Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

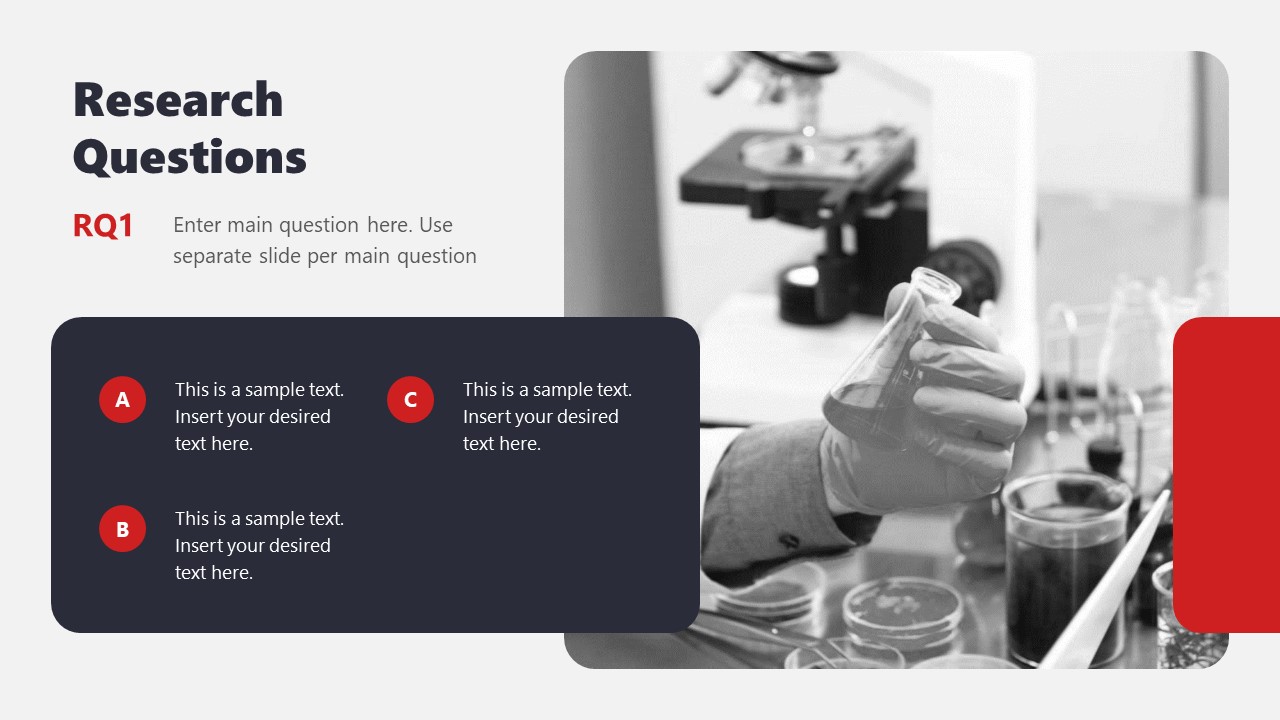

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

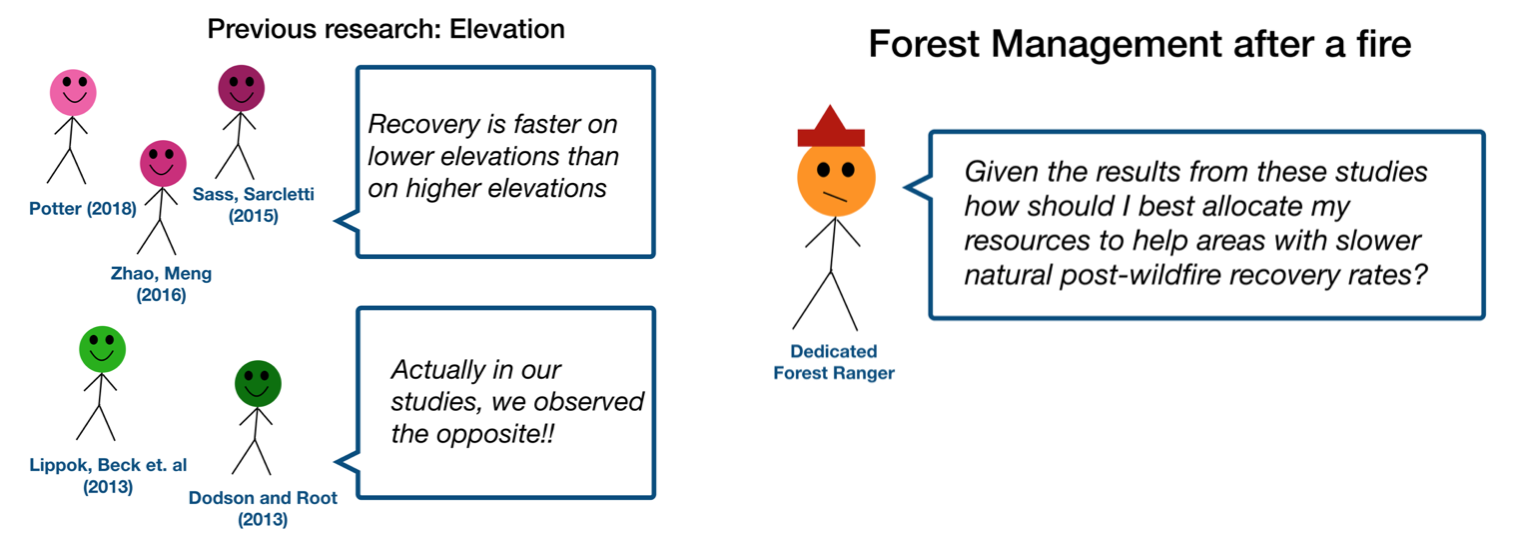

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

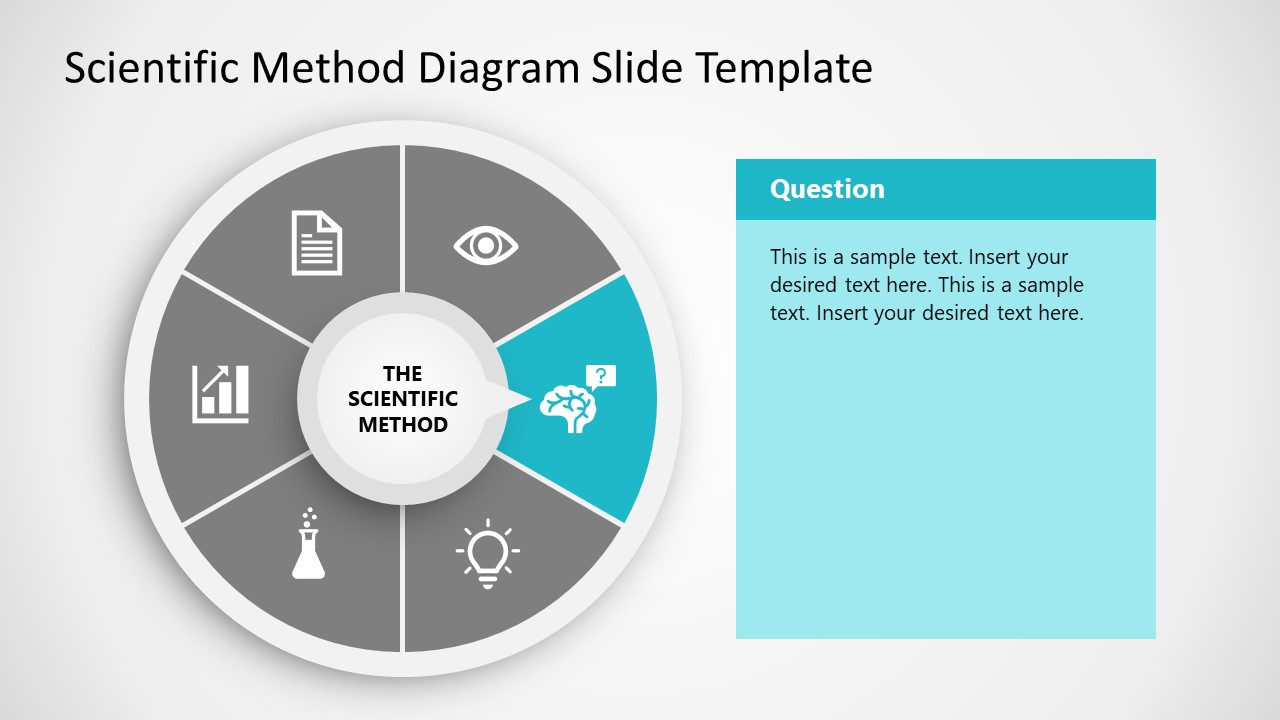

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to make a scientific presentation

Scientific presentation outlines

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk, 1. how much time do you have, 2. who will you speak to, 3. what do you want the audience to learn from your talk, step 1: outline your presentation, step 2: plan your presentation slides, step 3: make the presentation slides, slide design, text elements, animations and transitions, step 4: practice your presentation, final thoughts, frequently asked questions about preparing scientific presentations, related articles.

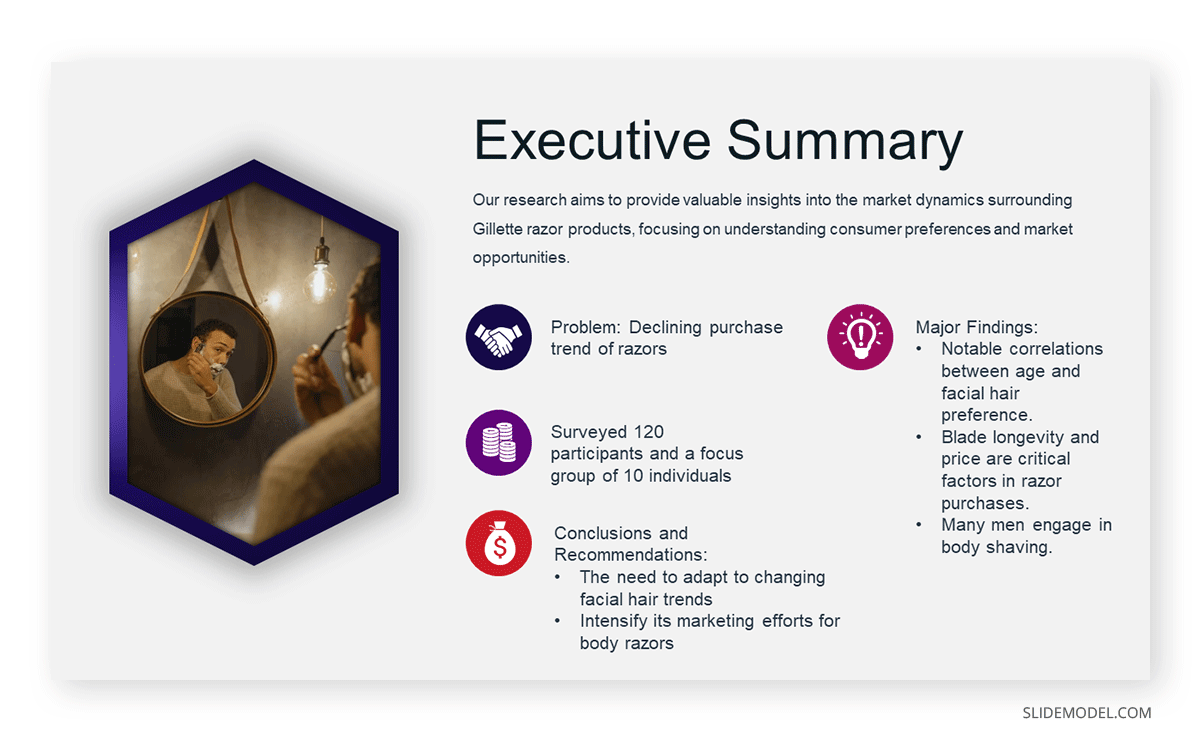

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered;

- How to outline a scientific presentation;

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation.

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

There are two main types of scientific talks:

- Your talk focuses on a single study . Typically, you tell the story of a single scientific paper. This format is common for short talks at contributed sessions in conferences.

- Your talk describes multiple studies. You tell the story of multiple scientific papers. It is crucial to have a theme that unites the studies, for example, an overarching question or problem statement, with each study representing specific but different variations of the same theme. Typically, PhD defenses, invited seminars, lectures, or talks for a prospective employer (i.e., “job talks”) fall into this category.

➡️ Learn how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The length of time you are allotted for your talk will determine whether you will discuss a single study or multiple studies, and which details to include in your story.

The background and interests of your audience will determine the narrative direction of your talk, and what devices you will use to get their attention. Will you be speaking to people specializing in your field, or will the audience also contain people from disciplines other than your own? To reach non-specialists, you will need to discuss the broader implications of your study outside your field.

The needs of the audience will also determine what technical details you will include, and the language you will use. For example, an undergraduate audience will have different needs than an audience of seasoned academics. Students will require a more comprehensive overview of background information and explanations of jargon but will need less technical methodological details.

Your goal is to speak to the majority. But, make your talk accessible to the least knowledgeable person in the room.

This is called the thesis statement, or simply the “take-home message”. Having listened to your talk, what message do you want the audience to take away from your presentation? Describe the main idea in one or two sentences. You want this theme to be present throughout your presentation. Again, the thesis statement will depend on the audience and the type of talk you are giving.

Your thesis statement will drive the narrative for your talk. By deciding the take-home message you want to convince the audience of as a result of listening to your talk, you decide how the story of your talk will flow and how you will navigate its twists and turns. The thesis statement tells you the results you need to show, which subsequently tells you the methods or studies you need to describe, which decides the angle you take in your introduction.

➡️ Learn how to write a thesis statement

The goal of your talk is that the audience leaves afterward with a clear understanding of the key take-away message of your research. To achieve that goal, you need to tell a coherent, logical story that conveys your thesis statement throughout the presentation. You can tell your story through careful preparation of your talk.

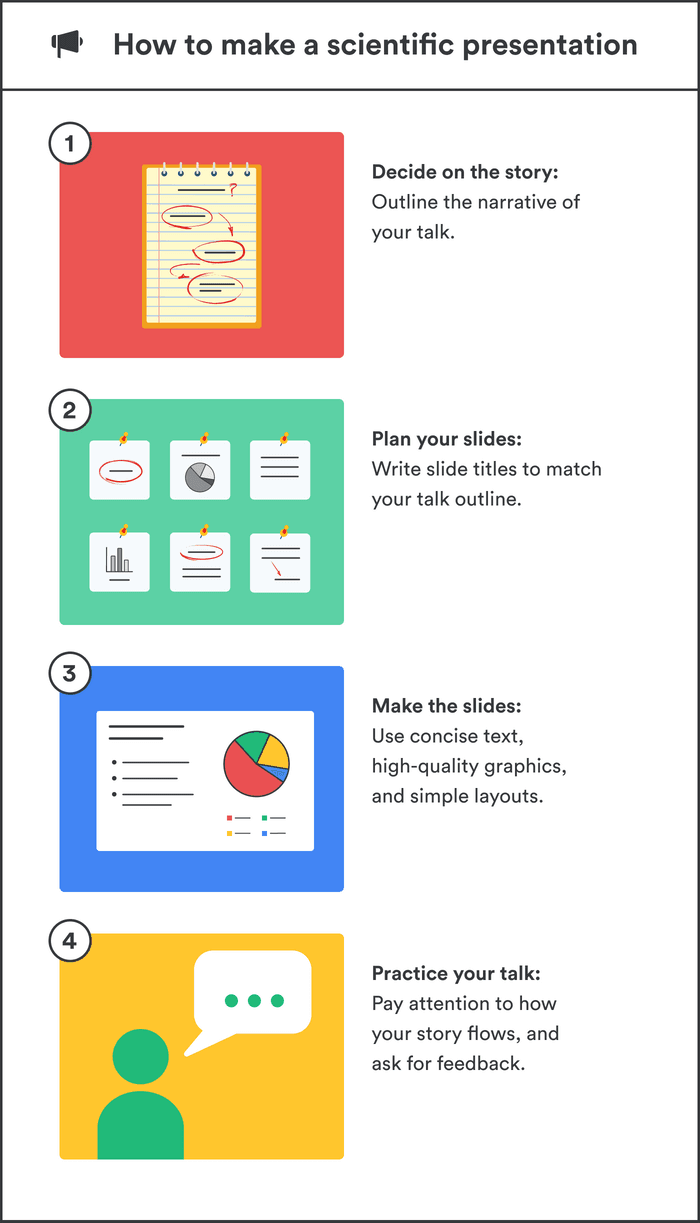

Preparation of a scientific presentation involves three separate stages: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slides, and practicing your delivery. Making the slides of your talk without first planning what you are going to say is inefficient.

Here, we provide a 4 step guide to writing your scientific presentation:

- Outline your presentation

- Plan your presentation slides

- Make the presentation slides

- Practice your presentation

Writing an outline helps you consider the key pieces of your talk and how they fit together from the beginning, preventing you from forgetting any important details. It also means you avoid changing the order of your slides multiple times, saving you time.

Plan your talk as discrete sections. In the table below, we describe the sections for a single study talk vs. a talk discussing multiple studies:

Introduction | Introduction - main idea behind all studies |

Methods | Methods of study 1 |

Results | Results of study 1 |

Summary (take-home message ) of study 1 | |

Transition to study 2 (can be a visual of your main idea that return to) | |

Brief introduction for study 2 | |

Methods of study 2 | |

Results of study 2 | |

Summary of study 2 | |

Transition to study 3 | |

Repeat format until done | |

Summary | Summary of all studies (return to your main idea) |

Conclusion | Conclusion |

The following tips apply when writing the outline of a single study talk. You can easily adapt this framework if you are writing a talk discussing multiple studies.

Introduction: Writing the introduction can be the hardest part of writing a talk. And when giving it, it’s the point where you might be at your most nervous. But preparing a good, concise introduction will settle your nerves.

The introduction tells the audience the story of why you studied your topic. A good introduction succinctly achieves four things, in the following order.

- It gives a broad perspective on the problem or topic for people in the audience who may be outside your discipline (i.e., it explains the big-picture problem motivating your study).

- It describes why you did the study, and why the audience should care.

- It gives a brief indication of how your study addressed the problem and provides the necessary background information that the audience needs to understand your work.

- It indicates what the audience will learn from the talk, and prepares them for what will come next.

A good introduction not only gives the big picture and motivations behind your study but also concisely sets the stage for what the audience will learn from the talk (e.g., the questions your work answers, and/or the hypotheses that your work tests). The end of the introduction will lead to a natural transition to the methods.

Give a broad perspective on the problem. The easiest way to start with the big picture is to think of a hook for the first slide of your presentation. A hook is an opening that gets the audience’s attention and gets them interested in your story. In science, this might take the form of a why, or a how question, or it could be a statement about a major problem or open question in your field. Other examples of hooks include quotes, short anecdotes, or interesting statistics.

Why should the audience care? Next, decide on the angle you are going to take on your hook that links to the thesis of your talk. In other words, you need to set the context, i.e., explain why the audience should care. For example, you may introduce an observation from nature, a pattern in experimental data, or a theory that you want to test. The audience must understand your motivations for the study.

Supplementary details. Once you have established the hook and angle, you need to include supplementary details to support them. For example, you might state your hypothesis. Then go into previous work and the current state of knowledge. Include citations of these studies. If you need to introduce some technical methodological details, theory, or jargon, do it here.

Conclude your introduction. The motivation for the work and background information should set the stage for the conclusion of the introduction, where you describe the goals of your study, and any hypotheses or predictions. Let the audience know what they are going to learn.

Methods: The audience will use your description of the methods to assess the approach you took in your study and to decide whether your findings are credible. Tell the story of your methods in chronological order. Use visuals to describe your methods as much as possible. If you have equations, make sure to take the time to explain them. Decide what methods to include and how you will show them. You need enough detail so that your audience will understand what you did and therefore can evaluate your approach, but avoid including superfluous details that do not support your main idea. You want to avoid the common mistake of including too much data, as the audience can read the paper(s) later.

Results: This is the evidence you present for your thesis. The audience will use the results to evaluate the support for your main idea. Choose the most important and interesting results—those that support your thesis. You don’t need to present all the results from your study (indeed, you most likely won’t have time to present them all). Break down complex results into digestible pieces, e.g., comparisons over multiple slides (more tips in the next section).

Summary: Summarize your main findings. Displaying your main findings through visuals can be effective. Emphasize the new contributions to scientific knowledge that your work makes.

Conclusion: Complete the circle by relating your conclusions to the big picture topic in your introduction—and your hook, if possible. It’s important to describe any alternative explanations for your findings. You might also speculate on future directions arising from your research. The slides that comprise your conclusion do not need to state “conclusion”. Rather, the concluding slide title should be a declarative sentence linking back to the big picture problem and your main idea.

It’s important to end well by planning a strong closure to your talk, after which you will thank the audience. Your closing statement should relate to your thesis, perhaps by stating it differently or memorably. Avoid ending awkwardly by memorizing your closing sentence.

By now, you have an outline of the story of your talk, which you can use to plan your slides. Your slides should complement and enhance what you will say. Use the following steps to prepare your slides.

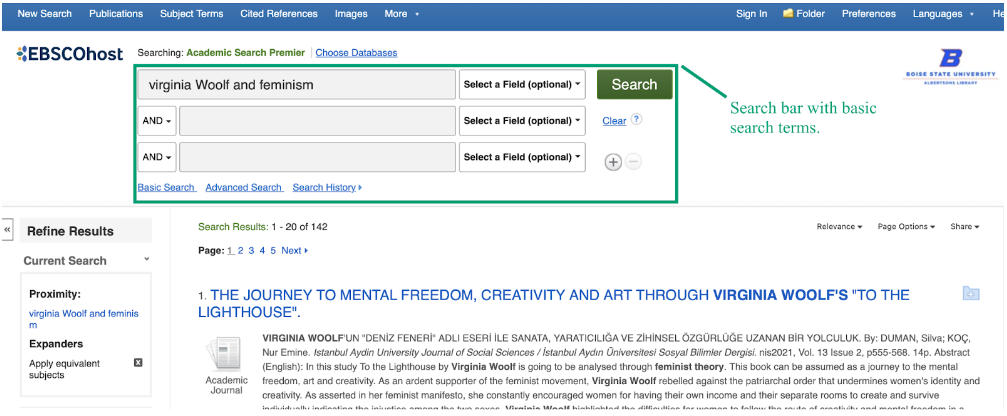

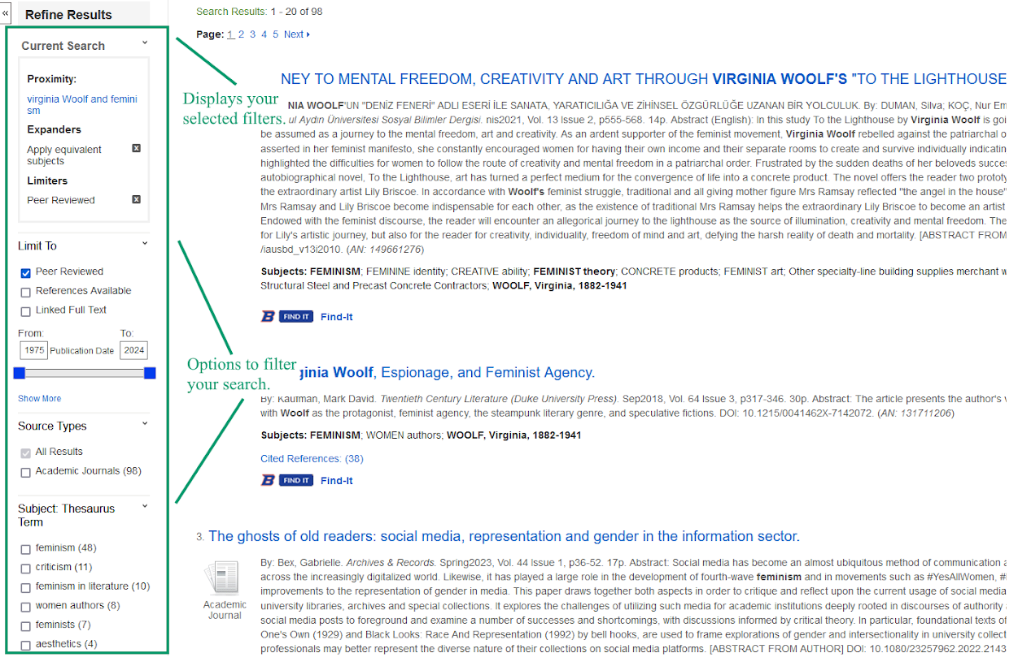

- Write the slide titles to match your talk outline. These should be clear and informative declarative sentences that succinctly give the main idea of the slide (e.g., don’t use “Methods” as a slide title). Have one major idea per slide. In a YouTube talk on designing effective slides , researcher Michael Alley shows examples of instructive slide titles.

- Decide how you will convey the main idea of the slide (e.g., what figures, photographs, equations, statistics, references, or other elements you will need). The body of the slide should support the slide’s main idea.

- Under each slide title, outline what you want to say, in bullet points.

In sum, for each slide, prepare a title that summarizes its major idea, a list of visual elements, and a summary of the points you will make. Ensure each slide connects to your thesis. If it doesn’t, then you don’t need the slide.

Slides for scientific presentations have three major components: text (including labels and legends), graphics, and equations. Here, we give tips on how to present each of these components.

- Have an informative title slide. Include the names of all coauthors and their affiliations. Include an attractive image relating to your study.

- Make the foreground content of your slides “pop” by using an appropriate background. Slides that have white backgrounds with black text work well for small rooms, whereas slides with black backgrounds and white text are suitable for large rooms.

- The layout of your slides should be simple. Pay attention to how and where you lay the visual and text elements on each slide. It’s tempting to cram information, but you need lots of empty space. Retain space at the sides and bottom of your slides.

- Use sans serif fonts with a font size of at least 20 for text, and up to 40 for slide titles. Citations can be in 14 font and should be included at the bottom of the slide.

- Use bold or italics to emphasize words, not underlines or caps. Keep these effects to a minimum.

- Use concise text . You don’t need full sentences. Convey the essence of your message in as few words as possible. Write down what you’d like to say, and then shorten it for the slide. Remove unnecessary filler words.

- Text blocks should be limited to two lines. This will prevent you from crowding too much information on the slide.

- Include names of technical terms in your talk slides, especially if they are not familiar to everyone in the audience.

- Proofread your slides. Typos and grammatical errors are distracting for your audience.

- Include citations for the hypotheses or observations of other scientists.

- Good figures and graphics are essential to sustain audience interest. Use graphics and photographs to show the experiment or study system in action and to explain abstract concepts.

- Don’t use figures straight from your paper as they may be too detailed for your talk, and details like axes may be too small. Make new versions if necessary. Make them large enough to be visible from the back of the room.

- Use graphs to show your results, not tables. Tables are difficult for your audience to digest! If you must present a table, keep it simple.

- Label the axes of graphs and indicate the units. Label important components of graphics and photographs and include captions. Include sources for graphics that are not your own.

- Explain all the elements of a graph. This includes the axes, what the colors and markers mean, and patterns in the data.

- Use colors in figures and text in a meaningful, not random, way. For example, contrasting colors can be effective for pointing out comparisons and/or differences. Don’t use neon colors or pastels.

- Use thick lines in figures, and use color to create contrasts in the figures you present. Don’t use red/green or red/blue combinations, as color-blind audience members can’t distinguish between them.

- Arrows or circles can be effective for drawing attention to key details in graphs and equations. Add some text annotations along with them.

- Write your summary and conclusion slides using graphics, rather than showing a slide with a list of bullet points. Showing some of your results again can be helpful to remind the audience of your message.

- If your talk has equations, take time to explain them. Include text boxes to explain variables and mathematical terms, and put them under each term in the equation.

- Combine equations with a graphic that shows the scientific principle, or include a diagram of the mathematical model.

- Use animations judiciously. They are helpful to reveal complex ideas gradually, for example, if you need to make a comparison or contrast or to build a complicated argument or figure. For lists, reveal one bullet point at a time. New ideas appearing sequentially will help your audience follow your logic.

- Slide transitions should be simple. Silly ones distract from your message.

- Decide how you will make the transition as you move from one section of your talk to the next. For example, if you spend time talking through details, provide a summary afterward, especially in a long talk. Another common tactic is to have a “home slide” that you return to multiple times during the talk that reinforces your main idea or message. In her YouTube talk on designing effective scientific presentations , Stanford biologist Susan McConnell suggests using the approach of home slides to build a cohesive narrative.

To deliver a polished presentation, it is essential to practice it. Here are some tips.

- For your first run-through, practice alone. Pay attention to your narrative. Does your story flow naturally? Do you know how you will start and end? Are there any awkward transitions? Do animations help you tell your story? Do your slides help to convey what you are saying or are they missing components?

- Next, practice in front of your advisor, and/or your peers (e.g., your lab group). Ask someone to time your talk. Take note of their feedback and the questions that they ask you (you might be asked similar questions during your real talk).

- Edit your talk, taking into account the feedback you’ve received. Eliminate superfluous slides that don’t contribute to your takeaway message.

- Practice as many times as needed to memorize the order of your slides and the key transition points of your talk. However, don’t try to learn your talk word for word. Instead, memorize opening and closing statements, and sentences at key junctures in the presentation. Your presentation should resemble a serious but spontaneous conversation with the audience.

- Practicing multiple times also helps you hone the delivery of your talk. While rehearsing, pay attention to your vocal intonations and speed. Make sure to take pauses while you speak, and make eye contact with your imaginary audience.

- Make sure your talk finishes within the allotted time, and remember to leave time for questions. Conferences are particularly strict on run time.

- Anticipate questions and challenges from the audience, and clarify ambiguities within your slides and/or speech in response.

- If you anticipate that you could be asked questions about details but you don’t have time to include them, or they detract from the main message of your talk, you can prepare slides that address these questions and place them after the final slide of your talk.

➡️ More tips for giving scientific presentations

An organized presentation with a clear narrative will help you communicate your ideas effectively, which is essential for engaging your audience and conveying the importance of your work. Taking time to plan and outline your scientific presentation before writing the slides will help you manage your nerves and feel more confident during the presentation, which will improve your overall performance.

A good scientific presentation has an engaging scientific narrative with a memorable take-home message. It has clear, informative slides that enhance what the speaker says. You need to practice your talk many times to ensure you deliver a polished presentation.

First, consider who will attend your presentation, and what you want the audience to learn about your research. Tailor your content to their level of knowledge and interests. Second, create an outline for your presentation, including the key points you want to make and the evidence you will use to support those points. Finally, practice your presentation several times to ensure that it flows smoothly and that you are comfortable with the material.

Prepare an opening that immediately gets the audience’s attention. A common device is a why or a how question, or a statement of a major open problem in your field, but you could also start with a quote, interesting statistic, or case study from your field.

Scientific presentations typically either focus on a single study (e.g., a 15-minute conference presentation) or tell the story of multiple studies (e.g., a PhD defense or 50-minute conference keynote talk). For a single study talk, the structure follows the scientific paper format: Introduction, Methods, Results, Summary, and Conclusion, whereas the format of a talk discussing multiple studies is more complex, but a theme unifies the studies.

Ensure you have one major idea per slide, and convey that idea clearly (through images, equations, statistics, citations, video, etc.). The slide should include a title that summarizes the major point of the slide, should not contain too much text or too many graphics, and color should be used meaningfully.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Biomedical Engineering and the Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, United States of America

- Kristen M. Naegle

Published: December 2, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

- Reader Comments

Citation: Naegle KM (2021) Ten simple rules for effective presentation slides. PLoS Comput Biol 17(12): e1009554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554

Copyright: © 2021 Kristen M. Naegle. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The author has declared no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The “presentation slide” is the building block of all academic presentations, whether they are journal clubs, thesis committee meetings, short conference talks, or hour-long seminars. A slide is a single page projected on a screen, usually built on the premise of a title, body, and figures or tables and includes both what is shown and what is spoken about that slide. Multiple slides are strung together to tell the larger story of the presentation. While there have been excellent 10 simple rules on giving entire presentations [ 1 , 2 ], there was an absence in the fine details of how to design a slide for optimal effect—such as the design elements that allow slides to convey meaningful information, to keep the audience engaged and informed, and to deliver the information intended and in the time frame allowed. As all research presentations seek to teach, effective slide design borrows from the same principles as effective teaching, including the consideration of cognitive processing your audience is relying on to organize, process, and retain information. This is written for anyone who needs to prepare slides from any length scale and for most purposes of conveying research to broad audiences. The rules are broken into 3 primary areas. Rules 1 to 5 are about optimizing the scope of each slide. Rules 6 to 8 are about principles around designing elements of the slide. Rules 9 to 10 are about preparing for your presentation, with the slides as the central focus of that preparation.

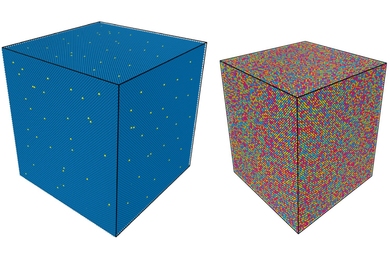

Rule 1: Include only one idea per slide

Each slide should have one central objective to deliver—the main idea or question [ 3 – 5 ]. Often, this means breaking complex ideas down into manageable pieces (see Fig 1 , where “background” information has been split into 2 key concepts). In another example, if you are presenting a complex computational approach in a large flow diagram, introduce it in smaller units, building it up until you finish with the entire diagram. The progressive buildup of complex information means that audiences are prepared to understand the whole picture, once you have dedicated time to each of the parts. You can accomplish the buildup of components in several ways—for example, using presentation software to cover/uncover information. Personally, I choose to create separate slides for each piece of information content I introduce—where the final slide has the entire diagram, and I use cropping or a cover on duplicated slides that come before to hide what I’m not yet ready to include. I use this method in order to ensure that each slide in my deck truly presents one specific idea (the new content) and the amount of the new information on that slide can be described in 1 minute (Rule 2), but it comes with the trade-off—a change to the format of one of the slides in the series often means changes to all slides.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Top left: A background slide that describes the background material on a project from my lab. The slide was created using a PowerPoint Design Template, which had to be modified to increase default text sizes for this figure (i.e., the default text sizes are even worse than shown here). Bottom row: The 2 new slides that break up the content into 2 explicit ideas about the background, using a central graphic. In the first slide, the graphic is an explicit example of the SH2 domain of PI3-kinase interacting with a phosphorylation site (Y754) on the PDGFR to describe the important details of what an SH2 domain and phosphotyrosine ligand are and how they interact. I use that same graphic in the second slide to generalize all binding events and include redundant text to drive home the central message (a lot of possible interactions might occur in the human proteome, more than we can currently measure). Top right highlights which rules were used to move from the original slide to the new slide. Specific changes as highlighted by Rule 7 include increasing contrast by changing the background color, increasing font size, changing to sans serif fonts, and removing all capital text and underlining (using bold to draw attention). PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009554.g001

Rule 2: Spend only 1 minute per slide

When you present your slide in the talk, it should take 1 minute or less to discuss. This rule is really helpful for planning purposes—a 20-minute presentation should have somewhere around 20 slides. Also, frequently giving your audience new information to feast on helps keep them engaged. During practice, if you find yourself spending more than a minute on a slide, there’s too much for that one slide—it’s time to break up the content into multiple slides or even remove information that is not wholly central to the story you are trying to tell. Reduce, reduce, reduce, until you get to a single message, clearly described, which takes less than 1 minute to present.

Rule 3: Make use of your heading

When each slide conveys only one message, use the heading of that slide to write exactly the message you are trying to deliver. Instead of titling the slide “Results,” try “CTNND1 is central to metastasis” or “False-positive rates are highly sample specific.” Use this landmark signpost to ensure that all the content on that slide is related exactly to the heading and only the heading. Think of the slide heading as the introductory or concluding sentence of a paragraph and the slide content the rest of the paragraph that supports the main point of the paragraph. An audience member should be able to follow along with you in the “paragraph” and come to the same conclusion sentence as your header at the end of the slide.

Rule 4: Include only essential points

While you are speaking, audience members’ eyes and minds will be wandering over your slide. If you have a comment, detail, or figure on a slide, have a plan to explicitly identify and talk about it. If you don’t think it’s important enough to spend time on, then don’t have it on your slide. This is especially important when faculty are present. I often tell students that thesis committee members are like cats: If you put a shiny bauble in front of them, they’ll go after it. Be sure to only put the shiny baubles on slides that you want them to focus on. Putting together a thesis meeting for only faculty is really an exercise in herding cats (if you have cats, you know this is no easy feat). Clear and concise slide design will go a long way in helping you corral those easily distracted faculty members.

Rule 5: Give credit, where credit is due

An exception to Rule 4 is to include proper citations or references to work on your slide. When adding citations, names of other researchers, or other types of credit, use a consistent style and method for adding this information to your slides. Your audience will then be able to easily partition this information from the other content. A common mistake people make is to think “I’ll add that reference later,” but I highly recommend you put the proper reference on the slide at the time you make it, before you forget where it came from. Finally, in certain kinds of presentations, credits can make it clear who did the work. For the faculty members heading labs, it is an effective way to connect your audience with the personnel in the lab who did the work, which is a great career booster for that person. For graduate students, it is an effective way to delineate your contribution to the work, especially in meetings where the goal is to establish your credentials for meeting the rigors of a PhD checkpoint.

Rule 6: Use graphics effectively

As a rule, you should almost never have slides that only contain text. Build your slides around good visualizations. It is a visual presentation after all, and as they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. However, on the flip side, don’t muddy the point of the slide by putting too many complex graphics on a single slide. A multipanel figure that you might include in a manuscript should often be broken into 1 panel per slide (see Rule 1 ). One way to ensure that you use the graphics effectively is to make a point to introduce the figure and its elements to the audience verbally, especially for data figures. For example, you might say the following: “This graph here shows the measured false-positive rate for an experiment and each point is a replicate of the experiment, the graph demonstrates …” If you have put too much on one slide to present in 1 minute (see Rule 2 ), then the complexity or number of the visualizations is too much for just one slide.

Rule 7: Design to avoid cognitive overload

The type of slide elements, the number of them, and how you present them all impact the ability for the audience to intake, organize, and remember the content. For example, a frequent mistake in slide design is to include full sentences, but reading and verbal processing use the same cognitive channels—therefore, an audience member can either read the slide, listen to you, or do some part of both (each poorly), as a result of cognitive overload [ 4 ]. The visual channel is separate, allowing images/videos to be processed with auditory information without cognitive overload [ 6 ] (Rule 6). As presentations are an exercise in listening, and not reading, do what you can to optimize the ability of the audience to listen. Use words sparingly as “guide posts” to you and the audience about major points of the slide. In fact, you can add short text fragments, redundant with the verbal component of the presentation, which has been shown to improve retention [ 7 ] (see Fig 1 for an example of redundant text that avoids cognitive overload). Be careful in the selection of a slide template to minimize accidentally adding elements that the audience must process, but are unimportant. David JP Phillips argues (and effectively demonstrates in his TEDx talk [ 5 ]) that the human brain can easily interpret 6 elements and more than that requires a 500% increase in human cognition load—so keep the total number of elements on the slide to 6 or less. Finally, in addition to the use of short text, white space, and the effective use of graphics/images, you can improve ease of cognitive processing further by considering color choices and font type and size. Here are a few suggestions for improving the experience for your audience, highlighting the importance of these elements for some specific groups:

- Use high contrast colors and simple backgrounds with low to no color—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment.

- Use sans serif fonts and large font sizes (including figure legends), avoid italics, underlining (use bold font instead for emphasis), and all capital letters—for persons with dyslexia or visual impairment [ 8 ].

- Use color combinations and palettes that can be understood by those with different forms of color blindness [ 9 ]. There are excellent tools available to identify colors to use and ways to simulate your presentation or figures as they might be seen by a person with color blindness (easily found by a web search).

- In this increasing world of virtual presentation tools, consider practicing your talk with a closed captioning system capture your words. Use this to identify how to improve your speaking pace, volume, and annunciation to improve understanding by all members of your audience, but especially those with a hearing impairment.

Rule 8: Design the slide so that a distracted person gets the main takeaway

It is very difficult to stay focused on a presentation, especially if it is long or if it is part of a longer series of talks at a conference. Audience members may get distracted by an important email, or they may start dreaming of lunch. So, it’s important to look at your slide and ask “If they heard nothing I said, will they understand the key concept of this slide?” The other rules are set up to help with this, including clarity of the single point of the slide (Rule 1), titling it with a major conclusion (Rule 3), and the use of figures (Rule 6) and short text redundant to your verbal description (Rule 7). However, with each slide, step back and ask whether its main conclusion is conveyed, even if someone didn’t hear your accompanying dialog. Importantly, ask if the information on the slide is at the right level of abstraction. For example, do you have too many details about the experiment, which hides the conclusion of the experiment (i.e., breaking Rule 1)? If you are worried about not having enough details, keep a slide at the end of your slide deck (after your conclusions and acknowledgments) with the more detailed information that you can refer to during a question and answer period.

Rule 9: Iteratively improve slide design through practice

Well-designed slides that follow the first 8 rules are intended to help you deliver the message you intend and in the amount of time you intend to deliver it in. The best way to ensure that you nailed slide design for your presentation is to practice, typically a lot. The most important aspects of practicing a new presentation, with an eye toward slide design, are the following 2 key points: (1) practice to ensure that you hit, each time through, the most important points (for example, the text guide posts you left yourself and the title of the slide); and (2) practice to ensure that as you conclude the end of one slide, it leads directly to the next slide. Slide transitions, what you say as you end one slide and begin the next, are important to keeping the flow of the “story.” Practice is when I discover that the order of my presentation is poor or that I left myself too few guideposts to remember what was coming next. Additionally, during practice, the most frequent things I have to improve relate to Rule 2 (the slide takes too long to present, usually because I broke Rule 1, and I’m delivering too much information for one slide), Rule 4 (I have a nonessential detail on the slide), and Rule 5 (I forgot to give a key reference). The very best type of practice is in front of an audience (for example, your lab or peers), where, with fresh perspectives, they can help you identify places for improving slide content, design, and connections across the entirety of your talk.

Rule 10: Design to mitigate the impact of technical disasters

The real presentation almost never goes as we planned in our heads or during our practice. Maybe the speaker before you went over time and now you need to adjust. Maybe the computer the organizer is having you use won’t show your video. Maybe your internet is poor on the day you are giving a virtual presentation at a conference. Technical problems are routinely part of the practice of sharing your work through presentations. Hence, you can design your slides to limit the impact certain kinds of technical disasters create and also prepare alternate approaches. Here are just a few examples of the preparation you can do that will take you a long way toward avoiding a complete fiasco:

- Save your presentation as a PDF—if the version of Keynote or PowerPoint on a host computer cause issues, you still have a functional copy that has a higher guarantee of compatibility.

- In using videos, create a backup slide with screen shots of key results. For example, if I have a video of cell migration, I’ll be sure to have a copy of the start and end of the video, in case the video doesn’t play. Even if the video worked, you can pause on this backup slide and take the time to highlight the key results in words if someone could not see or understand the video.

- Avoid animations, such as figures or text that flash/fly-in/etc. Surveys suggest that no one likes movement in presentations [ 3 , 4 ]. There is likely a cognitive underpinning to the almost universal distaste of pointless animations that relates to the idea proposed by Kosslyn and colleagues that animations are salient perceptual units that captures direct attention [ 4 ]. Although perceptual salience can be used to draw attention to and improve retention of specific points, if you use this approach for unnecessary/unimportant things (like animation of your bullet point text, fly-ins of figures, etc.), then you will distract your audience from the important content. Finally, animations cause additional processing burdens for people with visual impairments [ 10 ] and create opportunities for technical disasters if the software on the host system is not compatible with your planned animation.

Conclusions

These rules are just a start in creating more engaging presentations that increase audience retention of your material. However, there are wonderful resources on continuing on the journey of becoming an amazing public speaker, which includes understanding the psychology and neuroscience behind human perception and learning. For example, as highlighted in Rule 7, David JP Phillips has a wonderful TEDx talk on the subject [ 5 ], and “PowerPoint presentation flaws and failures: A psychological analysis,” by Kosslyn and colleagues is deeply detailed about a number of aspects of human cognition and presentation style [ 4 ]. There are many books on the topic, including the popular “Presentation Zen” by Garr Reynolds [ 11 ]. Finally, although briefly touched on here, the visualization of data is an entire topic of its own that is worth perfecting for both written and oral presentations of work, with fantastic resources like Edward Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” [ 12 ] or the article “Visualization of Biomedical Data” by O’Donoghue and colleagues [ 13 ].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the countless presenters, colleagues, students, and mentors from which I have learned a great deal from on effective presentations. Also, a thank you to the wonderful resources published by organizations on how to increase inclusivity. A special thanks to Dr. Jason Papin and Dr. Michael Guertin on early feedback of this editorial.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Teaching VUC for Making Better PowerPoint Presentations. n.d. Available from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/making-better-powerpoint-presentations/#baddeley .

- 8. Creating a dyslexia friendly workplace. Dyslexia friendly style guide. nd. Available from: https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-style-guide .

- 9. Cravit R. How to Use Color Blind Friendly Palettes to Make Your Charts Accessible. 2019. Available from: https://venngage.com/blog/color-blind-friendly-palette/ .

- 10. Making your conference presentation more accessible to blind and partially sighted people. n.d. Available from: https://vocaleyes.co.uk/services/resources/guidelines-for-making-your-conference-presentation-more-accessible-to-blind-and-partially-sighted-people/ .

- 11. Reynolds G. Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery. 2nd ed. New Riders Pub; 2011.

- 12. Tufte ER. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. 2nd ed. Graphics Press; 2001.

This page has been archived and is no longer being updated regularly.

Presenting your research effectively

Here's how to home in on your key message and present it in a clear, engaging way.

By Richard Chambers

Print version: page 28

For many graduate students, presenting their research is a daunting task. How do you cram your months' worth of data collection and analysis into a 10- to 20-minute presentation? Deciding what information to include and how to organize it can be more stressful than actually giving the presentation.

But anyone filled with presentation anxiety should remember that the difficult part is already over once it comes time to present. No one knows your research better than you, and those who come to listen to your presentation are probably there because they are interested in your research, not because they are required to be there. Taking this perspective can make presenting your research much less stressful because the focus of the task is no longer to engage an uninterested audience: It is to keep an already interested audience engaged.

Here are some suggestions for constructing a presentation using various multimedia tools, such as PowerPoint, Keynote and Prezi.

Planning: What should be included?

First, it is always important to refer to the APA Publication Manual as well as to your specific conference's guidelines. Second, before you start building any presentation, consider your audience. Will it be scientists who are familiar with your research area or will it be people who may never have had a class in psychology? Based on the answer, you will want to make sure you structure your presentation with the appropriate depth and terminology.

Determining the main messages you want to communicate in your presentation is often the next step in organizing your thoughts. As you create your presentation, sometimes it is difficult to determine whether a particular piece of information is important or necessary. Consider the value added by each piece of content as you determine whether to include it or not. Often, the background and theory for your research must be presented concisely so that you have time to present your study and findings. Ten minutes is not much time, so emphasize the main points so that your audience has a clear understanding of your take-home messages. When you start planning, writing out content on individual Post-it Notes can be a great way to visually organize your thoughts and, ultimately, your presentation.

Building slides: The do's and don'ts

After you've decided on your content, the real fun begins: designing slides. There are no rules for how to build a slide, but here are a few suggestions to keep in mind:

Tell your story simply

Remember that you want to tell a story, not lecture people. The oral presentation as a whole should be the work of art, and the slides should be supplementary to the story you are trying to convey. When laying out content and designing slides, remember that less is more. Having more slides with less content on each will help keep your audience focused more on what you are saying and prevent them from staring blankly at your slides.

Consider the billboard

Marketers try to use only three seconds' worth of content, the same amount of time a driver has to view a billboard. Your audience may not be driving cars, but you want them to stay engaged with your story, and this makes the three-seconds rule a good one to apply when building a slide. If it takes more than three seconds to read the slide, consider revising it.

Keep it clean

White space will help the slide appear cleaner and more aesthetically appealing. It is important to note that white space may not always be white. Each presentation should have its own color palette that consists of approximately three complementary colors. Try not to use more than three colors, and be aware of the emotion certain colors may evoke. For example, blue is the color of the sky and the ocean and is typically a soothing and relaxing color; red, on the other hand, is a bold, passionate color that may evoke more aggressive feelings.

Don't get too lively

Animation is another customizable option of presentations, but it may not be worth the effort. Animation can be distracting, making it difficult for the audience to stay with the story being told. When in doubt about animation, remember to ask what value is being added. There may be times when you really want to add emphasis to a specific word or phrase. If this is the case, and you deem it necessary, animation may be an acceptable choice. For example, the "grow" feature may be useful for adding emphasis to a word or phrase.

It is important to have highly readable slides with good contrast between the words and background. Choose a font that is easy to read, and be aware that each font has a different personality and sends a different message. The personality of some fonts may even be considered inappropriate for certain settings. For example, the font Comic Sans is a "lighter" font and would most likely not be a wise choice for a presentation at a conference.

Other important considerations include typesetting and the spacing of letters, words and lines. These all affect readability but can also be used as a way to add emphasis. Sometimes you may feel a need to use bullet points. Do not. Typesetting can replace bullet points and add extra distinction to each line of content without cluttering the slide with bullets. For example, consider bolding and increasing the font size of parent lines and indenting child lines.

If you find that your slides contain mainly words, remember that a picture, chart or diagram can augment the text. People often depend on vision as their primary sense; this means your audience has a potential preference for visual information other than just words on the screen.

Presenting data: Think about what kind of graph is best

When you share information, specifically about data, bar graphs should usually be your first choice, with scatter plots a close second because they are simple. The same suggestion about having more slides with less content on each applies to charts and graphs. If the graph or chart will look cleaner as two graphs instead of one, use two graphs.

Accuracy of a graph is, of course, important. For example, it is easy to convey the wrong message simply by altering the range of the y-axis. A restricted y-axis can make the differences between groups look much larger than they actually are to those audience members who do not look closely. It is always important to be ethical and to ensure that information, especially about data, is not being misrepresented. Strive to make charts and graphs easily interpretable, and try not to clutter them with additional numbers.

Building presentations does not need to be a challenge. Presenting should be an opportunity to share with others something very important to you — your research. These suggestions can be used as a starting point to guide the development of future research presentations and to help relieve some of the stress surrounding them.

Richard Chambers is the industrial/organizational psychology representative on the APA Student Science Council. He is a doctoral student at Louisiana Tech University.

Letters to the Editor

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

- Presenting the Research Paper

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Writing the Research Paper

Writing an Abstract

Oral presentation, compiling a powerpoint.

Abstract : a short statement that describes a longer work.

- Indicate the subject.

- Describe the purpose of the investigation.

- Briefly discuss the method used.

- Make a statement about the result.

Oral presentations usually introduce a discussion of a topic or research paper. A good oral presentation is focused, concise, and interesting in order to trigger a discussion.

- Be well prepared; write a detailed outline.

- Introduce the subject.

- Talk about the sources and the method.

- Indicate if there are conflicting views about the subject (conflicting views trigger discussion).

- Make a statement about your new results (if this is your research paper).

- Use visual aids or handouts if appropriate.

An effective PowerPoint presentation is just an aid to the presentation, not the presentation itself .

- Be brief and concise.

- Focus on the subject.

- Attract attention; indicate interesting details.

- If possible, use relevant visual illustrations (pictures, maps, charts graphs, etc.).

- Use bullet points or numbers to structure the text.

- Make clear statements about the essence/results of the topic/research.

- Don't write down the whole outline of your paper and nothing else.

- Don't write long full sentences on the slides.

- Don't use distracting colors, patterns, pictures, decorations on the slides.

- Don't use too complicated charts, graphs; only those that are relatively easy to understand.

- << Previous: Writing the Research Paper

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

- Chapter Seven: Presenting Your Results

This chapter serves as the culmination of the previous chapters, in that it focuses on how to present the results of one's study, regardless of the choice made among the three methods. Writing in academics has a form and style that you will want to apply not only to report your own research, but also to enhance your skills at reading original research published in academic journals. Beyond the basic academic style of report writing, there are specific, often unwritten assumptions about how quantitative, qualitative, and critical/rhetorical studies should be organized and the information they should contain. This chapter discusses how to present your results in writing, how to write accessibly, how to visualize data, and how to present your results in person.

- Chapter One: Introduction

- Chapter Two: Understanding the distinctions among research methods

- Chapter Three: Ethical research, writing, and creative work

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 2 - Doing Your Study)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 3 - Making Sense of Your Study)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Data (Part 2)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 2)

Written Presentation of Results

Once you've gone through the process of doing communication research – using a quantitative, qualitative, or critical/rhetorical methodological approach – the final step is to communicate it.

The major style manuals (the APA Manual, the MLA Handbook, and Turabian) are very helpful in documenting the structure of writing a study, and are highly recommended for consultation. But, no matter what style manual you may use, there are some common elements to the structure of an academic communication research paper.

Title Page :

This is simple: Your Paper's Title, Your Name, Your Institutional Affiliation (e.g., University), and the Date, each on separate lines, centered on the page. Try to make your title both descriptive (i.e., it gives the reader an idea what the study is about) and interesting (i.e., it is catchy enough to get one's attention).

For example, the title, "The uncritical idealization of a compensated psychopath character in a popular book series," would not be an inaccurate title for a published study, but it is rather vague and exceedingly boring. That study's author fortunately chose the title, "A boyfriend to die for: Edward Cullen as compensated psychopath in Stephanie Meyer's Twilight ," which is more precisely descriptive, and much more interesting (Merskin, 2011). The use of the colon in academic titles can help authors accomplish both objectives: a catchy but relevant phrase, followed by a more clear explanation of the article's topic.

In some instances, you might be asked to write an abstract, which is a summary of your paper that can range in length from 75 to 250 words. If it is a published paper, it is useful to include key search terms in this brief description of the paper (the title may already have a few of these terms as well). Although this may be the last thing your write, make it one of the best things you write, because this may be the first thing your audience reads about the paper (and may be the only thing read if it is written badly). Summarize the problem/research question, your methodological approach, your results and conclusions, and the significance of the paper in the abstract.

Quantitative and qualitative studies will most typically use the rest of the section titles noted below. Critical/rhetorical studies will include many of the same steps, but will often have different headings. For example, a critical/rhetorical paper will have an introduction, definition of terms, and literature review, followed by an analysis (often divided into sections by areas of investigation) and ending with a conclusion/implications section. Because critical/rhetorical research is much more descriptive, the subheadings in such a paper are often times not generic subheads like "literature review," but instead descriptive subheadings that apply to the topic at hand, as seen in the schematic below. Because many journals expect the article to follow typical research paper headings of introduction, literature review, methods, results, and discussion, we discuss these sections briefly next.

Introduction:

As you read social scientific journals (see chapter 1 for examples), you will find that they tend to get into the research question quickly and succinctly. Journal articles from the humanities tradition tend to be more descriptive in the introduction. But, in either case, it is good to begin with some kind of brief anecdote that gets the reader engaged in your work and lets the reader understand why this is an interesting topic. From that point, state your research question, define the problem (see Chapter One) with an overview of what we do and don't know, and finally state what you will do, or what you want to find out. The introduction thus builds the case for your topic, and is the beginning of building your argument, as we noted in chapter 1.

By the end of the Introduction, the reader should know what your topic is, why it is a significant communication topic, and why it is necessary that you investigate it (e.g., it could be there is gap in literature, you will conduct valuable exploratory research, or you will provide a new model for solving some professional or social problem).

Literature Review:

The literature review summarizes and organizes the relevant books, articles, and other research in this area. It sets up both quantitative and qualitative studies, showing the need for the study. For critical/rhetorical research, the literature review often incorporates the description of the historical context and heuristic vocabulary, with key terms defined in this section of the paper. For more detail on writing a literature review, see Appendix 1.

The methods of your paper are the processes that govern your research, where the researcher explains what s/he did to solve the problem. As you have seen throughout this book, in communication studies, there are a number of different types of research methods. For example, in quantitative research, one might conduct surveys, experiments, or content analysis. In qualitative research, one might instead use interviews and observations. Critical/rhetorical studies methods are more about the interpretation of texts or the study of popular culture as communication. In creative communication research, the method may be an interpretive performance studies or filmmaking. Other methods used sometimes alone, or in combination with other methods, include legal research, historical research, and political economy research.

In quantitative and qualitative research papers, the methods will be most likely described according to the APA manual standards. At the very least, the methods will include a description of participants, data collection, and data analysis, with specific details on each of these elements. For example, in an experiment, the researcher will describe the number of participants, the materials used, the design of the experiment, the procedure of the experiment, and what statistics will be used to address the hypotheses/research questions.

Critical/rhetorical researchers rarely have a specific section called "methods," as opposed to quantitative and qualitative researchers, but rather demonstrate the method they use for analysis throughout the writing of their piece.

Helping your reader understand the methods you used for your study is important not only for your own study's credibility, but also for possible replication of your study by other researchers. A good guideline to keep in mind is transparency . You want to be as clear as possible in describing the decisions you made in designing your study, gathering and analyzing your data so that the reader can retrace your steps and understand how you came to the conclusions you formed. A research study can be very good, but if it is not clearly described so that others can see how the results were determined or obtained, then the quality of the study and its potential contributions are lost.

After you completed your study, your findings will be listed in the results section. Particularly in a quantitative study, the results section is for revisiting your hypotheses and reporting whether or not your results supported them, and the statistical significance of the results. Whether your study supported or contradicted your hypotheses, it's always helpful to fully report what your results were. The researcher usually organizes the results of his/her results section by research question or hypothesis, stating the results for each one, using statistics to show how the research question or hypothesis was answered in the study.

The qualitative results section also may be organized by research question, but usually is organized by themes which emerged from the data collected. The researcher provides rich details from her/his observations and interviews, with detailed quotations provided to illustrate the themes identified. Sometimes the results section is combined with the discussion section.

Critical/rhetorical researchers would include their analysis often with different subheadings in what would be considered a "results" section, yet not labeled specifically this way.

Discussion:

In the discussion section, the researcher gives an appraisal of the results. Here is where the researcher considers the results, particularly in light of the literature review, and explains what the findings mean. If the results confirmed or corresponded with the findings of other literature, then that should be stated. If the results didn't support the findings of previous studies, then the researcher should develop an explanation of why the study turned out this way. Sometimes, this section is called a "conclusion" by researchers.

References:

In this section, all of the literature cited in the text should have full references in alphabetical order. Appendices: Appendix material includes items like questionnaires used in the study, photographs, documents, etc. An alphabetical letter is assigned for each piece (e.g. Appendix A, Appendix B), with a second line of title describing what the appendix contains (e.g. Participant Informed Consent, or New York Times Speech Coverage). They should be organized consistently with the order in which they are referenced in the text of the paper. The page numbers for appendices are consecutive with the paper and reference list.

Tables/Figures:

Tables and figures are referenced in the text, but included at the end of the study and numbered consecutively. (Check with your professor; some like to have tables and figures inserted within the paper's main text.) Tables generally are data in a table format, whereas figures are diagrams (such as a pie chart) and drawings (such as a flow chart).

Accessible Writing

As you may have noticed, academic writing does have a language (e.g., words like heuristic vocabulary and hypotheses) and style (e.g., literature reviews) all its own. It is important to engage in that language and style, and understand how to use it to communicate effectively in an academic context . Yet, it is also important to remember that your analyses and findings should also be written to be accessible. Writers should avoid excessive jargon, or—even worse—deploying jargon to mask an incomplete understanding of a topic.

The scourge of excessive jargon in academic writing was the target of a famous hoax in 1996. A New York University physics professor submitted an article, " Transgressing the Boundaries: Toward a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity ," to a special issue of the academic journal Social Text devoted to science and postmodernism. The article was designed to point out how dense academic jargon can sometimes mask sloppy thinking. As the professor, Alan Sokal, had expected, the article was published. One sample sentence from the article reads:

It has thus become increasingly apparent that physical "reality", no less than social "reality", is at bottom a social and linguistic construct; that scientific "knowledge", far from being objective, reflects and encodes the dominant ideologies and power relations of the culture that produced it; that the truth claims of science are inherently theory-laden and self-referential; and consequently, that the discourse of the scientific community, for all its undeniable value, cannot assert a privileged epistemological status with respect to counter-hegemonic narratives emanating from dissident or marginalized communities. (Sokal, 1996. pp. 217-218)

According to the journal's editor, about six reviewers had read the article but didn't suspect that it was phony. A public debate ensued after Sokal revealed his hoax. Sokal said he worried that jargon and intellectual fads cause academics to lose contact with the real world and "undermine the prospect for progressive social critique" ( Scott, 1996 ). The APA Manual recommends to avoid using technical vocabulary where it is not needed or relevant or if the technical language is overused, thus becoming jargon. In short, the APA argues that "scientific jargon...grates on the reader, encumbers the communication of information, and wastes space" (American Psychological Association, 2010, p. 68).

Data Visualization

Images and words have long existed on the printed page of manuscripts, yet, until recently, relatively few researchers possessed the resources to effectively combine images combined with words (Tufte, 1990, 1983). Communication scholars are only now becoming aware of this dimension in research as computer technologies have made it possible for many people to produce and publish multimedia presentations.

Although visuals may seem to be anathema to the primacy of the written word in research, they are a legitimate way, and at times the best way, to present ideas. Visual scholar Lester Faigley et al. (2004) explains how data visualizations have become part of our daily lives:

Visualizations can shed light on research as well. London-based David McCandless specializes in visualizing interesting research questions, or in his words "the questions I wanted answering" (2009, p. 7). His images include a graph of the peak times of the year for breakups (based on Facebook status updates), a radiation dosage chart , and some experiments with the Google Ngram Viewer , which charts the appearance of keywords in millions of books over hundreds of years.

The public domain image below creatively maps U.S. Census data of the outflow of people from California to other states between 1995 and 2000.

Visualizing one's research is possible in multiple ways. A simple technology, for example, is to enter data into a spreadsheet such as Excel, and select Charts or SmartArt to generate graphics. A number of free web tools can also transform raw data into useful charts and graphs. Many Eyes , an open source data visualization tool (sponsored by IBM Research), says its goal "is to 'democratize' visualization and to enable a new social kind of data analysis" (IBM, 2011). Another tool, Soundslides , enables users to import images and audio to create a photographic slideshow, while the program handles all of the background code. Other tools, often open source and free, can help visual academic research into interactive maps; interactive, image-based timelines; interactive charts; and simple 2-D and 3-D animations. Adobe Creative Suite (which includes popular software like Photoshop) is available on most computers at universities, but open source alternatives exist as well. Gimp is comparable to Photoshop, and it is free and relatively easy to use.

One online performance studies journal, Liminalities , is an excellent example of how "research" can be more than just printed words. In each issue, traditional academic essays and book reviews are often supported photographs, while other parts of an issue can include video, audio, and multimedia contributions. The journal, founded in 2005, treats performance itself as a methodology, and accepts contribution in html, mp3, Quicktime, and Flash formats.

For communication researchers, there is also a vast array of visual digital archives available online. Many of these archives are located at colleges and universities around the world, where digital librarians are spearheading a massive effort to make information—print, audio, visual, and graphic—available to the public as part of a global information commons. For example, the University of Iowa has a considerable digital archive including historical photos documenting American railroads and a database of images related to geoscience. The University of Northern Iowa has a growing Special Collections Unit that includes digital images of every UNI Yearbook between 1905 and 1923 and audio files of UNI jazz band performances. Researchers at he University of Michigan developed OAIster , a rich database that has joined thousands of digital archives in one searchable interface. Indeed, virtually every academic library is now digitizing all types of media, not just texts, and making them available for public viewing and, when possible, for use in presenting research. In addition to academic collections, the Library of Congress and the National Archives offer an ever-expanding range of downloadable media; commercial, user-generated databases such as Flickr, Buzznet, YouTube and Google Video offer a rich resource of images that are often free of copyright constraints (see Chapter 3 about Creative Commons licenses) and nonprofit endeavors, such as the Internet Archive , contain a formidable collection of moving images, still photographs, audio files (including concert recordings), and open source software.

Presenting your Work in Person

As Communication students, it's expected that you are not only able to communicate your research project in written form but also in person.

Before you do any oral presentation, it's good to have a brief "pitch" ready for anyone who asks you about your research. The pitch is routine in Hollywood: a screenwriter has just a few minutes to present an idea to a producer. Although your pitch will be more sophisticated than, say, " Snakes on a Plane " (which unfortunately was made into a movie), you should in just a few lines be able to explain the gist of your research to anyone who asks. Developing this concise description, you will have some practice in distilling what might be a complicated topic into one others can quickly grasp.

Oral presentation

In most oral presentations of research, whether at the end of a semester, or at a research symposium or conference, you will likely have just 10 to 20 minutes. This is probably not enough time to read the entire paper aloud, which is not what you should do anyway if you want people to really listen (although, unfortunately some make this mistake). Instead, the point of the presentation should be to present your research in an interesting manner so the listeners will want to read the whole thing. In the presentation, spend the least amount of time on the literature review (a very brief summary will suffice) and the most on your own original contribution. In fact, you may tell your audience that you are only presenting on one portion of the paper, and that you would be happy to talk more about your research and findings in the question and answer session that typically follows. Consider your presentation the beginning of a dialogue between you and the audience. Your tone shouldn't be "I have found everything important there is to find, and I will cram as much as I can into this presentation," but instead "I found some things you will find interesting, but I realize there is more to find."

Turabian (2007) has a helpful chapter on presenting research. Most important, she emphasizes, is to remember that your audience members are listeners, not readers. Thus, recall the lessons on speech making in your college oral communication class. Give an introduction, tell them what the problem is, and map out what you will present to them. Organize your findings into a few points, and don't get bogged down in minutiae. (The minutiae are for readers to find if they wish, not for listeners to struggle through.) PowerPoint slides are acceptable, but don't read them. Instead, create an outline of a few main points, and practice your presentation.

Turabian suggests an introduction of not more than three minutes, which should include these elements:

- The research topic you will address (not more than a minute).

- Your research question (30 seconds or less)

- An answer to "so what?" – explaining the relevance of your research (30 seconds)

- Your claim, or argument (30 seconds or less)

- The map of your presentation structure (30 seconds or less)

As Turabian (2007) suggests, "Rehearse your introduction, not only to get it right, but to be able to look your audience in the eye as you give it. You can look down at notes later" (p. 125).

Poster presentation

In some symposiums and conferences, you may be asked to present at a "poster" session. Instead of presenting on a panel of 4-5 people to an audience, a poster presenter is with others in a large hall or room, and talks one-on-one with visitors who look at the visual poster display of the research. As in an oral presentation, a poster highlights just the main point of the paper. Then, if visitors have questions, the author can informally discuss her/his findings.

To attract attention, poster presentations need to be nicely designed, or in the words of an advertising professor who schedules poster sessions at conferences, "be big, bold, and brief" ( Broyles , 2011). Large type (at least 18 pt.), graphics, tables, and photos are recommended.