Working Papers

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis working papers are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment.

Recent Working Papers

After 40 Years, How Representative Are Labor Market Outcomes in the NLSY79? by Alexander Bick, Adam Blandin, and Richard Rogerson Working Paper 2024-010B updated April 2024

In 1979, the National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1979 (NLSY79) began following a group of US residents born between 1957 and 1964. It has continued to re-interview these same individuals for more than four decades. Despite this long sampling period, attrition remains modest. This paper shows that after 40 years of data collection, the remaining NLYS79 sample continues to be broadly representative of their national cohorts with regard to key labor market outcomes. For NLSY79 age cohorts, life-cycle profiles of employment, hours worked, and earnings are comparable to those in the Current Population Survey. Moreover, average lifetime earnings over the age range 25 to 55 closely align with the same measure in Social Security Administration data. Our results suggest that the NLSY79 can continue to provide useful data for economists and other social scientists studying life-cycle and lifetime labor market outcomes, including earnings inequality.

Diffusion of new technologies by Nicholas Bloom, Marcela Carvalho, Tarek Hassan, Aakash Kalyani, and Josh Lerner Working Paper 2024-009A added April 2024

CORRECT ORDER OF AUTHORS: Aakash Kalyani, Nicholas Bloom, Marcela Carvalho, Tarek Hassan, Josh Lerner, and Ahmed Tahoun. We identify phrases associated with novel technologies using textual analysis of patents, job postings, and earnings calls, enabling us to identify four stylized facts on the diffusion of jobs relating to new technologies. First, the development of new technologies is geographically highly concentrated, more so even than overall patenting: 56% of the economically most impactful technologies come from just two U.S. locations, Silicon Valley and the Northeast Corridor. Second, as the technologies mature and the number of related jobs grows, hiring spreads geographically. But this process is very slow, taking around 50 years to disperse fully. Third, while initial hiring in new technologies is highly skill biased, over time the mean skill level in new positions declines, drawing in an increasing number of lower-skilled workers. Finally, the geographic spread of hiring is slowest for higher-skilled positions, with the locations where new technologies were pioneered remaining the focus for the technology’s high-skill jobs for decades.

The Creativity Decline: Evidence from US Patents by Aakash Kalyani Working Paper 2024-008A added April 2024

Economists have long struggled to understand why aggregate productivity growth has dropped in recent decades while the number of new patents filed has steadily increased. I offer an explanation for this puzzling divergence: the creativity embodied in US patents has dropped dramatically over time. To separate creative from derivative patents, I develop a novel, text-based measure of patent creativity: the share of technical terminology that did not appear in previous patents. I show that only creative and not derivative patents are associated with significant improvements in firm level productivity. Using the measure, I show that inventors on average file creative patents upon entry, and file derivative patents with more experience. I embed this life-cycle of creativity in a growth model with endogenous creation and imitation of technologies. In this model, falling population growth explains 27% of the observed decline in patent creativity, 30% of the slowdown in productivity growth, and 64% of the increase in patenting.

Consumption Dynamics and Welfare Under Non-Gaussian Earnings Risk by Fatih Guvenen, Rocio Madera, and Serdar Ozkan Working Paper 2024-007A added April 2024

CORRECT ORDER OF AUTHORS: Fatih Guvenen, Serdar Ozkan, and Rocio Madera. The order of coauthors has been assigned randomly using AEA’s Author Randomization Tool. Recent empirical studies document that the distribution of earnings changes displays substantial deviations from lognormality: in particular, earnings changes are negatively skewed with extremely high kurtosis (long and thick tails), and these non-Gaussian features vary substantially both over the life cycle and with the earnings level of individuals. Furthermore, earnings changes display nonlinear (asymmetric) mean reversion. In this paper, we embed a very rich “benchmark earnings process” that captures these non-Gaussian and nonlinear features into a lifecycle consumption-saving model and study its implications for consumption dynamics, consumption insurance, and welfare. We show four main results. First, the benchmark process essentially matches the empirical lifetime earnings inequality—a first-order proxy for consumption inequality—whereas the canonical Gaussian (persistent-plus-transitory) process understates it by a factor of five to ten. Second, the welfare cost of idiosyncratic risk implied by the benchmark process is between two-to-four times higher than the canonical Gaussian one. Third, the standard method in the literature for measuring the pass-through of income shocks to consumption—can significantly overstate the degree of consumption smoothing possible under non-Gaussian shocks. Fourth, the marginal propensity to consume out of transitory income (e.g., from a stimulus check) is higher under non-Gaussian earnings risk.

Sluggish news reactions: A combinatorial approach for synchronizing stock jumps by Nabil Bouamara, Kris Boudt, Sébastien Laurent, and Christopher J. Neely Working Paper 2024-006A added March 2024

Stock prices often react sluggishly to news, producing gradual jumps and jump delays. Econometricians typically treat these sluggish reactions as microstructure effects and settle for a coarse sampling grid to guard against them. Synchronizing mistimed stock returns on a fine sampling grid allows us to better approximate the true common jumps in related stock prices.

The Adoption of Non-Rival Inputs and Firm Scope by Xian Jiang and Hannah Rubinton Working Paper 2024-005C updated April 2024

Custom software is distinct from other types of capital in that it is non-rival---once a firm makes an investment in custom software, it can be used simultaneously across its many establishments. Using confidential US Census data, we document that while firms with more establishments are more likely to invest in custom software, they spend less on it as a share of total capital expenditure. We explain these empirical patterns by developing a model that incorporates the non-rivalry of custom software. In the model, firms choose whether to adopt custom software, the intensity of their investment, and their scope, balancing the cost of managing multiple establishments with the increasing returns to scope from the non-rivalrous custom software investment. Using the calibrated model, we assess the extent to which the decline in the rental rate of custom software over the past 40 years can account for a number of macroeconomic trends, including increases in firm scope and concentration.

Trade Risk and Food Security by Tasso Adamopoulos and Fernando Leibovici Working Paper 2024-004B updated March 2024

We study the role of international trade risk for food security, the patterns of production and trade across sectors, and its implications for policy. We document that food import dependence across countries is associated with higher food insecurity, particularly in low-income countries. We provide causal evidence on the role of trade risk for food security by exploiting the exogeneity of the Ukraine-Russia war as a major trade disruption limiting access to imports of critical food products. Using micro-level data from Ethiopia, we empirically show that districts relatively more exposed to food imports from the conflict countries experienced a significant increase in food insecurity by consuming fewer varieties of foods. Motivated by this evidence, we develop a multi-country multi-sector model of trade and structural change with stochastic trade costs to study the impact and policy implications of trade risk. In the model, importers operate subject to limited liability and trade off the production cost advantage against the risk of higher trade costs when sourcing goods internationally. We find that trade risk can threaten food security, with substantial quantitative effects on trade flows and the sectoral composition of economic activity. We study the desirability of trade policy and production subsidies in partially mitigating exposure to trade risk and diversifying domestic economic activity.

Where Did the Workers Go? The Effect of COVID Immigration Restrictions on Post-Pandemic Labor Market Tightness by Maggie Isaacson, Cassie Marks, Lowell R. Ricketts, and Hannah Rubinton Working Paper 2024-003B updated January 2024

During the COVID pandemic there were unprecedented shortfalls in immigration. At the same time, during the economic recovery, the labor market was tight, with the number of vacancies per unemployed worker reaching 2.5, more than twice its pre-pandemic average. In this paper, we investigate whether these two trends are linked. We do not find evidence to support the hypothesis that the immigration shortfalls caused the tight labor market for two reasons. First, at the peak, we were missing about 2 million immigrant workers, but this number had largely recovered by February 2022 just as the labor market was becoming tight. Second, states, cities, and industries that were most impacted by the immigration restrictions did not have larger increases in labor market tightness. We build a shift-share instrument to examine the causal impact of the immigration restrictions and still find no evidence to support the hypothesis that the immigration restrictions were the underlying cause of increased labor market tightness.

Structural Change and the Rise in Markups by Ricardo Marto Working Paper 2024-002B updated January 2024

Is the recent rise in markups caused by increased monopoly power or is it a natural consequence of structural change? I show that the rise in aggregate markups has been driven by a reallocation of market share away from non-services to services-producing firms and a faster increase of services’ markups. I develop a two-sector model to assess the sources of the rise in markups, in which the two forces of structural change play opposing roles. On one hand, an increase in the relative productivity of manufacturing leads to a decline of the relative price of manufactured goods and to an increase of the goods markups. On the other hand, the increase in incomes that triggers the rise of the services sector leads to higher markups for firms in services. I show that the rise in markups is in line with the rise of the services sector and the fall of the relative price of manufactured goods, and may not necessarily reflect a decline of competition. I provide novel experimental evidence supporting the notion that the price elasticity of demand decreases with income.

Heterogeneous Responses to Job Mobility Shocks in a HANK Model with a Frictional Labor Market by Serdar Birinci, Fatih Karahan, Yusuf Mercan, and Kurt See Working Paper 2024-001B updated January 2024

Cross-border Patenting, Globalization, and Development by Jesse LaBelle, Inmaculada Martinez-Zarzoso, Ana Maria Santacreu, and Yoto Yotov Working Paper 2023-031B updated December 2023

We build a stylized model that captures the relationships between cross-border patenting, globalization, and development. Our theory delivers a gravity equation for cross-border patents. To test the model’s predictions, we compile a new dataset that tracks patents within and between countries and industries, for 1980-2019. The econometric analysis reveals a strong, positive impact of policy and globalization on cross-border patent flows, especially from North to South. A counterfactual welfare analysis suggests that the increase in patent flows from North to South has benefited both regions, with South gaining more than North post-2000, thus lowering real income inequality in the world.

Risk Management in Monetary Policymaking: The 1994-95 Fed Tightening Episode by Kevin L. Kliesen Working Paper 2023-030A added December 2023

The 1994-95 Fed tightening episode was one of the most notable in the Fed’s history. First, the FOMC raised the policy rate by 300 basis points in a year, even though headline and core inflation were trending lower prior to the liftoff that occurred in February 1994. Second, the Fed’s actions caught the Treasury market by surprise, triggering a sharp decline in long-term bond prices. Third, Fed Chair Alan Greenspan and the Federal Open Market Committee were regularly surprised that inflation was not rising by more than the forecasts suggested during the episode. This article presents some evidence that the Greenbook forecast systemically, albeit modestly, overpredicted CPI inflation during the tightening period. Greenspan eventually concluded that the nascent strengthening in labor productivity growth that was a key factor in restraining the growth of unit labor costs, and thus in keeping inflation pressures in check. At the same time, the success of the episode stemmed importantly from the decision by Greenspan and the FOMC to increase the policy rate to a level deemed restrictive for most of 1995. This effort reduced longer-run inflation expectations without triggering a recession. By that metric the 1994-95 tightening episode was a roaring success. Although not the focus of this article, the 1994-95 tightening episode holds important lessons for the FOMC in late 2023, which is attempting to defuse a sharp and unexpected increase in headline and core inflation to levels not seen since the early 1980s without triggering a recession.

Bootstrapping out-of-sample predictability tests with real-time data by Silvia Goncalves, Michael W. McCracken, and Yongxu Yao Working Paper 2023-029A added December 2023

In this paper we develop a block bootstrap approach to out-of-sample inference when real-time data are used to produce forecasts. In particular, we establish its first-order asymptotic validity for West-type (1996) tests of predictive ability in the presence of regular data revisions. This allows the user to conduct asymptotically valid inference without having to estimate the asymptotic variances derived in Clark and McCracken’s (2009) extension of West (1996) when data are subject to revision. Monte Carlo experiments indicate that the bootstrap can provide satisfactory finite sample size and power even in modest sample sizes. We conclude with an application to inflation forecasting that adapts the results in Ang et al. (2007) to the presence of real-time data.

What about Japan? by YiLi Chien, Harold L. Cole, and Hanno Lustig Working Paper 2023-028B updated November 2023

As a result of the BoJ's large-scale asset purchases, the consolidated Japanese government borrows mostly at the floating rate from households and invests in longer-duration risky assets to earn an extra 3% of GDP. We quantify the impact of Japan's low-rate policies on its government and households. Because of the duration mismatch on the government balance sheet, the government's fiscal space expands when real rates decline, allowing the government to keep its promises to older Japanese households. A typical younger Japanese household does not have enough duration in its portfolio to continue to finance its spending plan and will be worse off. Low-rate policies tax younger, poorer and less financially sophisticated households.

A journal ranking based on central bank citations by Raphael Auer, Giulio Cornelli, and Christian Zimmermann Working Paper 2023-027A added October 2023

We present a ranking of journals geared toward measuring the policy relevance of research. We compute simple impact factors that count only citations made in central bank publications, such as their working paper series. Whereas this ranking confirms the policy relevance of the major general interest journals in the field of economics, the major finance journals fare less favourably. Journals specialising in monetary economics, international economics and financial intermediation feature highly, but surprisingly not those specialising in econometrics. The ranking is topped by the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, followed by the Quarterly Journal of Economics and the Journal of Monetary Economics, the American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, and the Journal of Political Economy.

On the Transition to Modern Growth by B. Ravikumar and Guillaume Vandenbroucke Working Paper 2023-026B updated October 2023

We study a simple model where a single good can be produced using a diminishing-returns technology (Malthus) and a constant-returns technology (Solow). The economy's output exhibits three stages: (i) stagnation, (ii) transition with increasing growth, and (iii) constant growth in the long run. We map the Malthus technology to agriculture and show that the share of agricultural employment is sufficient to determine the onset of economic transition. Using data on the share, we estimate the onset of transition for the U.S. and Western Europe without using output data. Our model implies that output growth during the transition is a first-order autoregressive process and that the rate of decline in the share of agricultural employment is a sufficient statistic to describe the output growth. Quantitatively, while there is no a priori reason why agricultural employment would pin down output dynamics over two centuries, the autoregressive coefficient on the output growth process is practically the same as the one implied by the rate of decline in the share of agricultural employment.

Income Differences and Health Disparities: Roles of Preventive vs. Curative Medicine by Serdar Ozkan Working Paper 2023-025C updated April 2024

Using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) I find that early in life the rich spend significantly more on health care, whereas from middle to very old age the poor outspend the rich by 25% in the US. Furthermore, while low-income individuals are less likely to incur medical expenses, they are more prone to experiencing extreme expenses when they do seek care. To account for these facts, I develop and estimate a life-cycle model of two types of health capital: physical and preventive. Physical health capital determines survival probabilities, whereas preventive health capital governs the distribution of shocks to physical health capital, thereby controlling life expectancy. Moreover, I incorporate key features of the US health care system, including private and public health insurance. Because of their lower marginal utility of consumption, the rich spend more on preventive care, resulting in milder health shocks (and lower curative medical expenditures) in old age compared to the poor. Notably, public insurance, which by design covers large expenditures, amplifies these differences by hampering the poor's incentives to invest in preventive health. Therefore, the model also implies a widening life expectancy gap between income groups in response to rising inequality. Policy experiments suggest that expanding health insurance coverage and subsidizing preventive care to encourage health care use by the poor early in life can generate substantial welfare gains, even when accounting for the higher taxes required to finance them.

Real Wage Growth at the Micro Level by Victoria Gregory and Elisabeth Harding Working Paper 2023-024B updated July 2023

This paper investigates patterns in real wage growth in 2022 to determine whether wages have kept up with rising price levels, and how this differs among labor market participants. Using the CPS for wages and imputing expenditure data from the CEX, we measure separately nominal wage growth and inflation rates at the micro level. We find that there is more heterogeneity in the former, meaning that when we combine them, an individual’s real wage growth is primarily driven by their nominal wage growth. In 2022, 57% of individuals experienced negative real wage growth, with older and less educated workers, as well as job-stayers, being hit the hardest. Conversely, younger and highly educated workers, as well as job-switchers, had higher real wage growth.

Marriage Market Sorting in the U.S. by Anton Cheremukhin, Paulina Restrepo-Echavarria, and Antonella Tutino Working Paper 2023-023A added September 2023

We study the multidimensional sorting of males and females in the U.S. marriage market over the past decade using a model of targeted search. We find strong vertical sorting on income and education, and horizontal sorting on race. We find that women put significant effort into targeting men at the top of the desirability scale, while men put less effort and target women with similar characteristics. We find no improvement in quality of matching and no noticeable changes in sorting patterns or individual search behavior, despite rapid improvement in search technology. Finally, we find that targeted search substantially reduces income inequality across married couples, even when compared with random matching, by producing a large number of matches between low income and high income individuals.

Uncovering the Differences among Displaced Workers: Evidence from Canadian Job Separation Records by Serdar Birinci, Youngmin Park, Thomas Pugh, and Kurt See Working Paper 2023-022B updated October 2023

We revisit the measurement of the sources and consequences of job displacement using Canadian job separation records. To circumvent administrative data limitations, conventional approaches address selection by identifying displacement effects through mass-layoff separations, which are interpreted as involuntary. We refine this procedure and find that only a quarter of mass-layoff separations are indeed layoffs. Isolating mass-layoff separations that reflect involuntary displacement, we find twice the earnings losses relative to existing estimates. We uncover heterogeneity in losses for separations with different reason and timing, ranging from 15 percent for quits after a mass layoff to 60 percent for layoffs before it.

Impulse Response Functions for Self-Exciting Nonlinear Models by Neville Francis, Michael T. Owyang, and Daniel Soques Working Paper 2023-021A added September 2023

We calculate impulse response functions from regime-switching models where the driving variable can respond to the shock. Two methods used to estimate the impulse responses in these models are generalized impulse response functions and local projections. Local projections depend on the observed switches in the data, while generalized impulse response functions rely on correctly specifying regime process. Using Monte Carlos with different misspecifications, we determine under what conditions either method is preferred. We then extend model-average impulse responses to this nonlinear environment and show that they generally perform better than either generalized impulse response functions and local projections. Finally, we apply these findings to the empirical estimation of regime-dependent fiscal multipliers and find multipliers less than one and generally small differences across different states of slack.

Growth-at-Risk is Investment-at-Risk by Aaron Amburgey and Michael W. McCracken Working Paper 2023-020A added August 2023

We investigate the role financial conditions play in the composition of U.S. growth-at-risk. We document that, by a wide margin, growth-at-risk is investment-at-risk. That is, if financial conditions indicate U.S. real GDP growth will be in the lower tail of its conditional distribution, we know that the main contributor is a decline in investment. Consumption contributes under extreme financial stress. Government spending and net exports do not play a role.

Trade Liberalization versus Protectionism: Dynamic Welfare Asymmetries by B. Ravikumar, Ana Maria Santacreu, and Michael J. Sposi Working Paper 2023-019C updated January 2024

We investigate whether the losses from an increase in trade costs (protectionism) are equal to the gains from a symmetric decrease in trade costs (liberalization). We incorporate dynamics through capital accumulation into a multicountry trade model and show that the welfare changes are asymmetric: Losses from protectionism are smaller than the gains from liberalization. In contrast, standard static trade models imply that the losses equal the gains. The intuition for asymmetry in our model is that, following protectionism, the economy can coast on its previously accumulated capital stock, so higher trade costs do not imply large losses immediately. We develop an accounting device to decompose the source of welfare asymmetries into three time-varying contributions: share of income allocated to consumption, measured productivity, and capital stock. Asymmetry in capital accumulation is the largest contributing factor, and measured productivity is the smallest.

How Much Should We Trust Regional-Exposure Designs? by Jeremy Majerovitz and Karthik Sastry Working Paper 2023-018A added August 2023

Many prominent studies in macroeconomics, labor, and trade use panel data on regions to identify the local effects of aggregate shocks. These studies construct regional-exposure instruments as an observed aggregate shock times an observed regional exposure to that shock. We argue that the most economically plausible source of identification in these settings is uncorrelatedness of observed and unobserved aggregate shocks. Even when the regression estimator is consistent, we show that inference is complicated by cross-regional residual correlations induced by unobserved aggregate shocks. We suggest two-way clustering, two-way heteroskedasticity- and autocorrelation-consistent standard errors, and randomization inference as options to solve this inference problem. We also develop a feasible optimal instrument to improve efficiency. In an application to the estimation of regional fiscal multipliers, we show that the standard practice of clustering by region generates confidence intervals that are too small. When we construct confidence intervals with robust methods, we can no longer reject multipliers close to zero at the 95% level. The feasible optimal instrument more than doubles statistical power; however, we still cannot reject low multipliers. Our results underscore that the precision promised by regional data may disappear with correct inference.

Decomposing the Government Transfer Multiplier by Timothy Conley, Bill Dupor, Rong Li, and Yijiang Zhou Working Paper 2023-017C updated July 2023

We estimate the local, spillover and aggregate causal effects of government transfers on personal income. We identify exogenous changes in federal transfers to residents at the state-level using legislated social security cost-of-living adjustments between 1952 and 1974. Each effect is measured as a multiplier: the change in personal income in response to a one unit change in transfers. The local multiplier, i.e., the effect of own-state transfers on own-state income holding fixed other state's income, at a four-quarter horizon is approximately 3.4. The cross-state spillover multiplier is about -0.7, but not statistically different from zero. The aggregate multiplier, i.e., the sum of its local and spillover components, equals 2.7. More generally, our paper provides a template for conducting inference that decomposes an aggregate effect into its local and spillover components.

Systemic Tail Risk: High-Frequency Measurement, Evidence and Implications by Deniz Erdemlioglu, Christopher J. Neely, and Xiye Yang Working Paper 2023-016A added July 2023

We develop a new framework to measure market-wide (systemic) tail risk in the cross-section of high-frequency stock returns. We estimate the time-varying jump intensities of asset prices and introduce a testing approach that identifies multi-asset tail risk based on the release times of scheduled news announcements. Using high-frequency data on individual U.S. stocks and sector-specific ETF portfolios, we find that most of the FOMC announcements create systemic left tail risk, but there is no evidence that macro announcements do so. The magnitude of the tail risk induced by Fed news varies over the business cycle, peaks during the global financial crisis and remains high over different phases of unconventional monetary policy. We use our approach to construct a Fed-induced systemic tail risk (STR) indicator. STR helps explain the pre-FOMC announcement drift and significantly increases variance risk premia, particularly for the meetings without press conferences.

Artificial Intelligence and Inflation Forecasts by Miguel Faria e Castro and Fernando Leibovici Working Paper 2023-015D updated February 2024

We explore the ability of Large Language Models (LLMs) to produce in-sample conditional inflation forecasts during the 2019-2023 period. We use a leading LLM (Google AI's PaLM) to produce distributions of conditional forecasts at different horizons and compare these forecasts to those of a leading source, the Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF). We find that LLM forecasts generate lower mean-squared errors overall in most years, and at almost all horizons. LLM forecasts exhibit slower reversion to the 2% inflation anchor.

Immigration from a terror-prone nation: destination nation’s optimal immigration and counterterrorism policies by Subhayu Bandyopadhyay, Khusrav Gaibulloev, and Todd Sandler Working Paper 2023-014A added June 2023

The paper presents a two-country model in which a destination country chooses its immigration quota and proactive counterterrorism actions in response to immigration from a terror-plagued source country. After the destination country fixes its two policies, immigrants decide between supplying labor or conducting terrorist attacks, which helps determine equilibrium labor supply and wages. The analysis accounts for the marginal disutility of lost rights/freedoms stemming from stricter counterterror measures as well the inherent radicalization of migrants. Comparative statics involve changes to those two parameters. For example, an enhanced importance attached to lost rights is shown to limit immigration quotas and counterterrorism actions. In contrast, increased source-country radicalization reduces immigration quotas but has an ambiguous effect on optimal proactive measures. Extensions involving defensive policies and destination-country citizens radicalization are considered.

Mind Your Language: Market Responses to Central Bank Speeches by Maximilian Ahrens, Deniz Erdemlioglu, Michael McMahon, Christopher J. Neely, and Xyie Yang Working Paper 2023-013B updated February 2024

Researchers have carefully studied post-meeting central bank communication and have found that it often moves markets, but they have paid less attention to the more frequent central bankers’ speeches. We create a novel dataset of US Federal Reserve speeches and develop supervised multimodal natural language processing methods to identify how monetary policy news affect financial volatility and tail risk through implied changes in forecasts of GDP, inflation, and unemployment. We find that news in central bankers’ speeches can help explain volatility and tail risk in both equity and bond markets. Our results challenge the conventional view that central bank communication primarily resolves uncertainty and indicate that markets attend to speech signals more closely during abnormal GDP and inflation regimes. Our analysis also reveals that the views of Fed members (i.e., hawkish versus dovish) tend to play a marginal role in terms of the strength of the speech signals. Looking at the speeches by the Fed Chair, we find that the Chair signals produce a larger tail risk compared to non-Chair signals, and the estimated magnitude of the market responses depends on the position of the officials (i.e., the Fed Chair or other Fed member).

Time Averaging Meets Labor Supplies of Heckman, Lochner, and Taber by Sebastian Graves, Victoria Gregory, Lars Ljungqvist, and Thomas J. Sargent Working Paper 2023-012A added May 2023

We incorporate time-averaging into the canonical model of Heckman, Lochner, and Taber (1998) (HLT) to study retirement decisions, government policies, and their interaction with the aggregate labor supply elasticity. The HLT model forced all agents to retire at age 65, while our model allows them to choose career lengths. A benchmark social security system puts all of our workers at corner solutions of their career-length choice problems and lets our model reproduce HLT model outcomes. But alternative tax and social security arrangements dislodge some agents from those corners, bringing associated changes in equilibrium prices and human capital accumulation decisions. A reform that links social security benefits to age but not to employment status eliminates the implicit tax on working beyond 65. High taxes with revenues returned lump-sum keep agents off corner solutions, raising the aggregate labor supply elasticity and threatening to bring about a “dual labor market” in which many people decide not to supply labor.

Next 30 Working Papers

- Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Related Links

- Economist Pages

- JEL Classification System

- Fed In Print

SUBSCRIBE TO THE RESEARCH DIVISION NEWSLETTER

Research division.

- Legal and Privacy

One Federal Reserve Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63102

Information for Visitors

Monetary Economics

Adrien Auclert

Darrell Duffie

Robert Hall

Thomas J. Sargent

John B. Taylor

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, monetary policy and market interest rates: literature review using text analysis.

International Journal of Development Issues

ISSN : 1446-8956

Article publication date: 17 August 2021

Issue publication date: 25 August 2021

This paper aims to examine the relationship between monetary policy and market interest rates. This paper examines the efficiency of interest rate channel used in monetary regulation as well as implementation of monetary policy under low interest rates. This paper examines and reviews the scientific literature published over the past 30 years to determine primary research areas, to summarize their results and to identify appropriate measures of monetary policy to be used in practice in changing economic environment.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper reviews 94 studies focused on the relationship between monetary policy and market interest rates in terms of meeting the goals of macroeconomic regulation. The articles are selected on the basis of Scopus citation and bibliometric analysis. A major feature of this paper is the use of text analysis (data preparation, frequency of terms and collocations use, examination of relationships between terms, use of principal component analysis to determine research thematic areas). Using the method of principal component analysis while studying abstracts this paper reveals thematic areas of the research. Thus, the conducted text analysis provides unbiased results.

First, this paper examines the whole complex of relationships between monetary policy of central banks and market interest rates. Second, this research reviews a wide range of literature including recent studies focused on specific features of monetary policy under low and negative rates. Third, this study identifies and summarizes the thematic areas of all the researches using text analysis (transmission mechanism of monetary policy, efficiency of zero interest rate policy, monetary policy and term structure of interest rates, monetary policy and interest rate risk of banks, monetary policy of central banks and financial stability). Finally, this paper presents the most important findings of the studied articles related to the current situation and trends on the financial market as well as further research opportunities. This paper finds the principal results of studies on significant issues of monetary policy in terms of its efficiency under low interest rates, influence of its instruments on term structure of interest rates and role of banking sector in implementation of transmission mechanism of monetary policy.

Research limitations/implications

The limitation of the review is examining articles for the study period of 30 years.

Practical implications

Central banks of emerging economies should apply the instruments and results of the countries' monetary policies reviewed in this paper. Using text analysis this paper reveals the main thematic areas and summarizes findings of the articles under study. The analysis allows presenting the main ideas related to current economic situation.

Social implications

The findings are of great value for adjusting the monetary policy of central banks. Also, these are important for people because these show the significant role of monetary policy for the economic growth.

Originality/value

Using text analysis this paper reveals the main thematic areas (transmission mechanism of monetary policy, efficiency of zero interest rate policy, monetary policy and term structure of interest rates, monetary policy and interest rate risk of banks, monetary policy of central banks and financial stability) and summarizes findings of the articles under study. The analysis allows defining the current ideas relevant to the monetary policy of developing countries. It is important for central banks because it examines the monetary policy problems and proposes optimal solutions.

- Monetary policy

- Interest rates

- Interest rate channel

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Associate Professor Ludmila Vinogradova for assistance in translation and Fedor Fedorov for help in text analysis.

Fedorova, E. and Meshkova, E. (2021), "Monetary policy and market interest rates: literature review using text analysis", International Journal of Development Issues , Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 358-373. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJDI-02-2021-0049

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Monetary Economics

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Macroeconomics Follow Following

- Monetary Policy Follow Following

- Economics Follow Following

- Financial Economics Follow Following

- International Economics Follow Following

- Econometrics Follow Following

- International Macroeconomics Follow Following

- International Trade Follow Following

- Development Economics Follow Following

- Development Econmomics Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Modern Monetary Theory: A Solid Theoretical Foundation of Economic Policy?

- Open access

- Published: 25 May 2021

- Volume 49 , pages 173–186, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Aloys L. Prinz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9198-5292 1 &

- Hanno Beck 2

8266 Accesses

3 Citations

26 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper shows that so-called modern monetary theory (MMT) lacks a sound economic foundation for its far-reaching policy recommendations. This paper’s main contribution to the literature concerns the theoretical foundation of MMT. A simple macroeconomic model shows that MMT is indistinguishable from the Keynesian cross model, as well as a neoclassical macroeconomic model, even when taking account of money in the sense of MMT. This result is in stark contrast to the claims of MMT proponents. Accordingly, it is asserted that MMT is a fundamentally new theory of money and monetary economics. However, MMT is admittedly based on the functional finance concept of the 1940s and money is modelled as an accounting identity. In addition, the fundamental connection between government expenditures for goods and services and the steady state equilibrium value of the national income, the so-called fiscal stance, is a well-known result that is not only consistent with MMT. The interpretation of the fiscal stance, in combination with the accounting identity for money, is a major issue because an equilibrium condition should have a certain causal direction of effects. Based on this reading of the equilibrium condition, policy recommendations encompass the fiscal dominance of monetary policy via monetization of public debt, a job guarantee by the state, along with a so-called Green New Deal. According to the results of this paper, these policy recommendations cannot be justified with MMT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Monetary Policy Framework

Monetary policy framework in India

Monetary Policy Framework in India

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, a macroeconomic theory, modern monetary theory (MMT) (also dubbed modern money theory), has become a hot topic in United States (U.S.) politics. Stephanie Kelton, a proponent of this theory, was among the advisers of Bernie Sanders in the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. Her contemporary, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a popular member of the Democratic Party in the U.S., seems to also adhere to MMT. MMT offers politicians what they want most: a simple justification for policies they want to carry out. A case in point is active U.S. labor market policy. The U.S. public expenditures in this policy area are very low in comparison to all other countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Council of Economic Advisers, 2016 ). After the near meltdown of the financial system and the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, attitudes towards active labor market and social policies might have changed. Therefore, MMT may provide a welcome academic justification for these policies. Moreover, the popularization of MMT through the blogosphere may have a profound effect on U.S. politics and economic policy in the 2020s and 2030s (Brady 2020 ).

A special feature of MMT and its policy recommendations is public debt. According to MMT, public expenditures can be financed by public debt or even by printing more money without negative economic side effects such as inflation, crowding-out of investments or national insolvency (Forstater 1999 ; Mosler 1998 ). The only precondition is that the respective state has its own currency. This is the most provocative conclusion of MMT proponents.

MMT is not a new theory that emerged from the financial crisis of 2008. Most of the policy recommendations can be found in the work of Lerner ( 1943 , 1944 , 1951 ), dubbed functional finance, as also mentioned by MMT proponents. The theory itself is Post-Keynesian and monetary. Post-Keynesian economics (Arestis 1996 ; Lavoie 2009 ) is the general heading for very different economic concepts and theories that rely on Keynesian economics, but that do not accept New Keynesian concepts (Dixon and Rankin, 1995 ). Meanwhile, economists of this tradition formed a group whose common feature is a so-called coherent financial stock-flow accounting framework (Godley and Lavoie, 2012 , p. 12, who also sketch the development of MMT; Nikiforos and Zezza, 2017 ). As will become clear in the following, ex post accounting identities play a crucial role in MMT.

Literature Review

Although there are a number of recent assessments of MMT, these contributions either do not contain a formal analysis (Brady 2020 ; Coats 2019 ; Epstein 2020 ; Hartley 2020 ; Newman 2020 ; Palley 2015a ; Skousen 2020 ) or the formal analysis is a bit too sophisticated to isolate exactly where the theoretical foundation of MMT fails (Palley 2015b ). Palley ( 2015a ) discussed the elements of MMT with Tymoigne and Wray ( 2013 ) concluding that what MMT adds to old Keynesian economics is wrong. Similarly, Skousen ( 2020 ) investigated the macroeconomics textbook on MMT by Mitchell et al. ( 2019 ) concluding that MMT is dangerous as its policies may provoke runaway inflation, and that it is not required as countries can reduce unemployment substantially without applying MMT policies. Brady ( 2020 ) summarized five cornerstones of MMT concerning the sustainability of very high public debt and refuted them with results from old and contemporary economic literature. Coats ( 2019 ) studied MMTs free-borrowing hypothesis for governments and argued that this radical view was based on the critical assumption that the natural rate of interest is zero. Hartley ( 2020 ) found that MMT might be a political movement rather than an economic theory, as long as there is no empirical evidence for its propositions on government debt and inflation-free money creation. The MMT critique of Epstein ( 2019 , 2020 ) is related to the existing institutions that are responsible for monetary and fiscal policy. According to Epstein, this institutional setting and the functioning of modern financial markets may seriously limit the implementation of MMT’s policy recommendations. Kashama ( 2020 ) assessed MMT from the viewpoint of macroeconomic stabilization in the eurozone. His conclusion was that the policy assignment to the governments and the central bank, with the central bank responsible for price-level stability, should not be changed, in stark contrast to MMT. Compared to these papers, this short contribution relates to the theoretical foundation of MMT at a very fundamental level.

This paper most closely resembles Palley ( 2015b ). Palley provided a sophisticated theoretical analysis of MMT from a Keynesian viewpoint. He demonstrated very clearly the basic Keynesian approach of MMT and argued that nothing of relevance was added that would justify the term MMT. In contrast to Palley ( 2015b ), this paper takes MMT seriously in the sense that a simple version of MMT is used to prove that it is identical to the Keynesian cross model. In the model, MMT’s approach of financing government expenditures by money creation is applied, showing that MMT’s interpretation of money does not change anything. MMT does not present a new theory of money, but only accounting identities. Moreover, the fundamental flaw in MMT is a misreading of the equilibrium condition of the underlying macroeconomic system. Far reaching policy recommendations, such as financing large-scale social policy expenditures by public deficits or printing money, do not seem to be justified on the basis of MMT. Moreover, information in the Online Supplemental Appendix shows that even in MMT, ex post Ricardian equivalence must hold true. This implies that money is neutral in the sense that it does not eliminate or mitigate the fiscal burden of government expenditures.

Simplest MMT Model: SIM

The following presentation of MMT in the simplest version (SIM) is based on Godley and Lavoie ( 2012 , pp. 61–72). SIM is interpreted as the basic model of MMT. Moreover, all subsequent extensions of the model inherit the characteristics of SIM. The notation in this presentation is somewhat modified (without any content change) to make it easier to compare SIM with the simplest Keynesian model in the next section. The disposable income of households, \({Y}_{d}\) , is given by:

where W is wage, \({L}_{S}\) is labor supply, and T is tax payments of households. Note that firms are not modelled explicitly, as is quite usual in very simple macroeconomic models. Implicitly, firms employ labor services of households to produce goods and services and they pay wages to the households as remuneration of labor services.

SIM has two behavioral equations. The first one is the tax function, T , defined by the government:

where t is the tax rate of a proportional wage tax. The second behavioral equation is the consumption function, C , of households:

where \(\alpha ,\beta\) are coefficients and \({M}_{HH-1}\) is money stock of households from the previous period. The consumption function in Eq. ( 3 ) depends on the disposable income, with α as the marginal propensity to consume and β as the influence of the money stock households hold from previous periods.

Money is created by the government via the public budget deficit:

where \({M}_{G}({M}_{G-1})\) is money creation of the government in the current (previous) period and G is government expenditures for goods and services. Equation ( 4 ) can be understood as the monetization of debt (Protopapadakis and Siegel, 1986 ; Thornton 2010 ). Instead of I-owe-you’s (IOUs), the government buys goods and services by creating its own money, also called outside money (Wray 2014 ). Money is defined here as an accounting measure, or “as a two-sided balance sheet phenomenon” (Bell 2001 , p. 151). Therefore, it cannot be said whether it is an asset or only a numeraire (for a discussion of the latter, see Otaki 2012 ).

Households adjust their holding of money as follows:

i.e., the difference between disposable income and consumption is equal to the change in money holding. Obviously, the difference between disposable income and consumption must be equal to households’ savings, S (note that S is not included in SIM). National income is given by the production of consumption goods and public goods:

Note that Eq. ( 6 ) is an ex post identity. Therefore, it is neither right nor wrong. In addition, there are no investments. The proceeds are distributed to the factor of production, i.e., the labor services of households: \(Y=W\cdot {L}_{D} \underset{}{\Rightarrow } {L}_{D}=\frac{Y}{W}\) , where \({L}_{D}\) is labor services demand.

Since the money created by the government (money supply) must be equal to the money holding of households (money demand), the public budget deficit is equal to the change in the stock of money and, hence, savings:

Put differently, this means (not contained in the SIM presentation of Godley and Lavoie, 2012 ):

Equation ( 8 ) is the implication of a standard economic circular flow model with government, where \(S=I+(G-T)\) , if there are no investments (as is the case in SIM), i.e., \(I=0\) . Obviously, the equality of savings, money creation and public budget deficit is a consequence of the descriptive circular flow model of the economy. This demonstrates that no new theory of money is presented with SIM and, hence, MMT. Instead, Eqs. ( 6 , 7 , 8 ) are ex post identities.

In a (long-run) steady state equilibrium, government expenditures must be tax financed in order to avoid so-called Ponzi-games:

with Y* as the steady state equilibrium national income. Rearranging the terms in Eq. ( 9 ) yields:

Equation ( 10 ) is called fiscal stance. Godley and Lavoie ( 2012 , p. 72) emphasized the importance of the fiscal stance as follows: “It [i.e., G / t ] plays a fundamental role in all of our models with a government sector, since it determines GDP (i.e., gross domestic product) in the steady state.” In MMT, the expression G / t (government expenditures divided by the tax rate) is considered causal for the equilibrium national income, Y* . Even in a larger model with government money and portfolio choice (Godley and Lavoie, 2012 , p. 99), the steady state solution collapses to Eq. ( 10 ) if the average interest rate on all government liabilities is zero (Godley and Lavoie, 2012 , p. 115). A further implication (not mentioned) of SIM is again an ex post identity:

This implication is consistent with the circular flow model of the economy since there are no investments in SIM: \(I=0 \underset{}{\Rightarrow }S=G-T, G=T\underset{}{\Rightarrow }S=0\) .

To summarize, the simplest model containing the main elements of MMT is based on the descriptive circular flow model of an economy, combined with a tax function defined by the government, and a consumption function. However, the conclusion suggests that government expenditures (in combination with the income tax rate) causally determine the equilibrium national income. Footnote 1 To understand SIM better, it is compared with the simplest Keynesian model (KEYSIM) in the following.

SIM Versus the Keynesian Cross, KEYSIM

The Keynesian cross model, or KEYSIM, can be considered the simplest Keynesian model of an economy. It can be found in any introductory macroeconomics textbook (Beck and Prinz, 2018 , p. 145–156). The KEYSIM is also based on Eq. ( 6 ), i.e., that national income can be used for private consumption, C , or public expenditures for goods and services, \(G\; (Y=C+G)\) :

Moreover, the consumption function is given by:

i.e., consumption consists of an income-independent element, C 0 , and depends on disposable income, Y d , with α as the marginal propensity to consume. Disposable income is given by total income, Y , minus savings, S , and tax payments, T : \({Y}_{d}=Y-S-T\) , whereby the tax is again a proportional income tax:

Furthermore, in equilibrium, all government expenditures are financed via taxation so that \(G=T\) . Finally, since there are no investments, the circular flow model implies that savings are zero ( \(S=0\) ). Therefore, combining Eqs. ( 6 , 12 , 13 ) gives:

Solving Eq. ( 14 ) for the equilibrium national income, Y , yields:

Equation ( 15 ) deviates from Eq. ( 9 ) ( \(G=T=t\cdot {Y}^{*}=t\cdot W\cdot {L}^{*}\) ) that also determines the equilibrium value of government expenditures. According to Eq. ( 15 ), the value of government consumption is given by: \(G=t\cdot {Y}^{*}=t\cdot \frac{{C}_{0}}{(1-\alpha )(1-t)}\) . In SIM, Eq. ( 3 ) says \(C\left({Y}_{d},{M}_{HH-1}\right)=\alpha \cdot {Y}_{d}+\beta \cdot {M}_{HH-1}\) . For sake of simplicity, let

which is that part of consumption that is independent of current income. Note that the term \(\beta \cdot {M}_{HH-1}\) in the consumption function is the only innovation in SIM, in comparison to KEYSIM. Accordingly, Eq. ( 14 ) holds also in SIM:

The long-run steady state equilibrium national income with a balanced public budget reads according to Eq. ( 15 ). There is also no contradiction to the long-run steady state equilibrium of SIM in Eq. ( 10 ) ( \({Y}^{*}=\frac{G}{t}\) ) since this also implies in SIM:

which is identical to the value of government consumption in KEYSIM, as can be seen by multiplying Eq. ( 15 ) with the tax rate, t .

Hence, up to this point, SIM and KEYSIM are indistinguishable. However, the Keynesian cross is an oversimplification of the Keynesian model. In this paper, only the short run is considered. Extending the model requires the incorporation of price-wage adjustments with Philips-curves. In such an extended model, price-wage dynamics will lead back to the long-term equilibrium. In contrast, MMT models do not contain price-wage adjustments. It is unclear what role money would play in MMT concerning price-wage adjustments. In this respect, MMT cannot be compared with a Keynesian model as applied here.

In addition, even in a neoclassical world with fully flexible wages and prices, the equilibrium condition (that may be written as \({Y}^{*}=Y\) ) will hold. Nevertheless, in neoclassical theory, supply determines equilibrium output. Moreover, with fully flexible prices and wages, monetary policy determines nominal variables in equilibrium. Fiscal policy may change the composition of demand and the distribution of income as fiscal stabilization is not an issue. Hence, in effect, the above analysis is not only compatible with MMT and Keynesian theory, but also with neoclassical macroeconomic theory. Consequently, SIM (and MMT) is not wrong. Where then does MMT get it wrong?

Misreading the Equilibrium Condition

The key to understand MMT is reading the equilibrium result in Eq. ( 18 ). By simple algebra, this equation can be written as:

As an equation, it can be interpreted in several ways:

National income, Y* , is determined by the government via choosing expenditures, G , and tax rate, t .

National income, Y* , is determined by the income-independent part of consumption, \({C}_{0}=\beta {M}_{HH-1}\) , the marginal propensity to consume, α , and the tax rate, t .

National income, Y* , is the result of the aggregate demand in an economy.

The production side of national income, Y* , determines private and public consumption.

Aggregate production and aggregate demand are equal at the equilibrium national income of Y* .

All of these versions are of necessity correct, or at least not wrong, because there is no causality involved. Since both models share the same bases (i.e., the circular flow model of an economy, a tax function and a consumption function) and the same equilibrium condition (aggregate supply is equal to aggregate demand), they are indistinguishable. Moreover, it is clear that both models are of Keynesian origin because the supply side reacts passively to changes in aggregate demand. By assumption, aggregate demand determines (is causal for) national income.

The claim of MMT that government expenditures, financed by running a public deficit via the creation of money, determine (causally) national income constitutes a misreading of an equilibrium condition (i.e., reading the equation from right to left). However, an equation simply equates two sides of the equation and nothing else. The causality is externally added by the reader, as it were.

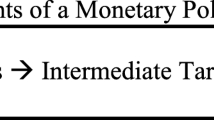

Figure 1 shows SIM in a circular flow diagram. According to MMT, government expenditures for goods and services, G , in combination with a public budget deficit financed by creation of additional money, Δ MG (i.e., that part of G not financed via taxation with the tax rate, t ), determines national income, Y* .

Fiscal stance and national income determination. Source: Own depiction

However, as Fig. 1 demonstrates, all causal explanations of Y* are circular. The model contains not one, but two decision making units: the government and households. Therefore, both are causal (in an interdependent way) for the size of national income. Moreover, the model is built on ex post identities (i.e., on accounting identities) as Fig. 1 demonstrates.

Another proposition of MMT can be clarified with Fig. 1 . According to MMT, it is neither taxes nor borrowing that finance public expenditures, but the creation of fiat money (Forstater 1999 , citing Lerner 1951 ; Bell 2000 ). In Fig. 1 , this corresponds with \(G=\Delta {M}_{G}\) . This implies that T = 0. However, even in SIM, the steady state equilibrium requires that the No-Ponzi-Game condition, G = T , holds true (Godley and Lavoie, 2012 , p. 71). In Fig. 1 , the circular flow between households and the government indicates the equivalence of taxes and fiat government money according to \(T=\Delta {M}_{G}\) . Insofar, taxation is a method to regulate the amount of money in the economic circuit (Tymoigne and Wray, 2013 ). However, this is only an ex post accounting identity. As indicated by Fritz Machlup, ex post identities are futile for policy conclusions:

“Macro-theorists have not always been careful and have repeatedly been misled into thinking they could deduce consequences from an ex post definition, for example, that they could deduce the effects of an increase in investment from the definitional equation Y = C + I. This is logically impossible, and therefore inadmissible in macro-theory and in micro-theory” (Machlup, 1963 , p. 120).

Furthermore, the misreading of the equilibrium condition of SIM is responsible for the policy recommendations. Equation ( 12 ) and all equations containing Y* are different versions of the same equilibrium condition (e.g., Eq. ( 15 )). Of course, static multipliers may be derived from Eq. ( 14 ). Since the basis of MMT is the old-school Keynesian cross model, changes in aggregate demand variables lead to certain static multipliers. In effect, that government expenditures may increase national income does not depend on a certain theory of money, but on the fact that such a model allows by assumption only demand-side effects. That is all one can say on fiscal policies in this model.

Figure 1 also sheds some light on the issue of inflation, which is not a problem according to MMT. Inflation only occurs when aggregate demand is larger than aggregate supply. If demand outstrips supply, the government can decrease money supply by increasing taxes. Figure 1 shows that there is no monetary theory in this model, no assumptions about the endogeneity of money supply, the role of excess reserves of the central bank, the role of the financial sector and people’s expectations concerning the effects of monetary policy. If, for example, people expect more inflation or taxes as a result of higher government debt, the simple results of the SIM may not hold.

Figure 1 also shows another flaw of MMT. It neglects the role of the foreign sector. MMT assumes that as long as a country does not borrow in a foreign currency, it cannot default. This is certainly true, but most countries do not have the exorbitant privilege (Eichengreen 2011 ) of issuing a reserve currency. They have no choice but to borrow in foreign currencies. This aspect of MMT may explain why MMT is more popular in the U.S. than in other countries. The propositions of MMT may cause serious financial instability in an open economy with flexible exchange rates as fixed exchange rates would impose a hard budget restraint on the government which would mean that the government could default on its debt.

MMT and Economic Policy

At first glance, it seems that MMT and the almost worldwide monetary policy called quantitative easing (QE) have much in common. In MMT as with QE, the central bank creates very large quantities of money, mainly by buying government securities in the secondary market. The similarity ends there. QE is designed as a temporary policy in order to stabilize economies which suffer from financial crises, such as that caused by a pandemic virus. QE is not and was never intended to finance government expenditures (Globerman 2020 ). Central banks will start to reduce the quantity of money after the crises by selling back government securities before they mature (Globerman 2020 ). Although QE means a certain degree of monetizing government debt, it remains a policy instrument of a politically independent central bank (Epstein 2019 ).

In contrast, in MMT the government finances public expenditures via money creation, with no intention to refinance them with taxes (Bell 2000 ). That is, monetization of the debt is forever. In this way, politicians control the creation of money and not politically independent central banks. Moreover, monetary policy explicitly finances government expenditures. Monetary policy is no longer monetary policy, but rather a combination of monetary and fiscal policy (Tymoigne 2016 ). As is recognized by serious proponents of MMT (Mitchell 2010a , 2010b ), such a policy can only last as long as there are spare capacities in an economy in the form of unemployed workers and underused production facilities. If capacity is fully used, additional money will create inflation. At this point, the government should increase taxes to avoid inflation by restricting private resource use via consumption and investment. In contrast to QE, the creation of money (or, equivalently, the monetization of government debt) in MMT is an instrument to finance public expenditures. Taxes serve as instruments to reduce private consumption and investment, in order to avoid inflation. However, there are also new ideas to employ taxes for financing social policy and even a Green New Deal (Baker and Murphy, 2020 ).

The differences between QE and MMT demonstrate that MMT has different political intentions. Monetary policy is employed to finance the state in order to release taxation from its usual function of financing public goods. Another policy recommendation underlines this intention, the so-called job guarantee (JG) (Mosler 1998 ; Parguez 2008 ; Tcherneva 2020 ). JG “is at the centerpiece of MMT reasoning. It is neither an emergency policy nor a substitute for private employment, but would become a permanent complement to private sector employment” (Mitchell et al., 2019 , p. 295). JG is considered as an automatic stabilizer in MMT (Mitchell et al., 2019 , p. 303) and would be financed by money creation, i.e., public debt. Although it has some resemblance to Keynesian deficit-financed stabilization policies in a recession, guaranteeing jobs that produce goods and services at the minimum wage is outside the Keynesian concept. In effect, it is labor market policies paid for by money creation. However, that JG policy may become inflationary is denied (Mitchell et al., 2019 , p. 304) because the government is “buying labour off the bottom” (Mitchell et al., 2019 , p. 304), i.e., that minimum-wage JG-employment has no effect on the structure of wages. Moreover, MMT ignores all microeconomic problems of JG policy.

This brief look at the differences between QE and MMT demonstrates that the monetary concept of MMT has almost nothing in common with QE. The MMT policy intentions promise a kind of new brave world that is economically stable, socially more equal and environmentally green. However, the economics of MMT are unclear at best. Who will pay for this world remains an unanswered question. As MMT seems to suggest, it is a free lunch.

As a matter of fact, someone has to pay sometime for the economic, social and environmental benefits of MMT. Since taxes are excluded and public deficits are monetized, the inflation tax is financially the last resort, unless it is avoided by taxes. Hence, the usual result is still valid. The usage of real resources must be paid for, either through ordinary taxes, the inflation tax or financial repression.

This leads to the final point of the analysis as MMT neglects the political aspects of recommended policies. MMT hands over responsibility for fiscal and monetary policy to politicians seeking re-election, hoping that these politicians will act responsibly. Therefore, MMTs over-simplistic analysis understates the risks of the policy implications (Palley 2015b ). For policy recommendations, larger sets of behavior functions are required that show how households and firms react and adjust to such policies (Machlup 1963 ). Mankiw ( 1988 ), Reinhorn ( 1998 ) and Otaki ( 2007 ) incorporate imperfect competition into the Keynesian cross model. Therefore, one can say that the policy implications and recommendations of MMT are neither theoretically well-founded nor politically justified (for further critical reviews of MMT, see e.g. Brady 2020 ; Newman 2020 ; Skousen 2020 ).

The main contribution of this paper to the literature on MMT concerns the theoretical foundation of MMT. In a simple macroeconomic model, SIM, it is shown that MMT is indistinguishable from the Keynesian cross model, as well as neoclassical macroeconomic models. Demonstrating this with models is a necessary step to demystifying and debunking MMT as an economic theory.

There are few cases where many economists, Keynesian or Austrian, agree, but the rejection of MMT’s hypotheses is one of them (Brady 2020 ; Skousen 2020 ). In the current paper, simple macroeconomic models were applied to show that there is almost nothing new in MMT. The important insight is that the fundamental role of the so-called fiscal stance in MMT (i.e., equilibrium national income is equal to government expenditures divided by the tax rate on income, \({Y}^{*}=\frac{G}{t}\) ) is a relationship that holds trivially true in all Keynesian cross models and even in neoclassical macroeconomic models. It is neither specific to MMT nor does it follow from a new theory of money.

In fact, the fiscal stance is the consequence of the ex post identities of the economic circuit, an aggregate consumption function of private households and the non-Ponzi-game condition for the state. In the SIM model, the latter condition renders money meaningless because it is by definition an accounting identity, and because output used by the state can no longer be consumed (or saved) by private households. Ultimately, government expenditures are financed by taxes, whatever they are called. Moreover, it is not possible to say that the government can determine equilibrium national income. This statement is a misunderstanding of the fiscal stance that is an equilibrium condition, without any causality whatsoever.

Furthermore, MMT does not provide a theory of money. Instead, “money is a creation of the state” is the simple statement on which money is based (which is the topic of Knapp’s “The State Theory of Money”, published in German in 1905 ; MMT theorists quote this origin). However, in comparison to the conventional theory of money, this is a big step backwards. Last but not least, the far-reaching policy recommendations of MMT are not justified by economic theory. They are highly exaggerated since no further behavioral assumptions for households or firms are formulated that could show how the respective economic entities react and adjust to the recommended policies.

The Online Supplemental Appendix shows in a two-period variant of SIM that in MMT ex post Ricardian equivalence must hold true. The reason is that government expenditures use real economic resources that must be transferred from private households to the state. The instrument to carry out this transfer is called taxes.

Arestis, P. (1996). Post-Keynesian economics: Towards coherence. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 20 (1), 111–135.

Article Google Scholar

Baker, A., & Murphy, R. (2020). Modern monetary theory and the changing role of tax in society. Social Policy & Society, 19 (3), 454–469.

Beck, H., & Prinz, A. (2018). Makroökonomie für Dummies [Macroeconomics for Dummies] . Weinheim: Wiley.

Google Scholar

Bell, S. (2000). Do taxes and bonds finance government spending? Journal of Economic Issues, 34 (3), 603–620.

Bell, S. (2001). The role of the state and the hierarchy of money. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25 (2), 149–163.

Brady, G. L. (2020). Modern monetary theory: Some additional dimensions. Atlantic Economic Journal, 48 (1), 1–9.

Coats, W. (2019). Modern monetary theory: A critique. Cato Journal, 39 (3), 563–576.

Council of Economic Advisers. (2016). Active labor market policies: Theory and evidence for what works . Issue Brief December 2016. Available at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20161220_active_labor_market_policies_issue_brief_cea.pdf . Accessed March 25 2021.

Dixon, H. D., & Rankin, N. (Eds.). (1995). The new macroeconomics: Imperfect markets and policy effectiveness . Cambridge, New York and Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Eichengreen, B. (2011). Exorbitant privilege: The rise and fall of the dollar and the future of the international monetary system . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Epstein, G. A. (2019). What’s wrong with modern money theory? A policy critique . Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Epstein, G. (2020). The empirical and institutional limits of modern money theory. Review of Radical Political Economics, 52 (4), 772–780.

Forstater, M. (1999). Functional finance and full employment: Lessons from Lerner for today. Journal of Economic Issues, 33 (2), 475–485.

Globerman, S. (2020). Modern monetary theory, Part 4: MMT and quantitative easing. Available at: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/blogs/modern-monetary-theory-part-4-mmt-and-quantitative-easing . Accessed January 12 2021.

Godley, W., & Lavoie, M. (2012). Monetary economics (2nd ed.). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hartley, J. (2020). The weakness of modern monetary theory. National Affairs, Fall, 2020 , 70–82.

Kashama, M. K. (2020). An assessment of modern monetary theory. Belgische Nationalbank, NBB Economic Review, September 2020 , 1–14.

Knapp, G. F. (1905). Staatliche Theorie des Geldes. München/Leipzig: Duncker und Humblodt. (English translation: The state theory of money . London: Macmillan, 1924).

Lavoie, M. (2009). Introduction to Post-Keynesian economics . Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lerner, A. P. (1943). Functional finance and the federal debt. Social Research, 10 (1), 38–51.

Lerner, A. P. (1944). The economics of control . New York: Macmillan.

Lerner, A. P. (1951). The economics of employment . New York: McGraw Hill.

Machlup, F. (1963). Micro- and macro-economics: Contested boundaries and claims of superiority (pp. 97–144). In: Miller, M. H. (Ed.), Essays on Economic Semantics by Fritz Machlup . Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Mankiw, N. G. (1988). Imperfect competition and the Keynesian cross. Economics Letters, 26 (1), 7–13.

Mitchell, W. F. (2010a), Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 1 . Available at: http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=10554 . Accessed January 12 2021.

Mitchell, W. F. (2010b), Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 2. Available at: http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=13035 . Accessed January 12 2021.

Mitchell, W., Wray, R. A., & Watts, M. (2019). Macroeconomics . London: Red Globe Press.

Mosler, W. (1998). Full employment and price stability. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 20 (2), 167–182.

Newman, P. (2020). Modern monetary theory: An Austrian interpretation of recrudescent Keynesianism. Atlantic Economic Journal, 48 (1), 23–31.

Nikiforos, M., & Zezza, G. (2017). Stock-flow consistent macroeconomics models: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 31 (5), 1204–1239.

Otaki, M. (2007). The dynamically extended Keynesian cross and the welfare improving fiscal policy. Economics Letters, 96 (1), 23–29.

Otaki, M. (2012). The role of money: Credible asset or numeraire? Theoretical Economics Letters, 2 (2), 180–182.

Palley, T. I. (2015a). The critics of modern money theory (MMT) are right. Review of Political Economy, 27 (1), 45–61.

Palley, T. I. (2015b). Money, fiscal policy, and interest rates: A critique of modern monetary theory. Review of Political Economy, 27 (1), 1–23.

Parguez, A. (2008). Money creation, employment and economic stability: The monetary theory of unemployment and inflation. Panoeconomicus, 55 (1), 39–67.

Protopapadakis, A., & Siegel, J. J. (1986). Are government deficits monetized? Some international evidence. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Business Review , November/December , 13–22.

Reinhorn, L. J. (1998). Imperfect competition, the Keynesian cross, and optimal fiscal policy. Economics Letters, 58 (3), 331–337.

Skousen, M. (2020). There’s much ruin in a nation: An analysis of modern monetary theory. Atlantic Economic Journal, 48 (1), 11–21.

Tcherneva, P. R. (2020). The case for a job guarantee. Cambridge, UK, and Medford, MA, USA: Polity Press.

Thornton, D. L. (2010). Monetizing the debt. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Economic Synopses, No., 14 , 1–2.

Tymoigne, E. (2016). Government monetary and fiscal operations: Generalising the endogenous money approach. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 40 (5), 1317–1332.

Tymoigne, E., & Wray, L. R. (2013). Modern money theory 101: A reply to critics . Levy Economics Institute, Working Paper No. 778. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2348704 . Accessed January 19 2021.

Wray, L. R. (2014). Outside money: The advantages owning the magic porridge pot . Economics Working Paper Archive wp_821, Levy Economics Institute. Available at: http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_821.pdf . Accessed January 19 2021.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank an anonymous referee for very helpful comments and recommendations, including pointing out comparisons with Keynesian and neoclassical models. All errors are ours.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Public Economics, University of Muenster, Wilmergasse 6-8, 48143, Muenster, Germany

Aloys L. Prinz

University of Applied Sciences Pforzheim, Tiefenbronner Straße 65, 75175, Pforzheim, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Aloys L. Prinz .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 20 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Prinz, A.L., Beck, H. Modern Monetary Theory: A Solid Theoretical Foundation of Economic Policy?. Atl Econ J 49 , 173–186 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-021-09713-6

Download citation

Accepted : 04 May 2021

Published : 25 May 2021