An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Re-Examining the Evidence for School-Based Comprehensive Sex Education: A Global Research Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Senior Research Analyst, The Institute for Research & Evaluation, Salt Lake City, Utah, U.S.A.

- 2 Founder & Director, The Institute for Research & Evaluation, Salt Lake City, Utah, U.S.A.

- PMID: 33950605

Purpose: To evaluate the global research on school-based comprehensive sex education (CSE) by applying rigorous and meaningful criteria to outcomes of credible studies in order to identify evidence of real program effectiveness.

Methods: We examined 120 studies of school-based sex education contained in the reviews of research sponsored by three authoritative agencies: the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, the U.S. federal Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Their reviews screened more than 600 hundred studies and accepted only those that reached a threshold of adequate scientific rigor. These included 60 U.S. studies and 43 non-U.S. studies of school-based CSE plus 17 U.S. studies of school-based abstinence education (AE). We evaluated these studies for evidence of effectiveness using criteria grounded in the science of prevention research: sustained positive impact (at least 12 months post-program), on a key protective indicator (abstinence, condom use-especially consistent use, pregnancy, or STDs), for the main (targeted) teenage population, and without negative/harmful program effects.

Results: Worldwide, six out of 103 school-based CSE studies (U.S. and non-U.S. combined) showed main effects on a key protective indicator, sustained at least 12 months post-program, excluding programs that also had negative effects. Sixteen studies found harmful CSE impacts. Looking just at the U.S., of the 60 school-based CSE studies, three found sustained main effects on a key protective indicator (excluding programs with negative effects) and seven studies found harmful impact. For the 17 AE studies in the U.S., seven showed sustained protective main effects and one study showed harmful effects.

Conclusions: Some of the strongest, most current school-based CSE studies worldwide show very little evidence of real program effectiveness. In the U.S., the evidence, though limited, appeared somewhat better for abstinence education.

Keywords: Abstinence Education; Comprehensive Sex Education; Sex Education; Sex Education Effectiveness; Teenage Pregnancy.

Copyright © 2019 by the National Legal Center for the Medically Dependent and Disabled, Inc.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- The effectiveness of school-based family asthma educational programs on the quality of life and number of asthma exacerbations of children aged five to 18 years diagnosed with asthma: a systematic review protocol. Walter H, Sadeque-Iqbal F, Ulysse R, Castillo D, Fitzpatrick A, Singleton J. Walter H, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015 Oct;13(10):69-81. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2335. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015. PMID: 26571284

- The effectiveness of web-based programs on the reduction of childhood obesity in school-aged children: A systematic review. Antwi F, Fazylova N, Garcon MC, Lopez L, Rubiano R, Slyer JT. Antwi F, et al. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10(42 Suppl):1-14. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2012-248. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012. PMID: 27820152

- "Three Decades of Research:" A New Sex Ed Agenda and the Veneer of Science. Ericksen IH, Weed SE. Ericksen IH, et al. Issues Law Med. 2023 Spring;38(1):27-46. Issues Law Med. 2023. PMID: 37642452 Review.

- Abstinence-only programs for HIV infection prevention in high-income countries. Underhill K, Operario D, Montgomery P. Underhill K, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD005421. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005421.pub2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007. PMID: 17943855 Review.

- Abstinence promotion and the provision of information about contraception in public school district sexuality education policies. Landry DJ, Kaeser L, Richards CL. Landry DJ, et al. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999 Nov-Dec;31(6):280-6. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999. PMID: 10614518

- A reanalysis of the Institute for Research and Evaluation report that challenges non-US, school-based comprehensive sexuality education evidence base. VanTreeck K, Elnakib S, Chandra-Mouli V. VanTreeck K, et al. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2023 Dec;31(1):2237791. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2023.2237791. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2023. PMID: 37548507 Free PMC article. Review.

Related information

- Cited in Books

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Reasons to publish with us

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, purpose of the study, literature search and selection criteria, coding of the studies for exploration of moderators, decisions related to the computation of effect sizes.

- < Previous

The effectiveness of school-based sex education programs in the promotion of abstinent behavior: a meta-analysis

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Mónica Silva, The effectiveness of school-based sex education programs in the promotion of abstinent behavior: a meta-analysis, Health Education Research , Volume 17, Issue 4, August 2002, Pages 471–481, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/17.4.471

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This review presents the findings from controlled school-based sex education interventions published in the last 15 years in the US. The effects of the interventions in promoting abstinent behavior reported in 12 controlled studies were included in the meta-analysis. The results of the analysis indicated a very small overall effect of the interventions in abstinent behavior. Moderator analysis could only be pursued partially because of limited information in primary research studies. Parental participation in the program, age of the participants, virgin-status of the sample, grade level, percentage of females, scope of the implementation and year of publication of the study were associated with variations in effect sizes for abstinent behavior in univariate tests. However, only parental participation and percentage of females were significant in the weighted least-squares regression analysis. The richness of a meta-analytic approach appears limited by the quality of the primary research. Unfortunately, most of the research does not employ designs to provide conclusive evidence of program effects. Suggestions to address this limitation are provided.

Sexually active teenagers are a matter of serious concern. In the past decades many school-based programs have been designed for the sole purpose of delaying the initiation of sexual activity. There seems to be a growing consensus that schools can play an important role in providing youth with a knowledge base which may allow them to make informed decisions and help them shape a healthy lifestyle ( St Leger, 1999 ). The school is the only institution in regular contact with a sizable proportion of the teenage population ( Zabin and Hirsch, 1988 ), with virtually all youth attending it before they initiate sexual risk-taking behavior ( Kirby and Coyle, 1997 ).

Programs that promote abstinence have become particularly popular with school systems in the US ( Gilbert and Sawyer, 1994 ) and even with the federal government ( Sexual abstinence program has a $250 million price tag, 1997 ). These are referred to in the literature as abstinence-only or value-based programs ( Repucci and Herman, 1991 ). Other programs—designated in the literature as safer-sex, comprehensive, secular or abstinence-plus programs—additionally espouse the goal of increasing usage of effective contraception. Although abstinence-only and safer-sex programs differ in their underlying values and assumptions regarding the aims of sex education, both types of programs strive to foster decision-making and problem-solving skills in the belief that through adequate instruction adolescents will be better equipped to act responsibly in the heat of the moment ( Repucci and Herman, 1991 ). Nowadays most safer-sex programs encourage abstinence as a healthy lifestyle and many abstinence only programs have evolved into `abstinence-oriented' curricula that also include some information on contraception. For most programs currently implemented in the US, a delay in the initiation of sexual activity constitutes a positive and desirable outcome, since the likelihood of responsible sexual behavior increases with age ( Howard and Mitchell, 1993 ).

Even though abstinence is a valued outcome of school-based sex education programs, the effectiveness of such interventions in promoting abstinent behavior is still far from settled. Most of the articles published on the effectiveness of sex education programs follow the literary format of traditional narrative reviews ( Quinn, 1986 ; Kirby, 1989 , 1992 ; Visser and van Bilsen, 1994 ; Jacobs and Wolf, 1995 ; Kirby and Coyle, 1997 ). Two exceptions are the quantitative overviews by Frost and Forrest ( Frost and Forrest, 1995 ) and Franklin et al . ( Franklin et al ., 1997 ).

In the first review ( Frost and Forrest, 1995 ), the authors selected only five rigorously evaluated sex education programs and estimated their impact on delaying sexual initiation. They used non-standardized measures of effect sizes, calculated descriptive statistics to represent the overall effect of these programs and concluded that those selected programs delayed the initiation of sexual activity. In the second review, Franklin et al . conducted a meta-analysis of the published research of community-based and school-based adolescent pregnancy prevention programs and contrary to the conclusions forwarded by Frost and Forrest, these authors reported a non-significant effect of the programs on sexual activity ( Franklin et al ., 1997 ).

The discrepancy between these two quantitative reviews may result from the decision by Franklin et al . to include weak designs, which do not allow for reasonable causal inferences. However, given that recent evidence indicates that weaker designs yield higher estimates of intervention effects ( Guyatt et al ., 2000 ), the inclusion of weak designs should have translated into higher effects for the Franklin et al . review and not smaller. Given the discrepant results forwarded in these two recent quantitative reviews, there is a need to clarify the extent of the impact of school-based sex education in abstinent behavior and explore the specific features of the interventions that are associated to variability in effect sizes.

The present study consisted of a meta-analytic review of the research literature on the effectiveness of school-based sex education programs in the promotion of abstinent behavior implemented in the past 15 years in the US in the wake of the AIDS epidemic. The goals were to: (1) synthesize the effects of controlled school-based sex education interventions on abstinent behavior, (2) examine the variability in effects among studies and (3) explain the variability in effects between studies in terms of selected moderator variables.

The first step was to locate as many studies conducted in the US as possible that dealt with the evaluation of sex education programs and which measured abstinent behavior subsequent to an intervention.

The primary sources for locating studies were four reference database systems: ERIC, PsychLIT, MEDLINE and the Social Science Citation Index. Branching from the bibliographies and reference lists in articles located through the original search provided another source for locating studies.

The process for the selection of studies was guided by four criteria, some of which have been employed by other authors as a way to orient and confine the search to the relevant literature ( Kirby et al ., 1994 ). The criteria to define eligibility of studies were the following.

Interventions had to be geared to normal adolescent populations attending public or private schools in the US and report on some measure of abstinent behavior: delay in the onset of intercourse, reduction in the frequency of intercourse or reduction in the number of sexual partners. Studies that reported on interventions designed for cognitively handicapped, delinquent, school dropouts, emotionally disturbed or institutionalized adolescents were excluded from the present review since they address a different population with different needs and characteristics. Community interventions which recruited participants from clinical or out-of-school populations were also eliminated for the same reasons.

Studies had to be either experimental or quasi-experimental in nature, excluding three designs that do not permit strong tests of causal hypothesis: the one group post-test-only design, the post-test-only design with non-equivalent groups and the one group pre-test–post-test design ( Cook and Campbell, 1979 ). The presence of an independent and comparable `no intervention' control group—in demographic variables and measures of sexual activity in the baseline—was required for a study to be included in this review.

Studies had to be published between January 1985 and July 2000. A time period restriction was imposed because of cultural changes that occur in society—such as the AIDS epidemic—which might significantly impact the adolescent cohort and alter patterns of behavior and consequently the effects of sex education interventions.

Five pairs of publications were detected which may have used the same database (or two databases which were likely to contain non-independent cases) ( Levy et al ., 1995 / Weeks et al ., 1995 ; Barth et al ., 1992 / Kirby et al ., 1991 /Christoper and Roosa, 1990/ Roosa and Christopher, 1990 and Jorgensen, 1991 / Jorgensen et al ., 1993 ). Only one effect size from each pair of articles was included to avoid the possibility of data dependence.

The exploration of study characteristics or features that may be related to variations in the magnitude of effect sizes across studies is referred to as moderator analysis. A moderator variable is one that informs about the circumstances under which the magnitude of effect sizes vary ( Miller and Pollock, 1994 ). The information retrieved from the articles for its potential inclusion as moderators in the data analysis was categorized in two domains: demographic characteristics of the participants in the sex education interventions and characteristics of the program.

Demographic characteristics included the following variables: the percentages of females, the percentage of whites, the virginity status of participants, mean (or median) age and a categorization of the predominant socioeconomic status of participating subjects (low or middle class) as reported by the authors of the primary study.

In terms of the characteristics of the programs, the features coded were: the type of program (whether the intervention was comprehensive/safer-sex or abstinence-oriented), the type of monitor who delivered the intervention (teacher/adult monitor or peer), the length of the program in hours, the scope of the implementation (large-scale versus small-scale trial), the time elapsed between the intervention and the post-intervention outcome measure (expressed as number of days), and whether parental participation (beyond consent) was a component of the intervention.

The type of sex education intervention was defined as abstinence-oriented if the explicit aim was to encourage abstinence as the primary method of protection against sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy, either totally excluding units on contraceptive methods or, if including contraception, portraying it as a less effective method than abstinence. An intervention was defined as comprehensive or safer-sex if it included a strong component on the benefits of use of contraceptives as a legitimate alternative method to abstinence for avoiding pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases.

A study was considered to be a large-scale trial if the intervention group consisted of more than 500 students.

Finally, year of publication was also analyzed to assess whether changes in the effectiveness of programs across time had occurred.

The decision to record information on all the above-mentioned variables for their potential role as moderators of effect sizes was based in part on theoretical considerations and in part on the empirical evidence of the relevance of such variables in explaining the effectiveness of educational interventions. A limitation to the coding of these and of other potentially relevant and interesting moderator variables was the scantiness of information provided by the authors of primary research. Not all studies described the features of interest for this meta-analysis. For parental participation, no missing values were present because a decision was made to code all interventions which did not specifically report that parents had participated—either through parent–youth sessions or homework assignments—as non-participation. However, for the rest of the variables, no similar assumptions seemed appropriate, and therefore if no pertinent data were reported for a given variable, it was coded as missing (see Table I ).

Once the pool of studies which met the inclusion criteria was located, studies were examined in an attempt to retrieve the size of the effect associated with each intervention. Since most of the studies did not report any effect size, it had to be estimated based on the significance level and inferential statistics with formulae provided by Rosenthal ( Rosenthal, 1991 ) and Holmes ( Holmes; 1984 ). When provided, the exact value for the test statistic or the exact probability was used in the calculation of the effect size.

Alternative methods to deal with non-independent effect sizes were not employed since these are more complex and require estimates of the covariance structure among the correlated effect sizes. According to Matt and Cook such estimates may be difficult—if not impossible—to obtain due to missing information in primary studies ( Matt and Cook, 1994 ).

Analyses of the effect sizes were conducted utilizing the D-STAT software ( Johnson, 1989 ). The sample sizes used for the overall effect size analysis corresponded to the actual number used to estimate the effects of interest, which was often less than the total sample of the study. Occasionally the actual sample sizes were not provided by the authors of primary research, but could be estimated from the degrees of freedom reported for the statistical tests.

The effect sizes were calculated from means and pooled standard deviations, t -tests, χ 2 , significance levels or from proportions, depending on the nature of the information reported by the authors of primary research. As recommended by Rosenthal, if results were reported simply as being `non-significant' a conservative estimate of the effect size was included, assuming P = 0.50, which corresponds to an effect size of zero ( Rosenthal, 1991 ). The overall measure of effect size reported was the corrected d statistic ( Hedges and Olkin, 1985 ). These authors recommend this measure since it does not overestimate the population effect size, especially in the case when sample sizes are small.

The homogeneity of effect sizes was examined to determine whether the studies shared a common effect size. Testing for homogeneity required the calculation of a homogeneity statistic, Q . If all studies share the same population effect size, Q follows an asymptotic χ 2 distribution with k – 1 degrees of freedom, where k is the number of effect sizes. For the purposes of this review the probability level chosen for significance testing was 0.10, due to the fact that the relatively small number of effect sizes available for the analysis limits the power to detect actual departures from homogeneity. Rejection of the hypothesis of homogeneity signals that the group of effect sizes is more variable than one would expect based on sampling variation and that one or more moderator variables may be present ( Hall et al ., 1994 ).

To examine the relationship between the study characteristics included as potential moderators and the magnitude of effect sizes, both categorical and continuous univariate tests were run. Categorical tests assess differences in effect sizes between subgroups established by dividing studies into classes based on study characteristics. Hedges and Olkin presented an extension of the Q statistic to test for homogeneity of effect sizes between classes ( Q B ) and within classes ( Q W ) ( Hedges and Olkin, 1985 ). The relationship between the effect sizes and continuous predictors was assessed using a procedure described by Rosenthal and Rubin which tests for linearity between effect sizes and predictors ( Rosenthal and Rubin, 1982 ).

Q E provides the test for model specification, when the number of studies is larger than the number of predictors. Under those conditions, Q E follows an approximate χ 2 distribution with k – p – 1 degrees of freedom, where k is the number of effect sizes and p is the number of regressors ( Hedges and Olkin, 1985 ).

The search for school-based sex education interventions resulted in 12 research studies that complied with the criteria to be included in the review and for which effect sizes could be estimated.

The overall effect size ( d +) estimated from these studies was 0.05 and the 95% confidence interval about the mean included a lower bound of 0.01 to a high bound of 0.09, indicating a very minimal overall effect size. Table II presents the effect size of each study ( d i ) along with its 95% confidence interval and the overall estimate of the effect size. Homogeneity testing indicated the presence of variability among effect sizes ( Q (11) = 35.56; P = 0.000).

An assessment of interaction effects among significant moderators could not be explored since it would have required partitioning of the studies according to a first variable and testing of the second within the partitioned categories. The limited number of effect sizes precluded such analysis.

Parental participation appeared to moderate the effects of sex education on abstinence as indicated by the significant Q test between groups ( Q B(1) = 5.06; P = 0.025), as shown in Table III . Although small in magnitude ( d = 0.24), the point estimate for the mean weighted effect size associated with programs with parental participation appears substantially larger than the mean associated with those where parents did not participate ( d = 0.04). The confidence interval for parent participation does not include zero, thus indicating a small but positive effect. Controlling for parental participation appears to translate into homogeneous classes of effect sizes for programs that include parents, but not for those where parents did not participate ( Q W(9) = 28.94; P = 0.001) meaning that the effect sizes were not homogeneous within this class.

Virginity status of the sample was also a significant predictor of the variability among effect sizes ( Q B(1) = 3.47 ; P = 0.06). The average effect size calculated for virgins-only was larger than the one calculated for virgins and non-virgins ( d = 0.09 and d = 0.01, respectively). Controlling for virginity status translated into homogeneous classes for virgins and non-virgins although not for the virgins-only class ( Q W(5) = 27.09; P = 0.000).

The scope of the implementation also appeared to moderate the effects of the interventions on abstinent behavior. The average effect size calculated for small-scale intervention was significantly higher than that for large-scale interventions ( d = 0.26 and d = 0.01, respectively). The effects corresponding to the large-scale category were homogeneous but this was not the case for the small-scale class, where heterogeneity was detected ( Q W(4) = 14.71; P = 0.01)

For all three significant categorical predictors, deletion of one outlier ( Howard and McCabe, 1990 ) resulted in homogeneity among the effect sizes within classes.

Univariate tests of continuous predictors showed significant results in the case of percentage of females in the sample ( z = 2.11; P = 0.04), age of participants ( z = –1.67; P = 0.09), grade ( z = –1.80; P = 0.07) and year of publication ( z = –2.76; P = 0.006).

All significant predictors in the univariate analysis—with the exception of grade which had a very high correlation with age ( r = 0.97; P = 0.000)—were entered into a weighted least-squares regression analysis. In general, the remaining set of predictors had a moderate degree of intercorrelation, although none of the coefficients were statistically significant.

In the weighted least-squares regression analysis, only parental participation and the percentage of females in the study were significant. The two-predictor model explained 28% of the variance in effect sizes. The test of model specification yielded a significant Q E statistic suggesting that the two-predictor model cannot be regarded as correctly specified (see Table IV ).

This review synthesized the findings from controlled sex education interventions reporting on abstinent behavior. The overall mean effect size for abstinent behavior was very small, close to zero. No significant effect was associated to the type of intervention: whether the program was abstinence-oriented or comprehensive—the source of a major controversy in sex education—was not found to be associated to abstinent behavior. Only two moderators—parental participation and percentage of females—appeared to be significant in both univariate tests and the multivariable model.

Although parental participation in interventions appeared to be associated with higher effect sizes in abstinent behavior, the link should be explored further since it is based on a very small number of studies. To date, too few studies have reported success in involving parents in sex education programs. Furthermore, the primary articles reported very limited information about the characteristics of the parents who took part in the programs. Parents who were willing to participate might differ in important demographic or lifestyle characteristics from those who did not participate. For instance, it is possible that the studies that reported success in achieving parental involvement may have been dealing with a larger percentage of intact families or with parents that espoused conservative sexual values. Therefore, at this point it is not possible to affirm that parental participation per se exerts a direct influence in the outcomes of sex education programs, although clearly this is a variable that merits further study.

Interventions appeared to be more effective when geared to groups composed of younger students, predominantly females and those who had not yet initiated sexual activity. The association between gender and effect sizes—which appeared significant both in the univariate and multivariable analyses—should be explored to understand why females seem to be more receptive to the abstinence messages of sex education interventions.

Smaller-scale interventions appeared to be more effective than large-scale programs. The larger effects associated to small-scale trials seems worth exploring. It may be the case that in large-scale studies it becomes harder to control for confounding variables that may have an adverse impact on the outcomes. For example, large-scale studies often require external agencies or contractors to deliver the program and the quality of the delivery of the contents may turn out to be less than optimal ( Cagampang et al ., 1997 ).

Interestingly there was a significant change in effect sizes across time, with effect sizes appearing to wane across the years. It is not likely that this represents a decline in the quality of sex education interventions. A possible explanation for this trend may be the expansion of mandatory sex education in the US which makes it increasingly difficult to find comparison groups that are relatively unexposed to sex education. Another possible line of explanation refers to changes in cultural mores regarding sexuality that may have occurred in the past decades—characterized by an increasing acceptance of premarital sexual intercourse, a proliferation of sexualized messages from the media and increasing opportunities for sexual contact in adolescence—which may be eroding the attainment of the goal of abstinence sought by educational interventions.

In terms of the design and implementation of sex education interventions, it is worth noting that the length of the programs was unrelated to the magnitude in effect sizes for the range of 4.5–30 h represented in these studies. Program length—which has been singled out as a potential explanation for the absence of significant behavioral effects in a large-scale evaluation of a sex education program ( Kirby et al ., 1997a )—does not appear to be consistently associated with abstinent behavior. The impact of lengthening currently existing programs should be evaluated in future studies.

As it has been stated, the exploration of moderator variables could be performed only partially due to lack of information on the primary research literature. This has been a problem too for other reviewers in the field ( Franklin et al ., 1997 ). The authors of primary research did not appear to control for nor report on the potentially confounding influence of numerous variables that have been indicated in the literature as influencing sexual decision making or being associated with the initiation of sexual activity in adolescence such as academic performance, career orientation, religious affiliation, romantic involvement, number of friends who are currently having sex, peer norms about sexual activity and drinking habits, among others ( Herold and Goodwin, 1981 ; Christopher and Cate, 1984 ; Billy and Udry, 1985 ; Roche, 1986 ; Coker et al ., 1994 ; Kinsman et al ., 1998 ; Holder et al ., 2000 ; Thomas et al ., 2000 ). Even though randomization should take care of differences in these and other potentially confounding variables, given that studies can rarely assign students to conditions and instead assign classrooms or schools to conditions, it is advisable that more information on baseline characteristics of the sample be utilized to establish and substantiate the equivalence between the intervention and control groups in relevant demographic and lifestyle characteristics.

In terms of the communication of research findings, the richness of a meta-analytic approach will always be limited by the quality of the primary research. Unfortunately, most of the research in the area of sex education do not employ experimental or quasi-experimental designs and thus fall short of providing conclusive evidence of program effects. The limitations in the quality of research in sex education have been highlighted by several authors in the past two decades ( Kirby and Baxter, 1981 ; Card and Reagan, 1989 ; Kirby, 1989 ; Peersman et al ., 1996 ). Due to these deficits in the quality of research—which resulted in a reduced number of studies that met the criteria for inclusion and the limitations that ensued for conducting a thorough analysis of moderators—the findings of the present synthesis have to be considered merely tentative. Substantial variability in effect sizes remained unexplained by the present synthesis, indicating the need to include more information on a variety of potential moderating conditions that might affect the outcomes of sex education interventions.

Finally, although it is rarely the case that a meta-analysis will constitute an endpoint or final step in the investigation of a research topic, by indicating the weaknesses as well as the strengths of the existing research a meta-analysis can be a helpful aid for channeling future primary research in a direction that might improve the quality of empirical evidence and expand the theoretical understanding in a given field ( Eagly and Wood, 1994 ). Research in sex education could be greatly improved if more efforts were directed to test interventions utilizing randomized controlled trials, measuring intervening variables and by a more careful and detailed reporting of the results. Unless efforts are made to improve on the quality of the research that is being conducted, decisions about future interventions will continue to be based on a common sense and intuitive approach as to `what might work' rather than on solid empirical evidence.

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

Description of moderator variables

| Categorical predictor . | Continuous predictors . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Valid . | . | Valid . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . |

| Socioeconomic status | 8 | percent of females | 11 | 54 | 5 | 40 | 66 |

| low | 5 | ||||||

| middle | 3 | ||||||

| Type of program | 12 | percent of whites | 12 | 39 | 33 | 1 | 93 |

| comprehensive | 8 | ||||||

| abstinence-oriented | 4 | ||||||

| Type of monitor | 11 | age | 8 | 14 | 1.5 | 12 | 16 |

| teacher/adult | 9 | ||||||

| peer | 2 | ||||||

| Virginity status | 12 | length of the program | 12 | 10 | 7.4 | 4.5 | 30 |

| virgins-only | 6 | ||||||

| all (virgins + non-virgins) | 6 | ||||||

| Parental participation | 12 | timing of post-test | 10 | 221 | 218 | 1 | 540 |

| yes | 2 | ||||||

| no | 10 | ||||||

| Scope of the implementation | 12 | ||||||

| large scale | 7 | ||||||

| small scale | 5 | ||||||

| Categorical predictor . | Continuous predictors . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Valid . | . | Valid . | Mean . | SD . | Min . | Max . |

| Socioeconomic status | 8 | percent of females | 11 | 54 | 5 | 40 | 66 |

| low | 5 | ||||||

| middle | 3 | ||||||

| Type of program | 12 | percent of whites | 12 | 39 | 33 | 1 | 93 |

| comprehensive | 8 | ||||||

| abstinence-oriented | 4 | ||||||

| Type of monitor | 11 | age | 8 | 14 | 1.5 | 12 | 16 |

| teacher/adult | 9 | ||||||

| peer | 2 | ||||||

| Virginity status | 12 | length of the program | 12 | 10 | 7.4 | 4.5 | 30 |

| virgins-only | 6 | ||||||

| all (virgins + non-virgins) | 6 | ||||||

| Parental participation | 12 | timing of post-test | 10 | 221 | 218 | 1 | 540 |

| yes | 2 | ||||||

| no | 10 | ||||||

| Scope of the implementation | 12 | ||||||

| large scale | 7 | ||||||

| small scale | 5 | ||||||

Effect sizes of studies

| Study . | Effect size ( ) . | 95% CI for . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Lower . | Upper . |

| Brown .(1991) | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.11 |

| Denny .(1999) | 0.00 | −0.13 | 0.13 |

| Howard and McCabe (1990) | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.82 |

| Jorgensen (1991) | 0.49 | 0.07 | 0.91 |

| Kirby .(1991) | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.38 |

| Kirby .(1997a) | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.14 |

| Kirby .(1997b) | 0.0 | −0.10 | 0.10 |

| Main .(1994) | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| O'Donnell . (1999) | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| Roosa and Christopher (1990) | 0.00 | −0.23 | 0.23 |

| Walter and Vaughan (1993) | −0.05 | −0.21 | 0.11 |

| Weeks .(1995) | 0.00 | −0.09 | 0.09 |

| Overall effect size ( +) | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Study . | Effect size ( ) . | 95% CI for . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Lower . | Upper . |

| Brown .(1991) | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.11 |

| Denny .(1999) | 0.00 | −0.13 | 0.13 |

| Howard and McCabe (1990) | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.82 |

| Jorgensen (1991) | 0.49 | 0.07 | 0.91 |

| Kirby .(1991) | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.38 |

| Kirby .(1997a) | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.14 |

| Kirby .(1997b) | 0.0 | −0.10 | 0.10 |

| Main .(1994) | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| O'Donnell . (1999) | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| Roosa and Christopher (1990) | 0.00 | −0.23 | 0.23 |

| Walter and Vaughan (1993) | −0.05 | −0.21 | 0.11 |

| Weeks .(1995) | 0.00 | −0.09 | 0.09 |

| Overall effect size ( +) | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

Tests of categorical moderators for abstinence

| Variable and class . | Between-classes effect ( ) . | . | Mean weighted effect size . | 95% CI for . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | Lower . | Upper . | Homogeneity within each class ( ) . |

| < 0.10; < 0.05 ; < 0.01 | ||||||

| Significance indicates rejection of hypothesis of homogeneity. | ||||||

| Parent participation | 5.06 | |||||

| yes | 2 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 1.6 | |

| no | 10 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 28.9 | |

| Virginity status | 3.47* | |||||

| virgins-only | 6 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 27.09 | |

| all | 6 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 5.03 | |

| Scope of implementation | 19.16 | |||||

| Small scale | 5 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 14.71 | |

| Large scale | 7 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 1.73 | |

| Variable and class . | Between-classes effect ( ) . | . | Mean weighted effect size . | 95% CI for . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | . | . | Lower . | Upper . | Homogeneity within each class ( ) . |

| < 0.10; < 0.05 ; < 0.01 | ||||||

| Significance indicates rejection of hypothesis of homogeneity. | ||||||

| Parent participation | 5.06 | |||||

| yes | 2 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 1.6 | |

| no | 10 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 28.9 | |

| Virginity status | 3.47* | |||||

| virgins-only | 6 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 27.09 | |

| all | 6 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 5.03 | |

| Scope of implementation | 19.16 | |||||

| Small scale | 5 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 14.71 | |

| Large scale | 7 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 1.73 | |

Weighted least-squares regression and test of model specification

| Predictor . | . | SE . |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.10; < 0.05; < 0.01. | ||

| Parent participation: `yes' coded as 1; `no' coded 0. | ||

| Significance signals incorrect model specification. | ||

| Parent participation | 0.22 | 0.09 |

| Percent females | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Constant | −0.89 | 0.47 |

| 0.28 | ||

| 18.8 | ||

| Predictor . | . | SE . |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.10; < 0.05; < 0.01. | ||

| Parent participation: `yes' coded as 1; `no' coded 0. | ||

| Significance signals incorrect model specification. | ||

| Parent participation | 0.22 | 0.09 |

| Percent females | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Constant | −0.89 | 0.47 |

| 0.28 | ||

| 18.8 | ||

Barth, R., Fetro, J., Leland, N. and Volkan, K. ( 1992 ) Preventing adolescent pregnancy with social and cognitive skills. Journal of Adolescent Research , 7 , 208 –232.

Billy, J. and Udry, R. ( 1985 ) Patterns of adolescent friendship and effects on sexual behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly , 48 , 27 –41.

Brown, L., Barone, V., Fritz, G., Cebollero, P. and Nassau, J. ( 1991 ) AIDS education: the Rhode Island experience. Health Education Quarterly , 18 , 195 –206.*

Cagampang, H., Barth, R., Korpi, M. and Kirby, D. ( 1997 ) Education Now And Babies Later (ENABL): life history of a campaign to postpone sexual involvement. Family Planning Perspectives , 29 , 109 –114.

Card, J. and Reagan, R. ( 1989 ) Strategies for evaluating adolescent pregnancy programs. Family Planning Perspectives , 21 , 210 –220.

Christopher, F. and Roosa, M. ( 1990 ) An evaluation of an adolescent pregnancy prevention program: is `just say no' enough? Family relations , 39 , 68 –72.

Christopher, S. and Cate, R. ( 1984 ). Factors involved in premarital sexual decision-making. Journal of Sex Research , 20 , 363 –376.

Coker, A., Richter, D., Valois, R., McKeown, R., Garrison, C. and Vincent, M. ( 1994 ) Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. Journal of School Health , 64 , 372 –377.

Cook, T. and Campbell, D. (1979) Quasi-experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings . Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

Denny, G., Young, M. and Spear, C. ( 1999 ) An evaluation of the Sex Can Wait abstinence education curriculum series. American Journal of Health Behavior , 23 , 134 –143.*

Dunkin, M. ( 1996 ) Types of errors in synthesizing research in education. Review of Educational Research , 66 , 87 –97.

Eagly, A. and Wood, W. (1994) Using research synthesis to plan future research. In Cooper, H. and Hedges, L. (eds), The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 485–500.

Franklin, C., Grant, D., Corcoran, J., Miller, P. and Bultman, L. ( 1997 ) Effectiveness of prevention programs for adolescent pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family , 59 , 551 –567.

Frost, J. and Forrest, J. ( 1995 ) Understanding the impact of effective teenage pregnancy prevention programs. Family Planning Perspectives , 27 , 188 –195.

Gilbert, G. and Sawyer, R. (1994) Health Education: Creating Strategies for School and Community Health. Jones & Bartlett, Boston, MA.

Guyatt, G., Di Censo, A., Farewell, V., Willan, A. and Griffith, L. ( 2000 ) Randomized trials versus observational studies in adolescent pregnancy prevention. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology , 53 , 167 –174.

Hall, J., Rosenthal, R., Tickle-Deignen, L. and Mosteller, F. (1994) Hypotheses and problems in research synthesis. In Cooper, H. and Hedges, L. (eds), The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 457–483.

Hedges, L. and Olkin, I. (1985) Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

Herold, E. and Goodwin, S. ( 1981 ) Adamant virgins, potential non-virgins and non-virgins. Journal of Sex Research , 17 , 97 –113.

Holder, D., Durant, R., Harris, T., Daniel, J., Obeidallah, D. and Goodman, E. ( 2000 ) The association between adolescent spirituality and voluntary sexual activity. Journal of Adolescent Health , 26 , 295 –302.

Holmes, C. ( 1984 ) Effect size estimation in meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Education , 52 , 106 –109.

Howard, M. and McCabe, J. ( 1990 ) Helping teenagers postpone sexual involvement. Family Planning Perspectives , 22 , 21 –26.*

Howard, M. and Mitchell, M. ( 1993 ) Preventing teenage pregnancy: some questions to be answered and some answers to be questioned. Pediatric Annals , 22 , 109 –118.

Hunter, J. ( 1997 ) Needed: a ban on the significance test. Psychological Science , 8 , 3 –7.

Jacobs, C. and Wolf, E. ( 1995 ) School sexuality education and adolescent risk-taking behavior. Journal of School Health , 65 , 91 –95.

Johnson, B. (1989) DSTAT: Software for the Meta-Analytic Review of Research Literatures . Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

Jorgensen, S. ( 1991 ) Project taking-charge: An evaluation of an adolescent pregnancy prevention program. Family Relations , 40 , 373 –380.*

Jorgensen, S, Potts, V. and Camp, B. ( 1993 ) Project Taking Charge: six month follow-up of a pregnancy prevention program for early adolescents. Family Relations , 42 , 401 –406

Kinsman, S., Romer, D., Furstenberg, F. and Schwarz, D. ( 1998 ) Early sexual initiation: the role of peer norms. Pediatrics , 102 , 1185 –1192.

Kirby, D. ( 1989 ) Research on effectiveness of sex education programs. Theory and Practice , 28 , 165 –171.

Kirby, D. ( 1992 ) School-based programs to reduce sexual risk-taking behaviors. Journal of School Health , 62 , 280 –287.

Kirby, D. and Baxter, S. ( 1981 ) Evaluating sexuality education programs. Independent School , 41 , 105 –114.

Kirby, D. and Coyle, K. ( 1997 ) School-based programs to reduce sexual risk-taking behavior. Children and Youth Services Review , 19 , 415 –436.

Kirby, D., Barth, R., Leland, N. and Fetro, J. ( 1991 ) Reducing the risk: impact of a new curriculum on sexual risk-taking. Family Planning Perspectives , 23 , 253 –263.*

Kirby, D., Short, L., Collins, J., Rugg, D., Kolbe, L., Howard, M., Miller, B., Sonenstein, F. and Zabin, L. ( 1994 ) School-based programs to reduce sexual-risk behaviors: a review of effectiveness. Public Health Reports , 109 , 339 –360.

Kirby, D., Korpi, M., Barth, R. and Cagampang, H. ( 1997 ) The impact of Postponing Sexual Involvement curriculum among youths in California. Family Planning Perspectives , 29 , 100 –108.*

Kirby, D., Korpi, M., Adivi, C. and Weissman, J. ( 1997 ) An impact evaluation of Project Snapp: an AIDS and pregnancy prevention middle school program. AIDS Education and Prevention , 9 (A), 44 –61.*

Levy, S., Perhats, C., Weeks, K., Handler, S., Zhu, C. and Flay, B. ( 1995 ) Impact of a school-based AIDS prevention program on risk and protective behavior for newly sexually active students. Journal of School Health , 65 , 145 –151.

Main, D., Iverson, D., McGloin, J., Banspach, S., Collins, J., Rugg, D. and Kolbe, L. ( 1994 ) Preventing HIV infection among adolescents: evaluation of a school-based education program. Preventive Medicine , 23 , 409 –417.*

Matt, G. and Cook, T. (1994) Threats to the validity of research synthesis. In Cooper, H. and Hedges, L. (eds), The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 503–520.

Miller, N. and Pollock, V. (1994) Meta-analytic synthesis for theory development. In Cooper, H. and Hedges, L. (eds), The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp. 457–483.

O'Donnell, L., Stueve, A., Sandoval, A., Duran, R., Haber, D., Atnafou, R., Johnson, N., Grant, U., Murray, H., Juhn, G., Tang, J. and Piessens, P. ( 1999 ) The effectiveness of the Reach for Health Community Youth Service Learning Program in reducing early and unprotected sex among urban middle school students. American Journal of Public Health , 89 , 176 –181.*

Peersman, G., Oakley, A., Oliver, S. and Thomas, J. (1996) Review of Effectiveness of Sexual Health Promotion Interventions for Young People . EPI Centre Report, London.

Quinn, J. ( 1986 ) Rooted in research: effective adolescent pregnancy prevention programs. Journal of Social Work and Human Sexuality , 5 , 99 –110.

Repucci, N. and Herman, J. ( 1991 ) Sexuality education and child abuse: prevention programs in the schools. Review of Research in Education , 17 , 127 –166.

Roche, J. ( 1986 ) Premarital sex: attitudes and behavior by dating stage. Adolescence , 21 , 107 –121.

Roosa, M. and Christopher, F. ( 1990 ) Evaluation of an abstinence-only adolescent pregnancy prevention program: a replication. Family Relations , 39 , 363 –367.*

Rosenthal, R. (1991) Meta-analytic Procedures for Social Research. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Rosenthal, R. and Rubin, D. ( 1982 ) Comparing effect sizes of independent studies. Psychological Bulletin , 92 , 500 –504.

Sexual abstinence program has a $250 million price tag (1997) The Herald Times , Bloomington, Indiana, March 5, p. A3.

St Leger, L. ( 1999 ) The opportunities and effectiveness of the health promoting primary school in improving child health—a review of the claims and evidence. Health Education Research , 14 , 51 –69.

Thomas, G., Reifman, A., Barnes, G. and Farrell, M. ( 2000 ) Delayed onset of drunkenness as a protective factor for adolescent alcohol misuse and sexual risk taking: a longitudinal study. Deviant Behavior , 21 , 181 –210.

Visser, A. and Van Bilsen, P. ( 1994 ) Effectiveness of sex education provided to adolescents. Patient Education and Counseling , 23 , 147 –160.

Walter, H. and Vaughan, R. ( 1993 ) AIDS risk reduction among multiethnic sample of urban high school students. Journal of the American Medical Association , 270 , 725 –730.*

Weeks, K., Levy, S., Chenggang, Z., Perhats, C., Handler, A. and Flay, B. ( 1995 ) Impact of a school-based AIDS prevention program on young adolescents self-efficacy skills. Health Education Research , 10 , 329 –344.*

Zabin, L. and Hirsch, M. (1988) Evaluation of Pregnancy Prevention Programs in the School Context . Lexington Books, Lexington, MA.

- least-squares analysis

- sex education

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2016 | 81 |

| December 2016 | 19 |

| January 2017 | 121 |

| February 2017 | 354 |

| March 2017 | 300 |

| April 2017 | 522 |

| May 2017 | 455 |

| June 2017 | 169 |

| July 2017 | 62 |

| August 2017 | 294 |

| September 2017 | 652 |

| October 2017 | 676 |

| November 2017 | 780 |

| December 2017 | 3,036 |

| January 2018 | 3,200 |

| February 2018 | 3,673 |

| March 2018 | 3,627 |

| April 2018 | 3,139 |

| May 2018 | 2,555 |

| June 2018 | 2,013 |

| July 2018 | 2,148 |

| August 2018 | 2,967 |

| September 2018 | 3,714 |

| October 2018 | 3,798 |

| November 2018 | 4,484 |

| December 2018 | 3,791 |

| January 2019 | 4,188 |

| February 2019 | 4,982 |

| March 2019 | 4,842 |

| April 2019 | 3,557 |

| May 2019 | 3,580 |

| June 2019 | 2,908 |

| July 2019 | 3,725 |

| August 2019 | 3,284 |

| September 2019 | 4,049 |

| October 2019 | 3,720 |

| November 2019 | 3,907 |

| December 2019 | 2,901 |

| January 2020 | 4,396 |

| February 2020 | 5,548 |

| March 2020 | 3,284 |

| April 2020 | 2,201 |

| May 2020 | 1,202 |

| June 2020 | 1,760 |

| July 2020 | 1,564 |

| August 2020 | 1,608 |

| September 2020 | 2,934 |

| October 2020 | 3,212 |

| November 2020 | 3,151 |

| December 2020 | 2,680 |

| January 2021 | 2,758 |

| February 2021 | 3,245 |

| March 2021 | 4,425 |

| April 2021 | 4,718 |

| May 2021 | 3,190 |

| June 2021 | 2,262 |

| July 2021 | 1,203 |

| August 2021 | 875 |

| September 2021 | 2,420 |

| October 2021 | 3,447 |

| November 2021 | 2,645 |

| December 2021 | 1,741 |

| January 2022 | 1,487 |

| February 2022 | 2,249 |

| March 2022 | 3,565 |

| April 2022 | 3,036 |

| May 2022 | 2,295 |

| June 2022 | 1,083 |

| July 2022 | 340 |

| August 2022 | 383 |

| September 2022 | 1,129 |

| October 2022 | 1,537 |

| November 2022 | 1,189 |

| December 2022 | 700 |

| January 2023 | 934 |

| February 2023 | 1,411 |

| March 2023 | 2,047 |

| April 2023 | 1,499 |

| May 2023 | 1,842 |

| June 2023 | 1,445 |

| July 2023 | 354 |

| August 2023 | 387 |

| September 2023 | 674 |

| October 2023 | 797 |

| November 2023 | 697 |

| December 2023 | 447 |

| January 2024 | 705 |

| February 2024 | 767 |

| March 2024 | 747 |

| April 2024 | 950 |

| May 2024 | 625 |

| June 2024 | 312 |

| July 2024 | 88 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

REVIEW article

A systematic review of the provision of sexuality education to student teachers in initial teacher education.

- 1 School of Languages, Law and Social Sciences, Technological University of Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 2 School of Human Development, Institute of Education, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

- 3 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Science & Engineering, Maynooth University, Kildare, Ireland

Teachers, and their professional learning and development, have been identified as playing an integral role in enabling children and young people’s right to comprehensive sexuality education (CSE). The provision of sexuality education (SE) during initial teacher education (ITE) is upheld internationally, as playing a crucial role in relation to the implementation and quality of school-based SE. This systematic review reports on empirical studies published in English from 1990 to 2019. In accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, five databases were searched: ERIC, Education Research Complete, PsycINFO, Web of Science and MEDLINE. From a possible 1,153 titles and abstracts identified, 15 papers were selected for review. Findings are reported in relation to the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) Training Matters: Framework of core competencies for sexuality educators . Results revealed that research on SE during ITE is limited and minimal research has focused on student teachers’ attitudes on SE. Findings indicate that SE provision received is varied and not reflective of comprehensive SE. Recommendations highlight the need for robust research to inform quality teacher professional development practices to support teachers to develop the knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary to teach comprehensive SE.

Introduction

Sexuality education.

Our understanding of sexuality education is ever evolving, and differences exist in the terminology, definitions and criteria employed across various international documentation relating to SE (cf. Iyer and Aggleton, 2015 ; European Expert Group on Sexuality Education, 2016 ). While the term comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) has, in the last decade or so, come to be widely employed ( WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017 ; United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 2018 ), given its more recent common usage, for the purpose of this paper, sexuality education (SE) is the broader term employed.

An international qualitative review of studies which report on the views of students and experts/professionals working in the field of SE ( Pound et al., 2017 ) provides recommendations for effective SE provision. According to that review, effective SE provision should include: The adoption of a “sex positive,” culturally sensitive approach; education that reflects sexual and relationship diversity and challenges inequality and gender stereotyping; content on topics including consent, sexting, cyberbullying, online safety, sexual exploitation, and sexual coercion; a “whole-school” approach and provide content on life skills; non-judgmental content on contraception, safer sex, pregnancy and abortion; discussion on relationships and emotions; consideration of potentially risky sexual practices and not over-emphasize risk at the expense of positive and pleasurable aspects of sex; and the production of a curriculum in collaboration with young people. Similarly, Goldfarb and Lieberman’s (2021) systematic review provides support for the adoption of comprehensive SE that is positive, affirming, inclusive, begins early in life, is scaffolded and takes place over an extended period of time.

Teachers as Sexuality Educators

While there are a variety of sources from which students access information for SE, and diversity in respect of students expressed preferences with regards to SE sources ( Turnbull et al., 2010 ; Donaldson et al., 2013 ; Pound et al., 2016 ), the formal education system remains a significant site for universal, comprehensive, age-appropriate, effective SE. Teachers are particularly well-positioned to provide comprehensive SE and create a climate of trust and respect within the school ( World Health Organisation [WHO]/Regional Office for Europe & Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA, 2010 , 2017 ; Bourke et al., 2022 ). Qualities of the teacher and classroom environment are associated with increased knowledge of health education, including SE, for students. Murray et al. (2019) found that the teacher being certified to teach health education, having a dedicated classroom, and having attended professional development training were associated with greater student knowledge of this subject. Inadequate training, embarrassment and an inability to discuss SE topics in a non-judgmental way have been cited as explanations provided by students as to why they would not consider teachers suitable or desirable to teach SE ( Pound et al., 2017 ).

Walker et al. (2021) in their systematic review of qualitative research on teachers’ perspectives on sexuality and reproductive health (SRH) education in primary and secondary schools, reported that adequate training (pre-service and in-service) was a facilitator that positively impacted on teachers’ confidence to provide school-based SRH education. These findings highlight the importance of quality teacher professional development, commencing with initial teacher education (ITE), for the provision of comprehensive SE. Consequently, ITE has increasingly been proposed as key in addressing the global, societal challenge of ensuring the provision of high-quality SE.

Initial Teacher Education

Teacher education provides substantial affordances to respond to the opportunities and challenges presented in the area of SE ( WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017 ). Furthermore, a research-informed understanding of teacher education is emphasized to better support teacher educators in their work with student teachers ( Swennen and White, 2020 ).

Quality ITE provides a strong foundation for teachers’ delivery of comprehensive SE and the creation of safe and supportive school climates. Research has found that teacher professional development in SE is a significant factor associated with the subsequent implementation of school-based SE ( Ketting and Ivanova, 2018 ). A recent Ecuadorian study reported that student teachers held a relatively high level of confidence in terms of their perceived ability to implement SE and to address specific CSE topics. Furthermore, favourable attitudes toward CSE, strong self-efficacy beliefs to implement CSE, and increased confidence in the ability to implement CSE were significantly associated with positive intentions to teach CSE in the future. Insufficient mastery of CSE topics, however, may temper student teachers’ intentions to teach CSE ( Castillo Nuñez et al., 2019 ). Internationally, research suggests there is inconsistency in the provision of SE in ITE and that access to professional development in SE in ITE, and after qualification, needs substantial development ( United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO] , 2009 , 2018 ; Ketting et al., 2018 ; O’Brien et al., 2020 ).

Research is thus warranted to explore aspects at the institutional, programmatic and student-teacher level at ITE to address issues regarding the provision, and barriers to SE provision during ITE. Contemporaneous to the current review, O’Brien et al. (2020) undertook a systematic review of teacher training organizations and their preparation of student teachers to teach CSE. They found that teacher training organizations are often strongly guided by national policies and their school curricula, as opposed to international guidelines. They also found that teachers are often inadequately prepared to teach CSE and that CSE provision during ITE is associated with greater self-efficacy and intent to teach CSE in schools. The importance of ITE with regards to the provision of SE cannot be underestimated. Teachers are in an optimal position to provide age-appropriate, comprehensive and developmentally relevant SE to all children and young people.

The current systematic review will assess the provision of SE to student teachers in ITE and how this relates to the relevant knowledge, attitudes and skills required of sexuality educators as proposed by the international guidelines produced by the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) . The WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) Training Matters: Framework of core competencies for sexuality educators adopts a holistic definition of core competencies, espousing an understanding of teacher competencies as “…overarching complex action systems” and as multi-dimensional, made up of three components: attitudes, skills and knowledge ( WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017 , p. 20). This framework outlines a set of general competencies, together with more specific attitudes, skills and knowledge competencies for sexuality educators. Attitudes, which may be explicit or implicit, are understood as a factor pertaining to the influencing and guiding of personal behaviour. Skills are understood in terms of the abilities educators can acquire which enables them to provide high-quality education. While knowledge is understood as professional knowledge (pedagogical knowledge, content knowledge and pedagogical subject knowledge) in all relevant areas required to deliver high-quality education. Overall, the framework endorses a holistic and multi-dimensional approach which focuses on sexuality educators and the inter-related competencies, in relation to the knowledge, attitudes, and skills that they should have, or need to develop to become effective teachers of SE.

Aims and Objectives

The current study aimed to systematically review existing empirical evidence on the provision of SE for student teachers in the context of ITE.

The objectives were:

• To review the existing peer-reviewed, published literature on SE provision during ITE.

• To synthesize the research on SE provision at ITE institutional/programmatic level.

• To synthesize the research on individual level student teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills in relation to SE during ITE.

Materials and Methods

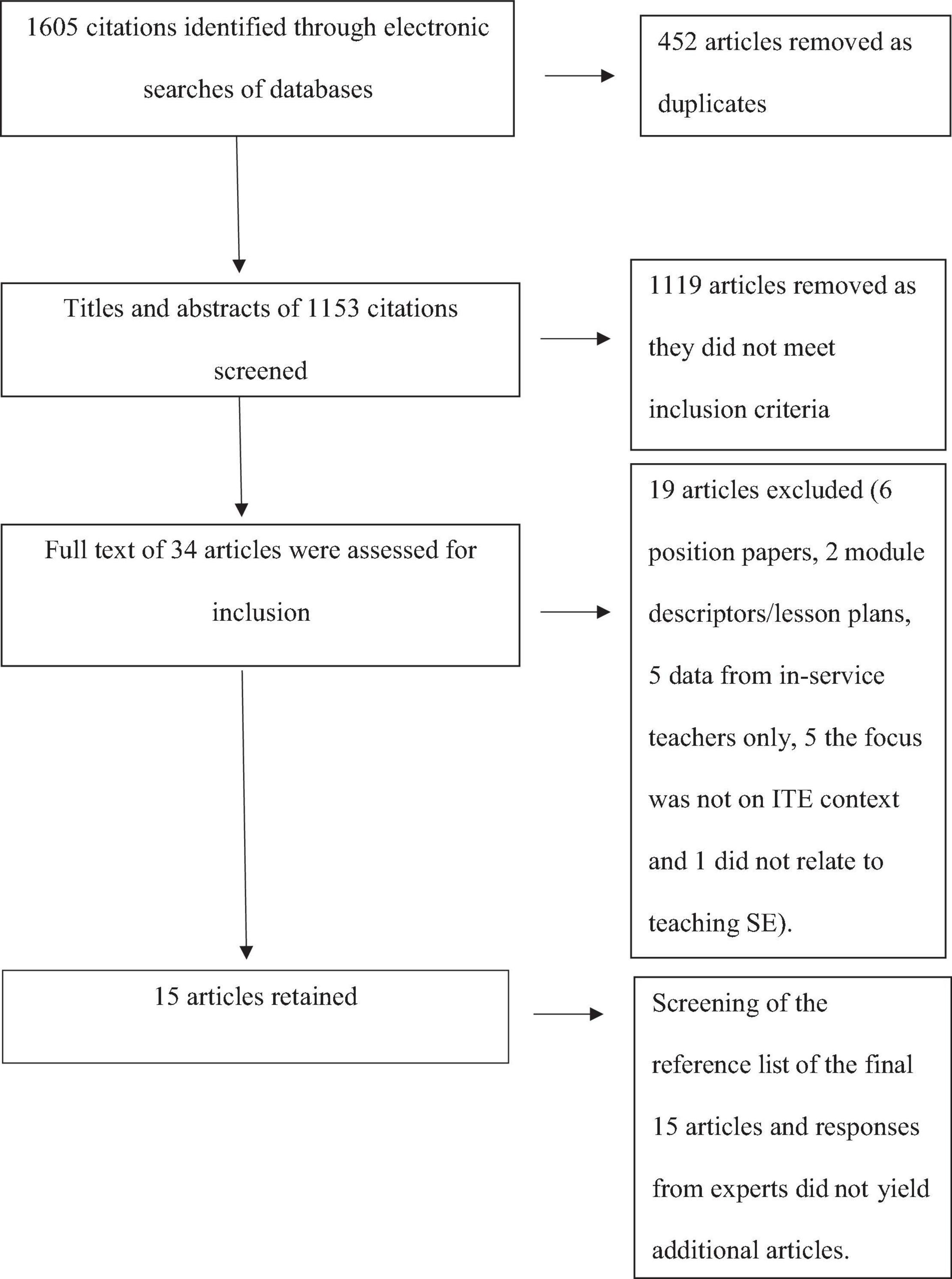

The systematic review was completed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines ( Liberati et al., 2009 ). A descriptive summary and categorization of the data is reported ( Khangura et al., 2012 ).

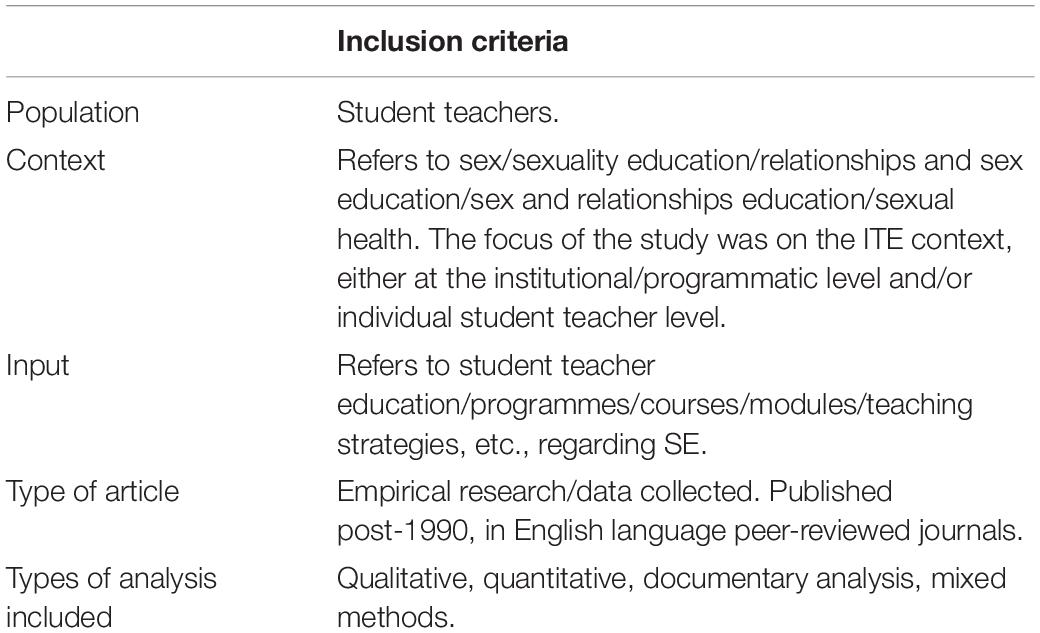

Eligibility Criteria

Articles were included in the review subject to adherence to specific inclusion criteria. An overview of inclusion criteria is outlined in Table 1 .

Table 1. Screening and selection tool.

Information Sources

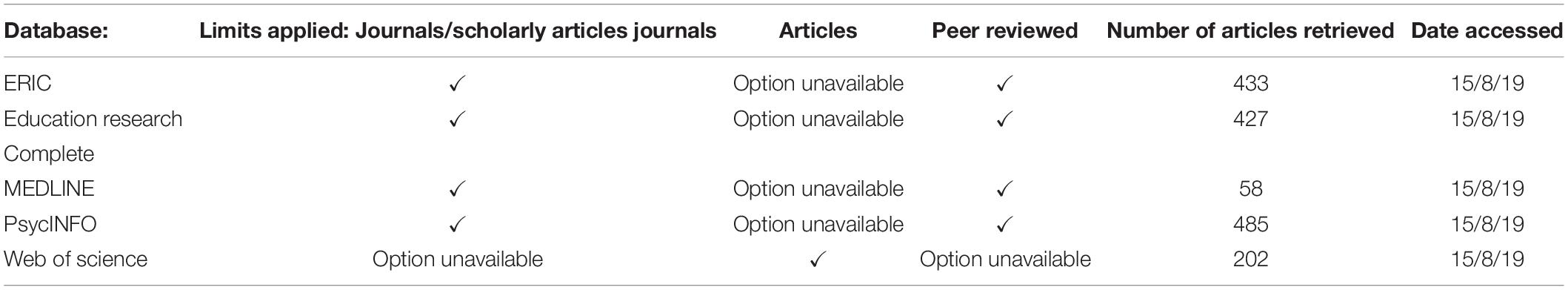

A three-reviewer process was employed. Searches were conducted in August 2019 on five databases selected for their ability to provide a focused search within the disciplines of education (ERIC and Education Research Complete), psychology (PsycINFO), and multi-disciplinary research in the disciplines of health/public health (Web of Science and MEDLINE).

Screening and Study Selection

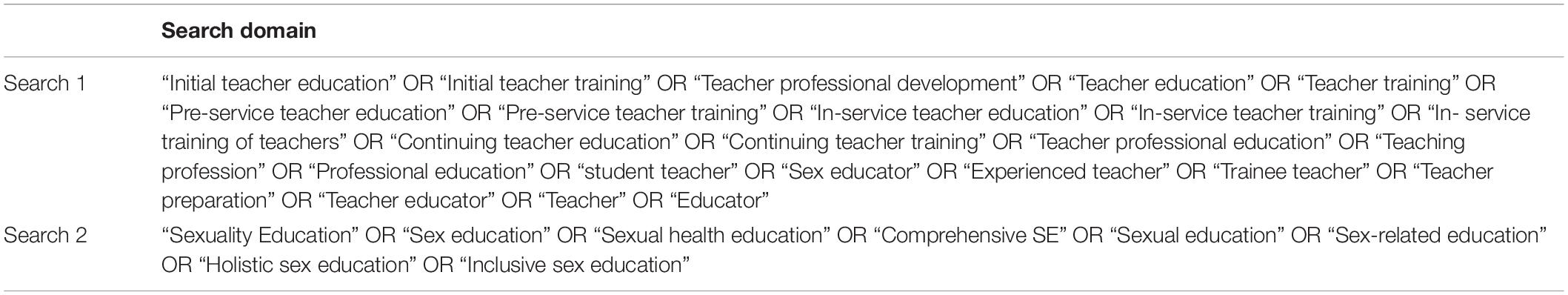

Reviewers’ selected keywords from two domains, namely ITE and SE as outlined in Table 2 , for the searches. Search terms for each domain were combined using the Boolean search function “AND.”

Table 2. Overview of Systematic Review search terms.

Where possible, limits were applied to include articles from peer reviewed journals as outlined in Table 3 .

Table 3. Overview of database searches and limits applied.

In accordance with Boland et al. (2017) , a pilot screening of a sample of titles and abstracts were completed by two reviewers to assess the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All titles and abstracts were then screened using Abstrackr software ( Abstrackr, 2010 , accessed 2019; Wallace et al., 2010 ). A selection of abstracts were then cross checked by two reviewers. The final selection involved a three reviewer process. Duplicates and references which did not meet the eligibility criteria were removed at this stage. Full text papers of the remaining articles were obtained, where possible. All three reviewers blindly screened the texts of the remaining articles. Consensus was reached that 15 articles met the criteria for this review. Two experts in the field of SE reviewed the list of 15 articles to ensure there were no outstanding papers for consideration within the parameters of the review. No additional papers were identified.

Data Collection Process

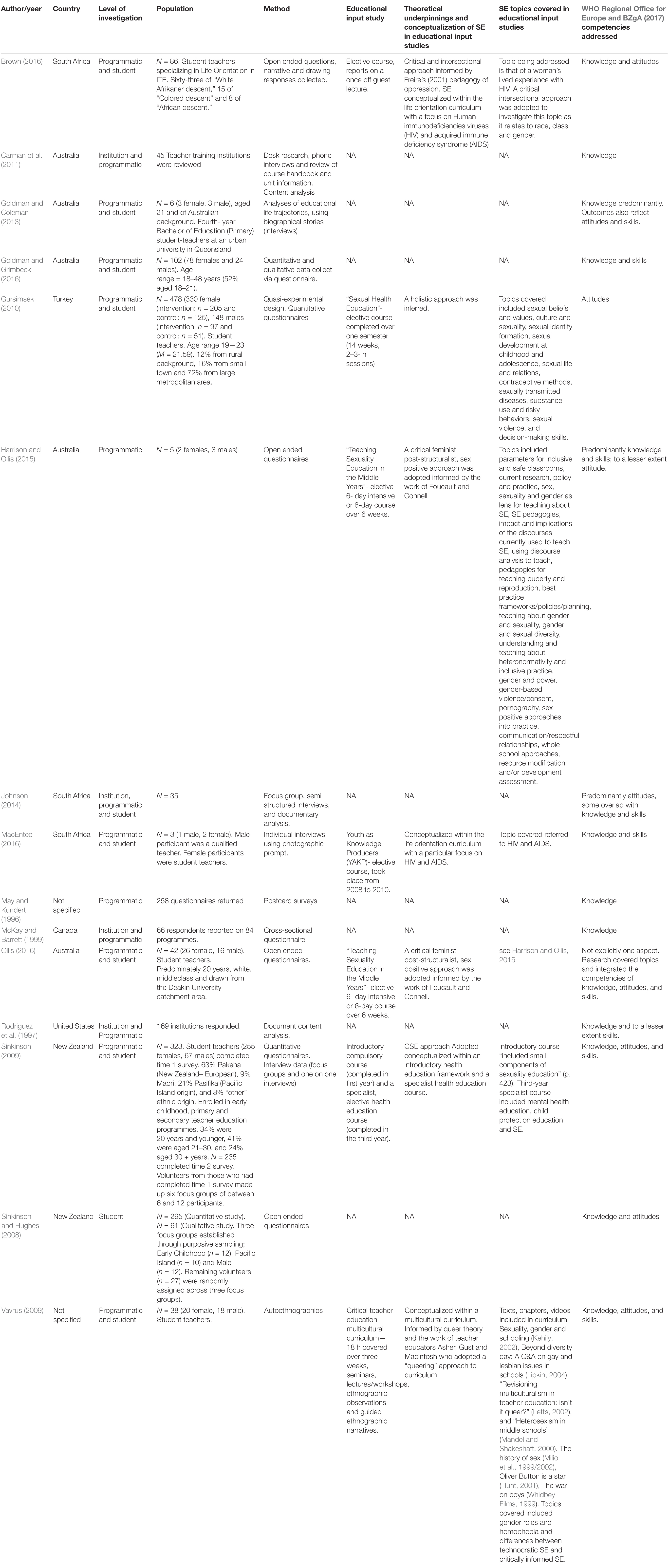

A data extraction template was devised in accordance with Boland et al.’s (2017) recommendations. Information was collected on each study regarding: participant characteristics (data on participant gender, age, programme and institution of study, ethnicity, socio-economic status and religion were extracted, where provided); whether the studies examined programmatic input and if so the duration/extent of input; theoretical and conceptualization of SE within the programme; topics covered; whether this was a compulsory or elective programme; and whether the study addressed the WHO-BZgA competencies of knowledge, attitudes and skills of student teachers during ITE ( WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017 ). One lead author was contacted for the purpose of data collection and provided further information regarding their study.

Synthesis of Results

A qualitative synthesis was conducted; the purpose of which was to provide an overview of the evidence identified regarding research on the provision of SE in the ITE context. The findings of the reviewed studies were synthesized following consideration of the key learnings and recommendations from the studies and consideration of the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) competencies of knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary for the provision of SE at ITE. The WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) framework was selected to support the categorization and analysis of findings as it was developed by global experts in the field and is thus, an international standard for SE. While there are limitations to the use of this framework, it offered the ability to categorize and analyze findings through a multi- dimensional lens of knowledge, attitudes, and skills.

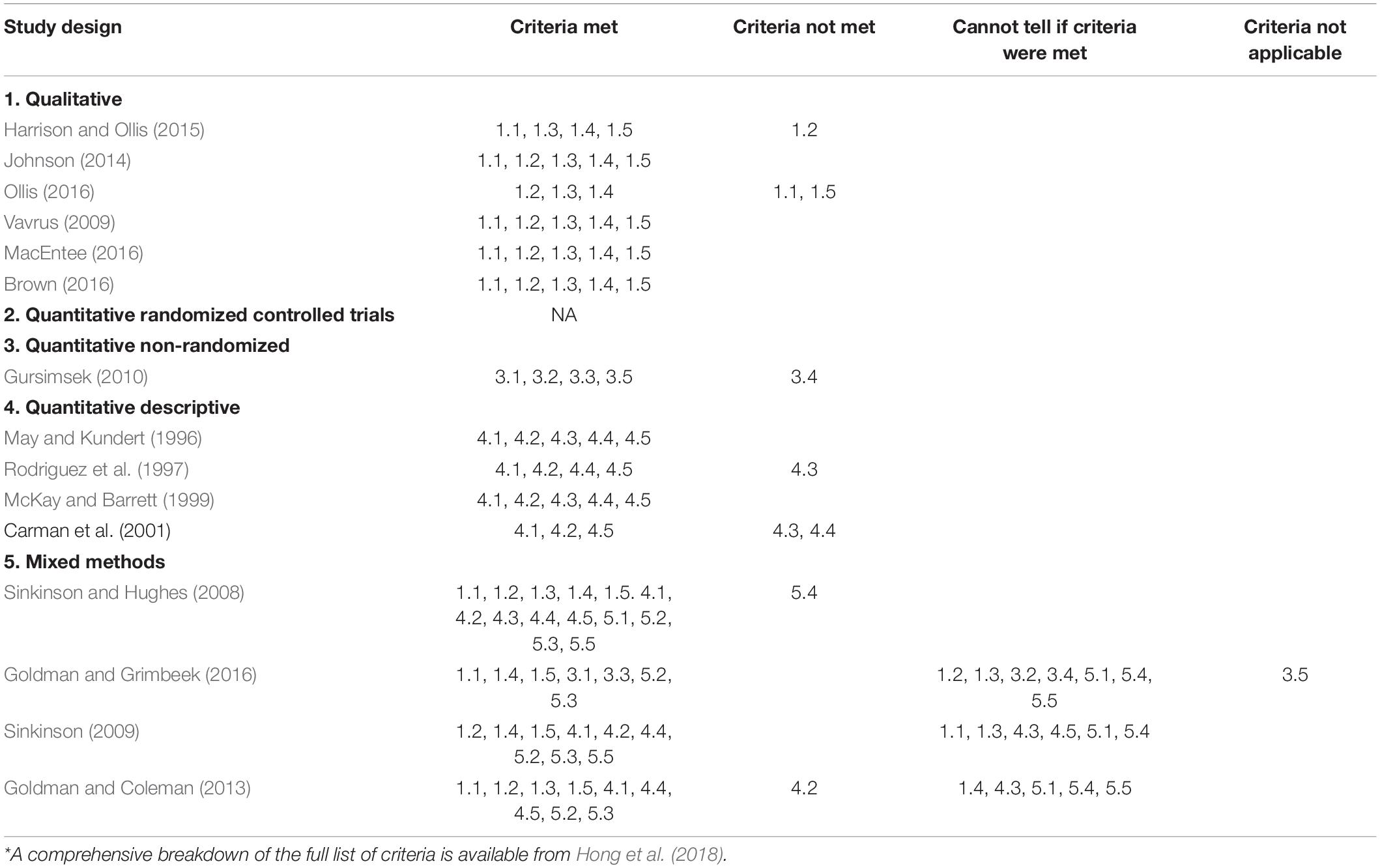

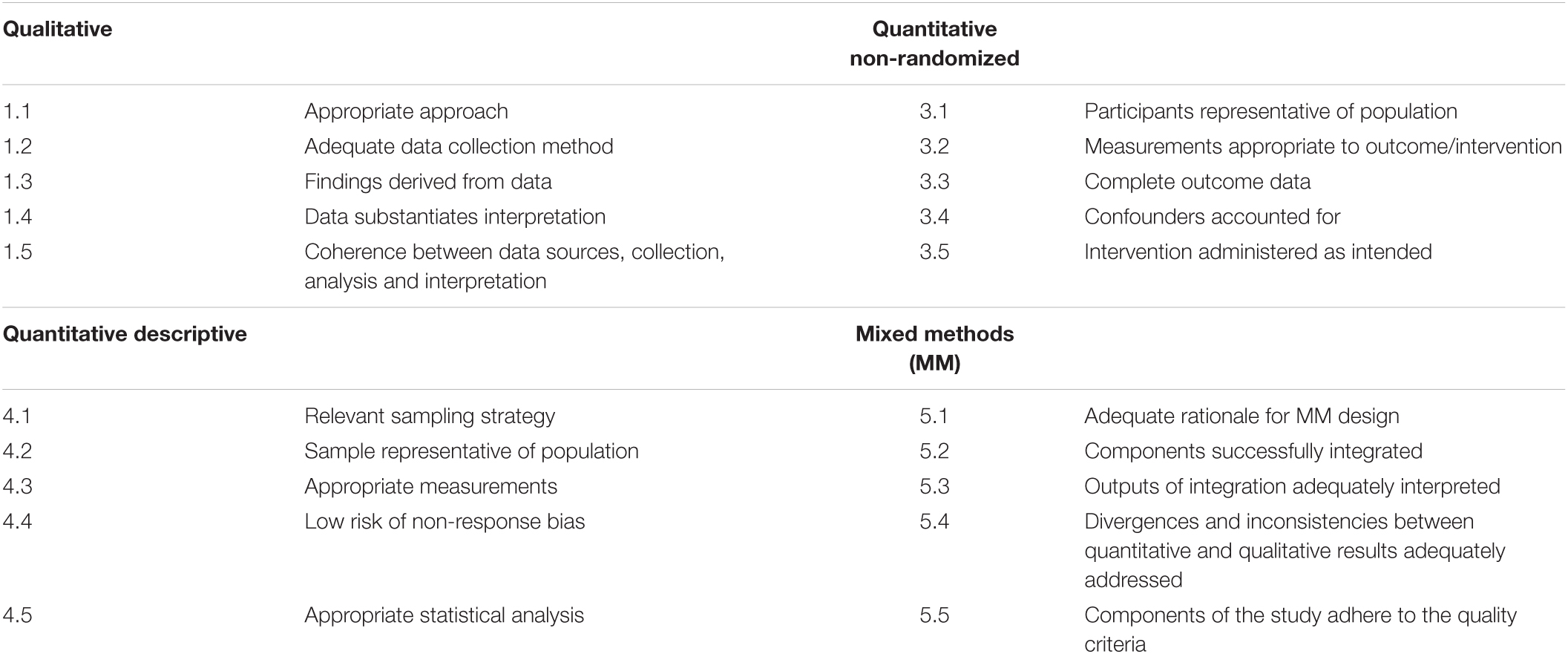

Quality Appraisal

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) ( Pluye et al., 2009 ; Hong et al., 2018 ) was used to appraise the quality of papers by two reviewers. This tool has been found to be reliable for the appraisal of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies ( Pace et al., 2012 ; Taylor and Hignett, 2014 ) and has been successfully used in previous systematic reviews (e.g., McNicholl et al., 2019 ). For each paper, the appropriate study design was selected (i.e., 1. Qualitative, 2. Quantitative randomized controlled trials, 3. Quantitative non-randomized, 4. Quantitative descriptive, and 5. Mixed methods). Next, the paper was assessed using the checklist associated with the study design (see Appendix A for overview of checklist). For example, if the study was categorized as 4. Quantitative descriptive, the study was assessed against the five criteria (4.1–4.5) associated with this study design. An example of a question on the checklist includes “Are the measurements appropriate?” criteria were reported as “met,” “not met,” “cannot tell if criteria were met” or “criteria not applicable.” The results of the quality appraisal are presented in Table 4 . The same numbering as the methodological quality criteria of Hong et al.’s (2018) study was used.

Table 4. MMAT quality appraisal.*

Study Selection

Fifteen articles reporting on thirteen empirical studies were included in the review (see Figure 1 ). Harrison and Ollis (2015) and Ollis (2016) articles are derived from the same dataset, as are Sinkinson and Hughes (2008) and Sinkinson (2009) articles. Given, however, that these articles refer to unique aspects of the particular studies, they have been described and discussed as separate studies in this review. An overview of the process of screening and study selection is outlined in Figure 1 .

Figure 1. Flow diagram of systematic review process.

Study Characteristics

Six qualitative, five quantitative, and four mixed methods studies were reviewed. Where information was available, the research studies were identified as having been conducted predominantly in Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. The studies were published between 1996 and 2016. Data was most frequently collected from one source; student teachers ( n = 10) and teacher educators/course providers ( n = 3). One study collected data from both student teachers and teacher educators/course providers ( Johnson, 2014 ). The samples size of studies varied from three to 478 participants but were generally small (eight of the studies had fewer than 90 participants: Vavrus, 2009 ; Carman et al., 2011 ; Goldman and Coleman, 2013 ; Johnson, 2014 ; Harrison and Ollis, 2015 ; Brown, 2016 ; MacEntee, 2016 ; Ollis, 2016 ).

Seven studies assessed SE educational inputs at ITE, and three conducted content analysis of content covered on SE educational input at ITE. As the studies were predominantly descriptive and explorative in design, specific outcome variables were often neither defined nor addressed. Educational input studies were classified as examples of research which assessed a particular course, module, or lecture on SE at ITE. With regards to theoretical approaches that may have informed the educational input studies reviewed, three did not report a specific theoretical approach ( Sinkinson, 2009 ; Gursimsek, 2010 ; MacEntee, 2016 ), and the remaining four reported that a critical approach was adopted ( Vavrus, 2009 ; Harrison and Ollis, 2015 ; Brown, 2016 ; Ollis, 2016 ). An overview of study characteristics are presented in Table 5 .

Table 5. Overview of characteristics of reviewed studies.

Quality Appraisal Results

An overview of the results of the MMAT are presented in Table 4 . All the papers in the review were empirical studies and therefore could be appraised using the MMAT. Predominantly the studies reviewed employed the use of qualitative methods, and of the mixed methods studies there was often an emphasis on the qualitative data. Generally, the quality of the mixed methods studies was varied with only a minority of these studies providing a rationale for the use of mixed methods and reporting on divergences between the qualitative and quantitative findings.

The rigour and quality of the qualitative research was also varied. An explicit statement of the epistemological stance adopted and detail of the analytical process were reported in a minority of studies. With regards to educational input studies, data was often collected only after the educational input was completed and thus behavioral change as a result of engagement in the educational input could not be ascertained (e.g., Harrison and Ollis, 2015 ; MacEntee, 2016 ; Ollis, 2016 ). Only one study employed a quasi-experimental design ( Gursimsek, 2010 ), and in this case a purposive sample of student teachers who did not complete the SE course was selected as the control group. Within the remaining 14 studies there were no control groups, randomization, or concealment.

Findings are reported in relation to (a) institutional/programme level and (b) individual student teacher level aligned with the World Health Organisation ( WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017 ) Training Matters: Framework of Core Competencies for Sexuality Educators . An awareness of the interaction of these aspects of student teachers’ development was informative in terms of structuring the findings.

The research studies reviewed predominantly focused on examining a particular educational input on SE during ITE ( Sinkinson, 2009 ; Vavrus, 2009 ; Gursimsek, 2010 ; Harrison and Ollis, 2015 ; Brown, 2016 ; MacEntee, 2016 ; Ollis, 2016 ) or investigating the SE content covered during ITE ( Rodriguez et al., 1997 ; McKay and Barrett, 1999 ; Carman et al., 2011 ). Fewer of the reviewed studies focused on student teachers’ skills to teach SE (e.g., Sinkinson, 2009 ; Vavrus, 2009 ; Harrison and Ollis, 2015 ; Goldman and Grimbeek, 2016 ; MacEntee, 2016 ) or student teachers’ attitudes regarding SE (e.g., Sinkinson and Hughes, 2008 ; Sinkinson, 2009 ; Vavrus, 2009 ; Gursimsek, 2010 ; Johnson, 2014 ; Brown, 2016 ). The findings of the studies were synthesized and categorized in relation to institutional/programmatic level or individual student teacher level. Findings which reflected responses and perceptions of student teachers were categorized as individual student teacher level. Institutional/Programme level related to studies assessing particular modules or comparing course content across programmes, and institutional level studies were categorized as studies where data was collected from multiple institutions. Individual student teacher level findings were reported in relation to the knowledge, attitudes, and skills competency areas required of sexuality educators. These competency domains, however, are not discrete entities or mutually exclusive. In taking a systemic approach, it is, therefore, acknowledged that they are dynamically interconnected, and influence and interact.

Institutional/Programme Level Findings

At a programmatic level, studies revealed variance in the type of SE provision (core/mandatory and elective), student teachers receive during ITE. May and Kundert (1996) found that coursework on SE was reported as part of a mandatory course by 66% of respondents and as part of an elective course by 14% of respondents. While McKay and Barrett (1999) reported that only 15% of the health education programmes in their study offered mandatory SE training with 26% of programmes offering an elective component. With regards to the provision of skill development and training for SE that student teachers received during ITE, Rodriguez et al. (1997) found that of a potential 169 undergraduate programmes, the majority (i.e., 72%) offered some training to student teachers in health education: A minority offered teaching methods courses in SE (i.e., 12%) and HIV/AIDS prevention education (i.e., 4%). Two of the reviewed studies also investigated programme time allocated to SE and found that time spent on SE varied from 3.6 hours ( May and Kundert, 1996 ) to between 9.6 and 36.2 hours ( McKay and Barrett, 1999 ). While at an institutional level, Carman et al. (2011) found that eight of 45 teacher training institutions did not offer any training in SE and of those that did, 62% offered mandatory, and 38% elective inputs.

Findings indicate the paucity of SE topics covered across ITE programme curricula. Rodriguez et al. (1997) reported that 90% of the courses they reviewed listed a maximum of three SE topic areas. The top three SE topics reported in terms of coverage were human development, relationships, and society and culture. Somewhat consistently, McKay and Barrett (1999) found that the topics least emphasized on courses were masturbation, sexual orientation, human sexual response, and methods of sexually transmitted disease prevention. Johnson (2014) sought to examine coverage of, what they defined as, “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual and intersexual (LGBTI)” (p. 1249) issues on ITE courses and reported that of the three ITE institutions examined, none specifically reference LGBTI issues. Finally, one study reported that the provision of SE was found to be contingent on the interest and expertise of the university teacher educators ( Carman et al., 2011 ). Collectively, these findings bring to light the variance in mandatory and/or elective SE provision during ITE, as well as the diverse content covered and the role of teacher educators on its provision.

Individual Student Teacher Level Findings

Factors associated with student teachers’ attitudes regarding sexuality education topics.

Gender, geographical location, religious beliefs, and family background were identified as factors associated with student teachers’ attitudes regarding SE ( Sinkinson and Hughes, 2008 ; Gursimsek, 2010 ; Johnson, 2014 ). Attending a SE course may have positive implications for student teachers’ attitudes as Gursimsek (2010) found that students who had not attended the SE course reported more conservative and prejudiced views toward sexuality than those who had attended the SE course. Given that this was an elective course, however, it is important to consider self-selection bias regarding those who may have opted to take the course.