What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples, Importance, & How to Improve)

Successful nursing requires learning several skills used to communicate with patients, families, and healthcare teams. One of the most essential skills nurses must develop is the ability to demonstrate critical thinking. If you are a nurse, perhaps you have asked if there is a way to know how to improve critical thinking in nursing? As you read this article, you will learn what critical thinking in nursing is and why it is important. You will also find 18 simple tips to improve critical thinking in nursing and sample scenarios about how to apply critical thinking in your nursing career.

What Is Critical Thinking In Nursing?

4 reasons why critical thinking is so important in nursing, 1. critical thinking skills will help you anticipate and understand changes in your patient’s condition., 2. with strong critical thinking skills, you can make decisions about patient care that is most favorable for the patient and intended outcomes., 3. strong critical thinking skills in nursing can contribute to innovative improvements and professional development., 4. critical thinking skills in nursing contribute to rational decision-making, which improves patient outcomes., what are the 8 important attributes of excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. the ability to interpret information:, 2. independent thought:, 3. impartiality:, 4. intuition:, 5. problem solving:, 6. flexibility:, 7. perseverance:, 8. integrity:, examples of poor critical thinking vs excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. scenario: patient/caregiver interactions, poor critical thinking:, excellent critical thinking:, 2. scenario: improving patient care quality, 3. scenario: interdisciplinary collaboration, 4. scenario: precepting nursing students and other nurses, how to improve critical thinking in nursing, 1. demonstrate open-mindedness., 2. practice self-awareness., 3. avoid judgment., 4. eliminate personal biases., 5. do not be afraid to ask questions., 6. find an experienced mentor., 7. join professional nursing organizations., 8. establish a routine of self-reflection., 9. utilize the chain of command., 10. determine the significance of data and decide if it is sufficient for decision-making., 11. volunteer for leadership positions or opportunities., 12. use previous facts and experiences to help develop stronger critical thinking skills in nursing., 13. establish priorities., 14. trust your knowledge and be confident in your abilities., 15. be curious about everything., 16. practice fair-mindedness., 17. learn the value of intellectual humility., 18. never stop learning., 4 consequences of poor critical thinking in nursing, 1. the most significant risk associated with poor critical thinking in nursing is inadequate patient care., 2. failure to recognize changes in patient status:, 3. lack of effective critical thinking in nursing can impact the cost of healthcare., 4. lack of critical thinking skills in nursing can cause a breakdown in communication within the interdisciplinary team., useful resources to improve critical thinking in nursing, youtube videos, my final thoughts, frequently asked questions answered by our expert, 1. will lack of critical thinking impact my nursing career, 2. usually, how long does it take for a nurse to improve their critical thinking skills, 3. do all types of nurses require excellent critical thinking skills, 4. how can i assess my critical thinking skills in nursing.

• Ask relevant questions • Justify opinions • Address and evaluate multiple points of view • Explain assumptions and reasons related to your choice of patient care options

5. Can I Be a Nurse If I Cannot Think Critically?

The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing

- How Nurses Use Critical Thinking

- How to Improve Critical Thinking

- Common Mistakes

Some experts describe a person’s ability to question belief systems, test previously held assumptions, and recognize ambiguity as evidence of critical thinking. Others identify specific skills that demonstrate critical thinking, such as the ability to identify problems and biases, infer and draw conclusions, and determine the relevance of information to a situation.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN, has been a critical care nurse for 10 years in neurological trauma nursing and cardiovascular and surgical intensive care. He defines critical thinking as “necessary for problem-solving and decision-making by healthcare providers. It is a process where people use a logical process to gather information and take purposeful action based on their evaluation.”

“This cognitive process is vital for excellent patient outcomes because it requires that nurses make clinical decisions utilizing a variety of different lenses, such as fairness, ethics, and evidence-based practice,” he says.

How Do Nurses Use Critical Thinking?

Successful nurses think beyond their assigned tasks to deliver excellent care for their patients. For example, a nurse might be tasked with changing a wound dressing, delivering medications, and monitoring vital signs during a shift. However, it requires critical thinking skills to understand how a difference in the wound may affect blood pressure and temperature and when those changes may require immediate medical intervention.

Nurses care for many patients during their shifts. Strong critical thinking skills are crucial when juggling various tasks so patient safety and care are not compromised.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN, is a nurse educator with a clinical background in surgical-trauma adult critical care, where critical thinking and action were essential to the safety of her patients. She talks about examples of critical thinking in a healthcare environment, saying:

“Nurses must also critically think to determine which patient to see first, which medications to pass first, and the order in which to organize their day caring for patients. Patient conditions and environments are continually in flux, therefore nurses must constantly be evaluating and re-evaluating information they gather (assess) to keep their patients safe.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created hospital care situations where critical thinking was essential. It was expected of the nurses on the general floor and in intensive care units. Crystal Slaughter is an advanced practice nurse in the intensive care unit (ICU) and a nurse educator. She observed critical thinking throughout the pandemic as she watched intensive care nurses test the boundaries of previously held beliefs and master providing excellent care while preserving resources.

“Nurses are at the patient’s bedside and are often the first ones to detect issues. Then, the nurse needs to gather the appropriate subjective and objective data from the patient in order to frame a concise problem statement or question for the physician or advanced practice provider,” she explains.

Top 5 Ways Nurses Can Improve Critical Thinking Skills

We asked our experts for the top five strategies nurses can use to purposefully improve their critical thinking skills.

Case-Based Approach

Slaughter is a fan of the case-based approach to learning critical thinking skills.

In much the same way a detective would approach a mystery, she mentors her students to ask questions about the situation that help determine the information they have and the information they need. “What is going on? What information am I missing? Can I get that information? What does that information mean for the patient? How quickly do I need to act?”

Consider forming a group and working with a mentor who can guide you through case studies. This provides you with a learner-centered environment in which you can analyze data to reach conclusions and develop communication, analytical, and collaborative skills with your colleagues.

Practice Self-Reflection

Rhoads is an advocate for self-reflection. “Nurses should reflect upon what went well or did not go well in their workday and identify areas of improvement or situations in which they should have reached out for help.” Self-reflection is a form of personal analysis to observe and evaluate situations and how you responded.

This gives you the opportunity to discover mistakes you may have made and to establish new behavior patterns that may help you make better decisions. You likely already do this. For example, after a disagreement or contentious meeting, you may go over the conversation in your head and think about ways you could have responded.

It’s important to go through the decisions you made during your day and determine if you should have gotten more information before acting or if you could have asked better questions.

During self-reflection, you may try thinking about the problem in reverse. This may not give you an immediate answer, but can help you see the situation with fresh eyes and a new perspective. How would the outcome of the day be different if you planned the dressing change in reverse with the assumption you would find a wound infection? How does this information change your plan for the next dressing change?

Develop a Questioning Mind

McGowan has learned that “critical thinking is a self-driven process. It isn’t something that can simply be taught. Rather, it is something that you practice and cultivate with experience. To develop critical thinking skills, you have to be curious and inquisitive.”

To gain critical thinking skills, you must undergo a purposeful process of learning strategies and using them consistently so they become a habit. One of those strategies is developing a questioning mind. Meaningful questions lead to useful answers and are at the core of critical thinking .

However, learning to ask insightful questions is a skill you must develop. Faced with staff and nursing shortages , declining patient conditions, and a rising number of tasks to be completed, it may be difficult to do more than finish the task in front of you. Yet, questions drive active learning and train your brain to see the world differently and take nothing for granted.

It is easier to practice questioning in a non-stressful, quiet environment until it becomes a habit. Then, in the moment when your patient’s care depends on your ability to ask the right questions, you can be ready to rise to the occasion.

Practice Self-Awareness in the Moment

Critical thinking in nursing requires self-awareness and being present in the moment. During a hectic shift, it is easy to lose focus as you struggle to finish every task needed for your patients. Passing medication, changing dressings, and hanging intravenous lines all while trying to assess your patient’s mental and emotional status can affect your focus and how you manage stress as a nurse .

Staying present helps you to be proactive in your thinking and anticipate what might happen, such as bringing extra lubricant for a catheterization or extra gloves for a dressing change.

By staying present, you are also better able to practice active listening. This raises your assessment skills and gives you more information as a basis for your interventions and decisions.

Use a Process

As you are developing critical thinking skills, it can be helpful to use a process. For example:

- Ask questions.

- Gather information.

- Implement a strategy.

- Evaluate the results.

- Consider another point of view.

These are the fundamental steps of the nursing process (assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate). The last step will help you overcome one of the common problems of critical thinking in nursing — personal bias.

Common Critical Thinking Pitfalls in Nursing

Your brain uses a set of processes to make inferences about what’s happening around you. In some cases, your unreliable biases can lead you down the wrong path. McGowan places personal biases at the top of his list of common pitfalls to critical thinking in nursing.

“We all form biases based on our own experiences. However, nurses have to learn to separate their own biases from each patient encounter to avoid making false assumptions that may interfere with their care,” he says. Successful critical thinkers accept they have personal biases and learn to look out for them. Awareness of your biases is the first step to understanding if your personal bias is contributing to the wrong decision.

New nurses may be overwhelmed by the transition from academics to clinical practice, leading to a task-oriented mindset and a common new nurse mistake ; this conflicts with critical thinking skills.

“Consider a patient whose blood pressure is low but who also needs to take a blood pressure medication at a scheduled time. A task-oriented nurse may provide the medication without regard for the patient’s blood pressure because medication administration is a task that must be completed,” Slaughter says. “A nurse employing critical thinking skills would address the low blood pressure, review the patient’s blood pressure history and trends, and potentially call the physician to discuss whether medication should be withheld.”

Fear and pride may also stand in the way of developing critical thinking skills. Your belief system and worldview provide comfort and guidance, but this can impede your judgment when you are faced with an individual whose belief system or cultural practices are not the same as yours. Fear or pride may prevent you from pursuing a line of questioning that would benefit the patient. Nurses with strong critical thinking skills exhibit:

- Learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of other nurses

- Look forward to integrating changes that improve patient care

- Treat each patient interaction as a part of a whole

- Evaluate new events based on past knowledge and adjust decision-making as needed

- Solve problems with their colleagues

- Are self-confident

- Acknowledge biases and seek to ensure these do not impact patient care

An Essential Skill for All Nurses

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

By using the strategies in this guide during your daily life and in your nursing role, you can intentionally improve your critical thinking abilities and be rewarded with better patient outcomes and potential career advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Critical Thinking in Nursing

How are critical thinking skills utilized in nursing practice.

Nursing practice utilizes critical thinking skills to provide the best care for patients. Often, the patient’s cause of pain or health issue is not immediately clear. Nursing professionals need to use their knowledge to determine what might be causing distress, collect vital information, and make quick decisions on how best to handle the situation.

How does nursing school develop critical thinking skills?

Nursing school gives students the knowledge professional nurses use to make important healthcare decisions for their patients. Students learn about diseases, anatomy, and physiology, and how to improve the patient’s overall well-being. Learners also participate in supervised clinical experiences, where they practice using their critical thinking skills to make decisions in professional settings.

Do only nurse managers use critical thinking?

Nurse managers certainly use critical thinking skills in their daily duties. But when working in a health setting, anyone giving care to patients uses their critical thinking skills. Everyone — including licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced nurse practitioners —needs to flex their critical thinking skills to make potentially life-saving decisions.

Meet Our Contributors

Crystal Slaughter, DNP, APRN, ACNS-BC, CNE

Crystal Slaughter is a core faculty member in Walden University’s RN-to-BSN program. She has worked as an advanced practice registered nurse with an intensivist/pulmonary service to provide care to hospitalized ICU patients and in inpatient palliative care. Slaughter’s clinical interests lie in nursing education and evidence-based practice initiatives to promote improving patient care.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN

Jenna Liphart Rhoads is a nurse educator and freelance author and editor. She earned a BSN from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing and an MS in nursing education from Northern Illinois University. Rhoads earned a Ph.D. in education with a concentration in nursing education from Capella University where she researched the moderation effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship of stress and GPA in military veteran nursing students. Her clinical background includes surgical-trauma adult critical care, interventional radiology procedures, and conscious sedation in adult and pediatric populations.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN

Nicholas McGowan is a critical care nurse with 10 years of experience in cardiovascular, surgical intensive care, and neurological trauma nursing. McGowan also has a background in education, leadership, and public speaking. He is an online learner who builds on his foundation of critical care nursing, which he uses directly at the bedside where he still practices. In addition, McGowan hosts an online course at Critical Care Academy where he helps nurses achieve critical care (CCRN) certification.

Brain, Decision Making and Mental Health pp 179–189 Cite as

Critical Thinking in Nursing

- Şefika Dilek Güven 3

- First Online: 02 January 2023

1066 Accesses

Part of the book series: Integrated Science ((IS,volume 12))

Critical thinking is an integral part of nursing, especially in terms of professionalization and independent clinical decision-making. It is necessary to think critically to provide adequate, creative, and effective nursing care when making the right decisions for practices and care in the clinical setting and solving various ethical issues encountered. Nurses should develop their critical thinking skills so that they can analyze the problems of the current century, keep up with new developments and changes, cope with nursing problems they encounter, identify more complex patient care needs, provide more systematic care, give the most appropriate patient care in line with the education they have received, and make clinical decisions. The present chapter briefly examines critical thinking, how it relates to nursing, and which skills nurses need to develop as critical thinkers.

Graphical Abstract/Art Performance

Critical thinking in nursing.

This painting shows a nurse and how she is thinking critically. On the right side are the stages of critical thinking and on the left side, there are challenges that a nurse might face. The entire background is also painted in several colors to represent a kind of intellectual puzzle. It is made using colored pencils and markers.

(Adapted with permission from the Association of Science and Art (ASA), Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN); Painting by Mahshad Naserpour).

Unless the individuals of a nation thinkers, the masses can be drawn in any direction. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Bilgiç Ş, Kurtuluş Tosun Z (2016) Birinci ve son sınıf hemşirelik öğrencilerinde eleştirel düşünme ve etkileyen faktörler. Sağlık Bilimleri ve Meslekleri Dergisi 3(1):39–47

Article Google Scholar

Kantek F, Yıldırım N (2019) The effects of nursing education on critical thinking of students: a meta-analysis. Florence Nightingale Hemşirelik Dergisi 27(1):17–25

Ennis R (1996) Critical thinking dispositions: their nature and assessability. Informal Logic 18(2):165–182

Riddell T (2007) Critical assumptions: thinking critically about critical thinking. J Nurs Educ 46(3):121–126

Cüceloğlu D (2001) İyi düşün doğru karar ver. Remzi Kitabevi, pp 242–284

Google Scholar

Kurnaz A (2019) Eleştirel düşünme öğretimi etkinlikleri Planlama-Uygulama ve Değerlendirme. Eğitim yayın evi, p 27

Doğanay A, Ünal F (2006) Eleştirel düşünmenin öğretimi. In: İçerik Türlerine Dayalı Öğretim. Ankara Nobel Yayınevi, pp 209–261

Scheffer B-K, Rubenfeld M-G (2000) A consensus statement on critical thinking in nursing. J Nurs Educ 39(8):352–359

Article CAS Google Scholar

Rubenfeld M-G, Scheffer B (2014) Critical thinking tactics for nurses. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, pp 5–6, 7, 19–20

Gobet F (2005) Chunking models of expertise: implications for education. Appl Cogn Psychol 19:183–204

Ay F-A (2008) Mesleki temel kavramlar. In: Temel hemşirelik: Kavramlar, ilkeler, uygulamalar. İstanbul Medikal Yayıncılık, pp 205–220

Birol L (2010) Hemşirelik bakımında sistematik yaklaşım. In: Hemşirelik süreci. Berke Ofset Matbaacılık, pp 35–45

Twibell R, Ryan M, Hermiz M (2005) Faculty perceptions of critical thinking in student clinical experiences. J Nurs Educ 44(2):71–79

The Importance of Critical Thinking in Nursing. 19 November 2018 by Carson-Newman University Online. https://onlinenursing.cn.edu/news/value-critical-thinking-nursing

Suzanne C, Smeltzer Brenda G, Bare Janice L, Cheever HK (2010) Definition of critical thinking, critical thinking process. Medical surgical nursing. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, pp 27–28

Profetto-McGrath J (2003) The relationship of critical thinking skills and critical thinking dispositions of baccalaureate nursing students. J Adv Nurs 43(6):569–577

Elaine S, Mary C (2002) Critical thinking in nursing education: literature review. Int J Nurs Pract 8(2):89–98

Brunt B-A (2005) Critical thinking in nursing: an integrated review. J Continuing Educ Nurs 36(2):60–67

Carter L-M, Rukholm E (2008) A study of critical thinking, teacher–student interaction, and discipline-specific writing in an online educational setting for registered nurses. J Continuing Educ Nurs 39(3):133–138

Daly W-M (2001) The development of an alternative method in the assessment of critical thinking as an outcome of nursing education. J Adv Nurs 36(1):120–130

Edwards S-L (2007) Critical thinking: a two-phase framework. Nurse Educ Pract 7(5):303–314

Rogal S-M, Young J (2008) Exploring critical thinking in critical care nursing education: a pilot study. J Continuing Educ Nurs 39(1):28–33

Worrell J-A, Profetto-McGrath J (2007) Critical thinking as an outcome of context-based learning among post RN students: a literature review. Nurse Educ Today 27(5):420–426

Morrall P, Goodman B (2013) Critical thinking, nurse education and universities: some thoughts on current issues and implications for nursing practice. Nurse Educ Today 33(9):935–937

Raymond-Seniuk C, Profetto-McGrath J (2011) Can one learn to think critically?—a philosophical exploration. Open Nurs J 5:45–51

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli University, Semra ve Vefa Küçük, Faculty of Health Sciences, Nursing Department, 2000 Evler Mah. Damat İbrahim Paşa Yerleşkesi, Nevşehir, Turkey

Şefika Dilek Güven

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Şefika Dilek Güven .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Stockholm, Sweden

Nima Rezaei

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Güven, Ş.D. (2023). Critical Thinking in Nursing. In: Rezaei, N. (eds) Brain, Decision Making and Mental Health. Integrated Science, vol 12. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15959-6_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15959-6_10

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-15958-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-15959-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (Explained W/ Examples)

Last updated on August 23rd, 2023

Critical thinking is a foundational skill applicable across various domains, including education, problem-solving, decision-making, and professional fields such as science, business, healthcare, and more.

It plays a crucial role in promoting logical and rational thinking, fostering informed decision-making, and enabling individuals to navigate complex and rapidly changing environments.

In this article, we will look at what is critical thinking in nursing practice, its importance, and how it enables nurses to excel in their roles while also positively impacting patient outcomes.

What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is a cognitive process that involves analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

It’s a mental activity that goes beyond simple memorization or acceptance of information at face value.

Critical thinking involves careful, reflective, and logical thinking to understand complex problems, consider various perspectives, and arrive at well-reasoned conclusions or solutions.

Key aspects of critical thinking include:

- Analysis: Critical thinking begins with the thorough examination of information, ideas, or situations. It involves breaking down complex concepts into smaller parts to better understand their components and relationships.

- Evaluation: Critical thinkers assess the quality and reliability of information or arguments. They weigh evidence, identify strengths and weaknesses, and determine the credibility of sources.

- Synthesis: Critical thinking involves combining different pieces of information or ideas to create a new understanding or perspective. This involves connecting the dots between various sources and integrating them into a coherent whole.

- Inference: Critical thinkers draw logical and well-supported conclusions based on the information and evidence available. They use reasoning to make educated guesses about situations where complete information might be lacking.

- Problem-Solving: Critical thinking is essential in solving complex problems. It allows individuals to identify and define problems, generate potential solutions, evaluate the pros and cons of each solution, and choose the most appropriate course of action.

- Creativity: Critical thinking involves thinking outside the box and considering alternative viewpoints or approaches. It encourages the exploration of new ideas and solutions beyond conventional thinking.

- Reflection: Critical thinkers engage in self-assessment and reflection on their thought processes. They consider their own biases, assumptions, and potential errors in reasoning, aiming to improve their thinking skills over time.

- Open-Mindedness: Critical thinkers approach ideas and information with an open mind, willing to consider different viewpoints and perspectives even if they challenge their own beliefs.

- Effective Communication: Critical thinkers can articulate their thoughts and reasoning clearly and persuasively to others. They can express complex ideas in a coherent and understandable manner.

- Continuous Learning: Critical thinking encourages a commitment to ongoing learning and intellectual growth. It involves seeking out new knowledge, refining thinking skills, and staying receptive to new information.

Definition of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an intellectual process of analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing is a vital cognitive skill that involves analyzing, evaluating, and making reasoned decisions about patient care.

It’s an essential aspect of a nurse’s professional practice as it enables them to provide safe and effective care to patients.

Critical thinking involves a careful and deliberate thought process to gather and assess information, consider alternative solutions, and make informed decisions based on evidence and sound judgment.

This skill helps nurses to:

- Assess Information: Critical thinking allows nurses to thoroughly assess patient information, including medical history, symptoms, and test results. By analyzing this data, nurses can identify patterns, discrepancies, and potential issues that may require further investigation.

- Diagnose: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data and collaboratively work with other healthcare professionals to formulate accurate nursing diagnoses. This is crucial for developing appropriate care plans that address the unique needs of each patient.

- Plan and Implement Care: Once a nursing diagnosis is established, critical thinking helps nurses develop effective care plans. They consider various interventions and treatment options, considering the patient’s preferences, medical history, and evidence-based practices.

- Evaluate Outcomes: After implementing interventions, critical thinking enables nurses to evaluate the outcomes of their actions. If the desired outcomes are not achieved, nurses can adapt their approach and make necessary changes to the care plan.

- Prioritize Care: In busy healthcare environments, nurses often face situations where they must prioritize patient care. Critical thinking helps them determine which patients require immediate attention and which interventions are most essential.

- Communicate Effectively: Critical thinking skills allow nurses to communicate clearly and confidently with patients, their families, and other members of the healthcare team. They can explain complex medical information and treatment plans in a way that is easily understood by all parties involved.

- Identify Problems: Nurses use critical thinking to identify potential complications or problems in a patient’s condition. This early recognition can lead to timely interventions and prevent further deterioration.

- Collaborate: Healthcare is a collaborative effort involving various professionals. Critical thinking enables nurses to actively participate in interdisciplinary discussions, share their insights, and contribute to holistic patient care.

- Ethical Decision-Making: Critical thinking helps nurses navigate ethical dilemmas that can arise in patient care. They can analyze different perspectives, consider ethical principles, and make morally sound decisions.

- Continual Learning: Critical thinking encourages nurses to seek out new knowledge, stay up-to-date with the latest research and medical advancements, and incorporate evidence-based practices into their care.

In summary, critical thinking is an integral skill for nurses, allowing them to provide high-quality, patient-centered care by analyzing information, making informed decisions, and adapting their approaches as needed.

It’s a dynamic process that enhances clinical reasoning , problem-solving, and overall patient outcomes.

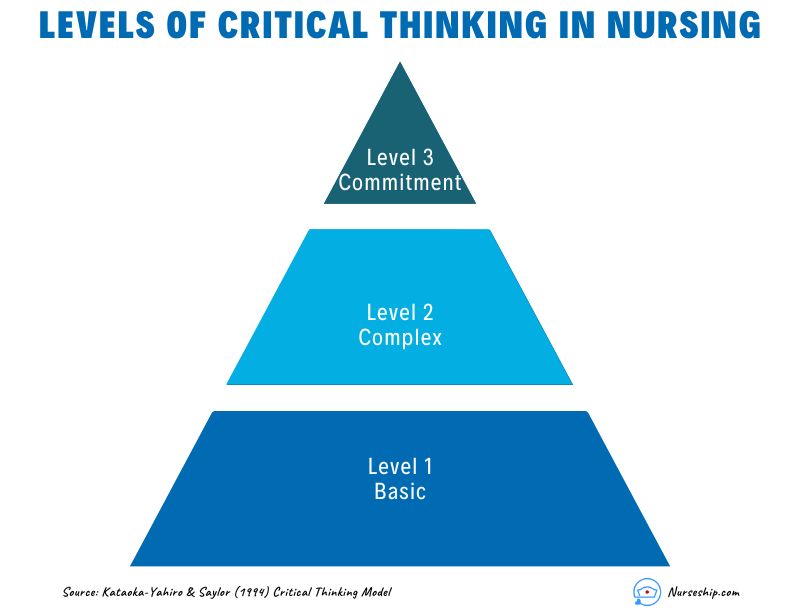

What are the Levels of Critical Thinking in Nursing?

The development of critical thinking in nursing practice involves progressing through three levels: basic, complex, and commitment.

The Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor model outlines this progression.

1. Basic Critical Thinking:

At this level, learners trust experts for solutions. Thinking is based on rules and principles. For instance, nursing students may strictly follow a procedure manual without personalization, as they lack experience. Answers are seen as right or wrong, and the opinions of experts are accepted.

2. Complex Critical Thinking:

Learners start to analyze choices independently and think creatively. They recognize conflicting solutions and weigh benefits and risks. Thinking becomes innovative, with a willingness to consider various approaches in complex situations.

3. Commitment:

At this level, individuals anticipate decision points without external help and take responsibility for their choices. They choose actions or beliefs based on available alternatives, considering consequences and accountability.

As nurses gain knowledge and experience, their critical thinking evolves from relying on experts to independent analysis and decision-making, ultimately leading to committed and accountable choices in patient care.

Why Critical Thinking is Important in Nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing for several crucial reasons:

Patient Safety:

Nursing decisions directly impact patient well-being. Critical thinking helps nurses identify potential risks, make informed choices, and prevent errors.

Clinical Judgment:

Nursing decisions often involve evaluating information from various sources, such as patient history, lab results, and medical literature.

Critical thinking assists nurses in critically appraising this information, distinguishing credible sources, and making rational judgments that align with evidence-based practices.

Enhances Decision-Making:

In nursing, critical thinking allows nurses to gather relevant patient information, assess it objectively, and weigh different options based on evidence and analysis.

This process empowers them to make informed decisions about patient care, treatment plans, and interventions, ultimately leading to better outcomes.

Promotes Problem-Solving:

Nurses encounter complex patient issues that require effective problem-solving.

Critical thinking equips them to break down problems into manageable parts, analyze root causes, and explore creative solutions that consider the unique needs of each patient.

Drives Creativity:

Nursing care is not always straightforward. Critical thinking encourages nurses to think creatively and explore innovative approaches to challenges, especially when standard protocols might not suffice for unique patient situations.

Fosters Effective Communication:

Communication is central to nursing. Critical thinking enables nurses to clearly express their thoughts, provide logical explanations for their decisions, and engage in meaningful dialogues with patients, families, and other healthcare professionals.

Aids Learning:

Nursing is a field of continuous learning. Critical thinking encourages nurses to engage in ongoing self-directed education, seeking out new knowledge, embracing new techniques, and staying current with the latest research and developments.

Improves Relationships:

Open-mindedness and empathy are essential in nursing relationships.

Critical thinking encourages nurses to consider diverse viewpoints, understand patients’ perspectives, and communicate compassionately, leading to stronger therapeutic relationships.

Empowers Independence:

Nursing often requires autonomous decision-making. Critical thinking empowers nurses to analyze situations independently, make judgments without undue influence, and take responsibility for their actions.

Facilitates Adaptability:

Healthcare environments are ever-changing. Critical thinking equips nurses with the ability to quickly assess new information, adjust care plans, and navigate unexpected situations while maintaining patient safety and well-being.

Strengthens Critical Analysis:

In the era of vast information, nurses must discern reliable data from misinformation.

Critical thinking helps them scrutinize sources, question assumptions, and make well-founded choices based on credible information.

How to Apply Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples)

Here are some examples of how nurses can apply critical thinking.

Assess Patient Data:

Critical Thinking Action: Carefully review patient history, symptoms, and test results.

Example: A nurse notices a change in a diabetic patient’s blood sugar levels. Instead of just administering insulin, the nurse considers recent dietary changes, activity levels, and possible medication interactions before adjusting the treatment plan.

Diagnose Patient Needs:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze patient data to identify potential nursing diagnoses.

Example: After reviewing a patient’s lab results, vital signs, and observations, a nurse identifies “ Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity ” due to the patient’s limited mobility.

Plan and Implement Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Develop a care plan based on patient needs and evidence-based practices.

Example: For a patient at risk of falls, the nurse plans interventions such as hourly rounding, non-slip footwear, and bed alarms to ensure patient safety.

Evaluate Interventions:

Critical Thinking Action: Assess the effectiveness of interventions and modify the care plan as needed.

Example: After administering pain medication, the nurse evaluates its impact on the patient’s comfort level and considers adjusting the dosage or trying an alternative pain management approach.

Prioritize Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Determine the order of interventions based on patient acuity and needs.

Example: In a busy emergency department, the nurse triages patients by considering the severity of their conditions, ensuring that critical cases receive immediate attention.

Collaborate with the Healthcare Team:

Critical Thinking Action: Participate in interdisciplinary discussions and share insights.

Example: During rounds, a nurse provides input on a patient’s response to treatment, which prompts the team to adjust the care plan for better outcomes.

Ethical Decision-Making:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze ethical dilemmas and make morally sound choices.

Example: When a terminally ill patient expresses a desire to stop treatment, the nurse engages in ethical discussions, respecting the patient’s autonomy and ensuring proper end-of-life care.

Patient Education:

Critical Thinking Action: Tailor patient education to individual needs and comprehension levels.

Example: A nurse uses visual aids and simplified language to explain medication administration to a patient with limited literacy skills.

Adapt to Changes:

Critical Thinking Action: Quickly adjust care plans when patient conditions change.

Example: During post-operative recovery, a nurse notices signs of infection and promptly informs the healthcare team to initiate appropriate treatment adjustments.

Critical Analysis of Information:

Critical Thinking Action: Evaluate information sources for reliability and relevance.

Example: When presented with conflicting research studies, a nurse critically examines the methodologies and sample sizes to determine which study is more credible.

Making Sense of Critical Thinking Skills

What is the purpose of critical thinking in nursing.

The purpose of critical thinking in nursing is to enable nurses to effectively analyze, interpret, and evaluate patient information, make informed clinical judgments, develop appropriate care plans, prioritize interventions, and adapt their approaches as needed, thereby ensuring safe, evidence-based, and patient-centered care.

Why critical thinking is important in nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing because it promotes safe decision-making, accurate clinical judgment, problem-solving, evidence-based practice, holistic patient care, ethical reasoning, collaboration, and adapting to dynamic healthcare environments.

Critical thinking skill also enhances patient safety, improves outcomes, and supports nurses’ professional growth.

How is critical thinking used in the nursing process?

Critical thinking is integral to the nursing process as it guides nurses through the systematic approach of assessing, diagnosing, planning, implementing, and evaluating patient care. It involves:

- Assessment: Critical thinking enables nurses to gather and interpret patient data accurately, recognizing relevant patterns and cues.

- Diagnosis: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data, identify nursing diagnoses, and differentiate actual issues from potential complications.

- Planning: Critical thinking helps nurses develop tailored care plans, selecting appropriate interventions based on patient needs and evidence.

- Implementation: Nurses make informed decisions during interventions, considering patient responses and adjusting plans as needed.

- Evaluation: Critical thinking supports the assessment of patient outcomes, determining the effectiveness of intervention, and adapting care accordingly.

Throughout the nursing process , critical thinking ensures comprehensive, patient-centered care and fosters continuous improvement in clinical judgment and decision-making.

What is an example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice?

An example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice could be:

A nurse is caring for a patient with a complex medical history who is experiencing a new set of symptoms. The nurse carefully reviews the patient’s history, recent test results, and medication list.

While discussing the case with the healthcare team, the nurse realizes that the current treatment plan might not be addressing all aspects of the patient’s condition.

Instead of simply following the established protocol, the nurse independently considers alternative approaches based on their assessment.

The nurse proposes a modification to the treatment plan, citing the rationale and evidence supporting the change.

This demonstrates independent thinking by critically evaluating the situation, challenging assumptions, and advocating for a more personalized and effective patient care approach.

How to use Costa’s level of questioning for critical thinking in nursing?

Costa’s levels of questioning can be applied in nursing to facilitate critical thinking and stimulate a deeper understanding of patient situations. The levels of questioning are as follows:

- 15 Attitudes of Critical Thinking in Nursing (Explained W/ Examples)

- Nursing Concept Map (FREE Template)

- Clinical Reasoning In Nursing (Explained W/ Example)

- 8 Stages Of The Clinical Reasoning Cycle

- How To Improve Critical Thinking Skills In Nursing? 24 Strategies With Examples

- What is the “5 Whys” Technique?

- What Are Socratic Questions?

Critical thinking in nursing is the foundation that underpins safe, effective, and patient-centered care.

Critical thinking skills empower nurses to navigate the complexities of their profession while consistently providing high-quality care to diverse patient populations.

Reading Recommendation

Potter, P.A., Perry, A.G., Stockert, P. and Hall, A. (2013) Fundamentals of Nursing

Comments are closed.

Medical & Legal Disclaimer

All the contents on this site are for entertainment, informational, educational, and example purposes ONLY. These contents are not intended to be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or practice guidelines. However, we aim to publish precise and current information. By using any content on this website, you agree never to hold us legally liable for damages, harm, loss, or misinformation. Read the privacy policy and terms and conditions.

Privacy Policy

Terms & Conditions

© 2024 nurseship.com. All rights reserved.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Margaret McCartney:...

Nurses are critical thinkers

Rapid response to:

Margaret McCartney: Nurses must be allowed to exercise professional judgment

- Related content

- Article metrics

- Rapid responses

Rapid Response:

The characteristic that distinguishes a professional nurse is cognitive rather than psychomotor ability. Nursing practice demands that practitioners display sound judgement and decision-making skills as critical thinking and clinical decision making is an essential component of nursing practice. Nurses’ ability to recognize and respond to signs of patient deterioration in a timely manner plays a pivotal role in patient outcomes (Purling & King 2012). Errors in clinical judgement and decision making are said to account for more than half of adverse clinical events (Tomlinson, 2015). The focus of the nurse clinical judgement has to be on quality evidence based care delivery, therefore, observational and reasoning skills will result in sound, reliable, clinical judgements. Clinical judgement, a concept which is critical to the nursing can be complex, because the nurse is required to use observation skills, identify relevant information, to identify the relationships among given elements through reasoning and judgement. Clinical reasoning is the process by which nurses observe patients status, process the information, come to an understanding of the patient problem, plan and implement interventions, evaluate outcomes, with reflection and learning from the process (Levett-Jones et al, 2010). At all times, nurses are responsible for their actions and are accountable for nursing judgment and action or inaction.

The speed and ability by which the nurses make sound clinical judgement is affected by their experience. Novice nurses may find this process difficult, whereas the experienced nurse should rely on her intuition, followed by fast action. Therefore education must begin at the undergraduate level to develop students’ critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills. Clinical reasoning is a learnt skill requiring determination and active engagement in deliberate practice design to improve performance. In order to acquire such skills, students need to develop critical thinking ability, as well as an understanding of how judgements and decisions are reached in complex healthcare environments.

As lifelong learners, nurses are constantly accumulating more knowledge, expertise, and experience, and it’s a rare nurse indeed who chooses to not apply his or her mind towards the goal of constant learning and professional growth. Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on the Future of Nursing, stated, that nurses must continue their education and engage in lifelong learning to gain the needed competencies for practice. American Nurses Association (ANA), Scope and Standards of Practice requires a nurse to remain involved in continuous learning and strengthening individual practice (p.26)

Alfaro-LeFevre, R. (2009). Critical thinking and clinical judgement: A practical approach to outcome-focused thinking. (4th ed.). St Louis: Elsevier

The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health, (2010). https://campaignforaction.org/resource/future-nursing-iom-report

Levett-Jones, T., Hoffman, K. Dempsey, Y. Jeong, S., Noble, D., Norton, C., Roche, J., & Hickey, N. (2010). The ‘five rights’ of clinical reasoning: an educational model to enhance nursing students’ ability to identify and manage clinically ‘at risk’ patients. Nurse Education Today. 30(6), 515-520.

NMC (2010) New Standards for Pre-Registration Nursing. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council.

Purling A. & King L. (2012). A literature review: graduate nurses’ preparedness for recognising and responding to the deteriorating patient. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(23–24), 3451–3465

Thompson, C., Aitken, l., Doran, D., Dowing, D. (2013). An agenda for clinical decision making and judgement in nursing research and education. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50 (12), 1720 - 1726 Tomlinson, J. (2015). Using clinical supervision to improve the quality and safety of patient care: a response to Berwick and Francis. BMC Medical Education, 15(103)

Competing interests: No competing interests

Critical Thinking

High quality, safe patient care is dependent upon the healthcare provider’s ability to reason, think, and make judgments about care. Critical thinking, clinical reasoning and judgment are integral to quality clinical decisions and actions. Today’s healthcare landscape has transitioned towards an environment where patients are more medically complex, an aging population with chronic illness, and increased socioeconomic diversity. In order to provide quality patient-centered care, nurses need to develop CT skills in order to provide patients with expert care (Brunt, 2005).

Developing CT is an ethical responsibility of professional nursing practice, and a component for sound clinical judgments and safe decision-making. Thinking in a logical, systematic way, being open to questioning current practice, and reflecting on one’s practice regularly are some key features that strengthen nurses’ CT skills.

The quality of clinical decision-making is influenced by a number of factors, including experience, level of education, time pressures, and also the culture of the nursing unit (Johansson, Pilhammar, & Willman 2009). Developing critical thinking skills has the potential to improve personal practice and patient outcomes.

Critical thinking (CT) is a process used for problem-solving and decision-making. CT is a broad term that encompasses clinical reasoning and clinical judgment. Clinical reasoning (CR) is a process of analyzing information that is relevant to patient care. When data is analyzed, clinical judgments about care is made. The process of analyzing the data, making decisions is the result of CT—thinking critically throughout the entire patient situation, weighing all relevant options and using CT skills to make the best decision for the patient.

While many definitions have been cited for CT (see below), there is a general agreement that CT is a purposeful action that includes analysis, logical reasoning, intuition, and reflection. Making a concerted effort to critically think during patient care leads to safe, effective decisions. Developing CT skills is key for all nurses, they spend the most time with patients, and are able to recognize subtle changes in their patients and are positioned to make quick, precise decisions, often lifesaving. Using effective CT skills allows nurses to shape the outcome of a patient’s experience with the healthcare system.

The concept of critical thinking has been an integral part of professional frameworks for generations, yet scholars still debate a universal accepted definition. Dozens of CT definitions have been published, with each of them sharing some common features, such as reflection, contemplation, holism, and intuition. The list below shares a variety of CT definitions:

“The rational examination of ideas, inferences, assumptions, principles, arguments, conclusions, ideas, statement beliefs and action” (Bandman & Bandman, 1995, p. 7)

A reflective skepticism; “reflecting on the assumptions underlying our and others’ ideas and actions and contemplative alternative ways of thinking and living” (Brookfield, 1987, p. 18)

“The process of purposeful self-regulatory judgment . . . gives reasoned consideration to evidence, context, conceptualization, methods and criteria: (Facione, 2006, p. 21)

“Reasonable and reflective thinking that is focused upon deciding what to believe or do” (Kennedy, Fisher, & Ennis, 1991, p.46)

“An investigation whose purpose is to explore a situation, phenomenon, question, or problem to arrive at a hypothesis or conclusion about it that integrates all available information and that, therefore, can be convincingly justified” (Kurfiss, 1988, p. 37)

“The propensity and skill to engage in an activity with reflective skepticism” (McPeck, 1961, p. 8)

“The deliberative nonlinear process of collecting, interpreting, analyzing, drawing conclusions about, presenting and evaluating information that is both factual and belief based” (National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission, 2000, p. 8)

“A unique kind of purposeful thinking in which the thinker systematically and habitually imposes criteria and intellectual standards upon the thinking, taking charge of the construction of thinking, guiding the construction of the thinking according to the standard, and assessing the effectiveness of the thinking according to the purpose, the criteria and the standards” (Paul, 1993, p. 21)

“In nursing . . . an essential component of professional accountability and quality nursing care [that exhibits] confidence, contextual perspective, creativity, flexibility, inquisitiveness, intellectual integrity, intuition, open-mindedness, perseverance and reflection.” (Scheffer & Ruberfeld, 2000, p. 357)

Concepts Related to Critical Thinking

Clinical Reasoning

- A process where nurses integrate and analyze patient data to make decisions about patient care (Simmons, Lanuza, Fonteyn, & Hicks, 2003)

Clinical Decision-Making

- A process of choosing between different options or alternatives (Thompson & Stapley, 2011)

Clinical Judgment

- A cognitive process used to make judgments based on patient data and cues. Nurses interpret a patient’s concerns, needs, and health problems for proper decision-making (Tanner, 2006, p. 204)

- Outcome of critical thinking in nursing practice; judgments begin with the end goal in mind; outcomes are met, involves evidence (Pesut, 2001)

Logical Reasoning

- Arriving at a conclusion based on relatively small amounts of knowledge and/or information (Westcott, 1968)

- “Drawing inferences or conclusions that are supported in or justified by evidence (Alfaro-LeFevre, 2015, p. 232)

- A purposeful analysis of one’s current and past actions (Schon, 1987)

Experience and Clinical Reasoning

According to Benner’s (1984) novice to expert model, expert nurses have an intuitive grasp of their patients’ problems, their approach is fluid, flexible, and proficient. Compared to novice nurses, they are more task oriented and require frequent verbal and physical cues to provide care.

Novice nurses are challenged with overcoming a knowledge gap, leading to less effective decisions and actions. Compared to experienced nurses, who are challenged with traditional thinking, leading to less effective clinical judgments and decisions (Cappelletti et al., 2014). Successful CR and decision-making require a balance of intuition and evidence-based thinking to make effective clinical decisions (Simmons et al., 2003).

Andersson et al. (2012) found nurses who were specialized in their setting (more experience) used a more holistic approach to making decisions (p. 876), compared to less experienced nurses who used a “task-and action-oriented approach” (p. 873). Gaining experience and knowledge is one way to improve thinking and decision-making, though improving CT skills can close the gap. Being open-minded, self-aware, and reflective offers nurses important information that can improve CR and decision-making. Clinical judgment (akin to CR) improves over time with nurses who uses reflection as a guide for decisions and actions (Cappelletti et al., 2014).

Critical Thinking and Clinical Decision-Making

Lee et al. (2017) conducted an integrated review on nine studies to determine whether effective CT impacted clinical decision-making. Four studies found CT impacted decision-making, though five studies did not find a correlation. Due to poor study designs, Lee et al. (2017) could not come to a clear decision on whether there was as significant correlation.

CT continues to be an important factor for problem-solving, regardless if studies can confirm a correlation to decision-making. Developing CT skills, such as reflection, intuition, and logical reasoning, are essential behaviors that lead to a patient-centered approach. Nurses who stop and think about what worked for a patient in the past, may consider the same option again, or may choose an alternative. Considering all possibilities with the patient’s best interest in mind is part of CT and making clinical decisions.

Researchers will continue to study the impact of CT on nursing care. Nurse educators will continue emphasize CT in the curriculum and assist students in developing CT skills throughout all levels of education as they offer students tools and methods for problem-solving.

Rubenfeld and Scheffer (2001) explain the essence of CT in nursing practice:

Critical thinking in nursing is an essential component of professional accountability and quality nursing care. Critical thinkers exhibit these habits of the mind: confidence, contextual perspective, creativity, flexibility, inquisitiveness, intellectual integrity, intuition, open-mindedness, perseverance, and reflection. Critical thinkers in nursing practice the cognitive skills of analyzing, applying standards, discriminating, information seeking, logical reasoning, predicting and transforming knowledge (2001, p. 125).

Standards of Practice

Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are weaved throughout the Nursing Scope and Standards of Practice and Code of Ethics (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2021). The nursing process itself, Standards 1-6, are essentially a tool used for clinical reasoning. The standards require core cognitive competencies and guide nurses to use patient data to make effective clinical decisions.

The Essentials

Clinical Judgement is one of the eight featured concepts within The Essentials (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2021, p.12). The process of clinical judgement, as earlier in this section, is the outcome of critical thinking.

The Essentials explains how a liberal arts education is critical to exposing nurses to a broad worldview, giving them a holistic perspective that engages them in promoting health equity and social justice, , and “forms the basis for clinical reasoning and subsequent clinical judgments” (AACN, 2021, p. ).

Problem-Solving A pproaches

Reflective thinking.

Reflection is a powerful tool for recognizing errors in judgment, questioning one’s response, and ultimately improving outcomes. Below are two practice examples that illustrate the power of reflective thinking with interprofessional communication and patient care:

Novice and senior nurse communication

- Problem: A novice nurse is struggling with inserting IVs just about every shift. One day, the nurse asks the same more experienced nurse for help again. The nurse listens though does not turn around to face the nurse when questioned, and responds in a swift, aggressive way, “I’m swamped, we have no aides today and I’m falling behind with everything. I’ll help you when I get time, but it’s going to be a while.”

- Impact: The nurse’s patient is at risk for injury without an IV line. The patient may be upset and unsatisfied with care knowing the IV was out for an extended period of time. The nurse feels dejected, does not feel like she is a valued team member, and loses further confidence in her abilities. She considers quitting her job or transferring to another unit.

- Reflection: The experienced nurse realizes she was not empathetic to the nurse’s needs and impatient and aggressive in her response. She realizes the nurse is new and doesn’t have much confidence in her skills yet. She also knows the nurse is probably disappointed in the lack of teamwork and camaraderie. Most of all, she feels bad about disrespecting her coworker.

- Impact of reflection : After reflection of the situation, the nurse apologizes for her poor behavior. She states she will work with her each shift they work together, she will share personal tips and review educational materials. Additionally, she will offer to have her observe her IV insertions until she has mastered the skill. She will also make sure the new nurse feels like she is part of the team, not just the new nurse.

Shift report

- Problem: The oncoming nurse enters his patient room for the first time and finds the foley bag is full and the patient is complaining of abdominal discomfort.

- Impact: The patient is at risk for infection and may be disappointed with the quality of nursing care.

- Reflection: The oncoming nurse realizes there is always one or two problems or inconsistencies when he assesses his patients for the first time. He knows the outgoing nurses are skilled and provide quality care and considers another reason for the errors. After thinking about this for a while, he believes the process for shift report can help reduce change of shift errors. The nurse realizes there needs to be a better way for sharing patient information during change of shift.

- Impact of reflection: The nurse researches evidence-based practices to improve safety and quality during shift change. The nurse shares a copy of the review article on bedside report with his manager. The nurse offers to be a change champion on the unit to implement a new process for shift report.

L ong-term impact of reflection :

- Improved team cohesiveness, nurse retention and job satisfaction

- Improved patient satisfaction experience and quality of care, leading to higher insurance reimbursement

Glynn (2012) states reflective thinking enhances clinical judgment and gives nurses the opportunity to learn from actual or perceived errors. In regard to the communication scenario, it’s through reflection that nurses can think about their behaviors and responses. Reflect on the message for clarity, and whether it was shared in an empathetic and respective way.

As discussed in the communication chapter, poor communication is the number one reason for medication errors and sentinel events. Through reflection, miscommunication can be identified, solutions found, and implemented. In order for this process to come to fruition, nurses must take the initiative to reflect on their practice.

Creative Thinking

Creative thinking helps nurses generate alternative approaches to clinical decision-making. This type of thinking works especially well with medically complex patients, where care needs to be individualized to reach desired outcomes.

Akin to the concept of “thinking outside the box”, finding a novel approach to patient care prevents traditional, stagnant thinking. Choosing alternatives based solely on creative thinking can negatively impact outcomes unless it is paired with the skill of critical thinking. Critical thinking requires the nurse to view the patient holistically,

Nurses access knowledge unconsciously and trust this information as fact. Often referred to as a “gut feeling”, intuition comes naturally. Intuition is not a tool that is sought out at will, instead the knowledge emerges naturally during a care experience, resulting in firm actions and decisions. Intuition is a measure of professional expertise (Smith, Thurkettle, & Cruz, 2004), a type of clinical judgement that develops over time (Benner, 1984). Since this knowledge is considered intangible or irrelevant, some disregard it, though many studies have shown its positive influence in making accurate decisions and improving the quality of care (Robert, Tilley & Petersen, 2014).

- Nurses will recognize something about their patient that they can’t explain, and will make decisions on care without concrete evidence to back up their actions. Such actions can be lifesaving (Billay, Myrick, Luhanga & Yonge 2007). Each clinical experience acts as a learning experience for which lessons are learned and applied to the next experience (McCutcheon & Pincombe, 2001).

- Holtslander (2008) states Carper’s (1978) seminal work on the fundamental ways of knowing was published as a reaction to the overemphasis of empirical (scientific) knowledge in nursing practice. One of the four ways of knowing , called aesthetic knowing , explains the component of art within nursing practice, an, awareness of the patient, viewing the patient as unique. This viewpoint allows nurses to consider more than just empirical knowledge to guide practice.

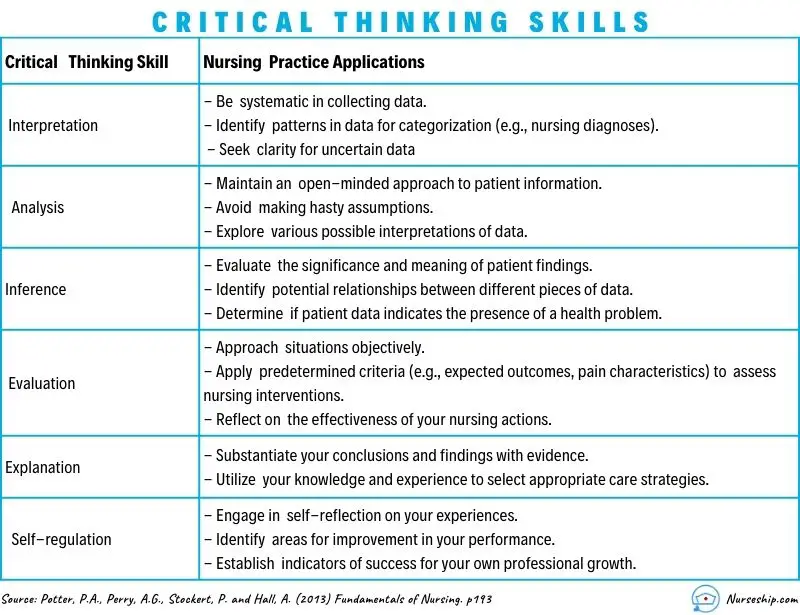

Critical Thinking Skills

As discussed earlier, CT encompasses a broad range of reasoning skills that lead to effective decision-making. Through the process of clinical reasoning and judgment, nurses make best choice after assembling and analyzing patient data.

White (2003) studied senior baccalaureate nurses and found the following five themes were essential to developing clinical decision-making skills:

- Gaining confidence in clinical skills

- Building relationships with staff

- Connecting with patients

- Gaining comfort in self as a nurse

- Understanding the clinical picture

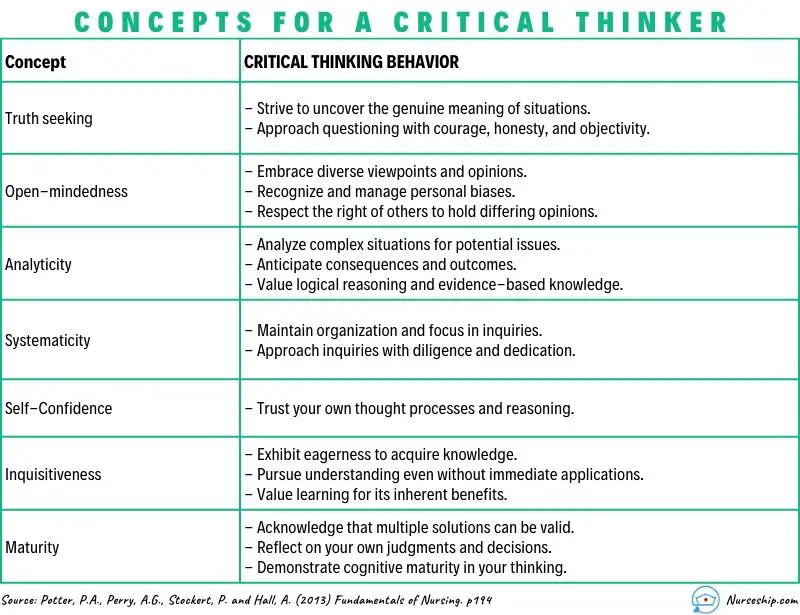

Scheffer and Rubenfeld (2000) found CT is comprised of affective and cognitive components. Affective components refer to an individual’s feelings and attitudes, and cognitive components refer to thought processes. The CT components include 10 habits of the mind (affective components) and seven skills (cognitive components), as follows:

Habits of the mind

- Confidence : assurance of one’s reasoning abilities

- C ontextual perspective : considerate of the whole situation, including relationships, background and environment relevant to some happening

- C re a tivity : intellectual inventiveness used to generate, discover, or restructure ideas; imagining alternatives

- F lexibility : capacity to adapt, accommodate, modify or change thoughts, ideas, and behaviors

- I nquisitiveness : an eagerness to know by seeking knowledge and understanding through observation and thoughtful questioning in order to explore possibilities and alternatives

- I ntellectual integrity : seeking the truth through sincere, honest processes, even if the results are contrary to one’s assumptions and beliefs

- I ntuition : insightful sense of knowing without conscious use of reason

- O pen-mindedness : a viewpoint characterized by being receptive to divergent views and sensitive to one’s biases

- P erseverance : pursuit of a course with determination to overcome obstacles

- R eflection : contemplation upon a subject, especially one’s assumptions and thinking for the purposes of deeper understanding and self-evaluation (Scheffer & Rubenfeld, 2000, p. 358)

- Analyzing : separating or breaking a whole into parts to discover their nature, function and relationships

- A pplying standards : judging according to established personal, professional or social rules or criteria

- D iscriminating : recognizing differences and similarities among things or situations and distinguishing carefully as to category or rank

- I nformation seeking : searching for evidence, facts or knowledge by identifying relevant sources and gathering objective, subjective, historical, and current data from those sources

- L ogical reasoning : drawing inferences or conclusions that are supported in or justified by evidence

- P redicting : envisioning a plan and its consequences

- T ransforming knowledge : changing or converting the condition, nature, form, or function of concepts among contexts (Scheffer & Rubenfeld, 2000, p. 358)

Development of CT is a lifelong process that requires nurses to be self-aware, and to use knowledge and experience as a tool to become a critical thinker. As nurses move along the continuum from novice to expert, one’s competence and ability to critically think will expand (Brunt, 2005).

- Transitions to Professional Nursing Practice. Authored by : Jamie Murphy. Provided by : SUNY Delhi. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-delhi-professionalnursing . License : CC BY: Attribution

Privacy Policy

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Revalidation

CPD Previous Next

Applying critical thinking to nursing, bob price healthcare education and practice development consultant, surrey, england.

Critical thinking and writing are skills that are not easy to acquire. The term ‘critical’ is used differently in social and clinical contexts. Nursing students need time to master the inquisitive and ruminative aspects of critical thinking that are required in academic environments. This article outlines what is meant by critical thinking in academic settings, in relation to both theory and reflective practice. It explains how the focus of a question affects the sort of critical thinking required and offers two taxonomies of learning, to which students can refer when analysing essay requirements. The article concludes with examples of analytical writing in reference to theory and reflective practice.

Nursing Standard . 29, 51, 49-60. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.51.49.e10005

All articles are subject to external double-blind peer review and checked for plagiarism using automated software.

Received: 23 February 2015

Accepted: 10 April 2015

education - students - study skills - studying - academic assignments - continuing professional development - CPD - clinical reasoning - critical appraisal - learning outcomes - reflection - reflective practice

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

19 August 2015 / Vol 29 issue 51

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Applying critical thinking to nursing

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Applying critical thinking to nursing

Affiliation.

- 1 Surrey, England.

- PMID: 26285997

- DOI: 10.7748/ns.29.51.49.e10005

Critical thinking and writing are skills that are not easy to acquire. The term 'critical' is used differently in social and clinical contexts. Nursing students need time to master the inquisitive and ruminative aspects of critical thinking that are required in academic environments. This article outlines what is meant by critical thinking in academic settings, in relation to both theory and reflective practice. It explains how the focus of a question affects the sort of critical thinking required and offers two taxonomies of learning, to which students can refer when analysing essay requirements. The article concludes with examples of analytical writing in reference to theory and reflective practice.

Keywords: Course assignment work; critical reflection; critical thinking; learning; nurse assessment; nurse education; reflection; reflective practice.

Publication types

- Education, Nursing*

- Problem Solving*

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Improving nurses’ readiness for evidence-based practice in critical care units: results of an information literacy training program

Jamileh farokhzadian.

1 Nursing Research Center, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

2 Department of Community Health Nursing, Razi Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Somayeh Jouparinejad

3 Health in Disasters and Emergencies Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Farhad Fatehi

4 School of Psychological Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

5 Centre for Online Health, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

Fatemeh Falahati-Marvast

6 Health Information Sciences Department, Faculty of Management and Medical Information Sciences, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Associated Data

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

One of the most important prerequisites for nurses’ readiness to implement Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) is to improve their information literacy skills. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of a training program on nurses’ information literacy skills for EBP in critical care units.

In this interventional study, 60 nurses working in critical care units of hospitals affiliated to Kerman University of Medical Sciences were randomly assigned into the intervention or control groups. The intervention group was provided with information literacy training in three eight-hour sessions over 3 weeks. Data were collected using demographic and information literacy skills for EBP questionnaires before and 1 month after the intervention.

At baseline, the intervention and control groups were similar in terms of demographic characteristics and information literacy skills for EBP. The training program significantly improved all dimensions of information literacy skills of the nurses in the intervention group, including the use of different information resources (3.43 ± 0.48, p < 0.001), information searching skills and the use of different search features (3.85 ± 0.67, p < 0.001), knowledge about search operators (3.74 ± 0.14, p < 0.001), and selection of more appropriate search statement ( x 2 = 50.63, p = 0.001) compared with the control group.

Conclusions

Nurses can learn EBP skills and apply research findings in their nursing practice in order to provide high-quality, safe nursing care in clinical settings. Practical workshops and regular training courses are effective interventional strategies to equip nurses with information literacy skills so that they can apply these skills to their future nursing practice.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has recommended that Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) be used in 90% of clinical decisions by 2020 [ 1 ]. EBP has become a popular buzzword in the healthcare industry [ 1 , 2 ]. This concept is defined as a problem-solving process in clinical decision making, which combines best research evidence with clinical expertise, patient preference, and clinical guidelines. EBP is required to improve quality of care, patient outcomes, and cost effectiveness of care [ 2 , 3 ]. It is a gold standard that provides a framework for delivery of safe and compassionate care. EBP is not only the use of research results but also includes all aspects of nursing knowledge, attitudes, skills and self-efficacy. It is considered as an essential skill for nurses to use the best scientific evidence when designing and implementing healthcare programs as well as when applying the available research evidence in decision-making process [ 2 ].

Critical care nurses are responsible for the assessment of patients and provision of care in critical care units. Critical care nurses need expertise and evidence to recognize clinical changes and prevent complications in patients. EBP should be applied to provide better care for patients in critical care units [ 4 ]. Policymakers expect nurses to make decisions based on the most recent evidence [ 5 ]. Therefore, nurses must be equipped with information literacy skills to obtain research findings and up-to-date information [ 6 , 7 ]. Information literacy is fundamental for successful implementation of EBP, and nurses should learn and improve their search and retrieval skills in order to obtain best evidence and information for providing sympathetic, safe and ethical care [ 7 – 11 ].