- Bihar Board

SRM University

Wb 12th result 2024.

- CBSE 10th Result 2024

- CBSE 12th Result 2024

- WB Board Result 2024

- CG Board Result 2024

- Kerala Board Result 2024

- MBOSE Result 2024

- Shiv Khera Special

- Education News

- Web Stories

- Current Affairs

- नए भारत का नया उत्तर प्रदेश

- School & Boards

- College Admission

- Govt Jobs Alert & Prep

- GK & Aptitude

- general knowledge in hindi

भारत में राज्यवार अक्षय ऊर्जा उत्पादन की स्थिति क्या है?

नवीन एवं नवीकरणीय ऊर्जा मंत्रालय द्वारा जारी आंकड़ों के मुताबिक, भारत की कुल अक्षय ऊर्जा उत्पादन क्षमता 896602 मेगावाट है. राजस्थान सौर ऊर्जा उत्पादन और देश में कुल अक्षय ऊर्जा उत्पादन का सबसे बड़ा उत्पादक है, इसके बाद 118208 मेगावाट उत्पादन क्षमता के साथ जम्मू और कश्मीर दूसरे और 74500 मेगावाट अक्षय ऊर्जा का उत्पादन करके महाराष्ट्र तीसरे स्थान पर है.

ऊर्जा के नवीकरणीय स्रोतों में वे स्रोत शामिल किये जाते हैं जो कि एक बार इस्तेमाल हो जाने पर दुबारा इस्तेमाल करने लायक हो जाते हैं. नवीकरणीय उर्जा/ अक्षय ऊर्जा स्रोतों के नाम हैं; सूर्य ऊर्जा, पनचक्की उर्जा, भूतापीय ऊर्जा और बायोमास (इसमें इथेनॉल, बायोडीजल आते हैं).

Sources: Ministry of New and Renewable Energy

भारत में अक्षय ऊर्जा से संबंधित महत्वपूर्ण तथ्य :

1. भारत का अक्षय ऊर्जा सेक्टर दुनिया में दूसरा सबसे आकर्षक अक्षय ऊर्जा का बाजार है.

2 . कुल स्थापित पवन ऊर्जा क्षमता के मामले में भारत दुनिया में चौथे स्थान पर है.

3 . जनवरी से नवंबर 2017 तक; भारत ने अक्षय स्रोतों से लगभग 12 गीगावॉट बिजली उत्पादन किया है.

4. वर्तमान में भारत के पास नवीकरणीय स्रोतों (Renewable sources) से 58.30 गीगावाट उर्जा उत्पादन की क्षमता है जो कि भारत की कुल ऊर्जा उत्पादन का लगभग 18.5% है.

5. भारत की कुल सौर उर्जा उत्पादन क्षमता 2035 तक वैश्विक सौर क्षमता का 8% होने की उम्मीद है.

6. भारत में कुल 148518 मेगावाट “अक्षय उर्जा” उत्पादन और 142310 मेगावाट “सौर ऊर्जा” उत्पादन के साथ राजस्थान पूरे देश में सबसे पहला स्थान रखता है.

निष्कर्ष में यह कहा जा सकता है कि भारत शीध्र ही अक्षय उर्जा के क्षेत्र में दुनिया में एक उत्कृष्ट स्थान हासिल कर लेगा और हाल ही में नई दिल्ली में संपन्न “अंतर्राष्ट्रीय सौर एलायंस” शिखर सम्मेलन इसका बहुत बड़ा सबूत है.

आप जागरण जोश पर भारत , विश्व समाचार, खेल के साथ-साथ प्रतियोगी परीक्षाओं की तैयारी के लिए समसामयिक सामान्य ज्ञान , सूची, जीके हिंदी और क्विज प्राप्त कर सकते है. आप यहां से कर्रेंट अफेयर्स ऐप डाउनलोड करें.

- राजस्थान दिवस

- Indian Team for T20 World Cup

- BCCI Central Contract 2024

- राजस्थान के मुख्यमंत्री

- क्रिकेट वर्ल्ड कप 2027

- Holi Kab Hai

- बीएसईबी बिहार बोर्ड इंटर रिजल्ट

- HP Board 12th Result 2024 Roll Number

- HPBOSE 12th Result 2024

- भारतीय अर्थव्यवस्था

- भारतीय अर्थव्यवस्था के आयाम

Latest Education News

Picture Puzzles IQ Test: Only 1% With Sharpest Eyes Can Spot the Hidden Ring In 8 Seconds!

CGBSE 10th, 12th Result 2024: छत्तीसगढ़ बोर्ड के नतीजे cgbse.nic.in पर कल दोपहर 12:30 बजे, सिर्फ इन दो वेबसाइट पर मिलेगा डायरेक्ट लिंक

[Official] GSEB HSC Results 2024 Date and Time: Check Gujarat Board 12th Result Notice, How to Download Online

[Official] HS Result 2024 Assam Date and Time Announced: Check Notice for AHSEC 12th Results Here

Brain Teaser: Only Geniuses Can Solve This Hidden Number Puzzle

SSLC Result 2024 Karnataka LIVE: KSEAB Class 10 Scores Releasing on May 9 at kseab.karnataka.gov.in, karresults.nic.in, Check Online by Registration Number

UGC NET Commerce Syllabus 2024: PDF Download, Check Important Topics and Exam Pattern

ISC Class 11th Environmental Science Syllabus 2024-25: Download Full Curriculum

TSPSC Group 1 Important Questions for General Studies (GS) with Answers

Is Google's Search Throne Under Threat? OpenAI Works on Search Feature for ChatGPT

ISC Class 11th Biotechnology Syllabus 2024-25: Download PDF for ISC Class 11 Complete syllabus

UPSC NDA Results 2024: Check NDA 1 Exam Result Update, List of selected Candidates, and Marks soon at upsc.gov.in

CGBSE Board Result 2024: Chhattisgarh Class 10, 12 Result Date, Time, Latest News And Official Website at cgbse.nic.in

CGBSE 10th, 12th Results 2024 On May 9, Check List of Websites Here

CGBSE 12th Result 2024: Chhattisgarh Board 12 रिजल्ट Date, Latest News And Official Website at cgbse.nic.in

CGBSE 10th Result 2024: Chhattisgarh Board 10 रिजल्ट Date, Time, Latest News And Official Website at cgbse.nic.in

Karnataka SSLC Result 2024: KSEAB 10th Result Date and Time at karresults.nic.in

CGBSE 12th Voc Result 2024: Chhattisgarh Board 12th Voc Exam Date and Expected Result Dates at cgbse.nic.in, results.cg.nic.in

Kerala Plus Two Result 2024: DHSE Class 12th Result Date and Time at keralaresults.nic.in

School Assembly News Headlines (9 May): Election 2024, Narendra Modi Kejriwal Case, Sam Pitroda, Mother Day, Akash Anand, Heatwaves, NASA, and Other News in English

Renewable Energy: रिन्यूएबल एनर्जी क्या होती है? सौर ऊर्जा से अलग यह कितने प्रकार की होती है?

रिन्यूएबल एनर्जी को अक्षय ऊर्जा या नवीनीकरण ऊर्जा कहते हैं. इस ऊर्जा के भंडार असीमित हैं, इन्हे समाप्त नहीं किया जा सकता. इस ऊर्जा को लगातार उत्त्पन किया जा सकता है, इसीलिए इसे अक्षय ऊर्जा कहते हैं..

नवीकरणीय ऊर्जा स्रोत

जनरल नॉलेज फोटो गैलरी

जनरल नॉलेज वेब स्टोरीज

ट्रेडिंग न्यूज

टॉप हेडलाइंस

ट्रेडिंग ओपीनियन

पर्सनल कार्नर

- Open access

- Published: 07 January 2020

Renewable energy for sustainable development in India: current status, future prospects, challenges, employment, and investment opportunities

- Charles Rajesh Kumar. J ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2354-6463 1 &

- M. A. Majid 1

Energy, Sustainability and Society volume 10 , Article number: 2 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

421k Accesses

258 Citations

83 Altmetric

Metrics details

The primary objective for deploying renewable energy in India is to advance economic development, improve energy security, improve access to energy, and mitigate climate change. Sustainable development is possible by use of sustainable energy and by ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for citizens. Strong government support and the increasingly opportune economic situation have pushed India to be one of the top leaders in the world’s most attractive renewable energy markets. The government has designed policies, programs, and a liberal environment to attract foreign investments to ramp up the country in the renewable energy market at a rapid rate. It is anticipated that the renewable energy sector can create a large number of domestic jobs over the following years. This paper aims to present significant achievements, prospects, projections, generation of electricity, as well as challenges and investment and employment opportunities due to the development of renewable energy in India. In this review, we have identified the various obstacles faced by the renewable sector. The recommendations based on the review outcomes will provide useful information for policymakers, innovators, project developers, investors, industries, associated stakeholders and departments, researchers, and scientists.

Introduction

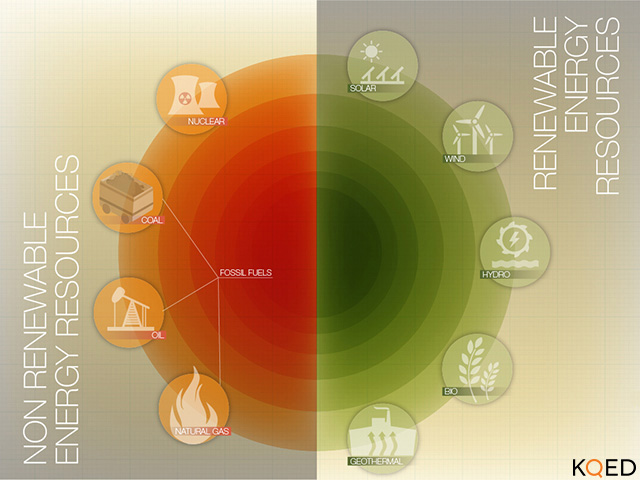

The sources of electricity production such as coal, oil, and natural gas have contributed to one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions. It is essential to raise the standard of living by providing cleaner and more reliable electricity [ 1 ]. India has an increasing energy demand to fulfill the economic development plans that are being implemented. The provision of increasing quanta of energy is a vital pre-requisite for the economic growth of a country [ 2 ]. The National Electricity Plan [NEP] [ 3 ] framed by the Ministry of Power (MoP) has developed a 10-year detailed action plan with the objective to provide electricity across the country, and has prepared a further plan to ensure that power is supplied to the citizens efficiently and at a reasonable cost. According to the World Resource Institute Report 2017 [ 4 , 5 ], India is responsible for nearly 6.65% of total global carbon emissions, ranked fourth next to China (26.83%), the USA (14.36%), and the EU (9.66%). Climate change might also change the ecological balance in the world. Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) have been submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement. The latter has hoped to achieve the goal of limiting the rise in global temperature to well below 2 °C [ 6 , 7 ]. According to a World Energy Council [ 8 ] prediction, global electricity demand will peak in 2030. India is one of the largest coal consumers in the world and imports costly fossil fuel [ 8 ]. Close to 74% of the energy demand is supplied by coal and oil. According to a report from the Center for monitoring Indian economy, the country imported 171 million tons of coal in 2013–2014, 215 million tons in 2014–2015, 207 million tons in 2015–2016, 195 million tons in 2016–2017, and 213 million tons in 2017–2018 [ 9 ]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to find alternate sources for generating electricity.

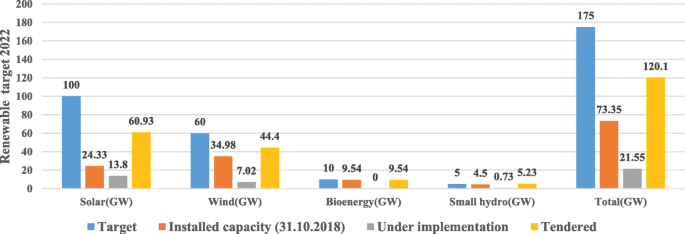

In this way, the country will have a rapid and global transition to renewable energy technologies to achieve sustainable growth and avoid catastrophic climate change. Renewable energy sources play a vital role in securing sustainable energy with lower emissions [ 10 ]. It is already accepted that renewable energy technologies might significantly cover the electricity demand and reduce emissions. In recent years, the country has developed a sustainable path for its energy supply. Awareness of saving energy has been promoted among citizens to increase the use of solar, wind, biomass, waste, and hydropower energies. It is evident that clean energy is less harmful and often cheaper. India is aiming to attain 175 GW of renewable energy which would consist of 100 GW from solar energy, 10 GW from bio-power, 60 GW from wind power, and 5 GW from small hydropower plants by the year 2022 [ 11 ]. Investors have promised to achieve more than 270 GW, which is significantly above the ambitious targets. The promises are as follows: 58 GW by foreign companies, 191 GW by private companies, 18 GW by private sectors, and 5 GW by the Indian Railways [ 12 ]. Recent estimates show that in 2047, solar potential will be more than 750 GW and wind potential will be 410 GW [ 13 , 14 ]. To reach the ambitious targets of generating 175 GW of renewable energy by 2022, it is essential that the government creates 330,000 new jobs and livelihood opportunities [ 15 , 16 ].

A mixture of push policies and pull mechanisms, accompanied by particular strategies should promote the development of renewable energy technologies. Advancement in technology, proper regulatory policies [ 17 ], tax deduction, and attempts in efficiency enhancement due to research and development (R&D) [ 18 ] are some of the pathways to conservation of energy and environment that should guarantee that renewable resource bases are used in a cost-effective and quick manner. Hence, strategies to promote investment opportunities in the renewable energy sector along with jobs for the unskilled workers, technicians, and contractors are discussed. This article also manifests technological and financial initiatives [ 19 ], policy and regulatory framework, as well as training and educational initiatives [ 20 , 21 ] launched by the government for the growth and development of renewable energy sources. The development of renewable technology has encountered explicit obstacles, and thus, there is a need to discuss these barriers. Additionally, it is also vital to discover possible solutions to overcome these barriers, and hence, proper recommendations have been suggested for the steady growth of renewable power [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Given the enormous potential of renewables in the country, coherent policy measures and an investor-friendly administration might be the key drivers for India to become a global leader in clean and green energy.

Projection of global primary energy consumption

An energy source is a necessary element of socio-economic development. The increasing economic growth of developing nations in the last decades has caused an accelerated increase in energy consumption. This trend is anticipated to grow [ 25 ]. A prediction of future power consumption is essential for the investigation of adequate environmental and economic policies [ 26 ]. Likewise, an outlook to future power consumption helps to determine future investments in renewable energy. Energy supply and security have not only increased the essential issues for the development of human society but also for their global political and economic patterns [ 27 ]. Hence, international comparisons are helpful to identify past, present, and future power consumption.

Table 1 shows the primary energy consumption of the world, based on the BP Energy Outlook 2018 reports. In 2016, India’s overall energy consumption was 724 million tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe) and is expected to rise to 1921 Mtoe by 2040 with an average growth rate of 4.2% per annum. Energy consumption of various major countries comprises commercially traded fuels and modern renewables used to produce power. In 2016, India was the fourth largest energy consumer in the world after China, the USA, and the Organization for economic co-operation and development (OECD) in Europe [ 29 ].

The projected estimation of global energy consumption demonstrates that energy consumption in India is continuously increasing and retains its position even in 2035/2040 [ 28 ]. The increase in India’s energy consumption will push the country’s share of global energy demand to 11% by 2040 from 5% in 2016. Emerging economies such as China, India, or Brazil have experienced a process of rapid industrialization, have increased their share in the global economy, and are exporting enormous volumes of manufactured products to developed countries. This shift of economic activities among nations has also had consequences concerning the country’s energy use [ 30 ].

Projected primary energy consumption in India

The size and growth of a country’s population significantly affects the demand for energy. With 1.368 billion citizens, India is ranked second, of the most populous countries as of January 2019 [ 31 ]. The yearly growth rate is 1.18% and represents almost 17.74% of the world’s population. The country is expected to have more than 1.383 billion, 1.512 billion, 1.605 billion, 1.658 billion people by the end of 2020, 2030, 2040, and 2050, respectively. Each year, India adds a higher number of people to the world than any other nation and the specific population of some of the states in India is equal to the population of many countries.

The growth of India’s energy consumption will be the fastest among all significant economies by 2040, with coal meeting most of this demand followed by renewable energy. Renewables became the second most significant source of domestic power production, overtaking gas and then oil, by 2020. The demand for renewables in India will have a tremendous growth of 256 Mtoe in 2040 from 17 Mtoe in 2016, with an annual increase of 12%, as shown in Table 2 .

Table 3 shows the primary energy consumption of renewables for the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) from 2016 to 2040. India consumed around 17 Mtoe of renewable energy in 2016, and this will be 256 Mtoe in 2040. It is probable that India’s energy consumption will grow fastest among all major economies by 2040, with coal contributing most in meeting this demand followed by renewables. The percentage share of renewable consumption in 2016 was 2% and is predicted to increase by 13% by 2040.

How renewable energy sources contribute to the energy demand in India

Even though India has achieved a fast and remarkable economic growth, energy is still scarce. Strong economic growth in India is escalating the demand for energy, and more energy sources are required to cover this demand. At the same time, due to the increasing population and environmental deterioration, the country faces the challenge of sustainable development. The gap between demand and supply of power is expected to rise in the future [ 32 ]. Table 4 presents the power supply status of the country from 2009–2010 to 2018–2019 (until October 2018). In 2018, the energy demand was 1,212,134 GWh, and the availability was 1,203,567 GWh, i.e., a deficit of − 0.7% [ 33 ].

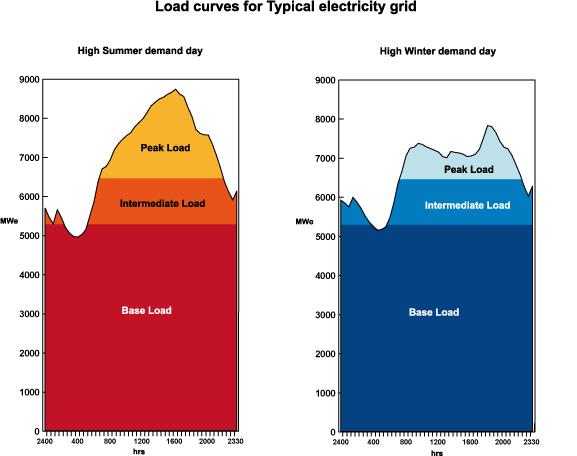

According to the Load generation and Balance Report (2016–2017) of the Central Electricity Authority of India (CEA), the electrical energy demand for 2021–2022 is anticipated to be at least 1915 terawatt hours (TWh), with a peak electric demand of 298 GW [ 34 ]. Increasing urbanization and rising income levels are responsible for an increased demand for electrical appliances, i.e., an increased demand for electricity in the residential sector. The increased demand in materials for buildings, transportation, capital goods, and infrastructure is driving the industrial demand for electricity. An increased mechanization and the shift to groundwater irrigation across the country is pushing the pumping and tractor demand in the agriculture sector, and hence the large diesel and electricity demand. The penetration of electric vehicles and the fuel switch to electric and induction cook stoves will drive the electricity demand in the other sectors shown in Table 5 .

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), a quarter of India’s energy demand can be met with renewable energy. The country could potentially increase its share of renewable power generation to over one-third by 2030 [ 35 ].

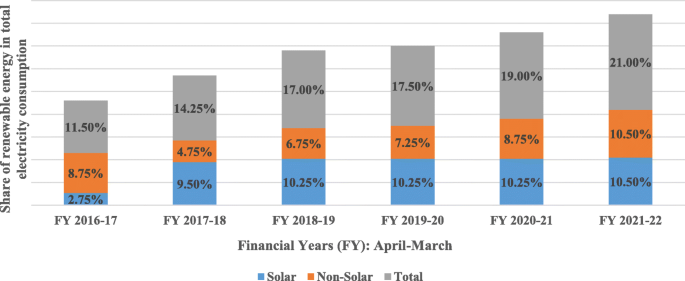

Table 6 presents the estimated contribution of renewable energy sources to the total energy demand. MoP along with CEA in its draft national electricity plan for 2016 anticipated that with 175 GW of installed capacity of renewable power by 2022, the expected electricity generation would be 327 billion units (BUs), which would contribute to 1611 BU energy requirements. This indicates that 20.3% of the energy requirements would be fulfilled by renewable energy by 2022 and 24.2% by 2027 [ 36 ]. Figure 1 shows the ambitious new target for the share of renewable energy in India’s electricity consumption set by MoP. As per the order of revised RPO (Renewable Purchase Obligations, legal act of June 2018), the country has a target of a 21% share of renewable energy in its total electricity consumption by March 2022. In 2014, the same goal was at 15% and increased to 21% by 2018. It is India’s goal to reach 40% renewable sources by 2030.

Target share of renewable energy in India’s power consumption

Estimated renewable energy potential in India

The estimated potential of wind power in the country during 1995 [ 37 ] was found to be 20,000 MW (20 GW), solar energy was 5 × 10 15 kWh/pa, bioenergy was 17,000 MW, bagasse cogeneration was 8000 MW, and small hydropower was 10,000 MW. For 2006, the renewable potential was estimated as 85,000 MW with wind 4500 MW, solar 35 MW, biomass/bioenergy 25,000 MW, and small hydropower of 15,000 MW [ 38 ]. According to the annual report of the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) for 2017–2018, the estimated potential of wind power was 302.251 GW (at 100-m mast height), of small hydropower 19.749 GW, biomass power 17.536 GW, bagasse cogeneration 5 GW, waste to energy (WTE) 2.554 GW, and solar 748.990 GW. The estimated total renewable potential amounted to 1096.080 GW [ 39 ] assuming 3% wasteland, which is shown in Table 7 . India is a tropical country and receives significant radiation, and hence the solar potential is very high [ 40 , 41 , 42 ].

Gross installed capacity of renewable energy in India

As of June 2018 reports, the country intends to reach 225 GW of renewable power capacity by 2022 exceeding the target of 175 GW pledged during the Paris Agreement. The sector is the fourth most attractive renewable energy market in the world. As in October 2018, India ranked fifth in installed renewable energy capacity [ 43 ].

Gross installed capacity of renewable energy—according to region

Table 8 lists the cumulative installed capacity of both conventional and renewable energy sources. The cumulative installed capacity of renewable sources as on the 31 st of December 2018 was 74081.66 MW. Renewable energy (small hydropower, wind, biomass, WTE, solar) accounted for an approximate 21% share of the cumulative installed power capacity, and the remaining 78.791% originated from other conventional sources (coal, gas diesel, nuclear, and large hydropower) [ 44 ]. The best regions for renewable energy are the southern states that have the highest solar irradiance and wind in the country. When renewable energy alone is considered for analysis, the Southern region covers 49.121% of the cumulative installed renewable capacity, followed by the Western region (29.742%), the Northern region (18.890%), the Eastern region (1.836%), the North-Easter region 0.394%, and the Islands (0.017%). As far as conventional energy is concerned, the Western region with 33.452% ranks first and is followed by the Northern region with 28.484%, the Southern region (24.967%), the Eastern region (11.716%), the Northern-Eastern (1.366%), and the Islands (0.015%).

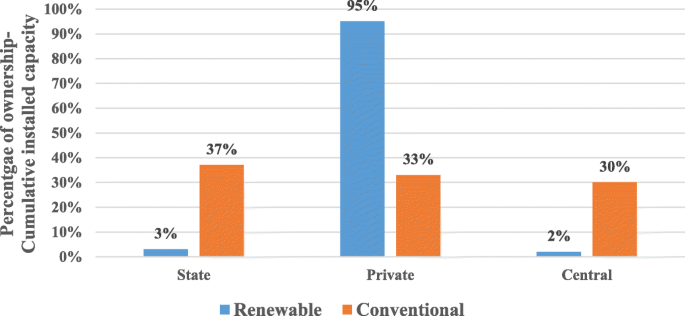

Gross installed capacity of renewable energy—according to ownership

State government, central government, and private players drive the Indian energy sector. The private sector leads the way in renewable energy investment. Table 9 shows the installed gross renewable energy and conventional energy capacity (percentage)—ownership wise. It is evident from Fig. 2 that 95% of the installed renewable capacity derives from private companies, 2% from the central government, and 3% from the state government. The top private companies in the field of non-conventional energy generation are Tata Power Solar, Suzlon, and ReNew Power. Tata Power Solar System Limited are the most significant integrated solar power players in the country, Suzlon realizes wind energy projects, and ReNew Power Ventures operate with solar and wind power.

Gross renewable energy installed capacity (percentage)—Ownership wise as per the 31.12.2018 [ 43 ]

Gross installed capacity of renewable energy—state wise

Table 10 shows the installed capacity of cumulative renewable energy (state wise), out of the total installed capacity of 74,081.66 MW, where Karnataka ranks first with 12,953.24 MW (17.485%), Tamilnadu second with 11,934.38 MW (16%), Maharashtra third with 9283.78 MW (12.532%), Gujarat fourth with 10.641 MW (10.641%), and Rajasthan fifth with 7573.86 MW (10.224%). These five states cover almost 66.991% of the installed capacity of total renewable. Other prominent states are Andhra Pradesh (9.829%), Madhya Pradesh (5.819%), Telangana (5.137%), and Uttar Pradesh (3.879%). These nine states cover almost 91.655%.

Gross installed capacity of renewable energy—according to source

Under union budget of India 2018–2019, INR 3762 crore (USD 581.09 million), was allotted for grid-interactive renewable power schemes and projects. As per the 31.12.2018, the installed capacity of total renewable power (excluding large hydropower) in the country amounted to 74.08166 GW. Around 9.363 GW of solar energy, 1.766 GW of wind, 0.105 GW of small hydropower (SHP), and biomass power of 8.7 GW capacity were added in 2017–2018. Table 11 shows the installed capacity of renewable energy over the last 10 years until the 31.12.2018. Wind energy continues to dominate the countries renewable energy industry, accounting for over 47% of cumulative installed renewable capacity (35,138.15 MW), followed by solar power of 34% (25,212.26 MW), biomass power/cogeneration of 12% (9075.5 MW), and small hydropower of 6% (4517.45 MW). In the renewable energy country attractiveness index (RECAI) of 2018, India ranked in fourth position. The installed renewable energy production capacity has grown at an accelerated pace over the preceding few years, posting a CAGR of 19.78% between 2014 and 2018 [ 45 ] .

Estimation of the installed capacity of renewable energy

Table 12 gives the share of installed cumulative renewable energy capacity, in comparison with the installed conventional energy capacity. In 2022 and 2032, the installed renewable energy capacity will account for 32% and 35%, respectively [ 46 , 47 ]. The most significant renewable capacity expansion program in the world is being taken up by India. The government is preparing to boost the percentage of clean energy through a tremendous push in renewables, as discussed in the subsequent sections.

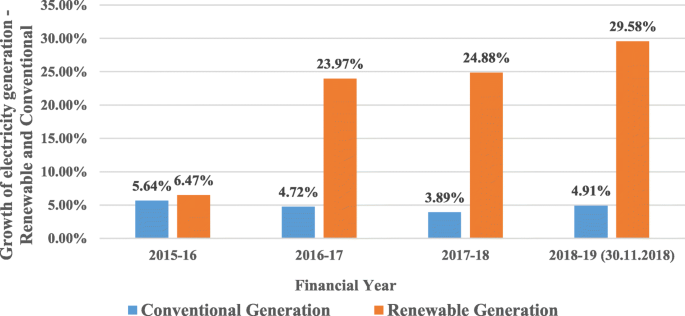

Gross electricity generation from renewable energy in India

The overall generation (including the generation from grid-connected renewable sources) in the country has grown exponentially. Between 2014–2015 and 2015–2016, it achieved 1110.458 BU and 1173.603 BU, respectively. The same was recorded with 1241.689 BU and 1306.614 BU during 2015–2016 and 1306.614 BU from 2016–2017 and 2017–2018, respectively. Figure 3 indicates that the annual renewable power production increased faster than the conventional power production. The rise accounted for 6.47% in 2015–2016 and 24.88% in 2017–2018, respectively. Table 13 compares the energy generation from traditional sources with that from renewable sources. Remarkably, the energy generation from conventional sources reached 811.143 BU and from renewable sources 9.860 BU in 2010 compared to 1.206.306 BU and 88.945 BU in 2017, respectively [ 48 ]. It is observed that the price of electricity production using renewable technologies is higher than that for conventional generation technologies, but is likely to fall with increasing experience in the techniques involved [ 49 ].

The annual growth in power generation as per the 30th of November 2018

Gross electricity generation from renewable energy—according to regions

Table 14 shows the gross electricity generation from renewable energy-region wise. It is noted that the highest renewable energy generation derives from the southern region, followed by the western part. As of November 2018, 50.33% of energy generation was obtained from the southern area and 29.37%, 18.05%, 2%, and 0.24% from Western, Northern, North-Eastern Areas, and the Island, respectively.

Gross electricity generation from renewable energy—according to states

Table 15 shows the gross electricity generation from renewable energy—region-wise. It is observed that the highest renewable energy generation was achieved from Karnataka (16.57%), Tamilnadu (15.82%), Andhra Pradesh (11.92%), and Gujarat (10.87%) as per November 2018. While adding four years from 2015–2016 to 2018–2019 Tamilnadu [ 50 ] remains in the first position followed by Karnataka, Maharashtra, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh.

Gross electricity generation from renewable energy—according to sources

Table 16 shows the gross electricity generation from renewable energy—source-wise. It can be concluded from the table that the wind-based energy generation as per 2017–2018 is most prominent with 51.71%, followed by solar energy (25.40%), Bagasse (11.63%), small hydropower (7.55%), biomass (3.34%), and WTE (0.35%). There has been a constant increase in the generation of all renewable sources from 2014–2015 to date. Wind energy, as always, was the highest contributor to the total renewable power production. The percentage of solar energy produced in the overall renewable power production comes next to wind and is typically reduced during the monsoon months. The definite improvement in wind energy production can be associated with a “good” monsoon. Cyclonic action during these months also facilitates high-speed winds. Monsoon winds play a significant part in the uptick in wind power production, especially in the southern states of the country.

Estimation of gross electricity generation from renewable energy

Table 17 shows an estimation of gross electricity generation from renewable energy based on the 2015 report of the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog) [ 51 ]. It is predicted that the share of renewable power will be 10.2% by 2022, but renewable power technologies contributed a record of 13.4% to the cumulative power production in India as of the 31st of August 2018. The power ministry report shows that India generated 122.10 TWh and out of the total electricity produced, renewables generated 16.30 TWh as on the 31st of August 2018. According to the India Brand Equity Foundation report, it is anticipated that by the year 2040, around 49% of total electricity will be produced using renewable energy.

Current achievements in renewable energy 2017–2018

India cares for the planet and has taken a groundbreaking journey in renewable energy through the last 4 years [ 52 , 53 ]. A dedicated ministry along with financial and technical institutions have helped India in the promotion of renewable energy and diversification of its energy mix. The country is engaged in expanding the use of clean energy sources and has already undertaken several large-scale sustainable energy projects to ensure a massive growth of green energy.

1. India doubled its renewable power capacity in the last 4 years. The cumulative renewable power capacity in 2013–2014 reached 35,500 MW and rose to 70,000 MW in 2017–2018.

2. India stands in the fourth and sixth position regarding the cumulative installed capacity in the wind and solar sector, respectively. Furthermore, its cumulative installed renewable capacity stands in fifth position globally as of the 31st of December 2018.

3. As said above, the cumulative renewable energy capacity target for 2022 is given as 175 GW. For 2017–2018, the cumulative installed capacity amounted to 70 GW, the capacity under implementation is 15 GW and the tendered capacity was 25 GW. The target, the installed capacity, the capacity under implementation, and the tendered capacity are shown in Fig. 4 .

4. There is tremendous growth in solar power. The cumulative installed solar capacity increased by more than eight times in the last 4 years from 2.630 GW (2013–2014) to 22 GW (2017–2018). As of the 31st of December 2018, the installed capacity amounted to 25.2122 GW.

5. The renewable electricity generated in 2017–2018 was 101839 BUs.

6. The country published competitive bidding guidelines for the production of renewable power. It also discovered the lowest tariff and transparent bidding method and resulted in a notable decrease in per unit cost of renewable energy.

7. In 21 states, there are 41 solar parks with a cumulative capacity of more than 26,144 MW that have already been approved by the MNRE. The Kurnool solar park was set up with 1000 MW; and with 2000 MW the largest solar park of Pavagada (Karnataka) is currently under installation.

8. The target for solar power (ground mounted) for 2018–2019 is given as 10 GW, and solar power (Rooftop) as 1 GW.

9. MNRE doubled the target for solar parks (projects of 500 MW or more) from 20 to 40 GW.

10. The cumulative installed capacity of wind power increased by 1.6 times in the last 4 years. In 2013–2014, it amounted to 21 GW, from 2017 to 2018 it amounted to 34 GW, and as of 31st of December 2018, it reached 35.138 GW. This shows that achievements were completed in wind power use.

11. An offshore wind policy was announced. Thirty-four companies (most significant global and domestic wind power players) competed in the “expression of interest” (EoI) floated on the plan to set up India’s first mega offshore wind farm with a capacity of 1 GW.

12. 682 MW small hydropower projects were installed during the last 4 years along with 600 watermills (mechanical applications) and 132 projects still under development.

13. MNRE is implementing green energy corridors to expand the transmission system. 9400 km of green energy corridors are completed or under implementation. The cost spent on it was INR 10141 crore (101,410 Million INR = 1425.01 USD). Furthermore, the total capacity of 19,000 MVA substations is now planned to be complete by March 2020.

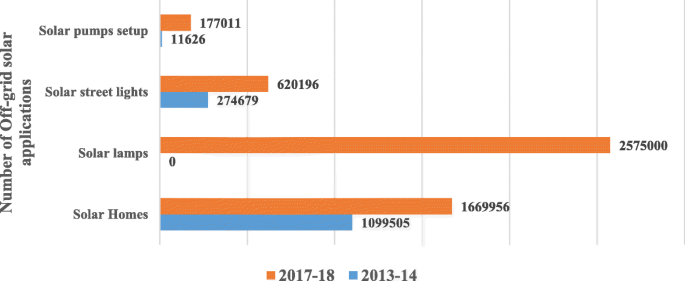

14. MNRE is setting up solar pumps (off-grid application), where 90% of pumps have been set up as of today and between 2014–2015 and 2017–2018. Solar street lights were more than doubled. Solar home lighting systems have been improved by around 1.5 times. More than 2,575,000 solar lamps have been distributed to students. The details are illustrated in Fig. 5 .

15. From 2014–2015 to 2017–2018, more than 2.5 lakh (0.25 million) biogas plants were set up for cooking in rural homes to enable families by providing them access to clean fuel.

16. New policy initiatives revised the tariff policy mandating purchase and generation obligations (RPO and RGO). Four wind and solar inter-state transmission were waived; charges were planned, the RPO trajectory for 2022 and renewable energy policy was finalized.

17. Expressions of interest (EoI) were invited for installing solar photovoltaic manufacturing capacities associated with the guaranteed off-take of 20 GW. EoI indicated 10 GW floating solar energy plants.

18. Policy for the solar-wind hybrid was announced. Tender for setting up 2 GW solar-wind hybrid systems in existing projects was invited.

19. To facilitate R&D in renewable power technology, a National lab policy on testing, standardization, and certification was announced by the MNRE.

20. The Surya Mitra program was conducted to train college graduates in the installation, commissioning, operations, and management of solar panels. The International Solar Alliance (ISA) headquarters in India (Gurgaon) will be a new commencement for solar energy improvement in India.

21. The renewable sector has become considerably more attractive for foreign and domestic investors, and the country expects to attract up to USD 80 billion in the next 4 years from 2018–2019 to 2021–2022.

22. The solar power capacity expanded by more than eight times from 2.63 GW in 2013–2014 to 22 GW in 2017–2018.

23. A bidding for 115 GW renewable energy projects up to March 2020 was announced.

24. The Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) acting for system/components of solar PV was established.

25. To recognize and encourage innovative ideas in renewable energy sectors, the Government provides prizes and awards. Creative ideas/concepts should lead to prototype development. The Name of the award is “Abhinav Soch-Nayi Sambhawanaye,” which means Innovative ideas—New possibilities.

Renewable energy target, installed capacity, under implementation and tendered [ 52 ]

Off-grid solar applications [ 52 ]

Solar energy

Under the National Solar Mission, the MNRE has updated the objective of grid-connected solar power projects from 20 GW by the year 2021–2022 to 100 GW by the year 2021–2022. In 2008–2009, it reached just 6 MW. The “Made in India” initiative to promote domestic manufacturing supported this great height in solar installation capacity. Currently, India has the fifth highest solar installed capacity worldwide. By the 31st of December 2018, solar energy had achieved 25,212.26 MW against the target of 2022, and a further 22.8 GW of capacity has been tendered out or is under current implementation. MNRE is preparing to bid out the remaining solar energy capacity every year for the periods 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 so that bidding may contribute with 100 GW capacity additions by March 2020. In this way, 2 years for the completion of projects would remain. Tariffs will be determined through the competitive bidding process (reverse e-auction) to bring down tariffs significantly. The lowest solar tariff was identified to be INR 2.44 per kWh in July 2018. In 2010, solar tariffs amounted to INR 18 per kWh. Over 100,000 lakh (10,000 million) acres of land had been classified for several planned solar parks, out of which over 75,000 acres had been obtained. As of November 2018, 47 solar parks of a total capacity of 26,694 MW were established. The aggregate capacity of 4195 MW of solar projects has been commissioned inside various solar parks (floating solar power). Table 18 shows the capacity addition compared to the target. It indicates that capacity addition increased exponentially.

Wind energy

As of the 31st of December 2018, the total installed capacity of India amounted to 35,138.15 MW compared to a target of 60 GW by 2022. India is currently in fourth position in the world for installed capacity of wind power. Moreover, around 9.4 GW capacity has been tendered out or is under current implementation. The MNRE is preparing to bid out for A 10 GW wind energy capacity every year for 2018–2019 and 2019–2020, so that bidding will allow for 60 GW capacity additions by March 2020, giving the remaining two years for the accomplishment of the projects. The gross wind energy potential of the country now reaches 302 GW at a 100 m above-ground level. The tariff administration has been changed from feed-in-tariff (FiT) to the bidding method for capacity addition. On the 8th of December 2017, the ministry published guidelines for a tariff-based competitive bidding rule for the acquisition of energy from grid-connected wind energy projects. The developed transparent process of bidding lowered the tariff for wind power to its lowest level ever. The development of the wind industry has risen in a robust ecosystem ensuring project execution abilities and a manufacturing base. State-of-the-art technologies are now available for the production of wind turbines. All the major global players in wind power have their presence in India. More than 12 different companies manufacture more than 24 various models of wind turbines in India. India exports wind turbines and components to the USA, Europe, Australia, Brazil, and other Asian countries. Around 70–80% of the domestic production has been accomplished with strong domestic manufacturing companies. Table 19 lists the capacity addition compared to the target for the capacity addition. Furthermore, electricity generation from the wind-based capacity has improved, even though there was a slowdown of new capacity in the first half of 2018–2019 and 2017–2018.

The national energy storage mission—2018

The country is working toward a National Energy Storage Mission. A draft of the National Energy Storage Mission was proposed in February 2018 and initiated to develop a comprehensive policy and regulatory framework. During the last 4 years, projects included in R&D worth INR 115.8 million (USD 1.66 million) in the domain of energy storage have been launched, and a corpus of INR 48.2 million (USD 0.7 million) has been issued. India’s energy storage mission will provide an opportunity for globally competitive battery manufacturing. By increasing the battery manufacturing expertise and scaling up its national production capacity, the country can make a substantial economic contribution in this crucial sector. The mission aims to identify the cumulative battery requirements, total market size, imports, and domestic manufacturing. Table 20 presents the economic opportunity from battery manufacturing given by the National Institution for Transforming India, also called NITI Aayog, which provides relevant technical advice to central and state governments while designing strategic and long-term policies and programs for the Indian government.

Small hydropower—3-year action agenda—2017

Hydro projects are classified as large hydro, small hydro (2 to 25 MW), micro-hydro (up to 100 kW), and mini-hydropower (100 kW to 2 MW) projects. Whereas the estimated potential of SHP is 20 GW, the 2022 target for India in SHP is 5 GW. As of the 31st of December 2018, the country has achieved 4.5 GW and this production is constantly increasing. The objective, which was planned to be accomplished through infrastructure project grants and tariff support, was included in the NITI Aayog’s 3-year action agenda (2017–2018 to 2019–2020), which was published on the 1st of August 2017. MNRE is providing central financial assistance (CFA) to set up small/micro hydro projects both in the public and private sector. For the identification of new potential locations, surveys and comprehensive project reports are elaborated, and financial support for the renovation and modernization of old projects is provided. The Ministry has established a dedicated completely automatic supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA)—based on a hydraulic turbine R&D laboratory at the Alternate Hydro Energy Center (AHEC) at IIT Roorkee. The establishment cost for the lab was INR 40 crore (400 million INR, 95.62 Million USD), and the laboratory will serve as a design and validation facility. It investigates hydro turbines and other hydro-mechanical devices adhering to national and international standards [ 54 , 55 ]. Table 21 shows the target and achievements from 2007–2008 to 2018–2019.

National policy regarding biofuels—2018

Modernization has generated an opportunity for a stable change in the use of bioenergy in India. MNRE amended the current policy for biomass in May 2018. The policy presents CFA for projects using biomass such as agriculture-based industrial residues, wood produced through energy plantations, bagasse, crop residues, wood waste generated from industrial operations, and weeds. Under the policy, CFA will be provided to the projects at the rate of INR 2.5 million (USD 35,477.7) per MW for bagasse cogeneration and INR 5 million (USD 70,955.5) per MW for non-bagasse cogeneration. The MNRE also announced a memorandum in November 2018 considering the continuation of the concessional customs duty certificate (CCDC) to set up projects for the production of energy using non-conventional materials such as bio-waste, agricultural, forestry, poultry litter, agro-industrial, industrial, municipal, and urban wastes. The government recently established the National policy on biofuels in August 2018. The MNRE invited an expression of interest (EOI) to estimate the potential of biomass energy and bagasse cogeneration in the country. A program to encourage the promotion of biomass-based cogeneration in sugar mills and other industries was also launched in May 2018. Table 22 shows how the biomass power target and achievements are expected to reach 10 GW of the target of 2022 before the end of 2019.

The new national biogas and organic manure program (NNBOMP)—2018

The National biogas and manure management programme (NBMMP) was launched in 2012–2013. The primary objective was to provide clean gaseous fuel for cooking, where the remaining slurry was organic bio-manure which is rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Further, 47.5 lakh (4.75 million) cumulative biogas plants were completed in 2014, and increased to 49.8 lakh (4.98 million). During 2017–2018, the target was to establish 1.10 lakh biogas plants (1.10 million), but resulted in 0.15 lakh (0.015 million). In this way, the cost of refilling the gas cylinders with liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) was greatly reduced. Likewise, tons of wood/trees were protected from being axed, as wood is traditionally used as a fuel in rural and semi-urban households. Biogas is a viable alternative to traditional cooking fuels. The scheme generated employment for almost 300 skilled laborers for setting up the biogas plants. By 30th of May 2018, the Ministry had issued guidelines for the implementation of the NNBOMP during the period 2017–2018 to 2019–2020 [ 56 ].

The off-grid and decentralized solar photovoltaic application program—2018

The program deals with the energy demand through the deployment of solar lanterns, solar streetlights, solar home lights, and solar pumps. The plan intended to reach 118 MWp of off-grid PV capacity by 2020. The sanctioning target proposed outlay was 50 MWp by 2017–2018 and 68 MWp by 2019–2020. The total estimated cost amounted to INR 1895 crore (18950 Million INR, 265.547 million USD), and the ministry wanted to support 637 crores (6370 million INR, 89.263 million USD) by its central finance assistance. Solar power plants with a 25 KWp size were promoted in those areas where grid power does not reach households or is not reliable. Public service institutions, schools, panchayats, hostels, as well as police stations will benefit from this scheme. Solar study lamps were also included as a component in the program. Thirty percent of financial assistance was provided to solar power plants. Every student should bear 15% of the lamp cost, and the ministry wanted to support the remaining 85%. As of October 2018, lantern and lamps of more than 40 Lakhs (4 million), home lights of 16.72 lakhs (1.672 million) number, street lights of 6.40 lakhs (0.64 million), solar pumps of 1.96 lakhs (0.196 million), and 187.99 MWp stand-alone devices had been installed [ 57 , 58 ].

Major government initiatives for renewable energy

Technological initiatives.

The Technology Development and Innovation Policy (TDIP) released on the 6th of October 2017 was endeavored to promote research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) in the renewable energy sector [ 59 ]. RD&D intended to evaluate resources, progress in technology, commercialization, and the presentation of renewable energy technologies across the country. It aimed to produce renewable power devices and systems domestically. The evaluation of standards and resources, processes, materials, components, products, services, and sub-systems was carried out through RD&D. A development of the market, efficiency improvements, cost reductions, and a promotion of commercialization (scalability and bankability) were achieved through RD&D. Likewise, the percentage of renewable energy in the total electricity mix made it self-sustainable, industrially competitive, and profitable through RD&D. RD&D also supported technology development and demonstration in wind, solar, wind-solar hybrid, biofuel, biogas, hydrogen fuel cells, and geothermal energies. RD&D supported the R&D units of educational institutions, industries, and non-government organizations (NGOs). Sharing expertise, information, as well as institutional mechanisms for collaboration was realized by use of the technology development program (TDP). The various people involved in this program were policymakers, industrial innovators, associated stakeholders and departments, researchers, and scientists. Renowned R&D centers in India are the National Institute of Solar Energy (NISE), Gurgaon, the National Institute of Bio-Energy (NIBE), Kapurthala, and the National Institute of Wind Energy (NIWE), Chennai. The TDP strategy encouraged the exploration of innovative approaches and possibilities to obtain long-term targets. Likewise, it efficiently supported the transformation of knowledge into technology through a well-established monitoring system for the development of renewable technology that meets the electricity needs of India. The research center of excellence approved the TDI projects, which were funded to strengthen R&D. Funds were provided for conducting training and workshops. The MNRE is now preparing a database of R&D accomplishments in the renewable energy sector.

The Impacting Research Innovation and Technology (IMPRINT) program seeks to develop engineering and technology (prototype/process development) on a national scale. IMPRINT is steered by the Indian Institute of Technologies (IITs) and Indian Institute of science (IISCs). The expansion covers all areas of engineering and technology including renewable technology. The ministry of human resource development (MHRD) finances up to 50% of the total cost of the project. The remaining costs of the project are financed by the ministry (MNRE) via the RD&D program for renewable projects. Currently (2018–2019), five projects are under implementation in the area of solar thermal systems, storage for SPV, biofuel, and hydrogen and fuel cells which are funded by the MNRE (36.9 million INR, 0.518426 Million USD) and IMPRINT. Development of domestic technology and quality control are promoted through lab policies that were published on the 7th of December 2017. Lab policies were implemented to test, standardize, and certify renewable energy products and projects. They supported the improvement of the reliability and quality of the projects. Furthermore, Indian test labs are strengthened in line with international standards and practices through well-established lab policies. From 2015, the MNRE has provided “The New and Renewable Energy Young Scientist’s Award” to researchers/scientists who demonstrate exceptional accomplishments in renewable R&D.

Financial initiatives

One hundred percent financial assistance is granted by the MNRE to the government and NGOs and 50% financial support to the industry. The policy framework was developed to guide the identification of the project, the formulation, monitoring appraisal, approval, and financing. Between 2012 and 2017, a 4467.8 million INR, 62.52 Million USD) support was granted by the MNRE. The MNRE wanted to double the budget for technology development efforts in renewable energy for the current three-year plan period. Table 23 shows that the government is spending more and more for the development of the renewable energy sector. Financial support was provided to R&D projects. Exceptional consideration was given to projects that worked under extreme and hazardous conditions. Furthermore, financial support was applied to organizing awareness programs, demonstrations, training, workshops, surveys, assessment studies, etc. Innovative approaches will be rewarded with cash prizes. The winners will be presented with a support mechanism for transforming their ideas and prototypes into marketable commodities such as start-ups for entrepreneur development. Innovative projects will be financed via start-up support mechanisms, which will include an investment contract with investors. The MNRE provides funds to proposals for investigating policies and performance analyses related to renewable energy.

Technology validation and demonstration projects and other innovative projects with regard to renewables received a financial assistance of 50% of the project cost. The CFA applied to partnerships with industry and private institutions including engineering colleges. Private academic institutions, accredited by a government accreditation body, were also eligible to receive a 50% support. The concerned industries and institutions should meet the remaining 50% expenditure. The MNRE allocated an INR 3762.50 crore (INR 37625 million, 528.634 million USD) for the grid interactive renewable sources and an INR 1036.50 crore (INR 10365 million, 145.629 million USD) for off-grid/distributed and decentralized renewable power for the year 2018–2019 [ 60 ]. The MNRE asked the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), attempting to build renewable power projects under “priority sector lending” (priority lending should be done for renewable energy projects and without any limit) and to eliminate the obstacles in the financing of renewable energy projects. In July 2018, the Ministry of Finance announced that it would impose a 25% safeguard duty on solar panels and modules imported from China and Malaysia for 1 year. The quantum of tax might be reduced to 20% for the next 6 months, and 15% for the following 6 months.

Policy and regulatory framework initiatives

The regulatory interventions for the development of renewable energy sources are (a) tariff determination, (b) defining RPO, (c) promoting grid connectivity, and (d) promoting the expansion of the market.

Tariff policy amendments—2018

On the 30th of May 2018, the MoP released draft amendments to the tariff policy. The objective of these policies was to promote electricity generation from renewables. MoP in consultation with MNRE announced the long-term trajectory for RPO, which is represented in Table 24 . The State Electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC) achieved a favorable and neutral/off-putting effect in the growth of the renewable power sector through their RPO regulations in consultation with the MNRE. On the 25th of May 2018, the MNRE created an RPO compliance cell to reach India’s solar and wind power goals. Due to the absence of implementation of RPO regulations, several states in India did not meet their specified RPO objectives. The cell will operate along with the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) and SERCs to obtain monthly statements on RPO compliance. It will also take up non-compliance associated concerns with the relevant officials.

Repowering policy—2016

On the 09th of August 2016, India announced a “repowering policy” for wind energy projects. An about 27 GW turnaround was possible according to the policy. This policy supports the replacing of aging wind turbines with more modern and powerful units (fewer, larger, taller) to raise the level of electricity generation. This policy seeks to create a simplified framework and to promote an optimized use of wind power resources. It is mandatory because the up to the year 2000 installed wind turbines were below 500 kW in sites where high wind potential might be achieved. It will be possible to obtain 3000 MW from the same location once replacements are in place. The policy was initially applied for the one MW installed capacity of wind turbines, and the MNRE will extend the repowering policy to other projects in the future based on experience. Repowering projects were implemented by the respective state nodal agencies/organizations that were involved in wind energy promotion in their states. The policy provided an exception from the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) for wind farms/turbines undergoing repowering because they could not fulfill the requirements according to the PPA during repowering. The repowering projects may avail accelerated depreciation (AD) benefit or generation-based incentive (GBI) due to the conditions appropriate to new wind energy projects [ 61 ].

The wind-solar hybrid policy—2018

On the 14th of May 2018, the MNRE announced a national wind-solar hybrid policy. This policy supported new projects (large grid-connected wind-solar photovoltaic hybrid systems) and the hybridization of the already available projects. These projects tried to achieve an optimal and efficient use of transmission infrastructure and land. Better grid stability was achieved and the variability in renewable power generation was reduced. The best part of the policy intervention was that which supported the hybridization of existing plants. The tariff-based transparent bidding process was included in the policy. Regulatory authorities should formulate the necessary standards and regulations for hybrid systems. The policy also highlighted a battery storage in hybrid projects for output optimization and variability reduction [ 62 ].

The national offshore wind energy policy—2015

The National Offshore Wind Policy was released in October 2015. On the 19th of June 2018, the MNRE announced a medium-term target of 5 GW by 2022 and a long-term target of 30 GW by 2030. The MNRE called expressions of Interest (EoI) for the first 1 GW of offshore wind (the last date was 08.06.2018). The EoI site is located in Pipavav port at the Gulf of Khambhat at a distance of 23 km facilitating offshore wind (FOWIND) where the consortium deployed light detection and ranging (LiDAR) in November 2017). Pipavav port is situated off the coast of Gujarat. The MNRE had planned to install more such equipment in the states of Tamil Nadu and Gujarat. On the 14 th of December 2018, the MNRE, through the National Institute of Wind Energy (NIWE), called tender for offshore environmental impact assessment studies at intended LIDAR points at the Gulf of Mannar, off the coast of Tamil Nadu for offshore wind measurement. The timeline for initiatives was to firstly add 500 MW by 2022, 2 to 2.5 GW by 2027, and eventually reaching 5 GW between 2028 and 2032. Even though the installation of large wind power turbines in open seas is a challenging task, the government has endeavored to promote this offshore sector. Offshore wind energy would add its contribution to the already existing renewable energy mix for India [ 63 ] .

The feed-in tariff policy—2018

On the 28th of January 2016, the revised tariff policy was notified following the Electricity Act. On the 30th May 2018, the amendment in tariff policy was released. The intentions of this tariff policy are (a) an inexpensive and competitive electricity rate for the consumers; (b) to attract investment and financial viability; (c) to ensure that the perceptions of regulatory risks decrease through predictability, consistency, and transparency of policy measures; (d) development in quality of supply, increased operational efficiency, and improved competition; (e) increase the production of electricity from wind, solar, biomass, and small hydro; (f) peaking reserves that are acceptable in quantity or consistently good in quality or performance of grid operation where variable renewable energy source integration is provided through the promotion of hydroelectric power generation, including pumped storage projects (PSP); (g) to achieve better consumer services through efficient and reliable electricity infrastructure; (h) to supply sufficient and uninterrupted electricity to every level of consumers; and (i) to create adequate capacity, reserves in the production, transmission, and distribution that is sufficient for the reliability of supply of power to customers [ 64 ].

Training and educational initiatives

The MHRD has developed strong renewable energy education and training systems. The National Council for Vocational Training (NCVT) develops course modules, and a Modular Employable Skilling program (MES) in its regular 2-year syllabus to include SPV lighting systems, solar thermal systems, SHP, and provides the certificate for seven trades after the completion of a 2-year course. The seven trades are plumber, fitter, carpenter, welder, machinist, and electrician. The Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE) worked out a national skill development policy in 2015. They provide regular training programs to create various job roles in renewable energy along with the MNRE support through a skill council for green jobs (SCGJ), the National Occupational Standards (NOS), and the Qualification Pack (QP). The SCGJ is promoted by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) and the MNRE. The industry partner for the SCGJ is ReNew Power [ 65 , 66 ].

The global status of India in renewable energy

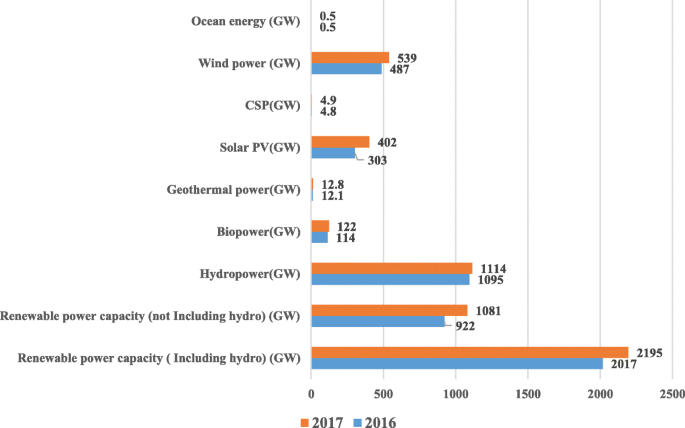

Table 25 shows the RECAI (Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index) report of 40 countries. This report is based on the attractiveness of renewable energy investment and deployment opportunities. RECAI is based on macro vitals such as economic stability, investment climate, energy imperatives such as security and supply, clean energy gap, and affordability. It also includes policy enablement such as political stability and support for renewables. Its emphasis lies on project delivery parameters such as energy market access, infrastructure, and distributed generation, finance, cost and availability, and transaction liquidity. Technology potentials such as natural resources, power take-off attractiveness, potential support, technology maturity, and forecast growth are taken into consideration for ranking. India has moved to the fourth position of the RECAI-2018. Indian solar installations (new large-scale and rooftop solar capacities) in the calendar year 2017 increased exponentially with the addition of 9629 MW, whereas in 2016 it was 4313 MW. The warning of solar import tariffs and conflicts between developers and distribution firms are growing investor concerns [ 67 ]. Figure 6 shows the details of the installed capacity of global renewable energy in 2016 and 2017. Globally, 2017 GW renewable energy was installed in 2016, and in 2017, it increased to 2195 GW. Table 26 shows the total capacity addition of top countries until 2017. The country ranked fifth in renewable power capacity (including hydro energy), renewable power capacity (not including hydro energy) in fourth position, concentrating solar thermal power (CSP) and wind power were also in fourth position [ 68 ].

Globally installed capacity of renewable energy in 2017—Global 2018 status report with regard to renewables [ 68 ]

The investment opportunities in renewable energy in India

The investments into renewable energy in India increased by 22% in the first half of 2018 compared to 2017, while the investments in China dropped by 15% during the same period, according to a statement by the Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), which is shown in Table 27 [ 69 , 70 ]. At this rate, India is expected to overtake China and become the most significant growth market for renewable energy by the end of 2020. The country is eyeing pole position for transformation in renewable energy by reaching 175 GW by 2020. To achieve this target, it is quickly ramping up investments in this sector. The country added more renewable capacity than conventional capacity in 2018 when compared to 2017. India hosted the ISA first official summit on the 11.03.2018 for 121 countries. This will provide a standard platform to work toward the ambitious targets for renewable energy. The summit will emphasize India’s dedication to meet global engagements in a time-bound method. The country is also constructing many sizeable solar power parks comparable to, but larger than, those in China. Half of the earth’s ten biggest solar parks under development are in India.

In 2014, the world largest solar park was the Topaz solar farm in California with a 550 MW facility. In 2015, another operator in California, Solar Star, edged its capacity up to 579 MW. By 2016, India’s Kamuthi Solar Power Project in Tamil Nadu was on top with 648 MW of capacity (set up by the Adani Green Energy, part of the Adani Group, in Tamil Nadu). As of February 2017, the Longyangxia Dam Solar Park in China was the new leader, with 850 MW of capacity [ 71 ]. Currently, there are 600 MW operating units and 1400 MW units under construction. The Shakti Sthala solar park was inaugurated on 01.03.2018 in Pavagada (Karnataka, India) which is expected to become the globe’s most significant solar park when it accomplishes its full potential of 2 GW. Another large solar park with 1.5 GW is scheduled to be built in the Kadappa region [ 72 ]. The progress in solar power is remarkable and demonstrates real clean energy development on the ground.

The Kurnool ultra-mega solar park generated 800 million units (MU) of energy in October 2018 and saved over 700,000 tons of CO 2 . Rainwater was harvested using a reservoir that helps in cleaning solar panels and supplying water. The country is making remarkable progress in solar energy. The Kamuthi solar farm is cleaned each day by a robotic system. As the Indian economy expands, electricity consumption is forecasted to reach 15,280 TWh in 2040. With the government’s intent, green energy objectives, i.e., the renewable sector, grow considerably in an attractive manner with both foreign and domestic investors. It is anticipated to attract investments of up to USD 80 billion in the subsequent 4 years. The government of India has raised its 175 GW target to 225 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2022. The competitive benefit is that the country has sun exposure possible throughout the year and has an enormous hydropower potential. India was also listed fourth in the EY renewable energy country attractive index 2018. Sixty solar cities will be built in India as a section of MNRE’s “Solar cities” program.

In a regular auction, reduction in tariffs cost of the projects are the competitive benefits in the country. India accounts for about 4% of the total global electricity generation capacity and has the fourth highest installed capacity of wind energy and the third highest installed capacity of CSP. The solar installation in India erected during 2015–2016, 2016–2017, 2017–2018, and 2018–2019 was 3.01 GW, 5.52 GW, 9.36 GW, and 6.53 GW, respectively. The country aims to add 8.5 GW during 2019–2020. Due to its advantageous location in the solar belt (400 South to 400 North), the country is one of the largest beneficiaries of solar energy with relatively ample availability. An increase in the installed capacity of solar power is anticipated to exceed the installed capacity of wind energy, approaching 100 GW by 2022 from its current levels of 25.21226 GW as of December 2018. Fast falling prices have made Solar PV the biggest market for new investments. Under the Union Budget 2018–2019, a zero import tax on parts used in manufacturing solar panels was launched to provide an advantage to domestic solar panel companies [ 73 ].

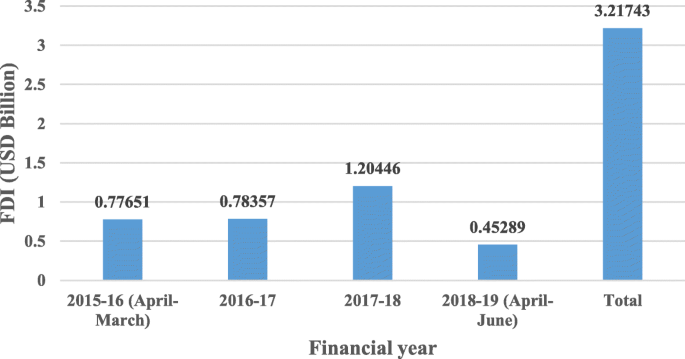

Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows in the renewable energy sector of India between April 2000 and June 2018 amounted to USD 6.84 billion according to the report of the department of industrial policy and promotion (DIPP). The DIPP was renamed (gazette notification 27.01.2019) the Department for the Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT). It is responsible for the development of domestic trade, retail trade, trader’s welfare including their employees as well as concerns associated with activities in facilitating and supporting business and startups. Since 2014, more than 42 billion USD have been invested in India’s renewable power sector. India reached US$ 7.4 billion in investments in the first half of 2018. Between April 2015 and June 2018, the country received USD 3.2 billion FDI in the renewable sector. The year-wise inflows expanded from USD 776 million in 2015–2016 to USD 783 million in 2016–2017 and USD 1204 million in 2017–2018. Between January to March of 2018, the INR 452 crore (4520 Million INR, 63.3389 million USD) of the FDI had already come in. The country is contributing with financial and promotional incentives that include a capital subsidy, accelerated depreciation (AD), waiver of inter-state transmission charges and losses, viability gap funding (VGF), and FDI up to 100% under the automated track.

The DIPP/DPIIT compiles and manages the data of the FDI equity inflow received in India [ 74 ]. The FDI equity inflow between April 2015 and June 2018 in the renewable sector is illustrated in Fig. 7 . It shows that the 2018–2019 3 months’ FDI equity inflow is half of that of the entire one of 2017–2018. It is evident from the figure that India has well-established FDI equity inflows. The significant FDI investments in the renewable energy sectors are shown in Table 28 . The collaboration between the Asian development bank and Renew Power Ventures private limited with 44.69 million USD ranked first followed by AIRRO Singapore with Diligent power with FDI equity inflow of 44.69 USD million.

The FDI equity inflow received between April 2015 and June 2018 in the renewable energy sector [ 73 ]

Strategies to promote investments

Strategies to promote investments (including FDI) by investors in the renewable sector:

Decrease constraints on FDI; provide open, transparent, and dependable conditions for foreign and domestic firms; and include ease of doing business, access to imports, comparatively flexible labor markets, and safeguard of intellectual property rights.

Establish an investment promotion agency (IPA) that targets suitable foreign investors and connects them as a catalyst with the domestic economy. Assist the IPA to present top-notch infrastructure and immediate access to skilled workers, technicians, engineers, and managers that might be needed to attract such investors. Furthermore, it should involve an after-investment care, recognizing the demonstration effects from satisfied investors, the potential for reinvestments, and the potential for cluster-development due to follow-up investments.

It is essential to consider the targeted sector (wind, solar, SPH or biomass, respectively) for which investments are required.

Establish the infrastructure needed for a quality investor, including adequate close-by transport facilities (airport, ports), a sufficient and steady supply of energy, a provision of a sufficiently skilled workforce, the facilities for the vocational training of specialized operators, ideally designed in collaboration with the investor.

Policy and other support mechanisms such as Power Purchase Agreements (PPA) play an influential role in underpinning returns and restricting uncertainties for project developers, indirectly supporting the availability of investment. Investors in renewable energy projects have historically relied on government policies to give them confidence about the costs necessary for electricity produced—and therefore for project revenues. Reassurance of future power costs for project developers is secured by signing a PPA with either a utility or an essential corporate buyer of electricity.

FiT have been the most conventional approach around the globe over the last decade to stimulate investments in renewable power projects. Set by the government concerned, they lay down an electricity tariff that developers of qualifying new projects might anticipate to receive for the resulting electricity over a long interval (15–20 years). These present investors in the tax equity of renewable power projects with a credit that they can manage to offset the tax burden outside in their businesses.

Table 29 presents the 2018 renewable energy investment report, source-wise, by the significant players in renewables according to the report of the Bloomberg New Energy Finance Report 2018. As per this report, global investment in renewable energy was USD of 279.8 billion in 2017. The top ten in the total global investments are China (126.1 $BN), the USA (40.5 $BN), Japan (13.4 $BN), India (10.9 $BN), Germany (10.4 $BN), Australia (8.5 $BN), UK (7.6 $BN), Brazil (6.0 $BN), Mexico (6.0 $BN), and Sweden (3.7 $BN) [ 75 ]. This achievement was possible since those countries have well-established strategies for promoting investments [ 76 , 77 ].

The appropriate objectives for renewable power expansion and investments are closely related to the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) objectives, the implementation of the NDC, on the road to achieving Paris promises, policy competence, policy reliability, market absorption capacity, and nationwide investment circumstances that are the real purposes for renewable power expansion, which is a significant factor for the investment strategies, as is shown in Table 30 .

The demand for investments for building a Paris-compatible and climate-resilient energy support remains high, particularly in emerging nations. Future investments in energy grids and energy flexibility are of particular significance. The strategies and the comparison chart between China, India, and the USA are presented in Table 31 .

Table 32 shows France in the first place due to overall favorable conditions for renewables, heading the G20 in investment attractiveness of renewables. Germany drops back one spot due to a decline in the quality of the global policy environment for renewables and some insufficiencies in the policy design, as does the UK. Overall, with four European countries on top of the list, Europe, however, directs the way in providing attractive conditions for investing in renewables. Despite high scores for various nations, no single government is yet close to growing a role model. All countries still have significant room for increasing investment demands to deploy renewables at the scale required to reach the Paris objectives. The table shown is based on the Paris compatible long-term vision, the policy environment for renewable energy, the conditions for system integration, the market absorption capacity, and general investment conditions. India moved from the 11th position to the 9th position in overall investments between 2017 and 2018.

A Paris compatible long-term vision includes a de-carbonization plan for the power system, the renewable power ambition, the coal and oil decrease, and the reliability of renewables policies. Direct support policies include medium-term certainty of policy signals, streamlined administrative procedures, ensuring project realization, facilitating the use of produced electricity. Conditions for system integration include system integration-grid codes, system integration-storage promotion, and demand-side management policies. A market absorption capacity includes a prior experience with renewable technologies, a current activity with renewable installations, and a presence of major renewable energy companies. General investment conditions include non-financial determinants, depth of the financial sector as well, as an inflation forecast.

Employment opportunities for citizens in renewable energy in India

Global employment scenario.

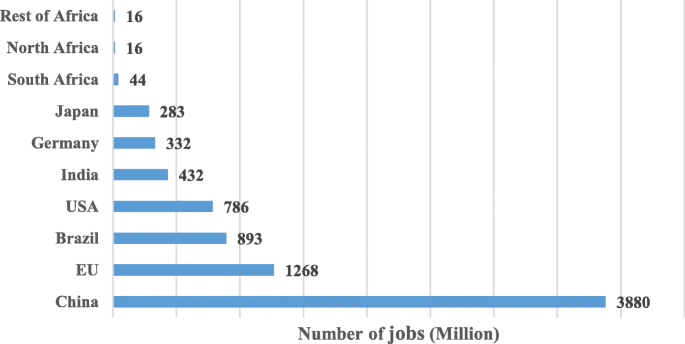

According to the 2018 Annual review of the IRENA [ 78 ], global renewable energy employment touched 10.3 million jobs in 2017, an improvement of 5.3% compared with the quantity published in 2016. Many socio-economic advantages derive from renewable power, but employment continues to be exceptionally centralized in a handful of countries, with China, Brazil, the USA, India, Germany, and Japan in the lead. In solar PV employment (3.4 million jobs), China is the leader (65% of PV Jobs) which is followed by Japan, USA, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Germany, Philippines, and Turkey. In biofuels employment (1.9 million jobs), Brazil is the leader (41% of PV Jobs) followed by the USA, Colombia, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, China, and India. In wind employment (1.1 million jobs), China is the leader (44% of PV Jobs) followed by Germany, USA, India, UK, Brazil, Denmark, Netherlands, France, and Spain.

Table 33 shows global renewable energy employment in the corresponding technology branches. As in past years, China maintained the most notable number of people employed (3880 million jobs) estimating for 43% of the globe’s total which is shown in Fig. 8 . In India, new solar installations touched a record of 9.6 GW in 2017, efficiently increasing the total installed capacity. The employment in solar PV improved by 36% and reached 164,400 jobs, of which 92,400 represented on-grid use. IRENA determines that the building and installation covered 46% of these jobs, with operations and maintenance (O&M) representing 35% and 19%, individually. India does not produce solar PV because it could be imported from China, which is inexpensive. The market share of domestic companies (Indian supplier to renewable projects) declined from 13% in 2014–2015 to 7% in 2017–2018. If India starts the manufacturing base, more citizens will get jobs in the manufacturing field. India had the world’s fifth most significant additions of 4.1 GW to wind capacity in 2017 and the fourth largest cumulative capacity in 2018. IRENA predicts that jobs in the wind sector stood at 60,500.

Renewable energy employment in selected countries [ 79 ]

The jobs in renewables are categorized into technological development, installation/de-installation, operation, and maintenance. Tables 34 , 35 , 36 , and 37 show the wind industry, solar energy, biomass, and small hydro-related jobs in project development, component manufacturing, construction, operations, and education, training, and research. As technology quickly evolves, workers in all areas need to update their skills through continuing training/education or job training, and in several cases could benefit from professional certification. The advantages of moving to renewable energy are evident, and for this reason, the governments are responding positively toward the transformation to clean energy. Renewable energy can be described as the country’s next employment boom. Renewable energy job opportunities can transform rural economy [ 79 , 80 ]. The renewable energy sector might help to reduce poverty by creating better employment. For example, wind power is looking for specialists in manufacturing, project development, and construction and turbine installation as well as financial services, transportation and logistics, and maintenance and operations.

The government is building more renewable energy power plants that will require a workforce. The increasing investments in the renewable energy sector have the potential to provide more jobs than any other fossil fuel industry. Local businesses and renewable sectors will benefit from this change, as income will increase significantly. Many jobs in this sector will contribute to fixed salaries, healthcare benefits, and skill-building opportunities for unskilled and semi-skilled workers. A range of skilled and unskilled jobs are included in all renewable energy technologies, even though most of the positions in the renewable energy industry demand a skilled workforce. The renewable sector employs semi-skilled and unskilled labor in the construction, operations, and maintenance after proper training. Unskilled labor is employed as truck drivers, guards, cleaning, and maintenance. Semi-skilled labor is used to take regular readings from displays. A lack of consistent data on the potential employment impact of renewables expansion makes it particularly hard to assess the quantity of skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled personnel that might be needed.

Key findings in renewable energy employment

The findings comprise (a) that the majority of employment in the renewable sector is contract based, and that employees do not benefit from permanent jobs or security. (b) Continuous work in the industry has the potential to decrease poverty. (c) Most poor citizens encounter obstacles to entry-level training and the employment market due to lack of awareness about the jobs and the requirements. (d) Few renewable programs incorporate developing ownership opportunities for the citizens and the incorporation of women in the sector. (e) The inadequacy of data makes it challenging to build relationships between employment in renewable energy and poverty mitigation.

Recommendations for renewable energy employment

When building the capacity, focus on poor people and individuals to empower them with training in operation and maintenance.

Develop and offer training programs for citizens with minimal education and training, who do not fit current programs, which restrict them from working in renewable areas.

Include women in the renewable workforce by providing localized training.

Establish connections between training institutes and renewable power companies to guarantee that (a) trained workers are placed in appropriate positions during and after the completion of the training program and (b) training programs match the requirements of the renewable sector.

Poverty impact assessments might be embedded in program design to know how programs motivate poverty reduction, whether and how they influence the community.

Allow people to have a sense of ownership in renewable projects because this could contribute to the growth of the sector.