Methodological Approaches to Literature Review

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 09 May 2023

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Dennis Thomas 2 ,

- Elida Zairina 3 &

- Johnson George 4

503 Accesses

1 Citations

The literature review can serve various functions in the contexts of education and research. It aids in identifying knowledge gaps, informing research methodology, and developing a theoretical framework during the planning stages of a research study or project, as well as reporting of review findings in the context of the existing literature. This chapter discusses the methodological approaches to conducting a literature review and offers an overview of different types of reviews. There are various types of reviews, including narrative reviews, scoping reviews, and systematic reviews with reporting strategies such as meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Review authors should consider the scope of the literature review when selecting a type and method. Being focused is essential for a successful review; however, this must be balanced against the relevance of the review to a broad audience.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Akobeng AK. Principles of evidence based medicine. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(8):837–40.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alharbi A, Stevenson M. Refining Boolean queries to identify relevant studies for systematic review updates. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(11):1658–66.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Article Google Scholar

Aromataris E MZE. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. 2020.

Google Scholar

Aromataris E, Pearson A. The systematic review: an overview. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(3):53–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Aromataris E, Riitano D. Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence. A guide to the literature search for a systematic review. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(5):49–56.

Babineau J. Product review: covidence (systematic review software). J Canad Health Libr Assoc Canada. 2014;35(2):68–71.

Baker JD. The purpose, process, and methods of writing a literature review. AORN J. 2016;103(3):265–9.

Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 2010;7(9):e1000326.

Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, Franco OH. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):1–12.

Brown D. A review of the PubMed PICO tool: using evidence-based practice in health education. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(4):496–8.

Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 4: methods for assessing evidence on intervention implementation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:59–69.

Cook DJ, Mulrow CD, Haynes RB. Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(5):376–80.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(5):380–7.

Cummings SR, Browner WS, Hulley SB. Conceiving the research question and developing the study plan. In: Cummings SR, Browner WS, Hulley SB, editors. Designing Clinical Research: An Epidemiological Approach. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): P Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. p. 14–22.

Eriksen MB, Frandsen TF. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: a systematic review. JMLA. 2018;106(4):420.

Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing. 2015;24(4):230–5.

Flemming K, Booth A, Hannes K, Cargo M, Noyes J. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 6: reporting guidelines for qualitative, implementation, and process evaluation evidence syntheses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:79–85.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5(3):101–17.

Gregory AT, Denniss AR. An introduction to writing narrative and systematic reviews; tasks, tips and traps for aspiring authors. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(7):893–8.

Harden A, Thomas J, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 5: methods for integrating qualitative and implementation evidence within intervention effectiveness reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:70–8.

Harris JL, Booth A, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 2: methods for question formulation, searching, and protocol development for qualitative evidence synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:39–48.

Higgins J, Thomas J. In: Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3, updated February 2022). Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.: Cochrane; 2022.

International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO). Available from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ .

Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(3):118–21.

Landhuis E. Scientific literature: information overload. Nature. 2016;535(7612):457–8.

Lockwood C, Porritt K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, Loveday H, Carrier J, Stannard D. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global . https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-03 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Lorenzetti DL, Topfer L-A, Dennett L, Clement F. Value of databases other than medline for rapid health technology assessments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2014;30(2):173–8.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for (SR) and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;6:264–9.

Mulrow CD. Systematic reviews: rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309(6954):597–9.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Munthe-Kaas HM, Glenton C, Booth A, Noyes J, Lewin S. Systematic mapping of existing tools to appraise methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative research: first stage in the development of the CAMELOT tool. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):1–13.

Murphy CM. Writing an effective review article. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(2):89–90.

NHMRC. Guidelines for guidelines: assessing risk of bias. Available at https://nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/develop/assessing-risk-bias . Last published 29 August 2019. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 1: introduction. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018b;97:35–8.

Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, et al. Cochrane qualitative and implementation methods group guidance series – paper 3: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018a;97:49–58.

Noyes J, Booth A, Moore G, Flemming K, Tunçalp Ö, Shakibazadeh E. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(Suppl 1):e000893.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Healthcare. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Polanin JR, Pigott TD, Espelage DL, Grotpeter JK. Best practice guidelines for abstract screening large-evidence systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(3):330–42.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):1–7.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Brit Med J. 2017;358

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J. 2016;355

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Tawfik GM, Dila KAS, Mohamed MYF, et al. A step by step guide for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis with simulation data. Trop Med Health. 2019;47(1):1–9.

The Critical Appraisal Program. Critical appraisal skills program. Available at https://casp-uk.net/ . 2022. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

The University of Melbourne. Writing a literature review in Research Techniques 2022. Available at https://students.unimelb.edu.au/academic-skills/explore-our-resources/research-techniques/reviewing-the-literature . Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

The Writing Center University of Winconsin-Madison. Learn how to write a literature review in The Writer’s Handbook – Academic Professional Writing. 2022. Available at https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/reviewofliterature/ . Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Thompson SG, Sharp SJ. Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med. 1999;18(20):2693–708.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):15.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Yoneoka D, Henmi M. Clinical heterogeneity in random-effect meta-analysis: between-study boundary estimate problem. Stat Med. 2019;38(21):4131–45.

Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Systematic reviews: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(5):1086–92.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre of Excellence in Treatable Traits, College of Health, Medicine and Wellbeing, University of Newcastle, Hunter Medical Research Institute Asthma and Breathing Programme, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

Dennis Thomas

Department of Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Elida Zairina

Centre for Medicine Use and Safety, Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Johnson George

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Johnson George .

Section Editor information

College of Pharmacy, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Derek Charles Stewart

Department of Pharmacy, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, United Kingdom

Zaheer-Ud-Din Babar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Thomas, D., Zairina, E., George, J. (2023). Methodological Approaches to Literature Review. In: Encyclopedia of Evidence in Pharmaceutical Public Health and Health Services Research in Pharmacy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50247-8_57-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50247-8_57-1

Received : 22 February 2023

Accepted : 22 February 2023

Published : 09 May 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-50247-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-50247-8

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Biomedicine and Life Sciences Reference Module Biomedical and Life Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Methodology

- Open access

- Published: 13 October 2014

Considering methodological options for reviews of theory: illustrated by a review of theories linking income and health

- Mhairi Campbell 1 ,

- Matt Egan 2 ,

- Theo Lorenc 3 ,

- Lyndal Bond 4 ,

- Frank Popham 1 ,

- Candida Fenton 1 &

- Michaela Benzeval 1 , 5

Systematic Reviews volume 3 , Article number: 114 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

40 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Review of theory is an area of growing methodological advancement. Theoretical reviews are particularly useful where the literature is complex, multi-discipline, or contested. It has been suggested that adopting methods from systematic reviews may help address these challenges. However, the methodological approaches to reviews of theory, including the degree to which systematic review methods can be incorporated, have received little discussion in the literature. We recently employed systematic review methods in a review of theories about the causal relationship between income and health.

This article discusses some of the methodological issues we considered in developing the review and offers lessons learnt from our experiences. It examines the stages of a systematic review in relation to how they could be adapted for a review of theory. The issues arising and the approaches taken in the review of theories in income and health are considered, drawing on the approaches of other reviews of theory.

Different approaches to searching were required, including electronic and manual searches, and electronic citation tracking to follow the development of theories. Determining inclusion criteria was an iterative process to ensure that inclusion criteria were specific enough to make the review practical and focused, but not so narrow that key literature was excluded. Involving subject specialists was valuable in the literature searches to ensure principal papers were identified and during the inductive approaches used in synthesis of theories to provide detailed understanding of how theories related to another. Reviews of theory are likely to involve iterations and inductive processes throughout, and some of the concepts and techniques that have been developed for qualitative evidence synthesis can be usefully translated to theoretical reviews of this kind.

Conclusions

It may be useful at the outset of a review of theory to consider whether the key aim of the review is to scope out theories relating to a particular issue; to conduct in-depth analysis of key theoretical works with the aim of developing new, overarching theories and interpretations; or to combine both these processes in the review. This can help decide the most appropriate methodological approach to take at particular stages of the review.

Peer Review reports

Theory is fundamental to research and rational thought. The term ‘theory’ has been variously defined, and is frequently used without definition, but often refers to an explanatory framework for observations. In science, theories generally purport to explain empirical observations and form the basis on which testable hypotheses are generated to provide support for, or challenge, the theory. Gorelick defines theory as ‘the creative, inductive, and synthetic discipline of forming hypotheses’ [ 1 ], p. 7. Popper defined a scientific theory as one that is experimentally falsifiable [ 2 ]. Merton has contrasted ‘grand’ social theories such as Marxism, functionalism, and post-modernism with ‘middle-range theories’ that start with an empirical phenomenon and abstract from it to create general statements that can be verified by data [ 3 ]. Mid-range theories are dominant within empirical and scientific approaches to research. Gough usefully categorises such research as aiming to generate, explore, or test theories. Of particular importance in health literature are studies which include theories about cause and effect; such studies may test these theories in a ‘black box’ way or attempt to generate, explore, and test more clearly articulated causal-pathway frameworks, such as those presented in logic models [ 4 ]. For this discussion, the terms ‘causal pathway’, ‘causal maps’, and ‘logic model’ refer to qualitative models used to identify key concepts and the links between them [ 5 ].

Within the health sciences, it is widely understood that individual and population health are influenced by a wide array of interconnecting factors, so theoretical models can be complex and, at times, contested [ 6 ]. However, different disciplines approach such research in different ways and are not always well connected. Reviews of theory may aid our attempts to navigate a diverse literature and potentially lead to insights into how factors relate to one another [ 6 – 9 ]. Theory reviews could have one or more of the following aims: identifying and mapping a comprehensive range of relevant theories; assessing which theories have become influential and which have been, or have become over time, largely overlooked; and integrating complementary theories and facilitating the analysis and synthesis of theories into more generalised or abstract ‘meta-theories’. By focusing on theory, rather than diverse empirical studies, reviews can be useful devices to describe complex topics across different disciplines and inform policy debates.

The purpose of this article is to consider the ways in which theoretical reviews might be conducted and in particular the role of systematic approaches within this. It illustrates the discussion by drawing on the approach of a recent theoretical review the authors undertook of income and health [ 10 ]. It discusses some of the methodological challenges and options that reviewers may face when planning and conducting reviews that focus on theoretical literature. We think the discussion will be particularly relevant to reviewers considering the degree to which they might attempt to use and adapt methods commonly associated with systematic reviews, which tend to have been developed around reviews of empirical research and thus not specifically designed to assess descriptions of theories underpinning research. We will discuss the extent to which methods developed and used for reviews of empirical research may, or indeed may not, be usefully adapted to meet the challenges posed when reviewing theories on the phenomena of interest. In particular, we will discuss some of the methods we (the authors) employed when conducting our own recent review of theories of income and health [ 10 ]. Reviews of theory are part of a growing methodological advancement, and we think this would be an opportune time to contribute lessons learnt from our project and others and discuss some of the methodological considerations that inform such a review. Some of our reflections are based on the methods we employed in our review; others result from critical thinking and discussions that took place following the review’s completion.

Below, we outline general approaches in the literature to conducting reviews of theories. We then describe the broad principles of our approach before providing a detailed summary of each stage of the review and the way in which we incorporated systematic approaches into them. We examine how this contributed to our understanding of the literature on income and health and reflect on the value of this approach.

Existing approaches to reviews of theory

There is often substantial variation in the methodologies of reviews that consider theory. Some take the form of traditional literature reviews, often reliant on expert knowledge in the relevant field. Such expert knowledge allows in-depth understanding of theories and links between them. However, it can be limited to the disciplinary perspective of the reviewer, not necessarily identifying less popular or emerging theories, and cannot provide a sense of the extent to which different theories are employed in the literature. Given these limitations, some reviewers of theory have employed methodologies associated with systematic reviews such as comprehensive searches and clear criteria for including, appraising, and synthesising the literature to provide a more comprehensive picture [ 11 , 12 ]. Reviews of theory are thus rather different to reviews of empirical data. In particular, the primary goal of using systematic methods in the latter case is to minimise bias. In theory reviews—where it is not even clear that the concept of ‘bias’ is substantively meaningful—their main contribution may be more in ‘opening up’ reviewers’ thinking about the research topic and widening the potential space of hypothesis generation.

Often reviews of theory are conducted to assist reviewers involved in carrying out systematic reviews of intervention effectiveness. Realist review [ 13 , 14 ] is currently a key area of methodological development around the integration of theory into reviews of interventions. Realist reviews aim to draw out and test ‘programme theories’ about the causal pathways through which interventions work, in order to bring together evidence on effectiveness with data on implementation and context. In some cases, theory reviews may have relatively narrow inclusion criteria tied to theories about a specific intervention. However, narrow criteria do not necessarily lead to small-scale review. Two systematic reviews of theory conducted in relation to larger reviews are Baxter and Allmark’s [ 12 ] review of chest pain and medical assistance and Bonell et al.’s [ 11 ] review of theories on school environment and health: the former has a narrower research question with a search result of around 100 papers, but the latter entailed screening more than 62,000 papers.

A recent systematic review of interventions on crime, fear of crime, health, and the environment was preceded by a mapping broad review of theories that attempted to explain associations between these factors [ 5 ]. The crime review used a pragmatic approach to searching and selecting literature and did not attempt to provide a comprehensive systematic review of all theories related to the topic. Rather, the theory review aimed to construct a coherent framework for integrating relevant theories, in order to contextualise and better understand the empirical data.

The income and health review of theory

We conducted a review of theories about causal relationships between income and health (see Additional file 1 for brief description). Given the wide-ranging literatures across disciplines, and the contested nature of many debates, we felt that a systematic approach to the review would help shed light on the range of casual paths that had been posited. Our intention was to gain some of the benefits of applying systematic review methods to a review of theory, such as clarity, comprehensiveness, and transparency. By making the literature search as systematic and transparent as possible, a review can extend beyond researcher knowledge and disciplinary background [ 15 ]. Developing inclusion criteria and devising methods to uniformly capture data across included papers strengthens objectivity [ 15 ]. By the time the included papers have been assessed, it is hoped that the explicit methods used reduce subjectivity. Once the theories are gathered through the systematic searching, screening, and extracting, the interpretation of their content at the synthesis stage may be still be at risk of subjectivity.

Reviews of theory may be particularly valuable in seeking to develop a synoptic understanding of questions where a number of different disciplines overlap. In our recent review of theories describing pathways linking individual and family income to health [ 10 ], we included theories from public health, psychology, social policy, sociology, and economics, all of which have distinct traditions and vocabularies. In addition, many of the causal pathways between income and health described by these theories are long and complex. In cases such as these, syntheses of theory can help to produce new insights about complex fields by drawing together different paradigms and translating concepts between disciplines.

The techniques developed in the crime theory review were adapted by the authors of the present article for a review of theories linking income to health across the lifecourse [ 10 ]. In the income and health review, an attempt was made to incorporate more techniques from systematic reviews, including a priori inclusion criteria, comprehensive electronic searching, and standardised data extraction. These methods were employed to capture theories from literature in disciplines with which we may have been less familiar. The methods used for our review are indebted to those developed by realist reviewers. However, our review focused less specifically on evaluating mid-range theories of the mechanisms and contexts of interventions and more on mapping and synthesising the whole landscape of theories around income, health, and the lifecourse. The resulting review was a methodological hybrid including elements of the earlier crime review, drawing on seminal literature to create a framework, and more standard systematic reviews. Below, we outline key review stages, illustrated by the methods used in the income and health review of theory. Challenges faced and tactics to address, these are described. The aim was to generate guidance and discussion of methods that may be useful when planning and conducting a review of theory.

Results and discussion

Developing the research question.

An explicitly stated research question is a characteristic of systematic reviews that can be adopted for reviews of theory. The question should be designed following consideration of what the end users will find useful, so consultations with potential end users may be part of the process [ 15 ]. As stated above, review questions can be broad or narrow in scope. A broad question may reflect the reviewers’ aim to scope out and map a wide range of theories within a subject area. The purpose of this income and health review was to use theory as a tool to support a larger programme of work exploring the importance of income and other aspects of family resources in determining a wide range of health and social outcomes. In contrast, if the aim is to identify theories relating to a specific phenomenon or intervention, then a narrow question may be more appropriate. For example, the review of theories of behaviour change in limiting gestational weight gain [ 16 ]; and in another review, Sherman et al. [ 17 ] used self regulatory theory to examine psychological adjustment among male partners in response to women’s cancer. Both these reviews of theory have a narrow topic, distinct from the broad scope of the income and health review.

Assembling the team

Guidance for conducting a systematic review recommends gathering a team that includes an experienced reviewer, a subject specialist, and an information scientist with advanced knowledge of bibliographic search strategies [ 15 ], p. 85; [ 18 ]. For theory reviews, the role of the subject specialists and the stages at which their contribution is valuable may become particularly crucial. Besides helping to ensure that key papers within the field are identified for inclusion in the review, specialists can provide a detailed understanding of how different theories came to be developed, how one theory relates to another, and where the points of controversy lie. It may be useful to have input from more than one specialist if the scope of the review is multi-disciplinary or covers a subject area that is divided by rival theoretical ‘camps’. Conducting the income and health review was aided by the team including members with experience of systematic reviews, theory reviews, and information science, as well as reviewers with backgrounds in lifecourse epidemiology, social policy, and economics. We also worked with an advisory group that included end users and researchers with a range of experience in social science research.

The degree of specialist input required will be influenced by the depth of analysis required. Reviews that aim to provide in-depth synthesis, including attempts to develop meta-theories, are likely to require greater specialist input than reviews that aim to scope the various theories in the literature. This echoes guidance for other types of review. For example, Cochrane’s Qualitative and Implementation Methods group states that greater subject expertise is required to appraise the theoretical contributions made by qualitative research compared to that required simply to include or exclude relevant evidence [ 19 ]. Hence, the most appropriate team for any particular review will depend not only on the subject matter being reviewed, but also on the degree to which the review is intended primarily to be a scoping exercise or a more specialist theoretical analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion

A priori inclusion and exclusion criteria are a mainstay of systematic reviews, helping to guide the literature search and ensure clear focus and transparency in the selection of studies. Frameworks for developing such criteria have been developed. For example, Cochrane advocates the use of criteria that specifies population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study (PICOS) design. Qualitative reviewers have an alternative framework: sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, and research type (SPIDER) [ 20 ]. No comparable frameworks currently exist for theory reviews. When conducting reviews of theory, the task of creating inclusion/exclusion criteria can present challenges. First, the term ‘theory’ needs to be defined with enough precision to enable reviewers to consistently filter out papers that are insufficiently theoretical. Generic definitions, such as those highlighted at the beginning of this article, are conceptually helpful, but in practice, reviewers may find themselves struggling to decide whether a text is describing a theory or a hypothesis or speculation (and wondering how crucial these distinctions might be for the review). They may also struggle to find a consistent way of distinguishing a general discussion of issues from a more fully expounded theory. The decisions that were taken of includable theory during the income and health review were guided by screening for substantial hypothesis of exposure—mechanism—outcome and study design. We found considering papers in relation to these criteria a useful tool to clarify the theory content of papers, although we would emphasise that in this particular example it is theories of cause and effect that is being examined. Reviews of alternative types of theory would require alternative criteria.

A second challenge relates to the tension between having inclusion criteria that are specific enough to make the review practical and focused, but not so specific that key literature is excluded. Although this issue is not exclusive to reviews of theory, we found that a particular problem with the income and health theory review was that some of the most widely recognised theoretical texts did not originate from literature that focused on income, health, or lifecourse (i.e. not all three of these elements simultaneously) specifically. The Black Report [ 21 ], for instance, continues to exert a huge influence on how researchers think about the causes of health inequalities, and its theoretical framework can be seen to underpin some of the literature that was relevant to our review. However, the Black Report itself generally refers to the broader concept of socio-economic status rather than more specifically to the issue of income. We did not want to exclude the theoretical framework outlined in the Black Report nor did we want to open up our inclusion criteria so that it included all theories of socio-economic status and health (to do so would have been an enormous undertaking).

One potential solution to both these challenges is to acknowledge that overly rigid a priori inclusion criteria may be less useful for theory reviews, whilst more subjective methods of selecting relevant studies may be more useful; what may be required is a careful balance between these approaches. In the income and health review we developed inclusion criteria in advance of the review but acknowledged that there could be some papers key to explaining relevant theories that might be missed and therefore we allowed reviewers some leeway to include papers that did not quite fit the criteria if deemed sufficiently relevant. Subjective appraisals for relevance should ideally be conducted independently by more than one reviewer reading each text and, if necessary, resolving disagreements through discussion and/or an additional reviewer’s input. However, this process can be time consuming and resource intensive if a literature search has identified large numbers of potentially relevant papers. Another solution could be to use a second reviewer to independently check a random sample of included papers to verify that the criteria are being met consistently. Reviewers may also choose to modify inclusion criteria as the review progresses so that apparent gaps can be redressed and points of interest can be pursued in more detail [ 18 ]. Whilst potentially useful, these ‘solutions’ all carry possible risks of their own related to subjective bias, transparency, size, scope, and manageability of the review.

Our own ‘solution’ to the challenge of determining inclusion criteria was a pragmatic combination of approaches. Two of the review authors (MB, FP) with expert knowledge of socio-economics and income-health literature were able to identify ‘seminal’ papers (key texts, widely regarded as theoretically influential within the field) which are often cited as making important advances in the understanding of how socio-economic factors and health are related. The number of papers included at that stage was small, but the inclusion criteria were broad in the sense that we included theories that considered socio-economic status broadly rather than the narrow definition of income alone. From this review, we created a conceptual framework within which to structure a more in-depth review. A second stage of the review sought out wide-ranging literatures from different disciplines with theories that related specifically to income, health, and lifecourse (or life stages). For this second stage, we developed a priori criteria which were modified slightly as the review progressed. In addition for this stage, we developed criteria for identifying theory based broadly on Pawson and Tilley’s [ 22 ] concepts of context, mechanism, and outcome; although as noted above, the aim of our review was broader than most realist reviews and not focused on evaluation. To be included, a theory had to describe a causal association connecting income to health through a specific pathway or mechanism. More complex theories (e.g. those that involve multiple and multi-staged pathways and outcomes, feedback loops, contextual factors) were included if they involved the three core components of income, causal pathway or mechanism, and health outcome. Papers were excluded if they did not discuss theories at all or if they did not present theories containing all three of the core components. Papers were also excluded if the theoretical discussion was judged (subjectively) by reviewers to be cursory, for example, where a hypothesis or existing theory was briefly referred to or implied as part of a general discussion.

Literature searches for systematic reviews often incorporate formal electronic searches of subject-relevant research databases such as MEDLINE, EconLit, and PsycINFO. It is also good practice to include so-called ‘hand searching’ (a misnomer, as much of this searching is also electronic) techniques. Hand searching may include expert consultations, trawls through specific journals, checking the references of included studies, and seeing where included studies have themselves been cited (some databases such as Web of Knowledge and Scopus allow for this type of forward citation tracking) [ 15 ], p. 104.

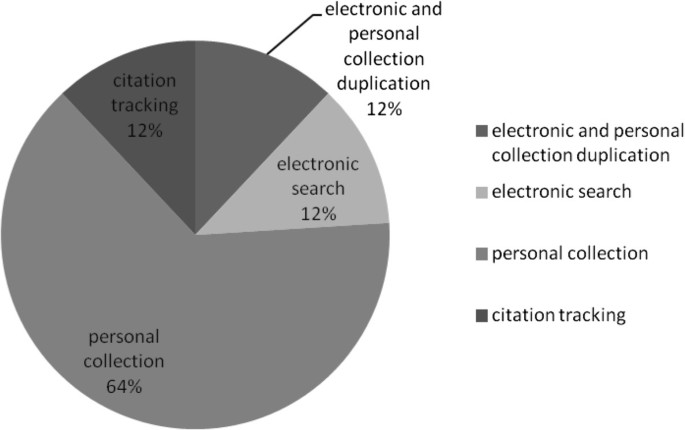

In our review of income and health, the aim of the electronic searches was to identify papers outwith our personal collections. The intentionally broad focus of the review question, combined with the vast amount of literature relating to income and health, resulted in our development of a two part electronic search strategy (see Additional file 2 ). One focused on ‘highly cited literature’ and the other aimed to capture ‘recent literature’, although both employed the same search terms. The highly cited search was an attempt to identify the most influential theoretical work. This used electronic databases, SCOPUS and Web of Knowledge, which focus on high impact journals and may be used for citation tracking. The top 2,000 papers, ordered by number of citations, were taken from each database, on the assumption that the most highly cited papers were most likely to have been particularly influential. This search was repeated twice as we refined our search terms. Given the focus on highly cited papers, these searches tended to identify older papers. The ‘recent literature’ search was designed to be more specifically focused on identifying emerging theories from different disciplines. It focused on subject-specific databases from the fields of health sciences (such as epidemiology, medical sociology, health economics, health psychology, health geography, clinical sciences, public health), economics, political sciences, geography, and sociology. This search was limited to papers published within the past 10 years to identify more recent theories and those that have current application.There are no well-tested search strategies for identifying theoretical literature. Our approach identified 5,021 papers; of these, 272 were employed in the review. Several of the authors had extensive collections of papers relevant to this study, referred to here as ‘personal collection’. To satisfy our curiosity of the final contribution of the electronic and hand searching to the income and health review, we compared original search results prior to de-duplication. For this exercise, we included personal collections and citation tracking as hand searching and the ‘highly cited’ and ‘recent literature’ electronic searches as electronic. The final proportions of these groups are shown in Figure 1 . Of the papers finally included in the income and health review, 76% were identified solely through hand searching: of these, 64% were in the personal collections of subject specialists and 12% came from either forward or backwards citation tracking. The citation searching included tracking references from papers found through the electronic searches. The electronic bibliographic searches identified 12% of final inclusion papers (along with a further 12% of included papers that were found both through the electronic and hand-searching methods). Therefore, for the income and health review, we found that electronic bibliographic literature searches had limitations, with a large amount of effort yielding a relatively small proportion of the final included papers. However, those papers were not identified by any of the other search strategies and hence were important to the aim of including multi-discipline literature. Citation tracking, both backwards and forwards, also resulted in useful literature being found, particularly for compiling our theoretical framework of how mechanisms interact to impact on health.

Source of included papers for the income and health review of theory.

Whilst piloting our electronic search strategy, we developed and tested search terms to help us identify theoretical papers. We found that the string of terms ‘theory or pathway or model or mechanism or review’ (with truncations appropriate to specific databases) were useful for identifying papers that discussed theories. Nonetheless, when the terms for ‘income’, ‘theory’, and ‘health’ were checked separately and then combined, we also found that 17% of papers that we wanted to retrieve from our initial (and intentionally broad) electronic search did not include all of the terms in the title or abstract—and therefore would have been missed from any literature search that used that term as a filter; 8% had no term to identify theory in the title or abstract.

In other reviews, the searching process for relevant theory has been dependent on the search strategy for empirical evidence on the same topic. The theory-based review by Baxter and Allmark on chest pain and medical assistance was conducted on literature identified from a previous systematic review of empirical evidence. Hence, the reviewers focused on literature already searched and filtered [ 12 ]. The review of theory on school environment and health combined searching for theory with the searches for relevant empirical studies [ 23 ]. Therefore, papers containing relevant theory were identified during the screening process of papers reporting empirical studies. A potential limitation of this approach is that it could omit publications that provided detailed theoretical discussions without presenting empirical data. Optimising the balance between search specificity and selectivity is a perennial problem for systematic reviewers. The challenges described here underline the need for multiple approaches, including formal electronic searches and hand searches, so that the strengths of one approach can help to compensate for the deficiencies of another whilst ensuring the reviewers’ task is manageable. A consequence of the initial broad electronic searching for the income and health review was the time it took to screen over 5,000 papers. This was amplified by the fact that frequently the title and abstract gave no indication of whether there was any theoretical content and the full text had to be retrieved and screened. This is likely to be a feature of many reviews of theory and perhaps consideration has to be given to the following: achieving a balance between including search terms to limit the focus to papers including theory, with the risk of missing important texts; acknowledging a realistic timescale required for thorough searching and screening for relevant papers, with the possibility of a low ‘hit’ rate; or reconsider the objectives to establish whether a tighter focus is preferable.

Data extraction

Reviewers have a number of options regarding how they select and extract data from included papers in such a way as to manage often substantial amounts of information and to aid synthesis. One option is to produce standardised extraction forms to help ensure that similar types of data are taken from each paper to facilitate cross-comparison. If the included documents are too heterogeneous to fit a standardised approach, or if the reviewers are looking to conduct more detailed qualitative analysis, an alternative approach is more useful. In systematic reviews of qualitative research, reviewers may work with whole texts rather than selected extracts, using ethnographic or other techniques to code and then analyse the data. Textual analysis software such as NVivo can be used to aid this process. If the reviewers feel they have a thorough knowledge of the papers, they may feel that formal data extraction and coding are unnecessary.

Reviewers of theory have a similar range of standardised and qualitative approaches to extracting data, and their choice may be determined on the purpose of the review (e.g. the extent of scoping or in-depth analysis) and their degree of familiarity with the material. As the income and health review combined an in-depth analysis of seminal literature with a broader scope of relevant theories, a combination of approaches was used. The analysis of the small number of key papers was conducted by subject specialists without a formal data extraction process. In contrast, the scoping part of the review led to the inclusion of 147 papers that were summarised using a data extraction form that we created in Microsoft Access specifically for the review (see Additional file 3 for fields included). The extracted data were then coded into broader categories of theory relating to causal mechanisms from the review of seminal papers. Data were extracted by one reviewer, and a second reviewer independently extracted a sample of studies; results were compared and differences discussed to develop a common consistent approach.

Quality appraisal

For most systematic reviews, appraisals of the methodological quality of included evidence are a crucial stage that then enables reviewers to determine the strength of evidence and potential for bias relating to specific findings. Within evidence synthesis, in particular qualitative synthesis, there is discussion of whether it is appropriate to appraise the quality of studies and what form such appraisals might take [ 4 , 24 ]. Similarly, theoretical evidence cannot be appraised using the kinds of tools which have been developed for more conventional systematic reviews, most of which tend to focus on internal validity and study design. Some reviews have emphasised theories identified in empirical papers that were judged to be of high methodological quality [ 12 ]. However, study methodology and theoretical development are different areas of research demanding different skills and so it does not necessarily follow that high quality empirical methods necessarily occur alongside good or influential theories [ 24 ]. It may be that the appraisal process helps to distinguish between papers presenting a theory based on flawed empirical study and papers presenting a comprehensively argued theory which fail to clearly report research methods.

Detailed appraisal of theories is likely to involve an inductive and subjective approach by researchers with a thorough knowledge of the field, rather than the use of standardised checklists (although one exception to this is the checklist devised by Bonell et al. [ 23 ]). Our income and health review did not include a standardised critical appraisal of the theories we included. In retrospect, it may have been useful to have attempted to grade theories by relevance to the review question and, possibly, by level of detail or originality, to help exclude studies that included relatively minor theoretical discussions or simply referred to the work of other theorists.

Approaches to data synthesis will differ depending on the different aims of a review. Gough helpfully distinguishes between aggregative and configurative reviews—the former generally focus on synthesising empirical papers and ‘add up’ their findings, whilst the latter aim to interpret and configure findings from existing literature to develop new understandings of existing research [ 4 ]. Theoretical reviews often lean more to configurative approaches but may also contain some aspects of aggregation depending on the aim. This results in different approaches to synthesis. Some reviews (e.g. Bonell et al. [ 11 ]) have treated the individual theory as the unit of analysis, with a focus on constructing a typology of theories within an overarching picture of causal determinants. Others have an in-depth or configurative approach, for example, Lorenc et al. [ 25 ] aimed to analytically isolate specific causal or interpretive assertions from diverse theories and then to develop a causal ‘map’ of the interrelations between different factors.

However, there remain a number of unanswered questions around synthesis of theories, particularly whether diverse, complex, and potentially incommensurable conceptual vocabularies can be effectively integrated. A review of theory that attempted a more in-depth analysis could incorporate techniques developed for qualitative reviews, for example, from thematic synthesis [ 26 ] or meta-ethnography [ 27 ]. The reviewers could attempt to distinguish between different orders of theory: those framed directly around specific data, those that result from an author’s attempts to juxtapose pre-existing theories and/or ideological positions with empirical observations, and those resulting from the reviewers own reflections based on comparisons of the included literature. Broadly following the meta-ethnographical approach, reviewers could explore whether the relationship between different theories is reciprocal (i.e. the theories are mutually supportive) or refutational (i.e. the theories appear to contradict one another) or whether the theories can potentially form part of the same line of argument (e.g. by representing different stages along the same causal pathway) [ 27 ].

As has been noted, the income and health review was a hybrid that combined an expert review of key literature with a wider scope of relevant theoretical literature drawn from systematic searches. The seminal texts in the expert review were synthesised through a subjective process of induction by specialists who had immersed themselves in the literature. A key synthesising stage of the systematic searches was the interpretative collating of findings which was used to create a causal map and review the key concepts and relations that were believed to be important. Through an iterative process of checking between this mapping process and the themes we had developed from the systematic scoping literature, a framework of theoretical pathways between income and health was constructed.

The synthesis process used in the income and health review combined standardised and iterative elements. Guided by Baxter et al.’s [ 6 ] method of developing a conceptual framework, papers were scanned to extract descriptions of specific pathways/theories linking income to health. The extracted literature was organised by a coding framework: a typology of theories, developed iteratively in conjunction with the analysis of seminal texts. The extracted texts were then organised by themes emerging from the data within each theory type, drawing together similar theoretical pathways from differing disciplines including sociology, economics, public health, and psychology. Narrative synthesis techniques were used to scope, compare, and contrast the key theories that were identified and focused on: the definition of key concepts, hypothesised pathways, the range of contextual factors included in the model/theory, and the time sequencing of hypothesised influences and outcomes within the lifecourse. These methods are similar to the processes involved in thematic synthesis described by Thomas and Harden [ 26 ]. In retrospect, awareness that the synthesis process we undertook would concentrate entirely on qualitative techniques would have enabled us to adopt qualitative software and analysis methods at an early stage of the review. This may have made the data collection quicker and the synthesis more intuitive.

In this article, we have discussed some of the methodological issues involved when conducting a review of theory, using examples from a recently conducted theoretical review of income and health. The article should be read as a discussion of what we learnt rather than an attempt at formal guidance. The aim has been to help provide a starting point for anyone considering their own review of theory to think about the possible purpose of their review and the methods that are most appropriate for that purpose. We suggest that there are a spectra of methods for conducting theory reviews that stretch from scoping out theories relating to a particular issue to in-depth analysis of key theoretical works with the aim of developing new, overarching theories and interpretations. The two types of approach are not mutually exclusive; the income and health review included elements of both. We think it may be useful at the outset of a review of theory to spend time considering whether the key aim of the review is to scope, to conduct in-depth analysis, or to combine both these aspects in the review. Identifying the type of review can clarify the most appropriate approach. Scoping reviews are more likely to require a more standardised approach to searching, inclusion and exclusion, and data extraction to help manage the potentially large numbers of studies that may be identified. However, in our experience, scoping reviews of theory also benefit from the flexibility and nuance that can come from more subjective and inductive processes. In-depth reviews of theory are likely to involve iterations and inductive processes throughout, and we have suggested that some of the concepts and techniques that have been developed for qualitative evidence synthesis can be usefully translated to theory reviews of this kind.

Reflecting on our experience of conducting the review of theories on income and health, we feel that there were positive and negative aspects to the process. Table 1 summarises the main challenges we faced. Taking the time to grapple with defining and applying inclusion criteria was a process which helped clarify what we were looking for and how we wanted to use it. The systematic searching was extensive and laborious, and we found that it contributed only a small amount to the review in comparison with that found through personal libraries. However, those papers would have been omitted without the systematic search methods, probably reducing the scope of the review.

Our team of authors included members with substantial knowledge of the income and health topic; it is possible that conducting the review without access to this knowledge would make the systematic searching of far greater relevance. The team also included members with considerable experience in conducting systematic reviews. Although this had some advantages in terms of methodological expertise, we have tried to show here that systematic review methods are not always appropriate or may need to be adapted for theory reviews—and the reviewers need the confidence and flexibility to do this.

We suggested in the background above that systematic methods may be valuable in reviews of theory for two reasons: to complement the review team’s existing expertise as a framework for hypothesis generation and to increase reliability in the synthesis. Our experience suggests that these benefits are real, in that the systematic approach helps to distance reviewers from commitments to particular perspectives. Nonetheless, reviewer expertise continued to define the interpretation of the theories and was also indispensable in searching.

Reviewers wondering which approach and methods would best suit them should consider the purpose of the review in terms of what would be most useful to end users. Furthermore, if reviews of theory are to be more common, their general utility requires greater consideration. At this stage in their development, there is an opportunity to pose searching questions about the uses and usefulness of such reviews. How would the focus and content alter depending on whether their main function was as an academic resource, as a support for decision makers, or as a combination of the two? Do their findings genuinely advance our understanding of theory (e.g. by identifying overlooked theories, by showing how apparently rival theories relate to one another, or by aiding the generation of meta-theories)? Conversely, do they tend to reiterate theoretical viewpoints that are already well established (including, for example, the view that social phenomena are frequently ‘complex’)? Future work on this kind of synthesis will doubtless lead to a refinement of methods and can shed more light on the added value that can be obtained by reviewing theory.

Gorelick R: What is theory?. Ideas EcolEvol. 2011, 4: 1-10.

Google Scholar

Popper K: The Logic of Scientific Discovery. 1959, London: Routledge

Merton RK: Social Theory and Social Structure. 1968, New York: Free Press

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S: Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev. 2012, 1: 28-10.1186/2046-4053-1-28.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Neary D, Clayton S, Wright K, Thomson H, Cummins S, Sowden A, Renton A: Crime, fear of crime and mental health: synthesis of theory and systematic reviews of interventions and qualitative evidence. Public Health Res. 2013, 13: 496-

Baxter S, Killoran A, Kelly MP, Goyder E: Synthesizing diverse evidence: the use of primary qualitative data analysis methods and logic models in public health reviews. Public Health. 2010, 124: 99-106. 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.01.002.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Tugwell P, Petticrew M, Kristjansson E, Welch V, Ueffing E, Waters E, Bonnefoy J, Morgan A, Doohan E, Kelly MP: Assessing equity in systematic reviews: realising the recommendations of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. BMJ. 2010, 341: c4739-10.1136/bmj.c4739.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Anderson LM, Petticrew M, Rehfuess E, Armstrong R, Ueffing E, Baker P, Francis D, Tugwell P: Using logic models to capture complexity in systematic reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2011, 2: 33-42. 10.1002/jrsm.32.

Lorenc T, Pearson M, Jamal F, Cooper C, Garside R: The role of systematic reviews of qualitative evidence in evaluating interventions: a case study. Res Synth Methods. 2012, 3: 1-10. 10.1002/jrsm.1036.

Benzeval M, Bond L, Campbell M, Egan M, Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Popham F: How does Money Influence Health?. 2014, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Bonell CP, Fletcher A, Jamal F, Wells H, Harden A, Murphy S, Thomas J: Theories of how the school environment impacts on student health: systematic review and synthesis. Health Place. 2013, 24: 242-249.

Baxter S, Allmark P: Reducing the time-lag between onset of chest pain and seeking professional medical help: a theory-based review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013, 13: 15-10.1186/1471-2288-13-15.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K: Realist synthesis: an Introduction. 2004, ESRC Research Methods Programme Manchester: University of Manchester

Pearson M, Chilton R, Woods HB, Wyatt K, Ford T, Abraham C, Anderson R: Implementing health promotion in schools: protocol for a realist systematic review of research and experience in the United Kingdom (UK). Syst Rev. 2012, 1: 48-10.1186/2046-4053-1-48.

Petticrew M, Roberts H: Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A Practical Guide. 2006, Oxford: Blackwell

Book Google Scholar

Hill B, Skouteris H, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M: Interventions designed to limit gestational weight gain: a systematic review of theory and meta-analysis of intervention components. Obes Rev. 2013, 14 (6): 435-450. 10.1111/obr.12022.

Sherman KA, Kasparian NA, Mireskandari S: Psychological adjustment among male partners in response to women’s breast/ovarian cancer risk: a theoretical review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology. 2010, 19: 1-11. 10.1002/pon.1582.

Bambra C: Real world reviews: a beginner’s guide to undertaking systematic reviews of public health policy interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011, 65: 14-19. 10.1136/jech.2009.088740.

Hannes K: Critical appraisal of qualitative research. Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Edited by: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, Harris J, Lewin S, Lockwood C. 2011, The Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group, http://cqim.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance ,

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A: Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012, 22: 1435-1443. 10.1177/1049732312452938.

Department of Health and Social Security: Inequalities in Health: Report of a Working Group, Chaired by Sir Douglas Black. 1980, London: DHSS

Pawson R, Tilley N: Realistic Evaluation. 1997, London: Sage Publications Ltd

Bonell C, Jamal F, Harden A, Wells H, Parry W, Fletcher A, Petticrew M, Thomas J, Whitehead M, Campbell R, Murphy S, Moore L: Systematic review of the effects of schools and school environment interventions on health: evidence mapping and synthesis. Public Health Res. 2013, 1: doi:10.3310/phr01010

Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M, Daker-White G, Britten N, Pill R, Yardley L, Pope C, Donovan J: Evaluating meta-ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technol Assess. 2011, 15: 43-

Article Google Scholar

Lorenc T, Clayton S, Neary D, Whitehead M, Petticrew M, Thomson H, Cummins S, Sowden A, Renton A: Crime, fear of crime, environment, and mental health and wellbeing: mapping review of theories and causal pathways. Health Place. 2012, 18: 757-765. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.001.

Thomas J, Harden A: Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008, 8: 45-10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Noblit GW, Hare RD: Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. 1988, London: Sage Publications Inc

Whitehead M:The health divide. Inequalities in Health: the Black Report and the Health Divide. edn. Edited by: Townsend P, Whitehead M, Davidson N. 1992, London: Penguin, 213-

Macintyre S: The Black Report and beyond: what are the issues?. Soc Sci Med. 1997, 44 (6): 723-745. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00183-9.

Adler NE, Stewart J: Health disparities across the lifespan: meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010, 1186: 5-23. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05337.x.

Kroenke C: Socioeconomic status and health: youth development and neomaterialist and psychosocial mechanisms. Soc Sci Med. 2008, 66: 31-42. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.018.

Friedman EM, Love GD, Rosenkranz MA, Urry HL, Davidson RJ, Singer BH, Ryff CD: Socioeconomic status predicts objective and subjective sleep quality in aging women. Psychosom Med. 2007, 69: 682-691. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31814ceada.

Klabbers G, Bosma H, Van Lenthe FJ, Kempen GI, Van Eijk JT, Mackenbach JP: The relative contributions of hostility and depressive symptoms to the income gradient in hospital-based incidence of ischaemic heart disease: 12-year follow-up findings from the GLOBE study. Soc Sci Med. 2009, 69: 1272-1280. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.031.

McLoyd VC: The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Dev. 1990, 61: 311-346. 10.2307/1131096.

Huston AC, McLoyd VC, Coll CG: Children and poverty: issues in contemporary research. Child Dev. 1994, 65: 275-282. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00750.x.

Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC: Stress, health, and the life course: some conceptual perspectives. J Health Soc Behav. 2005, 46: 205-219. 10.1177/002214650504600206.

Theodossiou I, Zangelidis A: The social gradient in health: the effect of absolute income and subjective social status assessment on the individual’s health in Europe. Econ Hum Biol. 2009, 7: 229-237. 10.1016/j.ehb.2009.05.001.

Jeffery RW, French SA: Socioeconomic status and weight control practices among 20- to 45-year-old women. Am J Public Health. 1996, 86: 1005-1010. 10.2105/AJPH.86.7.1005.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pampel FC, Krueger PM, Denney JT: Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010, 36: 349-370. 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102529.

Raphael D, Macdonald J, Colman R, Labonte R, Hayward K, Torgerson R: Researching income and income distribution as determinants of health in Canada: gaps between theoretical knowledge, research practice, and policy implementation. Health Policy. 2005, 72: 217-232. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.08.001.

Cerdá M, Johnson-Lawrence VD, Galea S: Lifetime income patterns and alcohol consumption: investigating the association between long- and short-term income trajectories and drinking. Soc Sci Med. 2011, 73: 1178-1185. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.025.

Download references

Acknowledgements

MC was funded on the income and health review of theory by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. At the time of the review, LB, ME and CF were funded by the UK Medical Research Council/Chief Scientist Office Evaluating the Health Effects of Social Interventions programme (MC_UU_12017/4), and MC is currently funded by this programme; MB and FP were funded by the Social Patterning of Health over the Lifecourse programme (MC_UU_12017/7) at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow. Mark Petticrew, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, was a co-author of the income and health review of theory and provided helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

Mhairi Campbell, Frank Popham, Candida Fenton & Michaela Benzeval

NHS NIHR School of Public Health Research, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK

STEaPP, University College London, London, UK

Theo Lorenc

Centre of Excellence in Intervention and Prevention Science, Melbourne, Australia

Lyndal Bond

Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex, Colchester, UK

Michaela Benzeval

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mhairi Campbell .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MC and ME wrote the first draft of this article, with MB and TL contributing to drafting. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript and approved the final draft. All authors were involved in developing and conducting the income health review of theory.

Electronic supplementary material

13643_2014_288_moesm1_esm.doc.

Additional file 1: Purpose and methods for the income and health review [ [ 21 ] , [ 28 ] - [ 30 ] ]. The review is on theories about causal relationships between income and health. (DOC 48 KB)

13643_2014_288_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional file 2: Further details of income and health electronic literature searches. Details show development of a two part electronic search strategy. (DOC 48 KB)

13643_2014_288_MOESM3_ESM.doc

Additional file 3: Data extraction for the income and health review [ [ 30 ] - [ 41 ] ]. List shows the details collected from the papers included in the systematic search. (DOC 48 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Campbell, M., Egan, M., Lorenc, T. et al. Considering methodological options for reviews of theory: illustrated by a review of theories linking income and health. Syst Rev 3 , 114 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-114

Download citation

Received : 22 May 2014

Accepted : 24 September 2014

Published : 13 October 2014

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-114

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Systematic review

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Literature Review: Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Review

- Purpose of a Literature Review

- Work in Progress

- Compiling & Writing

- Books, Articles, & Web Pages

Types of Literature Reviews

- Departmental Differences

- Citation Styles & Plagiarism

- Know the Difference! Systematic Review vs. Literature Review

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers.

- First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish.

- Second, are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies.

- Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinions, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomenon. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

- << Previous: Books, Articles, & Web Pages

- Next: Departmental Differences >>

- Last Updated: Oct 19, 2023 12:07 PM

- URL: https://uscupstate.libguides.com/Literature_Review

Which review is that? A guide to review types.

- Which review is that?

- Review Comparison Chart

- Decision Tool

- Critical Review

- Integrative Review

- Narrative Review

- State of the Art Review

- Narrative Summary

- Systematic Review

- Meta-analysis

- Comparative Effectiveness Review

- Diagnostic Systematic Review

- Network Meta-analysis

- Prognostic Review

- Psychometric Review

- Review of Economic Evaluations

- Systematic Review of Epidemiology Studies

- Living Systematic Reviews

- Umbrella Review

- Review of Reviews

- Rapid Review

- Rapid Evidence Assessment

- Rapid Realist Review

- Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

- Qualitative Interpretive Meta-synthesis

- Qualitative Meta-synthesis

- Qualitative Research Synthesis

- Framework Synthesis - Best-fit Framework Synthesis

- Meta-aggregation

- Meta-ethnography

- Meta-interpretation

- Meta-narrative Review

- Meta-summary

- Thematic Synthesis

- Mixed Methods Synthesis

- Narrative Synthesis

- Bayesian Meta-analysis

- EPPI-Centre Review

- Critical Interpretive Synthesis

- Realist Synthesis - Realist Review

- Scoping Review

- Mapping Review

- Systematised Review

- Concept Synthesis

- Expert Opinion - Policy Review

- Technology Assessment Review

Methodological Review

- Systematic Search and Review

A methodological review is a type of systematic secondary research (i.e., research synthesis) which focuses on summarising the state-of-the-art methodological practices of research in a substantive field or topic" (Chong et al, 2021).

Methodological reviews "can be performed to examine any methodological issues relating to the design, conduct and review of research studies and also evidence syntheses". Munn et al, 2018)

Further Reading/Resources

Clarke, M., Oxman, A. D., Paulsen, E., Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (2011). Appendix A: Guide to the contents of a Cochrane Methodology protocol and review. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions . Full Text PDF

Aguinis, H., Ramani, R. S., & Alabduljader, N. (2023). Best-Practice Recommendations for Producers, Evaluators, and Users of Methodological Literature Reviews. Organizational Research Methods, 26(1), 46-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120943281 Full Text

Jha, C. K., & Kolekar, M. H. (2021). Electrocardiogram data compression techniques for cardiac healthcare systems: A methodological review. IRBM . Full Text

References Munn, Z., Stern, C., Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., & Jordan, Z. (2018). What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC medical research methodology , 18 (1), 1-9. Full Text Chong, S. W., & Reinders, H. (2021). A methodological review of qualitative research syntheses in CALL: The state-of-the-art. System , 103 , 102646. Full Text

- << Previous: Technology Assessment Review

- Next: Systematic Search and Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 30, 2024 9:02 AM

- URL: https://unimelb.libguides.com/whichreview

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.