- How to Cite

- Language & Lit

- Rhyme & Rhythm

- The Rewrite

- Search Glass

How to Write a Narrative about Another Person (3-Paragraphs)

In a previous article, I wrote, "my main objective is to help people understand that writing a narrative is very important for the individual writer and for the audience who reads the writer's narratives. Writing a narrative allows each individual to explore his or her own inner self and come to a self- realization or epiphany about his/her life. It is my believe that the narrative allows each individual writer to re-live a fragment of his/her past life or past beliefs, which results in a responsible acceptance of that past so that one can move forward with higher character, higher self-esteem, and higher knowledge." Having stressed this point, I would love for my readers to understand that the above belief does not only apply to writing about your own self. The above statement also applies to writing about someone you know. Writing about someone you know allows the writer to share the lessons learned from that other person; it allows the writer to preserve a very important memory of that person; it allows the writer to show other readers the importance of preserving the memories of loved ones and the people who touch our lives. Finally, it allows the writer to share with the readers that one person can absolutely play a major role in shaping our own individual lives and beliefs.

As I mentioned in a previous article, "The first step is to find your own time and personal space. Allow all worries from your day, your past, your future to be set aside. One way to allow this to be possible is to take about ten minutes and meditate. Simply breathe in and breathe out, and relax. Allow this breathing to tranquilize all racing thoughts and help you focus on the now, the present moment. When you breathe in and out, try to picture yourself in a place where you find nothing but peace of mind." While breathing in and out, try to picture that one person who you are writing about. Picture all the positive things this person taught to you and passed on to you, and then write-write what you know about this person, so that he/she can live forever in memory. In step 2-4, follow the format of writing about this person in three paragraphs. In each step, I also provide an example of each paragraph. The three sample paragraphs are all one story. In step 5-6, I provide one more student sample of a three body paragraph narration that follows the format in step 2-4.

I. Introduction: First paragraph

a. Have a clear topic sentence that states who the inspiring person of your story is and include an adjective that best describes why this person is inspiring to you.

b. In about 5-6 sentences tell what your main point is. In short, tell the reader why this person is inspiring and how this person has inspired you to make a change for the better.

c. In about one sentence tell about one incident that this person went through that proved he or she was inspiring.

Sample of introduction: The lower case letters are to show my reader how all the ingredents from the format piece togther in the actual paragraphs,

(a)My Grandfather is the most inspiring person in my life because he is determined to never lose his culture. (b)I was born in America and my parents were born in America, but my grandfather was born in China. Since I was born in America, I have been raised with American values, which mostly means freedom of choice and that freedom of choice has never really allowed me to experience my own traditional culture. I have no accent, I did not speak Chinese, and I really knew nothing about my Chinese heritage. Heck my family and I usually eat hot dogs and hamburgers. However, my grandfather has always maintained his sense of being Chinese, and through him, I was able to understand that I am Chinese American. I am proud of both. (c) My grandfather came to America as a result of the Japanese invasion in China, and my grandfather lived to tell me his story, which has allowed me to know where I come from.

II. Body paragraph: Second paragraph

a. In about 8-10 sentences, tell the story about this inspiring person. Keep in mind that this life story should only be a fragment or fragments of a time that demonstrated how this person was inspiring to you. (DO NOT TELL EVERY DETAIL, SUCH AS BIRTH TO OLD AGE). Try to pick one element, such as a struggle that this individual went through and overcame.

b. In about one or two sentences tell how this person's event or episode ended.

Sample of Body Paragraph:

(a)My grandfather always gave me dirty looks or spoke to me coldly, and I never understood why. One day I asked him why, and that is when he sat down to tell me his story. My grandfather was born in China to a family of farmers. Life for him and his parents were simple. They worked the land and provided for small villages and towns, and that was their life. His mother was a traditional Chinese woman who took care of the men, and his father was a hard working farmer. His mother taught my grandfather about foods, clothing, domestic values, etc, while his father taught him about the value of hard work and the history of his people. However, one day a storm came and destroyed the land, and his family lost everything, after months of poverty, the Japanese invasion occurred. My grandfather lost both of his parents in the war, and at the age of 18, he came to America. In America, my grandfather lived in San Francisco, where he adapted to the English language, he became a Christian, and he settled for any type of work that he could find. Throughout these hardships of adapting, one can easily lose their culture, especially if a culture is not number one on the list; however, my grandfather married a beautiful and good Chinese girl, and they worked hard, started a family, opened up a successful Chinese restaurant and raised my parents in America. My grandfather and his wife raised my parents to speak Chinese and English, and kept Chinese tradition through stories of their past and traditional Chinese foods. However, when my parents had me, something along the way was lost, and I was raised fully American. (b)It was my grandfather's story of his life and past history that made me realize what I was missing, and now I know.

III. Conclusion: Third Paragraph

a. In about 2-3 sentences re-cap who this inspiring person is and why they inspired you.

b. In about 2-3 more sentences tell what change(s) you have made in your life or lesson that you have learned in your life as a result of this person.

c. In about one sentence, offer your reader some sort of advice or inspiring words about the person you know or about how people should never take for granted the ones who can truly touch and change another life for the better. Simply, end with the lesson that was learned and/or with a wise message to leave your reader with.

Sample of conclusion:

(a) My Grandfather inspired me because through all his hardships and cultural differences of moving to America from China, he never once forgot who he was or where he came from. He kept his language, his history, and his memories, while learning and starting a new history. He lived to tell his story to the third generation of Chinese American grand children, and because of his doing so, I now know that I am not American, but Chinese American, and I am proud of both. (b)As a result, I have now learned the Chinese language and all about my history so that I can pass that on to the fourth and fifth generations of my family. My grandfather only spoke to me coldly and gave me dirty looks because he was afraid that the tradition of who he is would end with me, but he no longer needs to have that fear. (c)It is important to know where you come from.

Another student sample of introduction:

(a) My mother is the most inspiring person to me because she is emotionally strong. Throughout my entire life, my mother never gave up on my sister and me.

(b) My mother raised us both and never once turned her back on us; she was there for us, and despite the fact that she may have been lonely raising us by herself, she remained strong and never let any other influences or desires take her away from us. My mother devoted her entire life to my sister and me. When my parents got divorced, my father abandoned all of us for another woman, and though my mom was left alone with us kids, she raised my sister and me.

(c) As a result, her strength turned my weakness into a threshold of endless desire to never give up.

Another student sample of body paragraph:

(a)I will never forget the day that turned many years into trial and tribulation. My parents got divorced. Our happy home of four was turned upside down. One day my mother came home to discover that my father was having an affair, not just an affair but a relationship, with another woman. When my parents divorced, my father decided he did not want us or to leave us with anything. So my mother raised my sister and me by herself. She spent days, weeks, months, and years trying to keep a roof over our heads; while still instilling proper values into my sister and me. My mother moved from a nice home to a small duplex with us. Everything in this duplex was falling apart and rotting, and while I began to lose hope of never finding happiness again, my mother maintained that hope. One day our roof caved in, and we did not have the money to fix it. Although my mom must have been scared and desperate, she did not do what I have seen many other parents do. She did not run away with another person; she did not turn to drugs or alcohol; she did not yell at me or my sister. Instead she just laughed and said, "I never did mind the little things." So she got an extra job and encouraged my sister and me to get a part-time job, and then we were able to fix the roof. (c)Through all these years of little hardships, my mother was able to save money, and now she runs her own business of a nonprofit organization of debt counseling service for people who are financially struggling.

Another student sample of conclusion:

(a) My mother is truly an inspiring person to me. Divorce can really cause a kid to lose his or her way, mostly from the self blame.

(b) As a result to this self-blame, I became a not so good teen. I hung out with the wrong crowds, I began drinking and smoking and failing classes. I brought this home to our duplex, but my mom never gave up; she felt alone, but she never gave up. The fact that she worked to keep my sister and me from losing hope, and she took her own hope and opened up a business to help people who experience much of the same suffering that made me realize all she sacrificed for us. After that one moment of her raising us out of the dirt, I changed. I am now in college studying English to become a professor and help people.

(c) It is important to always see the good in a bad time, and my mother was and is that good in what was once a bad time.

Edit your work until you know that your whole mind, heart, and soul is content and went into your narrative.

- Just simple follow the format, enjoy your writing experience, be creative, and find your voice through words.

This article was written by the CareerTrend team, copy edited and fact checked through a multi-point auditing system, in efforts to ensure our readers only receive the best information. To submit your questions or ideas, or to simply learn more about CareerTrend, contact us [here](http://careertrend.com/about-us).

How to Write an Essay about a Person

In this tutorial you will learn how to write a biographical essay – an essay about a person.

This method will work for writing about anyone:

- Your friend or a loved one

- A public or historical figure

- Anyone else you respect and admire.

How to Structure a Biographical Essay

The biggest challenge in writing a biography essay is coming up with material. And the easiest way to keep your ideas flowing is to break your topic into subtopics.

Do you recall the saying, “Divide and conquer?” This military concept states that in order to conquer a nation, you must divide it first.

We’ll use this idea in our approach to writing about a person. Remember, a person, a human being is our main subject in a biographical essay.

And to discuss a person effectively, we must “divide” him or her.

How would we go about dividing our subject into subtopics?

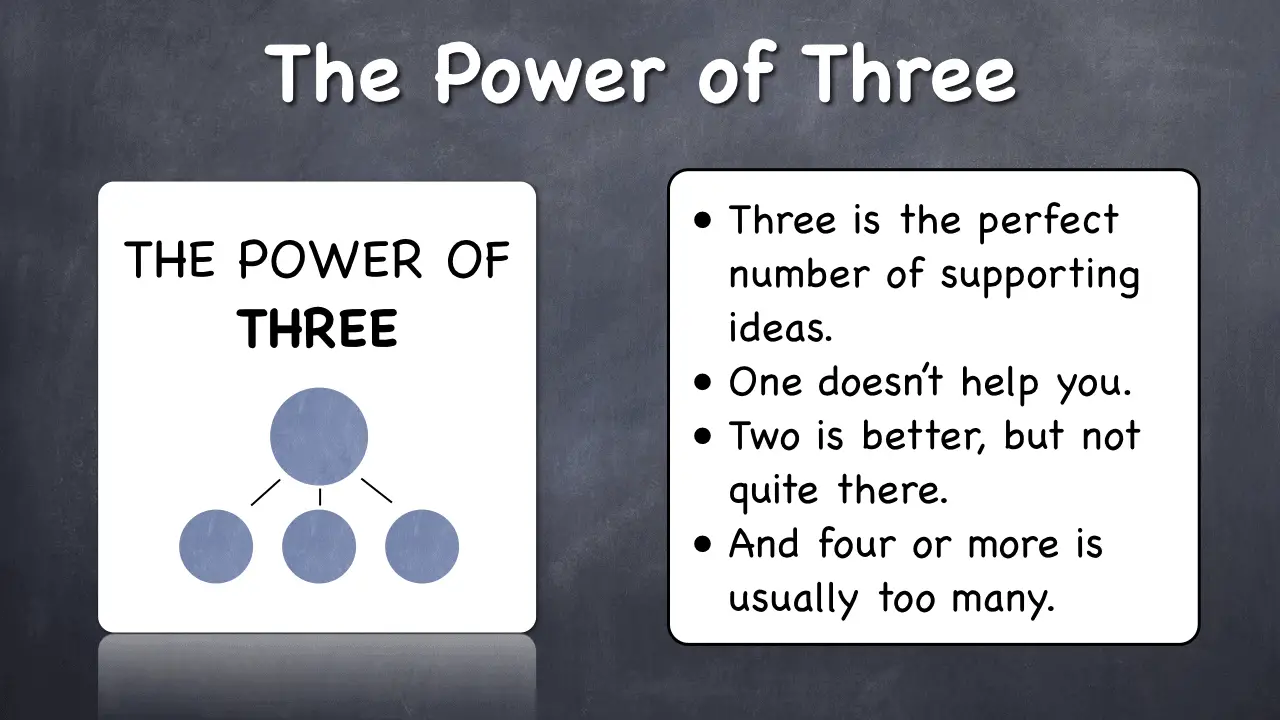

The Power of Three

The easiest way to break up any subject or any topic is to use the Power of Three.

When you have just one subject, undivided, that’s a recipe for being stuck. Dividing into two is progress.

But three main supporting ideas, which correspond to three main sections of your essay, are the perfect number that always works.

Note that the three supporting points should also be reflected in your thesis statement .

Let’s see how it would work when talking about a person.

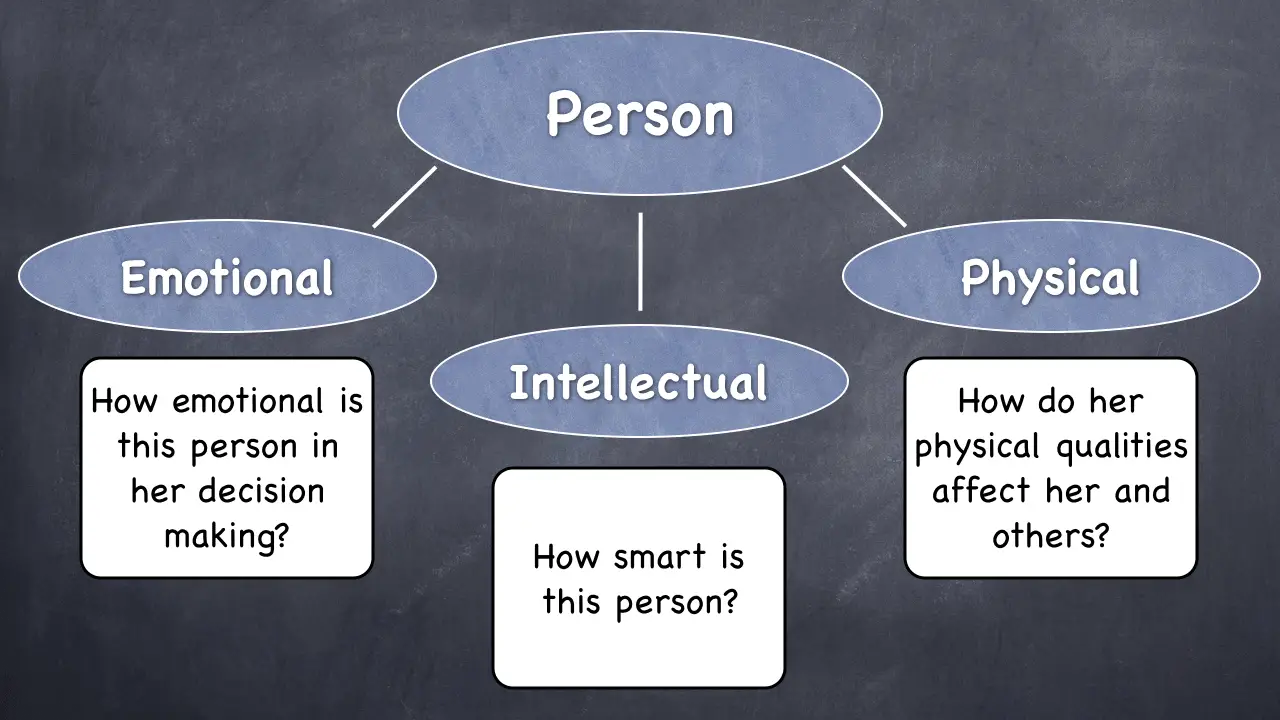

What does any person have? What are the aspects of any human being?

Any person has emotions.

In fact, humans are very emotional creatures. This part deals with how the person feels.

This section or part of the essay will answer some of the following questions:

“How emotional is this person in her decision making?”

“What emotions predominate in this person? Is this person predominantly positive or negative? Calm or passionate?”

You can discuss more than one emotion with regards to this person.

Any person has an intellect.

The intellect is the ability to think rather than feel. This is an important difference.

Something that is very important to remember when dividing your topic into subtopics is to make sure that each subtopic is different from the others.

Thinking is definitely different from feeling , although they are related because they are both parts of human psychology.

This part of the essay will answer the questions:

“How smart is this person?”

“How is this person’s decision making affected by her intellect or logic?”

“What intellectual endeavors does this person pursue?”

Any person has a body, a physicality.

This sounds obvious, but this is an important aspect of any human being about whom you choose to write.

This part of your essay answers these questions:

“What are this person’s physical attributes or qualities?”

“How do this person’s physical qualities affect her and others?”

“How do they affect her life?”

“Is this person primarily healthy or not?”

And there are many more questions you can ask about this person’s physicality or physical body.

As a result of dividing our subject into three distinct parts, we now have a clear picture of the main structure of this essay.

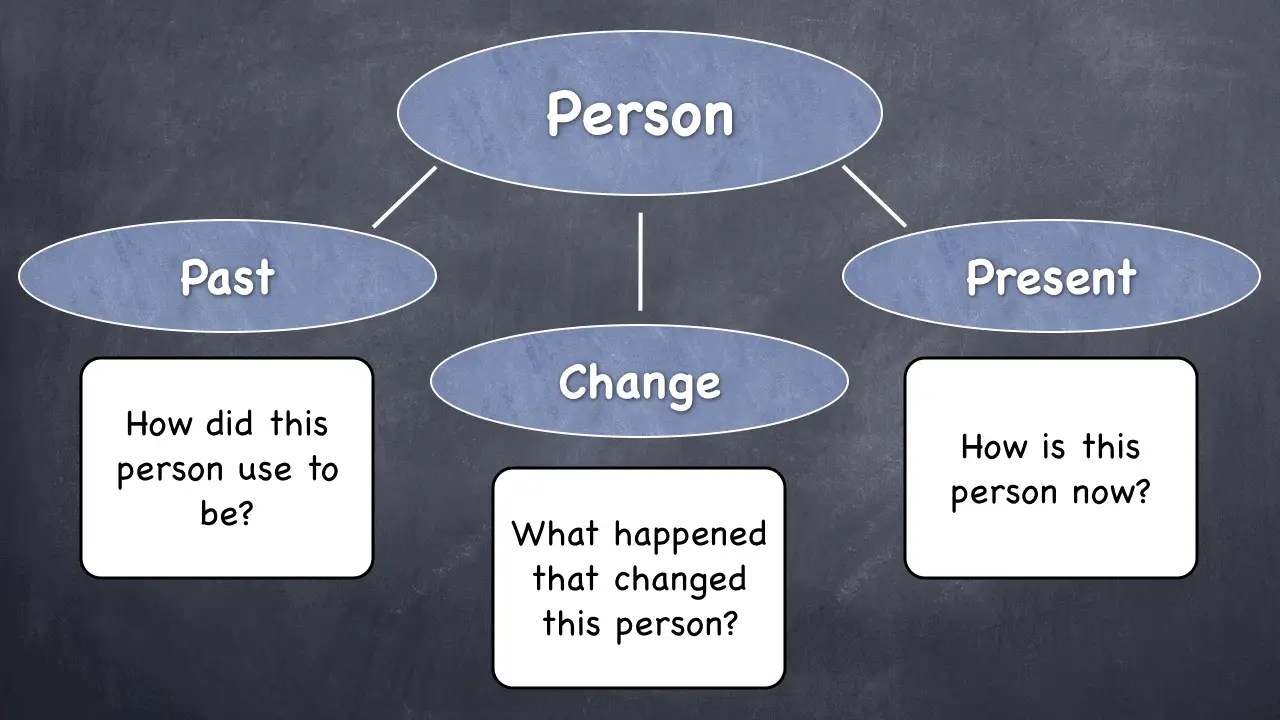

Another Way to Divide a Subject – Change

Another great way to talk about a person is to discuss a change, any kind of a change.

Change as an idea lends itself very well to the Power of Three because it involves three parts.

Think of a person who has lost weight, for example. What are the three parts of that change?

First, it’s how much the person weighed in the past, before the change. Second, it is the agent of change, such as an exercise program. And third, it is the result; it’s how much the person weighs after the change has happened.

This structure is applicable to any kind of a change.

In this part of the essay, you can discuss anything that is relevant to the way things were before the change took place. It’s the “before” picture.

Some of the questions to ask are:

“How did this person use to be in the past?”

“How did the old state of things affect her life?”

The Agent of Change

This can be anything that brought about the change. In the case of weight loss, this could be a diet or an exercise program. In the case of education, this could be college.

Some of the question to ask are the following:

“What happened? What are the events or factors that made this person change?”

“What actually brought about the change in this person?”

Maybe the person went to college, and college life changed this person.

Maybe this person went to prison. That can change a person’s life for the better or worse.

Maybe she underwent some interesting sort of a transformation, such as childbirth or a passing of a loved one. It could even be a car accident or some other serious health hazard.

The Present

This is the “after” picture. In this section, you would describe the state of this person after the change has taken place.

This part of the essay would answer the questions:

“How is this person now?”

“What has changed?”

Note that the resulting change doesn’t have to be set in the present day. This change could have happened to a historical figure, and both the “before” and “after” would be in the past.

And there you have it. You have three parts or three sections, based on some kind of a change.

This is a wonderful way to discuss any person, especially if you’re writing a biography of a public or historical figure.

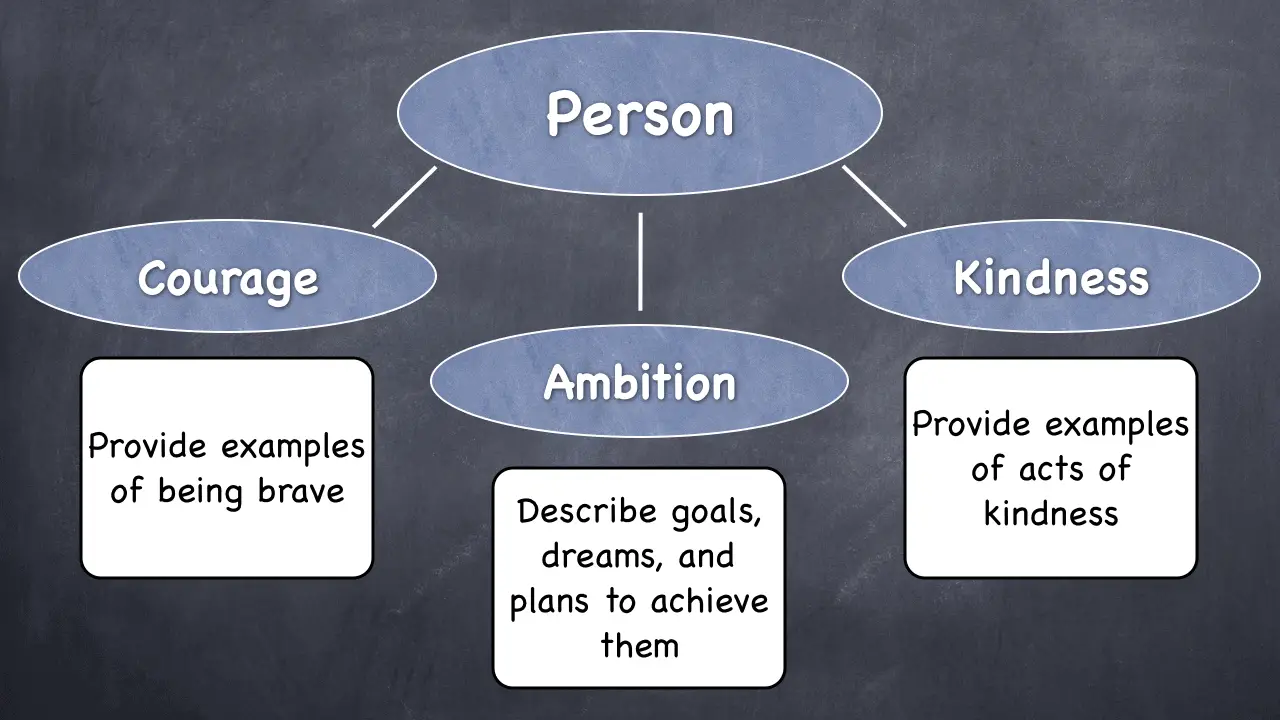

A Third Way to Divide a Subject – Personal Qualities

A great way to discuss a person, especially someone you know personally, is to talk about their qualities of character.

A person can have many character qualities. And in this case, the Power of Three helps you narrow them down to three of the most prominent ones.

Let’s pick three personal qualities of someone you might know personally.

In this section, you could simply provide examples of this person showing courage in times of trouble.

Here, you would talk about the goals and dreams this person has and how she plans to achieve them.

Here, just provide examples of acts of kindness performed by this person.

Three major qualities like these are enough to paint a pretty thorough picture of a person.

Discussing personal qualities is a great way to add content to your biographical essay. And it works in a discussion of any human being, from a friend to a distant historical figure.

How to Write a Longer Biography Essay

At this point, you have all the building blocks to write an excellent essay about a person.

By the way, if you struggle with essay writing in general, I wrote a detailed guide to essay writing for beginners .

In this section, I want to show you how to use what you’ve learned to construct one of those big papers, if that’s what you need to do.

If you have to write a basic essay of about 600-1000 words, then just use one of the simple structures above.

However, if you need to write 2,000 – 5,000 words, or even more, then you need a deeper structure.

To create a deeper, more complex structure of a biography essay while still keeping the process easy to follow, we’ll simply combine structures we have already learned.

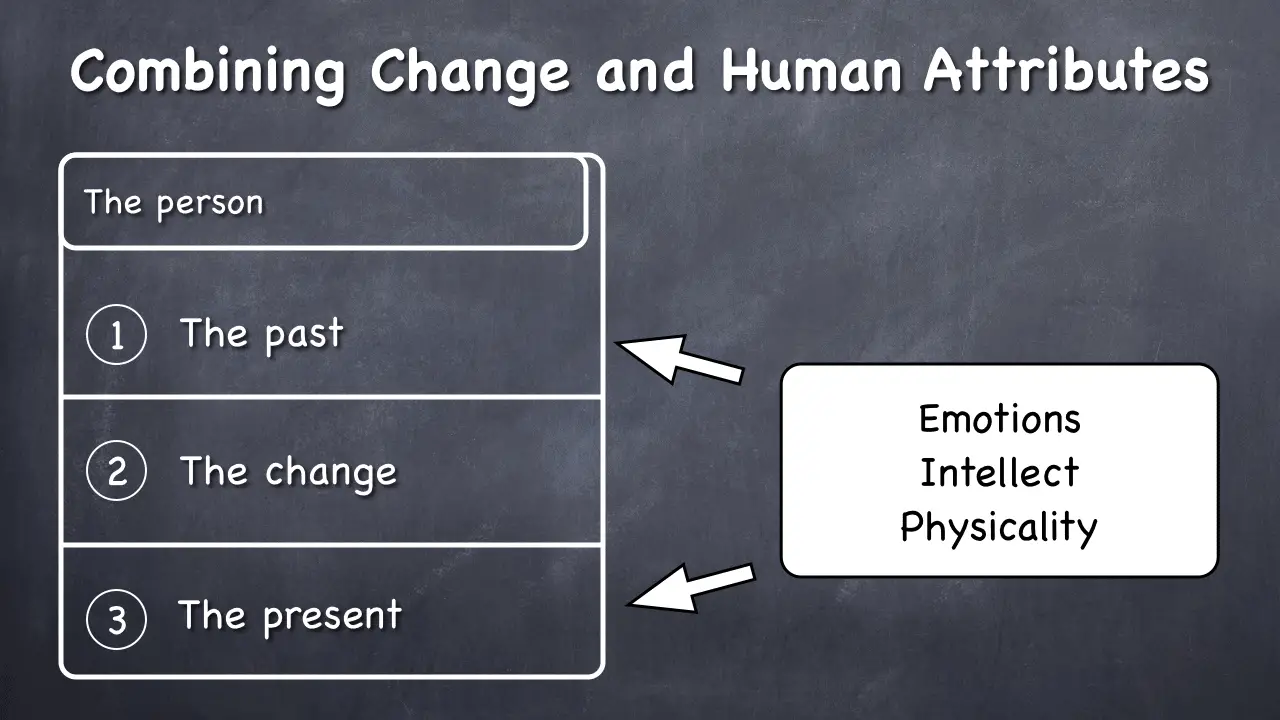

Combining Change and Human Attributes

Let’s say that you decided that your main point will be about this person’s change as a result of some event.

Then, you will have three main sections, just like I showed you in writing about any change.

In effect, you will be discussing:

- How this person was in the past (before the change)

- The actual change

- What happened as the result

You now have divided your essay into three parts. And now, you can use the Power of Three again to divide each main section into subsections.

Section 1. You can talk about how this person was in the past, in terms of:

- Physicality

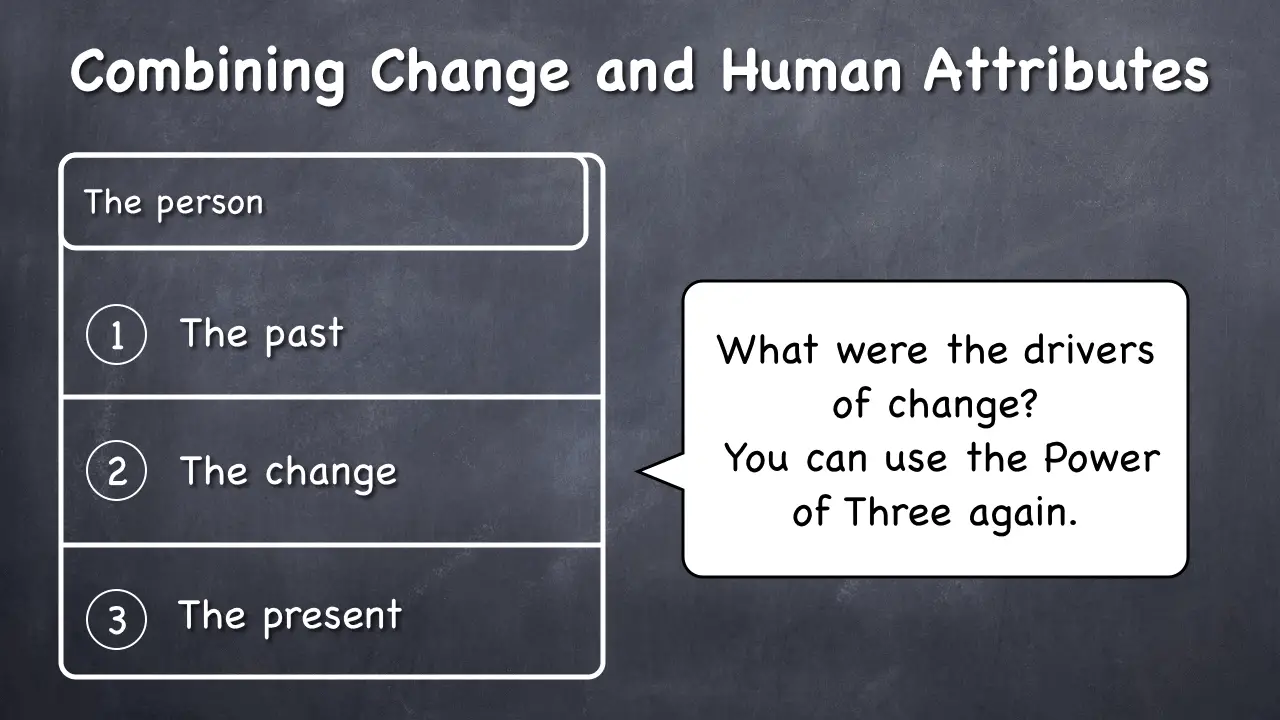

Section 2. When you talk about change, you can still use the Power of Three.

You can ask the question, “What were the drivers of change?”

You can be even more specific here and ask, “What were the three drivers of change?”

And then you answer that question.

For example, if this person went to college, some of the factors of change could have been:

- The pressure of having to submit work on time.

And those factors changed this person.

Section 3 . As a result of the change, how is this person now, in terms of:

Other Ways to “Divide and Conquer”

Note that there are many more aspects of any person that you can discuss.

Some of them include:

- Outer vs Inner life.

- Personal vs Professional life.

- Abilities or Skills.

You can pick any other aspects you can think of. And you can use the Power of Three in any of your sections or subsections to write as much or as little as you need.

Tips on Writing a Biographical Essay

You can apply any of these techniques to writing about yourself..

When you’re writing about yourself, that’s an autobiographical essay. It is simply a piece of writing in which you reveal something about your life.

You can take any of the ways we just used to divide a human being or her life into parts and apply them to yourself.

This can work in a personal statement or a college admissions essay very well.

Here’s a list of things to narrow your autobiographical essay topic:

- One significant event in your life

- A change that you decided to make

- A person you met who changed your life (or more than one person)

- The biggest lesson you’ve ever received in life

- Your goals and aspirations (talking about the future)

Structure your essay as if it is an argumentative essay.

Most of the research papers and essays you’ve written up to date have probably been expository. This means that you stated an argument and supported it using evidence.

A biographical essay is not necessarily expository. You don’t always have something to argue or prove. You could simply tell the reader a story about yourself or describe a period in your life.

But you can and probably should still use the structures presented in this tutorial because this will make it much easier for you to organize your thoughts.

Stay focused on your subject.

Once you know your structure, just stick to it. For example, if you’ve chosen to talk about a person’s courage, ambition, and kindness, these three qualities will carry your essay as far as you want.

But don’t sneak in another quality here and there, because that will dilute your argument. Be especially careful not to write anything that contradicts your view of this person.

If you use contradictory information, make sure it is a counterargument, which is a great technique to add content. You can learn how to use counterarguments in this video:

Hope this helps. Now go write that biography essay!

How to Write a 300 Word Essay – Simple Tutorial

How to expand an essay – 4 tips to increase the word count, 10 solid essay writing tips to help you improve quickly, essay writing for beginners: 6-step guide with examples, 6 simple ways to improve sentence structure in your essays.

Tutor Phil is an e-learning professional who helps adult learners finish their degrees by teaching them academic writing skills.

Recent Posts

How to Write an Essay about Why You Want to Become a Nurse

If you're eager to write an essay about why you want to become a nurse, then you've arrived at the right tutorial! An essay about why you want to enter the nursing profession can help to...

How to Write an Essay about Why You Deserve a Job

If you're preparing for a job application or interview, knowing how to express why you deserve a role is essential. This tutorial will guide you in crafting an effective essay to convey this...

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Memoir coach and author Marion Roach

Welcome to The Memoir Project, the portal to your writing life.

Writing Lessons: How to Write Someone Else’s Story

WRITING SOMEONE ELSE’S STORY

by Marvin Rapp

“Be yourself; everyone else is already taken.” (Oscar Wilde)

Writing honestly about oneself is rarely an easy exercise. Where should I begin my story? How much should I reveal? Who should I not offend? Who should I yes offend? How then do these challenges stack up when the story you are writing is not even your own?

Of course, I can only speak from my own experience, which for the record, was my first attempt at writing anybody’s story. When my wife, Lori, decided to write a cookbook of the recipes from our bakery and catering business of twenty-one years, I suggested we include the story behind all that delicious food. In short, we should write a foodoir, in today’s parlance.

Fair enough, but was I up to the task of being an objective raconteur? After all, I do appear somewhat incidentally in Lori’s story; nevertheless, it remained her story that I must tell, without subverting her voice. That seemingly innocent codicil is far more difficult to adhere to than it sounds. Every writer wants to leave his own imprint on whatever it is he may be putting to print, even if the subject happens to be one’s own wife. There is always that urge to be wittier or more savvy- sounding than your subject. In a nutshell, you must be prepared to put your own ego on the back burner.

Granted, my burden was somewhat eased by virtue of my spending the past twenty-three years waking, working, and breathing side by side with my partner. It is safe to say that Lori’s voice resides constantly inside my head.

I sensed I was on the right track with our project when every single volunteer who agreed to read my never-ending drafts remarked that they felt as if Lori was speaking to them personally. For me that is consolation enough, together with Lori agreeing to add my name (in smaller print, mind you) to the cover.

Secrets from Lori Rapp’s Kitchen, an excerpt

Chapter One

Tell me what you eat, I’ll tell you who you are.

— Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

I was born in 1959 in Toronto, the child of Holocaust survivors Helen and David Slutzki, who had married in 1958 and settled in Canada that same year. Yiddish was the lingua franca in our household, and that was the only language I spoke until kindergarten. Of course, at the time this seemed perfectly acceptable to my parents since their entire circle of friends consisted of greeners , or newcomers, like themselves who had miraculously survived the horrors of the Second World War, and had come to Canada with the hope of re-creating their broken lives. My parents seemed to be always labouring to earn a living; it was their single greatest preoccupation. They really led an unpretentious life. They rarely entertained or travelled, they hardly ever went out, they just worked hard to ensure that my brother, and I received the best private school education — and to put food on the table.

Not just any food, mind you. Whereas work was an unfortunate fact of life, for my folks food was their real obsession. Without any doubt, food was king in our house, secondary in importance only to health, and possibly education. Absolutely everything pertaining to food was an issue of some importance. Our family did not simply sit down to enjoy a meal together — that would have been far too easy. First came the whole ordeal of shopping — oddly enough the debate rarely concerned the price of anything. The focus of attention had more to do with the freshness or the size or the colour of what was about to be purchased. Whatever the food item happened to be, it was fussed over mercilessly before it was served, and then scrupulously analyzed after it was eaten. Every meal was either an occasion for praise or criticism, in most cases a combination of both. At the centre of this entire production loomed my father; a fastidious carpenter by trade, his seal of approval was the ultimate litmus test for any food prepared in our household.

From an early age, I remember awakening every morning, often while it was still dark outside, to the sounds of my parents scurrying about the kitchen, making breakfast, and packing lunch for my father ̶ the daily big thermos filled with steaming hot coffee accompanied by hefty sandwiches of thickly sliced rye bread. My family sat around the Formica kitchen table, filling up on freshly cooked oatmeal, cream of wheat, or scrambled eggs — my parents firmly believed that breakfast was the most important meal of the day, at least until lunch was served, and then later supper.

My mother and father were hardly gourmands, but our house was forever filled with the smells of hearty old-world cooking. And yet something as unassuming as a traditional mushroom barley soup could spark the most animated of exchanges — either the soup was thick as porridge or too watery and without enough seasoning, invariably never hot enough for my father’s liking. Even the timing of its serving was subject to heated debate as my father insisted it be served after the main course, when everyone else was too full to appreciate it, because he claimed it was good for the digestion.

A highly opinionated man under any circumstance, nothing aroused my father’s passion more than the subject of his stomach’s well-being. Had he had his way, every meal would have begun with a piece of herring and at least one shot of whisky — come to think of it, this was also supposed to be good for the digestion. And who could argue with his reasoning? My father remained as strong as a bull until the age of seventy-eight, indifferent to conventional medical wisdom. The man never ceased to amaze and confound me. A stickler for fresh food, he routinely planted cucumbers and tomatoes along the sides of our tiny bungalow. From May until the first frost, my brother Mark and I were expected to pick the daily haul before dinner to maximize its freshness. Everybody else’s parents planned their end-of-week shopping for Thursday to avoid any last-minute crises before the Sabbath — that would have been too conventional for my father. Two hours before candle lighting, signifying the beginning of the Sabbath, he would come home laden with fresh produce and other treats. In typical fashion, he would present my bewildered mother with an equally enormous cauliflower, broccoli, and cabbage, and then insist that she prepare all three cruciferous vegetables for that night’s supper. Ignoring her protests, he could be heard mumbling to himself all the way into the shower about how beautiful and crisp his choices were, and how gorgeous were the big white mushrooms that he picked. “Helen!!” he would bark between latherings. “Cook them up with lots of onions. Only ninety-nine cents a pound! Can you believe it? Only by the Italeiner !”

You might think that a man so fixated on freshness would avoid, like the plague, any and all commercially processed food products. Not so my dad. He had his cravings, most of which remained a mystery to the rest of the family. High on his list of indulgences were Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix, Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup, and Libby’s deep-browned baked beans (until somebody accidentally purchased a can with pieces of pork in it — a very big no-no in a kosher kitchen!). A special place in his heart was reserved for his beloved Mallomars, the consummate expression of culinary ingenuity. With childish glee, he would savour this exquisite combination of graham cracker, raspberry jam, marshmallow, and chocolate glaze, extolling its perfection to anybody within earshot.

Only years later when I began catering did I realize that my father’s food quirks were literally flowing through my veins. “You know,” he smiled one day, as if to confirm my new career choice, “my mother, your Yiddish namesake, was the caterer in Mir, my home town in Lithuania.” Go figure!

If my father was the general in our household kitchen, my mother was the dutiful staff sergeant. Day in and day out, she toiled in the trenches faithfully dishing out her version of comfort food. Faced with the unenviable task of pleasing everybody, she embraced her challenge with a resolute optimism that defied explanation. Unfortunately her mission was doomed from the outset; whereas my mother wanted nothing more than to nurture everyone, my father’s sense of compromise required that everybody simply agree with him. He couldn’t understand why the rest of us didn’t appreciate our grilled meat charred beyond any acceptable degree of well-done, or our baked goods left uncovered until their outer layer was dry as Melba toast.

Then again, what could we have expected? My father grew up in Lithuania where the radish was considered an exotic vegetable. My mother, on the other hand, had a slightly worldlier upbringing. Her hometown of Slatinskiye Doli, Czechoslovakia, was nestled in the foot of the Carpathian Mountains near the borders of Romania and Hungary, and as such was influenced by the richness of Hungarian cuisine. She often spoke nostalgically about the wonderful foods she enjoyed as a young girl: knockerlach (dumplings), sweet noodles tossed with poppy seeds , makosh (yeast cake), and — her personal favourite — mamaliga (polenta), in all its gooey, cheesy goodness. My mother would regale us with stories of her foraging in the surrounding woods for wild mushrooms, or picking thorny gooseberries in her backyard that her mother magically transformed into jams and compote. As a special treat, she and her siblings would suck on pieces of honeycomb, courtesy of her father’s beehives.

It seems now, in retrospect, that my childhood exposure to all these vivid tales and memories of old-world cooking was an essential step in my own culinary education. Even though it was the only world that I knew, I realized from an early age that it was just not going to do it for me. Bread served with pasta and potatoes — possibly a bit excessive, ya think? Yet, how was a sheltered, second-generation child supposed to satisfy her cravings for something, anything, a bit more trendy and glamorous than schmaltz herring? (Don’t get me wrong, today I would kill for some honest-to-goodness schmaltz herring.)

Enter my saviour, my friend Naomi. Her parents were also Czech Holocaust survivors, but to me they seemed to have emigrated from a different continent than my parents. Naomi’s father never, at least to my knowledge, lay on his living room couch in his sleeveless undershirt and garishly plaid Bermuda shorts like my father was fond of doing. I can still picture her dad relaxing in his den on a leather recliner absorbed in what for me was totally foreign — the strains of some beautiful classical composition. In their home I was introduced to the glorious tastes of French onion soup, mushroom quiche, and gazpacho. In their company I attended my first ballet and visited my first coffee shop. All of this paled in comparison to the sheer delight I experienced attending some of Naomi’s family’s elegant house parties. In utter amazement I would stare wide-eyed, transfixed by the sight of uniformed waitresses meticulously carving a smoked turkey or elegantly serving the family’s signature nut torte. I knew already back then that I longed to somehow be a part of this world. My timely exposure to high society, as it were, was all the inspiration I needed to try to jazz up my mother’s kitchen.

I could not have been more than fourteen when I concocted my first original dessert: individual frosted glass bowls filled with layers of graham cracker crust, Jell-O, drained fruit cocktail, and then Jell-O with the fruit folded with non-dairy whipped cream. It was no Cordon Bleu classic, but as far as my family was concerned, it could just as well have been one. What can I say? Ecstatic, enthusiastic, they were thrilled beyond my modest expectations. One brief encounter with “modernity” and our appetites were forever changed. That was all the encouragement I needed. I hit the pavement running and haven’t looked back since.

Babysitting became a valuable opportunity to study my employers’ cookbooks and magazines, and hopefully to spy out some coveted family recipe. Grade twelve was my breakout year. I organized my first party, a “poor man’s dinner” for a group of eight girlfriends, complete with carefully chosen take-home hostess gifts (I already had the knack for catering, I just didn’t realize it back then). To this day I can cite the entire menu and recall what dish each of us contributed. Even more vividly etched in my memory is the conviviality and coziness we all experienced sitting in my parents’ dining room, feeling all grown up. It was my own “Babette’s Feast.”

Marvin and I lived only a few blocks from each other, and we shared a lot of meals together during the two year-period of our dating and engagement. I was studying Jewish education at York University while Marvin split his time between working in an upscale bookshop and completing his master’s degree in English literature at the University of Toronto. Four nights a week he sat, supposedly writing, at his library cubicle until closing time at midnight, after which he made the twenty-minute drive to my house where a full-course supper awaited him. For the better part of a year, my mother and I fattened him up with a combination of her traditional European cooking and my latest culinary experiments. This almost nightly ritual of post-midnight rendezvous raised a few eyebrows from my parents’ elderly neighbours. “You should know, Mrs. Slutzki, that your daughter’s boyfriend is leaving your house after three in the morning. You know, Mrs. Slutzki, that doesn’t look so good.” Me, I always wondered what these people spying on us were busy doing themselves up at that hour.

I suppose it should never have come as such a surprise when years later Marvin and I got into the food trade; after all, we had spent an awful lot of time together indulging our appetites. By the time we got married in 1981, I was more than anxious to begin cooking in earnest. From my years of zealous prepping, I knew that a serious cook required a well-equipped kitchen. With my modest budget in tow, I acquired all the Calphalon and Le Creuset pots, Kosta Boda serving pieces, and Evesham cookware that I could possibly eke out. The next task at hand was to stock my pantry with as many new and exotic products that came to market. After all, it was the early eighties and food was the rage. Armed with my subscriptions to Gourmet and Bon Appétit magazines, I scoured the fancy food shops in Toronto’s Bayview Village, Yorkville, and Avenue Road to discover the latest arrivals. I hardly ever came home without something new like pine nuts, wild rice, or New Zealand kiwifruit.

I was totally in my element. My cookbook collection was expanding copiously in sync with our waistlines. Dozens of hours a week were spent puttering around my kitchen with my coveted Time Life series, baking and cooking up a storm. Luckily for me, I had a most eager and compliant guinea pig in my husband. Marvin’s undeveloped palate was in a league of its own. Although his maternal grandparents maintained a produce stall for almost forty years in the farmers’ market in Hamilton, he had no clue what a zucchini or an eggplant tasted like. His family regarded them as food fit for the lockshen — Yiddish for noodles, a euphemism for “Italians.” Kohlrabi and fennel, forget it. The man was like putty in my hands, only too willing to indulge me in my experiments.

And experiment was what I did, with a vengeance. Quantities knew no bounds; I was incapable of cooking just for the two of us. Weekdays, weekends, it made no difference. I loved entertaining my friends and was never intimidated by a new recipe. Occasionally, in my over-eagerness I’d overreach my skills and dive into uncharted waters. Homemade gnocchi, why not? Well, for openers, they weren’t quite al dente (in fact, they disintegrated when they hit the boiling water) and it took me two hours to clean up the kitchen for all my efforts. Then there was the mousseline-stuffed Dover sole (an unmitigated, expensive disaster) and a mushroom soufflé (never even stood a chance). But, more often than not, my developing repertoire of self-taught dishes elicited moans and groans of approval.

The first Tuesday of every month was the day reserved for fresh, farm-raised rainbow trout courtesy of our neighbourhood trendy food shoppe, The Nutcracker Sweet. It became something of a tradition to host dinner parties for our friends; in actuality, it was an excuse to indulge in a revelry of dishes laden with butter and cream. And chocolate. There could never be enough chocolate.

What about chicken, you ask? Most newlyweds content themselves with purchasing one whole chicken at a go. Pas moi . My friend Elaine’s brother ran a business delivering cases of no fewer than eighteen freshly slaughtered chickens to your doorstep. As long as we were buying enough chickens to feed a football team, we figured why not squeeze an upright freezer into our starter apartment. Of course, it would take the two of us nearly an entire evening to cut, trim, and wrap this haul, not to mention the obligatory preparation of schmaltz (fried chicken fat) with griebens (cracklings) and fried onions. I kid you not. Fortunately cholesterol hadn’t been discovered yet in 1981.

I was determined to discover the best of everything. Chocolate chip cookies, lemon curd, or muffins, I’d zero in on my target and then spend the better part of a month checking and testing recipes for each dish until I was satisfied. Needless to say, I gained twenty-eight pounds in my first year of marriage. Total strangers would kindly offer me a seat on the bus, and elderly women in our synagogue would knowingly smile and cluck at me, all assuming I was pregnant. What could I do? There were so many cheesecake recipes yet to be sampled…

My addiction to butter and cream had no ideological bent; I mean, I still salivated over a choice cut of rare beef. Simply put, the creative options open to dairy cooking were far too tempting for me to resist even at the expense of our traditional, religious celebrations. Amongst our peers, Sabbath eve dinner was considered the focal meal of the week. Any menu that deviated too drastically from the ubiquitous chicken soup, roast chicken, and kugel was considered taboo; offering cream of lettuce soup with fresh salmon and parmesan-baked potatoes was the culinary equivalent of serving sloppy joes at a Thanksgiving feast. But I knew better. As soon as our invited guests overcame the initial shock of what lay in store for them, they were easily converted. I cannot recall anybody refusing an invitation simply because brisket wasn’t on the menu.

A dedicated schoolteacher by day, I taught second grade Hebrew and Jewish studies at a number of Toronto’s private day and afternoon schools. (Although cooking wasn’t on the curriculum, one of my students, Rachel, went on to become an accomplished pastry chef who has wowed restaurant-goers in some of Manhattan’s most trendy eateries.) When not teaching, I spent much of my available spare time indulging my food fantasies. I wore out the bindings of my Moosewood and Silver Palate cookbooks in my quest for what was for me new, exciting and unconventional. Chicken Marbella. Need I say more? Capers, prunes, and green olives — that combination turned on its head any preconceived notion of what I had thought chicken could be. Say goodbye to onion soup mix and corn flake crumbs!

Yearning to improve my skills and broaden my horizons, I enrolled on a lark with my friend Elaine in a pastry course given by one of Canada’s top cooking instructors and food gurus, Bonnie Stern. She introduced me to the joys of Swiss chocolate, buttery tart crusts, and airy cream puffs. To this day I carry with me one of her trusted maxims: It’s better to indulge in one small square of exquisite chocolate or a delicious apple than to squander precious calories on an undeserving dessert. I loved every second spent in her classroom, never dreaming that the skills I acquired would serve me professionally years later.

Authors’ bio

Lori and Marvin Rapp emigrated from Toronto, Canada to Jerusalem, Israel in 1986. For twenty-one years they owned and operated La Cuisine, a popular bakery and catering establishment.

A teacher by profession, Lori honed her baking skills at the renowned L’Ecole Lenôtre in Paris. Today she divides her time between teaching baking and cooking workshops and working as a private chef.

Marvin is Lori’s partner in life and labour. He holds a masters degree in English literature from the University of Toronto, and when not busy sampling Lori’s cooking he enjoys dabbling in the written word.

Secrets from Lori Rapp’s Kitchen is their first book.

Want to work with Marion Roach Smith to write memoir? I now teach four online memoir writing classes , and work as a memoir coach . Come see me and let me teach you how to get started writing memoir, how to move your writing along, or how to finish what you’ve got.

Share this:

Related posts:

- Two Sides to the Same Story? At Least. What to Do? Write Your Version.

- Writing Lessons: How to Write A Personal Story & Make it Public, with Diane Cameron

- Two Sides to the Same Story? At Least. Here’s My Sister’s Version

GET THE QWERTY PODCAST

Subscribe free to the podcast

Reader interactions.

Joan Z. Rough says

September 23, 2014 at 8:00 pm

I just ate dinner, read this wonderful first chapter, and now I’m hungry and ready for another meal. Lovely piece. Thanks.

Marvin Rapp says

September 24, 2014 at 10:03 am

Thank you for your warm comments. Now you can appreciate what I experience every day.

Judith Henry says

September 24, 2014 at 9:24 am

Marvin and Lori, Mazel tov! After reading this excerpt, it’s clear your book is food for both body and soul. Wishing you much success. Judith

September 24, 2014 at 10:08 am

Dear Judith,

Thank you kindly.

Kay Dixon says

September 25, 2014 at 1:54 pm

I look forward to reading your book and perhaps testing some of your recipes, too. From the excerpt, I think I have been in your kitchen or maybe we just share the same cook book collection. But you definitely have more courage in the kitchen than I do. Best wishes for success with this venture.

September 28, 2014 at 4:15 am

Our book is available from Amazon. As far as sharing our cookbooks, you are welcome to visit our kitchen if you are ever in our neck of the woods.

Stephen W. Leslie says

September 25, 2014 at 3:33 pm

It never occured to me to consider writing a memoir for someone else. I found the whole idea a bit mind bending. I agree with the author that it must have been hard to accurately “be” someone else……but I also can see the other side, that in some ways he could be a more objective observer. The article made me feel curious to hear her reaction to his book.

September 28, 2014 at 4:27 am

Lori loves to talk, I prefer to write. It was a natural, collaborative effort.

September 26, 2014 at 12:48 pm

Cook for two? Impossible in my Italian kitchen. I love your solution….who doesn’t like to be fed? The voice of this piece speaks to me. Can’t wait to indulge in the entire memoir.

September 28, 2014 at 4:42 am

You definitely speak our language. It is usually a safe bet to heed the advice of Julia Child – Always start out with a larger pot than you think you need.”

Robert Patterson says

October 5, 2014 at 7:38 pm

I love the feeling you get when you read the story. You feel like you are at the kitchen table and just sharing stories about each others families. Its warm, inviting and very human with no pretense about what should be expected. I would never know that there was more then one voice in the story. Bob Patterson

October 7, 2014 at 8:51 am

That’s probably because Lori told me what to write. Actually, I am a firm believer in the old adage that “reality is stranger than fiction.” I discovered that if you stick to the “script,” the story pretty much speaks for itself.

SITEWIDE SEARCH

Join me on instagram, mroachsmith.

- Phone: (617) 993-4823

- August 1, 2020

Supplemental Specifics: How to Write about Someone Else

As you probably already know, the point of your college application is to give admissions committees a solid sense of who you are. You’ve written a highly personal college essay, and probably some supplementals on your intellectual and extracurricular activities and your leadership experience. Maybe on your intended major and career plans as well.

But many colleges also give you the opportunity to write about other people. This year, Princeton proposes the following prompt:

“Tell us about a person who has influenced you in a significant way.”

Many other colleges ask similar questions. Some ask you to talk specifically about your peers, your family, etc.

Should you talk about a role model, a peer, a family member?

As always, you want to be strategic about selecting prompts when you’re given a selection from which to choose. If you’re applying to Princeton, take a look at the three other prompts available (you’re asked to choose one). They concern: “great challenges facing our world”; the value of culture; and a favorite quote, which you’re asked to elaborate on and relate to a value you’ve learned.

Elaborating on a quote is pretty open-ended, and could be a good choice—but be very careful when it comes to the quote. You’re going to want to have something truly interesting at the ready. Avoid anything predictable: “To be or not to be,” for example, is not a promising opening to an essay that is supposed to show your uniqueness. The culture question is essentially a “community” essay. You may want to choose this prompt if you have a unique cultural background that will help differentiate you from other applicants. I would absolutely recommend against tackling any of the “great challenges facing our world.” I personally can’t understand how high school seniors are supposed to write about major issues like this in a meaningful, personal way. If you truly believe you have something important to say, resist the temptation of trying to solve huge problems like climate change, the wage gap, the patriarchy etc. (The prompt doesn’t ask you for a solution.) Just speak from and about your own experience.

The “influence” essay may be the best choice for you here and elsewhere: often, writing an essay on someone else provides the chance for you to show something about yourself that is not already apparent in your application.

How to write the essay

Tell a story. Do not rattle off a series of general statements. (This, in my experience, is the most common mistake students make in their essays.) Before you begin worrying about whom you should write your essay on (I’ll get to that), ask yourself: what story can I tell?

For Princeton, the “influence” essay is hefty: you’ve got a word-limit of 650. You should approach it the same way you approached your college essay. Length will depend on where you’re applying, but the “role model” essay should tell a very personal story.

This essay is not about you—it’s about your role model. But it needs to say something meaningful about who you are. Your essay should describe the person who influences you, but it should tell a story only you can tell.

Great “role model” essays discuss people who have influenced you, challenged you, aggravated you in meaningful ways. Avoid morals: “And so, my friend, Jimmy, taught me the virtue of honesty, and I am a better person thanks to his influence;” “In conclusion, although I struggled initially to accept Allison’s criticism, in the end I took it to heart and became a better person as a result.” Resist the temptation to explain how this is all ultimately about you and how great you are. Tell a story about someone who is, or did something truly meaningful to you, who has changed how you think and act. You can say a lot about who you are through your choice of subject.

Whom should you write about?

Telling a great story is more important than choosing “the right” person to write about. Certain questions will restrict your choice (will ask you to write about a peer, a family member, etc.).

No topic (or, in this case, person) is ever truly off-limits, but I would avoid choosing a family member if possible. The reason is that most high school students (and I speak from my own experience of being seventeen) have a hard time regarding their parents and siblings with any real objectivity. Family member essays are often either angry rants or over-the-top panegyrics.

Famous people are also generally a poor choice. If you’re writing about someone you’ve never met, the chances are slim that your essay will turn out to be very personal, especially since folks like Oprah Winfrey, Pope Francis, and Lebron James are already role models for millions of people. On the other hand, if Ariana Grande was your babysitter (improbable scenario, I know), you may have a hard time talking about it without sounding like you’re simply bragging about the connection.

If you’re going to talk about a peer, I’d avoid relating an anecdote about a teammate during a sports game. The fact is that everyone who plays sports (and a lot of people do in high school) has meaningful connections with others on the field. The sports essay almost never comes across as particularly original or individual.

So who’s left? Peers off the sports field, for sure. Your rabbi, your cello teacher, that adult in your life who’s something of a parental figure, your boss at the gas station, the list goes on. Your choice should depend on the kind of story you think you can tell.

#collegeessays #collegeapplication #collegeadmission If you need any help with your essays, our team of college admissions consultants is ready to provide you with the guidance you need.

- College Applications , Supplemental Essays , The College Essay

What It’s Like to Be a First-Generation Student

How Your Extracurricular Activities Can Boost Your College Application

The Best Internship Opportunities for High School Students

- Partnerships

- Our Insights

- Our Approach

Our Services

- High School Roadmaps

- College Applications

- Graduate School Admissions

- H&C Incubator

- [email protected]

Terms and Conditions . Privacy policy

©2024 H&C Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, getting college essay help: important do's and don’ts.

College Essays

If you grow up to be a professional writer, everything you write will first go through an editor before being published. This is because the process of writing is really a process of re-writing —of rethinking and reexamining your work, usually with the help of someone else. So what does this mean for your student writing? And in particular, what does it mean for very important, but nonprofessional writing like your college essay? Should you ask your parents to look at your essay? Pay for an essay service?

If you are wondering what kind of help you can, and should, get with your personal statement, you've come to the right place! In this article, I'll talk about what kind of writing help is useful, ethical, and even expected for your college admission essay . I'll also point out who would make a good editor, what the differences between editing and proofreading are, what to expect from a good editor, and how to spot and stay away from a bad one.

Table of Contents

What Kind of Help for Your Essay Can You Get?

What's Good Editing?

What should an editor do for you, what kind of editing should you avoid, proofreading, what's good proofreading, what kind of proofreading should you avoid.

What Do Colleges Think Of You Getting Help With Your Essay?

Who Can/Should Help You?

Advice for editors.

Should You Pay Money For Essay Editing?

The Bottom Line

What's next, what kind of help with your essay can you get.

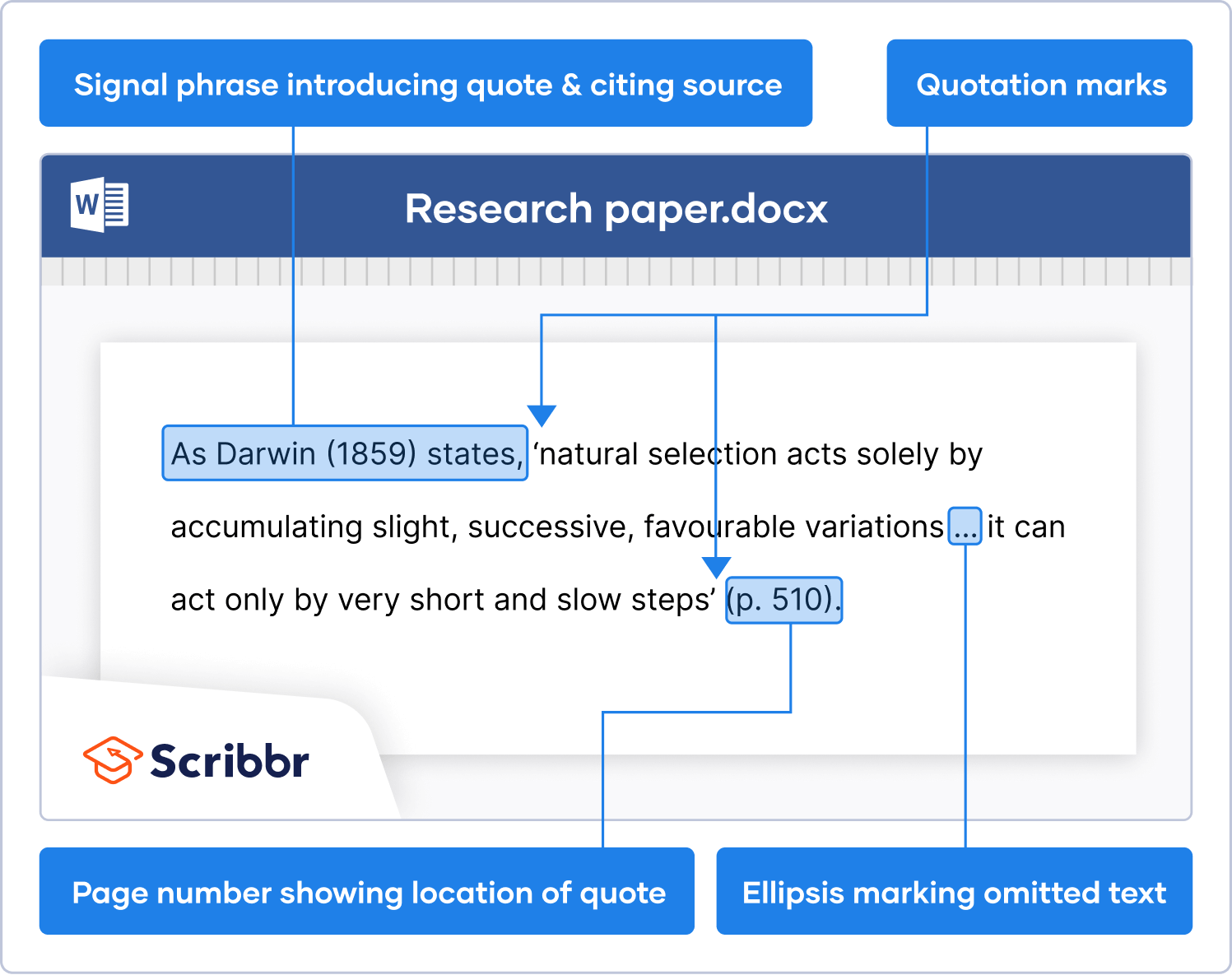

Rather than talking in general terms about "help," let's first clarify the two different ways that someone else can improve your writing . There is editing, which is the more intensive kind of assistance that you can use throughout the whole process. And then there's proofreading, which is the last step of really polishing your final product.

Let me go into some more detail about editing and proofreading, and then explain how good editors and proofreaders can help you."

Editing is helping the author (in this case, you) go from a rough draft to a finished work . Editing is the process of asking questions about what you're saying, how you're saying it, and how you're organizing your ideas. But not all editing is good editing . In fact, it's very easy for an editor to cross the line from supportive to overbearing and over-involved.

Ability to clarify assignments. A good editor is usually a good writer, and certainly has to be a good reader. For example, in this case, a good editor should make sure you understand the actual essay prompt you're supposed to be answering.

Open-endedness. Good editing is all about asking questions about your ideas and work, but without providing answers. It's about letting you stick to your story and message, and doesn't alter your point of view.

Think of an editor as a great travel guide. It can show you the many different places your trip could take you. It should explain any parts of the trip that could derail your trip or confuse the traveler. But it never dictates your path, never forces you to go somewhere you don't want to go, and never ignores your interests so that the trip no longer seems like it's your own. So what should good editors do?

Help Brainstorm Topics

Sometimes it's easier to bounce thoughts off of someone else. This doesn't mean that your editor gets to come up with ideas, but they can certainly respond to the various topic options you've come up with. This way, you're less likely to write about the most boring of your ideas, or to write about something that isn't actually important to you.

If you're wondering how to come up with options for your editor to consider, check out our guide to brainstorming topics for your college essay .

Help Revise Your Drafts

Here, your editor can't upset the delicate balance of not intervening too much or too little. It's tricky, but a great way to think about it is to remember: editing is about asking questions, not giving answers .

Revision questions should point out:

- Places where more detail or more description would help the reader connect with your essay

- Places where structure and logic don't flow, losing the reader's attention

- Places where there aren't transitions between paragraphs, confusing the reader

- Moments where your narrative or the arguments you're making are unclear

But pointing to potential problems is not the same as actually rewriting—editors let authors fix the problems themselves.

Bad editing is usually very heavy-handed editing. Instead of helping you find your best voice and ideas, a bad editor changes your writing into their own vision.

You may be dealing with a bad editor if they:

- Add material (examples, descriptions) that doesn't come from you

- Use a thesaurus to make your college essay sound "more mature"

- Add meaning or insight to the essay that doesn't come from you

- Tell you what to say and how to say it

- Write sentences, phrases, and paragraphs for you

- Change your voice in the essay so it no longer sounds like it was written by a teenager

Colleges can tell the difference between a 17-year-old's writing and a 50-year-old's writing. Not only that, they have access to your SAT or ACT Writing section, so they can compare your essay to something else you wrote. Writing that's a little more polished is great and expected. But a totally different voice and style will raise questions.

Where's the Line Between Helpful Editing and Unethical Over-Editing?

Sometimes it's hard to tell whether your college essay editor is doing the right thing. Here are some guidelines for staying on the ethical side of the line.

- An editor should say that the opening paragraph is kind of boring, and explain what exactly is making it drag. But it's overstepping for an editor to tell you exactly how to change it.

- An editor should point out where your prose is unclear or vague. But it's completely inappropriate for the editor to rewrite that section of your essay.

- An editor should let you know that a section is light on detail or description. But giving you similes and metaphors to beef up that description is a no-go.

Proofreading (also called copy-editing) is checking for errors in the last draft of a written work. It happens at the end of the process and is meant as the final polishing touch. Proofreading is meticulous and detail-oriented, focusing on small corrections. It sands off all the surface rough spots that could alienate the reader.

Because proofreading is usually concerned with making fixes on the word or sentence level, this is the only process where someone else can actually add to or take away things from your essay . This is because what they are adding or taking away tends to be one or two misplaced letters.

Laser focus. Proofreading is all about the tiny details, so the ability to really concentrate on finding small slip-ups is a must.

Excellent grammar and spelling skills. Proofreaders need to dot every "i" and cross every "t." Good proofreaders should correct spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and grammar. They should put foreign words in italics and surround quotations with quotation marks. They should check that you used the correct college's name, and that you adhered to any formatting requirements (name and date at the top of the page, uniform font and size, uniform spacing).

Limited interference. A proofreader needs to make sure that you followed any word limits. But if cuts need to be made to shorten the essay, that's your job and not the proofreader's.

A bad proofreader either tries to turn into an editor, or just lacks the skills and knowledge necessary to do the job.

Some signs that you're working with a bad proofreader are:

- If they suggest making major changes to the final draft of your essay. Proofreading happens when editing is already finished.

- If they aren't particularly good at spelling, or don't know grammar, or aren't detail-oriented enough to find someone else's small mistakes.

- If they start swapping out your words for fancier-sounding synonyms, or changing the voice and sound of your essay in other ways. A proofreader is there to check for errors, not to take the 17-year-old out of your writing.

What Do Colleges Think of Your Getting Help With Your Essay?

Admissions officers agree: light editing and proofreading are good—even required ! But they also want to make sure you're the one doing the work on your essay. They want essays with stories, voice, and themes that come from you. They want to see work that reflects your actual writing ability, and that focuses on what you find important.

On the Importance of Editing

Get feedback. Have a fresh pair of eyes give you some feedback. Don't allow someone else to rewrite your essay, but do take advantage of others' edits and opinions when they seem helpful. ( Bates College )

Read your essay aloud to someone. Reading the essay out loud offers a chance to hear how your essay sounds outside your head. This exercise reveals flaws in the essay's flow, highlights grammatical errors and helps you ensure that you are communicating the exact message you intended. ( Dickinson College )

On the Value of Proofreading

Share your essays with at least one or two people who know you well—such as a parent, teacher, counselor, or friend—and ask for feedback. Remember that you ultimately have control over your essays, and your essays should retain your own voice, but others may be able to catch mistakes that you missed and help suggest areas to cut if you are over the word limit. ( Yale University )

Proofread and then ask someone else to proofread for you. Although we want substance, we also want to be able to see that you can write a paper for our professors and avoid careless mistakes that would drive them crazy. ( Oberlin College )

On Watching Out for Too Much Outside Influence

Limit the number of people who review your essay. Too much input usually means your voice is lost in the writing style. ( Carleton College )

Ask for input (but not too much). Your parents, friends, guidance counselors, coaches, and teachers are great people to bounce ideas off of for your essay. They know how unique and spectacular you are, and they can help you decide how to articulate it. Keep in mind, however, that a 45-year-old lawyer writes quite differently from an 18-year-old student, so if your dad ends up writing the bulk of your essay, we're probably going to notice. ( Vanderbilt University )

Now let's talk about some potential people to approach for your college essay editing and proofreading needs. It's best to start close to home and slowly expand outward. Not only are your family and friends more invested in your success than strangers, but they also have a better handle on your interests and personality. This knowledge is key for judging whether your essay is expressing your true self.

Parents or Close Relatives

Your family may be full of potentially excellent editors! Parents are deeply committed to your well-being, and family members know you and your life well enough to offer details or incidents that can be included in your essay. On the other hand, the rewriting process necessarily involves criticism, which is sometimes hard to hear from someone very close to you.

A parent or close family member is a great choice for an editor if you can answer "yes" to the following questions. Is your parent or close relative a good writer or reader? Do you have a relationship where editing your essay won't create conflict? Are you able to constructively listen to criticism and suggestion from the parent?

One suggestion for defusing face-to-face discussions is to try working on the essay over email. Send your parent a draft, have them write you back some comments, and then you can pick which of their suggestions you want to use and which to discard.

Teachers or Tutors

A humanities teacher that you have a good relationship with is a great choice. I am purposefully saying humanities, and not just English, because teachers of Philosophy, History, Anthropology, and any other classes where you do a lot of writing, are all used to reviewing student work.

Moreover, any teacher or tutor that has been working with you for some time, knows you very well and can vet the essay to make sure it "sounds like you."

If your teacher or tutor has some experience with what college essays are supposed to be like, ask them to be your editor. If not, then ask whether they have time to proofread your final draft.

Guidance or College Counselor at Your School

The best thing about asking your counselor to edit your work is that this is their job. This means that they have a very good sense of what colleges are looking for in an application essay.

At the same time, school counselors tend to have relationships with admissions officers in many colleges, which again gives them insight into what works and which college is focused on what aspect of the application.

Unfortunately, in many schools the guidance counselor tends to be way overextended. If your ratio is 300 students to 1 college counselor, you're unlikely to get that person's undivided attention and focus. It is still useful to ask them for general advice about your potential topics, but don't expect them to be able to stay with your essay from first draft to final version.

Friends, Siblings, or Classmates

Although they most likely don't have much experience with what colleges are hoping to see, your peers are excellent sources for checking that your essay is you .

Friends and siblings are perfect for the read-aloud edit. Read your essay to them so they can listen for words and phrases that are stilted, pompous, or phrases that just don't sound like you.

You can even trade essays and give helpful advice on each other's work.

If your editor hasn't worked with college admissions essays very much, no worries! Any astute and attentive reader can still greatly help with your process. But, as in all things, beginners do better with some preparation.

First, your editor should read our advice about how to write a college essay introduction , how to spot and fix a bad college essay , and get a sense of what other students have written by going through some admissions essays that worked .

Then, as they read your essay, they can work through the following series of questions that will help them to guide you.

Introduction Questions

- Is the first sentence a killer opening line? Why or why not?

- Does the introduction hook the reader? Does it have a colorful, detailed, and interesting narrative? Or does it propose a compelling or surprising idea?

- Can you feel the author's voice in the introduction, or is the tone dry, dull, or overly formal? Show the places where the voice comes through.

Essay Body Questions

- Does the essay have a through-line? Is it built around a central argument, thought, idea, or focus? Can you put this idea into your own words?

- How is the essay organized? By logical progression? Chronologically? Do you feel order when you read it, or are there moments where you are confused or lose the thread of the essay?

- Does the essay have both narratives about the author's life and explanations and insight into what these stories reveal about the author's character, personality, goals, or dreams? If not, which is missing?

- Does the essay flow? Are there smooth transitions/clever links between paragraphs? Between the narrative and moments of insight?

Reader Response Questions

- Does the writer's personality come through? Do we know what the speaker cares about? Do we get a sense of "who he or she is"?

- Where did you feel most connected to the essay? Which parts of the essay gave you a "you are there" sensation by invoking your senses? What moments could you picture in your head well?

- Where are the details and examples vague and not specific enough?

- Did you get an "a-ha!" feeling anywhere in the essay? Is there a moment of insight that connected all the dots for you? Is there a good reveal or "twist" anywhere in the essay?

- What are the strengths of this essay? What needs the most improvement?

Should You Pay Money for Essay Editing?

One alternative to asking someone you know to help you with your college essay is the paid editor route. There are two different ways to pay for essay help: a private essay coach or a less personal editing service , like the many proliferating on the internet.

My advice is to think of these options as a last resort rather than your go-to first choice. I'll first go through the reasons why. Then, if you do decide to go with a paid editor, I'll help you decide between a coach and a service.

When to Consider a Paid Editor

In general, I think hiring someone to work on your essay makes a lot of sense if none of the people I discussed above are a possibility for you.

If you can't ask your parents. For example, if your parents aren't good writers, or if English isn't their first language. Or if you think getting your parents to help is going create unnecessary extra conflict in your relationship with them (applying to college is stressful as it is!)

If you can't ask your teacher or tutor. Maybe you don't have a trusted teacher or tutor that has time to look over your essay with focus. Or, for instance, your favorite humanities teacher has very limited experience with college essays and so won't know what admissions officers want to see.

If you can't ask your guidance counselor. This could be because your guidance counselor is way overwhelmed with other students.

If you can't share your essay with those who know you. It might be that your essay is on a very personal topic that you're unwilling to share with parents, teachers, or peers. Just make sure it doesn't fall into one of the bad-idea topics in our article on bad college essays .

If the cost isn't a consideration. Many of these services are quite expensive, and private coaches even more so. If you have finite resources, I'd say that hiring an SAT or ACT tutor (whether it's PrepScholar or someone else) is better way to spend your money . This is because there's no guarantee that a slightly better essay will sufficiently elevate the rest of your application, but a significantly higher SAT score will definitely raise your applicant profile much more.

Should You Hire an Essay Coach?

On the plus side, essay coaches have read dozens or even hundreds of college essays, so they have experience with the format. Also, because you'll be working closely with a specific person, it's more personal than sending your essay to a service, which will know even less about you.

But, on the minus side, you'll still be bouncing ideas off of someone who doesn't know that much about you . In general, if you can adequately get the help from someone you know, there is no advantage to paying someone to help you.

If you do decide to hire a coach, ask your school counselor, or older students that have used the service for recommendations. If you can't afford the coach's fees, ask whether they can work on a sliding scale —many do. And finally, beware those who guarantee admission to your school of choice—essay coaches don't have any special magic that can back up those promises.

Should You Send Your Essay to a Service?

On the plus side, essay editing services provide a similar product to essay coaches, and they cost significantly less . If you have some assurance that you'll be working with a good editor, the lack of face-to-face interaction won't prevent great results.

On the minus side, however, it can be difficult to gauge the quality of the service before working with them . If they are churning through many application essays without getting to know the students they are helping, you could end up with an over-edited essay that sounds just like everyone else's. In the worst case scenario, an unscrupulous service could send you back a plagiarized essay.

Getting recommendations from friends or a school counselor for reputable services is key to avoiding heavy-handed editing that writes essays for you or does too much to change your essay. Including a badly-edited essay like this in your application could cause problems if there are inconsistencies. For example, in interviews it might be clear you didn't write the essay, or the skill of the essay might not be reflected in your schoolwork and test scores.

Should You Buy an Essay Written by Someone Else?

Let me elaborate. There are super sketchy places on the internet where you can simply buy a pre-written essay. Don't do this!

For one thing, you'll be lying on an official, signed document. All college applications make you sign a statement saying something like this:

I certify that all information submitted in the admission process—including the application, the personal essay, any supplements, and any other supporting materials—is my own work, factually true, and honestly presented... I understand that I may be subject to a range of possible disciplinary actions, including admission revocation, expulsion, or revocation of course credit, grades, and degree, should the information I have certified be false. (From the Common Application )

For another thing, if your academic record doesn't match the essay's quality, the admissions officer will start thinking your whole application is riddled with lies.

Admission officers have full access to your writing portion of the SAT or ACT so that they can compare work that was done in proctored conditions with that done at home. They can tell if these were written by different people. Not only that, but there are now a number of search engines that faculty and admission officers can use to see if an essay contains strings of words that have appeared in other essays—you have no guarantee that the essay you bought wasn't also bought by 50 other students.

- You should get college essay help with both editing and proofreading

- A good editor will ask questions about your idea, logic, and structure, and will point out places where clarity is needed

- A good editor will absolutely not answer these questions, give you their own ideas, or write the essay or parts of the essay for you

- A good proofreader will find typos and check your formatting

- All of them agree that getting light editing and proofreading is necessary

- Parents, teachers, guidance or college counselor, and peers or siblings

- If you can't ask any of those, you can pay for college essay help, but watch out for services or coaches who over-edit you work

- Don't buy a pre-written essay! Colleges can tell, and it'll make your whole application sound false.

Ready to start working on your essay? Check out our explanation of the point of the personal essay and the role it plays on your applications and then explore our step-by-step guide to writing a great college essay .

Using the Common Application for your college applications? We have an excellent guide to the Common App essay prompts and useful advice on how to pick the Common App prompt that's right for you . Wondering how other people tackled these prompts? Then work through our roundup of over 130 real college essay examples published by colleges .

Stressed about whether to take the SAT again before submitting your application? Let us help you decide how many times to take this test . If you choose to go for it, we have the ultimate guide to studying for the SAT to give you the ins and outs of the best ways to study.

Anna scored in the 99th percentile on her SATs in high school, and went on to major in English at Princeton and to get her doctorate in English Literature at Columbia. She is passionate about improving student access to higher education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section: