- Privacy Policy

Home » Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Significance of the Study

Definition:

Significance of the study in research refers to the potential importance, relevance, or impact of the research findings. It outlines how the research contributes to the existing body of knowledge, what gaps it fills, or what new understanding it brings to a particular field of study.

In general, the significance of a study can be assessed based on several factors, including:

- Originality : The extent to which the study advances existing knowledge or introduces new ideas and perspectives.

- Practical relevance: The potential implications of the study for real-world situations, such as improving policy or practice.

- Theoretical contribution: The extent to which the study provides new insights or perspectives on theoretical concepts or frameworks.

- Methodological rigor : The extent to which the study employs appropriate and robust methods and techniques to generate reliable and valid data.

- Social or cultural impact : The potential impact of the study on society, culture, or public perception of a particular issue.

Types of Significance of the Study

The significance of the Study can be divided into the following types:

Theoretical Significance

Theoretical significance refers to the contribution that a study makes to the existing body of theories in a specific field. This could be by confirming, refuting, or adding nuance to a currently accepted theory, or by proposing an entirely new theory.

Practical Significance

Practical significance refers to the direct applicability and usefulness of the research findings in real-world contexts. Studies with practical significance often address real-life problems and offer potential solutions or strategies. For example, a study in the field of public health might identify a new intervention that significantly reduces the spread of a certain disease.

Significance for Future Research

This pertains to the potential of a study to inspire further research. A study might open up new areas of investigation, provide new research methodologies, or propose new hypotheses that need to be tested.

How to Write Significance of the Study

Here’s a guide to writing an effective “Significance of the Study” section in research paper, thesis, or dissertation:

- Background : Begin by giving some context about your study. This could include a brief introduction to your subject area, the current state of research in the field, and the specific problem or question your study addresses.

- Identify the Gap : Demonstrate that there’s a gap in the existing literature or knowledge that needs to be filled, which is where your study comes in. The gap could be a lack of research on a particular topic, differing results in existing studies, or a new problem that has arisen and hasn’t yet been studied.

- State the Purpose of Your Study : Clearly state the main objective of your research. You may want to state the purpose as a solution to the problem or gap you’ve previously identified.

- Contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

- Addresses a significant research gap.

- Offers a new or better solution to a problem.

- Impacts policy or practice.

- Leads to improvements in a particular field or sector.

- Identify Beneficiaries : Identify who will benefit from your study. This could include other researchers, practitioners in your field, policy-makers, communities, businesses, or others. Explain how your findings could be used and by whom.

- Future Implications : Discuss the implications of your study for future research. This could involve questions that are left open, new questions that have been raised, or potential future methodologies suggested by your study.

Significance of the Study in Research Paper

The Significance of the Study in a research paper refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic being investigated. It answers the question “Why is this research important?” and highlights the potential contributions and impacts of the study.

The significance of the study can be presented in the introduction or background section of a research paper. It typically includes the following components:

- Importance of the research problem: This describes why the research problem is worth investigating and how it relates to existing knowledge and theories.

- Potential benefits and implications: This explains the potential contributions and impacts of the research on theory, practice, policy, or society.

- Originality and novelty: This highlights how the research adds new insights, approaches, or methods to the existing body of knowledge.

- Scope and limitations: This outlines the boundaries and constraints of the research and clarifies what the study will and will not address.

Suppose a researcher is conducting a study on the “Effects of social media use on the mental health of adolescents”.

The significance of the study may be:

“The present study is significant because it addresses a pressing public health issue of the negative impact of social media use on adolescent mental health. Given the widespread use of social media among this age group, understanding the effects of social media on mental health is critical for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. This study will contribute to the existing literature by examining the moderating factors that may affect the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes. It will also shed light on the potential benefits and risks of social media use for adolescents and inform the development of evidence-based guidelines for promoting healthy social media use among this population. The limitations of this study include the use of self-reported measures and the cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference.”

Significance of the Study In Thesis

The significance of the study in a thesis refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic and the potential impact of the study on the field of study or society as a whole. It explains why the research is worth doing and what contribution it will make to existing knowledge.

For example, the significance of a thesis on “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare” could be:

- With the increasing availability of healthcare data and the development of advanced machine learning algorithms, AI has the potential to revolutionize the healthcare industry by improving diagnosis, treatment, and patient outcomes. Therefore, this thesis can contribute to the understanding of how AI can be applied in healthcare and how it can benefit patients and healthcare providers.

- AI in healthcare also raises ethical and social issues, such as privacy concerns, bias in algorithms, and the impact on healthcare jobs. By exploring these issues in the thesis, it can provide insights into the potential risks and benefits of AI in healthcare and inform policy decisions.

- Finally, the thesis can also advance the field of computer science by developing new AI algorithms or techniques that can be applied to healthcare data, which can have broader applications in other industries or fields of research.

Significance of the Study in Research Proposal

The significance of a study in a research proposal refers to the importance or relevance of the research question, problem, or objective that the study aims to address. It explains why the research is valuable, relevant, and important to the academic or scientific community, policymakers, or society at large. A strong statement of significance can help to persuade the reviewers or funders of the research proposal that the study is worth funding and conducting.

Here is an example of a significance statement in a research proposal:

Title : The Effects of Gamification on Learning Programming: A Comparative Study

Significance Statement:

This proposed study aims to investigate the effects of gamification on learning programming. With the increasing demand for computer science professionals, programming has become a fundamental skill in the computer field. However, learning programming can be challenging, and students may struggle with motivation and engagement. Gamification has emerged as a promising approach to improve students’ engagement and motivation in learning, but its effects on programming education are not yet fully understood. This study is significant because it can provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of gamification in programming education and inform the development of effective teaching strategies to enhance students’ learning outcomes and interest in programming.

Examples of Significance of the Study

Here are some examples of the significance of a study that indicates how you can write this into your research paper according to your research topic:

Research on an Improved Water Filtration System : This study has the potential to impact millions of people living in water-scarce regions or those with limited access to clean water. A more efficient and affordable water filtration system can reduce water-borne diseases and improve the overall health of communities, enabling them to lead healthier, more productive lives.

Study on the Impact of Remote Work on Employee Productivity : Given the shift towards remote work due to recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, this study is of considerable significance. Findings could help organizations better structure their remote work policies and offer insights on how to maximize employee productivity, wellbeing, and job satisfaction.

Investigation into the Use of Solar Power in Developing Countries : With the world increasingly moving towards renewable energy, this study could provide important data on the feasibility and benefits of implementing solar power solutions in developing countries. This could potentially stimulate economic growth, reduce reliance on non-renewable resources, and contribute to global efforts to combat climate change.

Research on New Learning Strategies in Special Education : This study has the potential to greatly impact the field of special education. By understanding the effectiveness of new learning strategies, educators can improve their curriculum to provide better support for students with learning disabilities, fostering their academic growth and social development.

Examination of Mental Health Support in the Workplace : This study could highlight the impact of mental health initiatives on employee wellbeing and productivity. It could influence organizational policies across industries, promoting the implementation of mental health programs in the workplace, ultimately leading to healthier work environments.

Evaluation of a New Cancer Treatment Method : The significance of this study could be lifesaving. The research could lead to the development of more effective cancer treatments, increasing the survival rate and quality of life for patients worldwide.

When to Write Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section is an integral part of a research proposal or a thesis. This section is typically written after the introduction and the literature review. In the research process, the structure typically follows this order:

- Title – The name of your research.

- Abstract – A brief summary of the entire research.

- Introduction – A presentation of the problem your research aims to solve.

- Literature Review – A review of existing research on the topic to establish what is already known and where gaps exist.

- Significance of the Study – An explanation of why the research matters and its potential impact.

In the Significance of the Study section, you will discuss why your study is important, who it benefits, and how it adds to existing knowledge or practice in your field. This section is your opportunity to convince readers, and potentially funders or supervisors, that your research is valuable and worth undertaking.

Advantages of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section in a research paper has multiple advantages:

- Establishes Relevance: This section helps to articulate the importance of your research to your field of study, as well as the wider society, by explicitly stating its relevance. This makes it easier for other researchers, funders, and policymakers to understand why your work is necessary and worth supporting.

- Guides the Research: Writing the significance can help you refine your research questions and objectives. This happens as you critically think about why your research is important and how it contributes to your field.

- Attracts Funding: If you are seeking funding or support for your research, having a well-written significance of the study section can be key. It helps to convince potential funders of the value of your work.

- Opens up Further Research: By stating the significance of the study, you’re also indicating what further research could be carried out in the future, based on your work. This helps to pave the way for future studies and demonstrates that your research is a valuable addition to the field.

- Provides Practical Applications: The significance of the study section often outlines how the research can be applied in real-world situations. This can be particularly important in applied sciences, where the practical implications of research are crucial.

- Enhances Understanding: This section can help readers understand how your study fits into the broader context of your field, adding value to the existing literature and contributing new knowledge or insights.

Limitations of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section plays an essential role in any research. However, it is not without potential limitations. Here are some that you should be aware of:

- Subjectivity: The importance and implications of a study can be subjective and may vary from person to person. What one researcher considers significant might be seen as less critical by others. The assessment of significance often depends on personal judgement, biases, and perspectives.

- Predictability of Impact: While you can outline the potential implications of your research in the Significance of the Study section, the actual impact can be unpredictable. Research doesn’t always yield the expected results or have the predicted impact on the field or society.

- Difficulty in Measuring: The significance of a study is often qualitative and can be challenging to measure or quantify. You can explain how you think your research will contribute to your field or society, but measuring these outcomes can be complex.

- Possibility of Overstatement: Researchers may feel pressured to amplify the potential significance of their study to attract funding or interest. This can lead to overstating the potential benefits or implications, which can harm the credibility of the study if these results are not achieved.

- Overshadowing of Limitations: Sometimes, the significance of the study may overshadow the limitations of the research. It is important to balance the potential significance with a thorough discussion of the study’s limitations.

- Dependence on Successful Implementation: The significance of the study relies on the successful implementation of the research. If the research process has flaws or unexpected issues arise, the anticipated significance might not be realized.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Survey Instruments – List and Their Uses

Future Research – Thesis Guide

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to...

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on September 24, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on March 27, 2023.

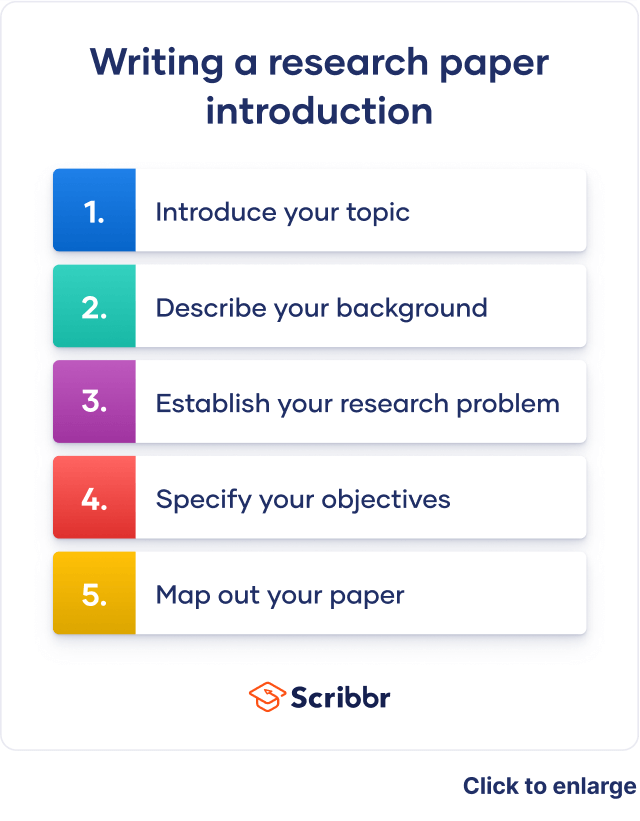

The introduction to a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your topic and get the reader interested

- Provide background or summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Detail your specific research problem and problem statement

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The introduction looks slightly different depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument by engaging with a variety of sources.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: introduce your topic, step 2: describe the background, step 3: establish your research problem, step 4: specify your objective(s), step 5: map out your paper, research paper introduction examples, frequently asked questions about the research paper introduction.

The first job of the introduction is to tell the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening hook.

The hook is a striking opening sentence that clearly conveys the relevance of your topic. Think of an interesting fact or statistic, a strong statement, a question, or a brief anecdote that will get the reader wondering about your topic.

For example, the following could be an effective hook for an argumentative paper about the environmental impact of cattle farming:

A more empirical paper investigating the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues in adolescent girls might use the following hook:

Don’t feel that your hook necessarily has to be deeply impressive or creative. Clarity and relevance are still more important than catchiness. The key thing is to guide the reader into your topic and situate your ideas.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

This part of the introduction differs depending on what approach your paper is taking.

In a more argumentative paper, you’ll explore some general background here. In a more empirical paper, this is the place to review previous research and establish how yours fits in.

Argumentative paper: Background information

After you’ve caught your reader’s attention, specify a bit more, providing context and narrowing down your topic.

Provide only the most relevant background information. The introduction isn’t the place to get too in-depth; if more background is essential to your paper, it can appear in the body .

Empirical paper: Describing previous research

For a paper describing original research, you’ll instead provide an overview of the most relevant research that has already been conducted. This is a sort of miniature literature review —a sketch of the current state of research into your topic, boiled down to a few sentences.

This should be informed by genuine engagement with the literature. Your search can be less extensive than in a full literature review, but a clear sense of the relevant research is crucial to inform your own work.

Begin by establishing the kinds of research that have been done, and end with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to respond to.

The next step is to clarify how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses.

Argumentative paper: Emphasize importance

In an argumentative research paper, you can simply state the problem you intend to discuss, and what is original or important about your argument.

Empirical paper: Relate to the literature

In an empirical research paper, try to lead into the problem on the basis of your discussion of the literature. Think in terms of these questions:

- What research gap is your work intended to fill?

- What limitations in previous work does it address?

- What contribution to knowledge does it make?

You can make the connection between your problem and the existing research using phrases like the following.

| Although has been studied in detail, insufficient attention has been paid to . | You will address a previously overlooked aspect of your topic. |

| The implications of study deserve to be explored further. | You will build on something suggested by a previous study, exploring it in greater depth. |

| It is generally assumed that . However, this paper suggests that … | You will depart from the consensus on your topic, establishing a new position. |

Now you’ll get into the specifics of what you intend to find out or express in your research paper.

The way you frame your research objectives varies. An argumentative paper presents a thesis statement, while an empirical paper generally poses a research question (sometimes with a hypothesis as to the answer).

Argumentative paper: Thesis statement

The thesis statement expresses the position that the rest of the paper will present evidence and arguments for. It can be presented in one or two sentences, and should state your position clearly and directly, without providing specific arguments for it at this point.

Empirical paper: Research question and hypothesis

The research question is the question you want to answer in an empirical research paper.

Present your research question clearly and directly, with a minimum of discussion at this point. The rest of the paper will be taken up with discussing and investigating this question; here you just need to express it.

A research question can be framed either directly or indirectly.

- This study set out to answer the following question: What effects does daily use of Instagram have on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls?

- We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls.

If your research involved testing hypotheses , these should be stated along with your research question. They are usually presented in the past tense, since the hypothesis will already have been tested by the time you are writing up your paper.

For example, the following hypothesis might respond to the research question above:

The final part of the introduction is often dedicated to a brief overview of the rest of the paper.

In a paper structured using the standard scientific “introduction, methods, results, discussion” format, this isn’t always necessary. But if your paper is structured in a less predictable way, it’s important to describe the shape of it for the reader.

If included, the overview should be concise, direct, and written in the present tense.

- This paper will first discuss several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then will go on to …

- This paper first discusses several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then goes on to …

Full examples of research paper introductions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

Are cows responsible for climate change? A recent study (RIVM, 2019) shows that cattle farmers account for two thirds of agricultural nitrogen emissions in the Netherlands. These emissions result from nitrogen in manure, which can degrade into ammonia and enter the atmosphere. The study’s calculations show that agriculture is the main source of nitrogen pollution, accounting for 46% of the country’s total emissions. By comparison, road traffic and households are responsible for 6.1% each, the industrial sector for 1%. While efforts are being made to mitigate these emissions, policymakers are reluctant to reckon with the scale of the problem. The approach presented here is a radical one, but commensurate with the issue. This paper argues that the Dutch government must stimulate and subsidize livestock farmers, especially cattle farmers, to transition to sustainable vegetable farming. It first establishes the inadequacy of current mitigation measures, then discusses the various advantages of the results proposed, and finally addresses potential objections to the plan on economic grounds.

The rise of social media has been accompanied by a sharp increase in the prevalence of body image issues among women and girls. This correlation has received significant academic attention: Various empirical studies have been conducted into Facebook usage among adolescent girls (Tiggermann & Slater, 2013; Meier & Gray, 2014). These studies have consistently found that the visual and interactive aspects of the platform have the greatest influence on body image issues. Despite this, highly visual social media (HVSM) such as Instagram have yet to be robustly researched. This paper sets out to address this research gap. We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls. It was hypothesized that daily Instagram use would be associated with an increase in body image concerns and a decrease in self-esteem ratings.

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, March 27). Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved July 23, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, writing a research paper conclusion | step-by-step guide, research paper format | apa, mla, & chicago templates, what is your plagiarism score.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Formatting a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Identify the major components of a research paper written using American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Apply general APA style and formatting conventions in a research paper.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use APA style , the documentation and formatting style followed by the American Psychological Association, as well as MLA style , from the Modern Language Association. There are a few major formatting styles used in academic texts, including AMA, Chicago, and Turabian:

- AMA (American Medical Association) for medicine, health, and biological sciences

- APA (American Psychological Association) for education, psychology, and the social sciences

- Chicago—a common style used in everyday publications like magazines, newspapers, and books

- MLA (Modern Language Association) for English, literature, arts, and humanities

- Turabian—another common style designed for its universal application across all subjects and disciplines

While all the formatting and citation styles have their own use and applications, in this chapter we focus our attention on the two styles you are most likely to use in your academic studies: APA and MLA.

If you find that the rules of proper source documentation are difficult to keep straight, you are not alone. Writing a good research paper is, in and of itself, a major intellectual challenge. Having to follow detailed citation and formatting guidelines as well may seem like just one more task to add to an already-too-long list of requirements.

Following these guidelines, however, serves several important purposes. First, it signals to your readers that your paper should be taken seriously as a student’s contribution to a given academic or professional field; it is the literary equivalent of wearing a tailored suit to a job interview. Second, it shows that you respect other people’s work enough to give them proper credit for it. Finally, it helps your reader find additional materials if he or she wishes to learn more about your topic.

Furthermore, producing a letter-perfect APA-style paper need not be burdensome. Yes, it requires careful attention to detail. However, you can simplify the process if you keep these broad guidelines in mind:

- Work ahead whenever you can. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” includes tips for keeping track of your sources early in the research process, which will save time later on.

- Get it right the first time. Apply APA guidelines as you write, so you will not have much to correct during the editing stage. Again, putting in a little extra time early on can save time later.

- Use the resources available to you. In addition to the guidelines provided in this chapter, you may wish to consult the APA website at http://www.apa.org or the Purdue University Online Writing lab at http://owl.english.purdue.edu , which regularly updates its online style guidelines.

General Formatting Guidelines

This chapter provides detailed guidelines for using the citation and formatting conventions developed by the American Psychological Association, or APA. Writers in disciplines as diverse as astrophysics, biology, psychology, and education follow APA style. The major components of a paper written in APA style are listed in the following box.

These are the major components of an APA-style paper:

Body, which includes the following:

- Headings and, if necessary, subheadings to organize the content

- In-text citations of research sources

- References page

All these components must be saved in one document, not as separate documents.

The title page of your paper includes the following information:

- Title of the paper

- Author’s name

- Name of the institution with which the author is affiliated

- Header at the top of the page with the paper title (in capital letters) and the page number (If the title is lengthy, you may use a shortened form of it in the header.)

List the first three elements in the order given in the previous list, centered about one third of the way down from the top of the page. Use the headers and footers tool of your word-processing program to add the header, with the title text at the left and the page number in the upper-right corner. Your title page should look like the following example.

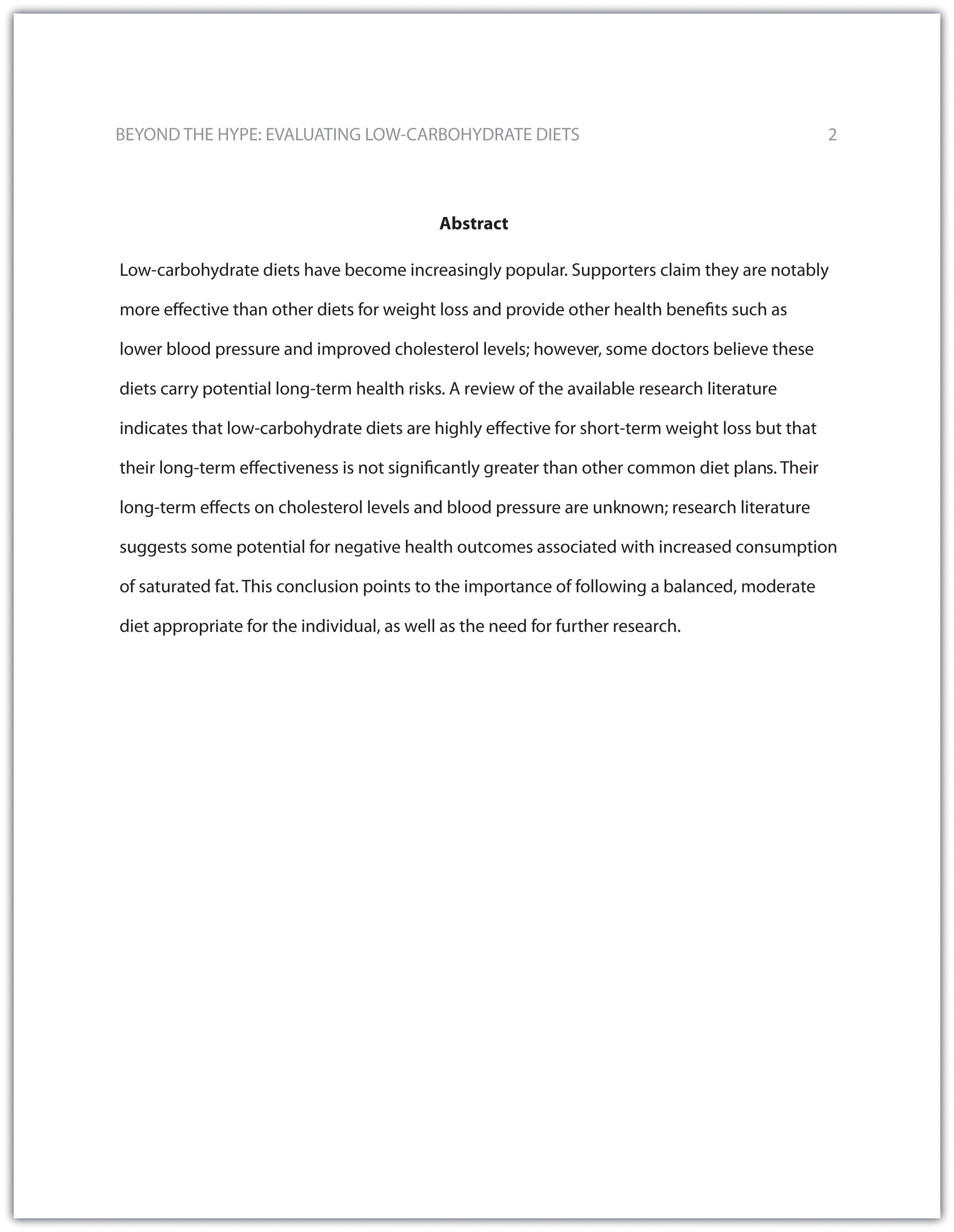

The next page of your paper provides an abstract , or brief summary of your findings. An abstract does not need to be provided in every paper, but an abstract should be used in papers that include a hypothesis. A good abstract is concise—about one hundred fifty to two hundred fifty words—and is written in an objective, impersonal style. Your writing voice will not be as apparent here as in the body of your paper. When writing the abstract, take a just-the-facts approach, and summarize your research question and your findings in a few sentences.

In Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” , you read a paper written by a student named Jorge, who researched the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets. Read Jorge’s abstract. Note how it sums up the major ideas in his paper without going into excessive detail.

Write an abstract summarizing your paper. Briefly introduce the topic, state your findings, and sum up what conclusions you can draw from your research. Use the word count feature of your word-processing program to make sure your abstract does not exceed one hundred fifty words.

Depending on your field of study, you may sometimes write research papers that present extensive primary research, such as your own experiment or survey. In your abstract, summarize your research question and your findings, and briefly indicate how your study relates to prior research in the field.

Margins, Pagination, and Headings

APA style requirements also address specific formatting concerns, such as margins, pagination, and heading styles, within the body of the paper. Review the following APA guidelines.

Use these general guidelines to format the paper:

- Set the top, bottom, and side margins of your paper at 1 inch.

- Use double-spaced text throughout your paper.

- Use a standard font, such as Times New Roman or Arial, in a legible size (10- to 12-point).

- Use continuous pagination throughout the paper, including the title page and the references section. Page numbers appear flush right within your header.

- Section headings and subsection headings within the body of your paper use different types of formatting depending on the level of information you are presenting. Additional details from Jorge’s paper are provided.

Begin formatting the final draft of your paper according to APA guidelines. You may work with an existing document or set up a new document if you choose. Include the following:

- Your title page

- The abstract you created in Note 13.8 “Exercise 1”

- Correct headers and page numbers for your title page and abstract

APA style uses section headings to organize information, making it easy for the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought and to know immediately what major topics are covered. Depending on the length and complexity of the paper, its major sections may also be divided into subsections, sub-subsections, and so on. These smaller sections, in turn, use different heading styles to indicate different levels of information. In essence, you are using headings to create a hierarchy of information.

The following heading styles used in APA formatting are listed in order of greatest to least importance:

- Section headings use centered, boldface type. Headings use title case, with important words in the heading capitalized.

- Subsection headings use left-aligned, boldface type. Headings use title case.

- The third level uses left-aligned, indented, boldface type. Headings use a capital letter only for the first word, and they end in a period.

- The fourth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are boldfaced and italicized.

- The fifth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are italicized and not boldfaced.

Visually, the hierarchy of information is organized as indicated in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” .

Table 13.1 Section Headings

| Level of Information | Text Example |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | |

| Level 2 | |

| Level 3 | |

| Level 4 | |

| Level 5 |

A college research paper may not use all the heading levels shown in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” , but you are likely to encounter them in academic journal articles that use APA style. For a brief paper, you may find that level 1 headings suffice. Longer or more complex papers may need level 2 headings or other lower-level headings to organize information clearly. Use your outline to craft your major section headings and determine whether any subtopics are substantial enough to require additional levels of headings.

Working with the document you developed in Note 13.11 “Exercise 2” , begin setting up the heading structure of the final draft of your research paper according to APA guidelines. Include your title and at least two to three major section headings, and follow the formatting guidelines provided above. If your major sections should be broken into subsections, add those headings as well. Use your outline to help you.

Because Jorge used only level 1 headings, his Exercise 3 would look like the following:

| Level of Information | Text Example |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | |

| Level 1 | |

| Level 1 | |

| Level 1 |

Citation Guidelines

In-text citations.

Throughout the body of your paper, include a citation whenever you quote or paraphrase material from your research sources. As you learned in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , the purpose of citations is twofold: to give credit to others for their ideas and to allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired. Your in-text citations provide basic information about your source; each source you cite will have a longer entry in the references section that provides more detailed information.

In-text citations must provide the name of the author or authors and the year the source was published. (When a given source does not list an individual author, you may provide the source title or the name of the organization that published the material instead.) When directly quoting a source, it is also required that you include the page number where the quote appears in your citation.

This information may be included within the sentence or in a parenthetical reference at the end of the sentence, as in these examples.

Epstein (2010) points out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Here, the writer names the source author when introducing the quote and provides the publication date in parentheses after the author’s name. The page number appears in parentheses after the closing quotation marks and before the period that ends the sentence.

Addiction researchers caution that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (Epstein, 2010, p. 137).

Here, the writer provides a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence that includes the author’s name, the year of publication, and the page number separated by commas. Again, the parenthetical citation is placed after the closing quotation marks and before the period at the end of the sentence.

As noted in the book Junk Food, Junk Science (Epstein, 2010, p. 137), “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive.”

Here, the writer chose to mention the source title in the sentence (an optional piece of information to include) and followed the title with a parenthetical citation. Note that the parenthetical citation is placed before the comma that signals the end of the introductory phrase.

David Epstein’s book Junk Food, Junk Science (2010) pointed out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Another variation is to introduce the author and the source title in your sentence and include the publication date and page number in parentheses within the sentence or at the end of the sentence. As long as you have included the essential information, you can choose the option that works best for that particular sentence and source.

Citing a book with a single author is usually a straightforward task. Of course, your research may require that you cite many other types of sources, such as books or articles with more than one author or sources with no individual author listed. You may also need to cite sources available in both print and online and nonprint sources, such as websites and personal interviews. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.2 “Citing and Referencing Techniques” and Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provide extensive guidelines for citing a variety of source types.

Writing at Work

APA is just one of several different styles with its own guidelines for documentation, formatting, and language usage. Depending on your field of interest, you may be exposed to additional styles, such as the following:

- MLA style. Determined by the Modern Languages Association and used for papers in literature, languages, and other disciplines in the humanities.

- Chicago style. Outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style and sometimes used for papers in the humanities and the sciences; many professional organizations use this style for publications as well.

- Associated Press (AP) style. Used by professional journalists.

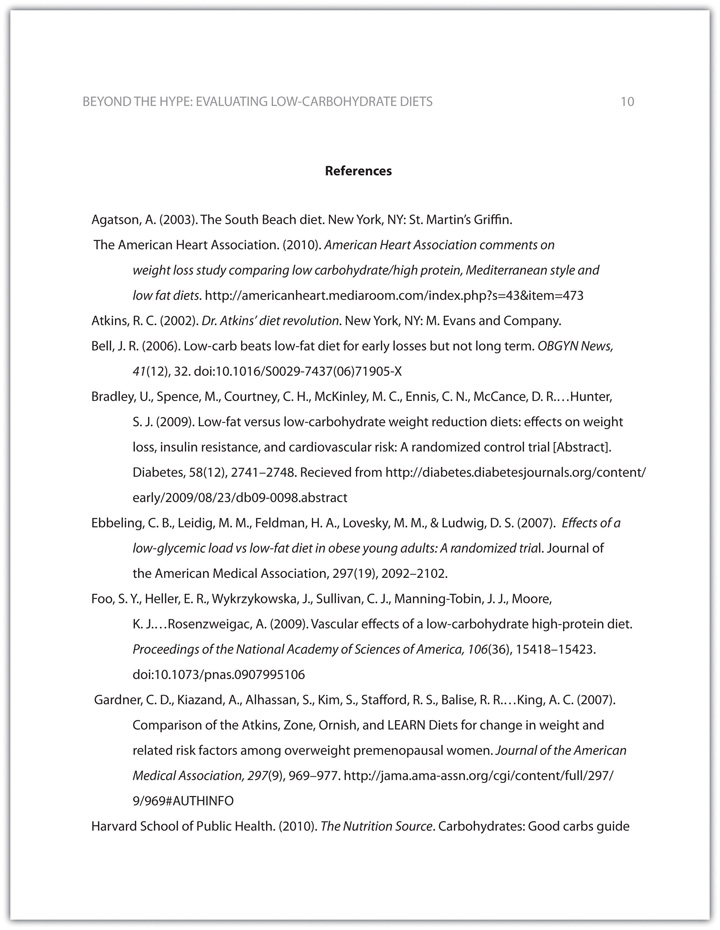

References List

The brief citations included in the body of your paper correspond to the more detailed citations provided at the end of the paper in the references section. In-text citations provide basic information—the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number if necessary—while the references section provides more extensive bibliographical information. Again, this information allows your reader to follow up on the sources you cited and do additional reading about the topic if desired.

The specific format of entries in the list of references varies slightly for different source types, but the entries generally include the following information:

- The name(s) of the author(s) or institution that wrote the source

- The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

- The full title of the source

- For books, the city of publication

- For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

- For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

- For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

The references page is double spaced and lists entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If an entry continues for more than one line, the second line and each subsequent line are indented five spaces. Review the following example. ( Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provides extensive guidelines for formatting reference entries for different types of sources.)

In APA style, book and article titles are formatted in sentence case, not title case. Sentence case means that only the first word is capitalized, along with any proper nouns.

Key Takeaways

- Following proper citation and formatting guidelines helps writers ensure that their work will be taken seriously, give proper credit to other authors for their work, and provide valuable information to readers.

- Working ahead and taking care to cite sources correctly the first time are ways writers can save time during the editing stage of writing a research paper.

- APA papers usually include an abstract that concisely summarizes the paper.

- APA papers use a specific headings structure to provide a clear hierarchy of information.

- In APA papers, in-text citations usually include the name(s) of the author(s) and the year of publication.

- In-text citations correspond to entries in the references section, which provide detailed bibliographical information about a source.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:07 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Board Members

- Management Team

- Become a Contributor

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Code of Ethical Practices

KNOWLEDGE NETWORK

- Search Engines List

- Suggested Reading Library

- Web Directories

- Research Papers

- Industry News

- Become a Member

- Associate Membership

- Certified Membership

- Membership Application

- Corporate Application

- CIRS Certification Program

- CIRS Certification Objectives

- CIRS Certification Benefits

- CIRS Certification Exam

- Maintain Your Certification

- Upcoming Events

- Live Classes

- Classes Schedule

- Webinars Schedules

- Latest Articles

- Internet Research

- Search Techniques

- Research Methods

- Business Research

- Search Engines

- Research & Tools

- Investigative Research

- Internet Search

- Work from Home

- Internet Ethics

- Internet Privacy

Six Reasons Why Research is Important

Everyone conducts research in some form or another from a young age, whether news, books, or browsing the Internet. Internet users come across thoughts, ideas, or perspectives - the curiosity that drives the desire to explore. However, when research is essential to make practical decisions, the nature of the study alters - it all depends on its application and purpose. For instance, skilled research offered as a research paper service has a definite objective, and it is focused and organized. Professional research helps derive inferences and conclusions from solving problems. visit the HB tool services for the amazing research tools that will help to solve your problems regarding the research on any project.

What is the Importance of Research?

The primary goal of the research is to guide action, gather evidence for theories, and contribute to the growth of knowledge in data analysis. This article discusses the importance of research and the multiple reasons why it is beneficial to everyone, not just students and scientists.

On the other hand, research is important in business decision-making because it can assist in making better decisions when combined with their experience and intuition.

Reasons for the Importance of Research

- Acquire Knowledge Effectively

- Research helps in problem-solving

- Provides the latest information

- Builds credibility

- Helps in business success

- Discover and Seize opportunities

1- Acquire Knowledge Efficiently through Research

The most apparent reason to conduct research is to understand more. Even if you think you know everything there is to know about a subject, there is always more to learn. Research helps you expand on any prior knowledge you have of the subject. The research process creates new opportunities for learning and progress.

2- Research Helps in Problem-solving

Problem-solving can be divided into several components, which require knowledge and analysis, for example, identification of issues, cause identification, identifying potential solutions, decision to take action, monitoring and evaluation of activity and outcomes.

You may just require additional knowledge to formulate an informed strategy and make an informed decision. When you know you've gathered reliable data, you'll be a lot more confident in your answer.

3- Research Provides the Latest Information

Research enables you to seek out the most up-to-date facts. There is always new knowledge and discoveries in various sectors, particularly scientific ones. Staying updated keeps you from falling behind and providing inaccurate or incomplete information. You'll be better prepared to discuss a topic and build on ideas if you have the most up-to-date information. With the help of tools and certifications such as CIRS , you may learn internet research skills quickly and easily. Internet research can provide instant, global access to information.

4- Research Builds Credibility

Research provides a solid basis for formulating thoughts and views. You can speak confidently about something you know to be true. It's much more difficult for someone to find flaws in your arguments after you've finished your tasks. In your study, you should prioritize the most reputable sources. Your research should focus on the most reliable sources. You won't be credible if your "research" comprises non-experts' opinions. People are more inclined to pay attention if your research is excellent.

5- Research Helps in Business Success

R&D might also help you gain a competitive advantage. Finding ways to make things run more smoothly and differentiate a company's products from those of its competitors can help to increase a company's market worth.

6- Research Discover and Seize Opportunities

People can maximize their potential and achieve their goals through various opportunities provided by research. These include getting jobs, scholarships, educational subsidies, projects, commercial collaboration, and budgeted travel. Research is essential for anyone looking for work or a change of environment. Unemployed people will have a better chance of finding potential employers through job advertisements or agencies.

How to Improve Your Research Skills

Start with the big picture and work your way down.

It might be hard to figure out where to start when you start researching. There's nothing wrong with a simple internet search to get you started. Online resources like Google and Wikipedia are a great way to get a general idea of a subject, even though they aren't always correct. They usually give a basic overview with a short history and any important points.

Identify Reliable Source

Not every source is reliable, so it's critical that you can tell the difference between the good ones and the bad ones. To find a reliable source, use your analytical and critical thinking skills and ask yourself the following questions: Is this source consistent with other sources I've discovered? Is the author a subject matter expert? Is there a conflict of interest in the author's point of view on this topic?

Validate Information from Various Sources

Take in new information.

The purpose of research is to find answers to your questions, not back up what you already assume. Only looking for confirmation is a minimal way to research because it forces you to pick and choose what information you get and stops you from getting the most accurate picture of the subject. When you do research, keep an open mind to learn as much as possible.

Facilitates Learning Process

Learning new things and implementing them in daily life can be frustrating. Finding relevant and credible information requires specialized training and web search skills due to the sheer enormity of the Internet and the rapid growth of indexed web pages. On the other hand, short courses and Certifications like CIRS make the research process more accessible. CIRS Certification offers complete knowledge from beginner to expert level. You can become a Certified Professional Researcher and get a high-paying job, but you'll also be much more efficient and skilled at filtering out reliable data. You can learn more about becoming a Certified Professional Researcher.

Stay Organized

You'll see a lot of different material during the process of gathering data, from web pages to PDFs to videos. You must keep all of this information organized in some way so that you don't lose anything or forget to mention something properly. There are many ways to keep your research project organized, but here are a few of the most common: Learning Management Software , Bookmarks in your browser, index cards, and a bibliography that you can add to as you go are all excellent tools for writing.

Make Use of the library's Resources

If you still have questions about researching, don't worry—even if you're not a student performing academic or course-related research, there are many resources available to assist you. Many high school and university libraries, in reality, provide resources not only for staff and students but also for the general public. Look for research guidelines or access to specific databases on the library's website. Association of Internet Research Specialists enjoys sharing informational content such as research-related articles , research papers , specialized search engines list compiled from various sources, and contributions from our members and in-house experts.

of Conducting Research

Latest from erin r. goodrich.

- Enhancing Efficiency: The Role of Technology in Personal Injury Case Management

- The Evolution and Future of Workplace Benefit Administration

- 10 Best People Search Engines and Websites in 2022

Live Classes Schedule

- JUN 14 CIRS Certification Internet Research Training Program Live Classes Online

World's leading professional association of Internet Research Specialists - We deliver Knowledge, Education, Training, and Certification in the field of Professional Online Research. The AOFIRS is considered a major contributor in improving Web Search Skills and recognizes Online Research work as a full-time occupation for those that use the Internet as their primary source of information.

Get Exclusive Research Tips in Your Inbox

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Advertising Opportunities

- Knowledge Network

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Animal Research

- Cardiovascular/Pulmonary

- Health Services

- Health Policy

- Health Promotion

- History of Physical Therapy

- Implementation Science

- Integumentary

- Musculoskeletal

- Orthopedics

- Pain Management

- Pelvic Health

- Pharmacology

- Population Health

- Professional Issues

- Psychosocial

- Advance Articles

- PTJ Peer Review Academies

- Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Why Publish With PTJ?

- Open Access

- Call for Papers

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Promote your Article

- About Physical Therapy

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Permissions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Author contributions, disclosures.

- < Previous

How Should We Determine the Importance of Research?

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

D U Jette, How Should We Determine the Importance of Research?, Physical Therapy , Volume 98, Issue 3, March 2018, Pages 149–152, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx119

- Permissions Icon Permissions

For scientific and professional journals, the publication of research papers that are important and have potentially significant impact is a multifactorial quest. The first step is attracting authors/researchers who are publishing work that is impactful. Editorial boards, such as that of PTJ , have continual conversations about how to attract excellent researchers to publish in their journals. At the same time, higher education institutions in which many authors are employed continue to emphasize research productivity when evaluating faculty performance. 1 , 2 This fact motivates authors to submit manuscripts to what they perceive to be the highest-quality journals. 3 Evaluation of research quality influences who has a career in academia as well as where researchers publish and which journals succeed. 4 Assessing the situation, Altbach remarked, “Universities are engaged in a global arms race of publication: and the academics are the shock troops of the struggle.” 5 (p6) One reason for the added emphasis on research is that research increases visibility of an institution and, therefore, its prestige. 6 More funding flows to universities with prestigious, top-ranked research profiles. 2 , 5 Institutions also emphasize research prestige to attract better students and faculty, thus further bolstering their reputations.

The quest to hire, promote, and retain faculty who bring prestige to the institution in the form of research encourages institutions to measure research recognition. Terms describing the necessary attributes of research contributions for institutional promotion and tenure decisions include excellence, importance and significance, 2 substantiveness, 7 and impact. 8 Assessment of these attributes by hiring and promotion committees is based to some extent on the number of scholarly “products” and their rate of production, whether a product is peer reviewed, the number of citations of the work, numeric ratings of the journals in which work appears, and the general reputation of the journal or publisher among professional peers. 9 Review for promotion and tenure also often includes evaluation of candidates’ research by peers outside of their home institution with like expertise. Peers are asked to comment on the quality of the candidate's research and its impact on the field. 10 Although they may have a better perspective on whether a candidate's work has had an impact on their field, external reviewers are likely to assess the quality of publications by using metrics similar to the institutional review committee, perhaps with more knowledge of the best-known journals in their field.

One common indicator used by institutional review committees to determine qualities such as excellence, impact, or importance is the journal impact factor (JIF). 9 The JIF relies on citation numbers over a relatively short period of time and has well-known limitations. 11 The JIF was originally designed to help librarians decide which journals to buy and has subsequently, and perhaps inappropriately, been used as a surrogate for the quality of individual papers and individual researchers’ scholarship. 12 Other indices such as the h-index are also commonly, and more appropriately, applied at the individual level; however the h-index also is a measure based on numbers of citations. Because authors are driven by the performance expectations and the reward systems at their institutions, 8 they are likely to seek journals with reputations for publishing high-value and frequently cited work, that is, journals with a high JIF. Alberts, 13 editor-in-chief of Science in 2013, noted that this tendency has led to researchers submitting inappropriate papers to highly cited journals so as to “gain points” when being evaluated, and also to journal bias against accepting papers that might not be highly cited. In addition, traditional metrics such as JIF may deter faculty from pursuing anything but the scholarship of discovery 9 and may be detrimental to review of junior faculty because of time lags in publication and citation. 14