage of your dissertation or thesis, you need to dig a lot deeper into the existing research and write up a comprehensive literature review chapter.

What’s the literature review all about?

There are two main stages in the literature review process:

Literature Review Step 1: Reading up

The first stage is for you to deep dive into the existing literature (journal articles, textbook chapters, industry reports, etc) to gain an in-depth understanding of the current state of research regarding your topic. While you don’t need to read every single article, you do need to ensure that you cover all literature that is related to your core research questions, and create a comprehensive catalogue of that literature , which you’ll use in the next step.

Reading and digesting all the relevant literature is a time consuming and intellectually demanding process. Many students underestimate just how much work goes into this step, so make sure that you allocate a good amount of time for this when planning out your research. Thankfully, there are ways to fast track the process – be sure to check out this article covering how to read journal articles quickly .

Literature Review Step 2: Writing up

Once you’ve worked through the literature and digested it all, you’ll need to write up your literature review chapter. Many students make the mistake of thinking that the literature review chapter is simply a summary of what other researchers have said. While this is partly true, a literature review is much more than just a summary. To pull off a good literature review chapter, you’ll need to achieve at least 3 things:

- You need to synthesise the existing research , not just summarise it. In other words, you need to show how different pieces of theory fit together, what’s agreed on by researchers, what’s not.

- You need to highlight a research gap that your research is going to fill. In other words, you’ve got to outline the problem so that your research topic can provide a solution.

- You need to use the existing research to inform your methodology and approach to your own research design. For example, you might use questions or Likert scales from previous studies in your your own survey design .

As you can see, a good literature review is more than just a summary of the published research. It’s the foundation on which your own research is built, so it deserves a lot of love and attention. Take the time to craft a comprehensive literature review with a suitable structure .

But, how do I actually write the literature review chapter, you ask? We cover that in detail in this video post .

Step 6: Carry out your own research

Once you’ve completed your literature review and have a sound understanding of the existing research, its time to develop your own research (finally!). You’ll design this research specifically so that you can find the answers to your unique research question.

There are two steps here – designing your research strategy and executing on it:

1 – Design your research strategy

The first step is to design your research strategy and craft a methodology chapter . I won’t get into the technicalities of the methodology chapter here, but in simple terms, this chapter is about explaining the “how” of your research. If you recall, the introduction and literature review chapters discussed the “what” and the “why”, so it makes sense that the next point to cover is the “how” –that’s what the methodology chapter is all about.

In this section, you’ll need to make firm decisions about your research design. This includes things like:

- Your research philosophy (e.g. positivism or interpretivism )

- Your overall methodology (e.g. qualitative , quantitative or mixed methods)

- Your data collection strategy (e.g. interviews , focus groups, surveys)

- Your data analysis strategy (e.g. content analysis , correlation analysis, regression)

If these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these in plain language in other posts. It’s not essential that you understand the intricacies of research design (yet!). The key takeaway here is that you’ll need to make decisions about how you’ll design your own research, and you’ll need to describe (and justify) your decisions in your methodology chapter.

2 – Execute: Collect and analyse your data

Once you’ve worked out your research design, you’ll put it into action and start collecting your data. This might mean undertaking interviews, hosting an online survey or any other data collection method. Data collection can take quite a bit of time (especially if you host in-person interviews), so be sure to factor sufficient time into your project plan for this. Oftentimes, things don’t go 100% to plan (for example, you don’t get as many survey responses as you hoped for), so bake a little extra time into your budget here.

Once you’ve collected your data, you’ll need to do some data preparation before you can sink your teeth into the analysis. For example:

- If you carry out interviews or focus groups, you’ll need to transcribe your audio data to text (i.e. a Word document).

- If you collect quantitative survey data, you’ll need to clean up your data and get it into the right format for whichever analysis software you use (for example, SPSS, R or STATA).

Once you’ve completed your data prep, you’ll undertake your analysis, using the techniques that you described in your methodology. Depending on what you find in your analysis, you might also do some additional forms of analysis that you hadn’t planned for. For example, you might see something in the data that raises new questions or that requires clarification with further analysis.

The type(s) of analysis that you’ll use depend entirely on the nature of your research and your research questions. For example:

- If your research if exploratory in nature, you’ll often use qualitative analysis techniques .

- If your research is confirmatory in nature, you’ll often use quantitative analysis techniques

- If your research involves a mix of both, you might use a mixed methods approach

Again, if these words have got your head spinning, don’t worry! We’ll explain these concepts and techniques in other posts. The key takeaway is simply that there’s no “one size fits all” for research design and methodology – it all depends on your topic, your research questions and your data. So, don’t be surprised if your study colleagues take a completely different approach to yours.

Step 7: Present your findings

Once you’ve completed your analysis, it’s time to present your findings (finally!). In a dissertation or thesis, you’ll typically present your findings in two chapters – the results chapter and the discussion chapter .

What’s the difference between the results chapter and the discussion chapter?

While these two chapters are similar, the results chapter generally just presents the processed data neatly and clearly without interpretation, while the discussion chapter explains the story the data are telling – in other words, it provides your interpretation of the results.

For example, if you were researching the factors that influence consumer trust, you might have used a quantitative approach to identify the relationship between potential factors (e.g. perceived integrity and competence of the organisation) and consumer trust. In this case:

- Your results chapter would just present the results of the statistical tests. For example, correlation results or differences between groups. In other words, the processed numbers.

- Your discussion chapter would explain what the numbers mean in relation to your research question(s). For example, Factor 1 has a weak relationship with consumer trust, while Factor 2 has a strong relationship.

Depending on the university and degree, these two chapters (results and discussion) are sometimes merged into one , so be sure to check with your institution what their preference is. Regardless of the chapter structure, this section is about presenting the findings of your research in a clear, easy to understand fashion.

Importantly, your discussion here needs to link back to your research questions (which you outlined in the introduction or literature review chapter). In other words, it needs to answer the key questions you asked (or at least attempt to answer them).

For example, if we look at the sample research topic:

In this case, the discussion section would clearly outline which factors seem to have a noteworthy influence on organisational trust. By doing so, they are answering the overarching question and fulfilling the purpose of the research .

For more information about the results chapter , check out this post for qualitative studies and this post for quantitative studies .

Step 8: The Final Step Draw a conclusion and discuss the implications

Last but not least, you’ll need to wrap up your research with the conclusion chapter . In this chapter, you’ll bring your research full circle by highlighting the key findings of your study and explaining what the implications of these findings are.

What exactly are key findings? The key findings are those findings which directly relate to your original research questions and overall research objectives (which you discussed in your introduction chapter). The implications, on the other hand, explain what your findings mean for industry, or for research in your area.

Sticking with the consumer trust topic example, the conclusion might look something like this:

Key findings

This study set out to identify which factors influence consumer-based trust in British low-cost online equity brokerage firms. The results suggest that the following factors have a large impact on consumer trust:

While the following factors have a very limited impact on consumer trust:

Notably, within the 25-30 age groups, Factors E had a noticeably larger impact, which may be explained by…

Implications

The findings having noteworthy implications for British low-cost online equity brokers. Specifically:

The large impact of Factors X and Y implies that brokers need to consider….

The limited impact of Factor E implies that brokers need to…

As you can see, the conclusion chapter is basically explaining the “what” (what your study found) and the “so what?” (what the findings mean for the industry or research). This brings the study full circle and closes off the document.

Let’s recap – how to write a dissertation or thesis

You’re still with me? Impressive! I know that this post was a long one, but hopefully you’ve learnt a thing or two about how to write a dissertation or thesis, and are now better equipped to start your own research.

To recap, the 8 steps to writing a quality dissertation (or thesis) are as follows:

- Understand what a dissertation (or thesis) is – a research project that follows the research process.

- Find a unique (original) and important research topic

- Craft a convincing dissertation or thesis research proposal

- Write a clear, compelling introduction chapter

- Undertake a thorough review of the existing research and write up a literature review

- Undertake your own research

- Present and interpret your findings

Once you’ve wrapped up the core chapters, all that’s typically left is the abstract , reference list and appendices. As always, be sure to check with your university if they have any additional requirements in terms of structure or content.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

thankfull >>>this is very useful

Thank you, it was really helpful

unquestionably, this amazing simplified way of teaching. Really , I couldn’t find in the literature words that fully explicit my great thanks to you. However, I could only say thanks a-lot.

Great to hear that – thanks for the feedback. Good luck writing your dissertation/thesis.

This is the most comprehensive explanation of how to write a dissertation. Many thanks for sharing it free of charge.

Very rich presentation. Thank you

Thanks Derek Jansen|GRADCOACH, I find it very useful guide to arrange my activities and proceed to research!

Thank you so much for such a marvelous teaching .I am so convinced that am going to write a comprehensive and a distinct masters dissertation

It is an amazing comprehensive explanation

This was straightforward. Thank you!

I can say that your explanations are simple and enlightening – understanding what you have done here is easy for me. Could you write more about the different types of research methods specific to the three methodologies: quan, qual and MM. I look forward to interacting with this website more in the future.

Thanks for the feedback and suggestions 🙂

Hello, your write ups is quite educative. However, l have challenges in going about my research questions which is below; *Building the enablers of organisational growth through effective governance and purposeful leadership.*

Very educating.

Just listening to the name of the dissertation makes the student nervous. As writing a top-quality dissertation is a difficult task as it is a lengthy topic, requires a lot of research and understanding and is usually around 10,000 to 15000 words. Sometimes due to studies, unbalanced workload or lack of research and writing skill students look for dissertation submission from professional writers.

Thank you 💕😊 very much. I was confused but your comprehensive explanation has cleared my doubts of ever presenting a good thesis. Thank you.

thank you so much, that was so useful

Hi. Where is the excel spread sheet ark?

could you please help me look at your thesis paper to enable me to do the portion that has to do with the specification

my topic is “the impact of domestic revenue mobilization.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Finding UK theses

The Bodleian Libraries hold copies of some UK theses. These are listed on SOLO and may be ordered for delivery to a reading room.

These theses are not all catalogued in a uniform way. Adding the word 'thesis' as a keyword in SOLO may help, but this is unlikely to find all theses, and may find published works based upon theses as well as unpublished theses.

Card catalogue

Some early theses accepted for higher degrees and published before 1973 are held in the Bodleian Libraries but are not yet catalogued on SOLO. These holdings can be found in the Foreign Dissertations Catalogue card index.

To request access to material in the catalogue, speak to library staff at the Main Enquiry Desk in the Lower Reading Room of the Old Bodleian Library, or contact us via [email protected] or phone (01865 277162).

Other finding aids

Proquest dissertations & theses.

You can use ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global to locate theses accepted for higher degrees at universities in the UK and Ireland since 1716. The service also provides abstracts of these theses.

Library Hub Discover

You can use Library Hub Discover to search the online catalogues of some of the UK’s largest university research libraries to see if a thesis is held by another UK library.

EThOS is the UK’s national thesis service, managed by the British Library. It aims to provide a national aggregated record of all doctoral theses awarded by UK higher education institutions, with free access to the full text of many theses. It has around 500,000 records for theses awarded by over 120 institutions.

UTREES - University Theses in Russian, Soviet, and East European Studies 1907–