Work Culture In Germany: Characteristics, Ethics & Differences

Discover the ins and outs of work culture in Germany, including its 10 unique characteristics and differences from other countries.

Pansy Thakuria

Read more posts by this author.

Work culture in Germany is deeply rooted in efficiency and precision, much like the smooth-running Autobahn . Punctuality is highly valued, and Germans take pride in punctuality for work commitments and appointments. This emphasis on timeliness reflects their dedication to professionalism and respect for others' time.

In this blog, we uncover key insights into the work culture of Germany that emphasizes teamwork, commitment to excellence, innovation, and creativity.

Here’s what we’ll learn here:

- What is German work culture Like?

- What are the top 5 German work ethics?

- German companies with the best work culture

- How is the work culture in Germany different from others?

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Is The German Work Culture Like: 10 Characteristics

German work culture revolves around a structured and well-organized approach. Punctuality is valued in German workplaces, and being on time is seen as a sign of respect and professionalism.

The concept of " Ordnung " (order) is ingrained in their work practices, where everything is planned and executed. Discipline is another cornerstone of the German work ethic, promoting efficiency and consistency.

In the German business work environment, setting clear priorities is vital. Here are the 10 important aspects of German Work Culture.

1. Work-Life Balance

Germany ranks 16th out of 41 countries for work-life balance according to the OECD Better Life Index .

One of the most significant aspects of German work culture is maintaining a healthy work-life balance. Germans are dedicated professionals who believe in giving their best during working hours while ensuring personal time is well-respected.

Employers in Germany understand the importance of rest and leisure in maintaining a motivated and productive workforce. This approach contributes to reduced stress levels and increased job satisfaction among employees.

2. Communication Style

Germans are known for their direct and straightforward communication style. Honesty and clarity are highly valued in the workplace. Meetings are well-structured, and decisions are based on well-researched facts rather than emotions.

While this approach may seem formal to some, it streamlines processes, minimizes misunderstandings, and ensures efficient problem-solving.

3. Punctuality and Time Management

Punctuality is a hallmark of German work culture. Being on time for meetings, appointments, and deadlines shows respect and reflects professionalism. Germans strongly emphasize time management, ensuring tasks are completed promptly and efficiently.

Working Hours: Germany's stringent labor laws enforce regulations on working hours, leading to a maximum of 48 hours per week. Overtime work is generally compensated or given time off in lieu.

4. Teamwork and Collaboration

Collaboration is at the core of German work culture. Teams work cohesively, sharing ideas and responsibilities to achieve common goals. A flat organizational structure allows for open communication and fosters an environment where everyone's input is valued.

"Kaffeepause" (Coffee Break): Germans take their coffee breaks seriously and often use this time to socialize and build camaraderie with colleagues. It is seen as a vital aspect of workplace culture and employee well-being.

5. Emphasis on Quality

German work culture is synonymous with quality craftsmanship. Whether manufacturing, engineering, or services, Germans take pride in delivering top-notch products and services. This focus on quality has earned Germany a reputation for excellence worldwide.

6. Appreciation for Hard Work

Hard work and dedication are highly appreciated in German workplaces. Efforts and achievements are recognized, encouraging employees to perform at their best. Recognizing and rewarding hard work also promotes a positive and motivating work atmosphere.

7. Employee Welfare and Benefits

German companies prioritize the well-being of their employees. Work culture in Germany focuses on generous employee benefits such as

- Parental leave

- Retirement plans

- Social security

These benefits increase job satisfaction and employee retention for German workers.

8. Hierarchical Structure and Respect

German companies often adhere to a hierarchical structure, where clear authority lines are established. However, this structure is accompanied by a culture of respect for individuals at all levels. Superiors and subordinates treat each other with respect and professionalism.

9. Innovation and Creativity

Despite the reputation for precision and efficiency, the German work culture encourages innovation and creativity. The country has a thriving startup scene, and many companies actively promote new ideas and concepts.

"Feierabend" Culture: Germans have a unique concept called "Feierabend ," which refers to the time after work when individuals fully disconnect from work-related matters. It is a cherished time to relax, spend time with family, and pursue personal interests.

10. Influence of German History and Culture

The nation's history and cultural values undoubtedly influence German work culture. Concepts like discipline, responsibility, and the pursuit of excellence have deep roots in German society.

What are the top 5 German Work Ethics?

There are five major work ethics that Germans follow during their professional life:

Reliability: Germans are known for their reliability and dependability in the workplace. Meeting deadlines and commitments is of utmost importance.

Precision: Attention to detail is valued in German work culture. Precision is expected in all aspects of work, leading to a high-quality standard.

Honesty and Integrity: German professionals focus on honesty and integrity. Transparency in communication and ethical behavior is integral to their work ethics.

Thoroughness: Germans believe in thorough planning and execution. They leave no room for ambiguity and aim for comprehensive solutions.

Respect for Work-Life Balance: Although hard work is essential, Germans also respect the boundaries between personal and professional life. Maintaining a healthy work-life balance is encouraged.

German Companies With The Best Work Culture

German organizations exemplify jobs with good company cultures , providing their employees with an enriching experience. Companies focusing on their employees' well-being, growth, and satisfaction tend to foster a positive work environment, increasing productivity and innovation.

Many German companies offer an excellent work culture. Some of the most renowned ones include

BMW's commitment to employee well-being and development sets it apart as a leader in creating an exceptional work culture. With a focus on diversity and inclusivity, BMW fosters an environment that values each employee's unique contributions.

Siemens is renowned for its employee-centric approach, offering flexible work arrangements and opportunities for growth. By promoting a culture of innovation and collaboration, Siemens ensures its employees thrive.

SAP's work culture revolves around transparency and open communication. The company's emphasis on employee empowerment and recognition is crucial in fostering a positive and motivated workforce.

Bosch places a strong emphasis on employee development and learning opportunities. Bosch encourages its employees to reach their full potential through various training programs and career advancement initiatives.

How is the Work Culture in Germany Different from Others?

Germany is located in Central Europe and boasts a developed economy. The German work culture reflects a sense of equality and inclusivity. Hierarchical barriers are less pronounced, and open communication is encouraged across all levels of an organization.

The work environment in Germany is often perceived as meritocratic, meaning that career progression is based on performance and qualifications rather than favoritism.

However, the work culture differs from other countries in several ways:

German vs. British Work Culture

In British work culture, the average qualification is often a university degree. Germans value punctuality, efficiency, and precision in their workplaces, emphasizing a well-structured environment. On the other hand, British work culture values teamwork, adaptability, and open communication, fostering a friendly and inclusive work atmosphere.

German vs. American Work Culture

In American work culture , the average qualification is a mix of high school diplomas and bachelor's degrees. Germans focus on work-life balance, quality work, and professional development , focusing on long-term success. In contrast, the American work culture celebrates innovation, risk-taking, and individual achievements, encouraging a competitive yet rewarding workplace environment.

German vs. Japanese Work Culture

In Japan, the average qualification often includes higher education degrees. Germans value precision, discipline, and organization, aiming for efficiency and reliability. Japanese work culture emphasizes respect for hierarchy, teamwork, and dedication to the company, creating a cohesive and harmonious work setting.

Curious about work cultures in other parts of the world?

Discover unique workplace norms, etiquettes, and dynamics from various countries.

Work Culture in Singapore

Work Culture in America

Work Culture in France

Work Culture in Japan

Zusammenfasst (Summing Up)

Unraveling Germany's work culture reveals a surprisingly adaptable environment. With research, anyone can harmonize with its culture and rhythm. Embrace work-life balance, navigate hierarchies through open communication, and infuse passion into your efforts.

Germany's culture is a melody of efficiency and purpose – with a little insight, you'll find yourself dancing to its tune effortlessly.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. is adapting to the german work culture as a foreign employee challenging.

A: While there might be some initial adjustments, most foreigners appreciate German work culture's structure and organization. Being open-minded and willing to adapt will ease the transition.

2. What are the typical working hours in Germany?

A: The standard working hours in Germany are usually 40 hours per week, with an average of 8 hours a day.

3. How important is the German language for working in Germany?

A: While English is widely spoken in business, learning German can significantly enhance your work experience and cultural integration.

4. Are overtime hours common in German companies?

A: Overtime hours are generally not as common in German companies compared to some other countries. There is a focus on productivity during regular working hours. Furthermore, they avoid causing overloaded work for employees.

5. How do Germans handle conflicts in the workplace?

A: Germans prefer direct communication to resolve conflicts. Addressing issues openly and professionally is the most effective way to find solutions.

6. Are there cultural differences in gift-giving in the workplace?

A: Yes, gift-giving in the workplace is not as common in Germany as in some other cultures. If you wish to offer a gift, it's best to keep it modest and professional.

7. Is it acceptable to question authority in German workplaces?

A: While open discussions are encouraged, questioning authority directly may not be as common. Respectful communication is essential, even when expressing differing opinions.

8. What are the main public holidays in Germany?

A: Some of the main public holidays in Germany include Christmas, Easter, New Year's Day, and Unity Day (Tag der Deutschen Einheit).

9. How do Germans view work-related socializing and team-building activities?

A: Work-related socializing and team-building activities are valued in German work culture as they foster team cohesion and strengthen relationships among colleagues.

10. Is remote work widely accepted in German companies?

A: Remote work gained popularity in Germany, especially after recent global events. Many companies now offer flexible work arrangements to their employees.

This article has been written by Pansy Thakuria . She works as a Content Marketing Specialist at Vantage Lens . Her areas of interest include marketing, mental well-being, travel, and digital tech. When she’s not writing, she’s usually planning trips to remote locations and stalking animals on social media.

Join for job search assistance, workplace tips, career guidance, and much more

How the Language You Speak Influences the Way You Think

The relationship between language and thought is far from straightforward..

Posted August 8, 2018 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

[Article revised on 24 November 2020.]

Time heaved a gentle sigh as the wind swept through the willows.

Communication does not require language, and many animals communicate effectively by other means. However, language is closely associated with symbolism, and so with conceptual thought, problem solving, and creativity . These unique assets make us by far the most adaptable of all animals and enable us to engage in highly abstract pursuits such as philosophy , art, and science that define us as human beings.

Here’s a thought experiment. Imagine what it would be like to live without language—not without the ability to speak, but without language itself. Given the choice, would you rather lose the faculty of sight or the faculty of language? This is probably the first time that you have faced this question: The faculty of language is so fundamental to what it means to be human that, unlike the faculty of sight, we take it completely for granted. ‘Monkeys’ quipped Kenneth Grahame, ‘very sensibly refrain from speech, lest they should be set to earn their livings.’

If rhetoric, the beauty of language, can so bend us, how about language itself? In other words, how does the language you speak influence the way you think? The ostensible purpose of language is to transmit thoughts from one mind to another. Language represents thought, that’s for sure, but does it also determine thought?

Wittgenstein famously wrote that ‘the limits of my language stand for the limits of my world’. Taken at face value, that seems too strong a claim. There are over 7,000 languages in the world—with, by some estimates, one dying out every two weeks or so. The number of basic colour terms varies quite considerably from one language to another. Dani, spoken in New Guinea, and Bassa, spoken in Liberia and Sierra Leone, each have no more than two colour terms, one for dark/cool colours and the other for light/warm colours. But, obviously, speakers of Dani and Bassa are able to perceive and think about more than just two colours.

More subtly, there is no English equivalent for the German word Sehnsucht , which denotes dissatisfaction with reality and yearning for a richer, ‘realer’ ideal. But despite lacking the word, the American poet Walt Whitman (d. 1892) was able, very successfully, to conjure both the concept and the emotion : Is it a dream? Nay, but the lack of it the dream, And, failing it, life’s lore and wealth a dream, And all the world a dream.

The English language has a word for children who have lost their parents (‘orphan’), and a word for people who have lost their spouse (‘widow’ or ‘widower’), but no word for parents who have lost a child. This may mean that parents who have lost a child are less likely to enter our minds, but not that they cannot enter our minds or that we cannot conceive of them. We often think about or remember things that cannot be put into words, such as the smell and taste of a mango, the dawn chorus of the birds, or the contours of a lover’s face or other part of their anatomy. Animals and pre-linguistic babies surely have thoughts, even though they have no language.

If language does not determine thought, how, if at all, does it interact with thought? Russian, Greek, and many other languages have two words for blue, one for lighter shades and the other for darker shades— goluboy and siniy in Russian, and ghalazio and ble in Greek. A study found that, compared to English speakers, Russian speakers were quicker to discriminate between shades of goluboy and siniy , but not shades of goluboy or shades of siniy . Conversely, another study found that Greek speakers who had lived in the UK for a long time see ghalazio and ble as more similar than Greek speakers living in Greece. By creating categories, by carving up the world, language supports and enhances cognition .

In contrast to modern Greek, Ancient Greek, in common with many ancient languages, has no specific word for blue, leaving Homer to speak of ‘the wine-dark sea’. But the Ancient Greeks did have several words for 'love', including philia , eros , storge , and agape , each one referring to a different type or concept of love, respectively, friendship , sexual love, familial love, and universal or charitable love. This means that the Ancient Greeks could speak more precisely about love, but does it also mean that they could think more precisely about love, and, as a result, lead more fulfilled love lives? Or perhaps they had more words for love because they led more fulfilled love lives in the first place, or, more prosaically, because their culture and society placed more emphasis on the different bonds that can exist between people, and on the various duties and expectations that attend, or attended, to those bonds.

Philosophers and academics sometimes make up words to help them talk and think about an issue. In the Phædrus , Plato coined the word psychagogia , the art of leading souls, while discussing rhetoric—which, it turns out, is another word that he invented. Every field of human endeavour invariably evolves its own specialized jargon. There seems to be an important relationship between language and thought: I often speak—or write, as I am doing right now—to define or refine my thinking on a particular topic, and language is the scaffolding by which I arrive at my more subtle or syncretic thoughts.

While we’re talking dead languages, it may come as a surprise that Latin has no direct translations for ‘yes’ and ‘no’. Instead, one either echoes the verb in the question (in affirmative or negative) or expresses one’s feelings about the truth value of the proposition with adverbs such as certe , fortasse , nimirum , plane , vero , etiam , sane , minime … This may have led to more nuanced thinking, as well as greater interpersonal engagement, though it must have been a nightmare for teens—if they even had teens in those days.

As I argue in my new book, Hypersanity: Thinking Beyond Thinking , much of the particularity of a language is extra-lexical, built into the syntax and grammar of the language and virtually invisible to native speakers. English, for instance, restricts the use of the present perfect tense (‘has been’, ‘has read’) to subjects who are still alive, marking a sharp grammatical divide between the living and the dead, and, by extension, between life and death. But of course, as an English speaker, you already knew that, or at least subconsciously. Language is full of built-in assumptions and prejudices of this kind. Here’s another, more substantial example. When describing accidental events, English speakers tend to emphasize the agent (‘I fired the gun’) more than, say, speakers of Spanish or Japanese, who prefer to omit the agent (‘the gun went off’). One study found that, as a result, English speakers are more likely to remember the agents of accidental events—and, I surmise, to attach blame.

Some languages seem more egocentric than others. Many languages forgo the explicit use of the personal pronoun, which is instead built into the verb. For example, ‘I want’ in Spanish is simply quiero . English in contrast requires the explicit use of the personal pronoun in all cases, as does French. What’s more, French speakers often double up on the first-person personal pronoun, as in Moi, je pense que… [Me, I think that] with the stress on the moi . Sometimes, they also redouble on other personal pronouns, Et toi, qu’en penses-tu? [And you, what do you think about it?]. But redoubling on the first-person personal pronoun is much more common: Bon aller, moi j’en ai marre [Whatever, I’m fed up me]. This redoubling, this pleonasm, is more a feature of the spoken than the written word, and, depending on the context, can serve to emphasize or simply acknowledge a difference of opinion. Equivalent forms in English are more strained and recondite, and less commonly used, for example, ‘Well, as for me, I think that…’ The redoubling, in French, on the first-person personal pronoun seems to inject drama into a conversation, as though the speaker were acting out her own part, or playing up her difference and separateness.

In English, verbs express tense, that is, the time relative to the moment of speaking. In Turkish, they also express the source of the information (evidentiality), that is, whether the information has been acquired directly through sense perception, or only indirectly by testimony or inference. In Russian, verbs include information about completion, with (to simplify a bit) the perfective aspect used for completed actions and the imperfective aspect for ongoing or habitual actions. Spanish, on the other hand, emphasizes modes of being, with two verbs for ‘to be’— ser , to indicate permanent or lasting attributes, and estar , to indicate temporary states and locations. Like many languages, Spanish has more than one mode of second-person address: tú for intimates and social inferiors, and usted for strangers and social superiors, equivalent to tu and vous in French, and tu and lei in Italian. There used to be a similar distinction in English, with ‘thou’ used to express intimacy , familiarity, or downright rudeness—but because it is archaic, many people now think of it as more formal than ‘you’: Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate… It stands to reason that, compared to English speakers, Turkish speakers have to pay more attention to evidentiality, Russian speakers to completion, and Spanish speakers to modes of being and social relations. In the words of the linguist Roman Jakobson (d. 1982), ‘Languages differ essentially in what they must convey and not in what they may convey.’

In many languages, nouns are divided into masculine and feminine. In German, there is a third, neutral class of nouns. In Dyribal, an Aboriginal language, there are four noun classes, including one for women, water, fire, violence, and exceptional animals—or, as George Lakoff put it, ‘women, fire, and dangerous things’. Researchers asked German speakers and Spanish speakers to describe objects with opposite gender assignments in German and Spanish and found that their descriptions conformed to gender stereotypes, even when the testing took place in English. For example, teutophones tended to describe bridges (feminine in German, die Brücke ) as beautiful, elegant, fragile, peaceful, pretty, and slender, whereas hispanophones tended to describe bridges (masculine in Spanish, el puente ) as big, dangerous, long, strong, sturdy, and towering.

Another study looking at the personification in art of abstract concepts such as love, justice, and time found that, in 78% of cases, the gender of the concept in the artist’s language predicted the gender of the personification, and that this pattern held even for uncommon allegories such as geometry, necessity, and silence. Compared to a French or Spanish artist, a German artist is far more likely to paint death [ der Tod , la mort , la muerte ] or victory [ der Sieg , la victoire , la victoria ] as a man—though all artists, or at least all European artists, tend to paint death in skeletal form. So grammar, it seems, can directly and radically influence thought, perception, and action.

It is often said that, by de-emphasizing them, language perpetuates biases against women. For example, many writers in English continue to use ‘mankind’ to talk about humankind, and ‘he’ for ‘he or she’. Similarly, many languages use masculine plural pronouns to refer to groups of people with at least one man. If 100 women turn up with a baby in a pram, and that baby happens to have a penis, French grammar dictates the use of the masculine plural ils: ils sont arrivés , ‘they have arrived’.

Language changes as attitudes change, and sometimes politicians, pressure groups, and others attempt to change the language to change the attitudes—but, on the whole, language, or at least grammar, serves to preserve the status quo, to crystallize and perpetuate the order and culture that gave rise to it.

Language is also made up of all sorts of metaphors. In English and Swedish, people tend to speak of time in terms of distance: ‘I won’t be long’; ‘let’s look at the weather for the week ahead’; ‘his drinking finally caught up with him’. But in Spanish or Greek, people tend to speak of time in terms of size or volume—for example, in Spanish, hacemos una pequeña pausa [let’s have a small break] rather than corta pausa [short break]. More generally, mucho tiempo [much time] is preferred to largo tiempo [long time], and, in Greek, poli ora to makry kroniko diastima . And guess what… According to a study of bilingual Spanish-Swedish speakers, the language used to estimate the duration of events alters the speaker’s perception of the relative passage of time.

But all in all, with a few exceptions, European languages, or even Indo-European languages, do not differ dramatically from one another. In contrast, to talk about space, speakers of Kuuk Thaayorre, an Aboriginal language, use 16 words for absolute cardinal directions instead of relative references such as ‘right in front of you’, ‘to the right’, and ‘over there’. As a result, even their children are always aware of the exact direction in which they are facing. When asked to arrange a sequence of picture cards in temporal order, English speakers arrange the cards from left to right, whereas Hebrew or Arabic speakers tend to arrange them from right to left. But speakers of Kuuk Thaayorre consistently arrange them from east to west, which is left to right if they are facing south, and right to left if they are facing north. Thinking differently about space, they seem to think differently about time as well.

Language may not determine thought, but it focuses perception and attention on particular aspects of reality, structures and thereby enhances cognitive processes, and even to some extent regulates social relationships. Our language reflects and at the same time shapes our thoughts and, ultimately, our culture, which in turn shapes our thoughts and language. There is no equivalent in English of the Portuguese word saudade , which refers to the love and longing for someone or something that has been lost and may never be regained. The rise of saudade coincided with the decline of Portugal and the yen for its imperial heyday, a yen so strong and so bitter as to have written itself into the national anthem: Levantai hoje de novo o esplendor de Portugal [Let us once again lift up the splendour of Portugal]. The three strands of language, thought, and culture are so tightly woven that they cannot be prised apart.

It has been said that when an old man dies, a library burns to the ground. But when a language dies, it is a whole world that crumbles into the sea.

See my related article, Beyond Words: The Benefits of Being Bilingual.

Winawer J et al (2007): Russian Blues Reveal Effects of Language on Color Discrimination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104(19):7780-5.

Fausey CM et al. (2010): Constructing Agency: The Role of Language. Front Psychol 1:162.

Boroditsky L et al. (2003): Sex, Syntax, and Semantics. In Language in Mind: Advances in the Study of Language and Cognition, ed. Genter D & Goldin-Meadow S, pp. 61-80. Cambridge University Press.

Segel E & Boroditsky L (2010): Grammar in Art. Front Psychol. 1:244.

Bylund E & Athanasopoulos P (2017): The Whorfian Time Warp: Representing Duration Through the Language Hourglass. J Exp Psychol Gen. 146(7):911-916.

Gaby A (2012): The Thaayorre Think of Time Like They Talk of Space. Front Psychol 3:300.

Neel Burton, M.D. , is a psychiatrist, philosopher, and writer who lives and teaches in Oxford, England.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Navigating German Work Culture

- June 16, 2023

Share This Post

Table of contents.

Work culture plays a crucial role in shaping the professional environment in Germany. It encompasses the shared values, attitudes, and behaviors that influence how work is conducted and how professionals interact with one another. Understanding and adapting to the German work culture is essential for individuals and businesses operating in the country to establish successful relationships and achieve their goals.

Germany boasts one of the largest and strongest economies globally , making it an attractive destination for professionals and businesses alike. Its influential position in various industries, including automotive, engineering, and technology, further underscores the significance of understanding the working culture in Germany to thrive in this competitive landscape.

Definition and Components of Work Culture

Work culture and its significance in a professional environment.

Work culture refers to the shared values, norms, and practices that shape the behavior and interactions of individuals within a workplace. It sets the tone for communication, decision-making, and overall productivity. Understanding work culture is vital because it affects how professionals collaborate, make decisions, and achieve their objectives.

Key components that shape work culture in Germany

Punctuality and time management.

In German work culture, punctuality is highly valued. Being on time for meetings, appointments, and deadlines is considered a sign of respect for others’ time and a commitment to professionalism. Germans place great importance on planning and organization, and they expect colleagues and business partners to adhere to agreed-upon schedules. Being punctual demonstrates reliability and efficiency, which are highly regarded traits in the German work environment.

Hierarchical Structure and Respect for Authority

German organizations typically have a well-defined hierarchical structure . Decision-making power is often concentrated at the top, with clear lines of authority and responsibility. Respect for authority is deeply ingrained in German work culture, and employees are expected to follow the established chain of command. Managers and supervisors are respected for their expertise and experience, and their decisions are generally followed without question. This hierarchical structure provides clarity and direction within organizations.

Work-Life Balance

Work-life balance is a key aspect of German work culture. Germans believe in maintaining a healthy equilibrium between work and personal life. They value leisure time, family, and personal interests and encourage employees to prioritize their well-being. Germans typically work their designated hours and strive to complete tasks within regular working hours, avoiding excessive overtime. This approach to work-life balance contributes to employee satisfaction, well-being, and overall productivity.

Teamwork and Collaboration

Collaboration and teamwork are highly valued in German work culture. Professionals are expected to work effectively in teams, share knowledge, and contribute to collective goals. Open communication, active participation, and mutual support are encouraged. Germans appreciate the input and diverse perspectives of team members, as it fosters innovation and problem-solving. Working collaboratively helps build strong relationships and facilitates the achievement of common objectives.

Efficiency and Productivity

Efficiency and productivity are core principles in German work culture. Germans strive for streamlined processes, optimized workflows, and achieving results in a timely manner. They value individuals who can identify areas for improvement and implement innovative solutions to enhance productivity. Continuous improvement and maximizing output within given resources are highly regarded. Germans appreciate a goal-oriented approach and expect professionals to be proactive in managing their tasks efficiently.

German Work Ethic and Values

“arbeitsmoral” (work ethic) in germany.

The German work ethic, known as “Arbeitsmoral,” reflects a strong sense of dedication, discipline, and diligence towards work. Professionals in Germany take pride in their work and strive for excellence, contributing to the nation’s reputation for high-quality products and services.

Core values that drive the German work culture

Precision and attention to detail.

Germans take great pride in their meticulousness and attention to detail. They strive for perfection in their work and pay close attention to even the smallest aspects of a task or project. Precision is valued because it ensures that work is executed accurately and to the highest standards. Germans believe that attention to detail leads to quality outcomes and reflects a commitment to excellence.

Reliability and Trustworthiness

Reliability and trustworthiness are fundamental values in German work culture. Professionals are expected to fulfill their commitments and deliver on their promises. Meeting deadlines and honoring agreements are essential for building trust in professional relationships. Germans value reliability because it ensures that colleagues and business partners can depend on one another. Trust is a vital component of successful collaborations and long-term partnerships.

Long-Term Planning and Stability

German work culture places a strong emphasis on long-term planning and stability. Professionals prioritize sustainable growth and aim for stability in business operations. They value consistency and prefer to avoid unnecessary risks. Germans believe that long-term planning allows for better decision-making and helps organizations withstand economic fluctuations. Stability provides a solid foundation for businesses to thrive and succeed in the long run.

Professional Qualifications and Expertise

German professionals highly value educational qualifications and professional expertise. Continuous learning and skill development are regarded as essential for career advancement and success. Professionals are encouraged to pursue higher education, attend industry-specific training programs, and stay updated with the latest trends and developments in their fields. Germans recognize that professional qualifications and expertise contribute to the overall quality and competitiveness of the workforce.

Dedication to Work and Willingness to Go the Extra Mile

Germans exhibit a strong work ethic and a dedication to their work. They are known for their willingness to put in the effort required to excel in their roles. Going the extra mile is seen as a virtue and is appreciated in the workplace. German professionals take pride in their work and often go above and beyond to achieve exceptional results. This commitment to excellence not only benefits individuals but also contributes to the overall success of organizations.

Shaking Hands in German Work Culture

Significance of handshakes as a common form of greeting in professional settings.

Handshakes play a significant role in German work culture as a standard form of greeting in professional settings. It serves as an initial gesture of respect and trust-building.

Proper etiquette for handshakes in Germany

Firm handshake with direct eye contact.

When shaking hands in Germany, it is important to offer a firm handshake with direct eye contact. This demonstrates confidence, respect, and professionalism.

The role of handshakes in establishing trust and respect

Handshakes are considered a crucial aspect of establishing trust and respect in German work culture. It sets the tone for the beginning of a professional relationship and conveys sincerity and goodwill.

Importance of shaking hands with everyone present when entering or leaving a meeting

When entering or leaving a meeting in Germany, it is customary to shake hands with everyone present individually. This practice ensures that each person feels acknowledged and respected.

Overtime in the German Work Culture

Overview of the attitude towards overtime in german workplaces.

German work culture places importance on maintaining a healthy work-life balance, which limits the reliance on overtime. While there are exceptions, the overall approach to overtime differs from cultures that prioritize long working hours.

The approach to overtime

Respect for work-life balance and limited reliance on overtime.

German workplaces prioritize the well-being and work-life balance of employees. Overtime is not seen as the norm but rather reserved for urgent or critical situations.

Overtime as an exception for urgent or critical situations

In Germany, overtime is typically seen as an exception and is used sparingly. It is reserved for situations that require immediate attention, such as project deadlines or unforeseen circumstances.

Efficient time management and productivity during regular working hours

Efficiency and productivity during regular working hours are highly valued in German work culture. Professionals are encouraged to manage their time effectively, prioritize tasks, and optimize workflows to accomplish their responsibilities within standard working hours.

Legal regulations regarding maximum working hours and overtime compensation

German labor laws prescribe maximum working hours and overtime compensation to protect employees’ rights. These regulations ensure that overtime is adequately compensated and helps maintain a healthy work-life balance.

Impact of Work Culture on Business Practices

How the german work culture influences business practices and strategies.

The German work culture significantly shapes business practices and strategies in the country. Understanding these influences can help individuals and businesses navigate the German market effectively.

The benefits and challenges associated with German work culture

High-quality standards and meticulousness.

German work culture’s focus on high-quality standards and attention to detail contributes to the country’s reputation for precision and reliability. This emphasis benefits businesses by ensuring the delivery of exceptional products and services.

Lengthy decision-making processes and bureaucracy

German work culture can be characterized by lengthy decision-making processes and bureaucratic structures. While this can sometimes slow down decision-making, it also ensures thorough evaluation and consideration of options, leading to well-informed choices.

Striking a balance between work and personal life

The emphasis on work-life balance in German work culture can benefit both individuals and businesses. It helps maintain employee well-being, reduces burnout, and fosters a motivated and engaged workforce. However, it may require businesses to adopt flexible working arrangements and policies that support work-life balance.

Work Culture Diversity in Germany

Recognition of the diverse work cultures within germany, regional variations.

Germany is a country with diverse regional cultures, and this diversity extends to work culture as well. Different regions may have unique work practices, communication styles, and business customs that professionals should be aware of when operating in specific areas.

Impact of globalization and multiculturalism on work culture

Globalization and multiculturalism have influenced work culture in Germany. With an increasingly diverse workforce and global connections, German businesses have embraced cultural diversity and fostered inclusive work environments.

Strategies for Thriving in the German Work Culture

Practical tips for individuals or businesses operating within the german work culture, embracing punctuality and respecting deadlines.

Adhering to schedules, being punctual for meetings, and respecting deadlines demonstrate professionalism and respect for others’ time.

Adapting to hierarchical structures and understanding authority

Understanding the hierarchical structure of organizations and respecting authority are crucial for effective communication and decision-making in German work culture.

Promoting work-life balance and employee well-being

Prioritizing work-life balance, implementing flexible working arrangements, and supporting employee well-being contribute to a positive work culture and enhance productivity.

Observing proper handshake etiquette

Understanding and practicing proper handshake etiquette, such as offering a firm handshake and maintaining eye contact, helps establish rapport and trust in professional interactions.

Recognizing the approach to overtime and adjusting workload management accordingly

Recognizing that overtime is the exception rather than the norm and effectively managing workloads within regular working hours promotes a healthy work-life balance and efficient productivity.

Future Trends and Evolution of German Work Culture

Potential changes in the german work culture influenced by societal shifts and technological advancements, societal shifts.

German society is experiencing various shifts that can influence work culture. For example, there is a growing emphasis on work-life balance and employee well-being. Professionals are seeking more flexibility and autonomy in their work arrangements, as well as a greater sense of purpose and meaning in their careers. These societal shifts can lead to changes in work culture, such as the adoption of flexible working hours, remote work options, and a focus on employee engagement and satisfaction.

Technological advancements

The rapid advancement of technology has a profound impact on work culture in Germany. Automation, artificial intelligence, and digital tools are reshaping workflows and processes, streamlining operations, and increasing efficiency. As technology continues to evolve, there may be a greater integration of digital platforms and tools into daily work practices, leading to new ways of collaboration, communication, and task management. This can result in a more digitized work culture, where employees are adept at using technology to perform their roles effectively.

The impact of remote work and digitalization on work culture in Germany

Remote work.

The increased adoption of remote work, especially accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has reshaped work culture in Germany. Remote work allows professionals to work from anywhere, providing flexibility and reducing the reliance on physical office spaces. This shift can lead to changes in work culture, such as a greater emphasis on trust and accountability, as well as the need for effective virtual communication and collaboration. Remote work also necessitates the development of digital skills and the adoption of remote-friendly tools and technologies.

Digitalization

Digitalization refers to the integration of digital technologies and processes into various aspects of work. It has transformed how work is conducted in Germany, making tasks more efficient, scalable, and accessible. The impact of digitalization on work culture includes the need for digital literacy and upskilling, as well as a shift in work practices to leverage digital tools and platforms. This can lead to increased collaboration through virtual meetings, document sharing, and project management tools. It also promotes a more data-driven approach to decision-making and performance evaluation.

Understanding the work culture in Germany is essential for professionals and businesses to succeed in the country’s competitive landscape. Key elements such as punctuality, respect for authority, work-life balance, teamwork, and a focus on efficiency shape the German work culture.

By understanding and adapting to the German work culture, individuals and businesses can navigate professional environments effectively, build strong relationships, and achieve success in Germany’s thriving economy.

Talk to our experts & get a free quote!

[email protected]

China: +86 215 211 0025, 75 e. santa clara st. floor 9, san jose, ca 95113, usa.

Please leave this field empty.

Select Service Employer of Record Payroll & Benefits

Select Location United States China Mexico United Kingdom ----- Argentina Australia Bangladesh Bulgaria Cambodia Canada Croatia Denmark Egypt Finland France Germany Greece Hong Kong Hungary India Indonesia Israel Italy Japan Luxembourg Malaysia Myanmar Netherlands Nigeria Norway Pakistan Panama Philippines Poland Romania Serbia Singapore South Africa South Korea Sri Lanka Sweden Switzerland Taiwan Thailand Tunisia Turkey United Arab Emirates Vietnam

By sending your inquiry, you consent to receiving marketing information from NNRoad, in accordance with the Privacy Policy .

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

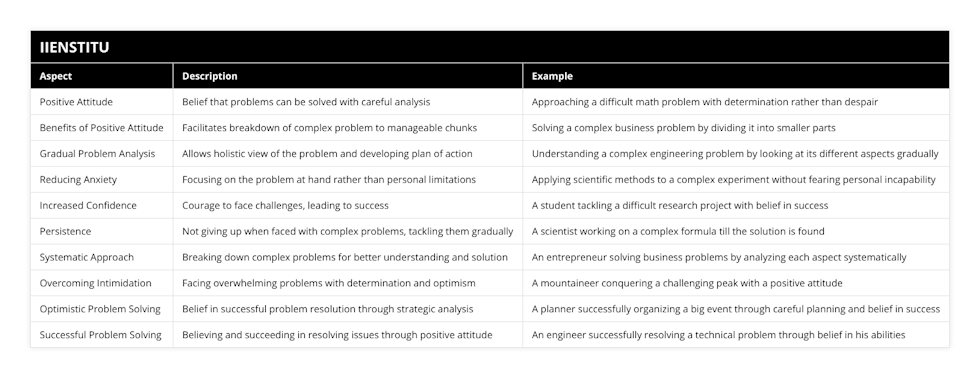

Brief research report article, the influence of attitudes and beliefs on the problem-solving performance.

- 1 Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Education of Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg, Germany

- 2 Hamburg Center for University Teaching and Learning, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

The problem-solving performance of primary school students depend on their attitudes and beliefs. As it is not easy to change attitudes, we aimed to change the relationship between problem-solving performance and attitudes with a training program. The training was based on the assumption that self-generated external representations support the problem-solving process. Furthermore, we assumed that students who are encouraged to generate representations will be successful, especially when they analyze and reflect on their products. A paper-pencil test of attitudes and beliefs was used to measure the constructs of willingness, perseverance, and self-confidence. We predicted that participation in the training program would attenuate the relationship between attitudes and problem-solving performance and that non-participation would not affect the relationship. The results indicate that students’ attitudes had a positive effect on their problem-solving performance only for students who did not participate in the training.

Introduction

Mathematical problem solving is considered to be one of the most difficult tasks primary students have to deal with ( Verschaffel et al., 1999 ) since it requires them to apply multiple skills ( De Corte et al., 2000 ). It is decisive in this respect that “difficulty should be an intellectual impasse rather than a computational one” ( Schoenfeld, 1985 , p. 74). When solving problems, it is not enough to retrieve procedural knowledge and reproduce a known solution approach. Rather, problem-solving tasks require students to come up with new ways of thinking ( Bransford and Stein, 1993 ). Problem-solvers must activate their existing knowledge network and adapt it to the respective problem situation ( van Dijk and Kintsch, 1983 ). They have to succeed in generating an adequate representation of the problem situation (e.g., Mayer and Hegarty, 1996 ). This requires conceptual knowledge, which novice problem-solvers have to acquire ( Bransford et al., 2000 ). As problem solving is the foundation for learning mathematics, an important goal of primary school mathematics teaching is to strengthen students’ problem-solving performance. One central problem is that problem-solving performance is highly influenced by students’ attitudes towards problem solving ( Reiss et al., 2002 ; Schoenfeld, 1985 ; Verschaffel et al., 2000 ).

Attitudes and beliefs are considered quite stable once they are developed ( Hannula, 2002 ; Goldin, 2003 ). However, students who are novices in a particular content area are still in the process of development, as are their attitudes and beliefs. It can therefore be assumed that their attitudes change over time ( Hannula, 2002 ). However, such a change does not take place quickly ( Higgins, 1997 ; Mason and Scrivani, 2004 ). Nevertheless, in a shorter period of time, it might be possible to reduce the influence of attitudes on problem-solving performance ( Hannula et al., 2019 ). In this paper, we present a training program for primary school students, which aims to do exactly that.

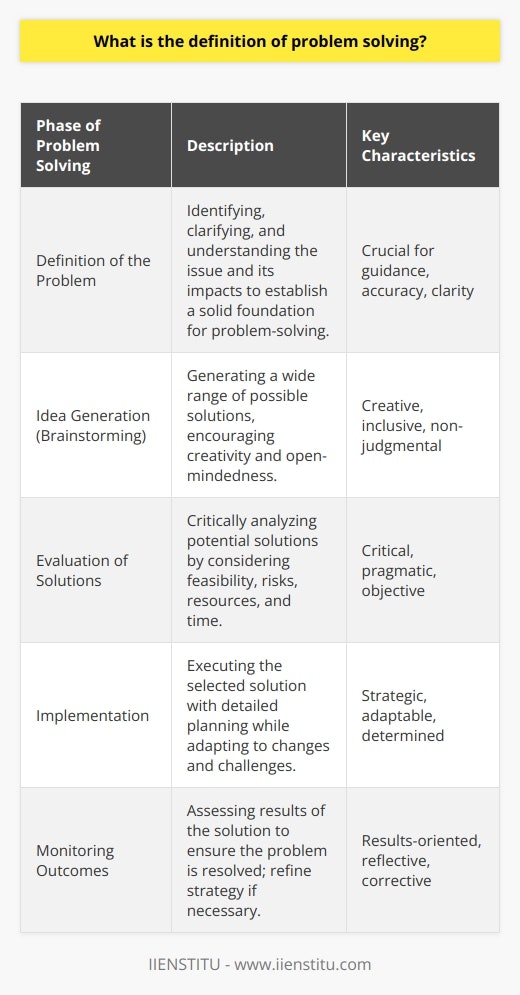

Problem-Solving Performance

Successful problem solving can be observed on two levels: problem-solving success and problem-solving skills. Many studies measure the problem-solving performance of students on the basis of correctly or incorrectly solved problem-solving tasks, that is, the product (e.g., Boonen et al., 2013 ; de Corte et al., 1992 ; Hegarty et al., 1992 ; Verschaffel et al., 1999 ). In this case, only problem-solving success, that is, specifically whether the numerically obtained result is correct or incorrect, is evaluated. This is a strict assessment measure, since the problem-solving process is not taken into account. As a result, the problem-solving performance is only considered from a single, product-oriented perspective. For instance students’ performance is assessed as unsuccessful when they apply an essentially correct procedure or strategy but achieve the wrong result, or it is considered successful when students achieve the right result even though they have misunderstood the problem ( Lester and Kroll, 1990 ). An advantage of this operationalization, however, is that student performance tends to be underestimated rather than overestimated.

A more differentiated view of successful problem solving includes the solver’s problem-solving process ( Lester and Kroll, 1990 ; cf. Adibnia and Putt, 1998 ). In this way, sub-skills such as understanding the problem, adequately representing the situation, applying strategies, or achieving partial solutions are taken into account. These are then incorporated into the evaluation of performance and, thus, of problem-solving skills ( Charles et al., 1987 ; cf. Sturm, 2019 ). The advantage of this operationalization option is that it also takes into account smaller advances by the solver, although they may not yet lead to the correct result. It is therefore less likely to underestimate students’ performance. In order to assess and evaluate the problem-solving skills of students in the best way and, thus, avoid over- and under-estimating their skills, direct observation and questioning should be implemented (e.g., Lester and Kroll, 1990 ). An analysis of written work should not be the only means of assessment ( Lester and Kroll, 1990 ).

Attitudes and Beliefs

Attitudes are dispositions to like or dislike objects, persons, institutions, or events ( Ajzen, 2005 ). They influence behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Therefore, it is not surprising that attitudes–which are sometimes also synonymously referred to as beliefs–are a central construct in psychology ( Ajzen, 2005 ).

Individual attitudes to word problems influence, albeit rather unconsciously, approaches to such problems and willingness to learn mathematics and solve problems ( Grigutsch et al., 1998 ; Awofala, 2014 ). Research on attitudes of primary students to word problems is scarce. Most research focuses on students with well-established attitudes. However, the importance of the attitudes of younger children is undisputed ( Di Martino, 2019 ). Di Martino (2019) conducted a study on kindergarten children as well as on first-, third-, and fifth-graders and found that, with increasing age, students’ perceived competence in problem solving decreases, and negative emotions towards mathematical problems increase. Whether a solver can overcome problem barriers when dealing with word problems depends not only on his or her previous knowledge, abilities, and skills, but also on his or her attitudes and beliefs ( Schoenfeld, 1985 ; Verschaffel et al., 2000 ; Reiss et al., 2002 ). It has been shown many times that attitudes towards problem solving are influencing factors on performance and learning success which should not be underestimated ( Charles et al., 1987 ; Lester et al., 1989 ; Lester & Kroll, 1990 ; De Corte et al., 2002 ; Goldin et al., 2009 ; Awofala, 2014 ). Learners associate a specific feeling with an object, in this case with a word problem, triggering a specific emotional state ( Grigutsch et al., 1998 ). The feelings and states generated are subjective and can therefore vary between individuals ( Goldin et al., 2009 ).

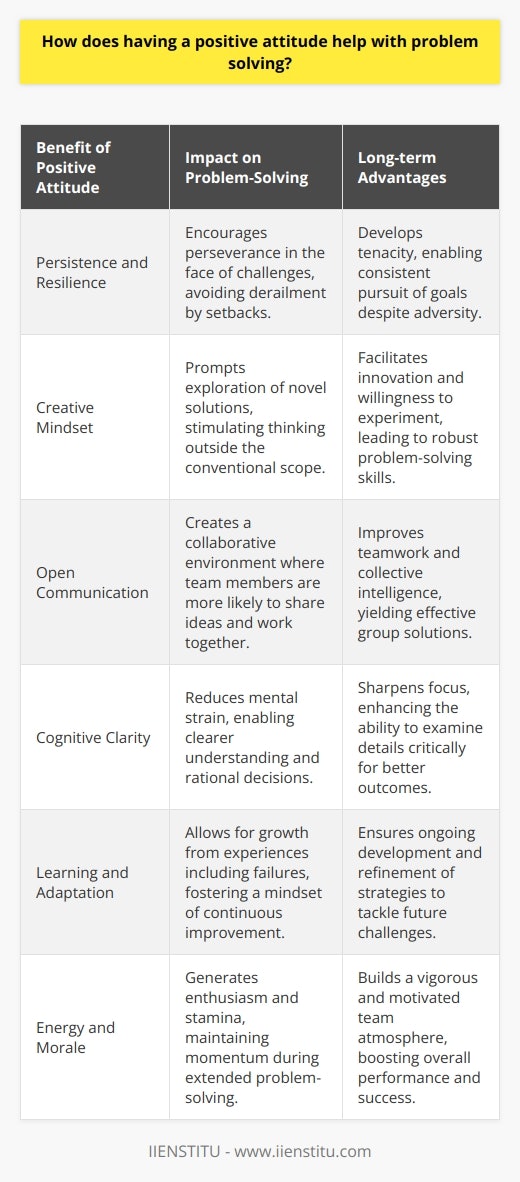

Attitudes towards problem solving can be divided into willingness, perseverance, and self-confidence ( Charles et al., 1987 ; Lester et al., 1989 ). This distinction comes from the Mathematical Problem-Solving Project, in which Webb, Moses, and Kerr (1977) found that willingness to solve problems, perseverance in attempting to find a solution, and self-confidence in the ability to solve problems are the most important influences on problem-solving performance. When students are willing to work on a variety of mathematics tasks and persevere with tasks until they find a solution, they are more task oriented and easier to motivate ( Reyes, 1984 ). Perseverance is defined as the willing pursuit of a goal-oriented behavior even if this involves overcoming obstacles, difficulties, and disappointments ( Peterson and Seligman, 2004 ). Confidence is an individual’s belief in his or her ability to succeed in solving even challenging problems as well as an individual’s belief in his or her own competence with respect to his or her peers ( Lester et al., 1989 ). Students’ lack of confidence in themselves as problem-solvers or their beliefs about mathematics can considerably undermine their ability to solve or even approach problems in a productive way ( Shaughnessy, 1985 ). The division of attitudes into these three sub-categories can also be found in current studies ( Zakaria and Yusoff, 2009 ; Zakaria and Ngah, 2011 ).

Reducing the Influence of Attitudes and Beliefs

As it seems impossible to change attitudes within a short time frame, we developed a training program to reduce the influence of attitudes on problem solving, on the one hand, and to foster the problem-solving performance of primary-school students, on the other hand.

The training program was an integral part of regular math classes and focused on teaching students to generate and use external representations ( Sturm, 2019 ; Sturm et al., 2016 ; Sturm and Rasch, 2015 ; see also Supplementary Appendix A ). Such a program that concentrates on the strengths and weaknesses of novices and on their individually generated external representations can be a benefit for primary-school students in two ways. The class discusses how the structure described in the problem can be adequately represented so that the solution can be found, working out multiple approaches based on different student representations. The students are thus exposed to ideas about how a problem can be solved in different ways. Such a training program fulfils, albeit rather implicitly, another essential component. By respectfully considering their individual thoughts and difficulties, the students are made aware of their strengths and their creativity and of the fact that there is not a single correct approach or solution that everyone has to find ( Lester and Cai, 2016 ; Di Martino, 2019 ). This can counteract fears of failure and lack of self-confidence, and generate positive attitudes ( Lester and Cai, 2016 ; Di Martino, 2019 ). The teacher pays attention to the solution process rather than to the numerical result in order to reduce the influence of attitudes on performance ( Di Martino, 2019 ). In the same way, experiencing success and perceiving increasing flexibility and agility can reduce the influence of attitudes. As a result, we expected attitudes and beliefs to have a smaller effect on problem-solving performance.

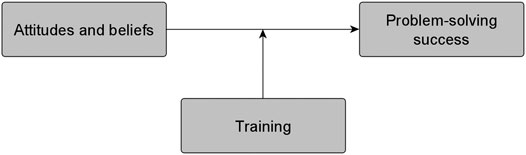

Based on previous research, our goal was to reduce the influence of attitudes on the problem-solving performance of students (see Figure 1 ). To this end, the hypothesis was derived that participation in the training program would minimize the effect of attitudes and beliefs on problem-solving success, so that students would succeed at the end of the training despite initial negative attitudes and beliefs.

FIGURE 1 . The moderation model with the single moderator variable training influencing the effect of attitudes and beliefs on problem-solving success.

Participants

In total 335 students from 20 Grade 3 classes from eight different primary schools in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate took part in the intervention study (172 boys and 163 girls). Nineteen students dropped out because of illness during the intervention. The age of the participants ranged between seven and ten years ( M = 8.10, SD = 0.47).

This investigation was part of a large interdisciplinary project 1 . A central focus of the project was to investigate whether representation training has a demonstrable effect on the performance of third-graders (cf. Sturm, 2019 ). For this reason, we implemented a pretest-posttest control group design. The intervention took place between Measurement Points 1 and 2. We measured the problem-solving performance of the students with a word-problem-solving test (WPST) at Measurement Points 1 and 2. All other variables were measured at Measurement Point 1 only (factors to establish comparable experimental conditions: intelligence, text comprehension, and mathematical abilities; co-variates for the mediation model: metacognitive skills, mathematical abilities).

In the intervention, third-grade students worked on challenging word problems for one regular mathematics lesson a week. The intervention was based on six task types with different structures ( Sturm and Rasch, 2015 ): 1) comparison tasks, 2) motion tasks, 3) tasks involving comparisons and balancing items or money, 4) tasks involving combinatorics, 5) tasks in which structure reflects the proportion of spaces and limitations, and 6) tasks with complex information. Two word problems were included for each task type and were presented to all classes in the same random sequence. Each task had to be completed in a maximum of one lesson.

The training was implemented for half of the classes and was conducted by the first author; the other half worked on the tasks with their regular mathematics teacher. They were not informed on the purpose of the intervention and not given any instructions on how to process the tasks. In the lessons for students doing the training, the students were explicitly cognitively stimulated to generate external representations and to use them to develop solutions. They were repeatedly encouraged to persevere and not to give up. The diverse external representations generated by the students were analyzed, discussed, and compared by the class during the training. They jointly identified the characteristics of representations that enabled them to specifically solve the tasks and identified different approaches (for more details about the study, see Sturm and Rasch, 2015 ). With the goal of reducing the influence of attitudes on performance, the class worked directly on the students’ own representations instead of on prefabricated representations. The aim was that students realized that it was worthwhile investing effort into creating representations and that they were able to solve problem tasks independently.

Thus, the study was composed of two experimental conditions: training program ( n = 176; 47% boys) (hereinafter abbreviated to T+) and no training program ( n = 159; 58% boys) (hereinafter abbreviated to T-). In order to control potential interindividual differences, the 20 classes were assigned to the experimental conditions by applying parallelization at class level ( Breaugh and Arnold, 2007 ; Myers and Hansen, 2012 ). The classes were grouped into homogeneous blocks using the R package blockTools Version 0.6-3 and then randomly assigned to the experimental conditions ( Greevy et al., 2004 ; Moore, 2012 ; see also Supplementary Appendix B for more information).

Word-Problem-Solving Test

Before the intervention and immediately after it, the students worked on a WPST, which we created. It consisted in each case of three challenging word problems with an open answer format. Each of the three tasks represented a different type of problem. The word problems from the WPST at Measurement Point 1 and the word problems from the WPST at Measurement Point 2 had the same structure. We implemented two parallel versions; only the context was changed by exchanging single words (see Supplementary Appendix C ). An example of an item from the test is a task with complex information ( Sturm, 2018 ): Classes 3a and 3b go to the computer room. Some students have to work at a computer in pairs. In total there are 25 computers, but 40 students. How many students work alone at a computer? How many students work at a computer in pairs? Direct observation and questioning could not be conducted due to the large number of participants in the project; only the students’ written work was available for analysis. The problem-solving process of the students could therefore only be assessed indirectly. For this reason, the performance of students in the two tests was evaluated based on problem-solving success, ruling out overestimation of performance.

Problem-Solving Success

The success of the solution was measured dichotomously in two forms: 1) correct solution and (0) incorrect solution. Only the correctness of the result achieved was evaluated. This dependent variable acted as a strict criterion that could be quantified with high observer agreement (κ = 0.97; κ min = 0.93, κ max = 1.00). A confirmatory factor analysis using the R package lavaan version 0.6-7 confirmed that the WPST measured the one-dimensional construct problem-solving success. The one-dimensional model exhibited a good model fit ( Nussbeck et al., 2006 ; Hair et al., 2009 ): χ 2 (27) = 36.613, p = 0.103; χ 2 /df = 1.356, CFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.981, SRMR = 0.032, RMSEA = 0.033 ( p = 0.854). The reliability coefficients at Measurement Point 1 were classified as low (Cronbach’s α = 0.39) because the test consisted of only three items ( Eid et al., 2011 ) and a homogeneous sample was required at this measurement point ( Lienert and Raatz, 1998 ). The Cronbach’s alpha for the second measurement point (α = 0.60) was considered to be sufficient ( Hair et al., 2009 ). The test score represented the mean value of all three task scores.

Attitudes and Beliefs About Problem Solving

The attitudes and beliefs of the learners were recorded with the Attitudes Inventory Items ( Webb et al., 1977 ; Charles et al., 1987 ). The original questionnaire comprises 20 items, which are measured dichotomously (“I agree” and “I disagree”). The Attitudes Inventory measures the three categories of attitudes and beliefs related to problem solving: a) willingness (six items), b) perseverance (six items), and c) self-confidence (eight items). An example of an item for willingness is: “I will try to solve almost any problem.” An example of an item for perseverance is: “When I do not get the right answer right away, I give up.” An example of an item for self-confidence is: “I am sure I can solve most problems.”

Because the reported reliabilities were only satisfactory to some extent (α = 0.79, mean = 0.64) ( Webb et al., 1977 ), the Attitudes Inventory was initially tested on a smaller sample ( n = 74; M = 8.6 years old; 59% girls). A satisfactory Cronbach’s α = 0.86 was achieved (mean α = 0.73). The number of items was reduced to 13 (four items for willingness, four items for perseverance, five items for self-confidence), which had only a minor influence on reliability (α = 0.83). For economic reasons, the shortened questionnaire was used in the study. The three-factor structure of the questionnaire was confirmed with a confirmatory factor analysis using the R package lavaan version 0.6–7. As the fit indices show, the three-factor model had a good model fit: χ 2 (62) = 134.856, p < 0.001; χ 2 / df = 2.175, CFI = 0.948, TLI = 0.935, RMSEA = 0.062 ( p = 0.086) ( Hair et al., 2009 ; Brown, 2015 ). The three-factor model had a better fit than the single-factor model ( p = 0.0014): χ 2 (65) = 152.121, p < 0.001; χ 2 / df = 2.340, CFI = 0.938, TLI = 0.926, SRMR = 0.061, RMSEA = 0.066 ( p = 0.028). The students were grouped into three groups ( M –1 SD ; M ; M +1 SD ). The responses were coded in such a way that high scores ( M +1 SD ) indicated positive attitudes and beliefs, and low scores ( M –1 SD ) indicated negative attitudes and beliefs.

Additional Influencing Factors

In order to ensure the internal validity of the investigation, we collected student-related factors that influence the solution of word problems from a theoretical and empirical point of view. It has been shown that the mathematical abilities and metacognitive skills of students significantly influence their performance ( Sturm et al., 2015 ).

Mathematical Abilities

The basic mathematical abilities were determined using a standardized German-language test as a group test (Heidelberger Rechentest HRT 1–4, Haffner et al., 2005 ). The test consists of eleven subtests, from which three scale values were determined: calculation operations, numerical-logical and spatial-visual skills as well as the overall performance for all eleven subtests. The reliability was only satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 0.74). Total performance was included in the study.

Metacognitive Skills

The metacognitive skills of the students were measured using a paper-pencil version of EPA2000, a test to measure metacognitive skills before and/or after the solving of tasks ( Clercq et al., 2000 ). The prediction skills and evaluation skills of the students were collected for all three word problems of the WPST using a 4-point rating scale: 1) “absolutely sure, it’s wrong,” 2) “sure, it’s wrong,” 3) “sure, it’s right,” and 4) “absolutely sure, it’s right” ( Clercq et al., 2000 ). If the students’ assessments of “absolutely sure” matched their solution, they were awarded 2 points. If they agreed with “sure,” they received 1 point. No match was scored with 0 points ( Desoete et al., 2003 ). The reliabilities were only satisfactory (Cronbach’s α total =0.74, α prediction =0.56, α evaluation = 0.73). A confirmatory factor analysis revealed that prediction skills and evaluation skills represent a single factor (χ 2 (9) = 16.652, p < 0.001; χ 2 / df = 1.850, CFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.919, RMSEA = 0.053 ( p = 0.396)). The aggregated factor was used as a control variable in the moderator analysis.

In addition to the variables considered in this paper, text comprehension and intelligence were also surveyed in the project. However, they are not the focus of this paper; additional information can be found in Sturm et al. (2015) .

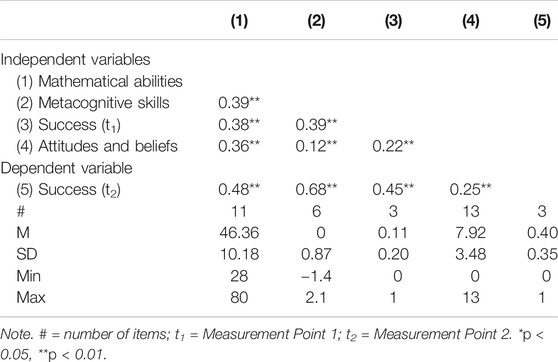

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Between the Measures

The descriptive statistics and correlations of all scales are presented in Table 1 (see Supplementary Appendix D for a separate overview for each of the experimental conditions). The signs for all correlations were as expected. The variable training program is not listed because it is the dichotomous moderator variable (T+ and T−).

TABLE 1 . Descriptive statistics and correlations of all variables for both experimental conditions.

Moderated Regression Analyses

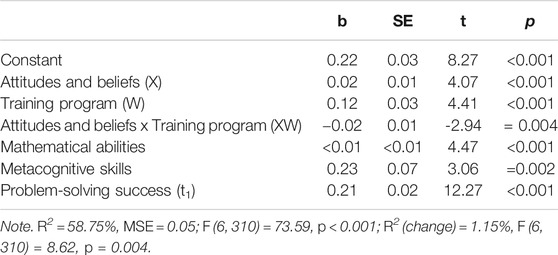

The hypothesis was tested with a moderated regression analysis using product terms from mean-centered predictor variables ( Hayes, 2018 ). This model imposed the constraint that any effect of attitudes and beliefs was independent of all other variables in the model. This was achieved by controlling for mathematical abilities, metacognitive skills, and problem-solving performance at Measurement Point 1. The estimated main effects and interaction terms are presented in Table 2 .

TABLE 2 . Results from the regression analysis examining the moderation of the effect of attitudes and beliefs on problem-solving success (t 2 ) by participation in the training program, controlling for mathematical abilities, metacognitive skills, and problem-solving success from the pretest.

When testing the hypothesis, we found a significant main effect of attitudes and beliefs, a significant main effect of the training program, and a significant moderator effect of the training on attitudes and beliefs as a predictor of problem-solving success. The main effect of the training program indicated that students who participated in the training performed better in the second WPST. The main effect of attitudes and beliefs showed that students with more positive attitudes and beliefs were more successful than students with negative attitudes and beliefs.

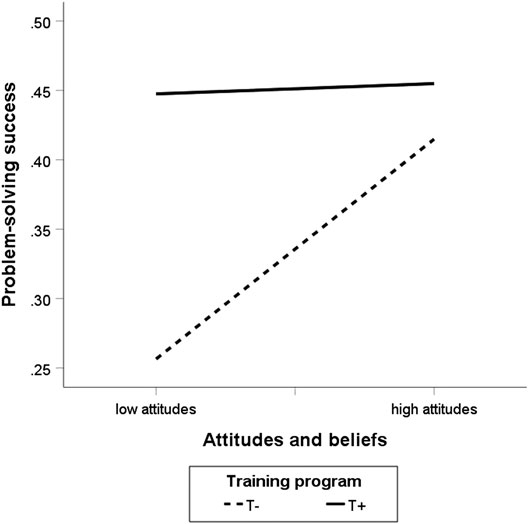

To further explore the interaction between attitudes and beliefs and the training program, we analyzed simple slopes at values of 1 SD above and 1SD below the means of attitudes and beliefs ( Hayes, 2018 ). As can be seen from the conditional expectations in Figure 2 , attitudes and beliefs did not affect the problem-solving success of students who participated in the training program. Attitudes and beliefs only had a positive effect on the problem-solving success of students who did not participate in the training.

FIGURE 2 . Moderator effect of the training program on problem-solving success at Measurement Point 2.

Our results confirm previous findings that the attitudes and beliefs of students correlate with their problem-solving performance. They indicate that this correlation can be moderated by student participation in a training program. Negative attitudes and beliefs did not affect the performance of students who participated in a problem-solving training program over several weeks. Whether the training program also causes a change in the attitudes and beliefs of the students over time has to be investigated in a follow-up study, which is planned with a longer intervention period with at least two measurements of attitudes and beliefs. A longer intervention period would have the advantage that attitudes develop depending on the individual experiences of a person ( Hannula, 2002 ; Lim and Chapman, 2015 ), for instance, when new experience is gathered or new knowledge is acquired (e.g., Ajzen, 2005 ).

Some limitations need to be considered when interpreting the results of the study. For example, the mitigating processes need to be investigated further. It is also unclear as to which components of the training are ultimately responsible for counteracting the effect of attitudes and beliefs. Although the study did not provide results in this regard, we assume that the following factors might have an effect: generating external representations, reflecting on the representations together as a group, and fostering an appreciative and constructive approach to mistakes. Further studies are needed to show whether and to what extent these factors actually attenuate the effect of attitudes and beliefs.

Furthermore, the measurement instruments for the control variables mathematical abilities and metacognitive skills were rather limited. If researchers are interested in understanding further effects of metacognitive skills, more aspects should be included. Furthermore, according to Lester et al. (1987), investigating attitudes and beliefs using a questionnaire is associated with disadvantages. How accurately students answer the questions depends on how objectively and accurately they can reflect on and assess their own attitudes. Misinterpretations and errors cannot be ruled out. The most serious disadvantage, however, is that data collection using an inventory can easily be assumed to have unjustified validity and reliability. For a deeper insight into the attitudes and beliefs of primary school students, qualitative interviews have to be implemented.

However, for the purpose of this study, it seems sufficient to consider the two control variables mathematical abilities and metacognitive abilities. We were able to ensure that the correlation between attitudes and beliefs and the mathematical performance of students was not influenced by these factors.

Regardless of the limitations, our study has some practical implications. Participation in the training program, independently of the mathematical abilities and text comprehension of students, reduced the influence of attitudes and beliefs on their performance. Thus, for teaching practice, it can be concluded that it is important not only to implement regular problem-solving activities in mathematics lessons, but also to encourage students to externalize and find their own solutions. The aim is to establish a teaching culture that promotes a variety of approaches and procedures, allows mistakes to be made, and makes mistakes a subject for learning. Reflecting on different possible solutions and also on mistakes helps students to progress. Thus, students develop a repertoire of external representations from which they can profit in the long term when solving problems.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology, University of Koblenz and Landau, Germany. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian. This study was also carried out in accordance with the guidelines for scientific studies in schools in the German state Rhineland-Palatinate (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen an Schulen in Rheinland-Pfalz), Aufsichts- und Dienstleistungsdirektion Trier. The protocol was approved by the Aufsichts- und Dienstleistungsdirektion Trier.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

The project was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, grant number GK1561/1).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.525923/full#supplementary-material

1 This project was part of the first author’s PhD thesis

Adibnia, A., and Putt, I. J. (1998). Teaching problem solving to year 6 students: A new approach. Math. Educ. Res. J. 10 (3), 42–58. doi:10.1007/BF03217057

Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, personality and behavior . Maidenhead, United Kingdom: Open University Press .

Google Scholar

Ajzen, I. (1998). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Proc. 50 (2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Amarel, S. (1966). On the mechanization of creative processes. IEEE Spectr. 3 (4), 112–114. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.1966.5216589

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Awofala, A. O. A. (2014). Examining personalisation of instruction, attitudes toward and achievement in mathematics word problems among nigerian senior secondary school students. Ijemst 2 (4), 273–288. doi:10.18404/ijemst.91464

Boonen, A. J. H., van der Schoot, M., van Wesel, F., de Vries, M. H., and Jolles, J. (2013). What underlies successful word problem solving? A path analysis in sixth grade students. Contemporary Educ. psychol. 38 (3), 271–279. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.05.001

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., and Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn: brain, mind, experience, and school . Washington, DC: National Academy Press .

Bransford, J. D., and Stein, B. S. (1993). The ideal problem solver: a guide for improving thinking, learning, and creativity . 2nd Edn. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman .

Breaugh, J. A., and Arnold, J. (2007). Controlling nuisance variables by using a matched-groups design. Organ. Res. Methods 10 (3), 523–541. doi:10.1177/1094428106292895

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research . 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press .

Charles, R. I., Lester, F. K., and O’Daffer, P. G. (1987). How to evaluate progress in problem solving . Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics .

Clercq, A. D., Desoete, A., and Roeyers, H. (2000). Epa2000: a multilingual, programmable computer assessment of off-line metacognition in children with mathematical-learning disabilities. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 32 (2), 304–311. doi:10.3758/BF03207799

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cox, R., and Brna, P. (1995). Supporting the use of external representation in problem solving: the need for flexible learning environments. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 6 (2–3), 239–302. .