The Emotion Amplifier Thesaurus , a companion to The Emotion Thesaurus , releases May 13th.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

WRITERS HELPING WRITERS®

Helping writers become bestselling authors

Emotion Thesaurus Entry: Jealousy

March 6, 2008 by ANGELA ACKERMAN

When it comes to emotion, sometimes we need a brainstorming nudge. After all, each character will express their feelings differently depending on their personality, emotional range, and comfort zone. We hope this short, sample list of expressions will help you better imagine how your character might show this emotion!

If you need to go deeper , we have detailed lists of body language, visceral sensations, dialogue cues, and mental responses for 130 emotions in the 2019 expanded second edition of The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression .

- Sullen looks, glowering

- Hot eyes, tears forming

- Sitting against a wall, holding the knees to the chest and staring off angrily

- Minor destruction as a release (crumpling paper or breaking pencils)

- Rash decisions (impulsively quitting a team or storming out of a party)

- Jeering, calling names, running someone down

- Starting rumors, acting catty

- Shoving the person who caused the jealous feelings

- Showing off

- A desire for revenge

- Reckless behavior (trusting a stranger, using drugs or alcohol…

Win your readers’ hearts by tailoring your character’s emotional responses so they’re compelling, credible, and realistic.

Prefer the flexibility of instant online access and greater searchability?

The Emotion Thesaurus is also at our sister site, One Stop for Writers . Visit the Emotion Thesaurus Page to view our complete list of entries.

TIP: While you’re there, check out our hyper-intelligent Character Builder that helps you create deep, memorable characters in half the time !

Angela is a writing coach, international speaker, and bestselling author who loves to travel, teach, empower writers, and pay-it-forward. She also is a founder of One Stop For Writers , a portal to powerful, innovative tools to help writers elevate their storytelling.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Reader Interactions

May 28, 2020 at 2:41 pm

So good! Thank you! I’ve just purchased 4 of your books because of this one post.

May 29, 2020 at 10:37 am

Oh, I’m so glad to hear it, Tammy. Happy that this post and our books are helping you out. Best of luck!

August 16, 2011 at 9:14 am

This blog is great. I have a character in my story who’s jealous of my M.C. and all I have so far is “he was jealous” statements, that get boring after a while.

August 8, 2008 at 8:12 pm

I was just told by a publisher purchasing my work to remove all “she was jealous” type statements and replace with showing…

Here is where I went immediately. 😀

Cookies and flowers to you guys for the theasurus!

March 6, 2008 at 3:20 pm

Jay! Another entry for the emotion thesaurus. Thanks.

Your faithful lurker. 🙂

[…] Conveying Jealousy […]

The Enlightened Mindset

Exploring the World of Knowledge and Understanding

Welcome to the world's first fully AI generated website!

How to Describe Jealousy in Writing: Examples, Benefits and Tips

By Happy Sharer

Introduction

Jealousy is a complex emotion that can arise when someone feels threatened by perceived competition from another person or entity. It is often characterized by feelings of insecurity, fear of abandonment, suspicion, and envy. While jealousy is a natural emotion, it can also become destructive if it becomes too intense or prolonged. Writing about jealousy can be a challenging task, as it is often difficult to convey its complexities with words. In this article, we will explore how to describe jealousy in writing, providing examples, benefits, and tips.

Use imagery to illustrate the feeling of jealousy

Imagery is one of the most powerful tools for conveying emotions in writing. To accurately describe jealousy in writing, it’s important to use vivid images that capture the intensity and complexity of the emotion. For example, you might compare jealousy to a storm raging inside someone’s chest, or to an invisible leash that binds two people together. Imagery can help readers to empathize with the character and understand their emotional state more deeply.

Show how jealousy can cause physical reactions

In addition to emotional reactions, jealousy can also elicit physical responses. These physical reactions can range from a racing heart to clammy hands to clenched fists. Describing these physical reactions can help to further illustrate the intensity of the emotion. For example, you could write that “his heart raced as he watched the couple dancing together, his fists clenching at his sides.” This type of detail can make the scene come alive for the reader and give them a better understanding of the character’s emotional state.

Describe thoughts and emotions that come with jealousy

When describing jealousy, it’s also important to include the thoughts and emotions that accompany it. These can include feelings of insecurity, fear of abandonment, suspicion, anger, and envy. You can illustrate these thoughts and emotions by showing how they play out in the character’s behavior. For example, you might write that the character “was consumed by thoughts of betrayal, her suspicions growing with every passing minute.” This type of detail can help readers to connect with the character on a deeper level and understand their inner turmoil.

Demonstrate how jealousy can manifest itself in behavior

When writing about jealousy, it’s important to show how the emotion manifests itself in the character’s behavior. This can include both verbal and physical actions, such as lashing out at others, withdrawing from social situations, or avoiding certain topics of conversation. By demonstrating how jealousy affects the character’s behavior, you can help readers to better understand the emotion and its effects on the character.

Show how jealousy can lead to irrational thoughts and decisions

Jealousy can lead to irrational thoughts and decisions, which can have lasting consequences. It’s important to portray these irrational thoughts and decisions in order to demonstrate how the emotion can affect the character’s behavior. For example, you might write that “in his jealousy, he made a rash decision that would haunt him for years to come.” This type of detail can help readers to gain insight into the character’s thought process and make them more sympathetic to their struggle.

Share anecdotes from other people who have experienced jealousy

Another effective way to describe jealousy in writing is to share anecdotes from other people who have experienced the emotion. Anecdotes can help to bring the emotion to life for the reader and add depth to your story. For example, you might include a quote from someone who has dealt with jealousy in the past, or a story about a time when jealousy affected someone’s life. These types of anecdotes can help readers to connect with the character on a personal level and understand the emotion in a new light.

Highlight the contrast between jealousy and envy

It’s also important to highlight the contrast between jealousy and envy in order to accurately portray the emotion. While jealousy is an emotion that arises when someone feels threatened by perceived competition, envy is an emotion that arises when someone desires something that someone else has. By contrasting these two emotions, you can help readers to better understand the nuances of jealousy and how it differs from envy.

In conclusion, jealousy is a complex emotion that can be difficult to accurately portray in writing. However, by using imagery, physical reactions, emotions, behaviors, irrational thoughts, anecdotes, and the contrast between jealousy and envy, you can effectively describe jealousy in your writing. By doing so, you can help readers to empathize with the characters and understand their struggles in a more meaningful way.

(Note: Is this article not meeting your expectations? Do you have knowledge or insights to share? Unlock new opportunities and expand your reach by joining our authors team. Click Registration to join us and share your expertise with our readers.)

Hi, I'm Happy Sharer and I love sharing interesting and useful knowledge with others. I have a passion for learning and enjoy explaining complex concepts in a simple way.

Related Post

Unlocking creativity: a guide to making creative content for instagram, embracing the future: the revolutionary impact of digital health innovation, the comprehensive guide to leadership consulting: enhancing organizational performance and growth, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Expert Guide: Removing Gel Nail Polish at Home Safely

Trading crypto in bull and bear markets: a comprehensive examination of the differences, making croatia travel arrangements, make their day extra special: celebrate with a customized cake.

Search for creative inspiration

19,890 quotes, descriptions and writing prompts, 4,964 themes

jealousy - quotes and descriptions to inspire creative writing

- a toxic culture

- jealous world

- sexual jealousy

Jealousy is so last season, empathy is what's on all the catwalks.

Jealousy eats you up from within until you are a zombie corpse, feasting on the hive-mind.

Jealousy is easier to see than one might expect, it for sure has no cloak of invisibility.

One who grows their passions and own sense of mission is too happy to develop jealousy.

Jealousy is lousy, you should upgrade to cheerleader.

When you follow your own dreams, the reason for your birth, jealousy will evaporate.

The one who follows their divine passions and path, has vices replaced by virtue automatically.

Stupid Eric is giggling again, unmanly it is, his muscles are shaking and tears stream from his half closed eyes. I hold my breath behind pursed lips to steel myself against the gales of laughter to come. They always do. I know what's happened, Sarah just told a lame joke and now their bonding over it in their j-crew vanilla clothes. Well I won't be here next week, I'm off to Hawaii by myself. The brochure looks amazing and I'm travelling first class all the way. Now Eric's telling some lame story about his kid, I know he is without listening to the words. His face is lit up brighter than a toothpaste commercial and he has that soft look on his face. Makes we wanna hurl. Thank God I've got a facial after work, I can put all this crap behind me and de-stress.

Jealousy is often an expression of insecurity and thus its fixing requires internal reflection and addressing matters of self esteem.

Sign in or sign up for Descriptionar i

Sign up for descriptionar i, recover your descriptionar i password.

Keep track of your favorite writers on Descriptionari

We won't spam your account. Set your permissions during sign up or at any time afterward.

Jealousy – How To Craft The Perfectly Jealous Character To Catalyze Conflict In Your Novel

This is one emotion that we all know and have experienced to some degree. Feeling jealous of others is probably not your favourite emotion, but it’s a catalyst for conflict in your story or between your characters. Jealousy can make your character feel more relatable and real to your reader.

Jealousy in writing is effective when it helps a character realise what they really want and how badly they want it. This emotion does not have to be central to the plot of your story; it can be understated and supported by anger or fear.

It comes across in simple examples like a villain who is jealous of the hero, when two characters want one thing/ have the same goal or when one character is more successful than the other.

How to write about a jealous character:

Know the types of jealousy:

- Sexual Jealousy – when a character’s spouse or significant other displays or expresses sexual interest in someone other than your character.

- Romantic Jealousy – when your character fears the loss of a romantic partner or fears rejection from a potential or current romantic partner.

- Possessive Jealousy – when he/she is feeling threatened by someone who could interrupt a friendship or relationship that they value.

- Separation Jealousy – when your character has fear of separation or loss of a lover, partner, friend or parent due to their relationship with another person.

- Work Jealousy – when your character feels cheated out of a promotion at work, or feels jealousy towards a specific person at work.

- Friend/ Sibling Jealousy – When he/she feels inadequate when comparing themselves to their friends/family/siblings. They always try to one-up their friend/sibling.

- Abnormal Jealousy – extreme psychological jealousy that results in or a combination of morbid, psychotic, psychological, delusional, anxious, controlling, immature and insecure behavior.

Understand what fuels your character’s jealousy

Is it confusion, frustration, powerlessness, rejection, worry, insecurity, immaturity, poor self-esteem, underachievement, possessiveness, shame, paranoia, humiliation, fear of loss, suspicion, loneliness, distrust or a combination of these?

How does jealousy affect your character physically?

Do they have an increased heart rate or body temperature? Do they become angry and clench their fist, have verbal outbursts, stare downs and tensed muscles? Do they become quiet and have a dry mouth?

How does your character react towards others or the person they are jealous of?

Does he or she:

- Make up stories or gossip about the person they are jealous of so that others will have negative feelings towards the same person.

- Feel overwhelmed and underachieve in every sphere of their life.

- Avoid the person all together.

- Take up a bad habit or addiction in an attempt to deal with their feelings.

- Become obsessed about something like over exercising and dieting to beat their rival in a tournament or something more sinister like plotting another character’s demise.

- Manipulate others into feeling sorry for them.

- Over criticize themselves and everything they do.

- Harm themselves, their environment or others.

- Show a blatant disregard for the needs and desires of others to fulfill their own.

- Bully or intimidate the people around them to gain a false sense of power.

- Abuse others physically or psychologically.

- Flaunt their wealth, fame, intelligence, status, beauty, etc. to mask their own insecurities.

Why does your story need jealousy?

The physical fight or confrontation that results from jealous behavior advances your plot.

It reveals facets of your character that your reader may not expect.

It is a way for you to show how jealousy affects your character and how they deal with it.

Here are some questions to help you craft a jealous character:

What is important to your character?

Who or what is your character jealous of?

How does this jealous feeling affect your character?

What does this tell your reader about them?

Does this jealousy stem from anger or fear?

What is your character fighting for?

Why does he/she feel insecure?

Is their jealousy justified?

How do they express this jealousy?

Is jealousy part of their personality or is it a fleeting emotion?

How does he/she resolve or plan to resolve the feeling of jealousy?

Famous movies and books that have jealous characters:

Othello, Mean Girls, The Breakfast Club, Bridesmaids, Ratatouille, Atonement, Beauty and The Beast, Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs, Titanic, The Danish Girl, Gone With The Wind, Brooklyn, Moulin Rouge!, Edward Scissorhands, Peter Pan, West Side Story, The Girl on the Train and Persuasion.

Do you use jealousy as a theme in your stories? Do you have any tips for crafting jealous characters? Who is your favourite jealous character of all time? What is your favourite movie/series/book that has a jealous character? Let me know by commenting below!

Love and Blessings,

Feel free to follow me on social media:

Visit my Amazon Author Page and support me by buying a book or two or drop me an email at [email protected].

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Published by Lindsay

Hi there! I’m Lindsay, a passionate self-published author of 29 books, self-taught illustrator, wife and mom living in Nairobi. When I’m not working you’ll find me eating pizza, binging on reality TV, Pinning, crafting or baking. Join me as I learn more about myself and show you how to love life daily! View all posts by Lindsay

2 thoughts on “ Jealousy – How To Craft The Perfectly Jealous Character To Catalyze Conflict In Your Novel ”

Edmund from the Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a pretty developed jealous character. Loved that book as a kid

- Pingback: Analysing this year’s A to Z Challenge

Leave a comment Cancel reply

super wings, super wings toys, Super Wings Parade, super robot suit, Super Wings adventures, The Robot Suit, super wings playset, Super robot suit, Super-Speedy, super wings adventures,super wings jett, super wings transformers, Robocar, robot fight

...one writing step at a time

HUMOR - THRILLER - ABSURD - PULP NOIR - SATIRE - COMEDY

Exposing Truth

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

100+ Jealous Character Traits

The ProWritingAid Team

Table of Contents

Possible causes of being jealous, attitudes related to being jealous, thoughts and struggles associated with being jealous, emotions related to jealousy, facial expressions associated with being jealous, body language related to being jealous, behaviors associated with being jealous, growth and evolution of jealous characters, stereotypes of jealous characters to avoid, negatives of being jealous, positives of being jealous, verbal expressions of jealous characters, relationships of jealous characters, examples from books of characters who are jealous, writing exercises for writing jealous characters.

To engage your reader, it's important to always show, not tell, the traits of your characters.

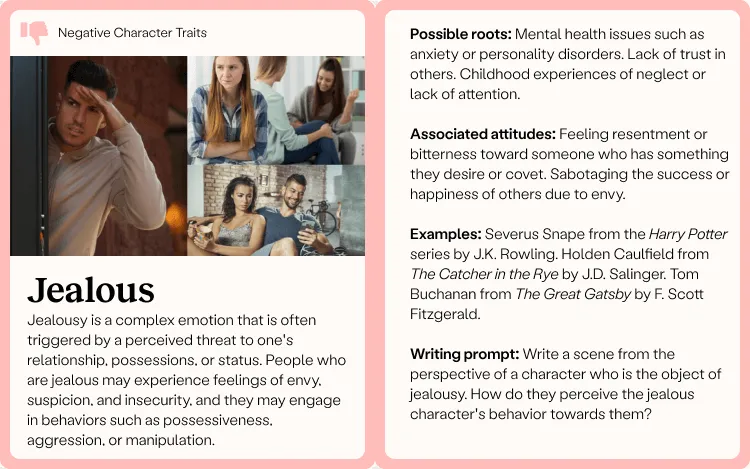

Jealousy is a complex emotion that is often triggered by a perceived threat to one's relationship, possessions, or status. People who are jealous may experience feelings of envy, suspicion, and insecurity, and they may engage in behaviors such as possessiveness, aggression, or manipulation. Jealousy can be a negative trait when it leads to harmful actions or thoughts, but it can also be a natural and healthy response in certain situations, such as when it motivates people to protect their loved ones or strive for personal growth.

As a writer, portraying jealousy in a nuanced and realistic way can add depth and complexity to your characters and make them more relatable to your readers.

You might want to weave these into your jealous character's backstory to build a more believable character:

Mental health issues such as anxiety or personality disorders

Lack of trust in others

Childhood experiences of neglect or lack of attention

Unresolved emotional issues or traumas

Cultural or societal influences that value possessiveness or competition

Fear of abandonment or rejection

Past experiences of betrayal or infidelity

Low self-esteem or self-worth

Insecurity about themselves or their relationships

You may be able to show jealousy through your character's attitudes:

Insecurity about one's worth or position

Fear of losing something or someone valuable

Self-doubt and self-criticism regarding one's ability to compete or succeed

Envy toward others' possessions, achievements, or relationships

Resentment toward those who seem to have advantages or privileges

Suspicion and paranoia of others' actions or intentions

Obsessive thoughts or behaviors related to the object of jealousy

Anger or hostility toward those who threaten the object of jealousy

Here are some ideas for things your jealous character may think or struggle with:

Difficulty trusting others, especially those who have relationships with the person or thing they are jealous of

Difficulty feeling happy for others' successes

Constantly comparing themselves to others and feeling inferior

Guilt and shame for their jealous thoughts and actions

The need for validation and reassurance from others to feel secure

Obsessive thoughts and behaviors regarding the person or thing they are jealous of

Fear of losing what they have to someone else

Feeling threatened by anyone who seems to pose a threat to their desired object or person

Insecurity and low self-esteem

Here are some ideas for emotions your jealous character may experience:

Possessiveness

Obsessiveness

Fear of loss

Inferiority complex

Here are some facial expressions your jealous character may exhibit:

Clenched teeth

Flared nostrils

Tightened jaw

Furrowed eyebrows

Sneering or curling upper lip

Tense or rigid facial muscles

Heavy sighs or grunts

Narrowed eyes

Intense or piercing gaze

Here is some body language your jealous character may exhibit:

Frowning or scowling

Glaring or staring

Clenched jaw

Tightened fists

Tense facial expression

Stiff posture

Crossed arms

Pacing or restlessness

Here are some behaviors your jealous character may exhibit.

Competing with others to prove their worth or superiority

Sabotaging the success or happiness of others due to envy

Becoming irrationally angry or upset when a partner talks to or spends time with someone of the opposite sex

Comparing themselves to others and feeling inadequate or inferior

Feeling possessive or controlling in relationships

Feeling resentment or bitterness toward someone who has something they desire or covet

Obsessively checking a partner's phone or social media accounts

Here are some ways that your jealous character may grow and evolve over time:

Acknowledging and accepting their jealousy as a flaw

Practicing empathy and putting themselves in other characters' shoes

Letting go of control and learning to trust others

Forgiving themselves and others for past mistakes and misunderstandings

Attempting to understand the root causes of their jealousy

Recognizing and celebrating others' successes instead of feeling threatened by them

Making amends and actively working to repair damaged relationships

Learning to communicate their feelings in a healthy way

Developing a sense of self-worth and confidence independent of others

Try to avoid writing stereotypical jealous characters like these examples:

Don't make the character jealous to the point where they become unsympathetic or unlikable to readers.

Avoid making the character resort to extreme or violent behavior due to their jealousy.

Avoid making the character jealous in every situation or toward every character.

Don't make the character jealous without a clear reason or motivation.

Don't make the character overly possessive or controlling.

Avoid making the jealous character one-dimensional or solely focused on their jealousy.

Here are some potential negatives of being jealous. Note: These are subjective, and some might also be seen as positives depending on the context.

Jealousy can lead to negative emotions, such as resentment, anger, and bitterness.

Jealousy can damage relationships and create a toxic environment.

Jealousy can lead to irrational behavior and poor decision-making.

Jealousy can cause individuals to become possessive and controlling.

Here are some potential positives of being jealous. Note: These are subjective, and some might also be seen as negatives depending on the context.

Can lead to open and honest communication about feelings and concerns

Provides motivation to improve oneself

Helps identify what one values and desires in a relationship or situation

Can be a sign of deep emotional attachment and care

Here are some potential expressions used by jealous characters:

"You're mine, not theirs."

"I don't want anyone else to have what we have."

"I don't like the way they look at you."

"You're hiding something from me."

"Why do they always get the attention?"

"I just want to know everything about your day."

"I can't believe you would do that to me."

"I saw you talking to them; what were you saying?"

"You're spending too much time with them."

Here are some ways that being jealous could affect your character's relationships:

They might try to isolate their partner from others, making it difficult for them to maintain other relationships.

They might become possessive and controlling, limiting their partner's freedom and social interactions.

They may become angry or upset when their partner spends time with friends or family without them.

They may constantly check their partner's phone or social media accounts for signs of infidelity.

They might become emotionally manipulative, using their jealousy to guilt their partner into doing what they want.

They may become physically or emotionally abusive in extreme cases of jealousy.

They may hold grudges or keep a scorecard of perceived wrongs, leading to resentment and further jealousy.

They might feel threatened by their partner's friendships with members of the opposite sex.

They might become suspicious or accusatory without cause, leading to arguments and tension in the relationship.

It's important to remember that jealousy is a complex emotion and can manifest differently in different people and relationships. If you or someone you know is struggling with jealousy in a relationship, seeking professional help is often the best course of action.

Humbert Humbert from Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Catherine Earnshaw from Wuthering Heights by Emily Bront ë

Amy Dunne from Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn

Jay Gatsby from The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Severus Snape from the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling

Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

Tom Buchanan from The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Iago from Othello by William Shakespeare

Heathcliff from Wuthering Heights by Emily Bront ë

Here are some writing exercises you might try for learning to write jealous characters:

Write a scene from the perspective of a character who is the object of jealousy. How do they perceive the jealous character's behavior toward them?

Put your character in a situation where they must confront their jealousy. How do they handle it? Do they overcome their envy, or does it consume them?

Think about a time when you felt jealous. What triggered the feeling? How did you react? Try to describe the physical and emotional sensations you experienced.

Consider the different ways jealousy can manifest itself. Is your character passive-aggressive or do they lash out? Do they become obsessive or withdrawn?

Write a scene where a character sees someone they envy succeed in something they themselves have failed at. How does the character react? Do they try to hide their jealousy or confront it head-on?

Create a character who is envious of someone close to them. What are they jealous of? How does this affect their behavior toward the other person?

Write like a bestselling author

Love writing? ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of your stories.

The most successful people in the world have coaches. Whatever your level of writing, ProWritingAid will help you achieve new heights. Exceptional writing depends on much more than just correct grammar. You need an editing tool that also highlights style issues and compares your writing to the best writers in your genre. ProWritingAid helps you find the best way to express your ideas.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Never struggle with Show-and-Tell again. Activate your free trial or subscribe to view the Emotion Thesaurus in its entirety, or visit the Table of Contents to explore unlocked entries.

HELPFUL TIP:

Definition:, physical signals and behaviors:, internal sensations:, mental responses:, cues of acute or long term jealousy:, may escalate to:, cues of suppressed jealousy:, may de-escalate to:, associated power verbs:.

- How to Write A Book

- How to Get Published

- Self-Publishing

- Writing Prompts

- Writing for a Living

- Common Writing Mistakes

- Advertise With Us

How To Tackle Jealousy In Creative Writing

- Common Submission Mistakes

- How To Stop Your Blog Becoming Boring

- The One Thing Every Successful Writer Has In Common

- How To Make Yourself Aware Of Publishing Scams

- Why Almost ALL Writers Make These Grammar Mistakes At Some Point

- 5 Tips For Authors On How To Deal With Rejection

- Top Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Novel

- How to Avoid Common New Writer Mistakes

- 10 Mistakes New Fiction Writers Make

There are many reasons why jealousy in creative writing rears its ugly head. Writing envy can be a real problem that stops you from getting on with the task in hand. When it's really bad, it can stop you from writing altogether.

There are many reasons writers don’t write. We procrastinate, worry, or seem to run out of things to say. However one reason that perhaps is less common than these is jealousy. Many writers suffer from writers envy, and when the green-eyed monster strikes we perhaps, at the time, don’t realise just how negative its effect can be. Envy is an unpleasant trait under any circumstances, but if we let writers envy consume us it can actually stop us writing altogether. So why will envy keep us from writing, and what can we do to change it?

Jealousy in creative writing -understanding why

The first step towards taking control of your jealous feelings and using them to your advantage is to understand why you feel that way in the first place. It is difficult to admit that you are feeling jealous - it is an ugly emotion. But if you can then you can start to understand what catalysed it in the first place. Jealousy usually springs from our own anxiety, and a sense of uncomfortableness in our own skin. We are jealous of others because we believe they have done better than us, so it is our own shortcomings that are the problem, rather than their success. Concentrating on our own goals, working on them and striving for our own success is far more productive then angrily moaning about someone who has already got there.

Accept it, and use it

If you catch yourself feeling jealous then explore it a little further. You are jealous of the success of one of your peers? OK that’s fine. Instead of beating yourself up about it and allowing it to slow you down, use it as motivation to do better, and learn from it. What did that person do to achieve their success, was it hard work or luck? If it was the latter you might just have to accept that some people do just get lucky. It is not ‘unfair’ it is just life - how about the hard work route? Believe it or not that works for people too! If you want it enough and have a positive attitude there is no reason why you shouldn't achieve all of your goals.

Be gracious

If you notice jealousy in creative writing and find yourself envious of someone else's achievements, congratulate them. You may secretly be thinking, ‘why them and not me?’ but going up and talking to that person might just answer that question. It is easy to create a false persona to fit around those we are jealous of, we tend not to like them for no other reason than they have achieved something that we also want to achieve. Making them into an actual human being by talking to them makes it harder to do this, and you may end up feeling genuinely happy for them after all.

Have no fear

People can end up rather afraid of their jealousy, which can mean they avoid situations where chances of feeling that way are high. You might find yourself suddenly too busy to go to that writers group you used to enjoy so much. You might even get yourself so worked up because of jealous emotions that you feel you may as well give up writing forever. Whatever you do, don’t let jealousy win.

The thing to remember is that jealousy happens to us all. You are not a bad person if you feel envious of someone else’s achievements, it means you have ambition. Just remember it is how you handle your jealousy that counts, so learn to live with it and use it, and if you can’t do that, then simply let it go.

So now you know about jealousy in creative writing and what to do about it, why not learn mroe about how to stop runing your writing by comparing it to others?

Get A Free Writer's Toolkit By Visiting https://writerslife.org/gid

About Ty Cohen

Related posts.

- How To Organize Your Writing Day How To Organize Your Writing Day

- Should You Kill Off A Character? Should You Kill Off A Character?

- Book Publishers To Submit To Without An Agent Book Publishers To Submit To Without An Agent

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Latest News

Want to learn how to organize your writing day? These...

- Posted March 31, 2022

Wondering whether you should kill off a character? Read on...

- Posted January 20, 2022

If you have got a new story idea, how do...

- Posted December 30, 2021

Know your readers better and you'll be able to write...

Self-Publishing shame is real. Yet it shouldn't be. Self-publishing has...

- Posted November 17, 2021

Writing a blog for your business is a useful way...

- Posted November 4, 2021

Write your novel faster with these useful tips! Writing a...

- Posted October 14, 2021

Stay Connected

Newsletter signup.

Want to learn how to organize your writing day?...

- March 31, 2022

Wondering whether you should kill off a character? Read...

- January 20, 2022

If you have got a new story idea, how...

- December 30, 2021

The hard truth of the matter is - not...

- May 6, 2016

A good writer is always looking for ways to...

- June 23, 2016

While some writers believe in writer's block and some...

- January 25, 2017

Not so long ago, the first hurdle for an...

- January 31, 2015

Grammar is a tricky beast. There are so many...

- March 4, 2016

"Share, Like or Tweet If You Love Writing" So...

This is a question that all writers, both aspiring...

- March 11, 2016

Every writer knows that one of the ways you...

- August 5, 2016

If you are hoping to have a long and...

- February 1, 2016

When creating any new piece of writing, selecting the tense...

- December 18, 2015

Facebook Site Visit Tracking

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

Writer's Life.org is the go to place for writers and authors across the planet and of all genres. Our mission is to give you the resources, tools and information needed to take your writing to the next level.

How do we plan on accomplishing this? Easy, instead of focusing 110% of our efforts on meaningless things such as correct spelling, proper grammar and fancy words...

...We'll give you solid information, that you'll get solid results with when tested in the real world ;-)

So with that said...

Consider the mis-spellings, grammatical mistakes and lack of $1000.00 words that you may or may not find on this site a reminder to you to focus on the things that will "really" prompt publishers to become interested in your book or potential fans of your writing to want more and more and more..

...And that is, learning how to write not good, but Great content, that pulls people in and will have them coming back begging for more. (Geesh... Could we get any worse with this run on sentence and lack of structure? I guess not, but I'm sure you get the point...)

A publishing house could care less if you won the spelling bee 10 years in a row.. They have editors that they pay to correct mistakes...

The only thing they are interested in is knowing if your writing is something that will SELL..

Nothing more, nothing less!

Consider this lesson #1 ;-) (Use the social buttons above to follow us on your favorite social site.. You'd hate to mis the next lesson wouldn't you?)

- Product Disclaimer

- Information Disclaimer

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Write for Writer’s Life

Copyright © WritersLife.org 2017-2022 All rights reserved.

Describing Sadness in Creative Writing: 33 Ways to Capture the Blues

By: Author Paul Jenkins

Posted on August 25, 2023

Categories Creative Writing , Writing

Describing sadness in creative writing can be a challenging task for any writer.

Sadness is an emotion that can be felt in different ways, and it’s important to be able to convey it in a way that is authentic and relatable to readers. Whether you’re writing a novel, short story, or even a poem, the ability to describe sadness can make or break a story.

Understanding sadness in writing is essential to creating a believable character or scene. Sadness is a complex emotion that can be caused by a variety of factors, such as loss, disappointment, or loneliness. It’s important to consider the context in which the sadness is occurring, as this can influence the way it is expressed.

By exploring the emotional spectrum of characters and the physical manifestations of sadness, writers can create a more authentic portrayal of the emotion.

In this article, we will explore the different ways to describe sadness in creative writing. We will discuss the emotional spectrum of characters, the physical manifestations of sadness, and the language and dialogue used to express it. We’ll also look at expert views on emotion and provide unique examples of describing sadness.

By the end of this article, you’ll have a better understanding of how to authentically convey sadness in your writing.

Key Takeaways

- Understanding the emotional spectrum of characters is essential to creating a believable portrayal of sadness.

- Physical manifestations of sadness can be used to convey the emotion in a more authentic way.

- Authenticity in describing sadness can be achieved through language and dialogue, as well as expert views on emotion.

33 Ways to Express Sadness in Creative Writing

Let’s start with some concrete examples of sadness metaphors and similes:

Here are 33 ways to express sadness in creative writing:

- A heavy sigh escaped her lips as a tear rolled down her cheek.

- His eyes glistened with unleashed tears that he quickly blinked away.

- Her heart felt like it was being squeezed by a cold, metal fist.

- A profound emptiness opened up inside him, threatening to swallow him whole.

- An avalanche of sorrow crashed over her without warning.

- His spirit sank like a stone in water.

- A dark cloud of grief descended on her.

- Waves of sadness washed over him, pulling him under.

- She felt like she was drowning in an ocean of melancholy.

- His eyes darkened with sadness like a gathering storm.

- Grief enveloped her like a wet blanket, heavy and smothering.

- The light in his eyes dimmed to a flicker behind tears.

- Sadness seeped through her veins like icy slush.

- The corners of his mouth drooped like a wilting flower.

- Her breath came in short, ragged gasps between sobs.

- A profound melancholy oozed from his pores.

- The weight of despair crushed her like a vice.

- A haunted, hollow look glazed over his eyes.

- An invisible hand squeezed her heart, wringing out all joy.

- His soul curdled like spoiled milk.

- A silent scream lodged in her throat.

- He was consumed by a fathomless gloom.

- Sorrow pulsed through her veins with every beat of her heart.

- Grief blanketed him like new-fallen snow, numbing and icy.

- Tears stung her eyes like shards of glass.

- A cold, dark abyss of sadness swallowed him.

- Melancholy seeped from her like rain from a leaky roof.

- His spirit shriveled and sank like a deflating balloon.

- A sick, hollow ache blossomed inside her.

- Rivulets of anguish trickled down his cheeks.

- Sadness smothered her like a poisonous fog.

- Gloom settled on his shoulders like a black shroud.

- Her sorrow poured out in a river of tears.

Understanding Sadness in Writing

Describing sadness in writing can be a challenging task.

Sadness is a complex emotion that can manifest in different ways. It can be expressed through tears, sighs, silence, or even a simple change in posture. As a writer, you need to be able to convey sadness effectively to your readers, while also avoiding cliches and melodrama.

One way to approach describing sadness is to focus on the physical sensations and reactions that accompany it. For example, you might describe the feeling of a lump in your throat, or the tightness in your chest. You could also describe the way your eyes become watery, or the way your hands tremble.

These physical descriptions can help your readers to empathize with your characters and feel the same emotions.

Another important aspect of describing sadness is the tone of your writing. You want to strike a balance between conveying the depth of the emotion and avoiding excessive sentimentality.

One way to achieve this is to use simple, direct language that conveys the emotion without resorting to flowery language or overwrought metaphors.

When describing sadness, it’s also important to consider the context in which it occurs. Sadness can be a response to many different situations, such as loss, disappointment, or rejection. It can also be accompanied by other emotions, such as anger, confusion, or melancholy.

By considering the context and accompanying emotions, you can create a more nuanced and realistic portrayal of sadness in your writing.

Finally, it can be helpful to draw on examples of how other writers have successfully described sadness. By studying the techniques and descriptions used by other writers, you can gain a better understanding of how to effectively convey sadness in your own writing.

In conclusion, describing sadness in writing requires a careful balance of physical descriptions, tone, context, and examples. By focusing on these elements, you can create a more nuanced and effective portrayal of this complex emotion.

Emotional Spectrum in Characters

In creative writing, it’s important to create characters that are multi-dimensional and have a wide range of emotions. When it comes to describing sadness, it’s essential to understand the emotional spectrum of characters and how they respond to different situations.

Characters can experience a variety of emotions, including love, happiness, surprise, anger, fear, nervousness, and more.

Each character has a unique personality that influences their emotional responses. For example, a protagonist might respond to sadness with a broken heart, dismay, or feeling desolate.

On the other hand, a character might respond with anger, contempt, or apathy.

When describing sadness, it’s important to consider the emotional response of the character. For example, a haunted character might respond to sadness with exhaustion or a sense of being drained. A crestfallen character might respond with a sense of defeat or disappointment.

It’s also important to consider how sadness affects the character’s personality. Some characters might become withdrawn or depressed, while others might become more emotional or volatile. When describing sadness, it’s important to show how it affects the character’s behavior and interactions with others.

Overall, the emotional spectrum of characters is an important aspect of creative writing. By understanding how characters respond to different emotions, you can create more realistic and relatable characters. When describing sadness, it’s important to consider the character’s emotional response, personality, and behavior.

Physical Manifestations of Sadness

When you’re feeling sad, it’s not just an emotion that you experience mentally. It can also manifest physically. Here are some physical manifestations of sadness that you can use in your creative writing to make your characters more believable.

Tears are one of the most common physical manifestations of sadness. When you’re feeling sad, your eyes may start to water, and tears may fall down your cheeks. Tears can be used to show that a character is feeling overwhelmed with emotion.

Crying is another physical manifestation of sadness. When you’re feeling sad, you may cry. Crying can be used to show that a character is feeling deeply hurt or upset.

Numbness is a physical sensation that can accompany sadness. When you’re feeling sad, you may feel emotionally numb. This can be used to show that a character is feeling disconnected from their emotions.

Facial Expressions

Facial expressions can also be used to show sadness. When you’re feeling sad, your face may droop, and your eyes may look downcast. This can be used to show that a character is feeling down or depressed.

Gestures can also be used to show sadness. When you’re feeling sad, you may slump your shoulders or hang your head. This can be used to show that a character is feeling defeated or hopeless.

Body Language

Body language can also be used to show sadness. When you’re feeling sad, you may cross your arms or hunch over. This can be used to show that a character is feeling closed off or defensive.

Cold and Heat

Sadness can also affect your body temperature. When you’re feeling sad, you may feel cold or hot. This can be used to show that a character is feeling uncomfortable or out of place.

Sobbing is another physical manifestation of sadness. When you’re feeling sad, you may sob uncontrollably. This can be used to show that a character is feeling overwhelmed with emotion.

Sweating is another physical manifestation of sadness. When you’re feeling sad, you may sweat profusely. This can be used to show that a character is feeling anxious or nervous.

By using these physical manifestations of sadness in your writing, you can make your characters more realistic and relatable. Remember to use them sparingly and only when they are relevant to the story.

Authenticity in Describing Sadness

When it comes to describing sadness in creative writing, authenticity is key. Readers can tell when an author is not being genuine, and it can make the story feel less impactful. In order to authentically describe sadness, it’s important to tap into your own emotions and experiences.

Think about a time when you felt truly sad. What did it feel like? What physical sensations did you experience? How did your thoughts and emotions change? By tapping into your own experiences, you can better convey the emotions of your characters.

It’s also important to remember that sadness can manifest in different ways for different people. Some people may cry, while others may become withdrawn or angry. By understanding the unique ways that sadness can present itself, you can create more authentic and realistic characters.

If you’re struggling to authentically describe sadness, consider talking to a loved one or best friend about their experiences. Hearing firsthand accounts can help you better understand the nuances of the emotion.

Ultimately, the key to authentically describing sadness is to approach it with empathy and understanding. By putting yourself in the shoes of your characters and readers, you can create a powerful and impactful story that resonates with your audience.

Language and Dialogue in Expressing Sadness

When writing about sadness, the language you use can make a big difference in how your readers will perceive the emotions of your characters.

Consider using metaphors and similes to create vivid images that will help your readers connect with the emotions of your characters.

For example, you might describe the sadness as a heavy weight on the character’s chest or a dark cloud hanging over their head.

In addition to using metaphors, you can also use adjectives to describe the character’s emotions. Be careful not to overuse adjectives, as this can detract from the impact of your writing. Instead, choose a few powerful adjectives that will help your readers understand the depth of the character’s sadness.

For example, you might describe the sadness as overwhelming, suffocating, or unbearable.

When it comes to dialogue, it’s important to remember that people don’t always express their emotions directly. In fact, sometimes what isn’t said is just as important as what is said.

Consider using subtext to convey the character’s sadness indirectly. For example, a character might say “I’m fine,” when in reality they are struggling with intense sadness.

Another way to use dialogue to convey sadness is through the use of behaviors. For example, a character might withdraw from social situations, stop eating or sleeping properly, or engage in self-destructive behaviors as a result of their sadness.

By showing these behaviors, you can help your readers understand the depth of the character’s emotions.

Finally, when describing sadness, it’s important to consider the overall mood of the scene. Use sensory details to create a somber atmosphere that will help your readers connect with the emotions of your characters.

For example, you might describe the rain falling heavily outside, the silence of an empty room, or the dim lighting of a funeral home.

Overall, when writing about sadness, it’s important to choose your words carefully and use a variety of techniques to convey the depth of your character’s emotions.

By using metaphors, adjectives, dialogue, behaviors, and sensory details, you can create a powerful and emotionally resonant story that will stay with your readers long after they’ve finished reading.

Expert Views on Emotion

When it comes to writing about emotions, it’s important to have a deep understanding of how they work and how they can be conveyed effectively through writing. Here are some expert views on emotion that can help you write about sadness in a more effective and engaging way.

Dr. Paul Ekman

Dr. Paul Ekman is a renowned psychologist who has spent decades studying emotions and their expressions. According to Dr. Ekman, there are six basic emotions that are universally recognized across cultures: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust.

When it comes to writing about sadness, Dr. Ekman suggests focusing on the physical sensations that accompany the emotion.

For example, you might describe the heaviness in your chest, the lump in your throat, or the tears that well up in your eyes. By focusing on these physical sensations, you can help your readers connect with the emotion on a deeper level.

While sadness is often seen as a “negative” emotion, it’s important to remember that all emotions have their place in creative writing. Disgust, for example, can be a powerful tool for conveying a character’s revulsion or aversion to something.

When writing about disgust, it’s important to be specific about what is causing the emotion. For example, you might describe the smell of rotting garbage, the sight of maggots wriggling in a pile of food, or the texture of slimy, raw meat.

By being specific, you can help your readers feel the full force of the emotion and understand why your character is feeling it.

Overall, when it comes to writing about emotions, it’s important to be both specific and authentic. By drawing on your own experiences and using concrete details to describe the physical sensations and causes of emotions, you can create a more engaging and emotionally resonant piece of writing.

Unique Examples of Describing Sadness

When it comes to describing sadness in creative writing, there are many unique ways to convey this emotion to your readers. Here are some examples that can help you create a powerful and moving scene:

- The crying scene : One of the most common ways to show sadness is through tears. However, instead of just saying “she cried,” try to describe the crying scene in detail. For instance, you could describe how her tears fell like raindrops on the floor, or how her sobs shook her body like a violent storm. This will help your readers visualize the scene and feel the character’s pain.

- The socks : Another way to show sadness is through symbolism. For example, you could describe how the character is wearing mismatched socks, which represents how her life is falling apart and nothing seems to fit together anymore. This can be a subtle yet effective way to convey sadness without being too obvious.

- John : If your character is named John, you can use his name to create a sense of melancholy. For example, you could describe how the raindrops fell on John’s shoulders, weighing him down like the burdens of his life. This can be a creative way to convey sadness while also adding depth to your character.

Remember, when describing sadness in creative writing, it’s important to be specific and use vivid language. This will help your readers connect with your character on a deeper level and feel their pain.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some effective ways to describe a person’s sadness without using the word ‘sad’.

When describing sadness, it’s important to avoid using the word “sad” as it can come across as cliché and lackluster. Instead, try using more descriptive words that evoke a sense of sadness in the reader. For example, you could use words like “heartbroken,” “bereft,” “devastated,” “despondent,” or “forlorn.” These words help to create a more vivid and emotional description of sadness that readers can connect with.

How can you describe the physical manifestations of sadness on a person’s face?

When describing the physical manifestations of sadness on a person’s face, it’s important to pay attention to the small details. For example, you could describe the way their eyes become red and swollen from crying, or how their mouth trembles as they try to hold back tears. You could also describe the way their shoulders slump or how they withdraw into themselves. By focusing on these small but telling details, you can create a more realistic and relatable portrayal of sadness.

What are some examples of using metaphor and simile to convey sadness in creative writing?

Metaphors and similes can be powerful tools for conveying sadness in creative writing. For example, you could compare a person’s sadness to a heavy weight that they’re carrying on their shoulders, or to a storm cloud that follows them wherever they go. You could also use metaphors and similes to describe the way sadness feels, such as a “gnawing ache” in the pit of their stomach or a “cold, empty void” inside their chest.

How can you effectively convey the emotional weight of sadness through dialogue?

When writing dialogue for a character who is experiencing sadness, it’s important to focus on the emotions and feelings that they’re experiencing. Use short, simple sentences to convey the character’s sadness, and avoid using overly complex language or metaphors. You could also use pauses and silences to create a sense of emotional weight and tension in the scene.

What are some techniques for describing a character’s inner sadness in a way that is relatable to the reader?

One effective technique for describing a character’s inner sadness is to focus on their thoughts and feelings. Use introspection to delve into the character’s emotions and describe how they’re feeling in a way that is relatable to the reader. You could also use flashbacks or memories to show why the character is feeling sad, and how it’s affecting their current actions and decisions.

How can you use sensory language to create a vivid portrayal of sadness in a poem or story?

Sensory language is an effective way to create a vivid portrayal of sadness in a poem or story. Use descriptive words that evoke the senses, such as the smell of rain on a sad day or the sound of a distant train whistle. You could also use sensory language to describe the physical sensations of sadness, such as the weight of a heavy heart or the taste of tears on the tongue. By using sensory language, you can create a more immersive and emotional reading experience for your audience.

Need help submitting your writing to literary journals or book publishers/literary agents? Click here! →

Jealousy And Writers: Tips To Beat The Green-Eyed Monster

by Writer's Relief Staff | The Writing Life | 15 comments

Review Board is now open! Submit your Short Prose, Poetry, and Book today!

Deadline: thursday, april 18th.

In Natalie Merchant’s 1995 song “Jealousy,” a woman asks these questions about a rival for her lover’s affections: “Is she bright/so well read/are there novels/by her bed?”

The singer might have been even more jealous if those bedside novels were written by her rival. Jealousy and envy are common emotions for writers. When someone you know becomes a successful and well-published writer, envy can be inevitable. And when megacelebrities who never paid their writing dues get big book deals for novels and memoirs that they didn’t actually write, the envy can become…unenviable.

So how will you, as a creative writer, react when confronted with the green-eyed monster? You could become a jealous maniac (like one of the 10,000 Maniacs, the band Ms. Merchant fronted before going solo). But we at Writer’s Relief know you have to be realistic, so here are six practical tips for turning envy into empowerment.

How To Deal With Jealousy In The Writing Life

1. Use your jealousy as motivation. If a friend or member of your writing group gets a poem or short story accepted by a prestigious literary journal , cultivate an “I can do that too” attitude. If that person can get an acceptance letter, you can too!

2. Congratulate the person on her or his publishing accomplishment. Being gracious is the right thing to do. It will make you feel better to know you reacted well. And staying on good terms with the worthy wordsmith might eventually pay dividends, which leads to our third point:

3. Rather than stewing in jealousy, ask a successful writer for help! Turn a negative experience into a positive one. Often, honest communication can help alleviate jealous thoughts.

4. That’s why it’s important to talk things out. Confide in a close friend or spouse. Don’t keep jealousy all bottled up. And also, when your kind friend reminds you of all the reasons you shouldn’t be jealous, be open to hearing—really hearing—the words.

5. Don’t be afraid of jealousy. If being uncomfortable with jealousy makes you avoid writing groups and writers conferences , you’re not doing yourself any favors. Push through jealousy. Accept it, then either find a way to use it as a motivator OR let it go.

6. Take appropriate action when celebrities get lucrative book deals. If you’re jealous of notables such as politicians, musicians, and actors reaching publishing nirvana (often with ghostwriting or cowriting help) while you struggle, vote for their opponents, avoid their overpriced concerts, and ignore their TV shows and films. They’ll be devastated.

Well, okay, maybe not…but you’ll feel better, anyway!

Finally, don’t forget that when Natalie Merchant left 10,000 Maniacs for a successful solo career, the remaining group members eschewed envy, plugged along, and eventually recorded a top-40 hit (with new lead singer Mary Ramsey). Jealousy can be a negative influence—or just another stepping-stone on the path to better things. Ultimately, it’s up to you!

15 Comments

This reminds me of what legendary writer Pete Hamill told me in a 1978 interview, “You emulate, you imitate, you equal, and you surpass.”

This article hits very close to home. My friend Rod Moore is coming into town next week. Rod and I spent a year together in a fiction writing master’s program at U.C. Davis way back in 1975; Rod was the most lionized student in the program, because he’d started publishing even as an undergraduate, and had an impressive, ornate, Jamesian writing style. The next year, I got into Columbia’s writing program, so headed to NYC and earned my MFA two years later, while Rod stayed at Davis and finished his MFA there. Now, about 35 years later, Rod has managed to continue writing fiction, quite successfully, winning the prestigious Iowa short story collection annual award a few years ago and now just coming off a stint at the fabulous MacDowell writers colony. Meanwhile, I published one piece of fiction in 1978, and none since. I write fiction infrequently and desultorily now, in fact read it infrequently as well, though the desire to write short stories and novels still beats deep within me — life with all its problems, financial difficulties, family, tennis, crosswords, and other kinds of writing (I’m a medical editor and sometimes magazine freelancer) have taken over. So, it’s a wee bit difficult to see Rod’s success in the field where I wanted success. However, Rod has earned it–he’s continued to plug away, and has reaped the rewards. He’s not rich because of it, he has to make his living as a teacher, but he has continued to write fiction, while I have not. It’s my own damn fault. So Rod, my hat’s off to you, man, for your due diligence and confidence and talent. Continued success, my friend. And after all, I ain’t dead yet — if I want to write fiction, all I have to do is write it.And hopefully I will. Hopefully Rod has set an example for me that I can one day follow. Hopefully sooner than later, because I ain’t gettin’ any younger. Rod, see you soon, buddy.

Great piece — fearlessly deals with a troublesome emotion. “Don’t be afraid of jealousy!” Amen! My further thought on the matter, something that helps me deal with both jealousy and disappointment, is that “success” in the form of publication, prizes, etc. is only the tip of the iceberg. Developing as a writer and truth-teller is a lifelong process and you will run the emotional gamut as you pursue it. The deeper issues are craftsmanship and the hidden truths of being alive. Success ebbs and flows, and comes to everyone who sticks with something — AND is always temporary. But deep feelings between and among writers based on a common search for personal and universal truths is not capricious. When you connect with other writers at that level, their success is your success, and vice versa.

I can’t help responding to this even though I’m supposed to be writing….Back in 1976 I was an English lit major at Worcester State College. One day my poetry professor announced that one of his best friends not only had a couple of book deals, but had a movie deal as well. The book? Salem’s Lot! Now there’s a reason to be jealous. Though — in that very book one can find the secret to the author’s success. One of the tenants at the hotel where the protagonist is staying complains about the typewriter noise. “He starts at 9 am and goes until noon. Then he starts again at 3 pm and goes until 6. Then he begins at 9 until midnight.”(I’m paraphrasing of course) Even writing every day, how many of us can claim to work that hard?

Alyne, thank you for sharing this story with us! And you do make a very good point. Talent and vision are so important, but many writers get sidetracked and don’t devote the kind of butt-in-chair time that success requires.

I recently had a friend get published. At first I was jealous; then I started helping him sell books. It shouldn’t be all about getting published; it is just as important to see your friends succeed.

Great article. I’d also like to add to try not to think of everyone as being a direct competitor. You only compete against yourself. Other people’s successes spur me on to try harder, and then there are times when I have to admit I will never be Toni Morrison. But it’s a big world and there’s room for all of us.

Perfectly explained Suzette. I feel the same. There is a place for every writer somewhere in this world. We all make a mark only that the depth of the mark makes us popular and not so popular.

I’ve often found my jealousy to be misplaced, whether related to someone’s job, life situation, or perceived success (i.e. thinking someone makes sooooo much money when they really don’t, or blowing a supposed big break out of proportion). It is so easy to sulk because my friends are living in great cities and getting fabulous jobs two years out of school – but the superficial details never tell the whole story. And when I worry about those issues I am simply projecting my own insecurities onto other people and taking my focus away from my own issues.

Easy enough to say now. We’ll see what happens when I go to grad school.

I find when I get jealous at other writers’ successes I write myself. So I that is a kind of motivation to get off my rear.

Great article! The irony…I found it when I googled “dealing with envy” after reading of a bloggers (whom I hardly know!) newfound success with a book deal! I won’t go on and on with excuses about my lack of time (while a stay at home mom with two small children)…some people wouldn’t “get it” anyway…I need to use what I have, where I am to do the best I can…some great comments!

Lisa, we’re glad you found us and enjoyed our article. Thanks for commenting!

Wow! I’m just finding this but I’m so glad I did! I haven’t found myself directly envious of anyone yet, but my mind keeps poking me with that “what if” moment. What if a family member succeeds where I have yet to? Or a writer-friend? Sometimes it’s so intense that I refuse to speak about my writing, except to say that, yes I am a writer. I’ve been working on handling this though. Not, getting rid of the envy. It pushes me to put “butt in chair.” 🙂 So, I kinda like it – to an extent. 🙂 Thanks so much for sharing …

I smiled when I read the headline of this article, because it reminded me of a PBS show (“American Masters”) that I’d just seen on Harper Lee — whose friendship with Truman Capote cooled when her novel (To Kill A Mockingbird) won the Pulitzer Prize, and his book (In Cold Blood) didn’t. The irony, of course, was that he called on her to help him with it.

In light of that situation, I’d question tip #1 — because neither of them finished another book. So jealousy may not be such a great motivator after all.

Then again, your example is not the best one, since the ex-Maniacs recruited a lead singer who sounded much like her departed predecessor. While that factor enables them to make a living, in pure commercial terms, Natalie Merchant’s name will always be the bigger draw.

A better example of tip #1 is the Clash’s ex-guitarist, Mick Jones, who put his own groundbreaking outfit (Big Audio Dynamite) together right after they kicked him out in 1983. Mick enjoyed a high degree of success through the ’80s and early ’90s — while his ex-partner, Joe Strummer, spent much of that time struggling to find his creative footing again.

OK, enough rock ‘n’ roll history lessons — one other comment I’d make is that beating the green-eyed monster is often far easier said than done…all too often, folks seem willing to trample their grandmother in a heartbeat when those big prizes (status, money, fame, etc.) seem within reach.

I speak from experience: back in college, I wrote for several fanzines, including one started by a guy who decided to found his own “proper” literary magazine (as in, glossy paper vs. photocopy). However, when I — and some others who’d written for the former rag — checked out the possibility of being involved with the new publication, we were blown off, rebuffed, and treated in a pretty unpleasant manner. My blowback got more intense, because I called the guy out (and got a fairly nasty letter back).

The overall impression left was one of being “traded in” for a new circle of local heroes that (presumably) would be used to burnish the guy’s reputation (as well as his new project).

In some respects, this is neither here or there, because the new project ran out of steam after one or two issues (I think), and the guy moved on to other things. I didn’t talk to him at length again (other than a couple of quick encounters in public spaces).

So, I enjoyed reading your article, but I do think we need to qualify a few things — I don’t think anybody really begrudges the Stephen Kings of the world, because he’d have been discovered somewhere along the line.

If people get riled up, it’s more likely to happen in low-rent situations like the one I’ve described — or, as a friend of mine reminded me recently, “entering contests where the favored local writer always seemed to win.”

So it’s not realistic (per tip #2) to expect folks to say “congrats” in every instance: relationships often get soured or trampled in the “chase” for the prizes, making it difficult for the parties to get past that point again.

You live and learn, and chalk all it up to experience — that’s why Dave Mustaine, of Megadeth, has gone on record admitting that he shouldn’t have burned so much energy on trying to scale the same mega-heights as Metallica, after they booted him out early in their career.

If there’s a moral here, it might well be: stand on your own, if you can…and let the chase take care of itself.

I am a writer with steady writing success, and can’t seem to escape the jealousy, no matter what group I join, or writer I hang out with. My whole opinion of writing jealous is that it comes from feeling the need to support your ego and prove something to other people. I knew diagnosed narcissists who couldn’t stop being jealous of other people’s success. I am a firm believer that people who focus on striving for excellence, and willing to get writing education, shouldn’t get jealous. I know writers who are jealous of other writers, yet barely seenlm comfortable with getting critique, and don’t have a history of having writing education. I also think when other writers get jealous, it is because they are too focused on competition, rather than personal growth. I have got pushed out of groups (even those I paid to be in) simply because of excellence in my work, and success. If you mention your writing success then you are arrogant, if you repeatedly share excellent work, then you are showing off…etc. Once you become a great writer that’s achieved, it’s like you got to watch you back, and go into hiding, and never speak of it. I keep to myself now, and don’t bother joining writing forums or critique groups anymore, nor expect to have any real writing friends.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

See ALL the services we offer, from FREE to Full Service!

Click here for a Writer’s Relief Full Service Overview

Services Catalog

Free Publishing Leads and Tips!

- Name * First Name

- Email * Enter Email Confirm Email

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Featured Video

- Facebook 121k Followers

- Twitter 113.9k Followers

- YouTube 5.1k Followers

- Instagram 5.5k Followers

- LinkedIn 146.2k Followers

- Pinterest 33.5k Followers

- Name * First

- E-mail * Enter Email Confirm Email

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

WHY? Because our insider know-how has helped writers get over 18,000 acceptances.

- BEST (and proven) submission tips

- Hot publishing leads

- Calls to submit

- Contest alerts

- Notification of industry changes

- And much more!

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Pin It on Pinterest

How to write Jealousy into your Romance Novel

Jealousy, an inherent part of the human psyche, is something everyone relates to, which is why it’s a common theme in romance novels. You can use it to establish your characters’ desires and show how important those desires are to the characters. Jealousy generates conflict and gives depth to the people in your book. It can define who those people are by how they react to the emotion. Incorporating jealousy also evokes reader sympathy and empathy because everyone knows what it’s like to feel jealous. It’s not a fun feeling, and readers relate to characters through the unsavory emotion.

Examples of Jealousy in Romance

There are many types of jealousy that are generated by different scenarios. For example, you could have romantic jealousy or possessive jealousy, professional jealousy between coworkers or familial jealousy between siblings. You could even have extreme jealousy, when one character goes to extremes to resolve their feelings.

Romantic Jealousy

Edward and Jacob both exhibit their romantic jealousy in Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight Saga as they butt heads over loving the same girl, Bella. This creates conflict and gives the readers insight into the depth of their love.

Possessive Jealousy

In The Mortal Instruments series, by Cassandra Clare, Simon’s jealousy of Jace is somewhat similar in this regard, though Jace is less concerned over Clary’s friendship with Simon. And as the story unfolds, Simon’s jealousy transforms more into the category of a possessive jealousy. While he has feelings for Clary, his jealousy stems from his fear of losing her as a friend, both to Jace, who she has a crush on, but also to the world of shadowhunters.

Evolving Jealousy

The Hating Game , written by Sally Thorne, illicites a more professional undertone to jealousy as Lucy and Joshua struggle to earn the same promotion. Her fresh take on a workplace romance generates jealousy between the two love interests before they discover that their conflict may be based in sexual tension just as much as it is in jealousy.

Familial Jealousy

Of course, everyone is familiar with familial and friendly competition. This generates jealousy between siblings or two best friends and challenges the characters to rise above their baser emotions to protect their love for each other. East of Eden , by John Steinbeck, is a perfect example of two half-brothers, Adam and Charles, who regard each other as competition as they both vie for the same girl’s affections.

Rivals can stem from jealousy as well. Take Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs . In this timeless classic, the queen, and stepmother, grows jealous of Snow White’s beauty and how all around her love the younger girl. Their conflict escalates as the queen instructs a hunter to take Snow White to the woods and kill her to remove the girl as a rival for people’s love.

Extreme Jealousy

Then there’s extreme jealousy. In Nicholas Sparks’s Safe Haven , Erin’s abusive husband, Kevin, hunts her down and tries to kill her and her new love interest, Alex, when he finds her and sees she’s moved on. This jealousy borders on psychotic as he chooses to kill the one he loves rather than let her leave him.

How do you write it into your own novel?

Each of these forms of jealousy drives the plot forward and adds depth to the characters. But how do you develop your own character’s jealousy?

Analyze character motives

Start by analyzing what fuels their jealousy: fear, insecurity, rejection, confusion, distrust, shame, paranoia, envy. These underlying emotions give motive to your characters and strengthen their personalities. Jealousy just for jealousy’s sake can quickly be resolved, but what about jealousy that stems from the fear of not being good enough? Jealousy formed because the lover doesn’t trust their love interest after being cheated on will be more engaging than jealousy with no reason behind it.

Paint a jealous picture