- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

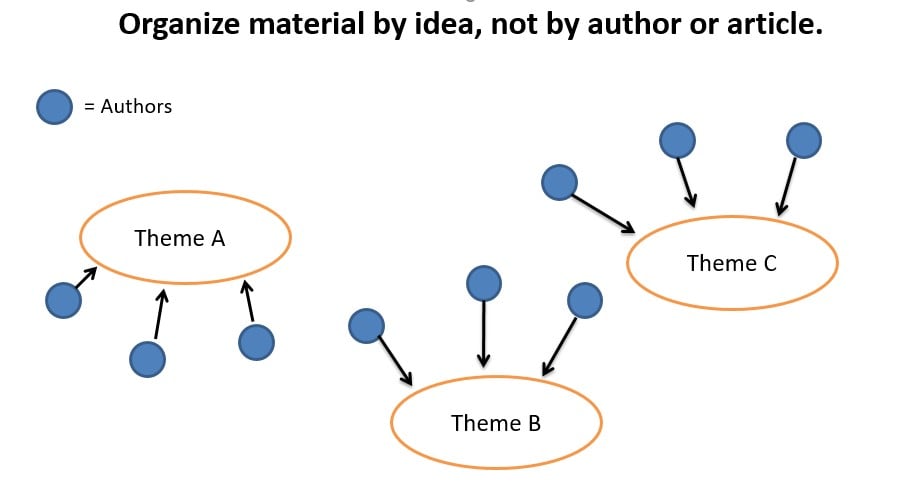

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

| What is synthesis? | What synthesis is NOT: |

|---|---|

Approaches to Synthesis

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2024 11:48 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Literature Syntheis 101

How To Synthesise The Existing Research (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | August 2023

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing a literature review is that they err on the side of describing the existing literature rather than providing a critical synthesis of it. In this post, we’ll unpack what exactly synthesis means and show you how to craft a strong literature synthesis using practical examples.

This post is based on our popular online course, Literature Review Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the full process of developing a literature review, step by step. If it’s your first time writing a literature review, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Literature Synthesis

- What exactly does “synthesis” mean?

- Aspect 1: Agreement

- Aspect 2: Disagreement

- Aspect 3: Key theories

- Aspect 4: Contexts

- Aspect 5: Methodologies

- Bringing it all together

What does “synthesis” actually mean?

As a starting point, let’s quickly define what exactly we mean when we use the term “synthesis” within the context of a literature review.

Simply put, literature synthesis means going beyond just describing what everyone has said and found. Instead, synthesis is about bringing together all the information from various sources to present a cohesive assessment of the current state of knowledge in relation to your study’s research aims and questions .

Put another way, a good synthesis tells the reader exactly where the current research is “at” in terms of the topic you’re interested in – specifically, what’s known , what’s not , and where there’s a need for more research .

So, how do you go about doing this?

Well, there’s no “one right way” when it comes to literature synthesis, but we’ve found that it’s particularly useful to ask yourself five key questions when you’re working on your literature review. Having done so, you can then address them more articulately within your actual write up. So, let’s take a look at each of these questions.

1. Points Of Agreement

The first question that you need to ask yourself is: “Overall, what things seem to be agreed upon by the vast majority of the literature?”

For example, if your research aim is to identify which factors contribute toward job satisfaction, you’ll need to identify which factors are broadly agreed upon and “settled” within the literature. Naturally, there may at times be some lone contrarian that has a radical viewpoint , but, provided that the vast majority of researchers are in agreement, you can put these random outliers to the side. That is, of course, unless your research aims to explore a contrarian viewpoint and there’s a clear justification for doing so.

Identifying what’s broadly agreed upon is an essential starting point for synthesising the literature, because you generally don’t want (or need) to reinvent the wheel or run down a road investigating something that is already well established . So, addressing this question first lays a foundation of “settled” knowledge.

Need a helping hand?

2. Points Of Disagreement

Related to the previous point, but on the other end of the spectrum, is the equally important question: “Where do the disagreements lie?” .

In other words, which things are not well agreed upon by current researchers? It’s important to clarify here that by disagreement, we don’t mean that researchers are (necessarily) fighting over it – just that there are relatively mixed findings within the empirical research , with no firm consensus amongst researchers.

This is a really important question to address as these “disagreements” will often set the stage for the research gap(s). In other words, they provide clues regarding potential opportunities for further research, which your study can then (hopefully) contribute toward filling. If you’re not familiar with the concept of a research gap, be sure to check out our explainer video covering exactly that .

3. Key Theories

The next question you need to ask yourself is: “Which key theories seem to be coming up repeatedly?” .

Within most research spaces, you’ll find that you keep running into a handful of key theories that are referred to over and over again. Apart from identifying these theories, you’ll also need to think about how they’re connected to each other. Specifically, you need to ask yourself:

- Are they all covering the same ground or do they have different focal points or underlying assumptions ?

- Do some of them feed into each other and if so, is there an opportunity to integrate them into a more cohesive theory?

- Do some of them pull in different directions ? If so, why might this be?

- Do all of the theories define the key concepts and variables in the same way, or is there some disconnect? If so, what’s the impact of this ?

Simply put, you’ll need to pay careful attention to the key theories in your research area, as they will need to feature within your theoretical framework , which will form a critical component within your final literature review. This will set the foundation for your entire study, so it’s essential that you be critical in this area of your literature synthesis.

If this sounds a bit fluffy, don’t worry. We deep dive into the theoretical framework (as well as the conceptual framework) and look at practical examples in Literature Review Bootcamp . If you’d like to learn more, take advantage of our limited-time offer to get 60% off the standard price.

4. Contexts

The next question that you need to address in your literature synthesis is an important one, and that is: “Which contexts have (and have not) been covered by the existing research?” .

For example, sticking with our earlier hypothetical topic (factors that impact job satisfaction), you may find that most of the research has focused on white-collar , management-level staff within a primarily Western context, but little has been done on blue-collar workers in an Eastern context. Given the significant socio-cultural differences between these two groups, this is an important observation, as it could present a contextual research gap .

In practical terms, this means that you’ll need to carefully assess the context of each piece of literature that you’re engaging with, especially the empirical research (i.e., studies that have collected and analysed real-world data). Ideally, you should keep notes regarding the context of each study in some sort of catalogue or sheet, so that you can easily make sense of this before you start the writing phase. If you’d like, our free literature catalogue worksheet is a great tool for this task.

5. Methodological Approaches

Last but certainly not least, you need to ask yourself the question: “What types of research methodologies have (and haven’t) been used?”

For example, you might find that most studies have approached the topic using qualitative methods such as interviews and thematic analysis. Alternatively, you might find that most studies have used quantitative methods such as online surveys and statistical analysis.

But why does this matter?

Well, it can run in one of two potential directions . If you find that the vast majority of studies use a specific methodological approach, this could provide you with a firm foundation on which to base your own study’s methodology . In other words, you can use the methodologies of similar studies to inform (and justify) your own study’s research design .

On the other hand, you might argue that the lack of diverse methodological approaches presents a research gap , and therefore your study could contribute toward filling that gap by taking a different approach. For example, taking a qualitative approach to a research area that is typically approached quantitatively. Of course, if you’re going to go against the methodological grain, you’ll need to provide a strong justification for why your proposed approach makes sense. Nevertheless, it is something worth at least considering.

Regardless of which route you opt for, you need to pay careful attention to the methodologies used in the relevant studies and provide at least some discussion about this in your write-up. Again, it’s useful to keep track of this on some sort of spreadsheet or catalogue as you digest each article, so consider grabbing a copy of our free literature catalogue if you don’t have anything in place.

Bringing It All Together

Alright, so we’ve looked at five important questions that you need to ask (and answer) to help you develop a strong synthesis within your literature review. To recap, these are:

- Which things are broadly agreed upon within the current research?

- Which things are the subject of disagreement (or at least, present mixed findings)?

- Which theories seem to be central to your research topic and how do they relate or compare to each other?

- Which contexts have (and haven’t) been covered?

- Which methodological approaches are most common?

Importantly, you’re not just asking yourself these questions for the sake of asking them – they’re not just a reflection exercise. You need to weave your answers to them into your actual literature review when you write it up. How exactly you do this will vary from project to project depending on the structure you opt for, but you’ll still need to address them within your literature review, whichever route you go.

The best approach is to spend some time actually writing out your answers to these questions, as opposed to just thinking about them in your head. Putting your thoughts onto paper really helps you flesh out your thinking . As you do this, don’t just write down the answers – instead, think about what they mean in terms of the research gap you’ll present , as well as the methodological approach you’ll take . Your literature synthesis needs to lay the groundwork for these two things, so it’s essential that you link all of it together in your mind, and of course, on paper.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

excellent , thank you

Thank you for this significant piece of information.

This piece of information is very helpful. Thank you so much and look forward to hearing more literature review from you in near the future.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

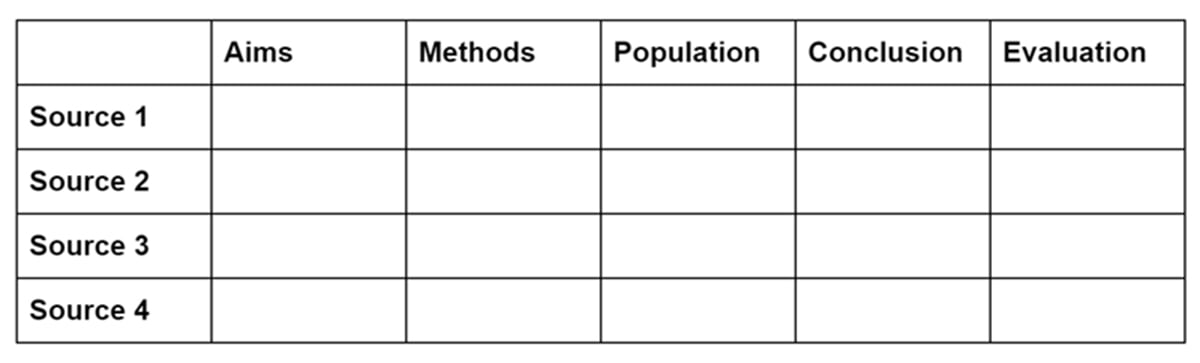

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

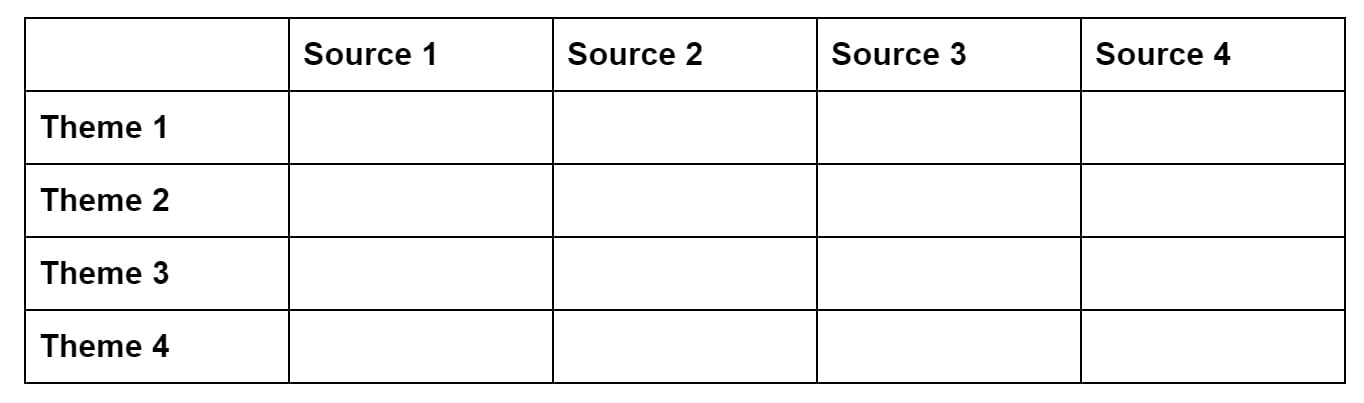

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 1:42 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

Library Guides

Literature reviews: synthesis.

- Criticality

Synthesise Information

So, how can you create paragraphs within your literature review that demonstrates your knowledge of the scholarship that has been done in your field of study?

You will need to present a synthesis of the texts you read.

Doug Specht, Senior Lecturer at the Westminster School of Media and Communication, explains synthesis for us in the following video:

Synthesising Texts

What is synthesis?

Synthesis is an important element of academic writing, demonstrating comprehension, analysis, evaluation and original creation.

With synthesis you extract content from different sources to create an original text. While paraphrase and summary maintain the structure of the given source(s), with synthesis you create a new structure.

The sources will provide different perspectives and evidence on a topic. They will be put together when agreeing, contrasted when disagreeing. The sources must be referenced.

Perfect your synthesis by showing the flow of your reasoning, expressing critical evaluation of the sources and drawing conclusions.

When you synthesise think of "using strategic thinking to resolve a problem requiring the integration of diverse pieces of information around a structuring theme" (Mateos and Sole 2009, p448).

Synthesis is a complex activity, which requires a high degree of comprehension and active engagement with the subject. As you progress in higher education, so increase the expectations on your abilities to synthesise.

How to synthesise in a literature review:

Identify themes/issues you'd like to discuss in the literature review. Think of an outline.

Read the literature and identify these themes/issues.

Critically analyse the texts asking: how does the text I'm reading relate to the other texts I've read on the same topic? Is it in agreement? Does it differ in its perspective? Is it stronger or weaker? How does it differ (could be scope, methods, year of publication etc.). Draw your conclusions on the state of the literature on the topic.

Start writing your literature review, structuring it according to the outline you planned.

Put together sources stating the same point; contrast sources presenting counter-arguments or different points.

Present your critical analysis.

Always provide the references.

The best synthesis requires a "recursive process" whereby you read the source texts, identify relevant parts, take notes, produce drafts, re-read the source texts, revise your text, re-write... (Mateos and Sole, 2009).

What is good synthesis?

The quality of your synthesis can be assessed considering the following (Mateos and Sole, 2009, p439):

Integration and connection of the information from the source texts around a structuring theme.

Selection of ideas necessary for producing the synthesis.

Appropriateness of the interpretation.

Elaboration of the content.

Example of Synthesis

Original texts (fictitious):

| Animal testing is necessary to save human lives. Incidents have happened where humans have died or have been seriously harmed for using drugs that had not been tested on animals (Smith 2008). | Animals feel pain in a way that is physiologically and neuroanatomically similar to humans (Chowdhury 2012). |

| Animal testing is not always used to assess the toxicology of a drug; sometimes painful experiments are undertaken to improve the effectiveness of cosmetics (Turner 2015) | Animals in distress can suffer psychologically, showing symptoms of depression and anxiety (Panatta and Hudson 2016). |

Synthesis:

Animal experimentation is a subject of heated debate. Some argue that painful experiments should be banned. Indeed it has been demonstrated that such experiments make animals suffer physically and psychologically (Chowdhury 2012; Panatta and Hudson 2016). On the other hand, it has been argued that animal experimentation can save human lives and reduce harm on humans (Smith 2008). This argument is only valid for toxicological testing, not for tests that, for example, merely improve the efficacy of a cosmetic (Turner 2015). It can be suggested that animal experimentation should be regulated to only allow toxicological risk assessment, and the suffering to the animals should be minimised.

Bibliography

Mateos, M. and Sole, I. (2009). Synthesising Information from various texts: A Study of Procedures and Products at Different Educational Levels. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24 (4), 435-451. Available from https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03178760 [Accessed 29 June 2021].

- << Previous: Structure

- Next: Criticality >>

- Last Updated: Nov 18, 2023 10:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/literature-reviews

CONNECT WITH US

Literature Review Basics

- What is a Literature Review?

- Synthesizing Research

- Using Research & Synthesis Tables

- Additional Resources

Synthesis: What is it?

First, let's be perfectly clear about what synthesizing your research isn't :

- - It isn't just summarizing the material you read

- - It isn't generating a collection of annotations or comments (like an annotated bibliography)

- - It isn't compiling a report on every single thing ever written in relation to your topic

When you synthesize your research, your job is to help your reader understand the current state of the conversation on your topic, relative to your research question. That may include doing the following:

- - Selecting and using representative work on the topic

- - Identifying and discussing trends in published data or results

- - Identifying and explaining the impact of common features (study populations, interventions, etc.) that appear frequently in the literature

- - Explaining controversies, disputes, or central issues in the literature that are relevant to your research question

- - Identifying gaps in the literature, where more research is needed

- - Establishing the discussion to which your own research contributes and demonstrating the value of your contribution

Essentially, you're telling your reader where they are (and where you are) in the scholarly conversation about your project.

Synthesis: How do I do it?

Synthesis, step by step.

This is what you need to do before you write your review.

- Identify and clearly describe your research question (you may find the Formulating PICOT Questions table at the Additional Resources tab helpful).

- Collect sources relevant to your research question.

- Organize and describe the sources you've found -- your job is to identify what types of sources you've collected (reviews, clinical trials, etc.), identify their purpose (what are they measuring, testing, or trying to discover?), determine the level of evidence they represent (see the Levels of Evidence table at the Additional Resources tab ), and briefly explain their major findings . Use a Research Table to document this step.

- Study the information you've put in your Research Table and examine your collected sources, looking for similarities and differences . Pay particular attention to populations , methods (especially relative to levels of evidence), and findings .

- Analyze what you learn in (4) using a tool like a Synthesis Table. Your goal is to identify relevant themes, trends, gaps, and issues in the research. Your literature review will collect the results of this analysis and explain them in relation to your research question.

Analysis tips

- - Sometimes, what you don't find in the literature is as important as what you do find -- look for questions that the existing research hasn't answered yet.

- - If any of the sources you've collected refer to or respond to each other, keep an eye on how they're related -- it may provide a clue as to whether or not study results have been successfully replicated.

- - Sorting your collected sources by level of evidence can provide valuable insight into how a particular topic has been covered, and it may help you to identify gaps worth addressing in your own work.

- << Previous: What is a Literature Review?

- Next: Using Research & Synthesis Tables >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 12:06 PM

- URL: https://usi.libguides.com/literature-review-basics

Literature Review How To

- Things To Consider

- Synthesizing Sources

- Video Tutorials

- Books On Literature Reviews

What is Synthesis

What is Synthesis? Synthesis writing is a form of analysis related to comparison and contrast, classification and division. On a basic level, synthesis requires the writer to pull together two or more summaries, looking for themes in each text. In synthesis, you search for the links between various materials in order to make your point. Most advanced academic writing, including literature reviews, relies heavily on synthesis. (Temple University Writing Center)

How To Synthesize Sources in a Literature Review

Literature reviews synthesize large amounts of information and present it in a coherent, organized fashion. In a literature review you will be combining material from several texts to create a new text – your literature review.

You will use common points among the sources you have gathered to help you synthesize the material. This will help ensure that your literature review is organized by subtopic, not by source. This means various authors' names can appear and reappear throughout the literature review, and each paragraph will mention several different authors.

When you shift from writing summaries of the content of a source to synthesizing content from sources, there is a number things you must keep in mind:

- Look for specific connections and or links between your sources and how those relate to your thesis or question.

- When writing and organizing your literature review be aware that your readers need to understand how and why the information from the different sources overlap.

- Organize your literature review by the themes you find within your sources or themes you have identified.

- << Previous: Things To Consider

- Next: Video Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Nov 30, 2018 4:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csun.edu/literature-review

Report ADA Problems with Library Services and Resources

Literature Reviews

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- Getting started

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

How to synthesize

Approaches to synthesis.

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

In the synthesis step of a literature review, researchers analyze and integrate information from selected sources to identify patterns and themes. This involves critically evaluating findings, recognizing commonalities, and constructing a cohesive narrative that contributes to the understanding of the research topic.

| Synthesis | Not synthesis |

|---|---|

| ✔️ Analyzing and integrating information | ❌ Simply summarizing individual studies or articles |

| ✔️ Identifying patterns and themes | ❌ Listing facts without interpretation |

| ✔️ Critically evaluating findings | ❌ Copy-pasting content from sources |

| ✔️ Constructing a cohesive narrative | ❌ Providing personal opinions |

| ✔️ Recognizing commonalities | ❌ Focusing only on isolated details |

| ✔️ Generating new perspectives | ❌ Repeating information verbatim |

Here are some examples of how to approach synthesizing the literature:

💡 By themes or concepts

🕘 Historically or chronologically

📊 By methodology

These organizational approaches can also be used when writing your review. It can be beneficial to begin organizing your references by these approaches in your citation manager by using folders, groups, or collections.

Create a synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix allows you to visually organize your literature.

Topic: ______________________________________________

| Source #2 | Source #3 | Source #4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Topic: Chemical exposure to workers in nail salons

| Gutierrez et al. 2015 | Hansen 2018 | Lee et al. 2014 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Participants reported multiple episodes of asthma over one year" (p. 58) | ||||

| "Nail salon workers who did not wear gloves routinely reported increased episodes of contact dermatitis" (p. 115) |

- << Previous: 4. Organize your results

- Next: 6. Write the review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 16, 2024 11:10 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

Literature Synthesis

- First Online: 31 August 2021

Cite this chapter

- Ana Paula Cardoso Ermel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3874-9792 5 ,

- D. P. Lacerda ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8011-3376 6 ,

- Maria Isabel W. M. Morandi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1337-1487 7 &

- Leandro Gauss ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5708-5912 8

1052 Accesses

1 Citations

- The original version of this chapter was revised: Figure 5.1 was moved to section 5.2.9. The correction to this chapter can be found at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75722-9_10

This chapter addresses the concept of Literature Synthesis and classifies it as Configurative and Aggregative based upon the research approach and objectives. For each type of synthesis, its main characteristics, techniques, and applications are pointed out.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Change history

06 february 2022.

In addition to the changes described above, we note that

Bacharach, S.B.: Organizational theories: some criteria for evaluation. Acad. Manag. Rev. Manag. 14 (4), 496–515. ISSN 1989.03637425

Google Scholar

Barnett-Page, E., Thomas, J.: Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 9 (1), 1–11 (2009). ISSN 1471-2288

Barry, M., Roux, L.: The case study method in examining land registration usage. Geomatica 67 (1), 9–20 (2013)

Article Google Scholar

Borenstein, M., et al.: Introduction to Meta-analysis, 421 p. Wiley, Padstow (2009). ISBN 978-0-470-05724-7

Borenstein, M.: Impact of Tamiflu on flu symptoms. (2021). Disponível em: www.Meta-Analysis.com . Acesso em: 3 fev 2021

Carroll, C., Booth, A., Cooper, K.: A worked example of “best fit” framework synthesis: A systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11 (2011)

Cruzes, D.S. et al.: Case studies synthesis: a thematic, cross-case, and narrative synthesis worked example. Empir. Softw. Eng. 20 (6), 1634–1665 (2015)

Dixon-Woods, M., et al.: Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 6 , 1–13 (2006)

Flemming, K.: Synthesis of quantitative and qualitative research: an example using critical interpretive synthesis. J. Adv. Nurs. 66 (1), 201–217 (2009)

France, E.F. et al.: A methodological systematic review of what’s wrong with meta-ethnography reporting. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14 (119), 1–16 (2014)

Gauss, L., Lacerda, D.P., Cauchick Miguel, P.A.: Module-based product family design: systematic literature review and meta-synthesis. J. Intell. Manuf. 32 (1), 265–312 (2021)

Gough, D., Oliver, S., Thomas, J.: An Introduction to Systematic Reviews, 1st edn, 288 p. SAGE Publications, Los Angeles (2012). ISBN 9781849201803

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank quarterly, 82 (4), 581–629. (2004). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

Higgins, J., Green, S.: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.

Higgins, J., Li, T., Deeks, J.J.: Analysing Data and Undertaking Meta-analyses. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.1. (2020a). Disponível em: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-10

Higgins, J., Li, T., Deeks, J.J.: Choosing Effect Measures and Computing Estimates of Effect. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.1. Cochrane (2020b). Disponível em: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Hopia, H., Latvala, E., Liimatainen, L.: Reviewing the methodology of an integrative review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 30 (4), 662–669 (2016)

Hull, S.: Doing Grounded Theory: Notes for the Aspiring Qualitative Analyst. Division of Geomatics, University of Cape Town (2013)

Kastner, M., et al.: Conceptual recommendations for selecting the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to answer research questions related to complex evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 73 (1), 1–21 (2016)

Koricheva, J., Gurevitch, J.: Place of Meta-analysis Among Other Methods of Research Synthesis. Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution, 1st edn, pp. 3–13. Princeton University Press, New Jersey (2013)

Lau, J., Ioannidis, J.P.A., Schmid, C.H.: Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann. Intern. Med. 127 (9), 820–826 (1997)

Lucas, P.J., et al.: Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology v. 7 , 2007.

Monforte-Royo, C., et al.: What lies behind the wish to hasten death? A systematic review and meta-ethnography from the perspective of patients. PLoS One 7 (5) (2012). ISSN 1932-6203

Morandi, M.I.W.M., Camargo, L.F.R.: Systematic Literature Review. Design Science Research: A Method for Science and Technology Advancement, 1st edn, pp. 141–172. Springer International Publishing, New York (2015)

Noblit, G.W., Hare, R.D.: Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies, 1st edn. SAGE Publications, Newbury Park (1988). ISBN 9780803930230

Pawson, R., et al.: Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 10 (SUPPL. 1), 21–34 (2005)

Popay, J., et al.: Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. In: ESRC Methods Programme, 92 p (2006). https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1018.4643

Saini, M., Shlonsky, A.: Systematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research, 1st edn, 223 p. Oxford University Press, New York (2012). ISBN 9780195387216

Sandelowski, M., Barroso, J.: Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology project. Qual. Health Res 13 (6), 781–820 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303013006003

Sandelowski, M., Barroso, J., Voils, C.I.: Using qualitative metasummary to synthesize qualitative and quantitative descriptive findings. Res. Nurs. Health 30 (1), 99–111 (2007)

Stern, P.N.: Grounded Theory Methodology: Its Uses and Processes. XII (1), (1980)

Straus, S.E., et al.: Introduction: engaging researchers on developing, using, and improving knowledge synthesis methods: a series of articles describing the results of a scoping review on emerging knowledge synthesis methods. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 73 (1), 15–18 (2016)

Strauss A, Corbin J.: Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques, 2nd edn, 272 p. SAGE Publications, Newbury Park (1990). ISBN 978-1412906449

Thomas, J., Harden, A., Newman, M.: Synthesis: Combining Results Systematically and Appropriately. An introduction to Systematic Reviews, 1st edn, p. 288. SAGE Publications, Los Angeles (2012)

Thomas, K.: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 264 p. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1962). ISBN 9780226458113

Walsh, D., Downe, S.: Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 50 (2), 204–211 (2005). ISSN 1365-2648

Weed, M.: A potential method for the interpretive synthesis of qualitative research: issues in the development of “meta-interpretation.” Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 11 (1), 13–28 (2008)

Whittemore, R., Knafl, K.: The integrative review: updated methodology. Methodol. Issues Nurs. Res. 52 (5), 546–553 (2005)

Yearworth, M., White, L.: The uses of qualitative data in multimethodology: developing causal loop diagrams during the coding process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 231 (1), 151–161 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2013.05.002

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Production and Systems Engineering, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, São Leopoldo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Ana Paula Cardoso Ermel

D. P. Lacerda

Maria Isabel W. M. Morandi

Leandro Gauss

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ana Paula Cardoso Ermel .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cardoso Ermel, A.P., Lacerda, D.P., Morandi, M.I.W.M., Gauss, L. (2021). Literature Synthesis. In: Literature Reviews. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75722-9_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75722-9_5

Published : 31 August 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-75721-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-75722-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Lydon and O'Leary libraries will be closing at 2:00pm on Wednesday, July 3rd , and will be closed on Thursday, July 4th . If you have any questions, please contact [email protected] .

- University of Massachusetts Lowell

- University Libraries

Literature Review Step by Step

- Refining Your Understanding

- Parts of a Literature Review

- Choosing a Topic

- Search Terms

- Peer Review

- Internet Sources

- Social Media Sources

- Information Landscape

About Literature Review

- From University of North Carolina A clear verbal description of the literature review process.

What is Synthesis?

"The combination of components or elements to form a connected whole" (OED)

Forming a synthesis between various ideas is the heart of your literature review, and once done, will be the core of your research paper. As a starting point try:

• finding ideas that are common or controversial • two or three important trends in the research • the most influential theories.

As you read keep these questions in mind:

• does the writer make any assumptions not supported by evidence? • what is the researcher's method? how does she gather data? • what ideas and which researchers are frequently referred to?

Some writers of Literature Review create a matrix for organizing their research articles.

This requires you to come up with a number of categories which grow out of your reading of the literature. As you read, write down ideas, words or controversies that occur frequently. Ask yourself why? What question are these different papers trying to answer?

This process will generate a number of categories, You can use these to create a table. The article below offers more information on this method of organizing your process.

- Creating a Matrix for Literature Review Synthesis

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Jan 22, 2024 2:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uml.edu/lit_review_general

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix

Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix

Published on July 4, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Synthesizing sources involves combining the work of other scholars to provide new insights. It’s a way of integrating sources that helps situate your work in relation to existing research.

Synthesizing sources involves more than just summarizing . You must emphasize how each source contributes to current debates, highlighting points of (dis)agreement and putting the sources in conversation with each other.

You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field or throughout your research paper when you want to position your work in relation to existing research.

Table of contents

Example of synthesizing sources, how to synthesize sources, synthesis matrix, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about synthesizing sources.

Let’s take a look at an example where sources are not properly synthesized, and then see what can be done to improve it.

This paragraph provides no context for the information and does not explain the relationships between the sources described. It also doesn’t analyze the sources or consider gaps in existing research.

Research on the barriers to second language acquisition has primarily focused on age-related difficulties. Building on Lenneberg’s (1967) theory of a critical period of language acquisition, Johnson and Newport (1988) tested Lenneberg’s idea in the context of second language acquisition. Their research seemed to confirm that young learners acquire a second language more easily than older learners. Recent research has considered other potential barriers to language acquisition. Schepens, van Hout, and van der Slik (2022) have revealed that the difficulties of learning a second language at an older age are compounded by dissimilarity between a learner’s first language and the language they aim to acquire. Further research needs to be carried out to determine whether the difficulty faced by adult monoglot speakers is also faced by adults who acquired a second language during the “critical period.”

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

To synthesize sources, group them around a specific theme or point of contention.

As you read sources, ask:

- What questions or ideas recur? Do the sources focus on the same points, or do they look at the issue from different angles?

- How does each source relate to others? Does it confirm or challenge the findings of past research?

- Where do the sources agree or disagree?

Once you have a clear idea of how each source positions itself, put them in conversation with each other. Analyze and interpret their points of agreement and disagreement. This displays the relationships among sources and creates a sense of coherence.

Consider both implicit and explicit (dis)agreements. Whether one source specifically refutes another or just happens to come to different conclusions without specifically engaging with it, you can mention it in your synthesis either way.

Synthesize your sources using:

- Topic sentences to introduce the relationship between the sources

- Signal phrases to attribute ideas to their authors

- Transition words and phrases to link together different ideas

To more easily determine the similarities and dissimilarities among your sources, you can create a visual representation of their main ideas with a synthesis matrix . This is a tool that you can use when researching and writing your paper, not a part of the final text.

In a synthesis matrix, each column represents one source, and each row represents a common theme or idea among the sources. In the relevant rows, fill in a short summary of how the source treats each theme or topic.

This helps you to clearly see the commonalities or points of divergence among your sources. You can then synthesize these sources in your work by explaining their relationship.

| Lenneberg (1967) | Johnson and Newport (1988) | Schepens, van Hout, and van der Slik (2022) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach | Primarily theoretical, due to the ethical implications of delaying the age at which humans are exposed to language | Testing the English grammar proficiency of 46 native Korean or Chinese speakers who moved to the US between the ages of 3 and 39 (all participants had lived in the US for at least 3 years at the time of testing) | Analyzing the results of 56,024 adult immigrants to the Netherlands from 50 different language backgrounds |

| Enabling factors in language acquisition | A critical period between early infancy and puberty after which language acquisition capabilities decline | A critical period (following Lenneberg) | General age effects (outside of a contested critical period), as well as the similarity between a learner’s first language and target language |

| Barriers to language acquisition | Aging | Aging (following Lenneberg) | Aging as well as the dissimilarity between a learner’s first language and target language |

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Synthesizing sources means comparing and contrasting the work of other scholars to provide new insights.

It involves analyzing and interpreting the points of agreement and disagreement among sources.

You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field of research or throughout your paper when you want to contribute something new to existing research.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

Topic sentences help keep your writing focused and guide the reader through your argument.

In an essay or paper , each paragraph should focus on a single idea. By stating the main idea in the topic sentence, you clarify what the paragraph is about for both yourself and your reader.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/synthesizing-sources/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, signal phrases | definition, explanation & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to find sources | scholarly articles, books, etc., get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Literature Reviews

- Introduction

- Tutorials and resources

- Step 1: Literature search

- Step 2: Analysis, synthesis, critique

- Step 3: Writing the review

If you need any assistance, please contact the library staff at the Georgia Tech Library Help website .

Analysis, synthesis, critique

Literature reviews build a story. You are telling the story about what you are researching. Therefore, a literature review is a handy way to show that you know what you are talking about. To do this, here are a few important skills you will need.

Skill #1: Analysis

Analysis means that you have carefully read a wide range of the literature on your topic and have understood the main themes, and identified how the literature relates to your own topic. Carefully read and analyze the articles you find in your search, and take notes. Notice the main point of the article, the methodologies used, what conclusions are reached, and what the main themes are. Most bibliographic management tools have capability to keep notes on each article you find, tag them with keywords, and organize into groups.

Skill #2: Synthesis

After you’ve read the literature, you will start to see some themes and categories emerge, some research trends to emerge, to see where scholars agree or disagree, and how works in your chosen field or discipline are related. One way to keep track of this is by using a Synthesis Matrix .

Skill #3: Critique

As you are writing your literature review, you will want to apply a critical eye to the literature you have evaluated and synthesized. Consider the strong arguments you will make contrasted with the potential gaps in previous research. The words that you choose to report your critiques of the literature will be non-neutral. For instance, using a word like “attempted” suggests that a researcher tried something but was not successful. For example:

There were some attempts by Smith (2012) and Jones (2013) to integrate a new methodology in this process.

On the other hand, using a word like “proved” or a phrase like “produced results” evokes a more positive argument. For example:

The new methodologies employed by Blake (2014) produced results that provided further evidence of X.

In your critique, you can point out where you believe there is room for more coverage in a topic, or further exploration in in a sub-topic.

Need more help?

If you are looking for more detailed guidance about writing your dissertation, please contact the folks in the Georgia Tech Communication Center .

- << Previous: Step 1: Literature search

- Next: Step 3: Writing the review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 11:21 AM

- URL: https://libguides.library.gatech.edu/litreview

Writing the Literature Review

- Getting Started

- Step 1: Choose A Topic

- Step 2: Find Information

- Step 3: Evaluate

- Step 4: Take Notes

- Step 5: Synthesize

- Step 6: Stay Organized

- Write the Review

Synthesizing

What is "Synthesis"?

Synthesis?

Synthesis refers to combining separate elements to create a whole. When reading through your sources (peer reviewed journal articles, books, research studies, white papers etc.) you will pay attention to relationships between the studies, between groups in the studies, and look for any pattterns, similarities or differences. Pay attention to methodologies, unexplored themes, and things that may represent a "gap" in the literature. These "gaps" will be things you will want to be sure to identify in your literature review.

- Using a Synthesis Matrix to Plan a Literature Review Introduction to synthesis matrices, and explanation of the difference between synthesis and analysis. (Geared towards Health Science/ Nursing but applicable for other literature reviews) ***Includes a synthesis matrix example***

- Using a Spider Diagram Organize your thoughts with a spider diagram

Ready, Set...Synthesize

- Create an outline that puts your topics (and subtopics) into a logical order

- Look at each subtopic that you have identified and determine what the articles in that group have in common with each other

- Look at the articles in those subtopics that you have identified and look for areas where they differ.

- If you spot findings that are contradictory, what differences do you think could account for those contradictions?

- Determine what general conclusions can be reported about that subtopic, and how it relates to the group of studies that you are discussing

- As you write, remember to follow your outline, and use transitions as you move between topics

Galvan, J. L. (2006). Writing literature reviews (3rd ed.). Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing

- << Previous: Step 4: Take Notes

- Next: Step 6: Stay Organized >>

- Last Updated: Sep 27, 2023 11:22 AM

- URL: https://guides.mga.edu/TheLiteratureReviewANDYou

478-471-2709 for the Macon campus library | 478-934-3179 for the Roberts Memorial Library at the Cochran campus | 478-275-6772 for the Dublin campus library

478-374-6833 for the Eastman campus library | 478-929-6804 for the Warner Robins campus library | On the Go? Text-A-Librarian: 478-285-4898

Middle Georgia State University Library

Book an Appointment With a Librarian

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.