Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Drama Criticism › Analysis of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House

Analysis of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 27, 2020 • ( 0 )

Whether one reads A Doll’s House as a technical revolution in modern theater, the modern tragedy, the first feminist play since the Greeks, a Hegelian allegory of the spirit’s historical evolution, or a Kierkegaardian leap from aesthetic into ethical life, the deep structure of the play as a modern myth of self-transformation ensures it perennial importance as a work that honors the vitality of the human spirit in women and men.

—Errol Durbach, A Doll’s House : Ibsen’s Myth of Transformation

More than one literary historian has identified the precise moment when modern drama began: December 4, 1879, with the publication of Ibsen ’s Etdukkehjem ( A Doll’s House ), or, more dramatically at the explosive climax of the first performance in Copenhagen on December 21, 1879, with the slamming of the door as Nora Helmer shockingly leaves her comfortable home, respectable marriage, husband, and children for an uncertain future of self-discovery. Nora’s shattering exit ushered in a new dramatic era, legitimizing the exploration of key social problems as a serious concern for the modern theater, while sounding the opening blast in the modern sexual revolution. As Henrik Ibsen ’s biographer Michael Meyer has observed, “No play had ever before contributed so momentously to the social debate, or been so widely and furiously discussed among people who were not normally interested in theatrical or even artistic matter.” A contemporary reviewer of the play also declared: “When Nora slammed the door shut on her marriage, walls shook in a thousand homes.”

Ibsen set in motion a transformation of drama as distinctive in the history of the theater as the one that occurred in fifth-century b.c. Athens or Elizabethan London. Like the great Athenian dramatists and William Shakespeare, Ibsen fundamentally redefined drama and set a standard that later playwrights have had to absorb or challenge. The stage that he inherited had largely ceased to function as a serious medium for the deepest consideration of human themes and values. After Ibsen drama was restored as an important truth-telling vehicle for a comprehensive criticism of life. A Doll’s House anatomized on stage for the first time the social, psychological, emotional, and moral truths beneath the placid surface of a conventional, respectable marriage while creating a new, psychologically complex modern heroine, who still manages to shock and unsettle audiences more than a century later. A Doll’s House is, therefore, one of the ground-breaking modern literary texts that established in fundamental ways the responsibility and cost of women’s liberation and gender equality. According to critic Evert Sprinchorn, Nora is “the richest, most complex” female dramatic character since Shakespeare’s heroines, and as feminist critic Kate Millett has argued in Sexual Politics, Ibsen was the first dramatist since the Greeks to challenge the myth of male dominance. “In Aeschylus’ dramatization of the myth,” Millett asserts, “one is permitted to see patriarchy confront matriarchy, confound it through the knowledge of paternity, and come off triumphant. Until Ibsen’s Nora slammed the door announcing the sexual revolution, this triumph went nearly uncontested.”

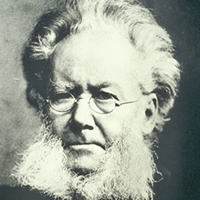

The momentum that propelled Ibsen’s daring artistic and social revolt was sustained principally by his outsider status, as an exile both at home and abroad. His last deathbed word was “ Tvertimod !” (On the contrary!), a fitting epitaph and description of his artistic and intellectual mindset. Born in Skien, Norway, a logging town southwest of Oslo, Ibsen endured a lonely and impoverished childhood, particularly after the bankruptcy of his businessman father when Ibsen was eight. At 15, he was sent to Grimstad as an apothecary’s apprentice, where he lived for six years in an attic room on meager pay, sustained by reading romantic poetry, sagas, and folk ballads. He later recalled feeling “on a war footing with the little community where I felt I was being suppressed by my situation and by circumstances in general.” His first play, Cataline , was a historical drama featuring a revolutionary hero who reflects Ibsen’s own alienation. “ Cataline was written,” the playwright later recalled, “in a little provincial town, where it was impossible for me to give expression to all that fermented in me except by mad, riotous pranks, which brought down upon me the ill will of all the respectable citizens who could not enter into that world which I was wrestling with alone.”

Largely self-educated, Ibsen failed the university entrance examination to pursue medical training and instead pursued a career in the theater. In 1851 he began a 13-year stage apprenticeship in Bergen and Oslo, doing everything from sweeping the stage to directing, stage managing, and writing mostly verse dramas based on Norwegian legends and historical subjects. The experience gave him a solid knowledge of the stage conventions of the day, particularly of the so-called well-made play of the popular French playwright Augustin Eugène Scribe and his many imitators, with its emphasis on a complicated, artificial plot based on secrets, suspense, and surprises. Ibsen would transform the conventions of the well-made play into the modern problem play, exploring controversial social and human questions that had never before been dramatized. Although his stage experience in Norway was marked chiefly by failure, Ibsen’s apprenticeship was a crucial testing ground for perfecting his craft and providing him with the skills to mount the assault on theatrical conventions and moral complacency in his mature work.

In 1864 Ibsen began a self-imposed exile from Norway that would last 27 years. He traveled first to Italy, where he was joined by his wife, Susannah, whom he had married in 1858, and his son. The family divided its time between Italy and Germany. The experience was liberating for Ibsen; he felt that he had “escaped from darkness into light,” releasing the productive energy with which he composed the succession of plays that brought him worldwide fame. His first important works, Brand (1866) and Peer Gynt (1867), were poetic dramas, very much in the romantic mode of the individual’s conflict with experience and the gap between heroic assertion and accomplishment, between sobering reality and blind idealism. Pillars of Society (1877) shows him experimenting with ways of introducing these central themes into a play reflecting modern life, the first in a series of realistic dramas that redefined the conventions and subjects of the modern theater.

The first inklings of his next play, A Doll’s House , are glimpsed in Ibsen’s journal under the heading “Notes for a Modern Tragedy”:

There are two kinds of moral laws, two kinds of conscience, one for men and one, quite different, for women. They don’t understand each other; but in practical life, woman is judged by masculine law, as though she weren’t a woman but a man.

The wife in the play ends by having no idea what is right and what is wrong; natural feelings on the one hand and belief in authority on the other lead her to utter distraction. . . .

Moral conflict. Weighed down and confused by her trust in authority, she loses faith in her own morality, and in her fitness to bring up her children. Bitterness. A mother in modern society, like certain insects, retires and dies once she has done her duty by propagating the race. Love of life, of home, of husband and children and family. Now and then, as women do, she shrugs off her thoughts. Suddenly anguish and fear return. Everything must be borne alone. The catastrophe approaches, mercilessly, inevitably. Despair, conflict, and defeat.

To tell his modern tragedy based on gender relations, Ibsen takes his audience on an unprecedented, intimate tour of a contemporary, respectable marriage. Set during the Christmas holidays, A Doll’s House begins with Nora Helmer completing the finishing touches on the family’s celebrations. Her husband, Torvald, has recently been named a bank manager, promising an end to the family’s former straitened financial circumstances, and Nora is determined to celebrate the holiday with her husband and three children in style. Despite Torvald’s disapproval of her indulgences, he relents, giving her the money she desires, softened by Nora’s childish play-acting, which gratifies his sense of what is expected of his “lark” and “squirrel.” Beneath the surface of this apparently charming domestic scene is a potentially damning and destructive secret. Seven years before Nora had saved the life of her critically ill husband by secretly borrowing the money needed for a rest cure in Italy. Knowing that Torvald would be too proud to borrow money himself, Nora forged her dying father’s name on the loan she received from Krogstad, a banking associate of Torvald.

The crisis comes when Nora’s old schoolfriend Christina Linde arrives in need of a job. At Nora’s urging Torvald aids her friend by giving her Krogstad’s position at the bank. Learning that he is to be dismissed, Krogstad threatens to expose Nora’s forgery unless she is able to persuade Torvald to reinstate him. Nora fails to convince Torvald to relent, and after receiving his dismissal notice, Krogstad sends Torvald a letter disclosing the details of the forgery. The incriminating letter remains in the Helmers’ mailbox like a ticking time-bomb as Nora tries to distract Torvald from reading it and Christina attempts to convince Krogstad to withdraw his accusation. Torvald eventu-ally reads the letter following the couple’s return from a Christmas ball and explodes in recriminations against his wife, calling her a liar and a criminal, unfit to be his wife and his children’s mother. “Now you’ve wrecked all my happiness—ruined my whole future,” Torvald insists. “Oh, it’s awful to think of. I’m in a cheap little grafter’s hands; he can do anything he wants with me, ask me for anything, play with me like a puppet—and I can’t breathe a word. I’ll be swept down miserably into the depths on account of a featherbrained woman.” Torvald’s reaction reveals that his formerly expressed high moral rectitude is hypocritical and self-serving. He shows himself worried more about appearances than true morality, caring about his reputation rather than his wife. However, when Krogstad’s second letter arrives in which he announces his intention of pursuing the matter no further, Torvald joyfully informs Nora that he is “saved” and that Nora should forget all that he has said, assuming that the normal relation between himself and his “frightened little songbird” can be resumed. Nora, however, shocks Torvald with her reaction.

Nora, profoundly disillusioned by Torvald’s response to Krogstad’s letter, a response bereft of the sympathy and heroic self-sacrifice she had hoped for, orders Torvald to sit down for a serious talk, the first in their married life, in which she reviews their relationship. “I’ve been your doll-wife here, just as at home I was Papa’s doll-child,” Nora explains. “And in turn the children have been my dolls. I thought it was fun when you played with me, just as they thought it fun when I played with them. That’s been our marriage, Torvald.” Nora has acted out the 19th-century ideal of the submissive, unthinking, dutiful daughter and wife, and it has taken Torvald’s reaction to shatter the illusion and to force an illumination. Nora explains:

When the big fright was over—and it wasn’t from any threat against me, only for what might damage you—when all the danger was past, for you it was just as if nothing had happened. I was exactly the same, your little lark, your doll, that you’d have to handle with double care now that I’d turned out so brittle and frail. Torvald—in that instant it dawned on me that I’ve been living here with a stranger.

Nora tells Torvald that she no longer loves him because he is not the man she thought he was, that he was incapable of heroic action on her behalf. When Torvald insists that “no man would sacrifice his honor for love,” Nora replies: “Millions of women have done just that.”

Nora finally resists the claims Torvald mounts in response that she must honor her duties as a wife and mother, stating,

I don’t believe in that anymore. I believe that, before all else, I’m a human being, no less than you—or anyway, I ought to try to become one. I know the majority thinks you’re right, Torvald, and plenty of books agree with you, too. But I can’t go on believing what the majority says, or what’s written in books. I have to think over these things myself and try to understand them.

The finality of Nora’s decision to forgo her assigned role as wife and mother for the authenticity of selfhood is marked by the sound of the door slamming and her exit into the wider world, leaving Torvald to survey the wreckage of their marriage.

Ibsen leaves his audience and readers to consider sobering truths: that married women are the decorative playthings and servants of their husbands who require their submissiveness, that a man’s authority in the home should not go unchallenged, and that the prime duty of anyone is to arrive at an authentic human identity, not to accept the role determined by social conventions. That Nora would be willing to sacrifice everything, even her children, to become her own person proved to be, and remains, the controversial shock of A Doll’s House , provoking continuing debate over Nora’s motivations and justifications. The first edition of 8,000 copies of the play quickly sold out, and the play was so heatedly debated in Scandinavia in 1879 that, as critic Frances Lord observes, “many a social invitation in Stockholm during that winter bore the words, ‘You are requested not to mention Ibsen’s Doll’s House!” Ibsen was obliged to supply an alternative ending for the first German production when the famous leading lady Hedwig Niemann-Raabe refused to perform the role of Nora, stating that “I would never leave my children !” Ibsen provided what he would call a “barbaric outrage,” an ending in which Nora’s departure is halted at the doorway of her children’s bedroom. The play served as a catalyst for an ongoing debate over feminism and women’s rights. In 1898 Ibsen was honored by the Norwegian Society for Women’s Rights and toasted as the “creator of Nora.” Always the contrarian, Ibsen rejected the notion that A Doll’s House champions the cause of women’s rights:

I have been more of a poet and less of a social philosopher than people generally tend to suppose. I thank you for your toast, but must disclaim the honor of having consciously worked for women’s rights. I am not even quite sure what women’s rights really are. To me it has been a question of human rights. And if you read my books carefully you will realize that. Of course it is incidentally desirable to solve the problem of women; but that has not been my whole object. My task has been the portrayal of human beings.

Despite Ibsen’s disclaimer that A Doll’s House should be appreciated as more than a piece of gender propaganda, that it deals with universal truths of human identity, it is nevertheless the case that Ibsen’s drama is one of the milestones of the sexual revolution, sounding themes and advancing the cause of women’s autonomy and liberation that echoes Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and anticipates subsequent works such as Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique.

A Doll’s House Ebook PDF (1 MB)

Analysis of Henrik Ibsen’s Plays

Share this:

Categories: Drama Criticism , Literature

Tags: A Doll's House Analysis , A Doll's House Feminism , A Doll's House Guide , A Doll's House Summary , A Doll's House Themes , A Doll’s House , A Doll’s House Critcal Studies , A Doll’s House Criticism , A Doll’s House Essay , A Doll’s House Feminist Reading , A Doll’s House Lecture , A Doll’s House PDF , Analysis Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Bibliography Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Character Study Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Criticism Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Drama Criticism , Essays Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Feminism , Henrik Ibsen , Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Literary Criticism , Notes Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Plot Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Simple Analysis Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Study Guides Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Summary Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Synopsis Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House , Themes Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

A Summary and Analysis of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

A Doll’s House is one of the most important plays in all modern drama. Written by the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen in 1879, the play is well-known for its shocking ending, which attracted both criticism and admiration from audiences when it premiered.

Before we offer an analysis of A Doll’s House , it might be worth recapping the ‘story’ of the play, which had its roots in real-life events involving a friend of Ibsen’s.

A Doll’s House : summary

The play opens on Christmas Eve. Nora Helmer has returned home from doing the Christmas shopping. Her husband, a bank manager named Torvald, asks her how much she has spent. Nora confides to her friend Mrs Linde that, shortly after she and Torvald married, he fell ill and she secretly borrowed some money to pay for his treatment. Mrs Linde is looking for work from Nora’s husband.

She is still paying that money back (by setting aside a little from her housekeeping money on a regular basis) to the man she borrowed it from, Krogstad – a man who, it just so happens, works for Nora’s husband … who is about to sack Krogstad for forging another person’s signature.

But Krogstad knows Nora’s secret, that she forged her father’s signature, and he tells her in no uncertain terms that, if she lets her husband sack him, Krogstad will make sure her husband knows her secret.

But Torvald refuses to grant Nora’s request when she beseeches him to go easy on Krogstad and give him another chance. It looks as though all is over for Nora and her husband will soon know what she did.

The next day – Christmas Day – Nora is waiting for the letter from Krogstad to arrive, and for her secret to be revealed. She entreats her husband to be lenient towards Krogstad, but again, Torvald refuses, sending the maid off with the letter for Krogstad which informs him that he has been dismissed from Torvald’s employment.

Doctor Rank, who is dying of an incurable disease, arrives as Nora is getting ready for a fancy-dress party. Nora asks him if he will help her, and he vows to do so, but before she can say any more, Krogstad appears with his letter for Torvald. Now he’s been sacked, he is clearly going to go through with his threat and tell his former employer the truth about what Helmer’s wife did.

When Mrs Linde – who was romantically involved with Krogstad – arrives, she tries to appeal to Krogstad’s better nature, but he refuses to withdraw the letter. Then Torvald arrives, and Nora dances for him to delay her husband from reading Krogstad’s letter.

The next act takes place the following day: Boxing Day. The Helmers are at their fancy-dress party. Meanwhile, we learn that Mrs Linde broke it off with Krogstad because he had no money, and she needed cash to pay for her mother’s medical treatment. Torvald has offered Mrs Linde Krogstad’s old job, but she says that she really wants him – money or no money – and the two of them are reconciled.

When Nora returns with Torvald from the party, Mrs Linde, who had prevented Krogstad from having a change of heart and retrieving his letter, tells Nora that she should tell her husband everything. Nora refuses, and Torvald reads the letter from Krogstad anyway.

Nora is distraught, and sure enough, Torvald blames her – until another letter from Krogstad arrives, cancelling Nora’s debt to him, whereupon Torvald forgives her completely.

But Nora has realised something about her marriage to Torvald, and, changing out of her fancy-dress outfit, she announces that she is leaving him. She takes his ring and gives him hers, before going to the door and leaving her husband – slamming the door behind her.

A Doll’s House : analysis

A Doll’s House is one of the most important plays in all of modern theatre. It arguably represents the beginning of modern theatre itself. First performed in 1879, it was a watershed moment in naturalist drama, especially thanks to its dramatic final scene. In what has become probably the most famous statement made about the play, James Huneker observed: ‘That slammed door reverberated across the roof of the world.’

Why? It’s not hard to see why, in fact. And the answer lies in the conventional domestic scenarios that were often the subject of European plays of the period when Ibsen was writing. Indeed, these scenarios are well-known to anyone who’s read Ibsen’s play, because A Doll’s House is itself a classic example of this kind of conventional play.

Yes: the shocking power of Ibsen’s play lies not in the main part of the play itself but in its very final scene, which undoes and subverts everything that has gone before.

This conventional play, the plot of which A Doll’s House follows with consummate skill on Ibsen’s part, is a French tradition known as the ‘ well-made play ’.

Well-made plays have a tight plot, and usually begin with a secret kept from one or more characters in the play (regarding A Doll’s House : check), a back-story which is gradually revealed during the course of the play (check), and a dramatic resolution, which might either involve reconciliation when the secret is revealed, or, in the case of tragedies, the death of one or more of the characters.

Ibsen flirts with both kinds of endings, the comic and the tragic, at the end of A Doll’s House : when Nora knows her secret’s out, she contemplates taking her own life. But when Torvald forgives her following the arrival of Krogstad’s second letter, it looks as though a tragic ending has been averted and we have a comic one in its place.

Just as the plot of the play largely follows these conventions, so Ibsen is careful to portray both Torvald Helmer and his wife Nora as a conventional middle-class married couple. Nora’s behaviour at the end of the play signals an awakening within her, but this is all the more momentous, and surprising, because she is hardly what we would now call a radical feminist.

Similarly, her husband is not nasty to her: he doesn’t mistreat her, or beat her, or put her down, even if he patronises her as his ‘doll’ or ‘bird’ and encourages her to behave like a silly little creature for him. But Nora encourages him to carry on doing so.

They are both caught up in bourgeois ideology: financial security is paramount (as symbolised by Torvald’s job at the bank); the wife is there to give birth to her husband’s children and to dote on him a little, dancing for him and indulging in his occasional whims.

A Doll’s House takes such a powerful torch to all this because it lights a small match underneath it, not because it douses everything in petrol and sets off a firebomb.

And it’s worth noting that, whilst Ibsen was a champion of women’s rights and saw them as their husbands’ intellectual equal, A Doll’s House does not tell us whether we should support or condemn Nora’s decision to walk out on her husband. She has, after all, left her three blameless children without a mother, at least until she returns – if she ever does return. Is she selfish?

Of course, that is something that the play doesn’t answer for us. Ibsen himself later said that he was not ‘tendentious’ in anything he wrote: like a good dramatist, he explores themes which perhaps audiences and readers hadn’t been encouraged to explore before, but he refuses to bang what we would now call the ‘feminist’ drum and turn his play into a piece of political protest.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

2 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House”

This powerful play foretold the 1960’s monumental epic of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, A similar awakening for middle class women, of their unnamed discontent within a marriage. Both paved the the way to the Feminist Movement of the 1970’s where with increased consciousness of economic inequities, women rebelled, just as Nora had done. Homage is owing to both Ibsen in his era and Friedan in hers. Today there are increasing numbers of women serving as Presidents of their nations and in the USA a female Vice-President recently elected to that prestigious office.

I remember reading the play while being a college student. It seemed so sad but at the same time so close to real life. Maybe our lives are quite sad after all.

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

A Doll’s House

Introduction to a doll’s house, summary of a doll’s house by henrik ibsen.

Mrs. Linde then mentions the reason for her arrival. She is seen explaining to Nora how she had to attend to her sick mother and her younger brothers for years. She shares her feeling of emptiness as she doesn’t have a job and hopes Torvald can help her in obtaining employment. Nora then reveals a secret to Mrs. Linde about how she has managed the finances of that trip and has lied to Torvald, saying that she has inherited her father’s money. In fact, she had borrowed the amount without her husband’s consent and now she is struggling to pay it back but believes it will all be over soon.

Meanwhile, Krogstad, a low-level employee at Torvald’s bank, arrives and proceeds to Torvald’s study. His arrival brings discomfort to Nora, but somehow she manages to hide her concern. Dr. Rank also encounters Krogstad and speaks about his bad reputation. Once Torvald ends talking to Krogstad, he comes to the living room and announces that he has decided to give Krogstad’s position to Mrs. Linde. Nora’s children return with their nanny as Dr. Rank, Mrs. Linde and Torvald leave. When Krogstad realizes that he will be replaced, he catches Nora and asks her to influence her husband to let him hold his position. When Nora refuses to help him, he reminds her of how she has committed an offense by forging her father’s signature as a surety for the loan. Frightened, Nora tries to persuade Torvald, but he refuses to listen to her as he tells her how he feels sick in the presence of such people.

It is Christmas and Nora can be seen pacing in the living room alone filled with anxiety. Mrs. Linde enters and helps her sew Nora’s costume for the ball in her neighbor’s house the following evening. Mrs. Linde talks to her about Dr. Rank’s mortal illness. Nora again presses Torvald to retain Krogstad but he is adamant to do so and sends the maid with Krogstad’s letter of dismissal. Next, Dr. Rank arrives after Torvald leaves and Nora thinks about asking him to help her in her struggle with Torvald. But, Dr. Rank reveals that he is in love with her. She dismisses the idea and Krogstad returns after some time with a different approach; he tells Nora that he wants to be appointed in a higher position than before or he will expose her fraud to her husband. He drops a letter detailing her forgery in a letterbox outside her husband’s office.

Major Themes in A Doll’s House

Major characters in a doll’s house, writing style a doll’s house, literary devices used in a doll’s house, related posts:, post navigation.

Dramatic Irony in A Doll's House

The gap between the appearance and reality about Nora's apparently happy life, apparently loving husband, apparently safe and comfortable past and future, and many such appearances are ironical in this drama. There are many instances of irony in the play.

A Doll’s House is full of dramatic irony. For example, Nora expresses her happiness at the beginning of the play by saying that her husband is employed in a higher post and they need not to worry about their future. But, we see that all that was actually the expression of the hidden anxiety for the lack of money to pay off her debts to Krogstad. Nora has been poor. In fact, she is not so conscious of this reality. Ironically, all the troubles and sorrows of Nora begins with her husband promotion and her life is completely shattered at the end. She is unconscious about the future, and of course, we also do not know, that her expectation subsequently goes astray.

The situation when Helmer talks about the moral degradation of Krogstad is also ironical. Helmer explains that Krogstad had committed earlier a forgery and he was crooked by soul. He teaches Nora that she must not ask him to consider Krogstad’s case because such people contaminate their family and children with the influence of their guilt. Though Helmer is ignorant of the fact, Nora and readers come to know that, ironically, all his moral teachings were applicable to his own wife, Nora, who has also committed a similar crime of forgery.

It is also a case of dramatic irony when Helmer says that he will willingly sacrifice his happiness and dignity if some danger were to threaten his wife. But when such a thing happens in the next moment, he turns out to be a complete coward and an utterly egoistic person who will not sacrifice anything at all, in the name of a mere wife. The two dialogues from his own mouths will show the irony; one is his fanciful promise and the other is his response to the ensuing situation.

This is his promise: "Let what will happen, happen. When the real crisis comes, you will not find me lacking in strength or courage. I am man enough to bear the burden for us both."

And this is his response to reality: "How could it help if you were gone from his world? It wouldn't assist me.... I may easily be suspected of having been an accomplice in your crime. People may think... We must appear to be living together... But the children shall be taken out of your hands. I dare no longer entrust them to you."

Nora is unconscious while telling Mrs. Linde that her husband is passionately in love with her, and that he wants her all to himself. This also turns false because she comes to learn at the end that he is very selfish and opportunist. Helmer is not the same what he appears. He appears as a moralist, a teacher, a guardian, a master, a strong man, and so on, but he does not prove any one of them. He scorns Nora accusing and criticizing that she has inherited all bad conducts of her father. How can we attribute sacred moral virtues to him when he himself is ready to buy the blackmailer Krogstad by all his means.

There are many instances of irony, and one more of them is striking. Nora's remark to Helmer that everything he does is quite right is ironical. The speech is ironical because, in the light of what subsequently happens, this speech becomes utterly absurd. Soon it will appear that his much vaunted love for Nora is only a piece of hypocrisy and an illusion and that, more than anything else, he loves himself and the public image of himself.

At the time of rehearsal of the Tarantella, Helmer said to her that she is dancing wildly as if her life depended on the dancing. Nora responds ironically, that her life really does depend on it though Helmer does not understand what she means. Nora counts remaining hours of her life after the rehearsal because she thinks she would sacrifice herself before her husband would sacrifice for her. Both sacrifices never occur and the theme of the play is a twisted irony to the separation and uncertainty of life. Helmer’s “helpless little thing”, Nora, ironically becomes stronger, confident, independent and serious in life. Helmer’s so imagined possession, his little doll, his beautiful treasure becomes ironically a complete stranger to him.

A Doll's House Study Center

Signification of the Slamming of the Door in A Doll's House

Nora's Identity as a Person in A Doll's House

Parallelism and Contrast in A Doll's House

The Plot Construction in A Doll's House

The Significance of the Title A Doll's House

A Doll's House as A Play of Social Criticism

Introduction of A Doll's House

Summary of A Doll's House

Detailed Summary of A Doll's House

Symbolism in A Doll's House

Characterization of Mrs. Nora Helmer

A Doll's House as a Reformist Play

A Doll's House as A Feminist Play

A Doll's House as a Modern Tragedy

Themes in A Doll's House

Biography of Henrik Ibsen

A Doll’s House by Norway’s Henrik Ibsen Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction: Summary

The main theme in a Doll’s House play is feminist of the time. Nora and Helmer is a model husband and wife, living in peace and harmony in their family until Mrs. Linde, an older friend to Nora made a visit in their home in search of a job. Nora manages to secure a job for Mrs. Linde, but unfortunately pushes Mr. Krogstad an accused forger out of his job. Generally, in this play Henrik Ibsen pointedly captures the inferior role of women in Victorian society through his doll motif.

The play ‘A Doll’s House’ is one of the controversial plays, where Nora’s decision actions to dump her kids is contradictory to her thoughts as she thinks that her kids need her more than she needs her own freedom. The author of the play believed that women were made to be mothers and wives.

Moreover, he brings some idea of having an eye for the injustice on the female characters. Although, feminists would later hold him, Ibsen was not an activist of women’s rights; he only handled the problem of women’s right as an aspect of realism within the play.

The key theme of this play is Nora’s insurgence against society and everything that was really expected of her (Ibsen 140). During her era, women were not expected to be self-reliant but were to remain supportive to their husbands, take care of the kids, cook, clean, and make everything perfect around the house.

When Nora took a loan to pay for her husband’s medical bill, this raised a lot of questions and problems in the minds of many individuals from the community, as it was taken as act against the community norms for women to take up a loan without their husbands’ knowledge.

She proved that she was not submissive and helpless as her husband Torvalds thought she was. Thus the author referred her as “poor helpless little creature.” A good example of Torvald thought control and Nora’s submissiveness was when she got him to remind her tarantella, she knew the dance style but she acted as if she needed him to re-teach her everything.

When he said to her “watching you swing and dance the tarantella makes my blood rush” (Ibsen 125), this clearly shows that he is more interested in her physically than emotionally. Then when asked him to stop he said to her, “am I not your husband?” once more this is another example of Torvald’s control over Nora, and how he thinks that Nora is there to fulfill his every desire on command.

Marriage is another aspect that the play addresses; the main message seems to be that, a true working marriage is a joining of equals. In the beginning, Helmers looks happy but as the play progress, the imbalance between them becomes apparent. At the end, their marriage breaks because of lack of misunderstanding among them. They fail to realize themselves and to act as equals. (Johnston 671)

Women and Feminist

Throughout the play, Nora breaks away from the control of her arrogant husband, Torvald. The playwright, Ibsen denies that he wrote a feminist play. Still, throughout the play there is steady talk of women, their traditional roles, and price for them of defying with the traditions. (Johnston 570)

Men and masculinity

Men in this play are trapped by general traditional gender responsibilities. They are seen as the chief providers of the family and they should be in charge of supporting the entire household. Men must be the perfect kings of their respective palace. We see these traditional ideas put across at the end of the play.

Respect and Reputation

The men in this play are occupied with their reputation. Some men have the integrity in their society and do anything to protect it. Even if the play setup is in a living room, the public eye is portrayed through the curtains.

In within the play, ‘A Doll’s House’, the characters spend a lot of time discussing their wealth. Some characters are financially stable and promise for a free flowing money in the future while others struggle to make the end meet. (Ibsen 132)

Love has been given a priority in the play where good time has been used on the topic but in the end, Helmers realize that there was their no true love between them. Romantic love is seen for two of the other characters, but for the main character, true love is pathetic (Ibsen 200).

Dramatic irony

There are some examples in the play where this aspect is used, in Act 1 where Torvald condemns Krogstad for forgery and not coming forward. He also mentions that this action corrupts children’s mind. As a reader, you should know that this is very important to Nora because we know that she had committed forgery in the play and kept it a secret from Torvald. (Johnston 603)

It’s ironic when Torvald says that he pretends Nora is in some kind of trouble, and he waits the time he can rescue her. When the truth is known and Torvald has been given a chance to save Nora, he is all concerned with his reputation (Ibsen 128).

He abused her by calling her names such as featherbrain; he is not interested with rescuing Nora is interested on how he escapes out of this mess without affecting his reputation negatively. Then, when krogstad brings back the IOU document, Torvald shouts that he is rescued and he has forgiven Nora. Ironically, he did not even consider that she had borrowed the money earlier to save him.

Christmas and New Year

The play is set during the holiday period. Its Christmas period for the Helmers and New Year celebration is approaching. Both Christmas and New Year are associated with rebirth and renewal (Johnston 589).

Several characters in the play go through a rebirth process both Nora and Torvald go through a spiritual awakening, which can be taken as a rebirth. When things fail to happen, she realizes that it will not be possible for her to be a fully realized person until she divorces her husband. Finally, at the end of the play Helmer and Nora have been reborn.

Works Cited

Ibsen, Henrik. A Doll’s House . London: Methuen Drama, 2000. Print.

Ibsen, Henrik. A Doll’s House . London: Faber and Faber, 1997. Print.

Johnston, Brian. Ibsen has Selected Plays: A Norton Critical Edition . New York: W.W. Norton, 2004. Print.

Further Study: FAQ

📌 what is a doll’s house summary, 📌 what are the key a doll’s house themes, 📌 what kind of person is nora in a doll’s house, 📌 what does krogstad represent in a doll’s house.

- Lost Star of Myth and Time

- Heroes after the Middle Ages

- Relationships in “A Doll’s House” by Henrik Ibsen

- The Interpretation of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll's House Presented by Patrick Garland

- Freedom in Henrik Ibsen’s "A Doll’s House" Literature Analysis

- Elementary Children’s Literature: Infancy through Age 13

- Literary Techniques used by Ida B. Wells in her A Red Record

- The New Science by Vico

- The Voice of Faulkner

- The Hardboiled Qualities and Features in Detective Stories

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 25). A Doll's House by Norway's Henrik Ibsen. https://ivypanda.com/essays/a-doll-house/

"A Doll's House by Norway's Henrik Ibsen." IvyPanda , 25 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/a-doll-house/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'A Doll's House by Norway's Henrik Ibsen'. 25 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "A Doll's House by Norway's Henrik Ibsen." October 25, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/a-doll-house/.

1. IvyPanda . "A Doll's House by Norway's Henrik Ibsen." October 25, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/a-doll-house/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "A Doll's House by Norway's Henrik Ibsen." October 25, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/a-doll-house/.

Home / Essay Samples / Literature / A Doll's House / “A Doll’s House” Analysis: The Role of Deception and Betrayal

“A Doll's House” Analysis: The Role of Deception and Betrayal

- Category: Literature

- Topic: A Doll's House , Character

Pages: 4 (1779 words)

Views: 5287

- Downloads: -->

A Doll's House literary analysis (essay)

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Metamorphosis Essays

Their Eyes Were Watching God Essays

The Things They Carried Essays

A Modest Proposal Essays

A Rose For Emily Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->