- Library of Congress

- Research Guides

- Law Library

Legal Research: A Guide to Case Law

Introduction.

- Federal Court Decisions

- State Court Decisions

- Decisions by Topic (Digests)

- Databases and Online Resources

- Dockets and Court Filings

Law Library : Ask a Librarian

Have a question? Need assistance? Use our online form to ask a librarian for help.

Authors: Emily Carr, Senior Legal Reference Librarian, Law Library of Congress

Elizabeth Osborne, Senior Legal Reference Librarian, Law Library of Congress

Editors: Barbara Bavis, Bibliographic and Research Instruction Librarian, Law Library of Congress

Anna Price, Legal Reference Librarian, Law Library of Congress

Note: This guide is adapted from a research guide originally published on the Law Library's website .

Created: September 9, 2019

Last Updated: February 1, 2023

Each branch of government produces a different type of law. Case law is the body of law developed from judicial opinions or decisions over time (whereas statutory law comes from legislative bodies and administrative law comes from executive bodies). This guide introduces beginner legal researchers to resources for finding judicial decisions in case law resources. Coverage includes brief explanations of the court systems in the United States; federal and state case law reporters; basic Bluebook citation style for court decisions; digests; and online access to court decisions.

Court Systems and Decisions

| One court that creates binding precedent on all courts below. |

| Thirteen circuits (12 regional and 1 for the federal circuit) that create binding precedent on the District Courts in their region, but not binding on courts in other circuits and not binding on the Supreme Court. |

| Ninety-four districts (1 district court and 1 bankruptcy court each) plus the U.S. Court of International Trade and the U.S. Court of Federal Claims. District Courts must adhere to the precedents set by the Supreme Court and the Circuit Court of Appeals in which they sit. |

The United States has parallel court systems, one at the federal level, and another at the state level. Both systems are divided into trial courts and appellate courts. Generally, trial courts determine the relevant facts of a dispute and apply law to these facts, while appellate courts review trial court decisions to ensure the law was applied correctly.

Stare Decisis (Precedent)

In Latin, stare decisis means "to stand by things decided." In the U.S. legal system, this Latin phrase represents the "doctrine of precedent, under which a court must follow earlier decisions when the same points arise again in litigation." ( Black's Law Dictionary , 11th ed.) Typically, a court will deviate from precedent only if there is a compelling reason. Under "vertical" stare decisis , the decisions of the highest court in a jurisdiction create mandatory precedent that must be followed by lower courts in that jurisdiction. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court creates binding precedent that all other federal courts must follow (and that all state courts must follow on questions of constitutional interpretation). Similarly, the highest court in a state creates mandatory precedent for the lower state courts below it. Intermediate appellate courts (such as the federal circuit courts of appeal) create mandatory precedent for the courts below them. A related concept is "horizontal" stare decisis , whereby a court applies its own prior decisions to similar facts before it in the future.

Case Law Reporters

Decisions are published in serial print publications called “reporters,” and are also published electronically. Reporters are discussed in greater detail under " Federal Court Decisions " and " State Court Decisions ." Information about how to cite decisions in a reporter is discussed under " Citations ."

- Next: Federal Court Decisions >>

- Last Updated: Mar 29, 2023 2:13 PM

- URL: https://guides.loc.gov/case-law

Business development

- Billing management software

- Court management software

- Legal calendaring solutions

Practice management & growth

- Project & knowledge management

- Workflow automation software

Corporate & business organization

- Business practice & procedure

Legal forms

- Legal form-building software

Legal data & document management

- Data management

- Data-driven insights

- Document management

- Document storage & retrieval

Drafting software, service & guidance

- Contract services

- Drafting software

- Electronic evidence

Financial management

- Outside counsel spend

Law firm marketing

- Attracting & retaining clients

- Custom legal marketing services

Legal research & guidance

- Anywhere access to reference books

- Due diligence

- Legal research technology

Trial readiness, process & case guidance

- Case management software

- Matter management

Recommended Products

Conduct legal research efficiently and confidently using trusted content, proprietary editorial enhancements, and advanced technology.

Accelerate how you find answers with powerful generative AI capabilities and the expertise of 650+ attorney editors. With Practical Law, access thousands of expertly maintained how-to guides, templates, checklists, and more across all major practice areas.

A business management tool for legal professionals that automates workflow. Simplify project management, increase profits, and improve client satisfaction.

- All products

Tax & Accounting

Audit & accounting.

- Accounting & financial management

- Audit workflow

- Engagement compilation & review

- Guidance & standards

- Internal audit & controls

- Quality control

Data & document management

- Certificate management

- Data management & mining

- Document storage & organization

Estate planning

- Estate planning & taxation

- Wealth management

Financial planning & analysis

- Financial reporting

Payroll, compensation, pension & benefits

- Payroll & workforce management services

- Healthcare plans

- Billing management

- Client management

- Cost management

- Practice management

- Workflow management

Professional development & education

- Product training & education

- Professional development

Tax planning & preparation

- Financial close

- Income tax compliance

- Tax automation

- Tax compliance

- Tax planning

- Tax preparation

- Sales & use tax

- Transfer pricing

- Fixed asset depreciation

Tax research & guidance

- Federal tax

- State & local tax

- International tax

- Tax laws & regulations

- Partnership taxation

- Research powered by AI

- Specialized industry taxation

- Credits & incentives

- Uncertain tax positions

A powerful tax and accounting research tool. Get more accurate and efficient results with the power of AI, cognitive computing, and machine learning.

Provides a full line of federal, state, and local programs. Save time with tax planning, preparation, and compliance.

Automate work paper preparation and eliminate data entry

Trade & Supply

Customs & duties management.

- Customs law compliance & administration

Global trade compliance & management

- Global export compliance & management

- Global trade analysis

- Denied party screening

Product & service classification

- Harmonized Tariff System classification

Supply chain & procurement technology

- Foreign-trade zone (FTZ) management

- Supply chain compliance

Software that keeps supply chain data in one central location. Optimize operations, connect with external partners, create reports and keep inventory accurate.

Automate sales and use tax, GST, and VAT compliance. Consolidate multiple country-specific spreadsheets into a single, customizable solution and improve tax filing and return accuracy.

Risk & Fraud

Risk & compliance management.

- Regulatory compliance management

Fraud prevention, detection & investigations

- Fraud prevention technology

Risk management & investigations

- Investigation technology

- Document retrieval & due diligence services

Search volumes of data with intuitive navigation and simple filtering parameters. Prevent, detect, and investigate crime.

Identify patterns of potentially fraudulent behavior with actionable analytics and protect resources and program integrity.

Analyze data to detect, prevent, and mitigate fraud. Focus investigation resources on the highest risks and protect programs by reducing improper payments.

News & Media

Who we serve.

- Broadcasters

- Governments

- Marketers & Advertisers

- Professionals

- Sports Media

- Corporate Communications

- Health & Pharma

- Machine Learning & AI

Content Types

- All Content Types

- Human Interest

- Business & Finance

- Entertainment & Lifestyle

- Reuters Community

- Reuters Plus - Content Studio

- Advertising Solutions

- Sponsorship

- Verification Services

- Action Images

- Reuters Connect

- World News Express

- Reuters Pictures Platform

- API & Feeds

- Reuters.com Platform

Media Solutions

- User Generated Content

- Reuters Ready

- Ready-to-Publish

- Case studies

- Reuters Partners

- Standards & values

- Leadership team

- Reuters Best

- Webinars & online events

Around the globe, with unmatched speed and scale, Reuters Connect gives you the power to serve your audiences in a whole new way.

Reuters Plus, the commercial content studio at the heart of Reuters, builds campaign content that helps you to connect with your audiences in meaningful and hyper-targeted ways.

Reuters.com provides readers with a rich, immersive multimedia experience when accessing the latest fast-moving global news and in-depth reporting.

- Reuters Media Center

- Jurisdiction

- Practice area

- View all legal

- Organization

- View all tax

Featured Products

- Blacks Law Dictionary

- Thomson Reuters ProView

- Recently updated products

- New products

Shop our latest titles

ProView Quickfinder favorite libraries

- Visit legal store

- Visit tax store

APIs by industry

- Risk & Fraud APIs

- Tax & Accounting APIs

- Trade & Supply APIs

Use case library

- Legal API use cases

- Risk & Fraud API use cases

- Tax & Accounting API use cases

- Trade & Supply API use cases

Related sites

United states support.

- Account help & support

- Communities

- Product help & support

- Product training

International support

- Legal UK, Ireland & Europe support

New releases

- Westlaw Precision

- 1040 Quickfinder Handbook

Join a TR community

- ONESOURCE community login

- Checkpoint community login

- CS community login

- TR Community

Free trials & demos

- Westlaw Edge

- Practical Law

- Checkpoint Edge

- Onvio Firm Management

- Proview eReader

How to do legal research in 3 steps

Knowing where to start a difficult legal research project can be a challenge. But if you already understand the basics of legal research, the process can be significantly easier — not to mention quicker.

Solid research skills are crucial to crafting a winning argument. So, whether you are a law school student or a seasoned attorney with years of experience, knowing how to perform legal research is important — including where to start and the steps to follow.

What is legal research, and where do I start?

Black's Law Dictionary defines legal research as “[t]he finding and assembling of authorities that bear on a question of law." But what does that actually mean? It means that legal research is the process you use to identify and find the laws — including statutes, regulations, and court opinions — that apply to the facts of your case.

In most instances, the purpose of legal research is to find support for a specific legal issue or decision. For example, attorneys must conduct legal research if they need court opinions — that is, case law — to back up a legal argument they are making in a motion or brief filed with the court.

Alternatively, lawyers may need legal research to provide clients with accurate legal guidance . In the case of law students, they often use legal research to complete memos and briefs for class. But these are just a few situations in which legal research is necessary.

Why is legal research hard?

Each step — from defining research questions to synthesizing findings — demands critical thinking and rigorous analysis.

1. Identifying the legal issue is not so straightforward. Legal research involves interpreting many legal precedents and theories to justify your questions. Finding the right issue takes time and patience.

2. There's too much to research. Attorneys now face a great deal of case law and statutory material. The sheer volume forces the researcher to be efficient by following a methodology based on a solid foundation of legal knowledge and principles.

3. The law is a fluid doctrine. It changes with time, and staying updated with the latest legal codes, precedents, and statutes means the most resourceful lawyer needs to assess the relevance and importance of new decisions.

Legal research can pose quite a challenge, but professionals can improve it at every stage of the process .

Step 1: Key questions to ask yourself when starting legal research

Before you begin looking for laws and court opinions, you first need to define the scope of your legal research project. There are several key questions you can use to help do this.

What are the facts?

Always gather the essential facts so you know the “who, what, why, when, where, and how” of your case. Take the time to write everything down, especially since you will likely need to include a statement of facts in an eventual filing or brief anyway. Even if you don't think a fact may be relevant now, write it down because it may be relevant later. These facts will also be helpful when identifying your legal issue.

What is the actual legal issue?

You will never know what to research if you don't know what your legal issue is. Does your client need help collecting money from an insurance company following a car accident involving a negligent driver? How about a criminal case involving excluding evidence found during an alleged illegal stop?

No matter the legal research project, you must identify the relevant legal problem and the outcome or relief sought. This information will guide your research so you can stay focused and on topic.

What is the relevant jurisdiction?

Don't cast your net too wide regarding legal research; you should focus on the relevant jurisdiction. For example, does your case deal with federal or state law? If it is state law, which state? You may find a case in California state court that is precisely on point, but it won't be beneficial if your legal project involves New York law.

Where to start legal research: The library, online, or even AI?

In years past, future attorneys were trained in law school to perform research in the library. But now, you can find almost everything from the library — and more — online. While you can certainly still use the library if you want, you will probably be costing yourself valuable time if you do.

When it comes to online research, some people start with free legal research options , including search engines like Google or Bing. But to ensure your legal research is comprehensive, you will want to use an online research service designed specifically for the law, such as Westlaw . Not only do online solutions like Westlaw have all the legal sources you need, but they also include artificial intelligence research features that help make quick work of your research

Step 2: How to find relevant case law and other primary sources of law

Now that you have gathered the facts and know your legal issue, the next step is knowing what to look for. After all, you will need the law to support your legal argument, whether providing guidance to a client or writing an internal memo, brief, or some other legal document.

But what type of law do you need? The answer: primary sources of law. Some of the more important types of primary law include:

- Case law, which are court opinions or decisions issued by federal or state courts

- Statutes, including legislation passed by both the U.S. Congress and state lawmakers

- Regulations, including those issued by either federal or state agencies

- Constitutions, both federal and state

Searching for primary sources of law

So, if it's primary law you want, it makes sense to begin searching there first, right? Not so fast. While you will need primary sources of law to support your case, in many instances, it is much easier — and a more efficient use of your time — to begin your search with secondary sources such as practice guides, treatises, and legal articles.

Why? Because secondary sources provide a thorough overview of legal topics, meaning you don't have to start your research from scratch. After secondary sources, you can move on to primary sources of law.

For example, while no two legal research projects are the same, the order in which you will want to search different types of sources may look something like this:

- Secondary sources . If you are researching a new legal principle or an unfamiliar area of the law, the best place to start is secondary sources, including law journals, practice guides , legal encyclopedias, and treatises. They are a good jumping-off point for legal research since they've already done the work for you. As an added bonus, they can save you additional time since they often identify and cite important statutes and seminal cases.

- Case law . If you have already found some case law in secondary sources, great, you have something to work with. But if not, don't fret. You can still search for relevant case law in a variety of ways, including running a search in a case law research tool.

Once you find a helpful case, you can use it to find others. For example, in Westlaw, most cases contain headnotes that summarize each of the case's important legal issues. These headnotes are also assigned a Key Number based on the topic associated with that legal issue. So, once you find a good case, you can use the headnotes and Key Numbers within it to quickly find more relevant case law.

- Statutes and regulations . In many instances, secondary sources and case law list the statutes and regulations relevant to your legal issue. But if you haven't found anything yet, you can still search for statutes and regs online like you do with cases.

Once you know which statute or reg is pertinent to your case, pull up the annotated version on Westlaw. Why the annotated version? Because the annotations will include vital information, such as a list of important cases that cite your statute or reg. Sometimes, these cases are even organized by topic — just one more way to find the case law you need to support your legal argument.

Keep in mind, though, that legal research isn't always a linear process. You may start out going from source to source as outlined above and then find yourself needing to go back to secondary sources once you have a better grasp of the legal issue. In other instances, you may even find the answer you are looking for in a source not listed above, like a sample brief filed with the court by another attorney. Ultimately, you need to go where the information takes you.

Step 3: Make sure you are using ‘good’ law

One of the most important steps with every legal research project is to verify that you are using “good" law — meaning a court hasn't invalidated it or struck it down in some way. After all, it probably won't look good to a judge if you cite a case that has been overruled or use a statute deemed unconstitutional. It doesn't necessarily mean you can never cite these sources; you just need to take a closer look before you do.

The simplest way to find out if something is still good law is to use a legal tool known as a citator, which will show you subsequent cases that have cited your source as well as any negative history, including if it has been overruled, reversed, questioned, or merely differentiated.

For instance, if a case, statute, or regulation has any negative history — and therefore may no longer be good law — KeyCite, the citator on Westlaw, will warn you. Specifically, KeyCite will show a flag or icon at the top of the document, along with a little blurb about the negative history. This alert system allows you to quickly know if there may be anything you need to worry about.

Some examples of these flags and icons include:

- A red flag on a case warns you it is no longer good for at least one point of law, meaning it may have been overruled or reversed on appeal.

- A yellow flag on a case warns that it has some negative history but is not expressly overruled or reversed, meaning another court may have criticized it or pointed out the holding was limited to a specific fact pattern.

- A blue-striped flag on a case warns you that it has been appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court or the U.S. Court of Appeals.

- The KeyCite Overruling Risk icon on a case warns you that the case may be implicitly undermined because it relies on another case that has been overruled.

Another bonus of using a citator like KeyCite is that it also provides a list of other cases that merely cite your source — it can lead to additional sources you previously didn't know about.

Perseverance is vital when it comes to legal research

Given that legal research is a complex process, it will likely come as no surprise that this guide cannot provide everything you need to know.

There is a reason why there are entire law school courses and countless books focused solely on legal research methodology. In fact, many attorneys will spend their entire careers honing their research skills — and even then, they may not have perfected the process.

So, if you are just beginning, don't get discouraged if you find legal research difficult — almost everyone does at first. With enough time, patience, and dedication, you can master the art of legal research.

Thomson Reuters originally published this article on November 10, 2020.

Related insights

Westlaw tip of the week: Checking cases with KeyCite

Why legislative history matters when crafting a winning argument

Case law research tools: The most useful free and paid offerings

Request a trial and experience the fastest way to find what you need

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Law and Social Science

Volume 14, 2018, review article, the use of case studies in law and social science research.

- Lisa L. Miller 1

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: Department of Political Science, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901, USA; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 14:381-396 (Volume publication date October 2018) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-120814-121513

- Copyright © 2018 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

This article reviews classic and contemporary case study research in law and social science. Taking as its starting point that legal scholars engaged in case studies generally have a set of questions distinct from those using other research approaches, the essay offers a detailed discussion of three primary contributions of case studies in legal scholarship: theory building, concept formation, and processes/mechanisms. The essay describes the role of case studies in social scientific work and their express value to legal scholars, and offers specific descriptions from classic and contemporary works.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- Armour J , Lele P 2009 . Law, finance, and politics: the case of India. Law Soc. Rev. 43 : 3 491– 526 [Google Scholar]

- Babbie ER 2012 . The Practice of Social Research Belmont, CA: Wadsworth [Google Scholar]

- Barker V 2009 . The Politics of Imprisonment: How the Democratic Process Shapes the Way America Punishes Offenders New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Becker HS 1992 . Cases, causes, conjunctions, stories, and imagery. See Ragin & Becker 1992 205– 16

- Bell J 2002 . Policing Hatred: Law Enforcement, Civil Rights, and Hate Crime New York: N.Y. Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Brady H , Collier D 2010 . Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards New York: Rowman & Littlefield [Google Scholar]

- Brereton D , Casper JD 1981 . Does it pay to plead guilty? Differential sentencing and the functioning of criminal courts. Law Soc. Rev. 16 : 1 45– 70 [Google Scholar]

- Bumiller K 1987 . Victims in the shadow of the law: a critique of the model of legal protection. Signs 12 : 3 421– 39 [Google Scholar]

- Burawoy M , Hendley K 1992 . Between Perestroika and privatisation: divided strategies and political crisis in a Soviet enterprise. Sov. Stud. 44 : 3 371– 402 [Google Scholar]

- Calavita K 1986 . Worker safety, law and society change: the Italian case. Law Soc. Rev. 20 : 2 189– 228 [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M 2011 . Politics, prison and law enforcement: an examination of “law and order” politics in Texas. Law Soc. Rev. 45 : 3 631– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Cheesman N 2011 . How an authoritarian regime in Burma used special courts to defeat judicial independence. Law Soc. Rev. 45 : 4 801– 30 [Google Scholar]

- Cichowski R 2007 . The European Court and Civil Society: Litigation, Mobilization and Governance Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Coleman C , Nee LD , Rubinowitz LS 2005 . Social movements and social change litigation: synergy in the Montgomery bus protest. Law Soc. Inq. 30 : 4 663– 736 [Google Scholar]

- Collier D , Brady H , Seawright J 2010 . Sources of leverage in causal inference: towards an alternative view of methodology. See Brady & Collier 2010 161– 200

- Collier D , Gerring J 2008 . Concepts and Method in Social Science: The Tradition of Giovanni Sartori New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Dudas J 2008 . The Cultivation of Resentment: Treaty Rights and the New Right Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Earl J 2008 . Review: “The Process is the Punishment”: thirty years later. Law Soc. Inq. 33 : 3 735– 78 [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein J , Jacob H 1977 . Felony Justice: An Organizational Analysis of Criminal Courts New York: Little Brown [Google Scholar]

- Elster J 1989 . Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Elster J 2007 . Explaining Social Behavior: More Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Ewick P , Silbey SS 1992 . Conformity, contestation, and resistance: an account of legal consciousness. New Engl. Law Rev. 26 : 3 731– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Ewick P , Silbey SS 1998 . The Common Place of Law: Stories from Everyday Life Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Feeley M 1979 . The Process Is the Punishment: Handling Cases in a Lower District Court New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer A 2012 . Haiti, free soil, and antislavery in the revolutionary Atlantic. Am. Hist. Rev. 17 : 1 40– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Flemming RB , Nardulli PF , Eisenstein J 1993 . The Craft of Justice: Politics and Work in Criminal Court Communities Philadelphia: Univ. Pa. Press [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M 1974 . Why the “haves” come out ahead: speculations on the limits of legal change. Law Soc. Rev. 9 : 95– 160 [Google Scholar]

- George AL , Bennett G 2005 . Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J 2007 . Case Study Research: Principles and Practices New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J 2012 . Mere description. Br. J. Political Sci. 42 : 2 721– 46 [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg T 2003 . Judicial Review in New Democracies: Constitutional Courts in Asian Cases New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Goertz G 2006 . Social Science Concepts: A User's Guide Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Goertz G , Mahoney J 2012 . A Tale of Two Cultures: Qualitative and Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Gómez LE 2016 . Connecting critical race theory with second generation legal consciousness work in Obasogie's Blinded by Sight . Law Soc. Inq . 41 : 4 1069– 77 [Google Scholar]

- Gould JB , Barclay S 2012 . Mind the gap: the place of gap studies in socio-legal scholarship. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 8 : 323– 35 [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse CJ , Yngvesson B , Engle DM 1994 . Law and Community in Three American Towns Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Hedström P , Swedberg R 1996 . Social mechanisms. Acta Sociol 39 : 281– 308 [Google Scholar]

- Hedström P , Ylikoski P 2010 . Causal mechanisms in the social sciences. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 36 : 49– 67 [Google Scholar]

- Hendley K 1993 . The quest for rational labor allocation within Soviet enterprises: internal transfers before and during Perestroika. Beyond Sovietology: Essays in Politics and History S Solomon 125– 58 Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe [Google Scholar]

- Hendley K 2017 . Everyday Law in Russia Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Heumann M 1978 . Plea Bargaining Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Hilbink L 2011 . Judges Beyond Politics in Democracy and Dictatorship New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Hirschl R 2009 . Towards Juristocracy: The Origins and Consequences of the New Constitutionalism Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Holzmeyer C 2009 . Human rights in the era of neoglobalization: the Alien Tort Claims Act and grassroots mobilization in Doe v . Unocal. Law Soc. Rev . 43 : 2 271– 304 [Google Scholar]

- Jacob H 1983 . Trial courts in the United States: the travails of exploration. Law Soc. Rev. 3 : 3 407– 24 [Google Scholar]

- Kagan R 2003 . Adversarial Legalism: The American Way of Law Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Kapiszewski D 2012 . High Courts and Economic Governance in Argentina and Brazil New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Kawar LC 2014 . Commanding Legality: The Juridification of Immigration Policymaking in France Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen RD , Sibbitt EC 2005 . Lex Americana? A response to Levi-Faur. Int. Organ. 59 : 2 463– 72 [Google Scholar]

- King G , Keohane RO , Verba S 1994 . Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre J , Sandvik KB 2015 . Shifting frames, vanishing resources, and dangerous political opportunities: legal mobilization among displaced women in Columbia. Law Soc. Rev. 49 : 1 5– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Faur D 2005 . The political economy of legal globalization: juridification, adversarial legalism and responsive regulation. a comment. Int. Organ. 59 : 2 451– 62 [Google Scholar]

- Lipskey M 1979 . Street-Level Bureaucracy: The Individual in Public Services New York: Russell: Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Massoud MF 2013 . Law's Fragile State: Colonial, Authoritarian and Humanitarian Legacies in Sudan New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Mather L 1979 . Plea Bargaining or Trial: The Process of Criminal-Case Disposition Lexington, MA: Lexington Books [Google Scholar]

- McCann M 1992 . Reform litigation on trial. Law Soc. Inq. 17 : 4 715– 43 [Google Scholar]

- McCann M 1994 . Rights at Work: Pay Equity Reform and the Politics of Legal Mobilization Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Merry SE 1990 . Getting Justice and Getting Even: Legal Consciousness Among Working-Class Americans Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Miller LL 2008 . The Perils of Federalism: Race, Poverty, and the Politics of Crime Control New York: Oxford Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Miller LL , Eisenstein J 2005 . The federal/state criminal prosecution nexus: a case study in cooperation and discretion. Law Soc. Inq. 30 : 2 239– 68 [Google Scholar]

- Milner N 1987 . The right to refuse treatment: four case studies of legal mobilization. Law Soc. Rev. 21 : 3 447– 86 [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa T 2007 . The Struggle for Constitutional Power: Law Politics, and Economic Development in Egypt Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Paris M 2001 . Legal mobilization and the politics of reform: lessons from school finance litigation in Kentucky, 1984–1995. Law Soc. Inq. 26 : 3 631– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Ragin CC , Becker HS 1992 . What Is a Case? Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg G 1991 . The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Change? Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Roussell A 2015 . Policing the anticommunity: race, deterritorialization, in labor market reorganization in South Los Angeles. Law Soc. Rev. 49 : 4 813– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP 1980 . Adjudication and sentencing in a misdemeanor court: The outcome is the punishment. Law Soc. Rev. 15 : 80– 107 [Google Scholar]

- Sarat A 1990 . The law is all over: power, resistance and the legal consciousness of the welfare poor. Yale J. Law Humanit. 2 : 343– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Sartori G 1970 . Concept misinformation in comparative politics. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 64 : 4 1033– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Scheingold SA 1984 . The Politics of Law and Order: Street Crime and Public Policy New York: Longman [Google Scholar]

- Scheingold SA 1991 . The Politics of Street Crime: Criminal Process and Cultural Obsession Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Scheppele KL 2003 . Constitutional negotiations: political contexts of judicial activism in post-Soviet Europe. Int. Sociol. 18 : 1 219– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Scheppele KL 2004 . Constitutional ethnography: an introduction. Law Soc. Rev. 38 : 3 389– 406 [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld H 2010 . Mass incarceration and the paradox of prison conditions litigation. Law Soc. Rev. 44 : 3/4 731– 67 [Google Scholar]

- Seawright J 2016 . Multi-Method Social Science: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Tools Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Seron C 1996 . The Business of Practicing Lives: The Work Lives of Small-Firm and Solo Attorneys Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro M 1983 . Courts: A Comparative Political Analysis Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Silbey SS 1981 . Making sense of the lower courts. Justice Syst. J. 6 : 1 13– 27 [Google Scholar]

- Silbey SS 2005 . After legal consciousness. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 1 : 323– 68 [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein G 2009 . Law's Allure: How Law Shapes, Constrains, Saves, and Kills Politics New York: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Skolnick JH 1967 . Justice Without Trial: Law Enforcement in Democratic Society Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons [Google Scholar]

- Swedlow B 2009 . Reason for hope? The spotted owl injunctions and policy change. Law Soc. Inq. 34 : 4 825– 67 [Google Scholar]

- Tarrow S 2010 . Bridging the quantitative-qualitative divide. See Brady & Collier 2010 101– 10

- Tezcür GM 2009 . Judicial activism in perilous times: the Turkish case. Law Soc. Rev. 43 : 2 305– 36 [Google Scholar]

- Tilly C 2001 . Mechanisms in political processes. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 4 : 21– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Uggen C , Blackstone A 2004 . Sexual harassment as gendered expression of power. Am. Sociol. Rev. 69 : 1 64– 92 [Google Scholar]

- Valverde M 2012 . Everyday Law on the Streets: City Governance in an Age of Diversity Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Yngvesson B 1993 . Virtuous Citizens, Disruptive Subjects: Order and Complaint in a New England Court New York: Routledge [Google Scholar]

Data & Media loading...

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, procedural justice and legal compliance, elaborating the individual difference component in deterrence theory, behavioral ethics: toward a deeper understanding of moral judgment and dishonesty, reproductive justice, the rise of international regime complexity, mass imprisonment and inequality in health and family life, procedural justice and policing: a rush to judgment, immigration law beyond borders: externalizing and internalizing border controls in an era of securitization, law and courts in authoritarian regimes, immigration, crime, and victimization: rhetoric and reality.

- --> Login or Sign Up

The Case Study Teaching Method

It is easy to get confused between the case study method and the case method , particularly as it applies to legal education. The case method in legal education was invented by Christopher Columbus Langdell, Dean of Harvard Law School from 1870 to 1895. Langdell conceived of a way to systematize and simplify legal education by focusing on previous case law that furthered principles or doctrines. To that end, Langdell wrote the first casebook, entitled A Selection of Cases on the Law of Contracts , a collection of settled cases that would illuminate the current state of contract law. Students read the cases and came prepared to analyze them during Socratic question-and-answer sessions in class.

|

|

|

The Harvard Business School case study approach grew out of the Langdellian method. But instead of using established case law, business professors chose real-life examples from the business world to highlight and analyze business principles. HBS-style case studies typically consist of a short narrative (less than 25 pages), told from the point of view of a manager or business leader embroiled in a dilemma. Case studies provide readers with an overview of the main issue; background on the institution, industry, and individuals involved; and the events that led to the problem or decision at hand. Cases are based on interviews or public sources; sometimes, case studies are disguised versions of actual events or composites based on the faculty authors’ experience and knowledge of the subject. Cases are used to illustrate a particular set of learning objectives; as in real life, rarely are there precise answers to the dilemma at hand.

|

|

|

Our suite of free materials offers a great introduction to the case study method. We also offer review copies of our products free of charge to educators and staff at degree-granting institutions.

For more information on the case study teaching method, see:

- Martha Minow and Todd Rakoff: A Case for Another Case Method

- HLS Case Studies Blog: Legal Education’s 9 Big Ideas

- Teaching Units: Problem Solving , Advanced Problem Solving , Skills , Decision Making and Leadership , Professional Development for Law Firms , Professional Development for In-House Counsel

- Educator Community: Tips for Teachers

Watch this informative video about the Problem-Solving Workshop:

<< Previous: About Harvard Law School Case Studies | Next: Downloading Case Studies >>

Legal Research Fundamentals

- Research Strategy Tips

- Secondary Sources

The Different Types of Case Law Research

Popular case law databases, using secondary sources, any good case, from an annotated statute, ai and smart searching.

- Statutory Research

- Legislative History

- Administrative

- People, Firms, Witnesses, and other Analytics

- Transactional

- Non-Legal Resources

- Business Resources

- Foreign and International Law Resources This link opens in a new window

Generally, there are two types of case law research:

- Determining the case law that is binding or persuasive regarding a particular issue. Gathering and analyzing the relevant case law.

- Searching for a specific case that applies the law to a set of facts in a particular way.

These are two slightly different tasks. However, you can use many of the same case law search techniques for both of these types of questions.

This guide outlines several different ways to locate case law. It is up to you to determine which methods are most suitable for your problem.

When selecting a case law database, don't forget to choose the jurisdiction, time period, and level of court that is most appropriate for your purposes.

Note: Listed above are the databases that law students are most likely to use. It's possible that, once you leave law school, you will not have access to the same databases. Resources such as Fastcase or Casetext may be your go-to. For any database, take the time to familiarize yourself with the basic and advanced search functions.

Check out the Secondary Sources tab for information about how to locate a useful secondary source.

Remember: secondary sources take the primary source law and analyze it so that you don't have to. Take advantage of the work the author has already done!

What do we mean by 'any good case'?

A case that addresses the issue you care about. We can use the citing relationships and annotations found in case law databases to connect cases together based on their subject matter. You may find such a case from a secondary source, case law database search, or from a colleague.

How can we use one good case?

1. Court opinions typically cited to other cases to support their legal conclusions. Often these cited cases include important and authoritative decisions on the issue, because such decisions are precedential.

2. Commercial legal research databases, including Lexis, Westlaw, and Bloomberg, supplement cases with headnotes . Headnotes allow you to quickly locate subsequent cases that cite the case you are looking at with respect to the specific language/discussion you care about.

3. Links to topics or Key Numbers. Clicking through to these allows you to locate other cases with headnotes that fall under that topic. Once you select a suitable Key Number, you can also narrow down with keywords. A case may include multiple headnotes that address the same general issue.

4. Subsequent citing cases. By reading cases that have cited to the case you've started with, you can confirm that it remains "good law" and that its legal conclusions remain sound. You can also filter the citing references by jurisdiction, treatment, depth of treatment, date, and keyword, allowing you to focus your attention on the most relevant sub-set of cases.

5. Secondary sources! Useful secondary sources are listed in the Citing References. This can be a quick way to locate a good secondary source.

NOTE: Good cases may come in many forms. For example, a recent lower court decision might lead you to the key case law in that jurisdiction, while a higher court decision from a few years back might be more widely-cited and lead you to a wider range of subsequent interpretive authority (and any key secondary sources).

What is an annotated statute?

An annotated statute is simply a statute enhanced with editorial content. In Lexis and Westlaw, this editorial content provides the following:

Historical Notes about amendments to the statute. These are provided below the statutory text (Lexis) or under the History tab (Westlaw).

Case Notes provided either at the bottom of the page (Lexis) or under the Notes of Decisions tab (Westlaw). These are cases identified by the publisher as especially important or useful for illustrating the case law interpreting the statute. They are organized by issue and include short summaries pertaining to the holding and relevance are provided for each case.

Other Citing References allow you to locate all other material within Lexis and Westlaw that cite to the statute. This includes secondary sources (always useful) and all case law that cites to that specific section. You can narrow down by keywords, jurisdiction, publication status, etc. In Lexis, click the Shepard's link. In Westlaw, click the Citing References tab.

Lexis, Westlaw, and Bloomberg are all actively developing tools to lead you to cases more quickly. These include:

Westlaw's recommendations and WestSearch Plus. These will show up in the "Suggestions" option that appears when you start typing into the search bar.

Lexis Ravel View. When you search the case database in Lexis and click on the Ravel icon, you will see an interactive visualization of the citing relationships between the first 75 cases that appear in your results list, ranked by relevance.

Bloomberg's "Points of Law" feature in the Litigation Intelligence Center also allows users to visualize the citing relationships among cases meeting their search criteria.

- << Previous: Secondary Sources

- Next: Statutory Research >>

- Last Updated: Jun 13, 2024 10:12 AM

- URL: https://law.upenn.libguides.com/researchfundamentals

leiden lawmethods portal

Case study research.

Last update: April 07, 2022

A legal scholar who uses the term ‘case’ will probably first think of a legal case. From a socio-legal perspective, the understanding of this concept is, however, slightly different. Case study research is a methodology that is useful to study ‘how’ or ‘why’ questions in real-life.

Over the last forty years, researchers from sociology, anthropology and various other disciplines have developed the case study research methodology dramatically. This can be confusing for legal researchers. Luckily, both Webley and Argyrou have written an article on case study research specifically for legal researchers. Webley writes, for example, that this methodology allows us to know ‘how laws are understood, and how and why they are applied and misapplied, subverted, complied with or rejected’. Both authors rely upon the realist tradition of case study research as theorised by Yin. Yin defines the scope of a case study as: “An empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”.

Before you start collecting data for your case study, it is important to think about the theory and the concepts that you will want to use, as this will very much determine what your case will be about and will help you in the analysis of your data. You should then decide which methods of data collection and sources you will consult to generate a rich spectrum of data. Observations, legal guidelines, press articles… can be useful. Legal case study researchers usually also rely extensively on interviews. The meaning that interview participants give to their experiences with legal systems can uncover the influence of socio-economic factors on the law, legal processes and legal institutions.

Case studies strive for generalisable theories that go beyond the setting for the specific case that has been studied. The in-depth understanding that we gain from one case, might help to also say something about other cases in other contexts but with similar dynamics at stake. However, you need to be careful to not generalize your findings across populations or universes.

Argyrou, A. (2017) Making the Case for Case Studies in Empirical Legal Research. Utrecht Law Review, Vol.13 (3), pp.95-113

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006.) Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research, Qualitative Inquiry 12( 2), 219-245.

Gerring, J. (2004) What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for? American Political Science Review 98( 2), 341-354.

Simons, H. (2014) Case Study Research: In-Depth Understanding in Context. In P. Leavy (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, Oxford University Press.

Webley, L. (2016) Stumbling Blocks in Empirical Legal Research: Case Study Research. Law and Method, 10.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 26 Mar 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

How Do Great Leaders Overcome Adversity?

In the spring of 2021, Raymond Jefferson (MBA 2000) applied for a job in President Joseph Biden’s administration. Ten years earlier, false allegations were used to force him to resign from his prior US government position as assistant secretary of labor for veterans’ employment and training in the Department of Labor. Two employees had accused him of ethical violations in hiring and procurement decisions, including pressuring subordinates into extending contracts to his alleged personal associates. The Deputy Secretary of Labor gave Jefferson four hours to resign or be terminated. Jefferson filed a federal lawsuit against the US government to clear his name, which he pursued for eight years at the expense of his entire life savings. Why, after such a traumatic and debilitating experience, would Jefferson want to pursue a career in government again? Harvard Business School Senior Lecturer Anthony Mayo explores Jefferson’s personal and professional journey from upstate New York to West Point to the Obama administration, how he faced adversity at several junctures in his life, and how resilience and vulnerability shaped his leadership style in the case, "Raymond Jefferson: Trial by Fire."

- 27 Feb 2024

- Research & Ideas

Why Companies Should Share Their DEI Data (Even When It’s Unflattering)

Companies that make their workforce demographics public earn consumer goodwill, even if the numbers show limited progress on diversity, says research by Ryan Buell, Maya Balakrishnan, and Jimin Nam. How can brands make transparency a differentiator?

- 22 Feb 2024

How to Make AI 'Forget' All the Private Data It Shouldn't Have

When companies use machine learning models, they may run the risk of inadvertently sharing sensitive and private data. Seth Neel explains why it’s important to understand how to wipe AI’s spongelike memory clean.

.jpg)

- 10 Oct 2023

In Empowering Black Voters, Did a Landmark Law Stir White Angst?

The Voting Rights Act dramatically increased Black participation in US elections—until worried white Americans mobilized in response. Research by Marco Tabellini illustrates the power of a political backlash.

- 26 Sep 2023

The PGA Tour and LIV Golf Merger: Competition vs. Cooperation

On June 9, 2022, the first LIV Golf event teed off outside of London. The new tour offered players larger prizes, more flexibility, and ambitions to attract new fans to the sport. Immediately following the official start of that tournament, the PGA Tour announced that all 17 PGA Tour players participating in the LIV Golf event were suspended and ineligible to compete in PGA Tour events. Tensions between the two golf entities continued to rise, as more players “defected” to LIV. Eventually LIV Golf filed an antitrust lawsuit accusing the PGA Tour of anticompetitive practices, and the Department of Justice launched an investigation. Then, in a dramatic turn of events, LIV Golf and the PGA Tour announced that they were merging. Harvard Business School assistant professor Alexander MacKay discusses the competitive, antitrust, and regulatory issues at stake and whether or not the PGA Tour took the right actions in response to LIV Golf’s entry in his case, “LIV Golf.”

- 06 Jun 2023

The Opioid Crisis, CEO Pay, and Shareholder Activism

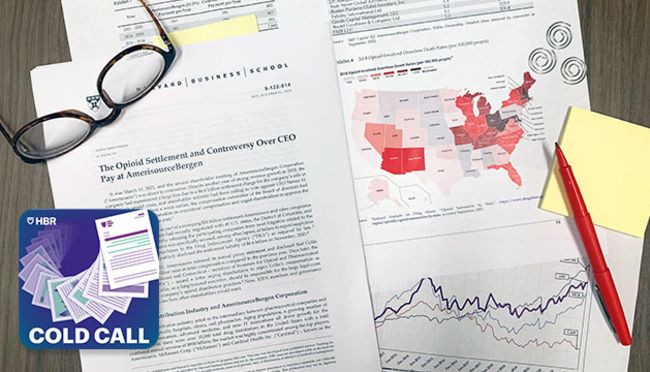

In 2020, AmerisourceBergen Corporation, a Fortune 50 company in the drug distribution industry, agreed to settle thousands of lawsuits filed nationwide against the company for its opioid distribution practices, which critics alleged had contributed to the opioid crisis in the US. The $6.6 billion global settlement caused a net loss larger than the cumulative net income earned during the tenure of the company’s CEO, which began in 2011. In addition, AmerisourceBergen’s legal and financial troubles were accompanied by shareholder demands aimed at driving corporate governance changes in companies in the opioid supply chain. Determined to hold the company’s leadership accountable, the shareholders launched a campaign in early 2021 to reject the pay packages of executives. Should the board reduce the executives’ pay, as of means of improving accountability? Or does punishing the AmerisourceBergen executives for paying the settlement ignore the larger issue of a business’s responsibility to society? Harvard Business School professor Suraj Srinivasan discusses executive compensation and shareholder activism in the context of the US opioid crisis in his case, “The Opioid Settlement and Controversy Over CEO Pay at AmerisourceBergen.”

- 17 Jan 2023

Good Companies Commit Crimes, But Great Leaders Can Prevent Them

It's time for leaders to go beyond "check the box" compliance programs. Through corporate cases involving Walmart, Wells Fargo, and others, Eugene Soltes explores the thorny legal issues executives today must navigate in his book Corporate Criminal Investigations and Prosecutions.

- 29 Nov 2022

How Will Gamers and Investors Respond to Microsoft’s Acquisition of Activision Blizzard?

In January 2022, Microsoft announced its acquisition of the video game company Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion. The deal would make Microsoft the world’s third largest video game company, but it also exposes the company to several risks. First, the all-cash deal would require Microsoft to use a large portion of its cash reserves. Second, the acquisition was announced as Activision Blizzard faced gender pay disparity and sexual harassment allegations. That opened Microsoft up to potential reputational damage, employee turnover, and lost sales. Do the potential benefits of the acquisition outweigh the risks for Microsoft and its shareholders? Harvard Business School associate professor Joseph Pacelli discusses the ongoing controversies around the merger and how gamers and investors have responded in the case, “Call of Fiduciary Duty: Microsoft Acquires Activision Blizzard.”

- 28 Apr 2022

Can You Buy Creativity in the Gig Economy?

It's possible, but creators need more of a stake. A study by Feng Zhu of 10,000 novels in the Chinese e-book market reveals how tying pay to performance can lead to new ideas.

- 04 Jan 2022

- What Do You Think?

Firing McDonald’s Easterbrook: What Could the Board Have Done Differently?

Letting a senior leader go is one of the biggest—and most fraught—decisions for a corporate board. Consider the recent CEO scandal and legal wrangling at McDonald's, says James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 20 Sep 2021

How Much Is Freedom Worth? For Gig Workers, a Lot.

In the booming gig economy, does the ability to set your schedule outweigh having sick leave and overtime? Felix Oberholzer-Gee and Laura Katsnelson turn to DoorDash drivers to find out. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Sep 2021

The Trial of Elizabeth Holmes: Visionary, Criminal, or Both?

Eugene Soltes explains why the fraud case against the Theranos cofounder isn't as simple as it seems, and why a conviction probably wouldn't deter unethical behavior from others. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 23 Aug 2021

Why White-Collar Crime Spiked in America After 9/11

The FBI shifted agents and other budget resources toward fighting terrorism in certain parts of the country, and financial fraud and insider trading ran rampant, according to research by Trung Nguyen. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 23 Feb 2021

Examining Race and Mass Incarceration in the United States

The late 20th century saw dramatic growth in incarceration rates in the United States. Of the more than 2.3 million people in US prisons, jails, and detention centers in 2020, 60 percent were Black or Latinx. Harvard Business School assistant professor Reshmaan Hussam probes the assumptions underlying the current prison system, with its huge racial disparities, and considers what could be done to address the crisis of the American criminal justice system in her case, “Race and Mass Incarceration in the United States.” Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 19 Oct 2020

- Working Paper Summaries

Bankruptcy and the COVID-19 Crisis

Analyzing the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on bankruptcy filing rates in the United States, this study finds that large businesses, small businesses, and consumers experience very different effects of the crisis.

- 12 Aug 2020

Why Investors Often Lose When They Sue Their Financial Adviser

Forty percent of American investors rely on financial advisers, but the COVID-19 market rollercoaster may have highlighted a weakness when disputes arise. The system favors the financial industry, says Mark Egan. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 26 Jun 2020

Weak Credit Covenants

Prior to the 2020 pandemic, the leveraged loan market experienced an unprecedented boom, which came hand in hand with significant changes in contracting terms. This study presents large-sample evidence of what constitutes contractual weakness from the creditors’ perspective.

- 23 Mar 2020

Product Disasters Can Be Fertile Ground for Innovation

Rather than chilling innovation, product accidents may provide companies an unexpected opportunity to develop new technologies desired by consumers, according to Hong Luo and Alberto Galasso. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 01 Nov 2019

Should Non-Compete Clauses Be Abolished?

SUMMING UP: Non-compete clauses need to be rewritten, especially when they are applied to lower-income workers, respond James Heskett's readers. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 28 May 2019

Investor Lawsuits Against Auditors Are Falling, and That's Bad News for Capital Markets

It's becoming more difficult for investors to sue corporate auditors. The result? A weakening of trust in US capital markets, says Suraj Srinivasan. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

Research Guides & Videos

Whether you’re starting a research project or reviewing for an exam, find the resources and explanations you need in our collection of research guides and study aids.

Research Guides by Topic

We’re here to help.

Having trouble finding what you need? We can help with search strategies, resource recommendations, and more.

Ask a Librarian

Study Guides

Audio case files.

Review cases while you work out or commute! AudioCaseFiles provides audio recordings of opinions selected from cases commonly read in first and second year courses. The recordings are produced using professional voice actors and are available for download as mp3 files.

Aspen Learning Library

Access hundreds of your favorite study aids – from Examples & Explanations to Glannon Guides – in ebook, PDF or ePub form. Set up a personalized login to save notes, highlights and bookmarks.

CALI Lessons

CALI, the Center for Computer-Assisted Legal Instruction, provides access to an extensive collection of interactive, computer-based lessons covering a number of subject areas.

Learn the basics and beyond with our in-house instructional videos.

Featured Video Playlists

Related videos grouped together to help you understand a topic quickly.

Legal Research Strategy

Perfect for beginning researchers, this playlist goes through the legal research process step-by-step – 9 videos

Prepare to Practice: Advancing Your Research

This playlist covers advanced legal research concepts and is useful for students starting their summer employment or a new job – 6 videos

Modal Gallery

Gallery block modal gallery.

- Law and Method

- Submission of articles

- Notifications

- Methods courses

- Editorial team

- E-mail alerts

- October, 2016

- Stumbling Blocks in Empirical Legal Research: Case Study Research

- October 2016

- Artikel Stumbling Blocks in Empirical Legal Research: Case Study Research

- Artikel Statistical Analyses of Court Decisions: An Example of Multilevel Models of Sentencing

- Redactioneel Introduction Special Issue Stumbling Blocks in Empirical Legal Research

Citeerwijze van dit artikel: Lisa Webley, ‘Stumbling Blocks in Empirical Legal Research: Case Study Research’, 2016, oktober-december, DOI: 10.5553/REM/.000020

| Artikel | |

| Authors | |

| DOI | |

| |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Dit artikel wordt geciteerd in

- Introduction

Such legal research employs an empirical method to draw inferences from observations of phenomena extrinsic to the researcher. Putting it simply, legal researchers often collect and then analyse material (data) that they have read, heard or watched and subsequently make claims about how what they have learned may apply in similar situations that they have not observed (by inference). 1 x For insight into the extent to which legal researchers undertake empirical research and the lack of clarity around empirical methods in law see Epstein, L. and King, G. (2002) ‘The Rules of Inference’ Vol. 69 No. 1 The University of Chicago Law Review 1-133 at 3-6, Part I. One such form of empirical method is the case study, a methodological term which has been used by some researchers to describe studies that employ a combination of data sources to derive in-depth insight into a particular situation, by others to denote a particular ideological approach to research recognizing that the study is situated within its real-world context. 2 x Yin, R. K. (2014) Case Study Research Design and Methods (5th edn.) Sage Publications, 12-14. It is consequently a flexible definition encompassing approaches to the data and the stance of the researcher, 3 x See Hamel, J. with Dufour, S. and Fortin, D. (1993) Qualitative Research Methods Volume 2 , Sage Publications, ch 1. but its malleability has led some researchers incorrectly to stretch the term to encompass any study that focuses on one or a restricted number of situations. 4 x See Gerring, J. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices , Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007 at 6. For a further discussion see Gerring, J. ‘What is a case study and what is it good for?’ (2004) Vol. 98 No 2 American Political Science Review 341-354. This looseness in definition in a legal context may perhaps be linked to confusion as between teaching and research case studies; some traditions in legal education employ a teaching method known also as ‘case study method’ which operates quite differently from its research counterpart. For a discussion of the differences between teaching and research case studies see Yin, 2014, 20 and for a discussion of teaching case studies see Ellet, W., (2007) The Case Study Handbook: How to Read, Discuss, and Write Persuasively About Cases , Boston MA, Harvard Business Review Press; Garvin, D. A. (2003) ‘Making the Case: Professional Education for the World of Practice.’ (Sept–Oct) Harvard Magazine 56-65. This has resulted in concerns that the definition has been co-opted as a means to explain any small n 5 x ‘n’ (number) is used to denote the number of observations in the study, N is used to describe the total number within the population when n denotes the sample observed. empirical study that has a focus on a particular subject, time-frame or location, and further that this has led to poor quality empirical research in law. 6 x For a discussion of the state of empirical research in law see Epstein and King, 2002. This is perhaps unsurprising, as law programmes tend to be very strong at teaching lawyers how to source, interrogate and then draw valid inferences from legal data sources such as cases and legislation, but less adept in the context of other types of data (for example survey data, interviews, non-legal documents and/or observation). 7 x See Webley, L. (2010) ‘Part III Doing Empirical Legal Studies Research Chapter 38 - Qualitative Approaches to ELS’ in Cane, P. and Kritzer, H. (eds.) Oxford Handbook of Empirical Legal Studies , Oxford, Oxford University Press. Case study method usually involves an array of research methods to generate a spectrum of numerical and non-numerical data that when triangulated provide a means through which to draw robust, reliable, valid inferences about law in the real world. 8 x For a discussion about the differences between numerical (quantitative) and non-numerical (qualitative) data see Webley, id; Epstein and King, 2002, at 2-3; King,G., Keohane, R. O., and Verba, S ., Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research , Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1994 at 6. It is relatively underused in empirical legal research. This article aims to make a contribution to those new to the case study method. It will examine the purpose of and why one may wish to undertake a case study, and work through the key elements of case study method including the main assumptions and theoretical underpinnings of this method. It will then turn to the importance of research design, including the crucial roles of the academic literature review, the research question and the use of rival theories to develop hypotheses in case study method. It will touch upon the relevance of identifying the observable implications of those hypotheses, and thus the selection of data sources and modes of analysis to allow for valid analytical inferences to be drawn in respect of them. In doing so it will consider, in brief, the importance of case study selection and variations like single or multi case approaches. Finally, it will conclude with some thoughts about the strengths and weaknesses associated with undertaking research via a case study method. It will address frequent stumbling blocks encountered by researchers, as well as ways so as to militate against common problems that researchers encounter. The discussion is necessarily cursory given the length of this article, but the footnotes provide much more detailed sources of guidance on each of the points raised here. This article is an introduction to a case study method rather than an analytical work on the method.

- 1. Case Study Method: Purpose of a Case Study, Why Undertake One?

Case study method falls within the social science discipline and as such has scientific underpinnings. The case study examines phenomena in context, where context and findings cannot be separated. Case study design is also sometimes used to investigate how actors consider, interpret and understand phenomena (e.g., law, procedure, policy) and therefore allows the researcher to study perceptions of processes and how they influence behaviour, for example to understand judges’ sentencing choices in a Dutch police court. 9 x Mascini, P., van Oorschot, I., Weenink, D. and Schippers, G., (2016) ‘Understanding judges’ choices of sentence types as interpretative work: An explorative study in a Dutch police court’, (37) (1) Recht der Werkelijkheid 32-49. This may help to understand how laws are understood, and how and why they are applied and misapplied, subverted, complied with or rejected. This can flow back into the legal and policy making processes, court procedure, sentencing, punishment, diversion of offenders etc., and may have a high impact as a result. The conditions precedent for case study method have been succinctly explained by Yin as follows:

‘doing a case study would be the preferred method, compared to the others, in situations when (1) the main research questions are “how” or “why” questions; (2) a researcher has little or no control over behavioural events; and (3) the focus of study is a contemporary (as opposed to entirely historical) phenomenon.’ 10 x Yin, 2014: xxxi and further 16-17.

The key points to note here are that a case study is a real-world in-depth investigation of a current complex phenomenon. The research will take place in situ (rather than in the library or moot court room) where the researcher cannot control the behaviour of research participants.

The purpose of the study is to learn how or why something happens or is the way it is, and this is achieved by collecting and triangulating a range of data sources to test or explore hypotheses. 11 x Triangulation is the term used to explain that a research question is considered from as many different standpoints as possible, using as many different data types as possible to permit a holistic examination of the question to see which explanations, if any, remain consistent across all data sources. It caters for a wide range of modes of enquiry: the investigation may be exploratory (explore why or how something is the way it is), descriptive (describe why or how something is the way it is) or explanatory (determine which of a range of rival hypotheses, theories etc. explain why or how X is the way it is). 12 x Yin, 2014: 5-6. Some categorise case studies as those designed to be theory orientated, and those designed to be practice orientated. 13 x See Dul, J. and Hak, T. (2008) Case Study Methodology in Business Research , Oxford: Elsevier 8-11, 30-59. Thereafter the design scope is very broad; the data collected may be qualitative and/or quantitative, collected via a variety of methods, and the case study may be a single case or be made up of a small number of cases. The breadth of data collected may be illustrated by Latour’s ethnography of the Conseil d’Etat in France, which studied the connections between human and non-human actors to explore their relationship with ‘the legal’ and ‘the Law’ is assembled in that court context. 14 x Latour, B. (2010) The Making of Law: An Ethnography of the Conseil D’Etat , Cambridge: Polity Press. Case study method is a way of thinking about research and a process through which one seeks to produce reliable, fair findings. It can provide deep insight into a particular situation, whether particular in time, in location or in subject-matter. 15 x For a discussion of ethnomethodological aims to study practical life as experienced in context as an end in itself, as experience is subjective and situational, see Small, M.L. ‘‘How many cases do I need?’ On science and the logic of case selection in field-based research’ (2009) Vol. 10 (1) Ethnography 5, 18. It may allow for transferable findings in respect of the theoretical propositions/hypotheses being examined if not to a population as would often be the situation in much quantitative research. 16 x For greater insight on this point see Lipset, S. M., Trow, M. and Coleman, J.S. (1956) Union Democracy: The Internal Politics of the International Typographical Union , New York: New York Free Press at 419-420; Yin, 2014, 21. For a discussion of the problems inherent in aping quantitative terminology in qualitative work see, Small, 2009, 10, and at 19 for further reading on the logic of case study selection and further reading on extended case method. It aims to examine rival hypotheses, propositions, potential explanations previously advanced (exploratory study), or to test findings from a previous case study examining similar phenomena in a new instance (a replication or confirmation study). 17 x Gerring, 2007, 346.

As described so far it is a research method that appears to have a lot in common with experiments and tests of statistical significance. But case study method differs markedly from a big data survey or double-blind experiment in that it seeks explicitly a phenomenon in its natural environment and (in most instances) without means to control for variables, including the behaviour of any participants. 18 x Although note that there are some scholars who believe that case study method can include elements of experimental testing, for example, Gerring, J. and McDermott, R. (2007) ‘An Experimental Template for Case Study Research’ Vol. 51 No. 3 American Journal of Political Science 688-701. One such study in law that has been described by some, if not by the researchers themselves, as a case study did include an experimental design within the battery of methods employed see: Moorhead, R., Sherr, A., Webley, L., Rogers, S., Sherr, L., Paterson, A. & Domberger, S. (2001) Quality and Cost: Final Report on the Contracting of Civil Non-Family Advice and Assistance Pilot (Norwich: The Stationery Office). Experiments aim to control some factors so as to test hypotheses under different conditions, quantitative studies attempt to control for environmental factors through sampling techniques and data collection instrument design so as to minimise their biasing effects, but case study method does not involve control of the environment, or control for the environment, instead it aims to harness context and work within it. It examines in great detail one situation (referred to as a case or unit) or a very small number of situations, to use context as a means to particularise the findings. It also seeks to explain which elements of context may mean that some of the findings are applicable to other situations and if so under what conditions. A case study tells the researcher about the case and the extent to which previous explanations are sustained, in some instances it may also allow the researcher to make claims that some of the findings can be applied to another case or cases too, although this is heavily dependent on the research design and its execution. 19 x Campbell, D.T. Foreword in Yin, 2014 xviii. But it is rarely, if ever, a method that can be used by one to want to make universal claims. A case is not a proxy for a sample of a population in a survey, for example, it is a study of a phenomenon in itself rather than a means through which to view the whole world. Having said that, samples can be used to help select cases in a sound manner. 20 x Seawright, J. and Gerring, J. (2008) ‘Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options’ Vol. 61 No. 2 Political Research Quarterly 294-308.

Case studies are only one of a number of ways to undertake socio-legal or criminological research and it is important to give proper consideration to the full range of research methods prior to making a final decision to adopt a case study method. 21 x Yin, 2014: chapter 1. It may be better to employ a different one: legal history; doctrinal legal study (legal cases, legislation, regulatory documents); a policy study (policy documents, communiqués etc.); a statistical analysis (an analysis of the number of different types of legal cases that go before the courts, their key features and what role these play in chances of success for the plaintiff); a large-scale survey; stand-alone interviews; or an experiment in a simulated setting (asking lawyers to read through some scenarios and explain what advice they would give to a client in those situations). But a case study could employ a number of these methods in combination, so how then does one determine whether case study method is right for one’s study? It will largely depend on the nature of the research question to be answered and one’s appetite for undertaking in-depth research aimed at achieving thick description (detailed description of how or why something is as it is) 22 x For a discussion see: Ryle, G. (1949). The Concept of Mind . London: Hutchinson; Lincoln, Y.S. and Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry . Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; Holloway, I. (1997). Basic Concepts for Qualitative Research . London: Blackwell Science. and/or triangulated findings derived from a range of data sources that develop a new theory or test existing rival theories. It is an intensive study, it requires extremely good planning and design and a robust approach to data analysis too.

- 2. Case Study Method: Research Design